LATHROP, Cal.–The day after her 27-year-old husband died, Marta Trout and her relatives conducted a wake of sorts in front of the living room television, where the president of Hooker Chemical Company was being interviewed on -60 Minutes.”

Mrs. Trout was struck by something the Hooker executive said on that bleak Sunday evening, just a few days before Christmas, 1979. She can still repeat it word for word: “No one has been hurt at Lathrop. No one. No one has been hurt and no one will be.”

“We all sat there and watched this guy say these things big as life. It was the biggest lie,” recalled Mrs. Trout, 26, from her ranch-style home in the San Joaquin Valley, which she has decorated with photographs of her husband and his collection of amateur baseball league trophies. Her tow-headed son sat on his mother’s lap, sucking his thumb. The boy was too small when his father died to remember him now as “anything but a picture. “

Michael Trout died December 15, 1979, from a hemorrhage caused by a brain tumor. Until two days before his death, he worked as a line operator in the AgChem division of Occidental Chemical Company, a subsidiary of Hooker Chemical Company, which makes pesticides and fertilizers. The line operators formulated more than 200 pesticides, but their main task by far was mixing up batches of DBCP (1,2dibromo-3-chloropropane) that were brought over from the manufacturing reactors. The workers added solvents and emulsifiers to the dried DBCP, transforming it into an amber liquid. It was then measured into cans and stacked in the warehouse for shipment. D13CP was much in demand by farmers across America for control of tiny worms called nematodes, which ravage crop roots.

Four years after starting work at Occidental, Trout had surgery for removal of a cancerous brain tumor. The following year, he was one of 21 men working in the Ag Chem plant who were found to be sterile or to have unusually low sperm counts. Subsequent medical studies linked the workers’ infertility to their contact with DBCP, which causes cancer and sterility in animals.

Just as Love Canal had become notorious as the first widespread eruption of toxic chemicals longburied beneath the ground, Lathrop became known as the first major episode in the United States of worker infertility related to occupational exposure to chemicals.

The sterility epidemic confirmed what scientists had been thinking for some time. “Prior to the time D13CP was found at Lathrop in 1977, the concept that specific agents can harm the male reproductive system was theoretical,” says Dr. Donald Whorton, the medical consultant who originally tested the Ag Chem workers. He is conducting followup studies on the 12 workers who are still sterile four years later. “DBCP made this no longer a theoretical issue, but a real issue,” he says. “There was clear, unequivocal data that showed males were clearly harmed by exposure to the agent.”

Evidence of the hazards of DBCP had appeared 15 years before the sterility was discovered among workers at Lathrop. Various research studies done for the Shell Chemical and Dow Chemical companies in the late 1950s and early 1960s all pointed in the same direction: DBCP caused sterility in lab rats. Shell’s study reported that lab rats who inhaled DBCP had reduced or abnormal sperm and the 1961 Dow study concluded that “the most striking observation at autopsy was severe atrophy and degeneration of the testes of all [rat] species.”

An avalanche of lawsuits was filed against Occidental in the wake of the sterility scandal. A class action suit was filed on behalf of 30 workers, along with an assortment of other legal actions centered on the plant’s production and disposal of D13CP, which was banned nationally in late 1979. The workers are trying to prove that Occidental and the other companies (Shell and Dow) had a longstanding knowledge of medical tests linking DBCP to sterility in test rats-knowledge which was not passed onto the workers.

A state superior court judge in San Francisco is currently, trying to devise a plan to consolidate the litigation-about 35 separate suits-for a trial sometime next spring.

Michael Trout’s widow is convinced that his death was caused by the pesticides he worked with at Occidental Chemical. She has filed a $4 million wrongful death suit against the company. “If you could have seen the man he was when I first met him and the person he was after,” she said, her voice trailing off into memories. “I don’t care if it takes ten years to settle this case, I won’t give up.”

“We had been trying from the time my first son was two to have another baby,” Mrs. Trout said in a bitter monotone that matched the hard set of her young face. “Mike had been telling me long before then that the guys down at work had been talking about how no one was having babies. I felt that the sterility thing was harder on him than the cancer. He was crushed, and the whole thing just about destroyed our marriage. “

Trout eventually recovered his fertility, as did four other Ag Chem workers with low sperm counts. His second son was born 13 months before he died. “Matthew did so much for his spirits that he was better for awhile,” Mrs. Trout said, “but then I began to notice a change. He was moody and forgetful, he was off work for six weeks with vomiting and severe headaches, and then he went back to the Ag Chem line. They didn’t bother to tell me how sick he was at work, that he couldn’t even count to 100 on the bag lines.”

Playing with DBCP

Farnham Soto, who was one of Trout’s co-workers and golfing partners, worried about his friend’s advancing illness. “He had a bottle of Excedrin in his locker and he’d take eight or nine of them at a time, but they wouldn’t do anything for his bad headaches,” Soto said- “His reaction time had slowed down considerably and the supes [supervisors] were harassing the crap out of him. They were going to give him a reprimand the day before he ended up going into the hospital for the last time. I went in and told them, ‘Hey, Mike is sick.’

“When he got sick, they just figured he was goofing off,” said Soto, who was the representative, of the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union in the Ag Chem Division. “Ag Chem had the worst absentee record in the whole plant. You work with insecticides and pesticides day after day and your resistance just isn’t what it should be. The guys handled DBCP like you would water. We played with DBCP. If you had a puddle of it, you’d flick it around with your fingers. You got your hands in it and you got it on your skin, and the vapors were all over the place.”

Occidental wasn’t necessarily an “industrial bandit.” Policy on handling DBCP was the same at Occidental as it was at Dow Chemical and other firms where the pesticide was produced or formulated. Once the sterility was confirmed in the late summer of 1977, formulation of DBCP was immediately stopped at Lathrop and assembly line safety equipment was augmented.

Despite the links suggested by the research, the sterility lawsuits may languish in the courts for years because of the difficulty of proving to the law’s satisfaction that a specific chemical causes a specific health effect. Even though Marta Trout is convinced that her husband’s temporary sterility and eventual death were caused by his work with DBCP, she may not be able to prove it in court.

The most troubling lawsuit of all for Occidental was concluded out of court last February when the State of California and the Federal government reached agreement with the company on a groundwater cleanup plan for the Lathrop plant, which sits about 70 miles east of San Francisco. The state and federal governments had filed a double-pronged lawsuit against Occidental in late 1979, charging that the company knowingly dumped pesticide wastes on the ground around the Lathrop plant in violation of state laws.

As Farnham Soto, who still works for Occidental, says, “I don’t think the company is too awfully worried about suits filed by their own employees. They were more worried about the state because it has clout.”

The company was also feeling the pinch of publicity from Hooker’s involvement in the Love Canal dumpsite in New York. In an internal memo written shortly after the California lawsuit was filed, a government attorney in Washington talked about the pressure Hooker must have been feeling because of the Love Canal uproar, which had grabbed headlines the year before. “While its lawyers may want to litigate the hell out of the [state and federal] case, ” the attorney wrote, “this arguably may not be in the company’s best publicity interests. (Headlines: The Coast-to-Coast polluter).”

Occidental officials contend that huge sums of money were diverted into pollution controls at Lathrop once the industry’s environmental awareness was increased, along with the rest of the country, in the 1970s. “Between 1970 and 1978, we spent something like $9 million on the Lathrop plant -whose total value isn’t worth more than $80 or $90 million -on improving environmental controls,” said Donald Baeder, vice president for science and technology of Occidental Petroleum Corporation, the umbrella company which owns both Occidental Chemical and Hooker Chemical.

In addition, Occidental installed huge storage tanks in mid-1976 and began collecting the toxic wastes there for removal to state-approved landfills, eliminating the company thought, all waste discharge problems.

“Baloney, ” scoffs Harold Eisenberg, the assistant state attorney general who directed California’s lawsuit against Occidental. “Over the past 30 years, Occidental couldn’t have cared less about cleaning up its toxic wastes. It took a lawsuit to get any action out of them. Now they’re paying lip service to this cleanup program. Let’s wait and see.”

A Charles Bragg cartoon hangs on Eisenberg’s office wall. The cartoon “will tell you more than anything else how this case with Occidental was settled,” he says. Captioned “Outof-Court Settlement, ” the cartoon portrays two lawyers throttling each other, their pipes flying every which way, ties and briefcases askew.

“In their defense, most people who worked in the chemical industry during the 1960s felt they were going out and saving the world with chemicals,” Eisenberg conceded. “But that facility out there in Lathrop was never concerned with the proper methods of disposal. Their consciousness was just not there. It was bucket shop chemistry-just dump it out the back door.”

Occidental Chemical bought Best Fertilizers in the spring of 1963 and soon began manufacturing and formulating (mixing together and packaging) numerous insecticides and pesticides. The local economy was tied to the plant like an umbilical cord, which Occidental proved by running a promotional stunt in 1968. The weekly payroll was distributed in marked $2 bills, which were tracked throughout the stores in the community to show the townspeople how they benefitted from the Occidental jobs. That economic dependency was driven home more poignantly years later when sterile and lowsperm men clung to their jobs at the plant, despite the health risks. “I’ve got a house, a mortgage, and four kids going to school,” explained Farnham Soto, who had a vasectomy before the sterility was discovered at Lathrop, but worries about cancer. “Most of the other guys feel the same way.”

Besides DBCP, the Ag Chem workers were also formulating a number of widely used organophosphate pesticides such as Parathion and Malathion. For that, they wore protective gear and rubber gloves because the chemicals were toxins related to the nerve gases developed by the Nazis during World War 11. Even with the safety precautions, the “poisons,” as the men called them, often felled the workers on the line.

“We were running Toxaphene one hot day in July a few years ago, it must have been about 100 degrees,” recalled Farnham Soto. “They had run Phosdrin the day before and some of it must have spilled in the conveyor belt when they were canning it out. The line wasn’t running well so I took my rubber gloves off and I must have laid my hands down on the belt. It wasn’t 15 minutes later that I was vomiting, nauseous, very ill. My supe said: ‘Maybe you’ve got the flu.”’

Soto was hospitalized overnight with what the doctor described as phosphate poisoning. The company doctor, on the other hand, told him that he was fine and could go back to work. Instead, Soto said he was off work for six weeks, too weak even to stand up for long periods of time.

“The guys were very careful with the poisons,” Soto remembers. “But the rest of the stuff, the DBCP, nobody ever said: ‘This is going to hurt you.’ I don’t think our department heads knew the implications of DBCP. “

“That’s true,” said Mel G. Rice, Occidental Chemical’s Vice President and General Manager. “The problem with DBCP was that we were not aware of the hazards of the chemical. It was generally treated as a harmless or relatively harmless chemical.”

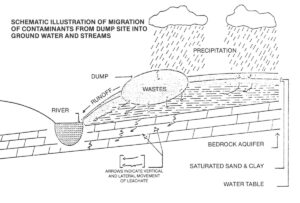

While the Ag Chem line hummed along, the workers ignorant of the hazards of DBCP, other problems were piling up in the form of pesticide wastes. Contaminated residues from the packaging operation and equipment cleaning water invaded the groundwater from an unlined pond in back of the plant. Half-empty pesticide containers and other solid wastes were dumped in a ditch nicknamed the ” boneyard. “

Occidental defends those methods with the standard argument put forth by the modern-day chemical industry: you can’t judge the practices of the past by today’s standards. Shipping containers and the big equipment vessels in which DBCP was manufactured were routinely detoxified with caustic soda and then washed down-a practice which was approved by the state. The company thought it was an effective method but, “in hindsight,” concedes vice president Rice, “that was not the best technology to use.”

Another misconception was the idea that organic chemical wastes would vaporize once they were put in the storage pond as wastewater – “go up rather than down, ” according to Rice -or else tie up to the soil particles if they did manage to get into the ground, thereby not contaminating the groundwater. It was a common error, one made by a number of other chemical companies during the 1950s and 1960s.

Not so common was the fact that company officials knew that pesticides residues were actually infiltrating the groundwater underneath the plant and threatening nearby home and irrigation water supplies.

“At its worst, Occidental’s conduct … amounted to willful and deliberate concealment of the company’s clandestine disposal of toxic wastes,” California’s attorneys argued in their lawsuit. “At best, it was maintenance of a no less cynical silence in the face of an obligation to speak, engaged in with the hope of escaping unnoticed.”

Company Memos

The state and federal governments claimed that Occidental knew that its pesticide wastes were contaminating the groundwater but kept silent about it. They argued that Occidental was making routine monthly reports on its non-pesticide wastes and ignoring the rest. Occidental contends that that’s all the letter of the law required it to do. Besides, the company argues, the state knew about our pesticide waste discharges for years and never complained.

If the case had gone to trial, the state might well have lost on technical grounds, except for one thing: the federal government had come into possession of hundreds of internal company documents which painstakingly chronicled the private thoughts and plans of Occidental officials as they were confronted over the years by increasingly complex and costly environmental rules. Although any company whose files were laid bare would likely suffer similar embarrassments, the Occidental memos are useful in this case in separating rhetoric from fact.

The memos were authored primarily by Robert Edson, a young, former Navy man with a degree in chemical engineering who became Occidental’s environmental coordinator at Lathrop in 1973. Edson still works for Occidental. He is described by company officials as sincere and genuinely concerned but perhaps too overzealous in his approach. “I think he really felt he needed to spur management to the ultimate to get his programs past,” said Occidental Petroleum Vice President Baeder.

The memos, excerpted here in chronological order, were obtained by the Securities & Exchange Commission during an investigation of Occidental Petroleum Corporation and by the House Commerce Subcommittee on Oversight, which held hearings on toxic waste disposal during the summer of 1979.

“Every person who decries the inflationary effect of regulating hazardous chemical waste disposal ought to direct his or her attention to this sequence of comments within this corporation,” said Representative Albert Gore Jr., (D-Tenn.), referring to the memos.

Occidental officials deplore the publicity given the memos and caution that they were taken out of a larger context. In one instance, Robert Edson, the company’s chief environmental officer, requested funds to install certain pollution controls; the funds had already been approved by the company president, according to Occidental Petroleum Vice President Baeder, when Edson’s memo was written. Company officials also say that Edson was unaware that the state knew that Occidental was in the pesticide business.

“He did not have knowledge of the state’s knowledge of our Ag Chem business,” says Occidental Chemical Vice President Mel Rice. Edson’s overall analysis of problems was “generally accurate,” Rice said, but he was “trying to sell an idea and made it a little dramatic, perhaps.”

Yet, several of the memos which were directed to corporate headquarters in Niagara Falls and Houston indicate that some Occidental officials were aware of the problems at Lathrop for at least several years before taking action to correct them.

April 29, 1975: Edson memo. “After more than two years of study of our pollution control problems versus the local county, state and federal laws, I have come to the conclusion that we must move promptly to stop all discharges of chemicals to the groundwater … The laws are extremely stringent about pesticides. We percolate … our pesticide wastes and I percent to 3 percent of our product to the ground in the form of production losses. To date, the water quality control people [state agency] do not know about our pesticide waste percolation.

Recently, water from our waste pond percolated into our neighbor’s field. His dog got in it, licked himself and died. Our laboratory records indicate that we are slowly contaminating all wells in our area and two of our own wells are contaminated to the point of being toxic to animals or humans. THIS IS A TIME BOMB THAT WE MUST DEFUSE. “

July 16, 1975: Memo from M.A. Stanek, the Lathropplant engineer, to W.A. Meyers, Occidental Chemical’s Assistant Controller, in Houston, Texas. “Should the water quality control regulatory agencies become aware of the fact that we percolate our pesticide wastes, they could justifiably close down our entire Ag Chem plant operation.”

June 25, 1976: Edson memo. “For years we have dumped wastewater containing pesticides and other Ag Chem products from washdown of equipment to a pond South West of our Plant and allowed the water to percolate through the soil to the groundwater. Our closest neighbor’s drinking water well is located less than 500 feet from the subject percolation pond and fortunately for the management of this company no pesticide has yet been detected in his water. I personally would not drink from his well.

Six years ago I had little knowledge of the damage that could be done with pesticides and I made a mistake which made quite an impression on me. I have two fish ponds in my backyard and in the spring of 1970 1 dumped about one cup of spider spray in one of these 200 gallon ponds to kill frogs. It killed the frogs so I proceeded to wash out the pond, cleaned it with caustic and acid, flushed it very thoroughly and filled it again. Fish died immediately. I continued flushing water through the pond for six years. Every summer I attempted to put fish in the pond and each year they lived a little longer, but eventually died.

… Most other organizations involved in pesticide handling have spent millions to solve their problems. No outsiders actually know what we do and there has been no government pressure on us, so we have held back trying to find out what to do within funds we have available.

… No one likes this project, most probably because very few people understand the total problem. Other companies’ solutions are so expensive we haven’t had anyone with enough nerve to even suggest that we follow their examples. I am quite certain that we can solve our problems for less than half of the cost of anyone else’s solution if we are allowed to proceed as we have begun.

…If we stop percolation now, I believe we may escape unnoticed. The next drop of pesticide that percolates to the ground is a management decision which I don’t feel we can afford. To date, we have been discharging more than 10,000 tons of waste water containing about 5 tons of pesticide per year to the ground. I believe that we have fooled around long enough and already overpressed our luck.”

July 19,1976: Internal memo reports that samples taken from the wastewater storage pond show high levels of Parathion contamination in soil.

September 3, 1976: Memo from Lathrop plant manager James Lindley to another executive. “It appears that the job of cleaning up the Ag Chem wastewater is going to take longer to solve than we had anticipated and regardless of the solution it will cost more money than we had anticipated. If someone else has discovered a simple, low-cost solution to the problem, then we need to know what they have done.”

September 29, 1976: Edson reported in this memo of the contamination of the irrigation and drinking wells of the company’s next door neighbor, a dairyfarmer who was not-told of the contamination for at least another year.

February 17,1977: Hand-typed memo from Joseph E. Baird, chief executive officer of Occidental Petroleum, to Donald Baeder, then president of Hooker Chemical Company. The memo was attached to a job interview request from a man who suggested that Occidental needed help in straightening out their environmental affairs and meeting new rules. “This is probably not the man that you need, and perhaps I need a high level fellow reporting directly on high concern matters. I do not think we can keep pushing this issue into the background. “

April 5, 1977: Edson memo. “The attached well data shows that we have destroyed the useability of several wells in our area. If we are to assure ourselves that we do not further deteriorate the groundwater in our area, we should continue the effort to stop percolation of water to the ground… I don’t believe the Water Quality Board [state agency] is even aware that we process pesticides.”

July 18,1978: Edson memo. “We have a number of situations where compliance with the letter of the law is questionable. Furthermore, the state people are sometimes not qualified to know what is and isn’t practicable. Yet their decisions could be binding and create difficult dilemmas. I recommend cleaning up our problems as much as possiblc prior to bringing state people into the problem. When the job we do looks good to them compared to other problems they have, I have found that they ignore us unless they receive complaints.

August 22, 1978: A detailed eight-page memo to corporate headquarters in Niagara Falls, New York which spelled out each waste disposal site on the property and what it contained. Pesticide wastes were reported at two sites, with the attached warning that they should be “considered hazardous. “

September 19, 1978: Edson memo. “We are continuously contaminating the groundwater around our plant. We are continually disposing of process water by percolation to the ground. We do not comply with California’s regulations for operating a disposal site.

September 29, 1978: Memo from Lathrop employee Mike Stoddard to Occidental Chemical Vice President Mel Rice. “I attended an environmental meeting at Niagara Falls this week where I discussed the water leaching problem… The Lathrop water problem can be summarized as follows:

Leaching of chemicals to groundwater has occurred as shown by well test data

The concentrations in the groundwater exceed water quality standards and we are in violation of groundwater regulations.

Potentially the chemicals could pose a health problem.

We are probably in violation of waste disposal regulations.

In 1967 we told the state we would eliminate our discharge. We have not done so.

April 11, 1980: Hooker President Donald Baeder in a speech to the Commonwealth Club of San Francisco. “We are justly proud of our environmental improvement record here in California at Lathrop. Contrary to what you may have heard or read, we have consistently reduced our discharges over the years…”

“Our guiding philosophy has been our determination to be a good neighbor-to comply fully with the letter and the spirit of the law and, where helpful, to go beyond the requirements of the law in order to assure that our operations create good neighbors.”

©1981 Cathy Trost

Cathy Trost, a reporter on leave from the Detroit Free Press, is investigating the evolution of toxic pollution policy in the U.S.