June, 1971

“Our revolution is a drop of blood, a drop of sweat, and a drop of ink” asserts a Fateh poster. So it should not be surprising that Palestinian artists dabble in politics. The best-known Palestinian artist, Ismail Shammout, for example, speaks of his art work in political terms, “I’m happy that a landscape of a refugee camp or a tragic theme is hung in the house of rich people because I do make people remember.”

Palestinian studio art was not born from the Palestinian Liberation Movement. But the June War and the rise of the commando movement re-sensitized Palestinians who are expressing their national identity by painting as well as skyjacking.

Poster art is most obvious. In Beirut, cultural capital of displaced Palestinians, the Fifth of June Society – it’s name and founding date demonstrate the impact on Palestinian self-consciousness of the Arab-Israeli War which started June 5, 1967 – raises funds by selling poster size reproductions of works of Arab artists that appeal to the more sophisticated taste of wealthy patrons and the Western educated.

The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), the group responsible for last September’s epidemic of sky-jackings, produces earthier specimens for recruiting posters in refugee camps. One “Uncle Sam Wants You.” appeal with an oriental twist is pitched to the family, the basis of Arab society. A determined commando poses clutching his gun; in the background his parents stand near a refugee camp; and behind that is a barbed wire enclosed village. The caption reads: “THIS IS OUR SON. WHERE IS YOURS?”

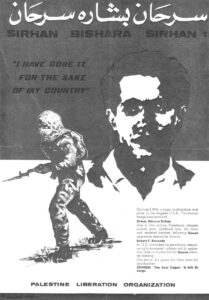

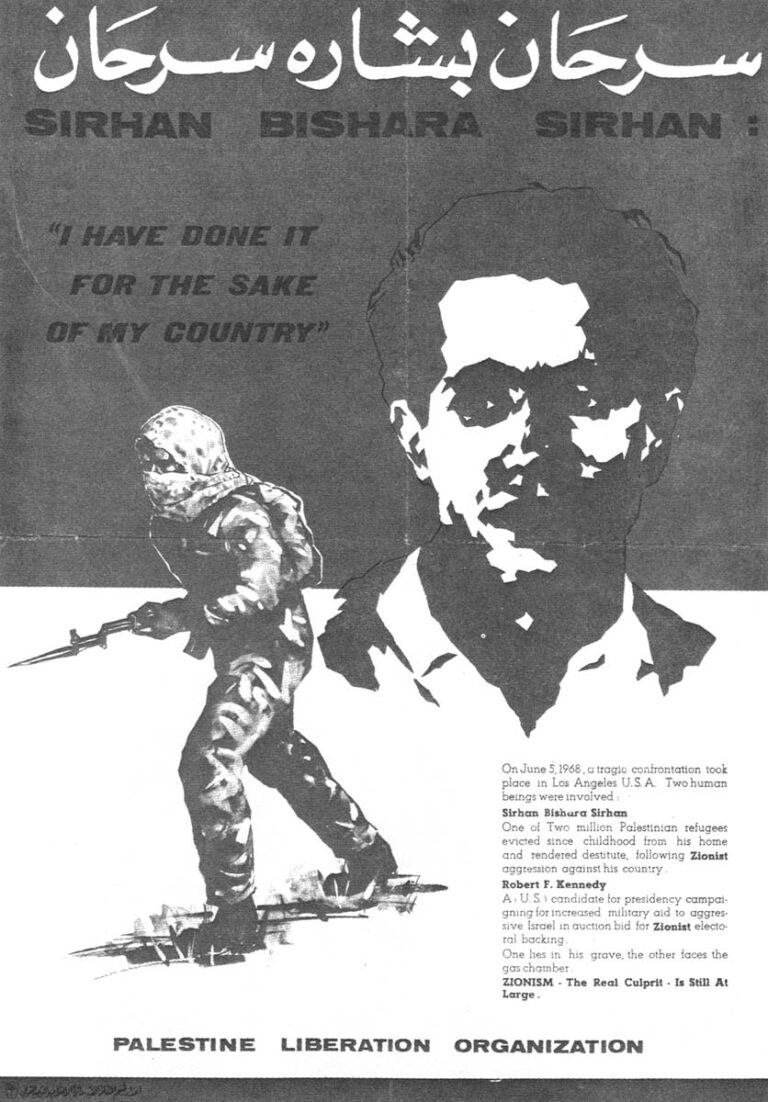

Another poster circulated in several languages by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO, theoretically the central authority for all commando groups) portrays Sirhan Sirhan as folk-hero. Next to a gun-wielding fedayee(commando; the literal translation from Arabic is “one who sacrifices) are Sirhan’s portrait and his words, “I have done it for the sake of my country.” The message on the poster reads:

On June 5, 1968, a tragic confrontation took place in Los Angeles U.S.A. Two human beings were involved:

Sirhan Bishara Sirhan

One of two million Palestinian refugees evicted since childhood from his home and rendered destitute, following Zionist aggression against his country.Robert F. Kennedy

A (U.S.) candidate for presidency (sic) campaigning for increased military aid to aggressive Israel in auction bid for Zionist electoral backing. One lies in his grave; the other faces the gas chamber.Zionism – The Real Culprit – Is Still At Large.

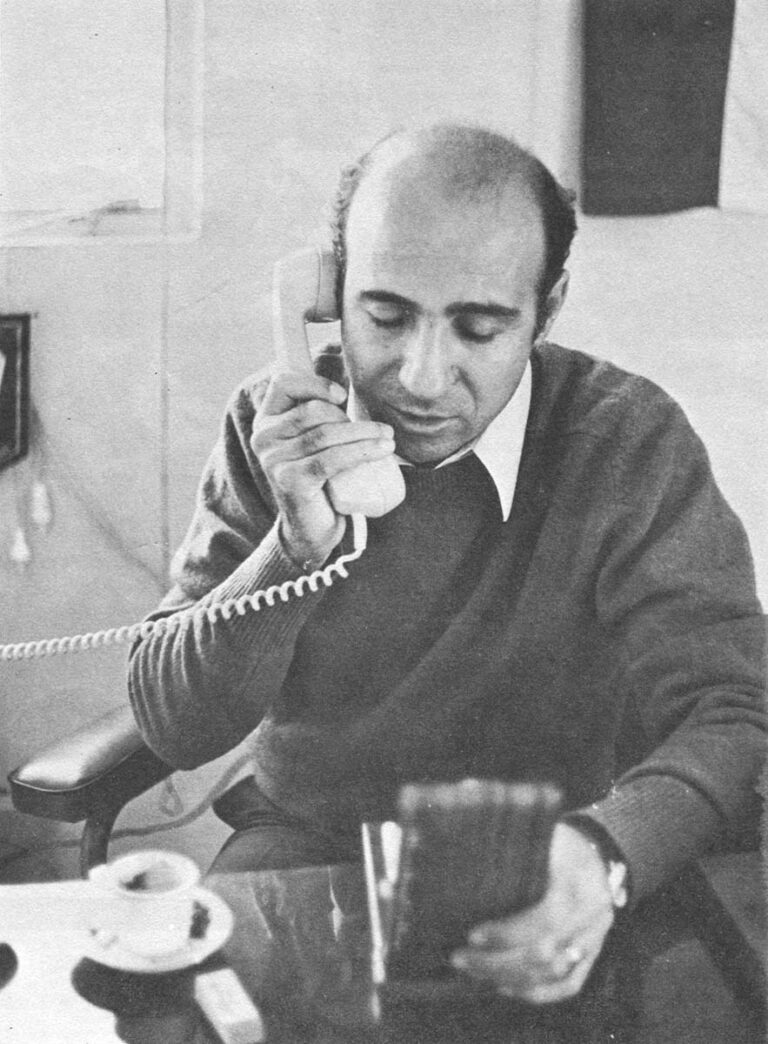

Ismail Shammout, the head of PLO’s Cultural Arts Center, designed that poster as well as the one, which made the September 29, 1970, cover of Time Magazine. He also makes movies and keeps a photographic archive of Palestine.

He claims to be “the first person in Palestine for centuries who took art as a profession.” He is court painter to the movement. Arab officials buy the originals; poorer men hang reproductions in their homes; the masses read his posters, which plaster walls in city and camp.

Soft-spoken and modest, Shammout, age thirty-nine, believes that he expresses the feelings of his people:

In my exhibitions in the Arab countries, especially in Jerusalem [pre-1967] where there are Palestinian people from different categories – ministers, doctors, peasant women in their national costumes – you feel that they are talking to the paintings and seeing themselves in the mirror. One boy selling newspapers in Jerusalem came every day for a week. I asked him, “What do you understand?” He replied that his father talked about Palestine but now he was seeing it.

At his first exhibition in 1953 in Gaza, “People came, looked, were moved, and cried.” What aroused them? Paintings like “The Spring That Was” which shows three beauties in Palestinian dress posing before workers picking oranges and gathering olives. “The girl in the middle,” explains Mr. Shammout “is Palestine with an olive branch.”

Shammout translates oral legends into symbols, which his audience can easily understand. He transmits verbal rather than visual concepts. Painting is a recent and still alien medium in the Arab world whose traditional culture is oral. Scholars speculate that while settled civilizations erected stone steles or carved bas-reliefs on temples, the nomadic Arabs composed poems and songs, which went with them where they wandered. Later visual expression was discouraged by the Muslim ban on representing the human figure which in turn deterred landscape and architectural painting. So Shammout and other contemporary Arab painters are newcomers still reflecting the value their culture places on the spoken word.

Furthermore Shammout, who is also a poet, consciously tries to express an idea in each painting. And ideas are words. “I always think there- is a message I have to give…I don’t create from the imagination. I take it [a subject] from stories I hear and things I see.”

Shammout calls his nineteenth century, representational style “realistic-expressionistic.” Critics call it sterile. But style is secondary to Shammout. He is a Palestinian first; then an artist. “An artist,” he says, “shouldn’t complicate himself with stylization and developments in art schools because he will lose his spontaneity of expression. An artist shouldn’t think of his style.” He criticizes his fellow Arabs who go to the West and change completely and are influenced by the outside world…First artists should express the problem of relations with people.”

Sitting in his PLO office dominated by his billboard size rendition of Gamal Abdul Nasir, Shammout describes his metamorphosis from refugee-artist to PLO publicist. A constant factor is his Palestinianess.

I was seventeen years old in July 1948, when we became refugees…. The first day’s walk from Lydda to Ramallah made me see things I never expected to see -people dying of thirst, hunger, terror including my two year old brother dying of thirst.

We had no money…I went selling bread. Then we went to Khan Yunis in the Gaza Strip. We were the first people arriving in Khan Yunis, where there are now 100,000 refugees. In Gaza I sold sweets to children for a year, walking twenty kilometers every day…I used to dream about drawing and painting and used to sit down crying. I had to think of the hunger of my family.

A year later when the United Nations Relief and Works Agency established a school in Gaza, Shammout taught art mornings and sold candy afternoons. At first, the school did not pay salaries.

They gave us old clothes and tennis shoes – never one pair. I had one white and one blue so I painted the white one with ink. My cousin had one blue and one red. He was ashamed to sell sweets to his students and used to cover his face with a kefiyah [the Arab headdress now recognized as standard commando gear]. But the kids recognized him by his shoes.

Shammout made extra money for the next year and a half when “someone would want a drawing of his dead father.” For four years, he studied art in Cairo supporting himself by painting cinema posters.

In 1954, Gamal Abdul Nasir, who had taken control of Egypt that year, opened Shammout’s first show in Cairo at the Egyptian Officers Club. Arab League officials and Yasir Arafat, who was then President of the League of Arab Students, attended.

Shammout attended Rome’s Academia of line Arts for two years and has worked for the Palestine Liberation Organization since its formation in 1964. That year the Arab Students Organization sponsored exhibitions of his work in America. In 1965, he exhibited in Russia. And in the same year, the PLO presented Red Chinese leader Chou En Lai “A Gun and an Olive Branch” by the artist.

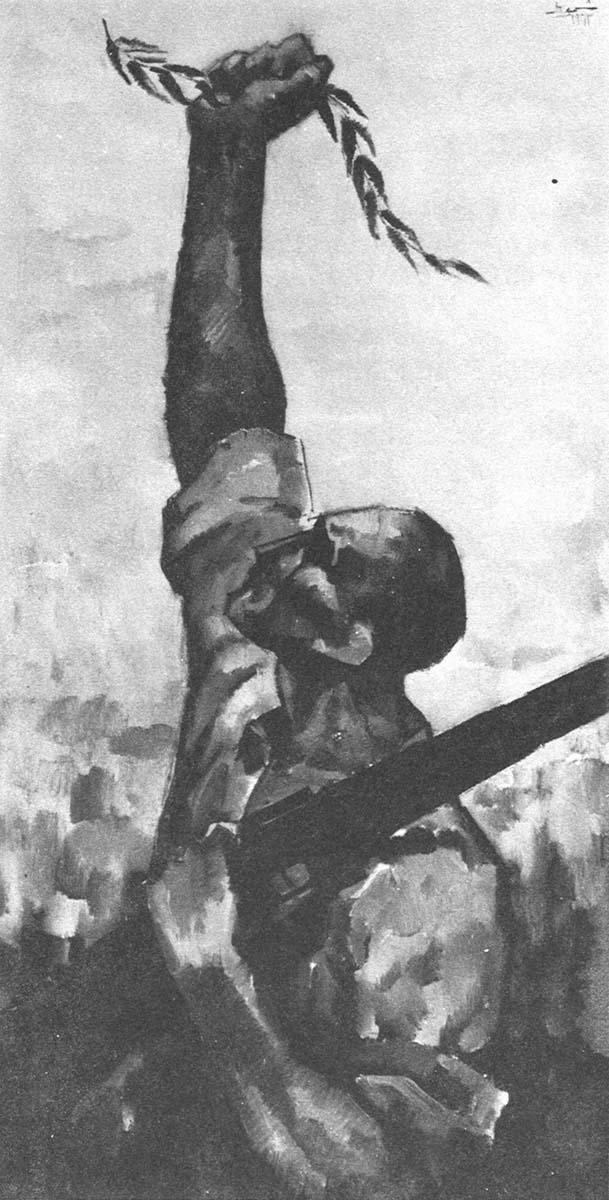

Although Shammout’s style has hardly changed over the years, the artist feels that his choice of themes expresses a shift in Palestinian self-consciousness from a “lost feeling” to “memories of home” to “more hope.” He is replacing the long-faced refugee with the determined guerrilla as the revised image of Palestine.

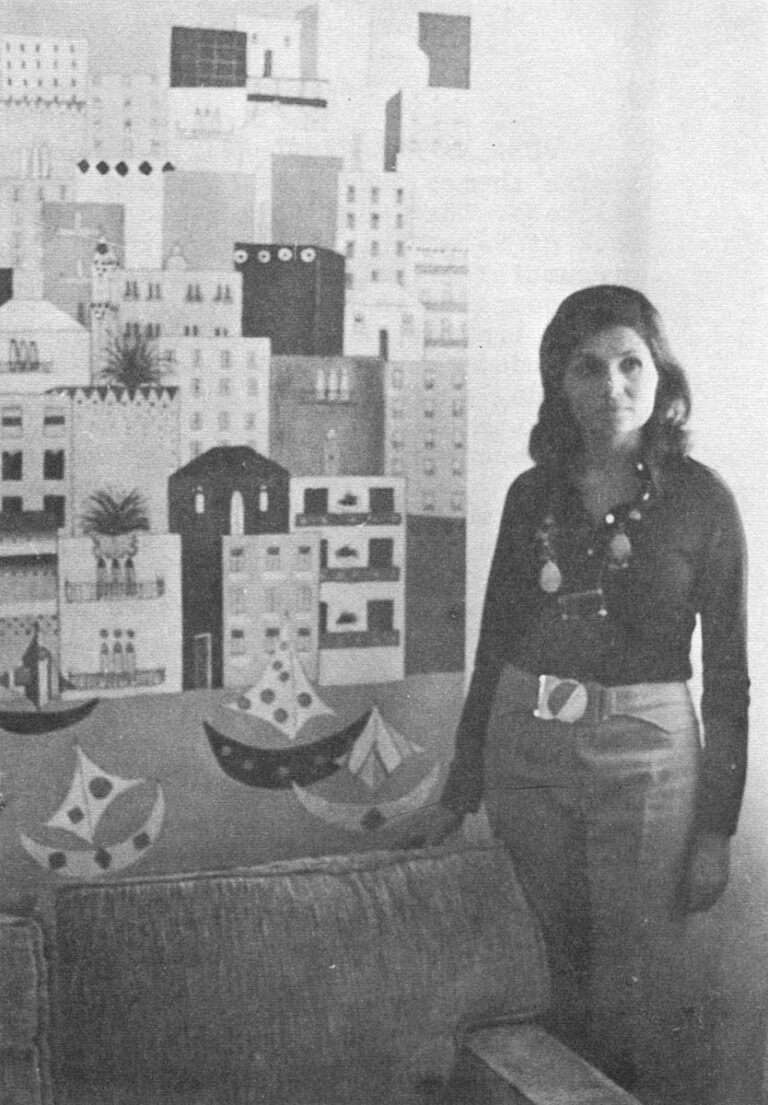

Jumaina Huessini Bayazid consciously paints Palestinian themes too. But her mood is neither tragic nor militant. Her work is a personal, anthropological notebook of Palestinian folkways including wedding ceremonies, circumcisions, and old wives’ tales. Her canvases are peopled with peasants in national costume or city folk in Western styles from British Mandate days in the Middle East. The Mandate however ended more than two decades ago, and today – like Ismail Shammout – Mrs. Bayazid says, “I am with every commando.” She feels a new dignity since “now we are fighting; before we just left our homes.”

Her work, which she calls “Pop Islamic”, is gay and decorative. Although rarely consciously political, it is inspired, she says, by the “always happy memories” of her childhood in Palestine which she left at age seventeen.

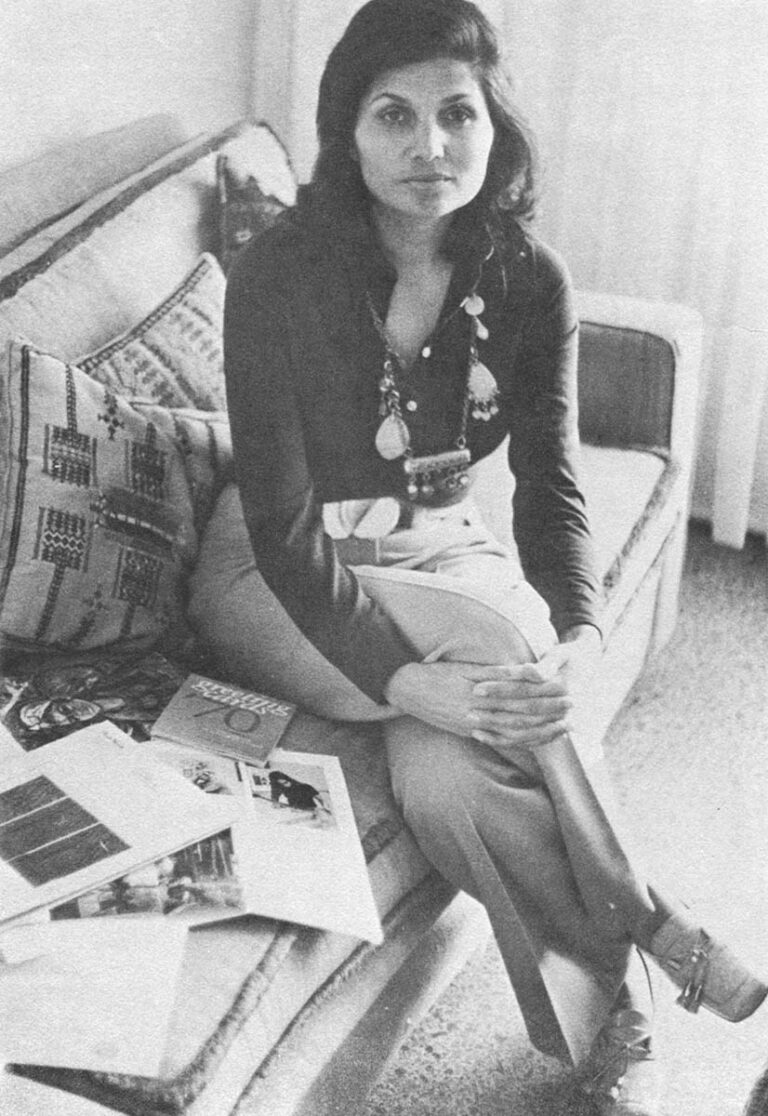

Today the dark-haired beauty in her late thirties lives in Beirut with her husband, a Syrian businessman. Sipping Turkish coffee served by the house-keeper of her airy apartment over-looking the Mediterranean, Mrs. Bayazid one morning explained that she prefers that “my maiden name, Husseini, be included in my name because it’s important not to forget Husseini since I’m proud that I am a Palestinian.” The Husseini family was one of the most powerful in Mandate Palestine.

Her childhood home is Jerusalem, where she “always saw and lived in houses with domes and old style windows” and which she tries to recapture on canvas. “Many people think I’m very religious. ‘Why always churches?’ they ask. It is my country – full of churches, mosques, and synagogues…Also many people forget the synagogues, but they are all there – all three.”

She continued, “In Palestine there were no modern painters or sculptors, but there was Jerusalem’s architecture and there were always people who painted walls, did stained glass, did the sculpture, and made icons.” Like the artisans of Jerusalem, Mrs. Bayazid does craft work in addition to painting. Carpenters assemble her carved wood panels and carved furniture legs to make heavy and impressive tables and chests. Families commission her to illuminate in arabesques their centuries old heirloom pages of manuscripts penned in elaborate Arabic calligraphy.

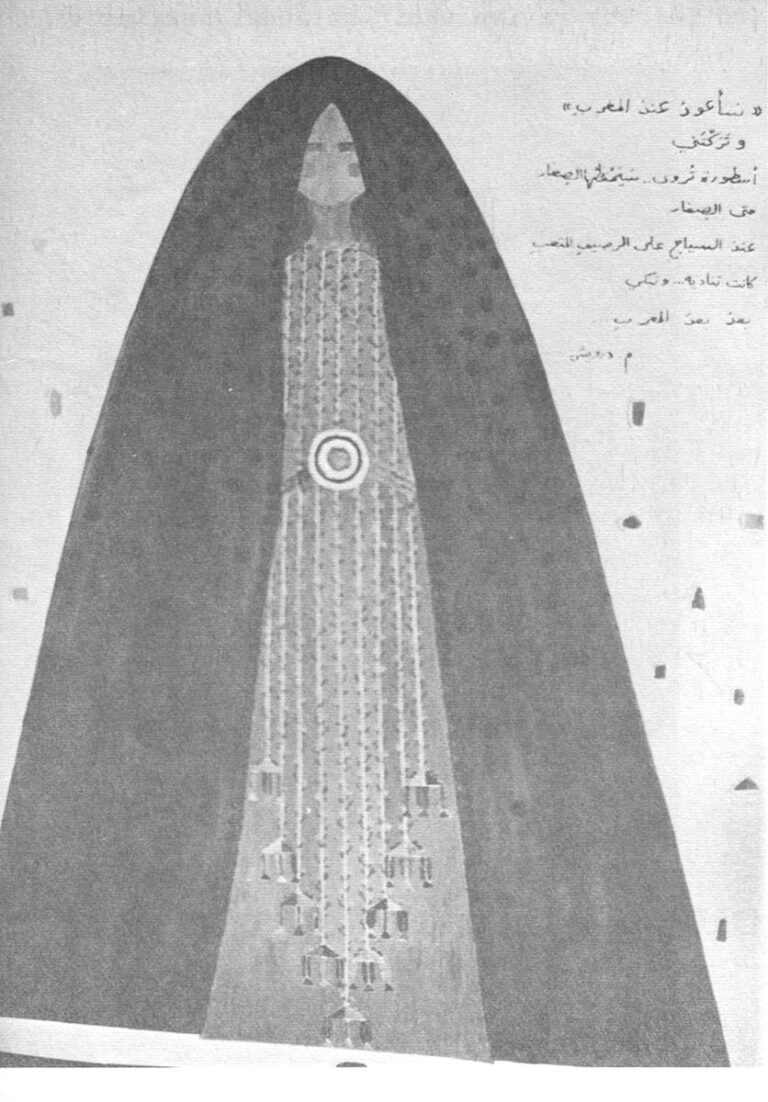

Influenced by medieval Islamic illuminations and calligraphy, she paints on the same canvas what she calls poetry from the resistance – usually by Israeli Arab poet Mahmoud Darwish – and her own figurative interpretation of the poetry. As with Shammout, the Arab oral heritage probably helps make her creations visual words.

The verse in the right-hand corner of one painting tells the tale of a maiden in an elaborate Palestinian costume. Although the poem is a sad story of unrequited love, Mrs. Bayazid, who likes to employ objets trouves, has whimsically decorated the paper-doll like girl with bits of mirror and bright colors. The naivete of her subjects and the artist’s flat, two-dimensional manner of painting is, she admits, “very primitive.” The artist puts on no airs. Like

Shammout she avoids discussions on style. Speaking with refreshing childlike simplicity, Mrs. Bayazid recalls, “When I was young I used to look for old stones and get beads from old bedouin jewelry. I found these things. I didn’t have to make them up.” A peasant mother would put a blue bead on a string and hang it around her baby boy’s neck for good luck; such a bead has found its way in the artist’s work to the navel of a stiffly carved, wooden female figure. And “Fatima’s hand” with an eye painted on its palm – the ensemble is a protection from the evil eye pops up frequently on her canvases. So does the Arabic expression “Ma Sha Allah” (What God Wills.)

The designs and bold color combinations of the Palestinian women’s ancient craft of embroidery also inspires Mrs. Bayazid. “A peasant girl used to sell eggs and buy thread. As she grew, she used to embroider her trousseau. After we lost Palestine – after we left Palestine – they stopped doing these things because there was no time or money.” But “after the war and the resistance formation” – in other words since 1967 – the artist and other prominent Palestinian women have been encouraging refugee women to take up embroidery again and thereby revive their national heritage.

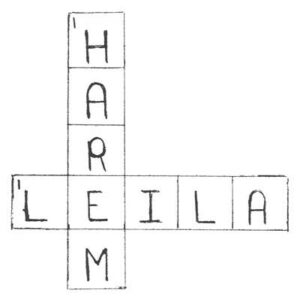

“I am an ‘I’ PERSON? NON-POLITICAL,” says Leila Shawwa, putting artistic before national self-expression. Actually she has more personal reasons than Bayazid or Shammout to take her Palestinian identity for granted. It is synonymous with her family name – as with Jumaina Husseini Bayazid. Moreover her family, the most important in Gaza, never abandoned its home – as did the other two artists.

The thirty-year old, well-groomed red head is proud to be a Palestinian, but feels that in painting “you must use your brains, as well as your temperament.” She explains, “I’m going to show the best culture. I don’t want sorrow for us – a crying nation…You can serve a cause, like Picasso’s Guernica, but you’re labeled as just that [part of the cause], if that’s all you do…I would like to help my country to the maximum, but within my possibilities.”

She studied at Rome’s Academia of Fine Arts, taught art education in the Gaza School System for a time, and has been painting on her own since.

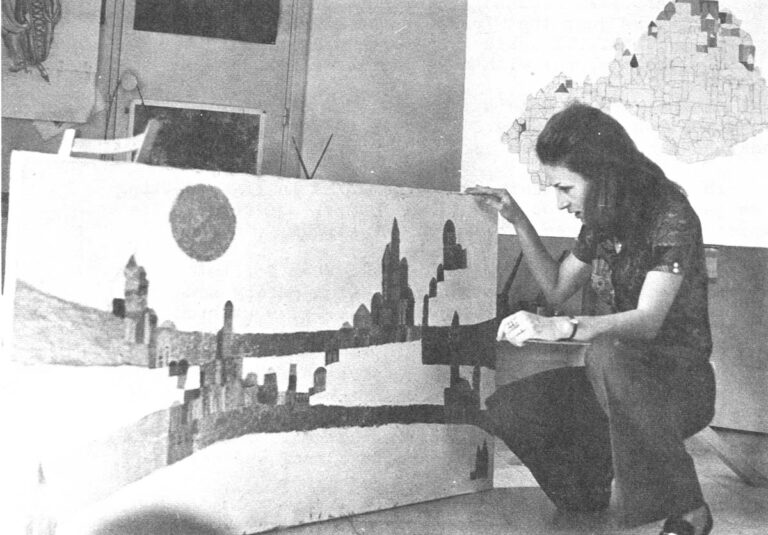

In her Beirut studio where she works in tight-fitting blue jeans, print blouse, and gold pumps, she reveals the impact which the June War had on her style.

“I went to Jerusalem after 1967…When I first painted Jerusalem, I did it out of a purely sentimental idea. But it developed…I’ve started painting other Middle -East cities as well.

…When I went to Israel the first time…the war had shaken me because I couldn’t believe they could take over and stay. When I had to go to Gaza, I dreaded it. I was an Arab, vanquished. I was in an occupied territory. You didn’t know whether you belonged.

Jerusalem was something else. I felt the pride of having once come from a people who made this. I felt I was an Arab. It touched me…I was impressed by it – the emotion – plus the colors and architectural interest.”

Miss Shawwa says that she has always been “obsessed” by the Middle Ages. She has studied medieval maps and city planning as well as painting and interior design.

Persian miniatures and oriental carpets and fabrics also give design and color inspiration for her intricate, geometric paintings. “It may look very primitive,” she explains, “but it’s a premeditated style, not naive.”

With shiny acrylic colors, black ink, and real gold or silver dust, Leila Shawwa builds oriental fairylands on canvas like castles in the air contrasting with her memories of her home Gaza, “a very unhappy place, the most squalid place anywhere.”

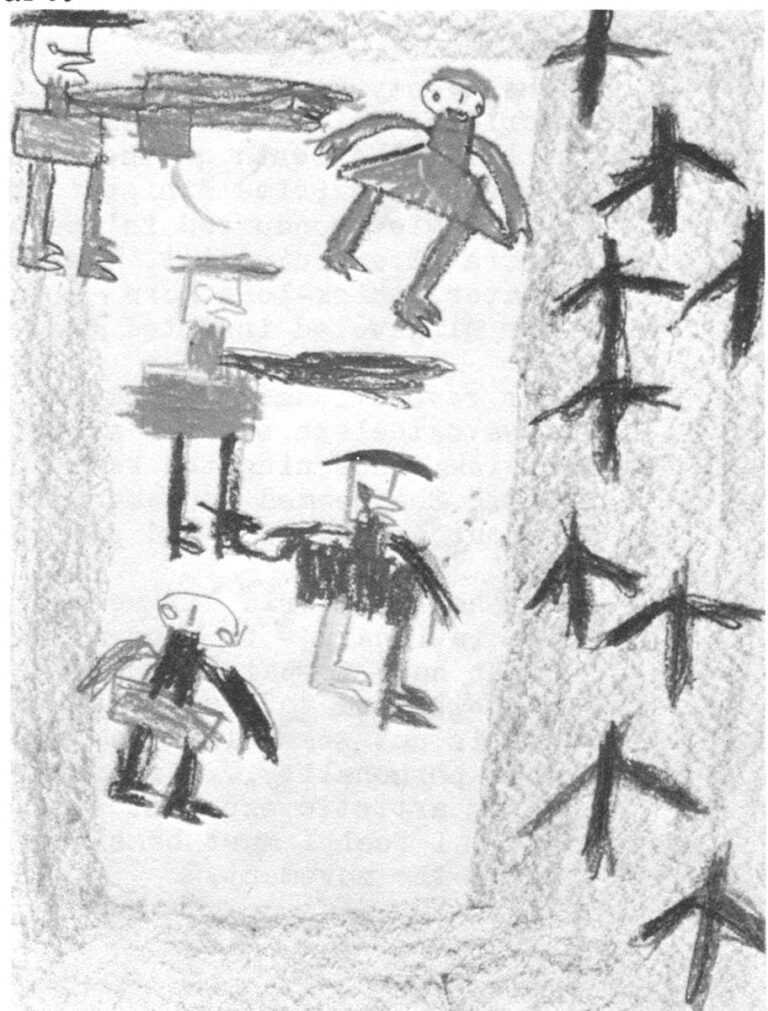

Mona Saudi is Jordanian. But she has skillfully edited and laid-out a book combining Palestinian art and politics. “In Time of War: Children Testify” is one hundred and eighty-eight color pages of drawings by Palestinian refugee children. Miss Saudi’s sponsor was the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, the Marxist commando-cum-skyjacking group which, calls for revolution in the entire Arab World.

Miss Saudi believes that “art is not revolutionary just by its expression; it is revolutionary by its function.” In this way, “the aim of the book is not to be an art book. Not all these children are artists. They are expressing a political case but in an artistic way.”

Miss Saudi’s political activities leave her little time or place for her own art work – sculpting the “simple, pure forms and abstract constructions” which she learned to execute in her studies in Paris. Her political connections for example took her on one of the PFLP skyjacked planes on its last flight from Beirut to Dawson Field, Jordan, where it was blown up last September. But at least Miss Saudi found the trip aesthetically pleasing: “The view of the planes in the desert was fantastic…I like simple landscapes – just light changing in color all the day. “

The twenty-five year old artist turned revolutionary made world headlines last year when Copenhagen authorities jailed her for a month on the grounds that she was plotting to assassinate ex-Prime Minister of Israel David Ben Gurion. In an interview conducted in one of Beirut’s cafes in the chic Hamra Street district, Miss Saudi wearing baggy slacks and sweater, thick-lens horn-rim glasses, no makeup and with her disheveled insisted that she was innocent.

Her revolutionary intentions are purely artistic, she said. Nevertheless she got artistically militant when elaborating on her views concerning the relationship between art and politics. She seemed to take a few intellectual swipes at Shammout and Bayazid and possibly Shawwa.

In the Arab World if we are going to do something revolutionary – to have a complete revolution – we don’t have to paint in a descriptive way. We have to go beyond to arrive at a revolution in art itself. Art is not something that comes from the surface of your personality…It comes from your depths. So my artistic expression is not direct political art. I feel I must be sincere with myself-and still serve the movement.

Although Miss Saudi’s place today is in a political huddle in Beirut or a refugee camp and not in an art studio, she has no regrets. She criticizes the vogue in Beirut art circles, which is “to be involved politically but to exhibit in fashionable places…. That’s not art: To draw tents or fedaveen…I don’t want to just work alone, be famous like others in bourgeois society and sell.”

Indeed a boom market for Palestinian art among the Arab radical chic tempts artists to paint to sell. One artist admits having two styles: commercial and artistic. And even Mona Saudi stoops to bourgeois practices of promoting her book for sale in the Arab World and the West. (It has an English-Arabic parallel text.)

These artists – who are in Frantz Fanon’s words using a “borrowed language,” painting – demonstrate how social and political factors mold individual artistic expression. All four artists donate work to the guerrilla organizations but none considers his work propaganda. Each does recognize however the political overtones in his work. And herein lies the pitfall. Being part of a people in search of a nation groping for a national Palestinian culture – is an attractive political cause for Ismail Shammout, Jumaina Husseini Bayazid, Leila Shawwa, and Mona Saudi. But it tends to encourage stiff and self-conscious cliches in their art.

Received in New York on June 23, 1971.

©1971 Paula Stern

Paula Stern, a free-lance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner. This article may be published with credit to Ms. Stern and the Alicia Patterson Fund.