HOUSTON–The clouds hanging dully over Houston have been trying to rain all morning and the air is clogged with humidity. On top of that, Zoltan Merszei, chairman of the Hooker Chemical Company, can’t seem to shake a lingering flu virus. Neither the weather nor disease, however, are capable of trampling his high spirits about the chemical business. Sales and profits on Hooker’s line of fertilizers, soil additives and industrial chemicals are up overall, despite the recession and a slump in chemical commodity prices. The company has just in the past month reached agreement with the federal government on cleanup programs for contaminated chemical waste dumps at Hyde Park, New York, and Lathrop, California, avoiding messy and expensive trials.

Merszei is flying to Los Angeles tonight to finalize details of a major $1.1 billion venture which will bring a number of Italian petrochemical plants into the fold of Hooker and its prosperous parent company, Occidental Petroleum Corporation. “Biggest deal in the history of the chemical industry,” Merszei says with characteristic brashness. The gloom which had settled over the chemical industry in the face of compliance with ever increasing and costly environmental regulations has been offset somewhat by pro-business signals from the Reagan White House. An unintended symbol of that new alliance hangs on the wall not far from Merszei’s office at corporate headquarters here-an autographed picture of President Reagan extending his best wishes to Occidental chairman Armand Hammer.

Business is moving briskly forward on this late winter day at 70 Hooker operations in the United States and abroad and the last thing that Zoltan Merszei wants to think about, the last thing he wants to talk about, is the plague that hangs over the house of Hooker with the same tenacity as does the humidity over Houston.

Love Canal.

“Press reporting of Love Canal has been so scandalous,” Merszei says, biting off his words as he bites off pieces of melon at lunch. “This hate campaign in which Hooker has been viciously attacked is based on distortions of fact, the manipulation of medical data, and the foolishness of some government agencies which have to justify their own existence”

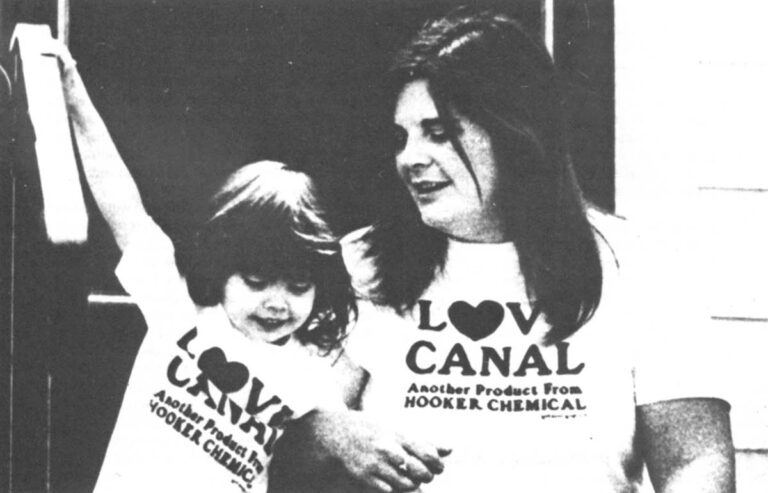

In the same manner that Watergate has entered the English vocabulary as a generic word for government corruption, Love Canal has become the catch phrase to express everything from environmental disaster to corporate ruthlessness. In a complete-this- sentence quiz, hardly anyone in America would fail to attach the words Hooker Chemical to those of Love Canal. It is a shadow that has trailed Hooker since the summer of 1978, when a middle class neighborhood built around an old Hooker chemical waste dump in Niagara Falls, New York, became an international symbol of the industrial sins of the past come to haunt us in the future. The leaking dump was declared a health hazard and more than 230 homes were eventually evacuated and boarded up.

Decisions have been made by Hooker Chemical employees for the past forty years about what to do with hazardous chemical wastes at their plants across the nation. The company’s decisions were not made in a vacuum. They were shaped by the people who lived in towns near Hooker plants and by the local governments responsible for regulating industrial pollution. Forty years ago, the small towns where Hooker built its factories were eager for new jobs. Forty years ago, regulators often looked the other way when industry violated the few anti-pollution laws that existed.

By looking at the ways, then, that we all made compromises in exchange for economic growth and the modern life provided by advanced chemicals, it should be easier to understand how society as a whole failed over the years to confront the inevitable consequences of unchecked chemical production.

Zoltan Merszei runs Hooker Chemical today with an eye toward the future. The past is past, the company pays for its mistakes and moves on. Love Canal, however, is not one of those mistakes. To Zoltan Merszei, the spectre of Love Canal is an annoyance that interferes with his orderly, forward-moving vision for Hooker Chemical. The impatient, Hungarian-born executive is adamant that Hooker operations are run safely and in an environmentally acceptable manner. “Every monthly meeting, two items are at the top of the agenda,” he says. “Safety and environment. Then business.”

Judging the Past

To Hooker executives, who have been ducking verbal blows and working feverishly to counteract the bad publicity, Love Canal is a canal bed used by the company to bury 20,000 tons of chemical residues and then covered with clay. The land was deeded over to the local school board, which had been eyeing it eagerly for new school construction, and all legal liability for future problems transferred from the company to the new owner. The deed warned that chemical wastes were buried there. It did not say what kind or how much. But the wastes would never have percolated to the surface if dirt from the top had not been later removed for fill and the clay cap lacerated by city workers digging sewers through the canal, Hooker officials contend.

The company even sent its own lawyers to school board meetings to remind the board that there were “dangerous” chemicals buried at the site and that the land should not be sold to developers for the construction of homes. Five years after the canal land was sold, the company learned that several children had received chemical burns from playing near the dump, where some of the buried drums had become exposed and were sticking up out of the ground. Inexplicably, Hooker remained publicly silent about the newly discovered danger. The school board was informed, but neither its officials nor those of the company attempted to alert local residents. How long does a company have to look out for property it no longer owns, Hooker officials have since asked.

“We haven’t owned that site for 28 years,” says Hooker president Donald L. Baeder. “We believe that the records will show that Hooker’s actions in every respect with regard to use of that site at that time, the closing of the site, the transfer to the city, the warnings to the city, and repeated warnings, will demonstrate the actions of a responsible company.”

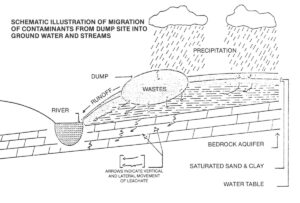

Ironically, Love Canal may in fact have been one of Hooker’s best managed waste operations. While the barrels were lying dormant inside the canal during the 1950s and 1960s, Hooker employees were busily stacking 20,000 drums of toxic waste on top of sandy, porous soil near a Michigan lake. They were filling waste pits and holding ponds with chemical residues at Hyde Park, just over the Niagara Falls city line. With the rains, the ponds spilled over to the ground and through drainage ditches to a nearby creek that feeds the Niagara River. They were discharging what one Hooker employee said was five tons of pesticide wastes a year into the ground in northern California, threatening nearby residential water and agricultural wells. They were letting toxic wastewater slide through sand dumps into Long Island’s chief source of groundwater.

Through a complex combination of cost-effectiveness, expediency and lack of knowledge about the effects of chemicals on the land and on people, decisions were made at Hooker plants years ago that have returned to haunt the company today.

Hyde Park, New York – After Love Canal was filled up in the early 1950s, Hooker began dumping chemical wastes from its Niagara Falls operation on a site just over the city line. More than 80,000 tons of chemical wastes, including substantial amounts of toxic pesticide component residues, were landfilled here. The site would overflow periodically into drainage ditches in nearby Bloody Run Creek, which empties into the Niagara River.

Lathrop, California-Tons of hazardous chemical wastes, including a pesticide later banned by the federal government as a suspected cause of cancer and sterility, were dumped into surface ponds or buried at Hooker’s Lathrop plant for at least 10 years, contaminating the groundwater.

Montague, Michigan-The company stored some 20,000 barrels of toxic C-56 residues on a wooded stretch of sandy soil behind its Montague plant for more than 15 years. The leaching of the wastes into the ground, combined with the downward movement of what the state says was 70 other toxic chemicals disposed of on the site, caused the contamination of nearly two billion gallons of groundwater, which threatened a nearby lake.

The S-Area and 102nd Street Sites, Niagara Falls-Between 1947 and 1975, Hooker used a landfill area adjacent to the Niagara Falls city water treatment plant to bury barrels or dump into trenches some 148 million pounds of chemical residues, including C-56 wastes. On another site adjacent to the Niagara River, organic chemical wastes were dumped through the early 1970s.

Hicksville, Long Island-Hooker discharged water from its polyvinyl chloride resin manufacturing plant, including vinyl chloride and trichlorethylene wastes, through sand sumps into Long Island’s acquifer for 19 years. Numerous private and public wells have been closed on Long Island as a result of numerous sources of industrial contamination by a variety of companies including Hooker.

Taft, Louisiana- Internal company memos obtained by the Securities and Exchange Commission several years ago revealed that methods of waste disposal used by Hooker at their Taft plant threatened to contaminate the groundwater and that a dump area for asbestos wastes was continually flooding.

White Springs, Florida-Hooker voluntarily turned itself in to state and federal agencies for violating pollution laws at its phosphorus plant in Florida. Documents showed that the company had changed a process, thereby releasing more fluoride into the air, in order to cut costs.

Hooker was doing exactly what many other industrial companies were doing with their wastes at the time. They broke no laws because, with the absence of today’s tough environmental regulations, there were few laws to break. They were dealing with industrial chemicals that were mysterious even to the engineers and scientists who supervised their use. Knowledge about the cancer causing and toxic effects of chemicals was sparse.

“I’m sure on hindsight there are things we all wish would have been handled differently in our lives” says Hooker president Donald Baeder. “Were these people as conscientious about the environment 10 or 20 years ago? I don’t think anybody was, because we really didn’t appreciate the impacts that were occurring”

Hooker managers who made questionable decisions in the past are largely still employed by the company today. But most of the people who actually run the company only recently came on board. Merszei himself did not arrive until 1979. The new leadership has demonstrated a commitment to cleaning up their problems and working within the framework of anti-pollution laws.

The company is spending an estimated $15 million to clean up the Hyde Park area and another $15 to $20 million on a remedial program at Montague. A third cleanup operation is underway at Lathrop. One of the agreements has been praised by the government as a “how-to” guide for the industry.

Hooker executives are eager to correct what they consider to be errors of fact and to tell their side of the story. They don’t like to dwell on the past. “It’s just not a good or useful exercise to judge the past by what we feel today,” says Hooker president Baeder.

Yet, repercussions from past Hooker mistakes continue to sound against the environment today. Like many of its chemical counterparts, Hooker’s decisions to dispose of hazardous wastes were often based on concerns about costs as opposed to risks, and what the company or individual managers thought they could get away with in terms of avoiding government crackdowns or escaping detection. The decisions were complicated; they were not, as Lewis G. King, Hooker senior vice president for operations, points out, “simple lives – vs.- bucks” judgments.

For example, the question of waiting until the company’s hand was forced or acting in anticipation of causing a problem was raised in an internal company memo written in 1976. “Do we correct the situation before we have a problem, or do we hold off until action is taken against us?” the memo said. Hooker officials note that funds for pollution control equipment which the memo-writer was requesting had in fact already been approved by management. The pesticides and fertilizer plant in question-at Lathrop, California-is nevertheless the scene today of a major excavation and remedial cleanup program.

“I don’t know of any one of us who would sit here and say let’s put dollars on one side and lives on the other,” King said heatedly. “Are we willing to kill one person? Two? Or maim some people? No, I don’t know of any executive over my 30-year career who has made that kind of judgment.”

Hooker president Baeder created an internal audit program when he arrived at the company in 1977. “One of the first things I did was to say that while I had complete confidence that plant management was obeying all the environmental legislation,” Baeder recalls, “I could not sleep nights until I had an independent audit of that by my staff and headquarters.”

The audit system has been expanded recently to include periodic reviews by Occidental Petroleum board members. In addition, Hooker has spent or committed more than $180 million to environmental programs and $50 million to clean up contamination from past operations during the past three years alone. The company insists it will accept financial responsibility for environmental problems it caused in the past. “If we’re responsible for a problem, then we’re going to solve it,” says Frank Neruda, Hooker vice president for environmental affairs.

The one problem the company absolutely refuses to assume liability for, however, is Love Canal, which is the focus of a $124.5 million federal lawsuit and some $14 billion in private lawsuits.

Ancient Mariners

The albatross of Love Canal refuses to go away, despite the fact the company has no legal obligations for the dump and despite the fact that numerous medical and epidemiological studies have not been able to prove conclusively that exposure of residents to Hooker Chemical wastes was the cause of subsequent health problems. For one thing, most of the studies have been discounted because they were conducted in scientifically questionable ways. For another, cancer is slow to develop. Exposure to hazardous chemicals 20 years ago may not yet have produced tangible evidence of the disease. As a result, there are people at Love Canal who fear for their health or that of their children and unborn children without knowing who is responsible or whether their fears are even founded.

Confirmations and then denials of government-sponsored medical tests and second guessing about the necessity of health warnings and evacuations of Love Canal have produced sizeable psychological stress for the families there.

“You’ve got to feel sorry for these people, the way the government has handled it,” says Baeder.

Clearly, Hooker is taking the offensive after having been down for the count for too long. Negative publicity and fears about the potential cost of litigation have hurt the company’s position on the stock market. “It’s difficult to tell people,” says Baeder, “that we don’t believe these [lawsuits] will have any material effect on the company.” Further undermining confidence was a protracted, mud-slinging campaign waged by the Mead Paper Company in successfully resisting a takeover attempt by Occidental Petroleum. Mead collected reams of confidential Hooker documents and built a case that the company was financially threatened by its past haphazard environmental practices.

Hooker officials contend, with good reason, that their activities have been scrutinized more closely than any business firm in recent history. Put any company under such an unforgiving microscope, they say, and you’re bound to turn up a few problems.

In fighting back, Hooker spent more than $250,000 to place ads in major newspapers refuting critical editorials in the New York Times and Business Week. A deluge of special Hooker publicity pamphlets called Factlines-10,000 in all-were sent to newspapers all over the country with the purpose of setting the record straight on Love Canal. Reprints of a collection of speeches given by Occidental chairman Armand Hammer and Hooker chairman Zoltan Merszei to representatives of the East Coast financial community were also packaged and mailed out. Its title: “The Other Side of Love Canal” *

“Less dullstuff on Love Canal” begs a Hooker employee in an “If I Were Editor” column of the company’s in-house magazine.

The Bright Side

Love Canal was a tragedy for the people who lived there. In a larger sense, though, Love Canal served a useful purpose in educating Americans about the consequences of industrial waste disposal. It also provided the impetus for the much maligned Superfund legislation, which was approved by Congress just before the Carter Administration departed Washington. The $1.6 billion fund, built up over a four year span primarily through fees imposed on the chemical industry, will pay for the cost of cleaning up abandoned hazardous waste dumps around the nation.

Hooker chairman Zoltan Merszei believes that the majority of environmental regulations like Superfund and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act-the first comprehensive federal law to control hazardous waste storage-are more a reflection of the lobbying of special interest groups in Washington than the will of the American public. He defends the chemical industry’s reputation for safety and environmental responsibility as one of the best. In the spirit of staunch free enterprise, Merszei thinks the industry should be left more to its own devices in order to police itself and to create better solutions for pollution control. “Who’s to say that government is more moral than industry?” he scoffs. “There are many crooks in government, many crooks.”

The industry only hurts itself in the end by not anticipating the costs of protecting the environment and then paying them before a problem of even greater magnitude is created, says Merszei, who spent some 30 years running Dow Chemical Company’s international operations.

“You always have to look at the collective good,” adds Lewis King, Hooker vice president for operations. “There are risks in any activity. When you put the balance of risks versus advantages, the chemical industry has produced enormous benefits for society.”

“There have been some risks along the way,” he conceded, “and unfortunately some of them have been perhaps more onerous than people envisioned at the time.”

©1981 Cathy Trost

Cathy Trost is investigating the Evolution of Toxic Pollution Policy in the U.S.