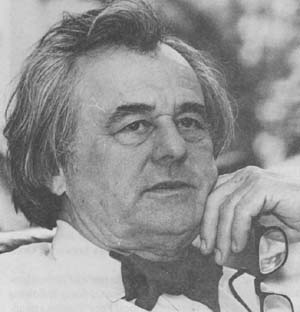

WASHINGTON, DC.–Bob Eckhardt, the softly drawling Texas Democrat whose bow ties and principled stands added a grace to the halls of Congress for 14 years, was beaten in the 1980 elections by a 28year-old Houston attorney who preached the Republican gospel of less government and lower taxes.

It was the shifting political wind that did Eckhardt in; that, and the three-quarters of a million dollars raised largely from corporate political action committees, which were more interested in defeating Eckhardt than electing his opponent, Jack Fields.

One of the corporations that helped to defeat Eckhardt was Occidental Petroleum Corporation, the oil, chemical and mining conglomerate whose subsidiary, Hooker Chemical Company, is headquartered in Houston.

The Fields-Eckhardt race was hardly more than a side bet for the strategists behind Occidental’s PAC. Fields was given $500 in an election year when the huge, computer-organized PAC dispensed nearly $120,000 to presidential, congressional, gubernatorial, judicial, and even Texas Railroad Commission candidates.

Since early 1978, when Occidental filed its first quarterly PAC report with the Federal Election Commission on a letterhead decorated with the stars and stripes, the committee has given away nearly $300,000. Most of the recipients were sure-bet conservative Republicans with free-market philosophies about big business, and fair-to-poor environmental voting records.

“Business knew how important it was to defeat my side,” said the 68-year-old Eckhardt, who is now practicing law in Washington, DC He noted with quiet irony that it cost his opponent $750,000 to win an election that, when Eckhardt first ran for office in 1966, only set him back $36,000.

“I had the reputation of being willing to listen,” Eckhardt said, sitting beneath a portrait of Sam Houston in his pleasantly chaotic office on Pennsylvania Avenue. “But some people in industry don’t want someone who listens, they want someone who obeys. If the climate is cooperative, they will reject someone who listens for someone who obeys.”

“I suspect that’s what happened to me,” he continued. “The climate in Washington today is running bullish for industry.”

Without intending to, Eckhardt became one of Occidental’s most persistent bugbears. He tended not to vote with his Texas colleagues in favor of oil companies, he supported tough toxic waste management laws, and his House Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigation publicly roughed Hooker up in a series of 1979 hearings on leaking toxic waste dumps.

In a Congress past, Eckhardt might have survived. But he and much of his liberal Democratic “side” fell victim to the fundraising power of New Right groups and large corporations like Occidental, which employed a phenomenon borne of loopholes in campaign reform laws known as negative spending. In that way, PACs can legally give money to opponents of out-of-favor incumbents.

Eckhardt holds a low opinion of PACs, which were spawned by the Federal Election Campaign reform laws of the mid-1970s with the intent of wresting political influence from the wealthy few and placing it in the hands of groups or committees of people.

The Political Buck

“They create institutionalized, sanitized, and ethical bribery,” Eckhardt said. “Everybody in Congress today is looking to PAC collections they can grab and, to a certain extent, they frame their positions toward that, although it is not an absolute quid pro quo.

“It used to be that you could listen to an issue and if you were for it, you could say ‘I am for it.’ But there is a reluctance on the part of Congress now to accept that kind of ukase (decree).”

Occidental’s PAC was part of the first bundle of corporate political action committees put together by astute companies in 1977–the same year that giant General Motors Corporation and American Telephone & Telegraph entered the PAC market.

Relying on payroll deductions from a wide variety of its employees–millionaire chairman of the board Armand Hammer gave $5,000 the same year that a Quebec-based bush pilot for Canadian Occidental gave $100–Occidental quickly built its PAC into a powerful machine.

In 1980, Occidental’s PAC funded a wide group of mostly conservative Republican candidates, including presidential contenders Ronald Reagan ($5,000) and former Texas Governor John Connally ($3,000). Using a typical PAC bet-hedging strategy, Democrat incumbent Jimmy Carter ($5,000) and Republican long-shot Benjamin Fernandez ($5,000) were also funded.

But the political buck didn’t stop there.

Occidental board members and their families supplemented the company’s PAC donations with private contributions from their own pockets.

Occidental president Joseph Baird added $1,000 each to Reagan and Connally’s campaign coffers. Baird was ousted in a mid-1979 corporate shakeup and his successor, Zoltan Merszei, gave $5,000 to Reagan and $1,500 to Connally.

Occidental vice president Paul Hebner gave $2,000 each to Reagan and Connally, and Hebner’s wife added another $1,000 to Connally’s campaign.

Mercurial chairman of the board Armand Hammer, a Democrat who pleaded guilty to providing secret, illegal campaign funds to President Nixon in 1972, handed out $26,000 from his personal funds to nine campaigns. In contrast to the Republican flavor of his corporation’s PAC, Hammer supported all Democrats. (His wife, on the other hand, spread her money in a wide, non-partisan circle. She gave $6,000 to Reagan, $1,000 to the Carter-Mondale team, and $1,000 to California Governor Jerry Brown for his presidential bid.)

The combination of Occidental’s PAC donations with corporate contributions on a private level only served to strengthen Occidental’s already-strong power base in Washington, where the company’s influential lobbyists (among them a rear admiral who served in the Kennedy Administration and a high-level Johnson administration aide) complement the social and business diplomacy of 83-year-old chairman of the board Armand Hammer.

The amount of influence lobbyists exert on Congress has always been difficult to measure, and so political analysts are turning more toward the relationship between PACs and candidates as a barometer of a company’s power in Washington.

PACs are supposed to spend money to influence federal elections and nothing more. Yet skeptics raise this “chicken-or-the-egg” quandary: do PAC contributions influence the way a legislator votes, or do legislators voting records influence PAC spending?

As the Sierra Club put it: “Which comes first? The money or the votes?”

In 1980, for example, Occidental supported 32 incumbents who voted in Congress against the environmental 88 percent of the time. In one important environmental vote, 21 of the 94 congressmen who voted against the successful chemical waste dump cleanup bill known as Superfund had received previous campaign donations from Occidental.

Environmental Action, a national organization which named Occidental to its 1980 and 1981 roster of “Filthy Five” companies (corporations with the “worst pollution practices and the most success in getting their friends elected to Congress”) noted that the five company PACs gave money “predominantly to incumbents with poor environmental voting records.”

Occidental also gave money to more than half of the 16 members of Congress elected to Environmental Action’s “Filthy $5,000 Club,” or those politicians who received the most money from the “Filthy Five” companies.

Not every candidate who got a check in the mail from Occidental kept it. To the astonishment of those familiar with the tight-fisted habits of political campaigners, some politicians gave the money back.

William Green, the Republican congressman from Manhattan, sent back the $500 check Occidental donated to his 1980 re-election campaign. So did Norman Lent, the Republican congressman from Long Island.

OMB director David Stockman returned a $1,000 campaign contribution to Occidental when he was just an under-financed congressman from western Michigan running for reelection in 1978.

Jack Kemp, another architect of economic policy in the Reagan Administration, returned Occidental’s $500 donation to his 1979 re-election campaign in upstate New York.

Five more congressmen running for re-election in the 1978 and 1980 campaigns sent money back to Occidental, as did two state legislators from New York, and a district court judge in Texas.

In a time of tumultuous campaign reform dominated by big-spending special interest groups, when politicians had to raise more money than ever before to get elected, Occidental found that its involvement in the energy business and the bloodied environmental reputation of its subsidiary, Hooker Chemical Company, turned good money to bad.

“I remember him saying ‘No. No way!’ when he got the check,” aide Hank Roden said of Congressman William Green’s reaction to a $500 donation from Occidental in 1980. “He just didn’t want to have anything to do with them.”

“Hooker is a company which requires a great deal of government examination–an exceptional amount,” Roden explained. “The congressman just felt uncomfortable accepting their funds.”

Thinking Twice about Contributions

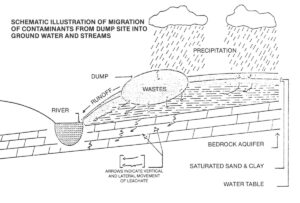

Not long after Occidental’s PAC went into business, the company was shaken by a series of public revelations about Hooker’s toxic chemical waste dumps, the most notorious of which was Love Canal. In New York alone, the state and federal governments are currently suing or negotiating with Hooker for the cleanup of four dumps in the Niagara Falls area and Long Island. Hooker agreed last year to spend $15 million to fix a fifth New York dump and settled out of court on cleanup plans for landfills in California and Michigan.

Hooker’s landfill problems caused some legislators to think twice about Occidental’s campaign contributions, particularly in New York, where there is substantial public concern over groundwater contamination from leaking Hooker dumps.

Long Island Congressman Norman Lent’s staff had instant recall of the $500 check he returned to Occidental in 1980 because “we don’t return all that many contributions;” aide Bill Roberts said.

“Hooker was under investigation by the House Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigation, on which Congressman Lent is the ranking Republican,” Roberts explained. “Hooker has a plant in Hicksville [Long Island] and has done some illegal dumping, which the congressman had uncovered. He went through records the subcommittee had subpoenaed from Hooker and found internal memos which revealed that Hooker had been dumping illegally at two landfills on Long Island for years.

“He felt that under the circumstances, certainly it was inappropriate to take the money. He thought it was a conflict of interest.”

Questions of conflicting interest also stopped two state legislators-whose upstate New York districts include Love Canal–from taking Occidental donations in 1980.

“I felt it better not to accept the money because I am chairman of the state Senate Subcommittee on Toxic Waste,” said Senator John Daly, a Republican from Niagara Falls. The returned $500 donation was no reflection of ill will toward Hooker, with whom Daly says he has a “good working relationship.”

State Assemblyman Matthew Murphy was deeply involved in negotiations for a $5 million grant from the state to revitalize the evacuated Love Canal neighborhood. The Democrat says he returned the $250 donation to Occidental because “I didn’t want the state, or anyone else to believe that I had any gain or possible involvement in Love Canal,” outside of his work on the revitalization project.

Other politicians who snubbed Occidental’s money were more concerned with the oil and mining conglomerate’s involvement in the energy field because of their assignments on energy-related Congressional committees.

Most, like David Stockman, had a policy of not accepting contributions from any company in the energy field. Some, like Jack Kemp, turned it down because “he just doesn’t take a lot of PAC money.” Others, like New Mexico Senator Peter Domenici, chairman of the powerful Senate Budget Committee, had a self-imposed limit on donations from oil companies.

The returned checks were probably frustrating to publicity-conscious Occidental executives, who insist that Hooker’s operations have been unfairly castigated in the press. But they would not talk about their political action committee except to say: “Occidental Petroleum Corporation does have a Political Action Committee, which is legally constituted and operated.”

Occidental’s influence did not end with the election. Once the Reagan administration was installed in the White House, the personable Hammer, who is said to have known every president since Herbert Hoover, set to work bolstering Occidental’s image in Washington.

The 83-year-old industrialist, art collector, and philanthropist underwrote the cost of a post-rehearsal party following the star-studded fund-raiser for the local Ford Theatre attended by President and Mrs. Reagan and most of his cabinet. The party was held at the Corcoran Art Gallery where Hammer’s most recent acquisition, the $5.2 million Leonardo da Vinci manuscript “Codex Leicester,” was exhibited as one of the first events of the 1981 inauguration festivities.

A Gift for the Reagans

Later in the year, when the Reagans appealed for private help in redecorating the White House, Hammer sent along a check for $20,000. He subsequently gave a speech urging the largely pro-oil Reagan to support synthetic fuel production.

This past Christmas, the industrialist was reportedly negotiating for the purchase of a Jamie Wyeth painting of the White House–which decorated the President’s Christmas card this year-as a private gift for the Reagans.

Dr. Hammer, as he is known, also heads the president’s three-man Cancer Advisory Panel, a position from which he recently announced a $1 million reward for a cure to cancer. The offer was jeered by a group called Citizens against Corporate Cancer, who called on Hammer to resign from the panel because, they charged, Hooker Chemical Company is responsible for widespread pollution that causes cancer.

Dr. Hammer’s adept social diplomacy in Washington is matched by the political maneuverings of Occidental’s powerful lobbyists. The lobbyists, in turn, are supported by a corps of government affairs officers whom Occidental says are engaged in “research, gathering and dissemination of information, in business contacts with government departments and agencies (on the public record), and in contacts with officials of foreign governments.”

But Occidental’s most powerful ally in Washington is likely the Chemical Manufacturer’s Association, an aggressive trade organization which reportedly spent $8 million on a recent advertising blitz designed to influence “thought leaders” and lift the chemical industry from its rock-bottom position in public opinion polls.

“We are working,” ex-Hooker president Bruce Davis told Eckhardt’s Congressional subcommittee, “through the Manufacturing Chemists Association [now the CMA] to make our views known, and to help to develop recommendations for proper and suitable legislation.”

As an example, in 1980, Hooker and other chemical companies worked in tandem with the CMA during the long Congressional debate over the beleaguered $1.6 billion Superfund plan to finance the cleanup of abandoned waste dumps through a tax imposed on industry.

Superfund

Hooker president Donald Baeder (now an Occidental vice president) and Hooker vice president Lewis King traveled to Washington to talk to Eckhardt and other legislators involved with the bill.

Reasoning that Superfund was a direct result of the Love Canal tragedy–where several hundred homes had been evacuated two years before in the wake of public health warnings, which some critics charged was unnecessary–the Hooker executives wanted Congress to know the full story behind Love Canal before new laws were passed.

“We said, ‘Before you agree to set up a huge fund, we think you ought to have some facts about Love Canal,’ ” King recalled. “And we said, secondly, that we encourage someone to come forth with an amendment to Superfund saying that before the government attacks any problem, they first have got to get data and find out what the facts are before they go out and create a panic the way they did at Niagara Falls.”

The company even paid an attorney to draft such an amendment to Superfund as an example of what Congress could do and, according to King, “as a way of trying to control the Environmental Protection Agency and the way they moved ahead on this.”

Hooker’s amendment was not successful, but Superfund was. The CMA engaged in some last-minute waffling on the bill after the pro-business Reagan Administration was elected, but the fund prevailed and was made law during the waning days of the Carter Administration. Budget cuts have since threatened the effectiveness of Superfund, which has fallen victim to the changing regulatory mood and the increasing dominance of industry’s voice in Washington–a mood which Hooker executives say is long overdue.

©1982 Cathy Trost

Cathy Trost completes her investigation of the evolution of toxic pollution policy in the U.S. with this issue.