MONTAGUE, Mich.–The town of Montague, Michigan, sits up against the rolling bluffs of White Lake, hundreds of miles from the industrial centers of Detroit and Chicago. Every springtime, sap from the sugar maples runs like rainshowers and the lake is fat with perch and bass. In the springtime of 1951, however, there were also no jobs. “We were a community down at the heels,” recalls 79-year-old Wendell Lipka, who lives with his wife of 55 years in a house on the ravine over Little Buttermilk Creek.

So it was, in 1951, that the town of Montague mortgaged its best asset-the clear wilderness lake-for the promise of 125 good-paying jobs and an $11 million tax base. In time, the lake became polluted, the groundwater was destroyed, the town split apart, and a chemical company had to dig a hole as wide as 13 football fields to accommodate the poisonous wastes those 125 jobs had created.

The spirit of expansionism has been as much a part of Montague as any other American town during the past century and White Lake had the misfortune of always having something that somebody wanted. The Ottawa Indians took fish from it. The loggers who founded Montague at the intersection of a river and a lake took water from it to power their saw mills. Sam McConnell, Montague’s first industrialist, built his Eagle Tanning Works on the lake’s eastern shore. The tannery was enough to keep the town alive during the depression but later, during the post-war boom years, the people of Montague became convinced that more industry was their ticket to a better life.

In the winter of 1951, a firm named Hooker Electrochemical Company was scouting Michigan for a site on which to build a chlor-alkali plant. Hooker was based in Niagara, New York, where it had been using an old canal bed for disposal of industrial wastes since the late 1940s. Love Canal was the name of the dump and it would become notorious years later when the buried wastes threatened a nearby neighborhood.

The people of Montague worked feverishly to induce Hooker to their town. A petition was signed by 96 percent of the local residents in support of the company’s plans to build its plant on a ridge bordering White Lake. Hooker needed the vast underground reserves of salt there to make chlorine and caustic soda and the lake water was essential to cool its industrial processes.

In the winter of 1951, White Lake was pristine. The Michigan Department of Natural Resources conducted a biological survey of the four-mile long lake the following year and reported that its benthos, or bottom-dwelling organisms, were those of a naturally eutrophic or nutrient-rich lake. The inhabitants of a healthy aquatic environment-clams, worms and midges-were well represented. The lake suffered only minor irritations from the refuse of the local wastewater treatment plant and the old tannery, which was still in business up at the north end.

The Dying Lake

Hooker bought 880 acres of land about a quarter mile north of the lake, ran its coolant discharge pipes from the plant down into the lake’s middle basin, and went to work. No one paid much attention to what was coming out of the pipes. Pretty soon, the midge larvae started to disappear from the lake, the fingernail clams died, and the pollution-tolerant worms slowly spread across the lake floor.

And the seeds of the conflict that would scar Montague for the next 30 years began to be sown. It was a war that pitted the environmentalists against the jobs in the age-old rivalry of industry versus the land.

The environmentalists fought what they considered to be the duplicity of the company, the failure of the state regulatory agencies to protect the land, and the avarice of the town politicians and businessmen. The other side argued that Hooker-with a $500,000 annual payroll in the early 1950s in a town of less than 3,000 residents-was a good provider. They argued, too, that Hooker was a good neighbor, victimized by the uncertainty of the times. Most people still thought the earth was a giant sponge, soaking up all the pollutants it was fed. The dissenting voices of scientists and hydrogeologists, raised in warning, were then small and lost in the national cacophony of grinding pistons and assembly lines.

“Hooker had been welcomed into the community because, as individuals, they were well-rounded, welleducated, wellspoken people and nobody at that time had any idea what the attitude of industry was toward our natural environment,” recalls A. Winton Dahlstrom, a local attorney. “They said they were dumping nothing but cooling water back in the lake. Yeah, and every drunk has two beers. Well, everybody knows that every drunk has more than two beers and every industry puts every god damned thing in the factory in the cooling water. And that’s in fact what happened.”

In the 1950s, Michigan’s Water Resources Commission was chiefly responsible for monitoring industrial discharges and enforcing the few laws against pollution that existed. The commission was formed in response to the state’s Water Pollution Control Act of 1929, a broad and weakly-enforced law which basically forbade the discharge of harmful things to surface and groundwater. During the past 30 years, the Water Resources Commission and its sister agency, the Department of Natural Resources, have been buffeted by the demands of industry and the weight of their own internal politics. The agencies acted more as consultants than cops and, in the end, the regulators were regulated by industry itself. There is no more flagrant example of the failure of these regulatory agencies than the case of Hooker.

The Water Resources Commission granted Hooker its original waste disposal permit in December of 1952. The decision was heavily supported by the supervisory boards of Montague and Whitehall, its twin city across the lake, despite the faint protests of a local group which raised questions about the storage of the waste on company property and possible contamination of the lake and groundwater. In a moment of high drama at a public hearing on the permit, a Hooker official held up a glass of water containing what he said were all the ingredients that would be dumped into the lake. “Drink it,” he urged the crowd. (There is no record to show if anyone accepted the challenge.)

That same year, the company commissioned an independent geological survey of the brine and water supply for its new plant. The survey reported that the top soils and gravels underneath the plant were “highly permeable” and warned that “with the adjacent lake, and with nearby domestic water supplies, we feel that provisions for any chemical waste … should be disposed of under a procedure that will leave the company free of any possible criticism.”

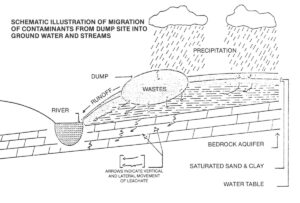

Hooker had built its plant on a bed of fine, porous sand 80 feet thick which contained the principle groundwater stream that supplied the major portion of the local population with drinking water, through private wells and public supply wells. The groundwater roughly followed the lay of the land, sloping down from the Hooker plant and into White Lake, which eventually discharged into Lake Michigan through a slim channel three miles to the east.

During the next three years, the groundwater underneath the plant became contaminated with sodium chloride, table salt. Hooker was storing its salt-laden brine wastes in sludge pits, which periodically overflowed onto the ground. Another survey commissioned by the company in 1956 could not have made the problem clearer. Any soluble contaminant placed on the surface, the report said, “will soon make its way downward and affect the quality of the groundwater.”

Even though Hooker should have been aware by now that something was seriously wrong with the methods used to dispose of its relatively innocuous brine wastes, the company surged ahead in 1956 with plans to begin production of an organic chemical called hexachlorocyclopentadiene, or C56.

Chemical as King

C56 was the raw ingredient of a group of pesticides that gained wide acceptance in the early 1950s. The post-war years had brought a technological revolution in the field of synthetic chemicals used as components of pesticides, herbicides, insecticides, and as additives, to fire retardants and other industrial products. The main selling point of the chlorinated hydrocarbons, a group to which DDT and the C56-based pesticides both belong, was their extreme persistence and effectiveness against a broad spectrum of insects. Two of the most popular C56-based pesticides were Kepone, which was used to kill cockroaches, and Mirex, which the U.S. Department of Agriculture recommended as the most effective opponent of the Southern fire ants. C56 in the vapor form was particularly brutal. The U.S. Army had rejected its use as a nerve gas in World War II on grounds that it was too dangerous to be used as a defensive weapon.

This, however, was the era of chemical as king. Rachel Carson was years away from writing her devastating assessment of the manner in which pesticides damaged the environment. The toxic effects of the chlorinated hydrocarbons were barely suspected and the analytical tools to detect the presence of these chemicals in the environment had not yet been fully developed.

Unburdened by strong evidence about the danger of its waste and unfettered with criticism from the state regulatory agencies, Hooker started up its C56 production plant in 1956. The company told the Water Resources Commission that the maximum toxic effects of this process would be minimal levels of several chemical byproducts which could probably be treated in an oil-type residue separator before being discharged in the effluent to the lake. The spirit of cooperation between the company and the commission staff was so cordial that the Hooker plant manager dropped a friendly note to the commission’s district engineer, complimenting him on how pleasant their meeting had been and reminding Hooker’s man that he had agreed to give a talk on water pollution to the local Rotary Club.

The most critical and mysterious failure of the state regulatory agencies occurred shortly after Hooker began making C56. The state asked the company to supply it with more complete information about the toxicity of the five chemicals discharged in the C56 process. Hooker claims that it supplied the information in a letter. The state says it never got the letter.

A search through 30 years of Department of Natural Resources files shows a gap from the time the state asked Hooker for more information to the time the company was issued a new waste disposal permit later that year.

“The question I have,” says Dr. James Truchan of the DNR’s environmental enforcement division, “is how did this happen? I looked through the files myself and there was silence, no reply back from the company. Yet the permit was issued, without those questions being answered, with the company basically being given a pass to do anything they wanted with those materials.”

“This is where you get speculation,” he added, “that someone went over somebody’s head, or somebody was paying off the department, or somebody in the department just screwed up and forgot about it.”

Split Drums Dump

During the next two decades, the Montague plant produced about 25,000 tons of C56 a year. Yet, the regulatory agencies did not ask where the residues from those 25,000 tons were going. In fact, Hooker employees were quietly piling up 55-gallon drums of C56 residues in a wooded area some distance north of the plant building. The dumping began in 1957 and ended in 1972, when the wastes began to be trucked off the site to other locations in the state. In its lawsuit filed against Hooker many years later, the state described how the drum tops were split open with an axe and then pushed off trucks onto the ground, where they began leaking into the soil. Eventually, some 20,000 barrels of C56 waste were strewn across the dumping ground, where they destroyed 2 billion gallons of groundwater, critically injured White Lake, and threatened the backyard drinking wells of nearby homeowners.

“I don’t believe people realized that when it rained, water was going to run over this material and it was going to leach out,” says W. Ken Hall, Hooker’s current Montague plant manager. “This was a tarry substance and they took fly ash and covered up the drums with it. In their minds, if there was any possibility of any kind of leak, it would be absorbed by the fly ash.”

Hooker president Donald Baeder, who was not with the company then, speculates that the barrels were stacked behind the plant as “kind of a holding action because they really didn’t know quite what to do with those materials.” Baeder thinks the placement of the barrels on top of the ground may actually have been better than if they had buried them in a landfill because of the porosity of the soil.

Although Baeder is critical of the disposal methods used at Montague, he tempers his critique with the caveat that you can’t judge the past by today’s standards. The president also insists that the methods were not employed “in secret.” He visited the Montague plant several years ago to find out if the staff had tried to cover up the barrel dumping operation. “I literally told them, ‘Today, you can tell me anything. There will be no reprimands. I want the truth,”’ Baeder recalls. “And there was no indication from any of the employees out there that they were trying to hide something from the state.”

Yet, in a 1955 memo, another Hooker executive wrote that disposal of wastes at the Montague plant “was a major problem due to local and state ordinances.” While the contamination of ground or surface water was outlawed, the landfilling of industrial wastes on company property was not illegal, and in fact was quite common at the time. So the company turned to land disposal and the storage of waste sludges in lagoons, pits, and on the ground itself.

For a brief time, Hooker had tried a high-temperature incinerator to dispose of the Montague wastes, but it apparently did not work. The company had conducted extensive research on the incineration process during the late 1950s because it had realized earlier in the decade that the proper burial of its chlorinated wastes would be costly, according to a 1966 speech given by Hooker executive Jerome Wilkenfeld to the Montague Foreman’s Association. Wilkenfeld ended his speech with the reminder that it was the responsibility of everyone not to pollute.

‘I think past management really cared within the limits of what they knew,” added Baeder. “I don’t think they were out to foul their nests for profit at all. In hindsight, we probably put too much emphasis on operations and not enough on the environment, but it was probably universal throughout the industry at the time.”

“You can’t tell me,” counters Stewart Freeman, the assistant state attorney general who drafted the Michigan lawsuit agairist Hooker, “that they didn’t know that C56 was harmful. Hooker would have you believe that no one knew anything until magically one day Rachel Carson wrote a book and got everyone upset. That’s just not true.

Napoleon Knew Better

“My predecessors in Michigan were prosecuting a hell of a lot of environmental cases in the 1800s. Even Napoleon had enough sense to locate his troop latrines downstream of waters used for coffee and soaping. And engineers back in the 1920s knew that contamination of surface spreads through groundwater.

“There were very few people in Michigan in the 1950s -chemical company executives and ordinary people alike- who would have disposed of their garbage in their drinking wells.”

Hooker was able to get away with lax disposal methods, however, because the state looked the other way. “People just plain and simply let problems generate and fester and never told anyone about them,” says John Shauver of the DNR’s environmental enforcement staff. “Everybody in the DNR structure had one piece of business and if it wasn’t their business, they didn’t ask about it. No one ever went out Hooker’s back door to look for the barrels.”

The people living near Hooker’s back door didn’t have to look. Chemical fumes from the plant had always bothered the residents nearby on Old Channel Trail, but no one knew quite what to do. In the early 1970s, Marion Dawson wrote the state’s Air Pollution Control Commission about the strange fumes wafting from the Hooker plant. The odor was odd, like a mixture of laundry bleach and geraniums. Dawson was 31-years-old then, a delicate-looking blonde with a schoolteacher husband, an infant son, and a master’s degree in biology. She surveyed residents within a two-mile radius of the plant and they told her the strongest fumes occurred between midnight and 8 a.m. People had difficulty breathing, their eyes and noses itched and watered. Sometimes children had to be brought in from playing outside when the fumes were strong. Six people reported the death of trees in their yards. Hooker had replaced two of them.

It was the odor of C56, later found in concentrations of 17 parts per billion in the air near the barrel dump. By contrast, 10 parts per billion is the established threshold limit for human exposure to C56. Marion Dawson was told by the Hooker plant manager, a tall, gruff man by the name of Duane Colpoys, that she was probably smelling her “neighbor’s laundry bleach.”

The state had already found high concentrations of chlorinated hydrocarbons in Hooker’s discharge to the lake and warned the company to find the source of the chemicals and eliminate or reduce it. Back came a scathing reply from Hooker: “The most that can be said is that SOME of these compounds MAY be present in the discharge. We will not embark on a corrective design for such inconclusive data.”

The lake, meanwhile, was failing. Aquatic pollution is not usually a dramatic either-or proposition, with all the fish and other kinds of life killed off and the lake declared dead. It is a more steady degeneration with a concurrent rise in species that are resistant to pollution. A biological survey of White Lake in 1975 was compared with samples taken from the same place 23 years earlier.

In the middle basin, which received the brunt of Hooker’s discharge, a grab sample showed there were zero fingernail clams where there once had been 116, and 73 midges instead of the original 3,298.

Perched right up against the lake shore, just south of the Hooker plant, was a tiny subdivision of expensive, dream homes called Blueberry Ridge. Attorney A. Winton Dahlstrom was hired in 1975 to represent a family who had just moved into the neighborhood and was disturbed about the taste and odor of their drinking water, which came from a backyard artesian well. A lab analysis identified three acutely toxic chemicals in the water, all of them by products of Hooker’s C56 operation.

It was not until 1976 that the state threatened to revoke Hooker’s waste discharge permit because of illegal discharges of C56 into the water and air. The company had been spewing 10 pounds of C56 a day to White Lake. Hooker denied the state’s calculations and said the lake was not polluted. You’re asking us to play Russian Roulette, the state said. Prove that your discharges are safe or stop them. Biological surveys of the lake that year showed that half its area was severely degraded and blamed much of it on Hooker’s discharge. After one more year, during which the state bent its rules and allowed the company to discharge chlorinated hydrocarbons into the lake, Hooker shut down its C56 operation, unable to prove its safety.

The company claimed publicly that the cost of producing C56 had become prohibitive. Yet state officials said Hooker simply could not meet the severe and expensive pollution discharge requirements ordered by the state if production was to continue. Hooker was also in an economic bind. The domestic pesticide market was in a slump by the mid- I 970s as the federal governm * ent finally began banning and limiting the use of dozens of dangerous pesticides.

Eighteen jobs were lost when the C56 operation closed and some laid-off employees blamed the local “environmentalists” for the shutdown. “Jobs have always been my biggest problem as an environmentalist,” said Dahlstrom. “I could never make these people believe that jobs don’t mean a damn thing if you can’t drink the water out of the lake or if you can’t produce an edible fish.”

Winton Dahlstrom was an attorney who did not like attorneys, a dove on Vietnam in a town full of hawks, a self-educated environmental scientist who turned his bedroom into a biology lab, and an unbending nonconformist who drove a silver SAAB on streets lined with pickup trucks and fourwheel drives. In his zeal, Dahlstrom antagonized half the town and most of the state regulators. “Wint could talk the spots off a leopard, ” said Marion Dawson, an ally during the early days who has since taken issue with Dahlstrom’s tactics. “Marion is naive,” countered Dahlstrom. “We had an intellectual divorce.”

A month after Hooker stopped making C56, 500 people turned out for a stormy meeting in the Montague High School gym. The town had begun to polarize along ideological lines – pro-industry vs. pro-environment. It was a painful, frightening time. Almost everyone had a child, a parent or a friend who worked at Hooker. The workers closed ranks and united around their company.

There followed a sloppy, dirty-tricks campaign apparently encouraged from within the plant and carried out by some employees and their families. Pressure was put on local businessmen who advertised in the White Laker Observer, the small country weekly which had been closely covering the Hooker controversy. Not only was publisher Darwin Bennett’s business threatened, but the plant manager called him to protest the stories about Hooker. ” I told him I was just trying to do my job,” Bennett recalls. “He said, ‘We have ways of taking care of that, too.’ What did he mean? Who knows. But it was definitely in the form of a threat.”

A group of Hooker wives marched into the local supermarket one day, filled their shopping baskets with food, then abandoned them en masse at the checkout counter. The supermarket had advertised in the newspaper.

Marion Dawson got a telephone call from a Hooker wife who bitterly accused her of causing her husband to lose his job. A family pulled a child out of the class Dawson’s husband taught at the local school. More than once, she had to rescue her young son from the taunts of teenagers who drove past her home, calling out “nature boy” or “tweet tweet” -their crude parody of what an environmentalist was.

The Hooker plant manager threatened to punch Wint Dahlstrom in a local restaurant and a carload of jeering Hooker employees followed one of Dahlstrom’s friends home from the high school meeting. It got so bad, remembers newspaper publisher Bennett, that he and two other friends filed a written statement with the local police department, indicating their fears that someone might try to cause them physical harm.

Bennett had moved to Montague from the smokestacks and chemical fumes of Detroit four years before. “It was like a dream,” he says now. “Here I was moving to this pristine, virginal area.” He sank all his money into the sleepy weekly paper, which suddenly sprang alive in 1976 when Bennett made a “conscious decision to fight this [Hooker] thing tooth and nail.”

Once, he ran a large blank space on the front page of the paper. Inside, he described the pressure Hooker had been bringing on the newspaper and the community. He said he was too small and Hooker too big to fight it anymore. From now on, there woud be a blank space wherever a story about Hooker should have appeared. “The underdog only wins in the movies,” he wrote, “and my name is neither Woodward or Bernstein.”

No one had yet learned about the barrels stacked up behind the Hooker plant. In the summer of 1977, a 28-year-old father of four who had worked for Hooker signed an affidavit describing the location of the barrels and how they had been put there.

Warren Dobson, who had worked in the C56 operation, said Hooker employees had routinely dumped 55 gallon drums of C56 wastes on the ground, that some wastes had been poured from the drums directly onto the soil and killed the trees in an area called “Dead Lake,” that C56 vapors and liquids were routinely allowed to escape from the plant and employees were instructed to say it was “steam,” and that a supervisor once told him: “This isn’t a chocolate factory. We’ve got to make money.” Dobson said he had to tell the story because it was his “duty” as a Christian.

Incredibly, the state did not bother to check the barrels until six months later. When Department of Natural Resources agents found them in March, 1978, the company, according to one state official, “shrugged its shoulders. They said you people knew about this. It’s been here since the 1950s.”

It took several months for the full weight of the contamination to become clear. There was a 15 to 20 acre dumpsite filled with 15 years worth of drummed C56 waste. There was another 15-acre sludge lagoon where three million gallons of contaminated sediment had been dumped. More than 102 chemical compounds were eventually isolated in the waste-“a complete spectrum,” said the DNR’s Jim Truchan, “of all the worst chemicals we’ve got to deal with from the standpoint of environmental contamination.” The state tests showed that the entire plume of groundwater underneath the plant was severely contaminated and moving south, through the backyards of Blueberry Ridge, to White Lake. ‘

More residential water wells were found to be contaminated in Blueberry Ridge and Hooker paid for bottled water to be delivered to the homes. Some $5.5 million worth of pollution control equipment was installed and a purge well dropped to trap some of the groundwater and clean it before it entered the lake.

On August 2, 1978, a state of health emergency was declared hundreds of miles away at Love Canal. “When Love Canal happened, that’s when people really got concerned here,” recalls Darwin Bennett.

Citizens groups were formed and angry letters fired off to Michigan’s governor, the EPA, and other officials. This “period of believing,” as Bennett calls it, continued for the next year as Michigan’s attorney general filed suit against Hooker and negotiations for settlement began. The level of fear escalated when toxicological tests on the Hooker wastepile showed that the chemical gunk was both mutagenic, or capable of causing genetic alterations, and fetotoxic, which means the chemicals were able to cross the placental barrier in rats and damage the fetus. “The potential hazard to human embroyos is clearly there,” the report said.

The report terrified Mary Mahoney, a local Brownie leader who lived on Old Channel Trail, less than a mile from the Hooker plant. Several years earlier, her father died of stomach cancer and her mother developed cancer of the rectum six months later. Then her aunt died of breast cancer and her grandmother got spinal cancer. All four relatives lived across the street from Mahoney, who found herself unable to sleep at night, worrying about something she could not prove. She had a friend in Blueberry Ridge who became so chronically depressed about the toxicological report that she would worry herself into throwing up. The friend would not discuss it but Mahoney knew, and the woman knew, that she had been pregnant with her children during many of the years C56 was produced at the Hooker plant.

The science of linking cause to effect in cancer is tentative at best and this is the kind of reporting that drives Hooker officials mad. “Anecdotal reporting,” Hooker president Donald Baeder calls it, where the press “brings on a woman who I think honestly believes she’s been hurt and you hear her screaming emotionally, ‘What’s going to happen to my unborn baby?’ In many cases, it takes weeks and months, even a year, to find out.”

The state and Hooker reached an out of court settlement in the fall of 1979 on a $15 million remedial cleanup program.

The company installed more purge wells in an attempt to completely halt the flow of contaminants in the groundwater to White Lake. It built a completely clay lined, 800-foot square burial vault behind the plant to contain 1.2 million cubic yards of contaminated wastes and soils. When the top is laid across the vault, a granite marker will be erected that says: Warning -Toxic Material Burial Area-KEEP OUT.

Normalcy

Life goes on now in Montague in normal ways. The anxiety that gripped the town in the wake of Love Canal has leveled off. Most of the town’s people are convinced that the burial vault will safely contain the wastes and that the ground water cleanup program has rescued the lake. The White Lake Chamber of Commerce is launching a big publicity blitz to attract nervous tourists back to town. Warnings once placed on eating fish from the lake are now permanently lifted and the fishermen swarm across its shore. Hooker Chemical Company is still in business, down at the bottom of the hill on Old Channel Trail. “And thank God they stayed here,” says 79-year-old Wendell Lipka. “I never had any trouble. I never had any odor. They’ve been a good neighbor.”

Blueberry Ridge seems quiet now, much like Mrs. Beverly Hunt, wife of the local hardware store owner who used to raise all sorts of trouble about the chemicals trickling down from Hooker’s plant into her backyard. “I’ve put a gag on my wife,” her husband said recently. “I’d rather we not get involved in this anymore. Let’s face it. I’m in business to make a dollar. And Hooker is one of my good customers.”

“It’s like having a retarded sister,” says Darwin Bennett, the newspaper publisher who stopped writing about Hooker when people stopped wanting to hear about it. “No one wants to talk about it.”

Unemployment is 15.3 percent around Montague, the country’s president is preaching the gospel of deregulation and free enterprise, and anti-business news is not what people want to read on the front page anymore. “It got so bad here,” Bennett sighed, “that it was like beating a dead horse.”

There are people who are concerned for the future, but not many people are listening in Montague these days. “You can tell them, if you continue to drink that water, someday you’re going to stand up and your ass is going to stay in the chair,” explains Ed Volk, a local real estate man, in his typically nononsense vocabulary. “Maybe that would get to them. Probably not. But you tell them it’s a mutagen. That it can cause serious damage 20 years down the road. They shrug their shoulders. They don’t understand.”

As for White Lake, it’s healing. Until the lake lays down enough clean sediment to cover the deeply contaminated bottom layer, and until the polluted groundwater is totally cut off, the lake will be polluted.

“I would prefer to see that resource replaced in the condition it was before it was ever impacted,” says John Shauver of the Department of Natural Resources. “But there are not enough dollars in the world to do that.”

©1981 Cathy Trost

Cathy Trost is investigating the evolution of toxic pollution policy in the U.S.