LEWISTON, N.Y.–During the 1950s, a decade that would come to be remembered by many as an uncomplicated, golden time when the market was bull and what was good for General Motors was good for the country, Hooker Chemical Company paid $48,000 for a strip of swampy land about six miles north of the rushing waters of Niagara Falls and began filling it up with chemical waste.

Like the rest of the country, Hooker was growing prosperous. It produced more wastes from its thriving industrial chemical business than it knew what to do with. The company acquired three smaller chemical firms in the space of two years and strengthened what would eventually become a 250-chemical production line at its big, belching Niagara Falls plant. Residues from that plant had already filled up a trench called the Love Canal on the eastern edge of the city.

Looking around for a new dumpsite, Hooker found the marshy strip of land just below the Lewiston city line in the township of Niagara. Just a few miles to the north were the spectacular cliffs of the Niagara Gorge, which sloped dramatically into the Niagara River as it snaked down from Lake Ontario, but the area closest to the dump itself was largely rural and undeveloped.

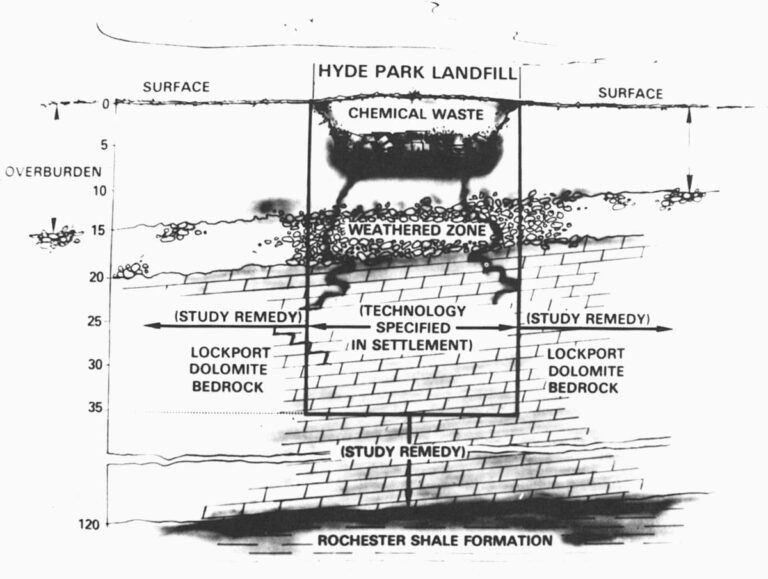

The landfill that Hooker bought as a replacement for Love Canal in 1953 was called Hyde Park after the boulevard that ran past its edge. Hooker sold off some of the land, which had been used in the past as a garbage dump, and kept a 16-acre plot that was roughly triangular in shape.

During the next quarter century, the Hyde Park dump would come to hold nearly four times as much toxic chemical waste as Love Canal.

It would also become a bitter environmental battleground where local residents and city officials joined together to fight Hooker, the State of New York, and the United States government.

Now, convinced that their health and safety were shortchanged by a government–negotiated cleanup agreement with Hooker, this opposition has delayed for the past eight months court approval of the $15 million settlement.

“The government’s role in the negotiations was one of advocate of Hooker and adversary to our residents,” declares Joan Gipp, a Lewiston city councilwoman.

“I pray and hope,” adds Lawrence Maillet, who played in the dump as a child, “that someone can stop this giant corporation that wants to spend $15 million on a cleanup when they made $15 billion by contaminating the whole environment around the dump. It is a sin.”

The federal government negotiators and the state of New York attorneys who spent 10 months shaping the agreement believe it is “the most comprehensive and far reaching resolution of a hazardous waste case to date and is one of the most complex and sophisticated environmental settlements ever reached.”

Buying Homes

The dispute over the settlement boils down to this: the residents want the waste dug up and buried somewhere else and the homes around the landfill evacuated. The government wants to leave the waste in the landfill and surround it with pumps to suck up the contaminated water for collection and decontamination.

Both the government and Hooker are convinced that digging up the chemicals would be asking for trouble. The settlement calls for Hooker to do wide-ranging tests to figure out how far down and how far out the chemicals have migrated from the dump site. Then, the company will design the best program for fixing the problem in conjunction with the state and federal environmental protection agencies.

As Frank Neruda, Hooker vice president for environmental affairs, said: “I have been given carte blanche to do the job and do it right. We won’t agree to do something that will in fact be stupid, technically.”

The opposition doesn’t like that plan. They think the chemicals are escaping through cracks in the thick bottom layer of bedrock and they don’t think the remedial program takes that into consideration. They also want everyone moved out of the neighborhood around the creek before cleanup begins. The government says that’s not necessary. Hooker has agreed to buy nine homes in an attempt to settle the dispute.

The bottom line, as far as the government is concerned, is getting the dump cleaned up. Negotiators point out that compromises have to be made in order to settle any difference. This agreement avoids a long court trial and more time lost to negotiation while the chemicals fester in the dump.

“Fifty years from now, when hundreds of other dump sites in the country will be dealt with, we may all look back on this and say, you know, what an old fashioned technique, what were-we doing there? But this is the first step. It has to be taken for us to reach that [point] a hundred years from now,” Mary Ellen Burns, one of the New York negotiators, told a public hearing last spring.

Harvesting the Dump

An old fashioned technique is what got Hooker into trouble in the first place. The best waste disposal technology in the 1950s was simply to “find an open hole, put it in there, and cover it,” according to Fred Olotka, Hooker’s industrial waste supervisor. “This happened all over the nation. We are not alone.

“I spent 25 years starting plants up. So I know the industrial end, how to run a chemical plant, no matter what it is. And I never particularly worried, as no one did, about where the wastes were going. You call up the yard, the truck comes along, you fill up the drums, and the drums go out.”

The smattering of people who lived near the dump site also weren’t worried. It wasn’t really a neighborhood, just a few, simple, boxy houses built on Sherman and Belvedere Avenues about a quarter mile north of the dump. The land was little more than a rural field filled with cattails and swamp grass.

One of the early residents remembers harvesting grain on the land where the dump now sits.

But it was a pretty patch of land, a haven of “peace and seclusion” to its residents. They learned to live with the swampy overflow from a tiny creek called Bloody Run, which drained water from Hooker’s dump every time it rained. They also learned to live with the gradual industrialization of the land around the dump. Three small factories were started up in the area between the dump and the little neighborhood in the 1950s.

The people who lived there were not very curious about the dump itself, because, in their eyes, it looked like a common garbage dump. They were also caught up in the spirit of the times, when economic prosperity overshadowed questions about industrial waste and its effect on the environment.

The 1950s was a time of abundance, when the United States was producing half the world’s goods, when The Power of Positive Thinking and How I Made $2 Million on the Stock Market were best sellers, when the profit motive was sacred and Americans, as one historian said, were locked in the throes of “galloping capitalism.”

What mattered most about chemicals was only that they worked–killing insects, protecting agricultural crops, combining in all sorts of mysterious ways to make dyes and paints and perfumes and plastics. Hooker’s chlorine helped to make laundry bleach and household cleaners. Its caustic soda was used in the manufacture of everything from soap to cellophane. Lindane, one of the company’s biggest selling insecticides, was sprayed from portable vaporizers into homes and offices and restaurants to rid them of bugs and moths.

The wizardry of chemicals so captivated American business and its customers that few people stopped to ask questions about potential harmful effects. Years later, after the revelations in Silent Spring and other anti-pesticide books. people began to demand environmental protections. It was still important that chemicals worked, but they had to work in safer ways.

No one, save for the rare scientist or chemist, was completely aware of the long-term effects of most toxic chemicals. In the jargon of the early 1950s, DDT was not a brutal pesticide but shorthand for a popular teenage insult: Drop Dead Twice. It wasn’t until 1954, the year after the Hyde Park landfill was activated, that the first authenticated reports linking cigarette smoke to heart disease were publicized. That same year, the U.S. government exploded its second hydrogen bomb in the Pacific Ocean. Scientists who warned of the dangerous effects of radioactive dust on future generations were publicly degraded as “alarmists” by the Eisenhower administration.

Sweet Potatoes and Peanuts

Prosperity was what Americans wanted and Hooker was helping to supply it. The company started making three major pesticide ingredients during the late 1940s to satisfy the country’s insatiable demand for crop, household and lawn sprays.

The Niagara Falls plant churned out major quantities of C56 (hexachlorocyclopentadiene), which was the building block of dozens of pesticides such as the roach-killer Kepone and the fire ant-killer Mirex.

Two other big-sellers were benzene hexachloride and trichlorophenol. Benzene hexachloride was sprayed on sweet potatoes and peanuts from California to North Carolina to control insects. Lindane, a close relative to benzene hexachloride, was used both inside and outside the home to get rid of pests. Lindane and benzene hexachloride are among the chemicals most commonly linked to leukemia. Lindane was eventually shown to accumulate in the brain and liver tissue and damage the central nervous system.

Hooker voluntarily withdrew its government registration for benzene hexachloride in the mid-1970s after laboratory tests showed that rats fed the chemical developed tumors and reproductive effects.

Another important product was trichlorophenol, a wonder chemical that seemed to solve dozens of human problems. It was manufactured all over the world for use in herbicides to clear both Vietnam jungles and American roadsides of vegetation. It was also a major ingredient of disinfectants like hexachlorophene, which was used to scrub down everything from swimming pools to newborn babies.

Scientists eventually discovered that the manufacture of trichlorophenol produced a contaminant known as 2,3,7,8-TCDD. This insidious white crystalline solid is one of the most powerful toxins ever made by man. It causes cancer, birth defects, mutations, and the death of fetuses in lab animals. The force that TCDD packs in small quantities is more potent than botulism, more lethal than shellfish toxin.

Hooker abruptly stopped making trichlorophenol in 1972. One of the company’s managers told a town council meeting the reason why: “We made trichlorophenol that went into the manufacture of hexachlorophene. They stopped the manufacture of hexachlorophene some years ago because of the fact that several babies were noticed to have brain damage. We immediately, as soon as we heard that, went out of the trichlorophenols business.”

With so much apparent ignorance in the chemical industry, it was little wonder the people who lived near the Hyde Park dump were unconcerned. Day after day, trucks would unload their burden of barrels into open holes dug out of the earth and then backfilled. But to the people who lived there, the barrels looked like common metal drums that held the usual scrap metal and paper garbage from industry.

Daniel Mazaika built his home on Belvedere Avenue three years after the Hyde Park dump opened. It looked to him then like, “a mere garbage dump.” It grew over the years into “this hideous mound of destruction as it is today.”

Eventually, the dump would rise to a height of nearly 15 feet with its load of 80,200 tons of chemical debris. Among the wastes were 5,600 tons of C56 and its derivatives, 200 tons of the fire ant-killer Mirex, 2,000 tons of the cancer-causing benzene hexachloride and Lindane and, most worrisome of all, 3,300 tons of trichlorophenol.

Scientists estimate there is as much of the deadly TCDD in the dump as there was in the Agent Orange herbicide sprayed over the Vietnam jungles during the entire war.

Helter Skelter

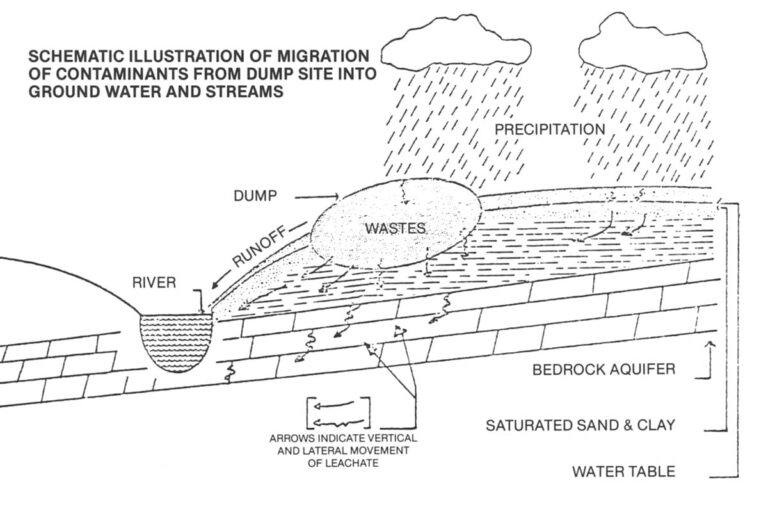

The landfill’s surface was a mixture of sand, silt and clay that descended to a layer of partially decomposed rock. Underlying the whole area was a 100-feet thick sheet of bedrock that was laid down millions of years ago when North America was covered by a vast ocean.

Underground rivers of groundwater ran through the sandy top layer and also through the cracked bedrock toward the Niagara River, less than two miles away. On top of the land, rains and melting snows skimmed across the landfill, picking up a chemical load, and then spread out through drainage ditches to Bloody Run Creek.

The creek flows helter skelter from the dump and down through a storm sewer underneath a nearby barrel plant, then up again and past the little neighborhood on Belvedere and Sherman Avenues, until it is diverted into a storm sewer and emptied into the Niagara River, which itself empties about seven miles downstream into Lake Ontario.

Fred Armagost lived just a few feet from the creek in his house on Belvedere Avenue, where he raised 10 children and some of his 10 grandchildren, who played in the creek. “Wayne and some of the other boys would go down there and get on inner tubes and fall off,” Armagost recalled. “If they would fall off, they would just swim in the stuff.”

The dump itself was used as an illicit playground. “I used to play all around this dump when red, green and other rainbow-colored chemicals were flowing everywhere,” remembered Lawrence Maillet, now 29. “A friend of mine brought his German Shepherd dog along one time and it died three weeks later.”

Grief Brothers

The area around the dump gradually turned industrial. The yard department of National Lead Industries ran right up against the borders of the landfill. Niagara Steel and Finishing, a welding and fabricating shop, abutted another corner of the dump and Grief Brothers, which made drums and sold them to Hooker, was located just to the north. Bloody Run Creek flows underneath Grief Brothers through a sewer pipe.

Because they worked so closely to the dump, the yard workers at National Lead were the first to notice the odors and fumes. Carl Sabey, who worked in the yard department during the 1950s, described how fumes from the dump would make his eyes water and his skin burn. One night, the fumes apparently reacted with fresh paint on the front office walls. “The next day,” Sabey said, “the paint looked like it had been burned. It looked as though somebody took a blowtorch and went over it.”

The people who lived near the dump didn’t know much about the chemicals buried there, but they could tell from the stinging fumes and the disappearance of wildlife along the creek banks that something was wrong. Almost everyone in the neighborhood that bordered the creek had noticed by the 1960s that the tadpoles and green frogs were gone from the creek and the toads and snakes were absent from nearby gardens.

Fred Armagost’s goats got loose one day and went down to the stream for water. They died several days later, he says. His grandchildren continued to play in the water and drink from the well sunk behind their house. His son, Wayne, who had frolicked in the creek years before, developed chronic pulmonary problems. Six of Armagost’s grandchildren eventually required medical treatment for severe respiratory problems. Dr. James Dunlop, who treated the impoverished Armagosts at reduced rates, testified before a Congressional committee in 1978 that he believed the illnesses were a direct result of the chemicals in Bloody Run Creek.

As the landfill grew bigger during the 1960s, more and more people complained about the smells and the fumes. The state health department took samples of the brown and green algae from the creek in 1964, thinking that the algae was the source of pollution. Three years later, a county health inspector reported that drums of chemical wastes were seeping into the creek.

It was during this time, too, that workers at the three nearby plants developed health problems that seemed to exceed the normal amounts of illness one would expect to strike several hundred employees. A subsequent union survey listed skin lesions, respiratory problems, nerve damage, cancer, and the inability of some wives to carry babies full term.

A federal health study reported this year, however, that there were no excessive health problems among the workers. The report said no conclusive link could be drawn between the workers’ health effects and exposure to chemicals in the landfill. Yet, quantities of TCDD, Mirex and Lindane were found in the dust on the rafters of all three plants.

Making the Link

“What does the state and federal government call an immediate danger, when you breathe contaminated particles and drop dead all at once or breathe it in and it shortens your life span by 10, maybe 20 years!” asked a group of angry workers in a letter to the judge who must approve the cleanup agreement.

When Fred Armagost listens to the rasping of his granddaughter, he can only believe that the Hooker chemicals caused her respiratory problems. When a worker at the barrel plant gets cancer, his family points an accusing finger at the same chemicals. But scientists and doctors are not ready to make that link.

Doctors are hesitant to say that health problems around chemical dumps are a result of an exposure to the toxic wastes. They are willing to say only that health problems are the result of a wide range of exposure to dangerous things in the environment–cigarette smoke, asbestos, car fumes, as well as industrial chemicals.

When the county health department threatened to shut down the Hyde Park dump in 1971, it wasn’t because of fears about the effect of chemicals on people, but because the dump violated sanitary codes. The threat came at the end of a decade of complaints by residents and workers. Hooker reacted quickly. The Niagara Falls plant was sending 70 percent of its chemical wastes to Hyde Park and the landfill was crucial to operation.

High Levels of Mirex

Hooker spent $500,000 to fix the landfill and build a storage pond on top of it. The company also installed the equivalent of a drainage pipe to collect the surface water as it skimmed off the dump and pumps to send it over to the storage pond. Clay was spread over the surface and a fence put up. It was a good plan. It was even, as one company official bragged, a plan that was ahead of its time in terms of what state and federal regulations then required. The problem was, it didn’t work.

“The job that was done was not a good job, which we are finding out,” Frank Olotka, Hooker’s industrial waste supervisor, said in 1978. The clay seal wasn’t deep enough to prevent penetration of the landfill by rain and snow. The slope of the landfill itself wasn’t properly engineered. Instead of the rainwater sliding off the landfill and into the drainage pipes, it slid directly into the dump itself and into the ground below. Sometimes the dikes around the storage pond ruptured, sending chemical-laden water pouring into the ground and into the creek.

As the environmental awareness of Americans grew during the 1970s, so did the suspicions of the people living and working around the Hyde Park dump. Yet they were kept in the dark about many of the alarming discoveries made by state and federal government tests regarding the chemicals. The federal Environmental Protection Agency knew as early as the summer of 1976 that the fire ant-killer Mirex had contaminated soil near the landfill, or migrated from the dump itself. The following year, the state found positive evidence that chemicals from the dump were moving through Bloody Run Creek. High levels of Mirex were found in the bottom soils of the creek just 50 feet north of Sherman Avenue.

Hooker insisted that the groundwater and surface water could not be contaminated with chemicals from its dump. It pointed a finger at the industrial chemicals used by the three small companies next door. It said soil conditions were such that its chemicals could not cut through the ground and reach the water. It claimed that all chemical waste dumping had stopped at Hyde Park by the end of 1974.

In 1978, Hooker’s own consultants found that Bloody Run Creek was contaminated with organic chemicals that could only have come from the Hyde Park dump. One of them was TCDD, one of the most toxic chemicals known to exist.

That’s when Lewiston councilwoman Joan Gipp began to suspect that something was terribly wrong. She intercepted one of Hooker’s letters to the EPA about the TCDD contamination and started asking people questions. “I wasn’t aware of the magnitude of the Hyde Park dump until 1978, when I got Hooker’s confidential reports,” Gipp says now. “Then I realized for the first time how lethal it was.”

How much Hooker knew about the contamination and for how long is unsure. A new wave of corporate administration had taken over Hooker during the mid-1970s and they seemed more committed than their predecessors to environmental responsibility. Part of that new spirit resulted in an internal audit of the Niagara Falls plant in 1975 called “Operation Bootstrap.”

“Bootstrap was saying, look, how can we pick ourselves up by the bootstraps and do a much better job in running this plant, not only more economically, but more safely, more environmentally acceptable,” says Donald Baeder, former president of Hooker and now vice president of science and technology for Occidental Petroleum Corporation, which owns Hooker.

The Predictions Came True

Bootstrap was a candid, thorough report that outlined serious problems and offered no quick or easy solutions. It warned that federal and state regulations on chemical landfills were inevitable in the years to come. It observed that major decisions about pollution control had been deferred by corporate management in the past and made a strong case against doing that in the future.

Within three years, Bootstrap’s predictions about regulations had come true. In 1978, Hooker worked out a plan to bring the leaking Hyde Park landfill into compliance with state environmental rules. The state tentatively approved the $1 million program but warned that the plan was still “not good enough.”

Hooker made improvements that it says cost $2 million but the state, and by now the federal government, still weren’t satisfied.

The contamination and evacuation of the neighborhood around Hooker’s old Love Canal dump in 1978 had attracted international publicity and cost the state and federal governments a great deal of money and a great deal of aggravation. Two other dumpsites used by Hooker in Niagara Falls were also causing problems. More than 70,000 tons of chemical wastes had been dumped in the S-Area, which was located next to the city’s drinking water treatment plant. More wastes had been buried in a nearby dump called the 102nd Street site.

In late 1979, the federal government filed a $126 million lawsuit–the largest environmental lawsuit in U.S. history–against Hooker to force cleanup of Love Canal, Hyde Park, and the two other dumpsites. The State of New York followed with its own suit, which was subsequently joined to the federal action.

A Lot of Talk and Some Action

Hooker officials were infuriated with the Love Canal accusations because they believed they had closed the dump in a safe manner and sold it to the local school board with ample warnings about the chemical waste buried there. They were also enraged that legal action was taken against the three other landfills, but for another reason.

“We want to remedy the landfill problems that exist in the Niagara area that are our responsibility,” Occidental vice president Donald Baeder explained. “Those are our properties, our land, and we are anxious to get on with the remedial work.”

Just before the federal lawsuit was filed, Baeder went to Washington to talk with James Moorman, the Justice Department’s assistant attorney general handling the case. Baeder had a copy of the cleanup plan that Hooker had developed the year before for Hyde Park. “I pleaded with him to continue negotiations to get this [plan] implemented quickly,” Baeder recalls. “It was to no avail. They brought suit.”

Hooker officials attacked the government suit as “unwarranted and unjustified” because, as Baeder explained, “they slowed us down from what we know needed to be done, from what we had already put money aside to do. In fact, I took the money out of 1980 earnings and put aside this money to do Hyde Park, and money to do the S-Area, and money to do 102nd Street.”

Ten months after the suit was filed, the government announced agreement had been reached with Hooker last January on a cleanup plan. There was mixed pleasure among Hooker officials. “Now we’ve spent a whole year,” Baeder said, “and literally this [cleanup] program is not different in substance from what our people had proposed a year and a half ago. And meanwhile we’ve spent a lot of money and the government has spent a lot of money in negotiating this.”

We’re Stewards of the Earth

Government negotiators disagree. The current settlement is a substantial improvement over Hooker’s original plan, they said, and bringing suit was “the best way” to get the kind of cleanup program they wanted.

In a strange alignment, the two governments (state and federal) and Hooker are now working together to win support for the agreement. “This is a precedent-setting agreement and truly a model for industry,” says Frank Neruda, Hooker’s vice president for environmental affairs. “It is a manual, almost, of how to look at any [landfill] problem.”

The government and the company made compromises to reach an agreement. Now they are asking the people of Lewiston to make compromises in order to put that agreement to work.

Joan Gipp is a politician and she knows about compromise.

But, she says, “you can’t compromise with human beings. You can’t compromise with health. You go on up there and talk to Fred Armagost, who has 10 children and 10 grandchildren and watch that man as he’s standing there with his granddaughter, saying that she’s sick. Some things are just not negotiable.”

Gipp is an open-faced, motherly woman with two college-aged boys. Her coal miner father brought his family to Lewiston from England to escape the black dust. Now the beauty of this riverside town is marred not only by the Hyde Park dump, but the contaminated Niagara River and, not far from Gipp’s home, a government storage silo for atomic waste.

“Lewiston is 65 square miles of the most beautiful land you can imagine,” she says with genuine passion. “I’m responsible for the government of this town and I look down and I see all this land that is damned forever, that men can never again use.

“It’s almost a religious thing, though I am not a Bible person,” she adds. “It’s just that we are stewards of this earth. And these things are blots on the earth.”

©1981 Cathy Trost

Cathy Trost, a reporter on leave from the Detroit Free Press, is investigating the evolution of toxic pollution policy in the U.S.