* Names have been changed to respect certain individuals’ anonymity.

May, 1971

The best way to understand the past and present of the Maghreb is to regard it through the prism of the history of its Jews. Among all the races of the Maghreb today, only the Jews, while retaining their own identity, have known the long series of empires that governed this territory from the Phoenicians to the French.

…Every Jewish community in North Africa formed a microcosm in which it was possible not only to observe at first hand an ancient heritage that had been faithfully preserved but also the rapid transition from a civilization based on the Arab Middle Ages to one that is part of twentieth century France or Israel… Thus, the history of mankind may often be summed up in the changes that have overtaken one community, one family, and one man.

–From Andre Choraqui,

Between East and West, The Jews of North Africa, 1969

The Zionist Of Sidi Bou Said

Felix wanted to show off his battle scars from the June 1967, Arab-Israeli War. He said he had fought in the Sinai and was proud to display the token of his brave service. The dark, wiry twenty-nine year old tugged at his custom tailored body shirt but found it no easy task to extract the shirttail from his equally formfitting bell-bottom blue jeans.

Fortunately, this technical delay deterred, him from exhibiting his wounds in a room full of Tunisia’s leading citizens at their latest, chic playground, La Baie des Singes Bowling Club. Compounding the boldness -of this attempted display was his claim to have fought not for the Arabs, but for Israel. Moreover, he was declaring his allegiance in modern Israeli Hebrew in a crowd of his fellow Tunisians, speaking their distinctive Tunisian dialect of Arabic, sprinkled heavily with French (?) expressions like “jouer au bowling a la Americaine.”

But Felix, the would-be Israeli soldier, did not get very far in Hebrew. And once his Hebrew broke down, the truth came out. He was more comfortable speaking Tunisian Arabic than Hebrew. But like most members of Tunisia’s Jewish upper bourgeoisie, who are educated in French schools in Tunisia and France, Felix preferred speaking French.

The battle scars, which he so hospitably offered to display to his female interviewer, were the product not of an Arab sharpshooter, but of a fertile imagination. His tale was a flight of fancy from an otherwise sad narrative of the death of the Tunisian Jewish community.

Anything Jewish interested Felix. Being Jewish, he was therefore very interested in talking about himself. His personal identity is inseparable from his ethnic identity. Felix thinks of himself first as a Jew and then as a Tunisian. His Jewish training was simultaneous with his schooling in French. And although he formally dropped religious school after his bar mitzvah, the die had been cast and his Jewish consciousness forged. He sees the inside of the Grand Synagogue on Rue de la Liberte (where Jewish life is centered) only twice a year – for

Yom Kippur and Passover. Yet he observes the two holidays proudly and conspicuously. Declining a meal offered him by a Muslim comrade during Passover week, Felix replied not with a simple “No, thank you,” but rather, “I can’t; it’s Passover, and I eat only special food.”

Close family ties in Tunisian society reinforce Felix’s religious convictions. “Each Friday night,” Felix fondly reminisced, “twenty-five people – counting my parents, my six brothers and sisters, aunts, and uncles – used to gather for the Sabbath meal.” Since the Tunisian Jewish exodus to France and Israel which began twenty years ago, only four people – Felix, his parents, and a little sister remain to observe the Sabbath.

His Jewishness determines his political predilections too. “If you’re a Jew, you must at least have a sentiment favoring Israel. Me. I’m a Zionist, and I don’t hesitate to argue politics with anyone. Everyone knows my views.”

Felix’s political remarks seem daring, no doubt, to persons familiar with most Arab countries where Jews – regardless of what they think – maintain either a self imposed or government-imposed silence.1 But Felix can afford to identify himself as a Zionist.

Scion of one of the wealthiest Jewish families in Tunis, which means one of the richest in Tunisia, he has been raised in a privileged, powerful, and relatively secure society. He is accustomed to the ultra-comfortable life of spacious, white mansions filled with servants. Strollers on Rue de la Liberte – Tunis’ prestige boulevard during the French Protectorate where resided colons, assorted European minorities, and wealthy, Europeanized, Tunisian Jews – can still see one of Felix’s uncle’s mansion with wedding cake architecture and formidable, wrought iron gates decorated with the family initials. (In 1956 at the end of the French Protectorate, an estimated one hundred percent of all shops on Rue de la Liberte were Jewish owned; today the estimate is five percent.)

In 1951 when Felix was ten years old, the Tunisian Jewish community was at its zenith – 105,000 individuals, sixty-one percent of whom were living in Tunis. There are only ten thousand left in all of Tunisia today according to a count made this month based on figures provided by each family purchasing matzah for Passover.

Avenue de la Liberty – traces of the past

Although the Jewish population in 1951 was a mere 3.23 percent of the entire Tunisian population, the importance of the Jews was disproportionately greater. Tunisia’s wealthiest industrialists, merchants, and export-importers – including members of Felix’s family – were Jews. Jews controlled an estimated seventy percent of all Tunisian commerce at one time. They were also over-represented in the liberal professions – doctors, lawyers, etc. – as well as among the intellectuals. And the Jew, M. Bessis, served as Minister of Public Health from September 1955, to April 1956.

The Jews, who were one-third of the non-Muslim Tunisian population, served as intermediaries between the colonizers and the local Muslim population. The French encouraged them to integrate into the colonized elite by granting them special privileges and easy access to French citizenship. Between 1911 and the end of the Protectorate in 1956, 7,311 Jews became French; these with their descendants eventually made up one-third of the Jewish population. (There were also Jews holding Italian and Maltese identity documents.)

During the struggle for Tunisian independence, the Jewish community was split in such a way that you could find militants against the French in the same family with Jews holding French citizenship. Some of Felix’s cousins are French citizens. But Felix’s Uncle Andre Barouch distinguished himself as a militant member of the Neo-Destour Party, Habib Bourguiba’s party of independence and ruling party to this very day. And, as such, Barouch had been exiled from Tunisia by the French.

About the time that Felix was bar mitzvahed and became a man in the eyes of his community, independent Tunisia came of age and took its place in the community of nations. That same year, 1956, Habib Bourguiba, Tunisia’s nationalist leader and benevolent dictator, appointed Felix’s uncle, Andre Barouch, a wealthy, fifty year old textile merchant, to the country’s first cabinet as minister of Reconstruction and Planning.

Barouch, whose name is a French pronunciation of the Hebrew word blessed (“Barouch is the first word in one of the most famous Jewish prayers, Baruch atah adonai …” Felix explained, intoning the Hebrew in a Tunisian accent characterized by nasal, flat A’s.),was included in the cabinet to reassure the Jewish community, whose skill and know-how were vitally needed at the time when the skilled French cadres fled the country. Barouch, however, did not survive the first reshuffle of the Tunisian government. In 1957, the gesture of having a Jew in the cabinet was abandoned.

Bourguiba’s gesture to demonstrate the liberal attitude of the new government, however, was so effective that today whenever the subject of Tunisian Jews is broached, educated Tunisians quickly bring up, like a Jack in the box, the example of the Jew in the cabinet. They talk as if Barouch were still sitting there fifteen years after his appointment and as if nothing has changed. But Barouch no longer even lives in Tunisia. And much has changed. Barouch is part of a steady stream of Jews immigrating to France and Israel over the past twenty-two years.

Why are the Jews – even former ministers – leaving? The answers differ for each individual, but the totality of responses makes up the obituary of the Tunisian Jewish community.

The exodus began in 1948 when the State of Israel was established and started attracting the poorer, Arabic speaking Jews who had practically nothing to lose by leaving and had the promise of something to gain in the “Promised land.”

Most French-speaking Jews, however, immigrated to France. In 1956, these relatively better off Jews, fearing their special privileges under the Bey and the French Protectorate would be revoked as Tunisia became independent, began to leave. Arabization goals in the independent Tunisian school system gave the Franchophone Jews an additional reason to leave. The Tunisian economic policy beginning in 1962 which socialized, nationalized and anesthetized the economy further encouraged emigration of Jews, who at one time had controlled approximately seventy percent of the commerce. Leaving for economic, not political reasons, many of these relatively well-to-do Jews have left their blocked funds in Tunisia and return each summer to vacation in Tunisia. Although Minister Ahmed Ben Salah, who was blamed for the policy, was thrown in jail in September 1969, and the government since June, 1970, has been trying to rouse the stagnated economy by pursuing a more economically liberal policy, the trend of Jews departing is irreversible. Too many people lost too much money. Too many lost confidence in economic prospects in Tunisia. And too many families already have members forging new futures in France and Israel. It is too late to return.

The economic reason—for leaving were accompanied by more spectacular considerations that had political overtones. In 1961 following the bloody, armed clashes between Tunisians and French troops in -Bizerte -France’s naval base and last military colonial bastion in Tunisia-there were nasty incidents against the Jews in the town of Ariana. This came about after a rumor circulated that the Jews of Bizerte had aided the French troops. In spite of government statements calling for order, the climate of insecurity was such that 15,000 left in the second half of 1961 and 10,000 in 1962. Following the French-Tunisian clashes at Bizerte, many schools of the French cultural mission were closed, diplomatic relations between Tunisia and the United Arab Republic were reestablished, and postal service with Israel was stopped, Jews took these three acts as further signals that it was time to go.

The first day of the June 1967 War, rioters wrecked Jewish shops, destroyed cars, and burned the Grand Synagogue on Avenue de la Liberte – as well as damaged the American and British Embassies. That summer, seven thousand Jews – many of them from the intelligensia – left Tunisia. And in January of this year, a rabbi was assassinated and two other Jews were injured in broad daylight on the streets of Tunis. (This incident, as well as government policy vis-a-vis the Jewish community, will be discussed further in another newsletter in this series.)

Yet despite all these factors – economic, political, psychological – ten thousand Jews remain in Tunisia. Why these people stay reveals almost as much about the position of the Jews in Tunisia as why the others have left. Felix is part of the remnant. He clings proudly to his minority status, which has not been unaffected by new political factors in the Middle East, specifically the establishment of the State of Israel and her poor relations with the Arab states. Felix’s minority status and accompanying political predilections has given him a unique distinction in Tunisia…

“FuFu is our Zionist of Sidi Bou Said,” MoMo, a friend of Felix, announced at a recent Saturday night couscous dinner party in Sidi Bou. Grinning approvingly, Felix accepted the label.

Commentary for the uninitiated: FuFu is Felix. MoMo is his Muslim chum, Muhammad. Couscous, a dish made from semolina, is to these Tunisians – regardless of religious taste – what spaghetti is to Italians. Sidi Bou Said is the world inhabited by Felix and Muhammad along with other intellectuals, artists, bon vivants, and assorted beautiful people, sporting Paris’ latest fashions as well as a wardrobe of fashionable nicknames like FuFu and MoMo plus CoCo for Claude, ZoZo for Hanina Stufa for Mustapha, and Alulu for Ali. And Sidi Bou is the “in” name for Sidi Bou Said. (To sum up, Stufa, FuFu, Alulu, MoMo, CoCo, and ZoZo eat couscous in Sidi Bou.)

More specifically, Sidi Bou is a sparkling white Arab village whose narrow, cobblestone streets and alleyways twist, turn, almost tumble down a mountain overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. Its traditional North African manzels (houses) with decorative ceramic tile walls and floors reveal nothing from the outside since all their walls facing the streets are windowless. Entrance through the imposing whitewashed walls is a set of thick wooden, blue, arched double doors decorated with black, wrought iron studs and doorknockers. Like the manzels themselves, no two doors in Sidi Bou seem to be alike. The fortress-like quality of the houses and relative inaccessibility of the village itself (a half-hour’s commute from Tunis) – not to speak of nature’s play of light and shadow on the never repetitious architecture – have made Sidi Bou Said all the more inviting prey to the invading chic of Tunis, who are changing Sidi Bou’s character from a traditional, Arab village to a Greenwich Village.

Felix spends all his abundant free time in Sidi Bou, but don’t bother looking for him in his airy, sunny apartment, which is part of a sub-divided manzel in Sidi Bou Said. He still lives with his parents in Tunis near Rue de la Liberte and often lends his bachelor’s pad to friends or friends of friends. “Sidi Bou is just one big family,” Felix is fond of saying.

The busy bachelor passes the evenings – and early mornings – at Sancho’s, his clique’s discotheque cum clubhouse (The doorman admits just a select few). Only occasionally, Felix will stay at home to tune in Kol Yisrael on short-wave radio.

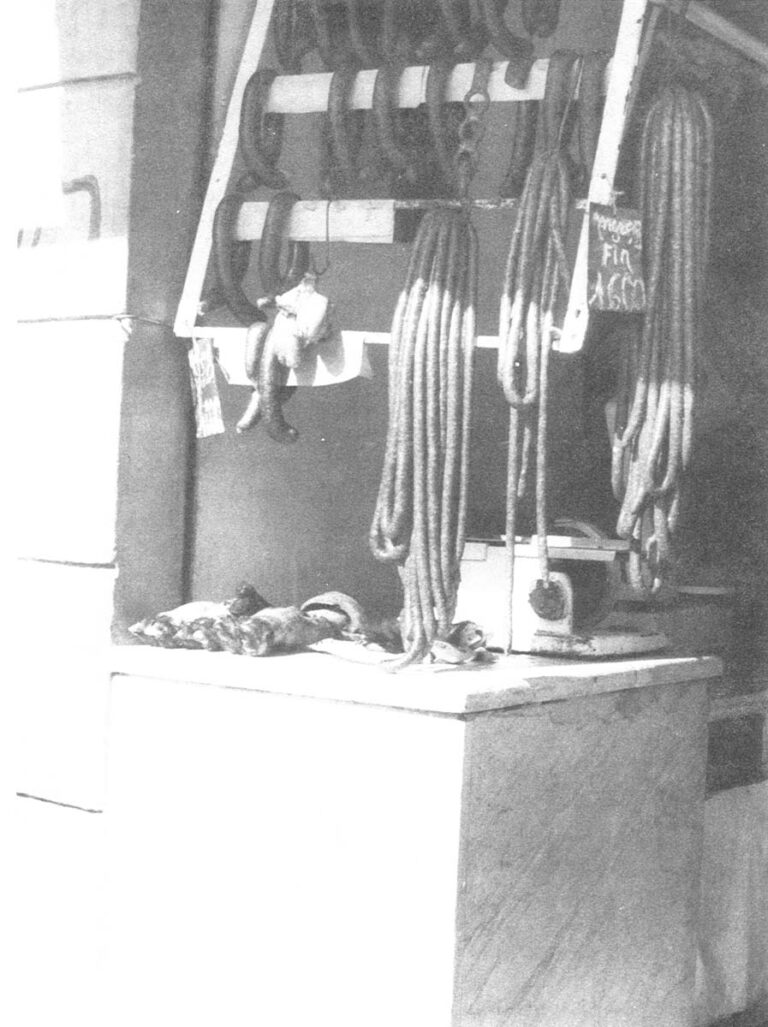

Saturday and Sunday afternoons, Felix is sure to be at the Cafe des Nattes, where the sun and action is nonstop until, of course, sunset when only the action is nonstop. Sidi Bou regulars flock to – and on the straw mats covering the famous steps of the cafe. They sip strong, sweet, mint tea garnished with pine nuts from tiny glasses and munch on toasted almonds and cookies sold by street vendors carrying big straw baskets. In affected boredom, they twiddle flowers hawked by peddlers and watch the tourists who come to watch them – just as the high-school set invade Harvard Square on Saturday afternoons, sit for a while along the banks of the Charles River or on the steps of Widener Library, lick Brigham’s ice cream cones with jimmies, and for a few, brief hours breath the rarefied air of Harvard University. (Police busts of Sidi Bou pot parties are likewise reminiscent of Harvard Square.)

Staking out a spot on the mats, diminutive Felix sweeps off his flowing, floor length, white burnose (a full length cape with hood which is Tunisia’s traditional garment far men and what the local chic of both sexes are affecting these days) and greets his friends. Hardly budging a facial muscle, he mumbles, “Oh, how are you, dear.” “Oh” is intoned with a slight rise in his voice to express surprise – but a very deliberately controlled, slight surprise. He automatically kisses his female friends on each cheek and settles down, finally, to soak up the rays.

“This is why,” Felix says, gesturing to encompass the picturebook scenery of Sidi Bou which so pleases postcard manufacturers and tour agents, “I’m going to Israel.” “Even though all my education in Tunisia has been French and even though I did my university studies in France, I can’t live in France. There’s no sun. But in Israel, there is the same sun and Mediterranean as here in Tunisia.”

“And when I go,” Felix asserted breathlessly – the chiseled features of his Semitic face finally becoming animated, “I’ll be an Israeli commando.”

But why, Felix, do you want to kill Arabs?

“Yes, if I have to. But noooo. No, I’m no racist, and that sounds racist. My best friends are my friends here in Tunis, and they are Arabs. We are like brothers.”

Felix’s remarks about his Arab friends sound cliched, but they are true nonetheless. They dine together, meet for coffee after lunch and dinner, go bowling, frequent the same discotheque, and bathe at the same beach club. Not bothered by Anglo-Saxon bans against members of the same sex touching each other, Felix lounging around a friend’s living room will lay his head in Kamal’s lap. Or he and Muhammad will romp on a bed giggling like two ten year-olds playing in a haystack.

His friends – some of whom are outspoken opponents of Zionism – are loyal to their “Zionist of Sidi Bou Said.” They explain away his political ideas this way: “You must understand that FuFu’s ideas are not at all political; nor are they very systematic. FuFu wants to be an Israeli, not a Zionist. He wants to go to Israel, but he doesn’t understand that in Israel, there are anti-Zionists just as in Germany there were people who weren’t Nazis.”

Felix’s friends sympathize with him in his dilemma. If you realize that FuFu is very attached in Tunisia. After all he has stayed this long. Yet he feels compelled to find his fate in Israel.

So, Felix has his friends in Tunisia. And he has his comfortable life in Sidi Bou Said and on Rue de la Liberte. And he has his money. As one of his cousins put it, “Felix’s only problem is that he has too much money.” He would have left by now for Israel like his two younger brothers. But his seventy-eight year old father is ill, and Felix, the eldest male of seven children, is responsible for the family’s industrial and commercial enterprises. His money – as well as all the other things in Tunisia which are too nice to give up – keep him in Tunisia where he is part of the remnant of the Jewish community.

If life is so good in Tunisia, why should Felix want to leave for Israel at all? His reasons for leaving are not so much economic – mixed with fear of violent, political developments – as in the cases of the bourgeoisie who moved to France or the Jewish proletariat who went to Israel. Economics and politics are important considerations for him, but up until now, neither was important enough to make him leave. Rather, his reason for wanting to go to Israel is more psychological.

His fate, Felix feels lies not in his birthplace, Tunisia, but in his ethnic homeland of Israel. There is no future for him in Tunisia, whereas in Israel, there is a possibility, he thinks, of a great existential experience. “If I have only one life, I want to dedicate my life to something greater than me.”

By going to Israel, Felix can fulfill the Zionist half of his identity as the Zionist of Sidi Bou Said. But, unfortunately, by so doing, he will have to forfeit the other half of his split personality – the Sidi Bou portion and what that stands for, his attachment to Tunisia.

Either way, Felix cannot really win as the Zionist of Sidi Bou Said. He has to give up one or the other loyalties. But the conflict and tension from this dilemma, which Felix mentions often, at least adds character to his face. And it provides an interesting topic when conversation runs dry – as it usually does – at the Bowling Club.

In last year’s annual report of the Joint Distribution Committee, the American welfare agency that aids needy Jews the world over, Samuel L. Haber, the agency’s executive vice chairman said that in the Arab countries, the agency is “shut out by a wall of silence and terror and it is difficult, if not impossible, to reach the ten thousand Jews trapped there.” He did not name the countries. The committee has been able to operate with little hindrance in Morocco, Tunisia, and Iran.

Another report provides this information on Jews in Arab lands:

- Libya – a few hundred Jews are left since the mass exodus in 1967 stemming from the riots at the time of the June War and since the Libyan coup, September 1969, which overthrew King Idriss.

- Egypt – 227 heads of family were in jail since June 1967, and 137 were released suddenly last year and with 260 dependents were allowed to leave. Less than 1000 Jews remain; 80 are still in jail.

- Iraq – 2,500 remain who at the end of 1969 were not allowed to leave.

- Syria – 4,000 Jews; many are still in jail for attempted border crossing into Turkey in 1965.

- Lebanon – 3,000 remain. They provide for their own needs. One thousand children are in parochial schools.

Tunisian government policy, which has been comparatively liberal, will be discussed in full in a later newsletter in this series.

By the end of the Protectorate in 1956, most Jews had moved out of the hara (ghetto) of Tunis into European quarters. In that year, the 7,638 Jews remaining made up only 66.3% of the quarter’s inhabitants. As early as the first part of the nineteenth century, Jews started leaving the hara for the French section of Tunis. The movement was led by the Jews from Livorno (Leghorn), who ever since their arrival in Tunisia in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries had constituted a class apart from the indigenous, oriental Jews. (Europeanized, bourgeois Jews were not then the product of French colonialist policy. According to the renowned historian of Tunis, Paul Sebag, “The Livornais, enriched by their trade and speculation, Europeanized by their origin and their customs, could mix only with difficulty with the mass of indigenous Jews, for the most part destitute and who, by their language, their costume, their habits belonged to that group of oriental people disparaged by the Westerners.”

Received in New York on June 8, 1971.

©1971 Paula Stern

Paula Stern, a free-lance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner. This article may be published with credit to Ms. Stern and the Alicia Patterson Fund.