Douglas Goodale, by the age of 32, had eight years of commercial fishing experience behind him when his job literally took his right arm and very nearly his life. Goodale was working by himself on his 22-foot purple lobster boat, “Barney,” about one mile off the coast of southern Maine near Wells Harbor. Hauling up his third set of double traps, his rope went slack in the heavy six-foot seas and snagged on his antiquated drum winch. While reaching for the winch cut-off switch, the right sleeve of Goodale’s loose-fitting oilskin slicker became snagged in the winding rope, pulling it into the winch head. In a moment of agonizing terror, his hand and then his arm were drawn in and crushed in the machine, flipping him over and completely out of his boat.

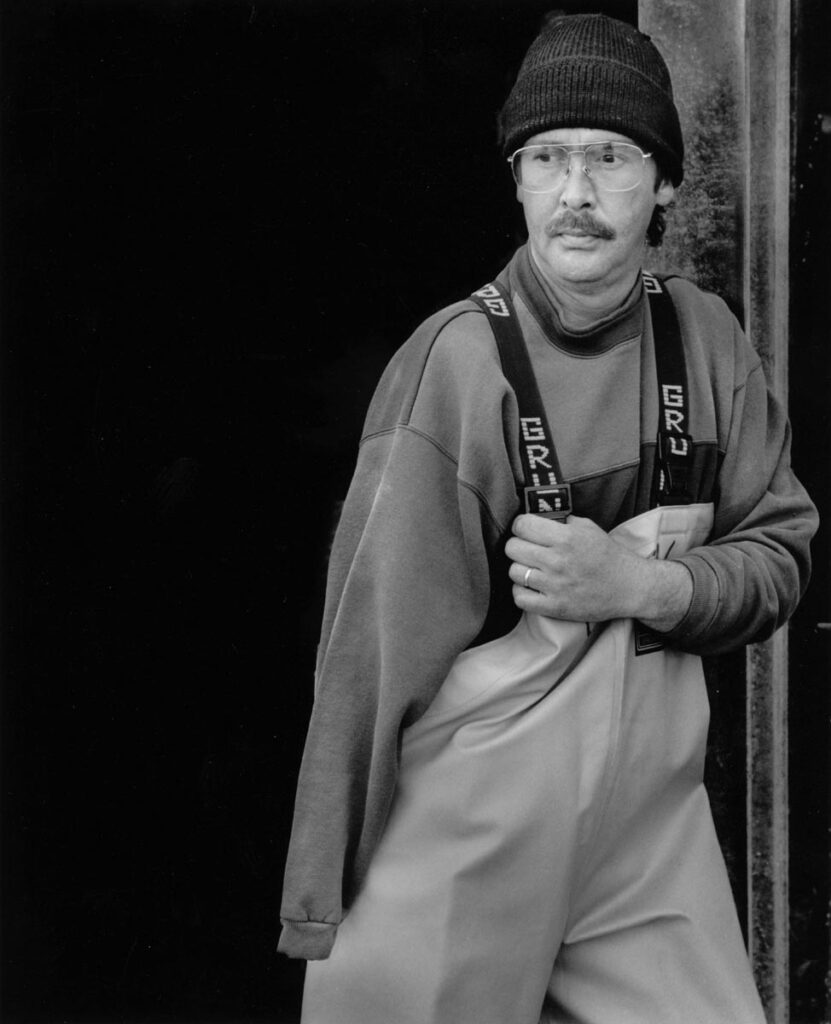

Douglas Goodale, 35, lost his right arm in a winch accident while lobstering off the coast of Maine in 1998. After the accident, Goodale said to his wife, Becky, in the emergency room, “At least I still have my wedding ring.” Strong family and community support have helped Goodale overcome his formidable disability as well as financial barriers and enabled him to return to working on the ocean. “The cost and obstacles have been so great, I wouldn’t have done this unless I loved it,” says Goodale.

With his arm still gripped in the mindless jaws of the winch and his body hanging outside the boat, the near freezing cold North Atlantic Ocean water jolted his senses. The fisherman’s survival instinct left him no choice but to get back aboard. With adrenaline pumping through his body, Goodale used his good arm to pull his water-soaked body up back into the boat. Because of the way his right arm was twisted he had to dislocate the shoulder joint of his injured arm in the process. Staggering in the heaving boat, he broke the kill switch trying to shut down the winch.

“Then I reached for my twine knife by the wheel, cutting through my oil skin to free my arm. I was bleeding quite a bit, but the cold ocean water and the twisting had cinched up the wound.” At full throttle, Goodale piloted his boat through the crashing waves to Wells Harbor. Yelling for help as he approached the wharf, his cry was heard by two fishermen who were preparing herring for lobster trap bait. Goodale, still standing, was now ankle-deep in blood tinged seawater. Twenty minutes later, with help from the fishermen, he was able to get off his boat and lie down on the ambulance stretcher.

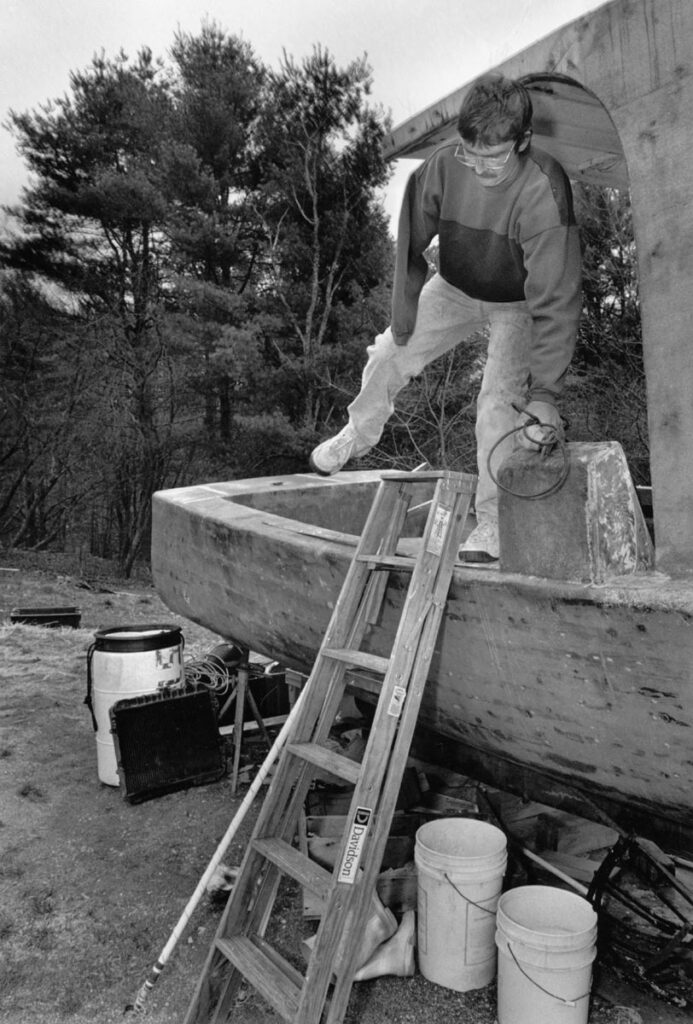

Having only one arm has not kept Goodale from two seasons of lobstering and from completely overhauling his 35’ wooden boat down to the bare planks. Refitting the “Tabby Brat” took Goodale nearly a year and a half of single-handed effort. “For me it was quite a project. Some people wouldn’t have bothered, but I enjoy fishing.”

Becky Goodale, Douglas’ wife, described the scene as she rushed into the emergency room. “There was his arm on one table and him on another. His hand and arm were so crushed and torn that nothing was savable.” Goodale’s first words to his wife were, “At least I still have my wedding ring.”

“I want to be safe and sound now. I’m not going out in a leaky tub anymore. The first time I used this boat, if the battery would have died, the boat would have sunk, it leaked so badly.” The boat is tight as a drum now that Goodale has fiberglassed and gel coated the entire hull. Among many other safety related improvements is the addition of his first radar warning system and a spoked wheel that allows him to maintain course with his knee when his hand is involved in other tasks.

Goodale’s actions in the following few days further demonstrated his strong family and community connections. “After my accident I spent two days and two nights in the hospital then checked myself out because I didn’t want to miss my daughter’s (Tabitha) second birthday. After five days my friends took me out to retrieve my lobster pots.” His wife Becky said she “was kind of amazed he went right back to work.” During the winter, Goodale worked in town at the Highway Department garage painting and at the local transfer station sorting recyclables.

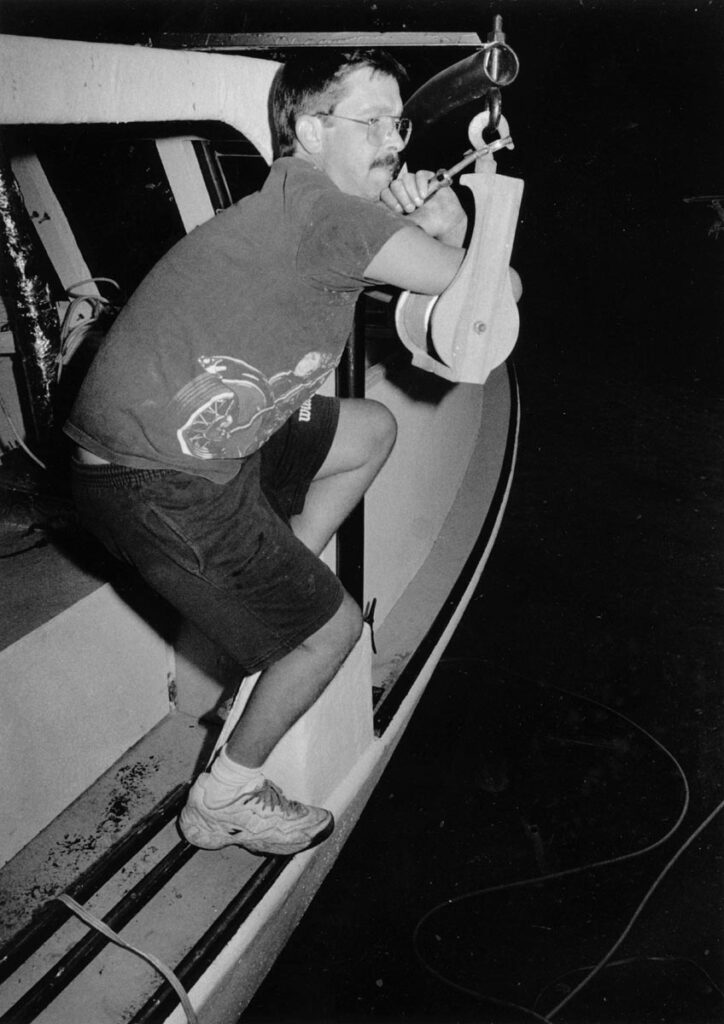

Goodale puts the finishing touches on the “Tabby Brat,” the evening before the launch. He secures the snatch block to the davit arm with a clamp.

Today, Goodale’s frustrations revolve around tasks that require two hands, although that has not kept him from completing a down-to-bare-plank overhaul of the 1955 wooden-hulled boat he purchased after the accident and that he’s named affectionately the “Tabby Brat,” after his youngest daughter. Still, in public he wishes he could “take one of those long balloon’s to make it look like I still have an arm.” He smarts when someone comes up to him and says, “Oh, you’re the guy that lost his arm.”

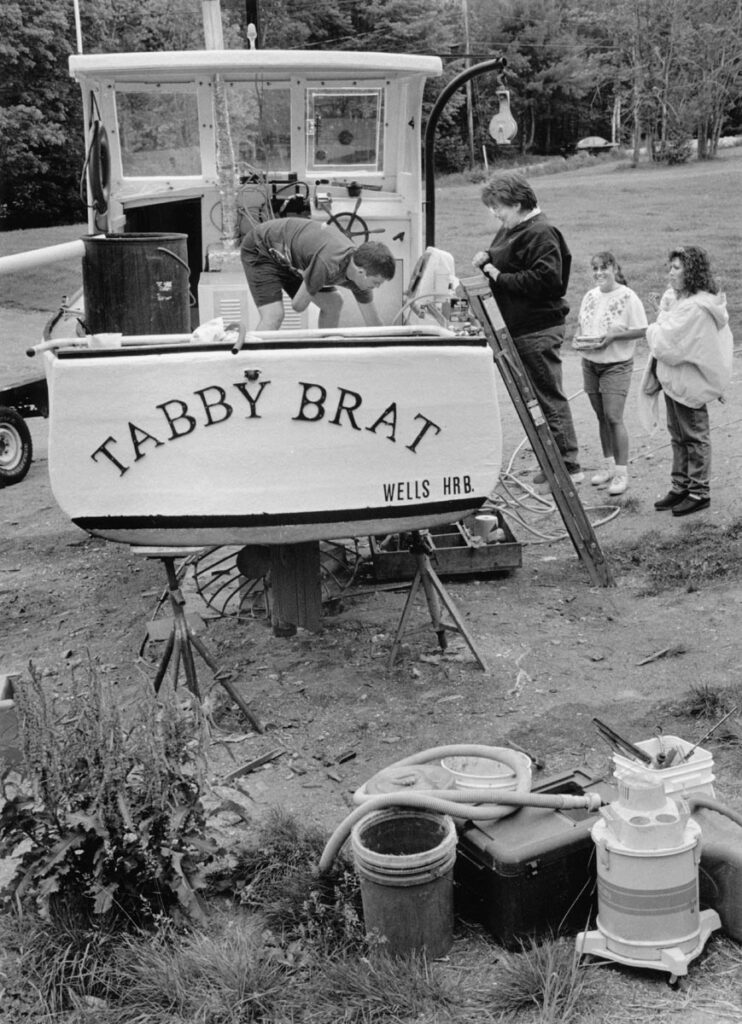

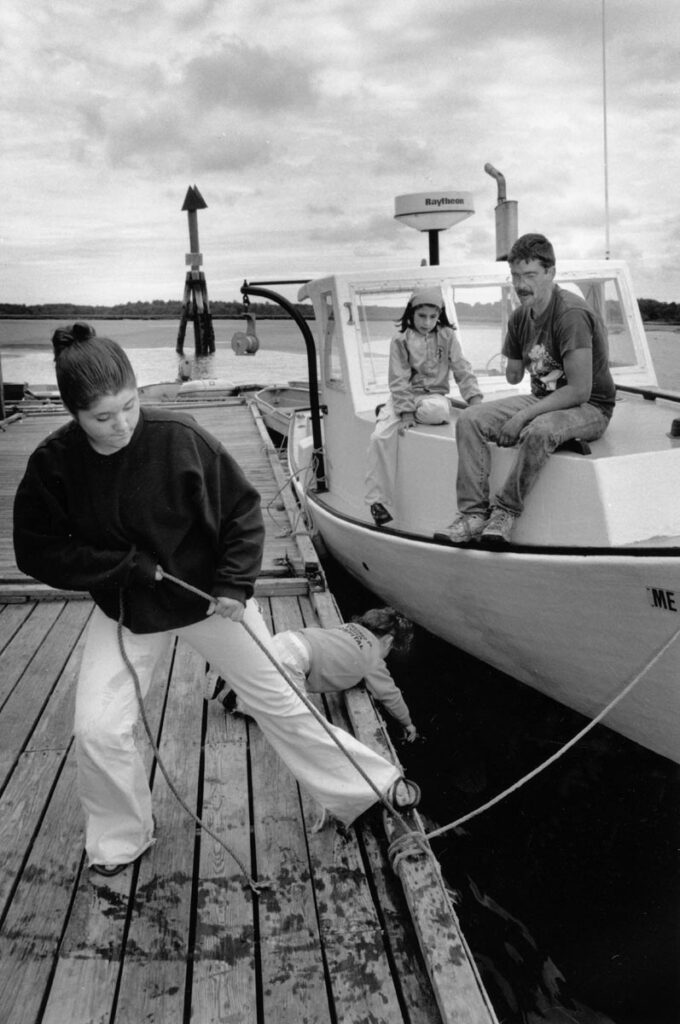

Family members make a final inspection to the completed boat as Goodale makes ready for launch the next morning.

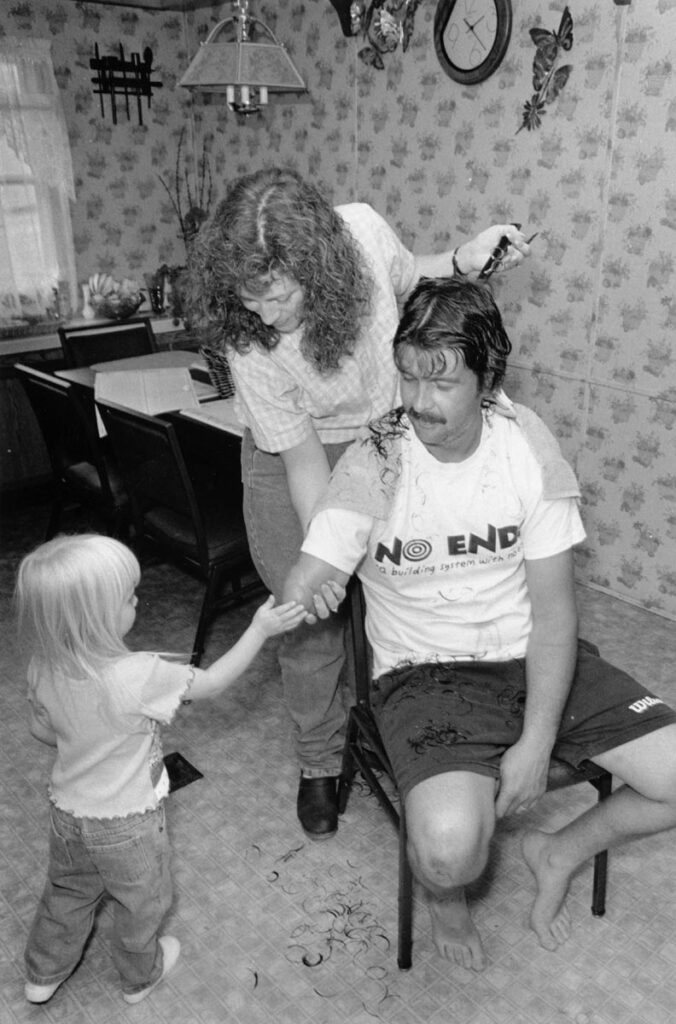

Niece Autumn Atell gives Goodale his “captain’s haircut” as her four-year-old daughter, Maddy, asks Goodale what happened to his arm. Seeking to relax the little girl’s concern, Goodale replied, “Granny caught it in the cookie jar.”

Goodale says, “With two hands I’d have gone right to town and gotten the boat done in two months. But this has been a one handed job. I had to pay for it as I go, taking part-time work, taking breaks to rest my arm. A regular guy could replace the engine starter in twenty minutes. It took me three hours. I began working in March 1999 and finished her in June 2000.”

Along with strengthening the hull and making it water tight, Goodale has incorporated many other safety improvements by equipping the boat with its first radar; changing the round metal steering wheel to one with spokes so he can position it with his knee; securing three well-placed knives, one up front and on the port and starboard sides at the stern to free himself in the event of rope entanglement; building a cage around the prop to avoid submerged trap rope getting caught and stranding the boat without operating power on the open ocean; and most importantly, using a much safer hydro slave winch that makes it almost impossible to succumb to the kind of crushing accident that took his right arm.

As the “Tabby Brat” is moved out of his driveway, Goodale remarked, “This boat is in 200 times better condition than when I first took her out.”

The whole family follows as the “Tabby Brat” is hauled to the harbor. The boat is named after Doug and Becky’s youngest daughter, Tabitha.

On June 14, 2000, Goodale finally launched his overhauled and refitted lobster boat after 18 months of effort. The day before, Goodale reluctantly sold his WWII 8mm Mauser moose hunting rifle to get enough money to replace a faulty alternator. By then he had spent every cent he and the family had on the boat. He said with a shrug, “That rifle was too heavy for me to use now anyway.”

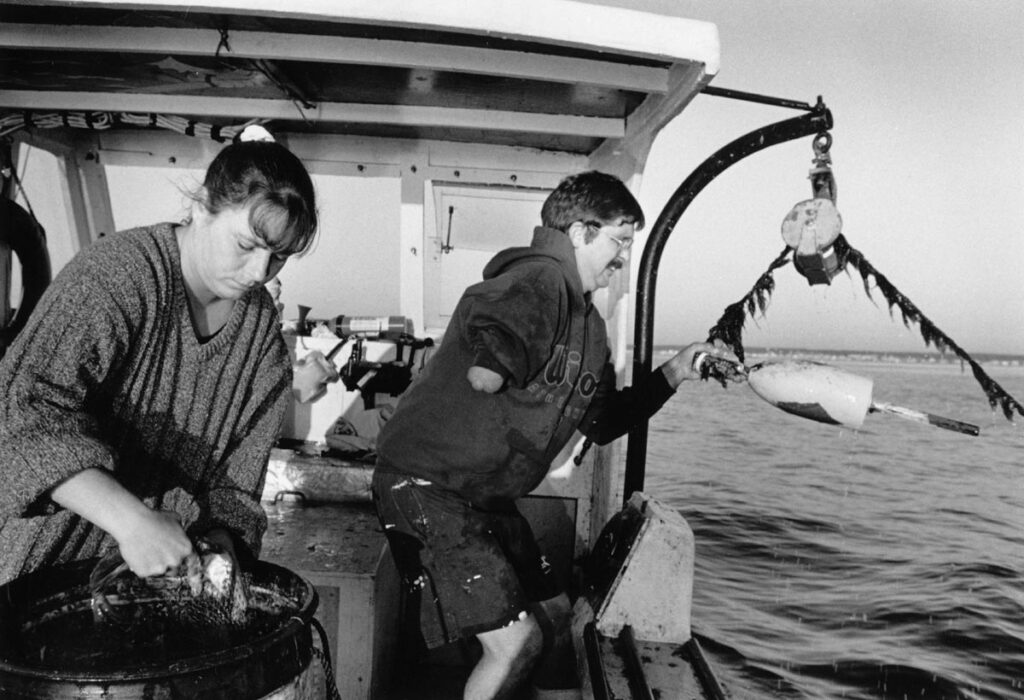

The impact of falling victim to serious injury while working as a commercial fisherman has not been lost on the way Goodale goes about returning to work in what is now the most dangerous job in the United States. “I’ve changed the way I work now. When the lobsters move off shore in the winter, I move home. I call myself a fair weather fisherman. If I have to hold on, I can’t work.” And speaking of his new partner on deck, Becky, he says, “We’ll save a couple of hours out here on the water working together and with two people, it’s definitely safer.” Becky reflects, “With the kids at home with the grandmothers, we work extra safely when we are both out here. They could be orphans if we’re not careful.”

Goodale hauls a lobster pot on board at sunrise on a calm clear morning. “I’ve changed the way I work now. When the lobsters move off shore in the winter, I move home. I call myself a fair weather fisherman. If I have to hold on, I can’t work.”

Becky Goodale works along side her husband readying trap bait. As Douglas snags a trap buoy he remarks, “We’ll save a couple of hours out here on the water working together and with two people it is definitely safer.”

The Goodales spend a rare moment in quiet conversation. Becky reflects, “With the kids at home with the grandmothers, we work extra safely when we are both out here. They could be orphans if we’re not careful.”

Becky Goodale bands the claws of a lobster.

Goodale inspects the notched tail of a female which by law must be thrown back in order to ensure future harvests.

Goodale tosses back a tiny one while smoking an ever-present cigarette, an all too common sight among commercial fishermen. With a pack and a half a day habit, he rolls his own to save money.

Goodale hauls a trap onto the side rail to open it.

The baited trap is returned to the deep. In about four days it will be brought to the surface again.

Goodale attempts to free a lobster trap hung up on the bottom. “Let’s face it, for me it’s a hard occupation without already being injured. These safety rules were made because people are getting killed. The wardens are finding drowning victims, fishermen burnt up, blown up-all kinds of accidents over and over again. These accidents all end up as laws.”

By late morning the catch is counted as the Goodales steam toward the harbor. Goodale offers this assessment of commercial fishing today, “A lot of fishermen are trading their families for only an average income. Swordfishermen, gill netters, shrimpers are gone all the time. And with the danger it takes a lot longer to get to the hospital from way out on the water.”

As Goodale approaches the harbor, Becky catches a catnap. The Goodales began their morning with a 3:30 am alarm set to roust them out of their bed for their day’s work on the ocean.

©2002 Earl Dotter

Earl Dotter’s photojournalism work with New England fishermen is supported by a Josephine Albright Patterson Fellowship from the Alicia Patterson Foundation. The Visiting Scholars Program at the Harvard School of Public Health assisted Dotter in contacting members of the New England commercial fishing community.