“I’m tired,” a depressed-looking, middle-aged woman, pushing a shopping basket loaded with groceries through a Farmer Jack supermarket in a Middle West city, said one day not long ago. “The price of food makes me tired.”

It should. A one-half gallon carton of white milk, 93 cents. A 12-ounce container of frozen orange juice, 83 cents. A 12-ounce package of Peschke’s bacon, $1.28. A pound of Land 0 Lakes butter, $1.55. A one and twelve-hundredths pound package of hamburger, $1.43. A can of Chicken of the Sea tuna fish, $1.44. A two-pound can of Maxwell House Coffee, $5.58.

Food prices have soared in the past years-70 percent in the last ten years, 10.5 percent in 1978, an expected 6 to 11 percent in 1979.

Always trying to put the best face on things, the U.S. Department of Agriculture says that Americans spend little on food, compared to other nations. Moreover, America, the department says, is the best-fed nation in history. According to the department, Americans spend only 17.7 percent of their disposable income on food, behind shelter, on which they spend 29.2 percent, and about what they spend on transportation, 18 percent. Japan spends 32 percent of its consumer income on food, the department says, West Germany 27 percent, France 24 percent. And Americans have a wondrous selection of foods in their supermarkets, row after row of-things-the very symbol of this country, the envy of people around the world. To be an American, surely, is to be fortunate, blessed- as stuffed as the Christmas goose.

Our National Dish

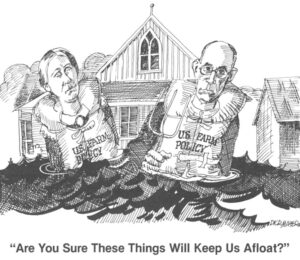

But if we spend so little on food, why is that lady in the Farmer Jack market-and millions like her around the country-so sullen? Why are newspapers running stones on how to make attractive meals from hamburger and macaroni and cheese? Last November, Senator Robert Dole, Republican of Kansas, told the National Grange that America had ended its cheap energy policy but still retained its cheap food policy. If we have a cheap food policy, what will prices look like when the nation adopts an expensive food policy? Will Congress then designate tuna fish casserole as the national dish?

Yet, with food prices rising so dramatically, why are many farmers complaining? Why have several hundred farmers, in a confederation known as the American Agriculture Movement, descended upon Washington like Coxey’s Army, angering Washington commuters with their traffic-snarling tractor cades, camping in front of the Department of Agriculture and the Capitol in campers and pick-up trucks like Gary steelworkers camped around some algae-covered Indiana lake? Why are these weathered men galumphing down the halls of the Rayburn Office Building, making loud noises with their Redwing boots? Why are these men observing, and perhaps sampling, the urban delights along 14th Street and performing circuitous maneuvers with their tractors on Major L’Enfant’s mall, implanting six-inch treads on the lawn forcing the intense joggers to change their stride, perhaps pulling a leg muscle?

If the United States is so well fed, why, in city after city, can you see men and women, just a few cans in their baskets, a package of hamburger, a quart of milk, tuna fish, a loaf of bread, going over every penny before they proceed to the check-out stand? Why are 16 million Americans using food stamps?

Why, at the same time, are six of ten leading causes of death, according to the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs, linked to over consumption of fats, cholesterol, sugar, salt and alcohol? Why are 30 percent of middle-aged men and 40 percent of middle-aged women obese? Why is one-third of the American population overweight to the extent that life may be shortened?

How Poorly We Eat

The answers-they run counter to common assumptions-are that we do not have cheap food nor, in major ways, are we a particularly well-fed nation. The nation’s food system, complex, depending heavily on food technology-a totally Americanized system-is exceedingly costly. Surely, too, it is spurious to compare food costs in the United States, with its vast food-producing lands, to nations like Japan, West Germany and France, which have little farmland. It is, finally, clear that with the growth of food technology, the American diet and meal habits have been altered dramatically. We are eating highly processed- and expensive- foods. Horne cooking in the traditional notion, with roasts, mashed potatoes, salad, perhaps a pie, is, in many ways, obsolete. And almost no one, I suspect, understands how poorly many Americans eat, not only the poor, the aged, lonely old women in walk-up apartments, preparing dinners of instant coffee, cheap hamburger, crackers, but also many working-class and middle-class families, their meals consisting of say, fruit punch, macaroni and cheese, white bread, margarine, gelatin salad, perhaps a vegetable, perhaps not.

Facts About Food

Americans spend a great deal of money-$257.8 billion in 1978, about $1,172 a person, according to the Department of Agriculture-on food and drink, including alcoholic beverages.

Generally, in recent years, about 40 percent of that goes to the American farmer, the department says, with 60 percent, known in department parlance as the marketing bill, going to process the food, package it, advertise it, transport it, and sell it in supermarkets or restaurants.

The marketing bill, the department says, breaks down this way: 45 to 48 percent, $60 billion, for salaries and wages; 12 to 13 percent, $16 billion, for packaging; 7 to 8 percent, $9 billion, for transportation; 7 percent, $9 billion, for profits; 2 to 3 percent, $2.46 billion, for advertising.

What are we spending our money on? How are we eating?

Here are some instructive facts about food in the United States:

Convenience foods-instant foods, frozen foods, prepared mixes and so on- account for almost one-half of the sales of food for use at home, according to the Department of Agriculture.

More than one-third of the money that Americans spend for food is spent on food consumed away from home. This includes college dormitories and hospitals, places where you must eat if that is where you are. But the amount of money spent in restaurants and other eating and drinking places is rising markedly, from 55 percent to 67 percent of the costs for non-home food consumption in the last 25 years. Together, the costs of convenience foods and eating away from home total $184.9 billion in 1978 -more than 80 percent of the money Americans spend on food.

The consumption of a number of basic foods has dropped, while consumption of processed foods has increased dramatically. For example, flour consumption has dropped from 220 pounds per person in 1900 to 115 pounds today. As late as 1940, flour for home use, that is, to be baked into breads, pies and cakes, constituted 50 percent of the flour sold in the United States. Now it constitutes about 11 percent. Most flour today is consumed in processed breads, cakes and pies, and in the buns sold by fast-food restaurants. Consumption of fresh potatoes has dropped nearly 75 percent between 1910 and 1977, even though consumption of potato products, largely frozen french fries, has increased markedly, up 465 percent between 1960 and 1970, for example. Similarly, 40 percent of all beef is now served as ground beef, and this is expected to rise to about 60 percent by the mid1980s. We are, as Secretary of Agriculture Bob Bergland says, close to becoming a hamburger society.

Farmlands Diminishing

Almost no effort is made in the United States to preserve farmlands. Many of the finest agricultural lands are located in or near developed areas. That, after all, is what attracted settlers there in the first place. As these lands are taken by development, other lands must be converted to agriculture, often at great expense in irrigation and fertilizers, thus adding to food costs. Moreover, as lands near cities are taken from farm use, food transportation costs increase, for foods must be transported farther.

The poor spend as much as 40 percent or more of their income on food, according to the Department of Agriculture; the wealthy spend 10 percent. The price of food is not a major concern to many people in this country, including, many of those people who monitor farm and food policies. They can afford the best kinds of food. They talk about inflation, symbolized by rising food costs, as a serious problem. Then it’s off to the Senate dining room or to a fine restaurant for lunch. On a trip to Washington not long ago, I saw a man, somewhat obscured in the darkened cavern of his black limousine, stopped at a fruit stand, as his chauffeur, at the curb, purchased him an apple. Can food costs be a grave matter in Washington?

The United States is enmeshed in a food system that is complex, involves countless people, and is based to a large “tent on technology, both in the fields and at the food manufacturing companies. At the same time, the many people involved in the system must earn a living.

The middleman, the bete noir of farmer and consumer alike, deserves understanding. Perhaps he should hire a public relations agency to hone his image. Not long ago I spent a number of weeks following a steer from farm to market, from the Missouri plains where he was born, through an Illinois farm where he was fattened, at the Illinois stockyard where he was sold, the packing house where he was slaughtered, the store, in New Jersey, where the meat was sold. No one took exorbitant profits.

A Food Revolution?

The upper income, the middle class, some of the working class, are eating well. But many others are not. All kinds of newspapers and magazines, in a trend spurred in the late 1960s, by Clay Felker’s New York magazine, publish stories about what is called gourmet cooking and send reviewers, perhaps the education writer, perhaps someone with some knowledge of food but largely looking for an expense account meal, off to review restaurants. Cookbooks are fast-selling items, and their authors can be seen on television talk shows. This kind of thing is everywhere. Is the chef creative? Is the fish fresh or, sweet God, frozen? What is the consistency of the caramel sauce? Have the wines been cellared correctly? Some people are indeed home with their food machines, blending this, chopping that, working away anxieties, the Joy of Cooking high in the free hand, creating a quiche that is truly provocative. But not much of the United States, truth be told, is undergoing a food revolution.

All of us are spending a great deal for food; some can afford it and don’t realize it; others know the high costs, but can do nothing about them. Many buy down, purchasing cheaper, lower quality foods. Many people in all economic classes are eating diets not particularly nutritious, loaded with sugar and salt. We have many bad dating habits. Yet, I suspect, we eat the way we do because that is the kind of people we are.

The United States has about two million farmers, according to the General Accounting Office. In 1978, America’s farmers earned about $62 billion, according to the Department of Agriculture, the highest income the nation’s farmers have ever received. The previous high was $57.1 billion in 1973, the year of extensive grain sales to foreign nations. But American farm and food policies are replete with paradoxes and masked truths. And this is true of farm income.

It is probably correct, as Wayne D. Rasmussen, the respected historian with the Department of Agriculture, says, that farmers are never happy. And the “search for a fair price,” Don Paarlberg, a well-known economist and former director of agricultural economics for the Department of Agriculture, once said, “has been going on ever since the Middle Ages.” Farmers, an old professor once told him, Paarlberg says, always want 10 percent more than they received, and consumers believe a fair price is 10 percent less than they paid. Still, Paarlberg said, he believed that a fair return to farmers would be “around 40 (percent) or in the low 40s.” Farmers, according to USDA estimates, have, as a whole, earned that return in recent years.

Farming, like food processing and food retailing, like many sectors of the American economy, is highly concentrated, however, and a comparatively small number of farms account for a large share of agriculture sales. According to the GAO, two percent of American farms account for 37 percent of farm sales. The largest 20 percent of farms account for 80 percent of farm sales. Less than one-third of the nations farms, according to the Department of Agriculture, have sales of more than $20,000, the lowest amount of sales a farm can earn, many economists say, and be considered a commercial farm. This means that more than two-thirds of the nation’s farms cannot be considered commercial- a term generally synonymous with success.

Many farmers cannot earn enough money from their farm operations, so they, their wives or children must take jobs in a small town nearby or a larger town a few miles away. In 1978, farmers received $28.3 billion in farm income, the second largest income ever received. But off-farm income totaled as much as $34.4 billion, topping farm income as it has for several years.

The return to farmers varies with the products he raises. It is higher on foods like meat, poultry, and eggs, which receive a minimum of processing, generally standing at 50 to 60 percent. On butter, it is high, sometimes 75 percent. It is low on highly processed foods, generally 15 to 35 percent, for example, on bakery and cereal items, 20 to 30 percent -for fruits and vegetables. On bread it has run as low as 15 percent. As the nation increasingly turns to highly processed foods, which offer better returns to food processing companies and higher costs to the consumer, the farmer’s share of the nations food dollar decreases.

At the same time farmers face soaring production costs, in large part because farming, like other sectors of the food industry, increasingly depends on new technology, new, powerful machines, increasingly expensive fertilizers and other farm chemicals. Farm income rises, but production costs rise, too. The farmer is caught, and often little can be done.

An irony is that, according to virtually all studies, including those of the Department of Agriculture, it is the family sized farm, of, say, 160 acres, the old homestead size, to a few hundred acres, depending on the location and the kind of operation, that produces food most efficiently. B.F. Stanton, an agricultural economist at Cornell University and president of the American Agricultural Economists Association, says that, generally, a farmer with annual gross sales of, say, $100,000, make enough money to live decent lives. But many farmers, like many other Americans, feel the need to expand, and while that can bring prestige and added income, it also can bring headaches and financial problems. Many farmers, including the kind now camped in Washington, showing belligerence, made large investments in land and equipment in the early 1970s, when farm income soared dramatically. Farmers, it is often said, believe bad times will end soon and good times will last forever. Then, when incomes shrank, many farmers faced enormous difficulties.

Consumerism

Many food processing companies are gigantic firms, with sales of several billion dollars a year, and with products in every category, a coffee, say, perhaps an orange juice, numbers of processed foods, a drink, a pet food, frozen pizza, an ice cream, a franchised restaurant arm. For example, General Mills sells a long list of cereals, including Wheaties and Cheerios, the Betty Crocker cake mixes, Saluto pizza, and owns Red Lobster Inns. General Foods markets Maxwell House coffee, Post cereals, Kool-Aid, Jell-O, Tang and the Burger Chef restaurants. Pillsbury also owns Green Giant foods, Totino’s frozen pizza and Burger King restaurants. Beatrice Foods markets Tropicana orange and other juices, and the Meadow Gold, Viva, LaChoy and Eckrich brands. Ralston Purina sell Chicken of the Sea tuna, Chex cereals, a long list of pet food, including Cat Chow and Dog Chow, and Jack-in-the-Box franchise food.

With government regulation of cigarette advertising, a number of tobacco companies have entered the food and drink business, Philip Morris with 7-Up, R.J. Reynolds with Hawaiian Punch and Chun King oriental foods. Farm cooperatives, founded decades ago to assist farmers in obtaining better prices for their crops, have become as large as, or larger, than many private food companies. Milk co-operatives, for example, possess enormous market power. And Sunkist, a cooperative, is the nation’s largest exporter of citrus fruits, shipping 80 percent of the nation’s fresh lemons and half of its fresh oranges. It is estimated that 80 percent of the irrigated citrus-producing lands in California and Arizona are controlled by Sunkist members.

In approaching the food market, says. Fortune, the business magazine, companies attempt to identify “consumer hot buttons” -highly processed items, generally, like General Mills’ Breakfast Squares, or General Foods’ Stove Top prepared stuffing, that seem to pique a particular consumer interest.

Mergers and Acquisitions

The concern of a number of observers of the food industry is over the enormous power possessed by the large firms. Mergers and acquisitions are common. The number of food companies, complains Carol Tucker Foreman, Assistant Secretary of Agriculture, has declined from 44,000 in 1947 to 22,000 in 1972. This trend is continuing. J.M. Connor, in a forthcoming study, says that 200 corporations control 63.5 percent of food and tobacco processing sales. Along with a fellow researcher, Russell C. Parker, Connor estimates monopoly overcharges in the food manufacturing industries at $10 billion, or about 6 percent of food sales, in 1975. For farmers, as concentration increases the number of potential buyers for their products is restricted, and therefore, many charge, their chances of getting a good price are lowered. Both livestock production and slaughtering operations, for example, are highly concentrated. Nearly four- fifths of the vegetables processed in the United States, according to one estimate, are grown by “contract farmers”- farmers who, before the season even starts, have agreed to a set price from a food processor.

Willard F. Mueller, of the University of Wisconsin, an expert on anti-trust matters, says that the prime factor in increasing concentration in consumer product industries, such as food processing, is television advertising. A significant share of television revenues come from the food industry. Mueller says large conglomerate firms engage in “predatory marketing strategies,” and he cites as an example Proctor & Gamble’s acquisition of Folger Coffee in the 1960s and P & G’s use of what Mueller calls willingness to absorb large losses, price discounts, heavy TV advertising and couponing to increase Folger’s share of the market. This, Mueller says, injured many single-line coffee companies. Mueller also cites Philip Morris’ acquisition of the Miller Brewing Company. Philip Morris, he said, engaged in massive advertising and brewery plant expansion to increase Miller’s sales, moving Miller from eighth to second place in the brewery industry in six years. The development helped increase concentration in the beer industry, Mueller says, with the market share of the five largest companies rising from 49 to 73 percent between 1970 and 1978.

A Wealth of Choices

An American supermarket today sells about 11,000 items. In the late 1920s, when supermarkets first were coming on the scene, the typical market sold less than 900 items. Much of the increase has come in things other than food; supermarkets today stock cleaning supplies, paper products, engine oil, shoes, underwear, magazines-items which are not reflected in USDA grocery figures. The item that consumes the most shelf space in a supermarket, for example, is dog food, which accounts for about $3 billion a year, or 5 percent, of supermarket sales. People emerge from a supermarket complaining of high food costs, when their bags may contain a toilet brush, Kleenex, a pair of sneakers, bird seed, sanitary napkins, a garden hose.

Complaints about the lack of profits are a major concern in the food retailing industry, as it is in food manufacturing and farming. Supermarkets like to measure profits as a percent of sales, and say that they are fortunate if profits average one percent of sales. In recent months, Food Fair, Inc., one of the nation’s largest food chains, with sales of $2.5 billion, filed for protection under federal bankruptcy laws, as did Allied Supermarkets, another major chain. A & P, the once-venerable firm, has seen its sales plummet, and, years ago, it lost its number one ranking, which it had held for many years, to Safeway.

Yet, when profits are measured as return on equity, the picture immediately brightens. Forbes praises companies like Albertson’s, Supermarkets General and Safeway Stores, which, the publication says, are well managed and which returned 20.1 percent on equity in 1978. The 13 top national supermarket operations returned 14.3 percent on equity in 1978, for example. Industry-wide, according to Forbes, regional and national chains returned 12.5 percent on equity in 1978, 13.8 percent over the last five years.

As with farming and food processing, food retailing is highly concentrated, and the trend increases each year. An authoritative study of the food retailing industry by the Joint Economic Committee of the U.S. Congress and University of Wisconsin economists shows that the 20 largest chain operations increased their share of food sales from 26.9 percent to 37 percent between 1948 and 1975. Large supermarket chains, those with 11 or more stores, the report says, account for nearly 57 percent of all grocery sales and 70 percent of supermarket sales. Between 1954 and 1972, the report says, the number of metropolitan areas in the country in which food sales are highly concentrated-in which four chains control at least 60 percent of the sales-has increased from 5 percent to 28 percent. Bruce W. Marion, a University of Wisconsin agricultural economist involved in the study, says that concentration added $662 million to the nation’s grocery bill in 1974-and he says that his estimate is conservative.

“Supermarkets are full of profitable fun foods,” reads an advertisement in Progressive Grocer, the trade magazine of the retail food industry. And that, in large part, symbolizes the American food industry.

“What Sells”

In farming, says James Schindler, an agriculture historian and editor of Agricultural History magazine, the trend seems to be “what sells”-devices and techniques that will appeal to expansion minded farmers, high-powered tractors, irrigation machines, fertilizers. This trend is true in food, too. Here is a statement by the research vice president of Libby, McNeil & Libby in the magazine for the Institute of Food Technologists on the “corporate view of new product development”: “…(T)oday’s consumers really don’t need anything in the way of new products, but they are constantly searching for something just a little bit better or different…If a marketing man looks at (the) product spectrum and asks if there is any way to add another kind of orange juice product…the immediate temptation is to ask, ‘Who needs it?’” Yet, he said, a company “could come along with an orange juice product to which additional color or sweetness has been added, or to which an important nutritional component has been added, and do well with it in the marketplace.”

Meantime, while we complain of inflation, led by food prices, we now have many cushions that make inflation, if not welcome, at least acceptable: tens of thousands of families now have second incomes, and many wage earners have automatic cost of living allowances that their unions and companies have negotiated, meaning that inflation can be made up in the workers’ paychecks.

Moreover, as many farmers demonstrate, the drive to expand, to dominate, is an individual as well as a corporate trait. While studies are done on the subjects of concentration in farming, in food processing, in food retailing, little ever happens.

And no one can suggest that Americans do not enjoy their comforts. While it may be true that we should be home baking breads, that we should be tending our vegetable and herb gardens, that we should eat oranges, not potato chips, that is what we often do.

©1979 William Serrin

WILLIAM SERRIN is spending his Fellowship year reporting on farmers, food and farming