June, 1971

Am Ajjai Fi Jerushalim…Lshanah Habah Byerushalaim…

Next Year In Jerusalem*

*From the Haggadah , the prayer book read during the Jewish holiday of Passover in Judeo-Arabic, Hebrew, and English.

“Isolated communities…in Southern Tunisia and in particular in the island of Djerba, which was cut off by the sea from any adulterating influences, provide us with the best source of information regarding Jewish life in North Africa before the arrival of the Spanish refugees. Here, where neither Spanish nor French influence penetrated to any appreciable extent Jewish life as it had been lived for centuries was retained in an almost pure state of preservation into the middle of the twentieth century.”

–From Andre Choraqui,

Between East and West, The Jews of North Africa, 1969

For the Djerban Jew, the present is the past preserved. He cherishes the glorious history and vivid legends of his forebears. The distilled vision of the romantic past is more pleasant to think about than the flies and filth in his hara (ghetto) in Djerba, Tunisia, today.

“We’re the oldest, living Jewish community in the world,” boasted one local Minever Cheevy. Tradition, supported by the island’s rabbis, dates the community from the period of the Babylonian Captivity following King Nebuchadnezzer’s destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem in 586 B.C.

Some scholars accept this oral tradition. N. Slouschz points out that there are several usages in the Djerban religious ritual contrary to the Talmud, which would seem to prove that the cult of the Jews of Djerba existed prior to the construction of the second Temple and therefore to the Talmud.

Some scholars accept this oral tradition. N. Slouschz points out that there are several usages in the Djerban religious ritual contrary to the Talmud, which would seem to prove that the cult of the Jews of Djerba existed prior to the construction of the second Temple and therefore to the Talmud.

Tunisian historian Salah Eddine Tlatli believes that the presence of a solitary sanctuary, the synagogue called The Ghriba (The Magnificent), which is several kilometers away from the hara, and site of an annual pilgrimage which draws believers from all of North Africa, provides a further argument in favor of the more ancient claims of the community. The synagogue is “a sort of modest restoration of the Temple, served by the clan of Aaronites and Cohanin who would be the origin of the numerous Cohen of Tunisia.”

The Ghriba, which one enters barefoot as in a mosque, is itself enveloped in layers of myths asserting that the synagogue houses the world’s oldest Torah (The Five Books of Moses written on parchment scroll), Tables of the Ten Commandments from the First Temple in Jerusalem, and stones from the First Temple – which local citizens sometimes claim fell miraculously from the sky thereby inspiring the synagogue’s construction.

There is also a purely pagan legend of the origins of this pious house of prayer. The Ghriba was a woman, a stranger, who landed in Djerba in a period, which is lost in the mist of the past. She had the reputation of a sorceress to the extent that the night when her hut burned no one bothered to extinguish the flames. At dawn the nude body of the Ghriba was found intact on the heap of ashes; the fire had burned only the hut and her clothes. A synagogue was constructed memorializing this underestimated woman.

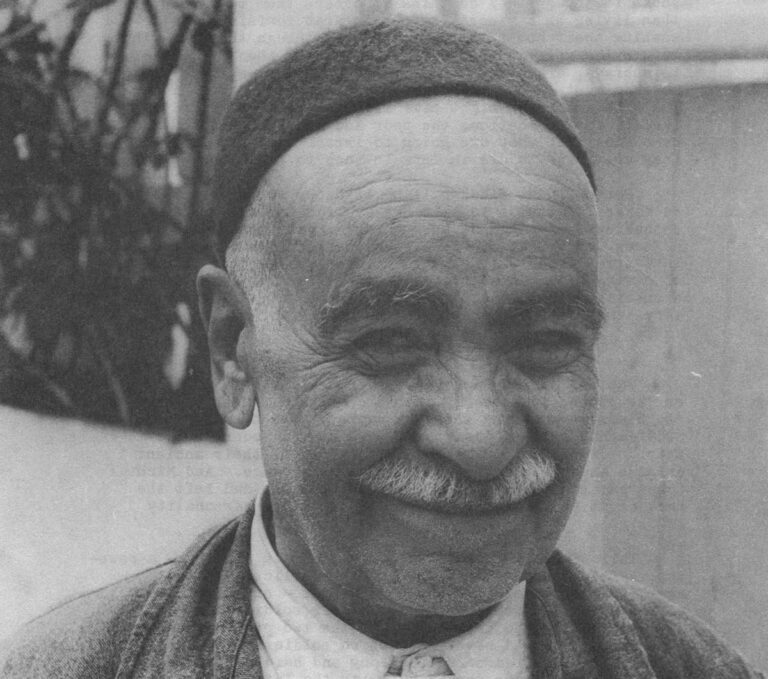

The Grand Rabbi of Tunisia, Reb Kbir Moshe Cohen, who is originally a Djerban, discounted these stories about the Ghriba. And when it came to the story of the sorceress, he clicked his teeth in disdain and waved his hand impatiently. He does however maintain the claim that Djerban Jewry dates from the destruction of the First Temple.

The presence of Jewish colonies in North Africa contemporary with Punic and Roman Carthage is no longer contested since the discovery of the Jewish graveyard in Gammarth, Tunisia, by R. P. Delattre. Further, according to historian Andre Choraqui, “The knowledge and presumably the use of Hebrew among the Jews of North Africa continued until the beginning of the Fifth Century C.E…The existence of Hebrew speaking Jewish communities in North Africa substantiates the theory that they left Palestine before their original language, Hebrew, had been supplanted by Aramaic…” But written documents supporting the ancient claims of the Djerbans have yet to appear. And there is another more likely thesis dating the community more recently toward the end of the eighth century C. E. following the Arab conquest of Tunisia when a part of some Judeo-Berber tribes fighting against Idris the First took refuge at Djerba.

Professor Paul Sebag – probably the best-informed individual on the subject – summarized what historians know about the origin of the Tunisian Jewry: There is no proof whatsoever that Jews settled in Djerba in 586 B.C., immediately following the destruction of the First Temple. The presence of a few Jews before the fall of the Second Temple is possible in Tunisia since there are ancient citations mentioning Jews being scattered throughout the Mediterranean Basin. And a group surely came to Tunisia when the Romans destroyed the Second Temple in Jerusalem. However, Tunisian Jewry is, for the most part, probably descended from Berbers converted to Judaism in the 6th and 7th centuries during the Byzantine Period in Tunisia. At that time, Jews from towns like Carthage fled from Byzantine religious repression to out-of-the-way, mountainous Berber areas and oases.

The Djerban Jew prefers his father’s legends to historians’ studies. The idea of descending from a cohen (priest) of the First Temple suits Mr. Cohen of today’s hara just fine.

The life of the Djerban Jew today is an epilogue to his ancestor’s mythology. He is a relic of the past, and this is the way he likes it. Like a widow forever drawn to the grave of her beloved husband, the Djerban Jew resurrects the spirit of his forefathers by repeating their ancient religious rites.

By strictly following the religious path of his ancestors, the Jews of the two villages Hara Kbira and Hara Sghira (Big and Little Ghettoes) have become a human island protected by religious ramparts in the middle of Djerba, the island made famous in antiquity as the Island of Meninx and as the isle of the Lotus Eaters, which Ulysses visited on his odyssey.

Traditional barriers are so effective that to this day the gray bearded Grand Rabbi of Djerba, who wears the traditional, puffy pantaloons with a black mourning band at the knee commemorating the First Temple’s destruction, has successfully resisted the establishment of a state school in Hara Kbira. He and the majority of the population whose thinking he influences know that students learning a foreign language like French—their native tongue is Tunisian dialectical Arabic pronounced with a slightly different Jewish accent and with some Hebrew words thrown in—and gaining exposure to the world outside the hara will begin questioning customs whose strength derives from the fact that they are embraced on faith. Thus today’s student from the hara must attend the religious school and learn Hebrew, the Bible, and the Talmud (religious commentaries). Or he must commute several kilometers to the nearest village that has a state school while he continues pursuing Talmudic studies in the hara. (The commuting student’s schedule is two hours in the state school, two hours more before lunch in the Talmudic school, two hours after lunch at the state school, and three hours in the late afternoon at Talmudic studies.)

The Grand Rabbi of Djerba, however, is fighting a losing battle, but not against the Tunisian Arabic culture, nor the North African French culture. Rather – paradoxically against the mutation of Judaism embodied in modern day Israeli society.

Twenty-five hundred years ago – still another legend has it – when Cyrus permitted the Jews to return to Jerusalem after their seventy-year-long Babylonian Captivity, an envoy sent from Palestine to encourage the Hebrew emigrants of North Africa to return was successful everywhere except in Djerba. Historian Tlatli suggests that doubtlessly the Jews had eaten the famous lotus. Tunisia’s Grand Rabbi explained that they refused to return before the Messiah came guaranteeing that the Temple would never again be destroyed. He reminded his listeners of the destruction of the Second Temple, which had been built without waiting for the Messiah’s arrival.

But Messiah or not, the Djerban Jewish community is finally leaving for Israel. In 1946, there were four thousand five hundred Jews divided between Hara Kbira and Hara Sghira. In 1956, two thousand ninety-one lived there. Before Passover and the May pilgrimage to the Ghriba in 1971, there were eight hundred in Hara Kbira and two hundred eighty-three in Haia Sghira. This summer approximately one hundred will leave. And it is only a matter of time when the others will join their families already in Israel.

Rigidly traditional communities that do not bend with change ultimately break under change. The tale of the extinction of the world’s most ancient Jewish settlement, however, is more complex than this general academic rule of modernization. Dying as a community, the Jews believe that they will be individually reincarnated in Israel. Phoenix-like – even like the Ghriba whose lifeless yet intact body was found on a heap of ashes but whose spirit inspired the construction of the Ghriba synagogue—the death of Djerban Jewry promises each Djerban Jew a new life in Israel. This conviction is expressed in a popular story told in the hara today….

Epic Tale – Odyssey From Hara To Israel:

Seventeen year old boy makes fifty cents a day combing raw wool in Djerba, argues with parents, runs away, joins Israeli Navy for three years, learns spoken Hebrew and English (even), forgets how to converge fluently in his native Arabic, marries European woman with blue eyes and blond hair (a Jewess, of course), has three lovely kids, and lives happily ever after.

As Witnessed:

By a Djerban Jew touring Israel, chancing to meet the run-away from Djerba, and returning to the hara.

As Told:

By many in the hara lo these eight long years since the boy’s flight.

Commentary:

(DJERBAN COMMENTATOR) “Here in the hara we are ashamed. We are timid. We are afraid to talk even to each other. There in Israel, there is a different feeling.”

(WESTERN COMMENTATOR) In Israel this modern day Ulysses who friends had described as “unqualified” and even a possessor of “bad blood” became a “new man, a man of valor.” Why? Inexplicable. Hence some sort of a miracle of fate. (Djerbans do not search for reasons or speculate on the unknown. They accept all as the will of God.)

Moral Of Story:

Odyssey from soporific isle of the lotus-eaters (with apprenticeship appropriately on a ship in the Mediterranean) and residence in Israel produces hero whose metamorphosis inspires others to shed their hara identity and become Israelis.

All those are good stories, legends, tales and myths. But the best one is still the one that gets told only once a year. It is the Passover story, the tale of the exodus of the Children of Israel from Pharaoh’s Egypt. And it was told with special poignancy this year since the exodus of the Children of Israel from Djerba, Tunisia, is in its last stages.

Passover is the happiest time of the year. It is the springtime of rejuvenation. On the island, which is usually bathed in sunshine year round, everything comes to life under occasional, always unexpected and soft showers. Wild flowers pop up in the olive groves and wheat fields. Almond trees blossom. And the leaves of the orange trees – specially cultivated for their fragrance rather than their fruit – rustle gently in the perfumed Mediterranean breeze.

For a month or so before the fifteenth day of the Hebrew month Nissan (in April according to the lunar calendar), the matzah bakery whizzes away producing enough matzah for the Djerban community – as well as some for Tunis whose matzah factory was burned June 1967, by angry mobs protesting the Arab-Israeli War.

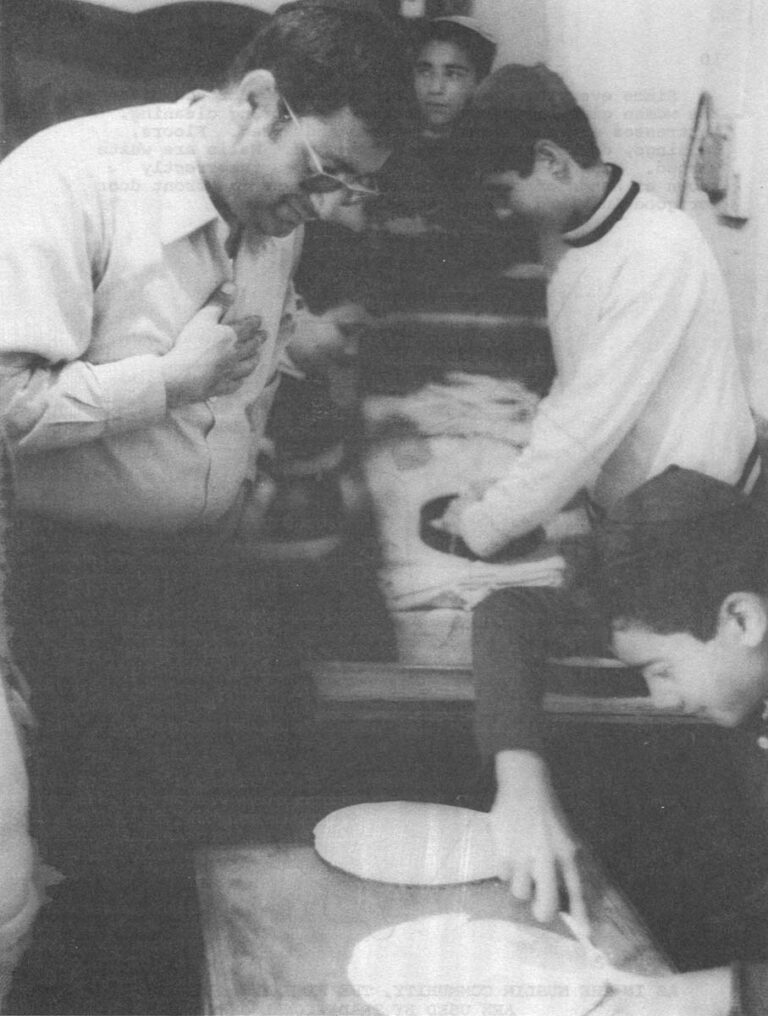

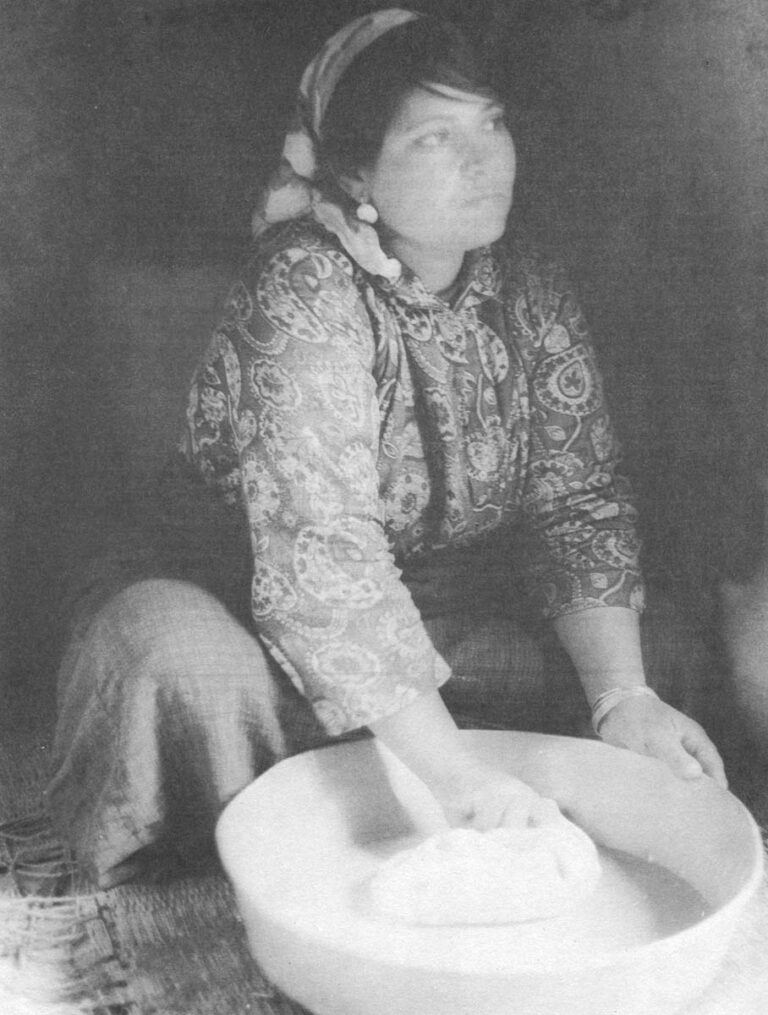

The female head of each household makes a few special schmura (guarded) matzah for the Seder, the religious ceremony preceding the Passover feast on the first two nights of Passover. The schmura matzah is made from flour touched only by strictly observant Jews – from the farmer in the wheat field, to the miller, to the woman who kneads the dough into a ball, to the second woman who pats the dough onto the walls of a circular, earthen pit oven heated by burning sticks. In the final stages of baking, a boy of age (thirteen years or more) stands by with his prayer book reciting a blessing over the holy bread.

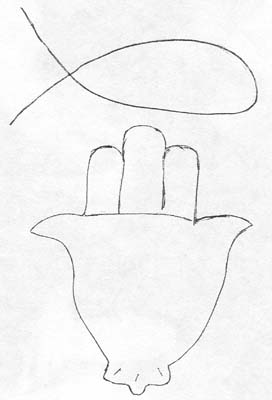

Since everything must be fresh and new for the holiday, the women give their houses a thorough spring-cleaning. Mattresses and cushions are remade and aired. Floors, ceilings, doors, and windows are washed. Walls are white washed. Blue fish and khomsas (sometimes incorrectly known as hands of Fatima) are painted over the front door for good luck and to beat off the evil eye.

Every cabinet and closet is emptied and cleaned. Dishes and food are removed, stored outside the house, and symbolically sold to Muslim neighbors to be bought back at the end of Passover week. Only new and specially reserved linens and dishes are used. And special food is prepared.

Lamb is the main item on the Passover menu – excepting matzah. Muslims even refer to the Jewish Passover as the Festival of the Lamb – ‘Id al ‘Allouch. One of the major prePassover events is the slaughter of the lamb. The only other time of year when a family slaughters a lamb is for Rosh HaShanah, the Jewish New Year. Although a family income may vary from four hundred to forty dollars a month, each family considers a lamb costing between twenty and thirty dollars a necessity. Without the paschal lamb there could be no real Pesach (Passover).

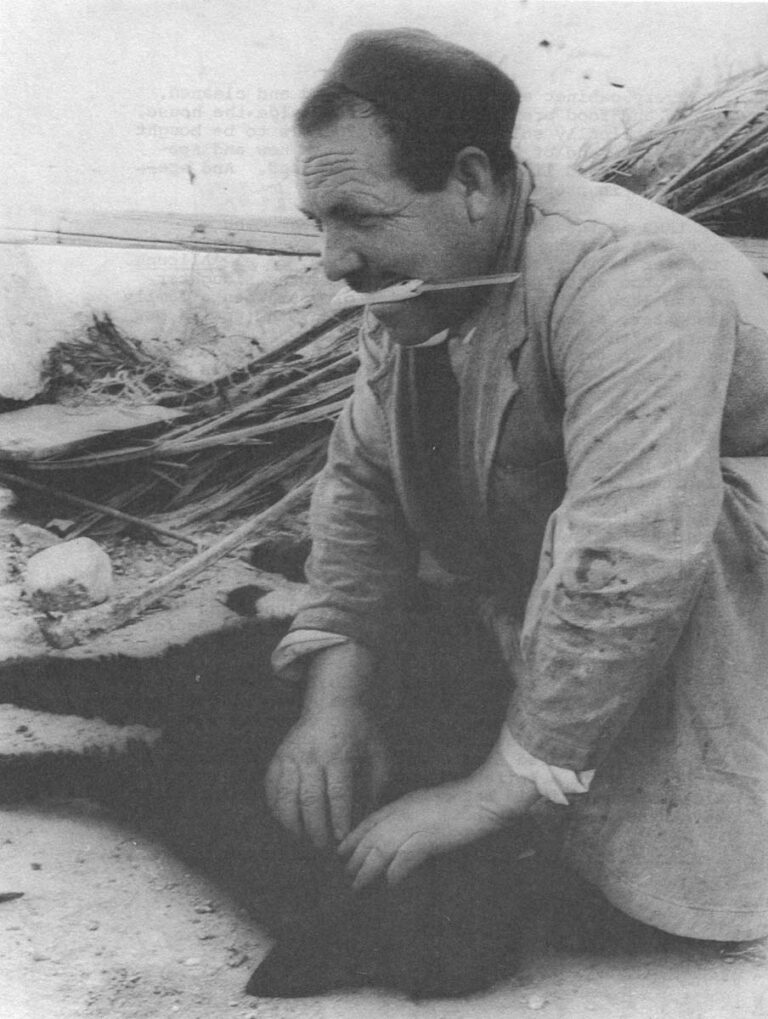

Exercising strict religious standards the rabbi, who is rather like a religious handy man since he is also teacher and butcher (shochet), monitors the event which may occur at the slaughterhouse or at home and which in both cases is swarming with curious men and children on-lookers. The lamb is killed by a quick slash to the jugular vein either by the rabbi-shochet or the owner of the lamb. The hide is cut away from the carcass and the body slit open. One man puts his mouth into the tubes leading to the animal’s lungs and blows, ballooning out the lungs so the rabbi can inspect for tuberculosis.

Rabbi Soosa of Hara Sghira – who for two days before Passover shuttled back and forth the seven kilometers between Hara Sghira and Hara Kbira overseeing slaughters estimates that one hundred and ten lambs were killed. He personally declared five unfit for Jewish consumption either because a knife had not been perfectly free of nicks or the animals had tuberculosis. (Muslims often buy these rejected lambs.)

After the animal is completely skinned, the women take over the job of cutting up the carcass and preparing the meat. They put the lamb’s head, a delicacy in Tunisia, over an open flame to burn off the hair. They use the meat in stews, for charcoal grilled kebabs, and for spicy meatballs called kifteh. They set aside one shoulder bone for ritual use -in the Seder, the Passover service. And they clean and stuff the entrails with parsley, lettuce, and spices to make the well-known Djerban Jewish sausage called osban.

The night before Passover the eldest male in the family conducts a search for the chometz, any non-Passover food and in particular any items containing leaven. By the light of wax and honey candles held by the boys in the family, the eldest male leads a room by room search pretending to examine every corner. He scrapes each shelf with a knife trying to find crumbs to put in a pottery dish – which he has spent a half-hour selecting and bargaining for in Houmt Souk, the main village on Djerba. Then a happy, candlelight, family procession shuffles out of the house and down one of the Hara’s dusty, smelly roads. The men pick a random spot in the road, dig a hole, smash the dish which has been stuffed with paper and with one symbolic, last crumb of leaven bread, burn this chometz, and bury it all.

Actually finding any chometz in this game is unheard of, for the women have been zealous in what they consider more a ritual cleansing than a spring cleaning of the house. The women – say the men, many of whom make and sell the famous Djerban jewelry in the tourist town of Houmt Souk and who are thus aware of life styles outside the hara – are more fervent in their religious duties. The women are generally confined to the house; they rarely even attend the synagogue, and if they do, they must stand outside and look through the bars of the synagogue windows at the men praying inside. However, during Passover, which centers around the home, the women welcome the chance to endow their domestic duties with spiritual meaning.

Passover actually begins in the evening with a religious service (Seder) at home followed by a feast. The day of the first Seder, the first born in each family must fast or go to the synagogue and recite a special prayer releasing him from the fast. After ten in the morning, the entire family eats only hallil, food specially prepared for Passover. In that way even their bodies will be ritually pure by the time Passover begins in the evening.

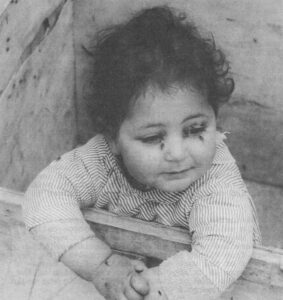

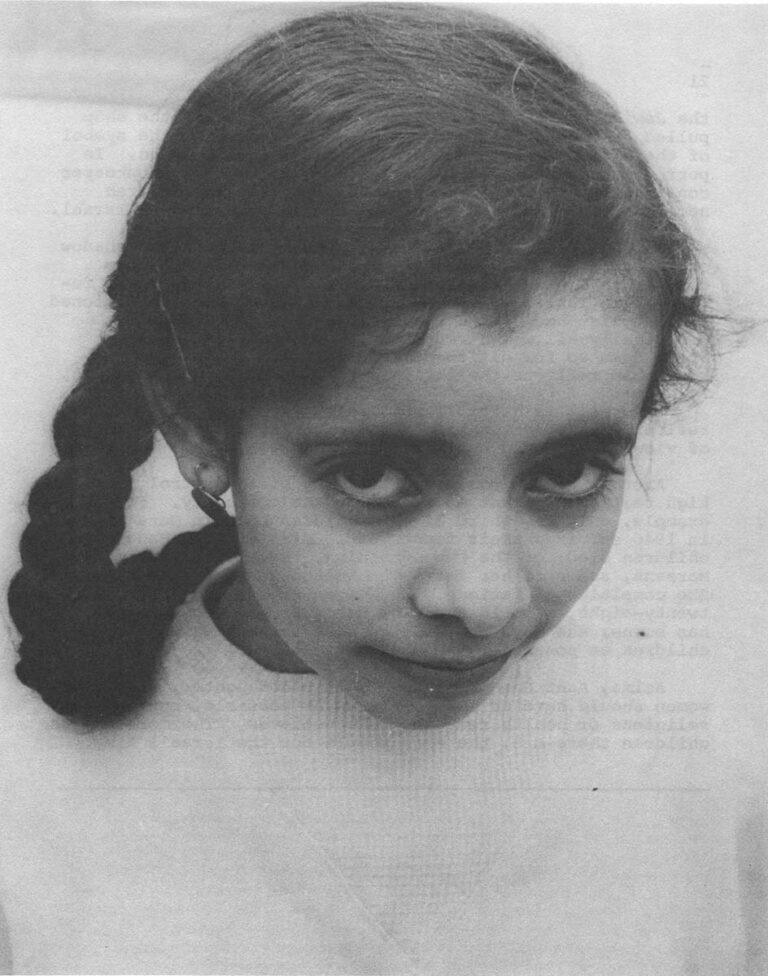

The last day before the first Seder is spent in last minute preparation. Having cleaned the house, utensils, and furnishings, the women turn to the family. They dedicate all their energy to the kids whose shiny, skinny, tanned, and wet bodies glisten in the sunshine in the open-air, inner courtyard where they squeal and run from the makeshift bathtub.

Passover is the time of new purchases too. The kids temporarily trade their dusty street clothes for new holiday outfits featuring chartreuse socks or fuchsia ribbons and other contraband items flooding Southern Tunisia from neighboring Libya.

As the sun begins to set casting a golden haze over the landscape and signaling the start of Passover, the women take time out for themselves. Sitting on straw mats in one of the six otherwise unfurnished rooms surrounding the courtyard of their North African style houses, the women help each other unbraid the plaits in their hair, pour over their heads local cologne which comes in quart bottles, and comb the sweet smelling liquid through their permanently pleated black hair. The older women don the gold diadem, which is unique to the Djerban Jewish women. The young women who say they are “modernizing” themselves simply cover their hair with a scarf and wear a modestly long dress instead of the yards of draped and folded cloth called the maliya. (Yehudith wears the so-called modern style. Hana wears a maliya.)

Instead of their everyday gray jackets and pantaloons with the black mourning band at the knee, the men wear white shirts and pantaloons. They drape themselves in white, hand woven burnooses reserved only for special occasions. And, as usual, they keep their heads covered with red woolen caps (which Muslim men also wear). The men also help each other dress, shave, or trim a moustache.

(Historian Andre Choraqui comments, “The manner of dress retained down to modern time by the Jews of…Southern Tunisia who had remained largely free of Spanish and French influences, is indicative of their oriental heritage, and gives some idea of what must have been current usage until the fifteenth century.”)

The whole family seems to gleam as they greet the Passover. Once the men return from praying at one of the fourteen synagogues in the village of eight hundred Jews in Hara Kbira, they begin the Seder.

At Michael Cohen’s house, the Seder was practically identical to the procedure followed in every other household in the hara. The Seder is a home service where everyone – that is all the males participate. Since it is a special night, the females get to eat in the same room with the males. But the women sat as usual on the floor while the males, though sitting on the floor, had mats and a squat table with a white table cloth and flowers. On the table, there was also a basket containing three pieces of schmura matzah, a lamb bone, a hard boiled egg, some celery, a heart of lettuce, and h’arrusot – a ball made from a paste of spices and fruits of the four seasons. Next to the basket, there was a bowl of salt water. These items symbolize the hardships of slavery and joy of liberation. The matzah is the bread of hardship and also a reminder of the unleavened bread which the Jews in flight from Pharaoh’s troops made and did not have time enough to let rise. The green herbs, symbols of new life of spring, are dipped in salt water, which is a reminder of the tears of bitterness shed by the enslaved Jews. The h’arrusot by its color is a reminder of the bricks and mortar of forced labor. The egg is a symbol of new life and also a reminder of the tricks of fortune. The lamb bone is the “strong hand” with which the eternal God delivered his people out of the house of bondage; it is also a vestige of the ancient practice of animal sacrifice.

The eldest male in the family leads the service. Even though the Seder was at Michael Cohen’s house this year, Michael did not lead it. Siddron, Michael’s uncle, who came from Matameur, a tiny village on the southern Tunisian mainland where there is only one Jewish family remaining and who was visiting Michael in the hara, took charge of the Seder. And Michael’s Aunt Hana, another visitor from Matameur, took charge in the kitchen over Michael’s wife Yehudith.

Seder in Hebrew means “order” and refers to the service each family follows according to the Passover prayer book, the Haggadah. Siddron used a Haqqadah with blessings in Hebrew and Aramaic and commentary in Judeo-Arabic, which is like an oriental Yiddish, a language written in Hebrew characters but when pronounced is local, dialectical Arabic.

Early in the proceedings, the children took the matzah and gleefully ran around the courtyard imitating the Jews’ flight from Pharaoh’s army and to freedom.

The highlight of the service was Siddron standing with the Passover basket, which he circled over the heads of the seated men, then over the women, and then even over the heads of the babies sleeping in an adjoining room. As he circled the basket over everyone’s head, the family chanted a spirited song about “Next year in Jerusalem.”

With the help of four glasses of homemade Djerban wine which each person must consume-during the Seder, the proceedings at the Cohen’s became increasingly lively. Since the Haggadah calls for four glasses of wine to be consumed, it is forbidden (haram) not to drink all four. Bokha, the liquor of fermented figs, a specialty of Tunisian Jews (and a favorite among Muslims who have released themselves from Islam’s ban against consumption of alcohol) is also drunk with fervor – religious and otherwise.

After the Seder, the Cohen family feasted. The traditional Tunisian dish for the holiday is msoki, matzah and lamb cooked in a sauce of all the vegetables of the season. This year Passover began on Friday night, the beginning of the Jewish Sabbath, which lasts until sundown Saturday, so the Saturday menu was affected by the Sabbath ban against lighting a fire to cook. The Jews of Djerba, however, have a way of arranging a hot meal for Saturday despite the ban. Every Friday evening before sundown, a member of each family takes his family’s pot of stew to the community oven. He announces the name of the family belonging to his pot, and the man in charge of the oven puts the pot on a long shovel and shoves it into the immense oven, which is lighted before Sabbath and allowed to burn through Saturday. Midday Saturday, the family representative fetches the warm stew. The Jews of Djerba have also found a way out of the Sabbath ban against any type work including carrying a pot of stew. The ban does not apply to someone carrying something in his own house. So the people of Hara Kbira have circled the village with a steel wire overhead and incorporated the entire village into one “household” where they can all carry items as if they were within their own family gate.

The first night of Passover at the Cohens’ was a success. Everyone glowed with holiday spirit. But the second night, Saturday night, holiday mellowness turned sour.

Siddron became ill, so the Seder was postponed until ten o’clock in the evening when he managed to rise from his mat and lead the Seder for a while. By the time he had rallied at ten o’clock, the children, who earlier in the day Yehudith had beaten forcing them to practice their passages in the Haggadah, had lost interest and fell asleep. Siddron felt compelled to return to the sickroom and after a long delay, a skeleton crew remained to finish the Seder finally at one o’clock in the morning.

Every holiday evokes memories of the dead and departed who are absent from the family celebration. And this Passover was no exception. Aunt Hana could not stop weeping over her mother who had died this year it was Hana’s first Passover without her mother and no one could shake the memory of the tragic events which had occurred in the past year and which kept pushing the group out of the holiday spirit and back into their normal, abnormal depression which hangs over the ghetto.

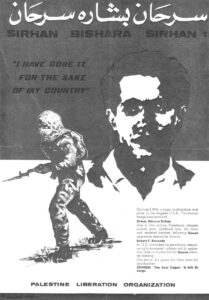

In February, on the eve of Id ikKbir, the Muslims’ major feast day and their own ‘Id-Allouch, Feast of the Lamb, a room in a synagogue in Hara Sghira was set afire. The Jews felt so intimidated that they informed the Jewish community in Tunis, the Capital, of the crime not by telephone – because a telephone operator can easily eavesdrop – but by the slow mail service. It was the market day in town and many outsiders were there; the guilty one escaped unnoticed. But the Jews are convinced that an Arab did it because the crime is so reminiscent of an event that occurred in the exact same room at the exact same time the year before.

Again on the eve of Id ikKbir, a rabbi wag knifed by an Arab and wounded so badly that he was hospitalized for twenty days, (The government authorities say they have arrested and confined the attacker to a mental institution.)

Two weeks before the synagogue in Hara Sghira was burned, a rabbi was shot and killed and two other Jews wounded in broad daylight on the streets of Tunis.

These attacks are spurring the exodus of Djerban Jews from Tunisia. Even though the Rabbi’s death took place in far-away Tunis, it has had a greater effect on the Djerban community than the fire or the stabbing in Djerba. “The Rabbi is the only person who has been killed,” one Jew stated very precisely.

There are other reasons to go. They say Jews have no future in Tunisia and that there are greater economic and educational opportunities in Israel than in Djerba. Moreover, living in the Holy Land is psychologically and religiously fulfilling for these observant Jews. And the women have an additional reason for wanting to live in Israel; they believe that in Israel they will be freer to leave the house – to go to a movie or to promenade with their husbands.

The Jews who remain in the hara are a sad and frightened lot. Their engrained minority habits of reserve stifle even spontaneous holiday joy of Passover. They walk through the hara as if on tiptoes. Even in their own ghetto where for centuries they have lived an autonomous existence according to their own rules, they are becoming a minority. The name “hara” meaning ghetto is even becoming a misnomer, since as Jews leave for Israel, Muslims from the South of Tunisia – from towns like Foum Tataouin, Medenine, and Matmata – who find work in Djerba move into Hara Kbira and Hara Sghira and are starting to outnumber the Jews.

The Jewish institutions in the two villages are in disarray. Leaders are lacking. The hara no longer has a cheikh or Rais al Yuhud (Head of the Jews) to represent it in its relations with the government. The more dynamic rabbis have already left. Even the charitable institutions like l’OSE – Oeuvre Secours Enfantine -, which is supported by the American Joint Distribution Committee, is closing its clinic this summer.

Everyone – rich and poor, young and old – knows that his days in the hara are numbered. But some families remain in the hara because of tragic circumstances – a relative too sick or old to leave behind or take with. Some families do not want to leave behind a house, which they have worked long and hard to purchase.

The richer Jews – usually the jewelers cum money-lenders do not want to leave their comfortable positions to go to Israel where they are sure of one thing – that it will take at least two years of time and lost income before they will be established and adjusted to their new country. Even though the rich give up more to leave Djerba, they are as religiously observant and as sentimentally attached to Israel as the poorer Jews. When a tourist in a Houmt Souk admired an antique oil lamp, a menorah specially made for the Jewish holiday Chanukah, the young patron of the shop pulled from under his shirt a necklace made from the symbol of the Jewish State, a menorah of a different design. In perfect conversational Israeli Hebrew, the young shopkeeper confidently announced to the foreigner that his menorah necklace came from HaAretz, “The Land,” referring to Israel.

The Djerban Jewish youth have been raised in the shadow of Israel. For them, Djerba, which may have a glorious chapter in Jewish history, is a dying community. Their future is in Israel. Even their thinking has been conditioned by the existence of the State of Israel. For example, practically all women reject birth control, but each age group does so for different reasons. And a teenager’s rationale reflects the influence of Israel on her thinking.

“The pill is haram (forbidden),” explained Aunt Hana reflecting a traditionalist, religious/superstitious point of view. She could not explain why it was haram.

Another reason for not practicing birth control is the high record of infant mortality in the community, For example, only one third of the children born in Hara Kbira in 1946 survived their first year. Five of Aunt Hana’s children died; of the two remaining, the eleven year old, Marzana, seems to her family to be too small for her age. She complains of fatigue. A younger mother, Yehudith, age twenty-eight, also lost one of the six children that she has borne; she says she will continue having as many more children as possible.

Aziza, Aunt Hana’s sixteen-year-old daughter, also says women should have as many children as possible, but not for religious or health reasons. She believes, “The more Jewish children there are, the more people for the Israeli Army.”

The young look forward to going to Israel, but leaving is hard on the older ones. They are proud of their ancient Djerban heritage. Many have stayed this long because they like life in Djerba. They feel compelled to leave only now that they are becoming a minority in the hara as other Jews leave and Muslims take their place.

Israel to them does not offer the hope it does the youth (although they do think it offers them more security than living as a minority group in Arab Tunisia). Whitewashing their homes for Passover even though they know that before the year is out, they will abandon them for Israel is a brave, dramatic, though vain gesture to stave off what to them must seem somewhat like a death sentence. Although the rich and young might have illusions of returning to Tunisia for a vacation, the poor and old like Siddron and Hana know that they are going to Israel once and for all. They are going to die in Israel not to find a new future.

Someone asks Siddron if he is happy to go to Israel. He makes an attempt to lift his eyelids and show some enthusiasm. How can he answer yes? Every spring flower he sees, every act of Passover he performs is done for the last time in Djerba. What makes him happy is the thought of having a lamb slaughtered for the Passover feast, making a special trip to the market town to select just the right pottery dish for the chometz, and searching for the chometz.

One day during Passover, Siddron and I were sitting on the ground in Michael Cohen’s courtyard. Hana and her daughters were making sausages nearby. The night before, Siddron had related the Exodus tale at the Seder. Other Djerban Jews had told me the old legends of their ancient origins and the story of the Ghriba synagogue. And Michael Cohen had spun the tale of the young boy who had left the hara eight years ago and who had changed his personality in Israel.

This time, Siddron asked me to read him a story – a newspaper article about the Arab-Israeli conflict. In the newspaper there were two war photographs – one of American soldiers in Vietnam and one of Israeli soldiers on the Suez Canal. If the captions under the two pictures had been switched, one would never know which soldiers were which nationality. But Siddron peered long and hard at the picture of the Israeli soldiers decked out with the latest weapons of war. Siddron touched the photograph trying to feel, communicate somehow bridge the gap between these modern Israeli Jews and himself. Siddron feels more akin to the past and Children of Israel in the Bible than to his Israeli contemporaries.

How can Siddron feel entirely happy about being “‘Next Year in Jerusalem?”

Received in New York on July 22, 1971.

©1971 Paula Stern

Paula Stern, a free-lance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner. This article may be published with credit to Ms. Stern and the Alicia Patterson Fund.