Life is not all politics, war, or guerrilla fighting for a Palestinian living under Israeli military occupation. And today the majority of the world’s Palestinians find themselves under Israeli rule. Israeli statisticians figure there are 974,000 inhabitants of the West Bank of Jordan and the Gaza Strip occupied in the Six Day War, June, 1967, plus approximately 400, 000 Palestinian Arabs who have been Israeli citizens since Israeli independence in 1948 amounting to about one and one half million Palestinians. Officials count between two and one half and three million Palestinians in the world.

The Fatmi family is no different from most Arabs under Israeli occupation. Just as Israel’s rule is in general firm yet humane, the Fatmis combine a corpus of hostility toward Israel with a desire for peace. The Fatmis are from Ramallah (population 13,000) on the West Bank. When Ramallah citizens thought they could do something about the Israeli occupation in 1967 and 1968 the town was a center of opposition – strikes, demonstrations, and petitions. It was from Ramallah that the women left to plant explosives in the Israeli supermarket in Jerusalem, which killed two university students. And Ramallah Mayor Nadim Zarou was deported by the Israelis several years ago for incitement.

Today, however, most people have little hope of soon replacing the Israelis with anything better. They have little choice. Nasir is dead. The Palestinian guerrillas are a military and political disappointment. King Hussein is held responsible for thousands of Palestinian casualties (more than they suffered in the Six Day War) inflicted during last year’s civil war in Jordan. Other Arab regimes are making life difficult for the Palestinian Diaspora warning the Palestinians to drop politics to avoid repeating the Jordan insurrection. And among the Palestinians themselves, who bunch in rigid, clan groups harboring suspicion toward those outside the family, any likelihood of unified, Palestinian self-salvation in the near future is dim. The Palestinians under Israeli rule are demoralized. Lacking any alternative, they are coming to grips with the reality that they have little choice but to make the best of their situation – even under the Israelis.

Appreciating Israel’s might, desiring peace, and having no attractive alternative – guerrillas, Hussein, or Sadat – the Fatmi family is politically passive – no matter the sullen bitterness toward Israel it may harbor. Just by living each day and coping with the rules of military occupation, it is de facto peacefully cooperating with its enemy.

Mr. and Mrs. Fatmi describe their daily existence under occupation. They sit at the family dinner table which itself tells of peaceful interaction between Palestine and Israel. They have spread the table generously with West Bank fresh fruit, vegetables, and meat alongside Israeli canned and packaged foods. Mrs. Fatmi serves Israeli juices and soda for beverages. After the meal, Mr. Fatmi lights up a Farid cigarette, manufactured on the West Bank.

After lunch the group moves to the sun porch, a jungle of plants. The maid, who wears a traditional long, black Palestinian dress with colorful, hand -embroidered bodice serves Turkish coffee. The impression a visitor soon gets is that despite a multitude of changes wrought by a peaceful yet military occupation, old ways and habitual attitudes manage to persist.

Both Mr. and Mrs. Fatmi come from wealthy, influential backgrounds. While their families hold traditionally powerful positions in the community, the Fatmis’ style of life is considered very modern. Their home is one of the finest in Ramallah, which is known for its fine villas where before the 1967 war many oil rich Arabs from the hot desert of the Arab Gulf spent relatively cooler summers. (In spite of Ramallah’s reputation as a modern resort town and the fact that for example the comfortable Fatmi home has a bidet douche imported from France in the bathroom, the Israelis discovered that even running water was a luxury in Ramallah. In 1967 three-quarters of Ramallah’s homes were without running water and four-fifths had no modern sanitation system.)

Mrs. Fatmi is not a traditional upper class Arab woman spending all her time in the house or in some cases even wearing a veil. The mother of three, Mrs. Fatmi teaches in one of the twenty-two schools in Ramallah, which has a large Christian population and a reputation as a progressive, intellectual center in Palestine. (However, mixed classes – boys and girls in the same classroom – are still unacceptable in this, one of Palestine’s most modern, towns.)

Mrs. Fatmi is a dark, handsome woman who physically towers over her husband. Mr. Fatmi, who like the rest of the family – and many other West Bankers – speaks perfect English, talks about his holding a government post under the British Mandate, then – from 1949 – the Jordanians, and today the Israelis. He reports that the Israeli government has given the West Bank local politicians – mayors, sheiks, and mukhtars – more power in their localities by compressing and decentralizing the bureaucratic hierarchy existing under the former Jordanian regime.

It seems strange for Mr. Fatmi to be working under the Jews. It has been almost twenty years since he last had contact with them – and then the Arabs and Jews were both subordinate to the British. The Mandate had drawn heavily (as has more recently the United Nations Relief and Works Agency) on manpower from Ramallah, reputedly a center of Palestinian elite. When Britain dissolved the Mandate, the United Nations partitioned Palestine, the State of Israel declared independence, and the Arab-Israeli War began, Mr. Fatmi moved his family to Ramallah from their home in Katamon, which after the 1949 division of Jerusalem became a quarter of Jewish Jerusalem.

Mrs. Fatmi explained, “We had been told to leave for fifteen days and that was twenty-three years ago. ” They revisited their home after the 1967 War. Although there were reports of Palestinians trying to reclaim their homes, they say they did not. They even describe favorably the industrial progress that Israelis have brought to what was once the Fatmi’s orange groves.

With genuine joy, they tell about visiting Jewish friends who they had not seen for decades. And, of course, they reestablished contact-including some marriages – with Arabs left behind in 1948 in what became Israeli territory.

Since the 1967 occupation, the Fatmis have kept their teaching and civil service posts. Like the other eight thousand five hundred public servants – including five thousand teachers – on the West Bank, they are paid by the Israeli Military government for services rendered. And until several months ago, they and their fellow public servants enjoyed a second salary from the Jordanian government. The Jordan-paid “resistance money” was an attempt to encourage loyalty to the Hashemite crown despite Israeli occupation. The Israelis had not interfered with Jordan’s efforts to buy loyalty. It seems that the effect of double salaries makes the West Bank population more prosperous and passive. Perceiving two authorities claiming allegiance (to Jordan) or cooperation (with Israel) probably leaves the population with no single political rallying point. As far as Israeli officials are concerned, this is desirable; the less unity in the West Bank, the less potential for unified opposition.

The Fatmis do not talk about their double income. They spend more words deploring rising prices in the West Bank as a result of the economy being tied to Israel and her inflation. Like most upper-class Palestinians whatever their profession – public servant, merchant, or industrialist – they are also landowners. So, for example, they complain about rising wages for farmhands. The farmhands’ wages have indeed risen ten to fifteen percent a year since the 1967 occupation. But farmhands still earn much less than if they left the Fatmis and – like one quarter of the West Bank labor force today, about thirty-five thousand men – commuted daily across the Green Line to jobs in Israel. “Wages earned in Israel by West Bank residents were about 70 percent above those in the areas; in the Gaza Strip the difference was higher – 110 percent, ” according to the Bank of Israel’s report, “The Economy of the Administered Areas 1970.”

The Fatmis may be bothered psychologically as the social and economic gap between them and the higher paid laboring class narrows-if even slightly. But they are not suffering economically. Although Israel’s social democratic ideology might favor leveling class differences in the occupied territories, the government is realistic enough to avoid disturbing the Arab territories’ traditional social stability that is based on a rigid class hierarchy. Realizing that the public servant is a member of the white-collar elite – the most articulate powerful group under occupation – the Israelis recently raised public servants’ salaries for the fourth time to keep up with rising prices. They did this in spite of funds from King Hussein unofficially reaching the West Bank.

Another indicator of prosperity is that the Fatmis recently moved into their new villa constructed since the Six Day War by a Palestinian emigrant to America. The Fatmis also continue providing the best in material comfort and education for their three daughters ranging in age from twenty to twenty-eight years. All three girls are college -educated, and all three dress in Paris’ latest fashions picked up on shopping sprees in cosmopolitan Roirut.

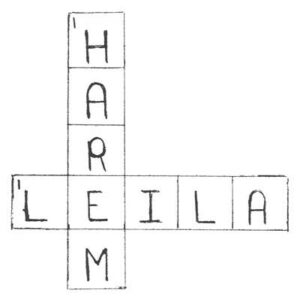

This summer Leila, the eldest, arrived at Lod International Airport, Israel, from Texas where she and her husband, also a Palestinian, have been studying. Along with approximately two hundred thousand Palestinians, one-fifth of the pre-War West Bank population, she left the area after 1967 without arranging to keep a permanent resident’s status and lost her residence rights. She was able to visit her family only between June fifteenth and September fifteenth as one of the one hundred and seven thousand summer visitors (Arabs) exercising the privilege to come to the administered territories (and Israel) if they have family still living there who would arrange the permit.

Israel’s summer visitors scheme had several objectives. It attempted to neutralize propaganda against Israel and let Arabs see Israeli life first-hand. (The number of visitors this summer represented about one-tenth of the Palestinian Diaspora estimated by Israeli officials to be one million people.) The program is also part of an Israeli effort to maintain the foremost link between Israel and the Arab world via the important economic and familial connections between the West and East Banks of Jordan and from there, the rest of the Arab World.

Leila had to leave the West Bank by September fifteenth. Although she and many other West Bankers who fled the land after the Six Days War and returned temporarily this summer have applied to regain their resident’s status, the Military Government has reportedly granted only three hundred requests-mostly from people in the liberal professions and some from students soon to complete studies abroad. Israel’s official position is that any permanent arrangement for refugees will have to wait for a final peace settlement.

In the meantime, Leila and her husband are in Kuwait where he practices medicine. For generations hundreds of thousands of Palestinians have left their homes for greener pastures abroad especially in the oil-rich Arab states. They send back money to support families remaining in Palestine. The Arab states benefit from the expertise of the Palestinians who claim to be the most educated and sophisticated group in the Arab World. Recently, however, the welcome from the Arab states, fearing the Palestinian population might repeat the insurrection, which occurred in Jordan, has cooled. These states are making it clear that they do not appreciate Palestinian political activity. Jobs are becoming scarcer for this group. In Saudi Arabia, for example, Egyptians are reportedly replacing Palestinians. And Palestinian students are experiencing discriminatory quotas against them in the Arab universities where because of the students’ merit they previously had been disproportionately represented.

“People believe that the more education we get, the more radical we become, ” explained the second Fatmi daughter, a soft-spoken but strong willed twenty-four year old beauty. Aida trains teachers for the West Bank school system, which as a matter of Israel’s “normalization” policy operates much as it did before the war. She did not leave home like Leila. Nevertheless, she must often deal with the military authorities for various permits. For example, she wanted to take her sisters on a weekend beach trip. West Bankers, who had been landlocked for nineteen years from 1948 to 1967 love bathing at the Israeli beaches, particularly – and ironically – at nearby

Herzliya (named for the founder of Zionism, Theodore Herzl). In order to go, she first had to receive permission to take into Israel her automobile which bears Israeli license plates with the Hebrew letter for “R” referring to Ramallah. And in order to spend the night in Israel, she needed another permit. She received the first but not the second, so rather than go for one day, she cancelled her hotel reservation and stayed home.

Her younger sister, twenty year old Qamar, is a college student and mother of a year old daughter. Each year since occupation she has renewed her one-year military government permit to leave the West Bank to study at Beirut’s College for Women. For the first time last summer, she was able to bring her husband home with her on the summer visitors program.

“All I knew about Israel was what people had told me or what I had read, “Qamar’s husband, Bassam, explained. He was anxious to see Israel with his own eyes. He is Palestinian from Ramle, a town in Israeli territory since 1948. His family left Ramle when he was three years old. The summer visitors scheme allowed him to visit his birthplace – and all of Israel – for the first time.

“I try to look at Israel objectively. Before coming, I had known and was impressed by the Israeli accomplishment – how they built a culture from nothing. But I came as a Palestinian too, and I cannot always separate my emotions from my desire to be objective. Basically I came to Israel for a new experience, ” said the fervent young man in his most flowery, academic speech. He is proud of his B.A. degree from the American University at Beirut. He wears an American sports jacket and tie on most occasions-although many Palestinian men have adapted to occupation by dressing in the casual Israeli fashion.

The young man was surprised that he had so little contact with the Israeli authorities during his visit. “Since in Lebanon, I have always been discriminated against because I am Palestinian – I cannot find a job there, for example, ” he thought it only logical that his people’s enemy, the State of Israel, should give him even more trouble. But authorities checked his papers when he entered over the Jordan River bridge from the East Bank. After that he visited Israel’s cities and even kibbutzim and circulated around the West Bank talking politics. He was stopped only once, and that was for an identification check in Hebron, a major West Bank town, on a day of terrorist activities.

The boy stuffed his notebook with words of Palestinian notables he visited. They spoke in classical Arabic, the language of the educated class reserved for elevated conservations on matters such as politics and religion. Some talked of returning the West Bank to King Hussein. A few spoke of staying with the Israelis or at least keeping the economic borders with Israel open. Some expressed support for the Palestinian guerrillas.

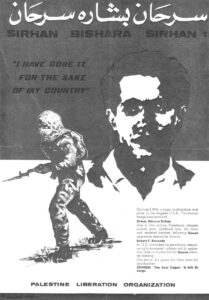

“It’s only natural for a Palestinian to resist Israeli occupation, ” the university student stated matter-of-factly while dining with friends in an Israeli restaurant built since the war by religious Israeli settlers to Arab Hebron. (Bassam prefers Israeli restaurants since he said they are more “sanitary” and he can also practice his elementary Hebrew.) Like many West Bankers, he vacillates on which political form he thinks the West Bank should ideally take. He seems to favor West Bank political independence under a “younger, more democratic” Palestinian leadership. Not Israel. Not Hussein. Not Arafat (of Fatah) or Habash (of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine.) And not the West Bank’s present traditional, self-appointed – sometimes ratified by elections – mayors and sheiks who for the most part cooperate with Israel as they had cooperated with Hussein and his grandfather, King Abdullah. “These men handed Abdullah the West Bank on a tray of silver at the Jericho Conference in 1949. They pocketed plenty in return while the Palestinians lost what they had not already lost to the Israelis in 1948.”

Bassam was impressed by the Israelis’ knowledge of the Arabs. “We Arabs have talked so much about Israel, but we know nothing about it. ” He is considering returning to Israel next year to pursue Israeli studies at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Neither Bassam who wants to learn more about Israel nor his family who would like to forget that Israel even exists will ever really like Israel. They resent being under Israeli occupation. “Hell under an Arab tyrant is better than heaven under the Jews, ” is an oft-repeated sentiment. And they consider the permits and military checks made in the name of security noisome and insulting.

Bassam and his family naturally side with his aunt in Hebron who claims the Israeli authorities have arbitrarily cut off her husband’s license to go to the West Bank to collect Jordanian pension payments. And they implicitly believe their cousin from Akko, an Arab town in Israeli territory since 1948, who claims to be permanently injured by Israeli torturers.

Optimistic Israeli officials would like to think that through daily, personal contact with Israelis the Arabs’ become more open to compromise with their enemy. Insofar as this happens, Israel’s iron fist in a velvet glove treatment lays, as an official put is, “a groundwork for an eventual formal peace settlement worth more than just the paper it is written on. “

But for the Fatmi family under military occupation, Israel’s vision of peace is not so easy to adopt. Mrs. Fatmi, who like most Arabs is a gracious hostess, concluded her family luncheon chat of Israel’s liberal civilian policy. She finally blurted out what she really felt. “The Israelis can afford to be generous. After all, they are sitting in our homes, which they stole from us in 1948.”

Received in New York on April 4, 1972.

©1972 Paula Stern

Paula Stern, a free-lance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner. This article may be published with credit to Ms. Stern and the Alicia Patterson Fund.