BURLINGTON, Ontario–Klaus Kaiser felt no sense of urgency as he drove east across Canada in the summer of 1973 toward an obscure fishing station called Glenora in Lake Ontario’s Bay of Quinte. The young, German-born research scientist for Canada’s equivalent of the Environmental Protection Agency was simply enjoying a brief holiday on the shores of this calm inland sea called “lake-fine” by its Iroquois settlers.

Kaiser had been doing some work in the area of PCBs, the ubiquitous chemical that was turning up in every corner of the world. His colleagues at Glenora had just caught some fish upstream and Kaiser asked for a few to take back to his lab to test for PCB contamination. He left for home accompanied by a Northern Pike and a Northern Longnose Gar.

Kaiser had no idea of the chain of events he was setting into motion as he drove back to his office in Burlington. Hidden inside the two fish in his car was a clue that would explain the mysterious decline of bird populations in Lake Ontario and set off a warning flare about a significant danger to humans who ate fish from the lake.

His work would eventually lead to the banning in two countries of a dangerous pesticide, the virtual shutdown of the commercial and sports fishing industry in Lake Ontario, and Government Scrutiny of an American chemical company whose name had not yet burst into headlines in connection with a dump called Love Canal.

“Really,” Kaiser says now with the kind of cheerful insouciance not commonly found in research scientists, “I just wanted a day’s outing.”

What Kaiser found in the two fish were trace levels of the chemical mirex, which is one of the most chronically toxic and slowly degrading compounds ever produced on an industrial scale.

What Kaiser found, in a larger sense, was a classic case of industrial pollution in America.

For 16 years, the Hooker Chemical Company discharged mirex wastes into the Niagara River, which feeds Lake Ontario. Mirex infiltrated the delicate food chain of the lake and in doing so, threatened fully sixty percent of New York State’s fresh water supply, which was considered one of the world’s leading fisheries.

What made the story even more classic were these facts: Hooker says it did not know the potential dangers associated with mirex, even though it was commercially marketed as a potent ant killer. Hooker broke no laws by dumping its wastes into the river (which has been used as a giant industrial sewer by numerous companies throughout this century).

Scientists from both Canada and the United States, joined by their regulatory agencies, fought over the evidence. In the end the only consensus that could be reached was that mirex was in the lake.

“Nothing definite was ever done on mirex,” charges Canadian Wildlife Service scientist Doug Hallett. “No controls or action ever went to Hooker to say, ‘Stop doing that.’ Mirex just cleaned itself up, on its own.”

Blame It on Bioaccumulation

The International Joint Commission (which polices the shared waters of Canada and the U.S.) made an unprecedented recommendation that Hooker be sanctioned or fined for discharging toxic wastes into the river and the lake, but no such action was taken. (New York State and the U.S. Federal government did recently reach a 16 million dollar agreement with Hooker for the cleanup of its Hyde Park landfill, located north of Niagara Falls, where 200 tons of mirex wastes are buried.)

“Economically, mirex was a killer,” says Joan Gipp, a member of New York’s Great Lakes Commission and a Lewiston councilwoman involved in the dispute over cleaning up the Hyde Park landfill.

“Commercial fishing used to be a significant industry here,” she said. “I was born here, I remember it. Now it’s banned. As a result, tourism falls off, real estate values drop. And that’s ironic because the Niagara River is why most of us are here.

“Mirex has also bioaccumulated in our fish, and obviously, that’s the bottom line. It’s going to kill our people. I feel that reparation should be made to the people for what was lost to us in the Niagara River, and the lake, and the economy.”

Hooker officials believe the company is blameless. The company ran its Niagara Falls mirex operation under state and federal permits. Wastes were either land-filled or incinerated, according to Hooker spokesman, Michael Reichgut.

“Continuing studies have not detected mirex in plant waste streams or in water samples from the Niagara River and Lake Ontario,” Reichgut said. “Accordingly, we have no data which would substantiate that any significant quantifier of mirex entered the environment from our plant.”

“Furthermore,” he said, “the whole question of mirex in relation to the alleged contamination of Lake Ontario remains an unsolved issue.”

The contamination of Lake Ontario is not alleged, in scientist Klaus Kaiser’s opinion. He knows it for a fact. After Kaiser found mirex in the two fish in 1973, he launched a complicated scientific investigation.

The scientist began to do some detective work. The first puzzle was how mirex had gotten into Lake Ontario. The powerful pesticide had been the American government’s weapon of choice in the war against the tenacious imported fire ant. The borders of that war had been confined to the Southern states, however, and Kaiser could not figure out how mirex had gotten into fish in an isolated part of Lake Ontario.

He started with two theories: mirex spread virulently through the atmosphere like PCBs, or else the contamination was the result of some local company producing or using the chemical.

“When I found it, I had to look it up all in all kinds of books. What is it used for, I asked myself,” Kaiser recalled, climbing across his desk to reach a report in the bookcase on the other side. His small office in Canada’s Centre for Inland Waters is strewn with maps of Lake Ontario, Georgian Bay, and Long Point Bay, plus a rubber tree and a large basket filled with the tall water plant, CYPERUS PAPYRUS.

Kaiser discovered that the chemical mirex was the basic ingredient of the pesticide Mirex as well as a flame retardant used in plastics, which was marketed under the trade name Dechlorane.

The company that held seven patents on mirex dating back to the early 1960s was Hooker Chemical Company of Niagara Falls, New York. Several other firms had patents for mirex, too, but their plants were nowhere near Lake Ontario.

Even though Hooker’s factory was located in Niagara Falls, the company was still “250 kilometers away from the site of the contamination” in the Bay of Quinte, Kaiser reasoned. Without completely solving the puzzle of how it had gotten there, Kaiser published his report on mirex in the lake fish in 1974.

The news inspired no particular outcry, partially because Lake Ontario had been fighting an uphill battle for years against pollution–first, the suffocating algae and phosphorus, then the onslaught of organic chemicals like DDT and PCB. In another sense, the news that a Canadian scientist had found a chemical in several fish simply wasn’t dramatic enough to shake people awake.

Still, the pieces of the puzzle were slowly dropping into place. The same year that Kaiser first published his mirex report, other scientists were unwittingly documenting the devastating chain reaction that mirex had already caused to occur in the lake’s delicate web of life. Research in 1974 chronicled the dramatic reduction of successful breeding among the lake’s Herring gulls and a high rate of birth defects among those gull chicks who beat the odds and were born.

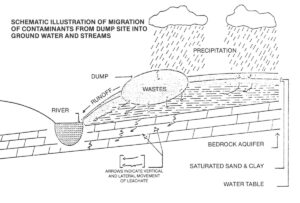

A persistent but slow-acting poison, mirex had infiltrated the lake water and laced the bottom soil sediments. Insects ate the bottom plant life, and forage fish like alewives ate the insects. The alewives then swam to other parts of the lake, where they were eaten by larger fish like salmon and trout, which were eaten in turn by birds.

Fish-eating birds like the Herring gull stand on one of the last rungs of the food chain. Because they have a particular biological talent for concentrating chemicals in their bodies, and because they live chiefly in the Great Lakes area and nest together there, the gull is a perfect indicator species for pollution in the lakes.

The relentless climb of mirex up the food chain still wasn’t clear in 1975 when Canadian Wildlife Service scientists Doug Hallett and R. J. Norstrom began their landmark studies of Herring gull populations in the lakes. They found that the number of chick embryos that never hatched was much higher than normal. They also found the ability of gull chicks to live longer than 21 days in Lake Ontario nesting colonies was only a tenth of normal.

The biggest pieces of the puzzle–how widely mirex was distributed through the lake and where was it coming from–began to be fitted together by a colleague of Kaiser’s at the Canada Centre. Dr. Richard Thomas had frozen some soil samples he’d taken from the lake sediment back in 1968. On a hunch, Thomas dug the soil plugs out of the deep-freeze and looked at them again, this time for mirex.

Mirex was there, captured in time. When the soil plugs were plotted against their original locations in the lake, two distinct zones of mirex contamination became clear. One zone, stretching along the southern shore of the lake, showed high levels of mirex coming from the Niagara River, which feeds the vast majority of water into Lake Ontario. The other zone dipped down from the mouth of the Oswego River in the eastern part of the lake.

Mirex was obviously shooting into Lake Ontario from the Niagara and Oswego Rivers. The question was, from where? Hooker seemed the logical source of mirex on the Niagara side, but the Oswego source was a mystery.

While scientists worked behind the scenes, the long-simmering controversy over mirex flared into public view in July, 1976 when the Canadians stunned a meeting of the International Joint Commission with the news that virtually all species of fish in Lake Ontario were contaminated with mirex.

Within a matter of days, the Canadian government issued a warning about eating fish from the lake. The American government, meanwhile, launched a hasty investigation of Hooker. “Existing information,” announced New York State authorities, “indicates that Hooker was the major source of mirex to Lake Ontario.”

Records showed that Hooker’s giant plant in Niagara Falls was the sole producer of mirex in the United States from 1959 to 1967. After that, Hooker licensed production to a company in Pennsylvania, which sent mirex back to Hooker for grinding and packaging. The entire operation came to a halt, Hooker said, the year before, in the spring of 1975.

Hooker spokesman, Michael Reichgut, said the standard cleanup procedure for mirex wastes called for the collection of the wastes, including the water used in the cleanup program, and land-filling or incinerating the wastes.

An Environmental Protection Agency report from 1974 tells a different story.

An EPA investigator watched Hooker grind up 3,000 pounds of mirex in a courtesy demonstration. He said the dust from the grinding operation was washed from the equipment and off the floor with a high-pressure water hose. The wastewater was flushed into a gutter, which poured into a municipal sanitary sewer.

In other words, mirex wastes were funneled through the sewer directly to the Niagara River. Hooker was also discharging about 24 million gallons a day of process wastewater, which included mirex, into the sewers. Both operations were entirely legal.

“I would estimate,” the EPA’s investigator wrote in 1974, “that a minimum of 20 pounds of mirex per year have been discharged to the Niagara River for the past 15 years.” The state later upped that estimate to nearly one and one-half pounds a day of mirex–a figure which was challenged, however, by three laboratories, including the EPA’s.

The state further learned that some 200 tons of Dechlorane, or mirex, wastes were buried in Hooker’s Hyde Park landfill located several miles north of the plant. Tests showed that chemicals were leaching from the landfill and contaminating the soil of a nearby creek called Bloody Run, which fed into the Niagara River. The dump had been actively used by Hooker until 1975, and for most of that time, it had been inadequately secured.

By 1975, the scientific evidence against mirex was piling up. Studies showed that mirex produced cancerous tumors in mice and caused deadly interference with animal reproduction by building up in the mother’s tissues and invading the placenta and fetus.

“Mirex,” said one report, “will usually preferentially migrate to portions of the environment that are high in fats and oils. Since most biological organisms contain fats and oils, it tends to, over a period of time, accumulate in them at a much higher concentration than exists in the water environment.”

“Mirex,” said another report, “has one of the highest chronicity factors of any pesticide,” meaning that it can linger for long periods of time in the fats of a fish or a herring gull, causing sickness and death years after the initial exposure.

In 1975, Hooker voluntarily withdrew from the mirex market when it became known, according to Reichgut, that mirex “had a tendency to persist in the environment and animals.” The remaining inventory of mirex was sold to manufacturers in South America, where the product is still used to control fire ants.

Back in Canada, meanwhile, the scientists were still trying to track the source of mirex in the eastern part of Lake Ontario. Dr. Thomas traced the path of his 1968 soil samples and found that the mirex contamination was just as heavy in 1976 as it had been eight years before. He presumed that Hooker was responsible for the mirex in the Niagara River, but what about the Oswego River?

Through skillful examination of the soil sediments along the Oswego River bed, Thomas tracked the mirex discharge to a company called Armstrong Cork, which sat on the river a short distance upstream of Lake Ontario. Armstrong bought mirex from Hooker to use as a fire retardant in its manufacturing processes. By looking at the rings of increasing mirex concentration that circled one of his soil plugs like the age rings on a tree trunk, Thomas calculated that a quantity of mirex had been discharged from the cork plant some 15 years before.

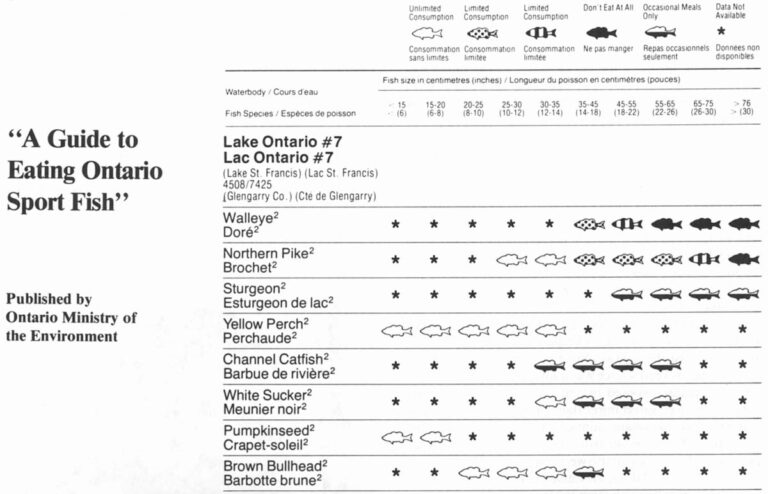

News of the widespread fish contamination, the Canadian warning against eating Lake Ontario fish, and the linking of mirex discharges to Hooker all occurred back-to-back in the summer of 1976. In the fall, the state of New York dropped another bombshell when it issued a total ban against eating certain fish from the lake because they were so badly contaminated with mirex.

The ban included coho and chinook salmon and lake trout–all large game species that were highly prized by sports fishermen. White bass, white perch and smelt could be eaten only once a week. Pregnant women and infants were ordered to eat no fish at all.

The ban destroyed what was left of the lake’s commercial fishing industry and put a serious crimp in the profitable game-fishing business. The ban was wildly unpopular among fishermen and some local officials, and business people, who depended on the $30 to $45 million boost that sports-fishing gave the state’s economy. The ban was also announced just one week after the state had begun an expensive fish stocking program in the lake. The result: one state agency was dropping fish into the lake that another state agency was branding as too dangerous to eat. The stocking program abruptly ended.

To the anglers, it seemed just another foolish example of government intervention. They couldn’t see or taste the mirex in the fish and after they ate it, they didn’t feel sick.

“You can eat a whole spoonful of mirex and not feel any immediate effects,” explained Klaus Kaiser. “Mirex is known to produce effects long, long after you are exposed to it.”

The politically sensitive scientific debate raged on, degenerating at one point to a cat-fight between state agencies as to whether a human could safely eat 100 or 175,000 mirex-contaminated fish in his lifetime.

The full scope of mirex’s danger was eventually communicated through the scientific and regulatory groups to the Canadian and American governments and, by 1978, mirex was totally banned in Canada and outlawed as a pesticide in the United States.

But just as the two federal governments were clamping down on mirex, New York State was loosening up. Reeling from the financial drain caused by the fish-eating ban and under huge pressure from almost every quarter save for its health advisors, the state lifted the ban in March, 1978. Governor Hugh Carey called the ban “a major goof” and replaced it with a public health advisory.

Officials would later explain that eating Lake Ontario fish was “primarily a voluntary risk, not unlike the risk assumed by the cigarette smoker.” The fish stocking program swung back into action the following year.

The Canadian researchers, meanwhile, had been working backwards in time, using frozen fish, eggs, and soil samples from the 1960s to build a 10-year graph of mirex contamination in Lake Ontario. They built a strong case that Lake Ontario herring gull eggs were the most contaminated of any gull eggs in the Great Lakes basin.

Will Mirex Always Be With Us?

“Much of the widespread contamination of aquatic birds in the Great Lakes area is a result of the presence of mirex in Lake Ontario water and fish,” said Canadian scientist Doug Hallett, who found mirex as high up the food chain as the peregrine Falcon, which feeds on migratory birds.

By the end of the 1970s, Hallett and his colleagues were noticing a startling trend. The general rate of mirex contamination on that 10-year graph was falling. The Herring gull colonies were showing dramatic improvements in breeding success. The scientists theorized that the improvement was paralleled by equally dramatic decreases in mirex and other organic chemical residues in the lake itself.

Today, the rate of contamination is falling, but the levels of mirex in the fish are still high. Scientists believe it is a good sign that the lake is slowly ridding itself of mirex.

Many scientists also believe that once Hooker stopped processing mirex in 1975, the lake started to clear itself up. The mirex-laden sediments are slowly being covered by new layers, and the water volume in the lake itself, which completely turns over every eight years or so, has been replaced by new water.

Individual species of fish in the lake remain high in mirex and the New York and Canadian governments continue to maintain health advisories on eating the larger, fatter game fish from the lake.

“I personally prefer not to eat any fish from Lake Ontario,” admits Klaus Kaiser.

Kaiser is too impressed by mirex’s persistence to think that it has so easily been cleaned up. “Mirex is essentially going to stay around for quite awhile,” he predicts. “It will stay in the lake for hundreds of years, not to say thousands of years.”

Hooker officials believe that the confusion over mirex levels in the lake and the rescinded fish ban are evidence that no one really knows what effect mirex has had on the lake.

“The presence of relatively high concentrations of PCBs in Lake Ontario, for example, has been repeatedly confirmed by scientists in the U.S. and Canada,” spokesman Michael Reichgut said. “However, the difficulty in identifying and quantifying other materials, such as mirex, has been the subject of much work as well as technical disagreements among respected scientists.”

He cited studies which show that mirex is not present in the Hooker plant discharges to the river or in water samples from the lake and river.

(Because mirex migrates towards fats in the environment, it tends to accumulate in fish and birds at much higher concentrations than in the water itself.)

Moreover, Hooker refuses to be labeled as the major source of mirex to the lake, as New York State officials have charged. “We have not seen any data,” Reichgut said, “that would support this assumption.”

Researchers are hopeful that gains made and lessons learned from the seven-year struggle with mirex will hasten a solution to the other chemical problems, such as the deadly dioxin, which has recently been found in lake fish and gull eggs.

“People understand environmental contamination much better now and they are taking action quicker now,” says Hallett. “When we first came up with TCDD [dioxin], people would say to me, ‘What’s the big deal, Hallett?’ “

“Now they say, ‘Right, that stuff is nasty.’”

The water world of the lake and the animals that it nourishes are fragile. Despite the best intentions of science, this tenuous world can break apart with little warning. Lingering fears about mirex were dredged up this year when scientists found that upstate New York waterfowl were chemically contaminated, and warned hunters not to eat more than two meals of duck a month.

But even that precaution may not be enough. One fish-eating Merganser duck from Lake Ontario was found to contain a mirex level 25 times the federal safety limit. The beautiful crested bird with the long, slender beak is so poisoned with mirex, scientists said, that it should not be eaten at all.

©1981 Cathy Trost

Cathy Trost, a reporter on leave from the Detroit Free Press, is investigating the evolution of toxic pollution policy in the U.S.