April, 1971

“I could speak in English, but since I’m at the American University of Beirut, I’ll speak in Arabic,” declared Leila Khaled, the intense Palestinian skyjacker. She had returned this year to the University, where she had studied pharmacy, to speak at one of the weekly campus bull sessions. She went on to denounce – among other things – American imperialism.

The American University of Beirut (AUB) – like a lightning rod in a thunderstorm – attracts criticism of United States presence in the turbulent Arab World. The criticism links United States official policies with the ostensibly private, American institution.

Samual B. Kirkwood, President of AUB, retorts, “When the University is accused of being a tool of American imperialism, my answer is, ‘Well, if that is so, four thousand people want to come here.'” Some say it is cultural imperialism. Call it what you will, but the fact remains that American influence on this year’s student body of four thousand – plus 14,603 others educated at AUB since its foundation in 1866 – has permeated to a profound, even psychological, level. Even the University’s critics reflect American influence.

Surrounding the campus, Ras Beirut, Beirut’s bustling commercial and entertainment center with neon flashing America’s favorites from hamburgers to basketballs, looks like the fifty-first State in the Union. And on the campus itself, the scene looks like any number of small, co-ed universities in the United States:

This year’s first issue of Outlook, the student newspaper written in English, reports the selection of Campus Beauty Queen, blonde Irene Shebabee “of Palestine.” Her alternate, who was pictured wearing slacks and. a tie-dyed T-shirt, is Bahreini Huda Sa’i.

On the ninth floor of the new AUB hospital (accredited by the American Medical Association), a handsome Lebanese intern, dressed in white, questions his American patient on living conditions, salary levels, etc. at the University of Rochester where he has been selected to do his residency. (Since AUB was chartered in the State of New York, its degree is recognized as the equivalent of any granted by a New York State University.)

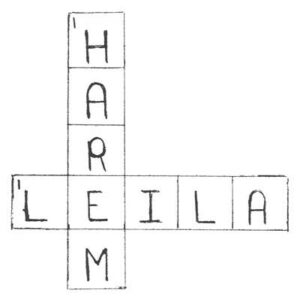

A hen party is in session at the modern Beirut apartment shared by coeds from Bahrein, Syria, South Lebanon, and Iraq. Sipping Turkish coffee and munching on Lebanon’s delicious fruits, they discuss what is on their minds. One girl worries about the same thing that might be bothering a college senior in the United States: meeting filing time for application to Columbia University Graduate School’s Philosophy Department; finding one of the rare attractive jobs for a female graduate; or marriage. Her lyrical eyes belie the tension in her voice as she discusses her role as an educated female in the Arab World! “A conservative culture gives us security. It’s difficult to branch out on our own. So we repress our conflicts and sublimate.”

It is perfectly natural for her to speak this American, quasi-Freudian “sociologise” with an Arabic accent. She conducts mundane affairs – making appointments, for example – in Arabic. But she slips into English rather than translate into Arabic usually more abstract thoughts originating in English’. In the middle of a conversation in Arabic, English, will be employed like shorthand; and comrades in the community of the American-educated will automatically understand this babel of Arabish (Arabic and English.)

Obits not only speak English; they speak the same language as Americans. In other words, they are in the same universe as Americans, sharing their values, status symbols, aspirations, and expectations.

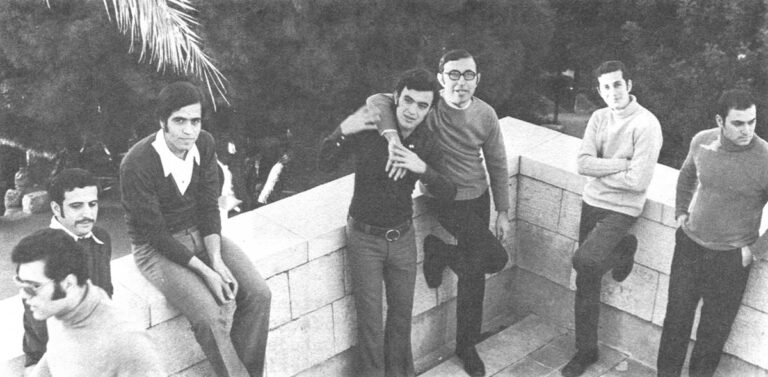

They do not simply dress a la American – midis slit to mid-thigh and shiny, leather boots stretching to the knee or – for the men – American Levi blue jeans and tennis shoes or Italian skin-tight ensembles. Their fashions symbolize a comprehensive change in mentality, especially when today’s student is compared with the first generation of AUBites. The men in the early days had to hike up their long dress-like gowns to play American sports. And the first Muslim female student, whose husband enrolled as a special student to escort her to lectures, wore two veils.

AUBites do more than flock to American movies like Woodstock and memorize the words to rock songs; that happens everywhere in the world. The students at AUB spend at least four years studying an American curriculum. Americana penetrates to a deeper, intellectual level.

They assimilate in four years more than just book learning. They also catch the spirit of freethinking and critical thought, which AUB’s President Kirkwood claims, is American education’s major contribution to the Arab World. “The student is urged to think for himself…. [we tell the student] don’t repeat by rote.” (Actually, this so-called free-thinking approach which is often contrasted with the French style of education and which Kirkwood contrasts with the “Eastern” approach, seems not to be an American invention, but rather a product of the times. “Too much of the teaching was either in the form of very deliberate lectures, which the students tried to copy down and learn by heart, or else recitations,” complained Bayard Dodge, who was appointed President of AUB back in 1923.)

AUB’s cultural contribution to the Arab World – whether it is dubbed “influence” or “cultural imperialism” – must be placed in perspective. An AUBite is not an American, no matter how Americanized he is. He is still very much an Arab, no matter how much he differs from earlier generations or even from other Arabs in his society today.

Furthermore, AUB cannot take all the credit – or blame for Westernization in the Arab World. The Nationalist Movement in the Arab World in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which encouraged adoption of “modern” ideas from Europe, was a crucial factor. The Nationalists, writing from Beirut and Cairo, performed the essential task of adopting “alien” ideas to their traditional, home environment and translating them to fit the needs of their people.

Actually, the Nationalists’ accomplishments dovetail with the achievements of the American University of Beirut, for the University has historically been involved in political developments in the Middle East. As with the University’s cultural role in the Arab World, the University’s political role may be dubbed “influential” or “imperialistic,” depending one one’s political predilections.

The one hundred and five year old school has been educating Arabs even before they called themselves Arabs; AUB’s foundation date precedes the Nationalist Movement, which is responsible for stretching the term “arab” from its restricted meaning of “bedouin” and applying it to all Arabic-speaking people. In the book, The Arab Awakening, historian of the Nationalist Movement George Antonius writes, “When account is taken of its contribution to the diffusion of knowledge, of the impetus it gave to literature and science, of the achievements of its graduates, it may justly be said that its [AUB’s] influence on the Arab revival, at any rate in its earlier stage, was greater than that of any other institution.”

AUB alumni were the vanguard in every stage of the Nationalist Movement. In the last years of the British and French Mandates in the Middle East, the book Arab Consciousness and Nationalism by Constantine Zurayk Professor of History of AUB and onetime acting President, was read clandestinely in schools throughout the Arab World. In the Forties when the first Arab nations were gaining sovereignty and seats in the United Nations, five AUBites signed the United Nations Charter and nineteen alumni attended the first General Assembly of the United Nations.

These early generations of AUBites were exceptional in the Arab World. They could afford a Western education – or any education for that matter. They were mostly “aristocrats,” according to Dr. Yusuf Ibish, Professor of Political Science at AUB and himself a member of a prominent Damascene family. When he attended the University, “AUB then was for those who could pay. AUB was a rich man’s college. The display of wealth was different. Few of us had tasteful consumption and honorific waste…. AUB did a beautiful job alienating me from my society. I was raised in a jar…. Going to live in a Syrian village for three years was a cultural shock much more than going to America, even though the Americans eat in drugstores and have their boots shined in barber shops.”

Today’s AUB student is still a privileged member of his society. But AUB is making a significant effort to close the gap between those who can qualify for entrance and those who can pay for an education. Some students still pay the tuition of between $550 and $850, but their number is decreasing. An estimated six hundred to seven hundred students are fully supported by the University, international organizations, or some government funds. Fifty-six percent of the students receive some kind of financial aid. In Ibish’s words, these “qualified students… usually come from ordinary people.” He specifically mentioned children of Palestinian refugees.

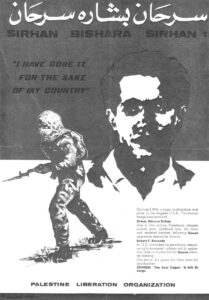

The broader socio-economic composition of the student body complements the political preoccupation on campus this year. This September, the multiple hijackings by Palestinian guerrillas made celebrities of a revolutionary breed of AUBites – including Leila Khaled (who only attended AUB for one year); Dr. George Habash, Chief of the Marxist Maoist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, a graduate of the Schools of Arts and Sciences and of Medicine; and Dr. Wadia Haddad, a graduate of the Medical School and reportedly mastermind of the hijackings.

The Palestine problem has gripped the AUB campus since 1947, according to President Kirkwood. But since the June 1967 War, the rise of the commando movement, and the radicalization of segments of the movement, the political temperature on campus keeps rising.

“The Palestine Liberation Movement is the first real mass movement in the Middle East. It is the first time that the lowest class is involved. It has changed all Arabs from a spirit of total dejection after 1967 to a fighting spirit,” asserted an AUB senior to his buddies one afternoon after classes. He is the son of a Bahraini millionaire, so he cannot really speak for the masses. But he sincerely believes that he, along with many of his fellow students, have been “radicalized” by the Palestine Liberation Movement.

Sitting in Uncle Sam’s coffeehouse where patrons can damn Yankee imperialism over a cup of ‘ahwe americani (American coffee), his appearance matched his new political posture – self-consciously new New Left. (Whether chic or “radical chic” perfectly groomed or perfectly messy, the AUB student is conscious of his appearance.) His hair – masses of black curls – and moustache were bushy and untrimmed. He needed a shave. To offset his trop bourgeois nylon windbreaker and yellow and black flowered body shirt, he wore what he called a “fedayeen belt.”

Him comrades mocked him and said the belt was probably Lebanese army surplus. But his friends especially the self-styled Iraqi hippie in full beard, who harangued on the joys of marijuana, begged for his meals, and bragged of his uncles – one a founder of the Iraqi Communist Party and another an early Iraqi anarchist – cheered the son of a millionaire from Bahrain, where “they say Communists are men who sleep with their sisters,” for his excellent Marxist analysis of the Palestine problem.

The Palestine issue, however, is not just a novel issue for an excited youth. For more than two decades, many of the school’s most prominent faculty members have worked to change the status of the Palestine people and the State of Israel. And since 1967, their activities have multiplied. Professor Yusef Sayegh of the Department of Economics is Director of the Center for Planning, of the Palestine Liberation Organization. He and Professors Halim Barrakat and Peter Dodd of the Department of Sociology have published studies on the Palestine question for the Palestine Research Center and/or the Institute for Palestine Studies. Serving the Board of the Institute for Palestine Studies is Professor Emeritus and one time Acting President of AUB Constantine Zurayk.

The Americans on campus – professors and students – also are preoccupied with Palestine. After six weeks at AUB, Rick Wellons, one of the thirty-three American Junior-Year-Abroad students on campus, reported that “in an position here [at AUB] as Americans immersed in a political situation where United States government policies are directly involved, none of us can help but have an expanded political consciousness forced on us…. Our United States government’s involvement is too deep for passivity.”

Passive, they are not. Some students who have spent their school vacations in refugee/commando camps have returned inspired to organize support for the Palestine cause on campuses back in the United States. Last year, the American students greeted Assistant Secretary of State Joseph Sisco with “Sisco go home” signs and pelted the United States Embassy with rocks. A number of American professors including Professor David ‘Gordon have formed a pressure group called Americans for Justice in the Middle East aimed at the American public and its leaders.

Wellons reported in the school newspaper Outlook that the AUB administration has warned the American students to restrain their activities. “Only two days after the opening of this academic year an incident occurred at the first student Speaker’s Corner when an American delivered an impromptu speech that aroused the indignation of AU-b President Kirkwood himself, provoking him to order an immediate investigation of the incident and a stern reprimand to the American speaker. On the same occasion another American AUB student who spoke was called into the office of Dean Najemy to be personally reprimanded.”

The school administration is clearly concerned about what it considers its bad press in America, particularly an NBG documentary in the fall and an article in the October 5, 1970; Newsweek entitled “Guerrilla U.” The American University of Beirut depends on American goodwill and dollars.

Kirkwood has a dilemma, for he also realizes the popularity of the Palestine cause on campus and – as a corollary almost – the unpopularity of the United States’ policy in the Arab-Israeli conflict. “Ten thousand people in a University community (with dependents) are going to be effected by the environment around it…. And since 1967, the response to Palestine has been more acute.”

“In the past,” he related, “activity came after graduation and political activity was severely proscribed; this was essential, for the University has been host to an impressive number of religious sects and nationalities, each with its own political loves and hates.” (The Armenians, for example, last year had an anti-Turk campaign.)

Kirkwood observed that as on any campus in the United States, “some [of the students] will grow up to be rabid revolutionaries; others will be solid, conservative individuals.” His policy regarding political activity is: “Our faculty and students as individuals are perfectly free to think as they wish, but they can’t say this is University policy.”

Actually, by American student standards, the campus is rather tame. The son of the Bahreini millionaire will no doubt return to Bahrein when he graduates this June.

At a Balfour Day Rally, which is annually held on campus to protest the Balfour Declaration, Palestinian Professor Hisham Sharabi, on leave this year from Georgetown University, spoke to the students about their political commitments. “Great expectations are set upon you; you know that these expectations are not justified. You, as members of the intelligentsia, are not members of the revolution. The fate of the revolution does not depend upon you.” The students were startled by the truth, which Sharabi spoke. “By the training to which you are exposed [at AUB], you are being groomed to join a small minority in the Arab society and to abandon the masses which form your people – the 85% or 90% that go to bed hungry…. Members of the revolutionary elite engaged in revolutionary activity must abandon what you are.”

Professor Yusef Ibish, in a lighter vein, summed up the general character of his students. “It’s a bovine student body. You can tell by how they come to class – in their latest fashions. The clashing, very expensive perfume not subtly used would split one’s head. One girl repeatedly came late to my class; she explained it was because her coiffure does not open on time and he combs her hair daily.”

AUB may not be facing an immediate political crisis, but it is very definitely caught in an identity crisis. Mounting criticism of United States policy in the Middle East and particularly vis a vis the Arab-Israeli conflict provokes the inevitable question: how American is the American University of Beirut?

Americans make the decisions. They hold the top administrative posts. And there are more than three times as many Americans as locals on the Board of Trustees, including executives from America’s largest economic interests in the Middle East: Texaco, Standard Oil, American Tool and Machine Company, First National City Bank, Morgan Guaranty Trust Company, Chemical Bank. American oil companies are among the University’s largest donors: Aramco, Caltex, Mobil, Richfield, Shell, Standard Oil (California), Standard Oil (New Jersey), Tapline, and Texaco. In addition, the Ford Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation are big contributors.

“American money has made the University what it is today,” declared an official of the Agency for International Development (AID), which provides the lion’s share of the school’s assets. Director of Development Arthur Whitman estimates that this year AUB’s United States government funds amount to between $6 and $8 million. Between forty and fifty percent of the school’s operating budget comes from USAID educational grants which come under section 214 of the Foreign Assistance bill – Aid to American Schools and Hospitals Abroad. (Roberts College in Turkey, The American University in Cairo, The American Farm School in Greece, and several institutions in Israel also receive funds from this source.)

AID has also paid over the years for specific capital projects like AUB’s technological wonderland, the 630 million Medical Center. And AID channels funds in a contractual arrangement whereby AUB takes AID selected students – 517 this year – from the Middle East and Africa and AID pays for the entire cost – not just tuition – of educating them. So, for example, if ten percent of the Agricultural School students are AID-selected, AID supports ten percent of the Agricultural School.

Both AID and AUB are pleased with the foreign aid arrangement. As one AID official said, 11AU3 is an example of something we The United States government would have built otherwise, and AUB is ten times better an example of a University than any we have ever built under an aid program.” It is helping to educate badly needed cadres in the area with no brain drain. Educating students at AUB avoids the attrition problem, which occurs when students are brought to the United States. And the cost of education in direct expenses is less than if the student was brought to America.

University connections with the United States government, however, have put AUB in embarrassing positions. Just this year, the University exhausted the last penny from an Army Advanced Research Program which caused a big stink on campus. In Professor Yusef Ibish’s words, “There is a creepy feeling in Beirut that AUB is not a purely academic institution. I don’t know. They had no business taking AARP money.”

But claims that AUB is an extension of United States politics in the Middle East are exaggerated. As one United States Embassy official in Beirut expressed it: “The school was here and operating almost before we had a State Department and almost before we had a consulate here and long before we had foreign assistance. Government subsidy is a late-blooming idea. The physical plant, philosophy of the place, tone was there…. It is an American university, but it is just as private and independent as it can be except for the one tie point in operating costs. Yet that is so detached that the tie [between the United States government and the school] takes place in Washington.”

Nabil Ashkar, in the Office of Alumni Affairs, also sought to explode the claim that American imperialism – political or cultural – exists at AUB. Himself a Lebanese graduate of AUB, Mr. Ashkar said in an uncanny American accent, “We’ve had more diehard nationalists to have graduated from here than any university.”

Received in New York on April 21, 1971.

©1971 Paula Stern

Paula Stern, a free-lance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner. This article may be published with credit to Ms. Stern and the Alicia Patterson Fund.