Self-care conferences drew 300 health professionals to New York City and 20 to Sun Valley, Idaho, this Fall. I attended both and left convinced that lay care is universal and that lay people should get more training if they want it. The New York conference was sponsored by the Institute for the Study of Human Knowledge; New Human Services Institute, Graduate school, City University of New York; and the Office of Urban Health Affairs, New York University Medical Center. Talks ranged from describing Chinese “street” doctors in communes after two weeks training in how Americans can control compulsive eating in Overeaters Anonymous.

In Sun Valley a month earlier 20 persons heard talks and swapped stories of getting self-care classes started and teaching them. The workshop was sponsored by Healthwise, Inc., of Boise, Idaho, a nonprofit organization which with a W. K. Kellogg grant has produced a textbook for self-care classes plus ten half-hour video tapes acted by professionals from a local TV station. This package limits itself to conservative, traditional medicine and includes a pamphlet to help people organize the course. Highlights of the conferences follow.

Self-Care: 19th Century Popular Health Movements

If someone ailing in 19th century America said: “Get me the family physician,” he or she would be passed a book by that name, probably kept on a shelf in the kitchen where everyone had access to it. The family physician was a book of the popular health movement, a domestic health guide, and not a live, walking doctor.

David S. Sobel, a 29-year-old medical student and fellow in the health policy program at the University of California medical school at San Francisco, was lead-off speaker to the 300 attending a two-day symposium on Self-Care for Health. He described the history of self-care.

“Families all across the country had health guides and one of the most popular was written by Dr. John C. Gunn in 1830 called Domestic Medicine or the Poor Man’s Friend,” said Sobel. Such books–and there were many–were introduced by health professionals interested in demystifying medicine. The learned, Gunn complained, used words ‘to conceal the naked poverty and bareness of the sciences. If the great mass of the people knew how much pains were taken by scientific men to throw dust in their eyes by the use of ridiculous and high-sounding terms, mankind would soon be undeceived as to the little difference that really exists between themselves and the very learned portion of the community.’”

Sobel said to this prose there is a current ring and like the self-care movement today it makes an appeal to return to common sense and to equip lay people with an ability to understand medicine. But Gunn’s practice was not much different from the orthodox medical use of emetics, bleeding and calomel. His attitude toward surgery was heroic. In Medicine Without Doctors, a book which gives an historical account of the period, it is said that any man with a firm hand and dexterity could amputate a limb. The book said among the most ardent champions of domestic self-care were the laymen, botanics, eclectics, homeopaths and hydropaths challenging the bleeding, blistering, and purging, for a safer, cheaper and surer way.

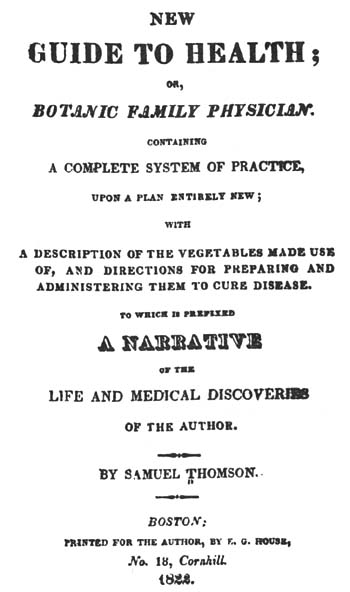

Samuel Thomson, a New Hampshire farmer who learned his botanic root and herb medicine from a female herbalist, coined the rallying cry of the popular revolt–”Everyman His Own Physician.” He published his New Guide to Health in 1822, charged people $20 to enroll in his Friendly Botanic Society and by 1840 had enlisted 100,000 subscribers. In states as diverse as Ohio and Mississippi half the citizens were curing themselves the Thomsonian way.

Title page of Samuel Thomson’s New Guide to Health, 1822, From Medicine without Doctors.

The movement reflected Jacksonian democracy and the importance of the common man, Sobel said. “There was a tremendous distrust and lack of faith in medical care,” he said. People complained against its high cost and elitism and preferred mutual aid and home remedies.

Sobel said the current shift to self-care is caused by the shift in diseases, the shift from pneumonia and other infectious diseases of 1900 to the major chronic and degenerative diseases–heart disease and cancer. “Where chronic diseases were once 30 per cent they are now 80 per cent of all diseases,” he said. “Half of the United States population has one or more chronic diseases and this requires a different model.”

Acute infectious diseases are episodic and get treatment aimed toward cure, he said.

But now we have a shift to the major diseases of civilization with more need for long term care. Cardiovascular disease leads with accidents following, then cancer, mental illness, respiratory illness, arthritis and rheumatism.

Health used to be thought of as an equivalent to medical care, he said. He quoted Thomas McKeown, a British professor of social medicine who is quoted regularly by self-care proponents. McKeown’s studies show that the fall in the death rate of TB has been only three per cent since the introduction of antibiotics. “The Netherlands doesn’t use antibiotics at all but has the lowest rate of TB,” said Sobel.

He said the decline was caused by improved nutrition, increased food supplies, and better hygienic conditions. The death rate in the U.S. in 1950 leveled off and has stopped dropping. “We’re saying medical care can’t do everything, so you pay attention to environment, behavior and lifestyle. We believe that we are ill and made well, but it is nearer to the truth that we are well and made ill by our behavior, and our food and our environment.”

Sobel said the economic domain believes self-care is a way to contain costs but that is open to debate. He said it is a part of a larger social movement of consumerism and self reliance and he referred to an Aetna insurance ad showing a patient bargaining with surgeons on price before his operation.

There is new impetus in self-care and a great variety of approaches, he continued, some focused on individual change and some on the orthodox medical model. Some are professionally dominated and others lay-controlled; some are packaged programs, others grass roots and spontaneous; some center on patient education and compliance and others on self-treatment and diagnosis, he said. Self-care is a primary form of health practice and has existed universally throughout history.

Sobel, before he transferred to California, was a medical student at Ann Arbor, Mich., where he became more interested in health than disease and wrote for Big Rock Candy Mountain. He also wrote a book Everyday Guide to Your Health (the title has a 19th century ring) and is coming out with a second: Health and Healing, Ancient and Modern. He feels the two most interesting areas in health are self-care and behavioral medicine (biofeedback and psychosomatic medicine). He is program director for The Institute for the Study of Human Knowledge, a co-sponsor of the conference.

Self-care education could take place in non-medical centers such as libraries. Lowell Levin, the next speaker from Yale University School of Medicine (associate professor of public health) made the library suggestion. Libraries are not tainted, he said, and people have a good feeling about them.

Levin said only three per cent of the people surveyed said they’d see the doctor on time in order to keep the family in good health, according to a Food and Drug Administration study in 1972. Two-thirds of all illness is cared for without any professional intervention and self-care is a universal first option.

He raised the question whether self-care education could become commercialized, whether some would want it to be licensed. (Insurance companies see it as a sort of driver’s education, he said).

“The definition of health care has become less rigid, less pristine and more tied with happiness,” Levin said. The more public knowledge of health there is the less disease control is necessary.

Chinese Street Doctors’ Work is Education and Prevention

Starvation and infectious diseases were the leading causes of death in Shanghai in 1940. Today life expectancy has risen from 40 years to the 70s and the leading killers are degenerative diseases–cancer, stroke and heart disease.

This is an observation by Dr. Victor W. Sidel, chairman of the department of social medicine at Montefiore Hospital, Albert Einstein College, Bronx, N.Y., who has made three trips to China to observe community health. He said that medicine had little to do with the change in Chinese life expectancy. The credit goes to better food, clothing, shelter and improved ways people work together. He said if there is a choice between preventive and therapeutic action the choice always goes to the preventive in China.

For background he explained China has four times the population of the U.S. with the same land area. Per capita income in China is $140 a year compared to $4,500 per capita in the U.S.

Sidel, speaking on the “Social Context of Self-care: U.S. and China” at the self-care symposium drew a picture of street “doctors,” women from the neighborhood educated for brief periods from two weeks to a month. They continue training as they work. “They are taught that nothing is beyond them,” said Sidel. He flashed a slide of two smiling women and they exuded confidence. They worked at the grass roots. The grass roots is regarded with more respect in China than in the U.S. Sidel said American bureaucrats, for example, speak of decentralizing from the top down to the bottom while the Chinese say “decentralize locally” giving increased emphasis to the local community.

The street doctors do little treatment. Their work is prevention and education. They produce homemade health education materials on how to get rid of pests and they encourage immunization. The materials include quotes from the late Chairman Mao: “We must call upon the masses to arise in the struggle against illiteracy, superstition and their bad hygienic habits.”

“It sounds more thrilling in the Chinese,” said Sidel. Thrilling or not China’s immunization rate is way above the U.S. where it has been dropping alarmingly. Measles immunization began in China in 1965 till today the country has a 98 per cent immunization rate. This compares with 60 per cent immunization in the U.S. going down to 30 per cent in poorer sections some of which have undergone measles epidemics as a result.

The famous barefoot doctors of China generally don’t wear shoes. The term is symbolic indicating that they are peasants remaining a part of the production team. The bare feet make them ready to work in rice paddies and show they are not a separate elite. Sidel spoke of one “barefoot” doctor who was first educated for three to six months. He then had three months training each year for seven years and still remains part of the commune work force.

He showed a slide of a hypertension clinic where a man was being interviewed by a western doctor and a Chinese medicine traditional doctor. The doctors were taking history while other waiting patients shared the man’s story. Sidel said someone on the tour asked what happens if the doctors disagree. The Chinese response was polite, that perhaps the Americans didn’t understand. Each doctor can explain his advice and if it is contradictory it is up to the patient to decide which advice to take.

“We began to worry where the question was coming from,” said Sidel as he flashed a slide of an ad published in the Journal of the American Medical Association showing an old American woman in a rocking chair. The ad read: “If she could choose her iron therapy, she would choose (brand X).”

“It makes you wonder why she can’t choose her iron therapy,” he said. Sidel said Chinese infants are 100 per cent breast fed and go daily to where the mother works with appropriate nursing breaks. At 1.5 years they are weaned to the cup and then can go to where either the father or mother works.

Sidel said that in kindergarten which covers ages three to seven children do not learn reading on the “Run, Jane, Run” level. Instead two six year olds recite from characters on the blackboard, the teacher turns them to face the class, smiles and repeats “It is correct” and they go back to their seats. What have they recited? — “United to win still greater victories.” Indoctrination begins early.

In an arithmetic lesson the problem is that in the morning the young pioneers collect five wheelbarrow loads of night soil (human excrement for fertilizer) to serve the commune. In the afternoon they collect another five. How many did they collect in all?

As you can see, said Sidel, arithmetic is only part of the lesson.

In China the commune chooses which street doctor or barefoot doctor or whatever person goes on to be trained in medical school. Most of the time commune members pick someone who has been serving the commune in health, according to Sidel.

In the U.S. in 1968 nine per cent of medical students came from families earning $5,000 a year or 25 per cent of the people and 20 per cent came from families earning $25,000 or more or 2 per cent of the population.

He recalled a sign in China that stressed four points. It read: “Eradicate the four pests. (At first, flies, mosquitoes, rats and sparrows, with the sparrows later being replaced in the list of public enemies by bedbugs). Develop good sanitation. Change old traditions. And reconstruct the world.” Change in health and change in the world are intertwined, Sidel noted. Health has a political dimension in China. Health has a political dimension in any country.

Here are some excerpts from Serve the People, the book he co-authored with his wife, Ruth, a psychiatric social worker.

At Shanghai Mental Hospital one of the psychiatrists told the Sidels: “It is not enough to have the doctors’ or nurses’ initiative. We need the patients’ initiative to work together against the disease.” Sidel observes: “This view of the patient’s relationship with his mental illness is a curious combination of individual responsibility and viewing his illness as an external enemy, a dual attitude that perhaps serves to maximize the patient’s efforts to fight his illness, while leaving him less guilt-ridden if he fails. Patients are not only expected to participate in their own care; they are also expected to help one another. The Shanghai Mental Hospital has a buddy system whereby the healthier patients who have been in the hospital longer help the newer, sicker patients to adjust to their surroundings and to understand their illness.”

Sidel on acupuncture: “In a dental clinic in Shanghai we observed anesthesia produced by finger pressure at acupuncture points without the use of needles. Pressure was applied for about one minute, a tooth was extracted, and the patient insisted–under our incredulous cross examination–that he had felt no pain. Many Western physicians remain skeptical and consider acupuncture to be a placebo or form of hypnosis, some even maintain it does not work at all and that those who report that it does have been duped. Insofar as this skepticism is based on the absence of a full causal or scientific explanation as opposed to the absence of controlled clinical trials it seems to us unjustified. The absence of a causal explanation does not mean that a technique does not work or that there are no direct physiological or pharmacological effects. We in the scientific West use aspirin to good effect enough though there are conflicting and yet unproven theories about how it works. Few would ascribe its effects to placebo or hypnotic mechanisms.”

On self-help, from an article “Beyond Coping” in Social Policy magazine: “Self-help in China functions within the context of attacking the exploiter rather than treating the exploited, of dealing on a social basis with many of the problems which we deal with on a medical basis. Self-help in China functions, particularly since the Cultural Revolution, within the context of specific societal attempts to deprofessionalize, demystify, and detechnologize as much of life as possible and to require professionals to function as an integral part of their communities rather than as a technological elite.”

“Male Medicine Dying Today” Feminist

Eighty per cent of paid health workers are women and most of the unpaid health workers–mothers–are women, too, a feminist writer and teacher told the symposium.

Barbara Ehrenreich, a teacher at the State University of New York at Old Westbury said that healing has been dominated by commercialization and male medicine, but that male medicine is dying today and has come to the end of an era. Before men took over healing, lay women healers, self-help and mutual aid were the major components of healing, she said.

“The act of healing now is not performed as a neighborly service but as a commodity. Traditional female healing operated as a network within families,” said Ehrenreich. “A disadvantage to treating healing as a commodity is that it becomes limited to those who can pay and results in unnecessary surgery such as hysterectomies and iatrogenesis (physician-caused illness),” she said.

It causes a hoarding of knowledge that becomes the private property of an elite with mystification of that knowledge being used to perpetuate that elite, she went on. The Carnegie Foundation’s Flexner Report, published in 1910, helped to create barriers limiting access to the medical profession by funding a few elite schools.

Ehrenreich writes in her book Witches, Midwives and Nurses:

“In its wake medical schools closed by the score, including six of America’s eight black medical schools and the majority of the ‘irregular’ schools which had been a haven for female students. Medicine was established once and for all as a branch of ‘higher learning, accessible only through lengthy and expensive university training.’”

She said the present system tends to “turn us into passive consumers” and that doctors will do anything to discredit lay information whether it comes from the Boston women’s collective handbook, Our Bodies, Ourselves, or from consulting other patients.

Women’s health care groups have pointed out the dangers of the birth control pill, medical distortions of childbirth, unnecessary surgery, dangers of DES, a hormone for miscarriages, and estrogen replacement in menopausal women.

“The women’s health movement has brought the information to the grass roots level,” she said. “There is skepticism of medicine because it has oversold itself, overdone the technological mystique and overpriced itself. And how the far right, its usual supporter, has broken with it over laetrile. The Harris poll shows Americans’ confidence in doctors has fallen 30 points in 10 years.”

Ehrenreich noted that Dr. John Knowles, president of the Rockefeller Foundation and former director of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, has said that because the health care system is in such a mess the only course for individuals is to take responsibility for themselves and to avoid disease.

She said she was disgusted by a new trend, co-opting self-care. Big business and forces in the Department of Health, Education and Welfare were using the language of self-help as a cover for letting the present system fall apart. This gives people a justification for dismantling services for the poor as fast as they can, saying such services are too expensive and they favor closedown of hospitals and clinics. The line, she said, is that health care is strictly an individual responsibility. “If you have lung cancer, well, it’s your own fault. You smoke. If you have heart disease you shouldn’t have eaten all those cheeseburgers. And for the cancer patient, cancer is psychosomatic. You’re probably sexually repressed.”

She said a Fall cover story in Forbes business magazine indicated that maybe big business should look into psychic healing and folk medicine for their employees, not because Forbes is into the counterculture, but because it sees it as cheaper. “So if someone has some cancer because of industrial chemicals, you tell him he ought to meditate. That’s the new line,” she said.

“Knowles and Forbes are saying we do not need any socially organized system of healing. We just need a whole lot of self-help with everyone taking care of his own health. Don’t smoke. Don’t eat fatty foods and presumably you should have the good sense not to live where there is pollution. If you do get sick there is all that cheap folk medicine out there. Shop around and you’ll find something.

“Now there is a grain of truth in this. It has something appealing. We do bear the responsibility for our own health. It is ultimately a conservative self-help strategy which is really profoundly dangerous because it means abandoning any kind of social responsibility. It should be called ‘Help Yourself Because Nobody Else Is Going To.”

She felt that recent self-improvement books such as How to Be Your Own Best Friend and Winning Through Intimidation exhibited “ruthless individualism.” “If you are poor or ill, the message is that it is your own fault and don’t come whining for help,” she said. “Health care is a community based service and when social services crumble the burden falls on women who will have to rebuild the system but not with lay healers.”

She said women can’t rely on a few liberal minded professionals but have to take direct action. An example is the group of 40 women who made an unannounced visit to a Tallahassee maternity ward. Several were arrested for criminal trespass. They had been checking conditions. Rebuilding, she said, doesn’t mean “turning loose with your own speculums and mirrors and saying you’re on your own.” She recalled an HEW official saying how wonderful the women’s self-care movement was because since clinics were being closed it would be especially good for poor women. “I was shocked,” she said. “The clinics are teaching women and exchanging information. They are doing a new kind of research…We can’t create health care in a society which is fundamentally uncaring for its members.”

‘I Learned I Wasn’t a Bad Person:’ Compulsive Overeater

Virginia Goldner, 32, professor of psychology at Goddard College, told how joining Overeaters Anonymous a year and a half ago changed her life. OA is one of the many self-help or mutual aid groups which have taken the Alcoholics Anonymous steps to recovery as a model. Instead of saying, “I am powerless over alcohol and my life has become unmanageable,” they substitute the word food.

Goldner, a dark haired woman with an engaging smile, said she had a unique chronic illness.

“I had no interest in food as a child. But between eight and 32 you couldn’t get me to stop. Food had extra meaning. It meant comfort, company, anger, not just nutrition. It is a progressive disease, just like diabetes and the older I got the fatter I got. I just got bigger and bigger. Every time I got big I got bigger than I got the last time. I had a distorted body image and only looked above the chin.”

She and a friend tried every psychological technique and therapy they could find but they kept on failing. Knowing why you gorged yourself or what certain impulses meant was no help. Finally they went to an OA meeting in New York City.

“It never occurred to me that self-help would help,” said Goldner. She is the author of Self-Help and Mutual Aid Networks in China but had not tried on herself what she had researched. “I was too ashamed.”

Her friend was five foot three and weighed 180; she was 5 foot six and weighed 185 1/2. “I was too ashamed until my first meeting June 5, 1976. The experience changed my life. The weight came off peacefully and it was a wonderful lesson in humility.”

She said she had expected to find that all people at her first meeting were fat but found that only 25 per cent of the members attending were obese. Fifty per cent looked ordinary and 25 per cent were thin. But each said that he or she was a compulsive eater and Goldner realized that compulsive eating is a state of mind, an attitude. “You can arrest it, but never cure it,” she said. “Weight doesn’t matter. You lose interest in whether you are big or little. How long can you go on struggling against the desire to eat compulsively? The thought of doing it for life is hard. A day at a time in little shifts is easier.”

She said she knows she is a compulsive eater with an addiction, “but I learned that I wasn’t a bad person.” She said there are many moralistic terms in dieting. She said she had two relapses in which she gained 10 pounds but she wasn’t ashamed because she knows she has a chronic eating disorder.

She said in Manhattan alone there may be up to eight meetings a day and that one could go to 90 meetings in 90 days, simply “gorging” on meetings if that is what someone needed.

She was critical of Weight Watchers, a profit making group, where the issue is weight watching. “That is all wrong. I don’t have a weight problem, but a problem with compulsion, a problem with food.”

She said the telephone is a tool. You get three numbers of other members to call if you are having problems. She said before she had no peace and was constantly miserable, but now with the power of the group she can get help from all the people in the New York area.

As in AA, OA members have sponsors. Each day Goldner had to plan what she was going to eat as many other diet groups do. “If I want to change from chicken to hamburger I call my sponsor. Because I know the group is there I am more peaceful about food. The group has saved my life. I’d be 100 pounds overweight without it. Everyday of my life I have an impulse to overeat. Insight into the problem is not enough. I go to meetings because I can’t deal with my problem alone.”

She recalled a man who had been bingeing on food. He came to a meeting and told what he had been doing and wept a lot. He didn’t stop his bingeing but he kept going to meetings, Goldner said, which indicated that he would get back on his feet eventually.

She said she used to feel snobbish toward people in the group with less education than she had. But then she realized that education levels made no difference. It was the power of the whole group that counted. When she became convinced that she was powerless over food and her life had become unmanageable she understood how the others could help her with her compulsion to eat–no matter how little education they had.

Other Anonymous Groups

You can’t be drunk at the same time you’re helping someone else. uch is the helper-therapy principle contained in the 12th step of Alcoholics Anonymous, the granddaddy (founded in 1935) of mutual aid groups.

Alan Gartner, Ph. D., a student of such groups and a professor, Center for Advanced Study in Education, graduate school and university center, City University of New York, told the New York symposium on self-care that when a helper sees someone else coping, he can see that person’s problems and solutions better.

He compared professional care with group care. Professionals rely upon systematic knowledge, keep a distance from the client, are objective, empathic (sic), standardized and careful to limit their time.

The group, on the other hand, uses practical experience, closeness and involvement, is subjective, identifies with the problem, is spontaneous and informal with unlimited time in comparison with the 50 minute therapy hour.

“I am not suggesting that one is better. Only that they are different,” said Gartner. “The groups tend to be parochial and help only those ‘just like us.’ They are concerned with the problem, not the cause.” He said AA is not at all concerned with the fact society is suffused with drug addiction or that half the auto fatalities are alcohol related. The group, after all, has only four to five per cent of the known alcoholics in society. AA members say simply: “We’re just a bunch of drunks helping each other to stay sober.”

Gartner began by ticking off the numerous groups which use anonymous in their name. They include Cancer Anonymous, Divorcees Anonymous, Dropouts Anonymous, Gamblers Anonymous, Migraines Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, Neurotics Anonymous, Overeaters Anonymous, Parents Anonymous, Psychotics Anonymous, Relatives Anonymous, Retirees Anonymous, Schizophrenics Anonymous, Smokers Anonymous, Suicide Anonymous, Youth Anonymous, Mistresses Anonymous and Depressives Anonymous.

He said a woman called to announce the formation of Depressives Anonymous and when he asked why she had organized the group she said: “Because I needed one.”

Other groups center on primary care such as women’s health. Then there is the category of persons living with the problem. They include Alanon for spouses of alcoholics and Alateen for children of alcoholics and Prison Children Anonymous. Well persons and people concerned with maintaining health join in health activation networks. There are also widow groups, Parents Without Partners and the Gray Panthers, active in legislative action for old people.

One woman called Gartner for help and when he told her about a group replied: “I don’t think I have the patience to listen to other people’s problems.” The group approach simply didn’t suit her, he said, which shows it is limited in whom it can help.

In this age, however, when 50 per cent of Americans have one or more chronic diseases, it is the self-help group which is most useful in helping people afflicted with chronic disease such as alcoholism and compulsive overeating.

Healthwise Prepares Teaching Package

A hobbyist has a pain from a blow on the thumb and uses a hot safety pin or paper clip to relieve the bloody swelling by making a hole through the nail.

A Seattle woman gives allergy shots to her children.

A student at the scene of an auto accident knows which victim to give what type of first aid.

A housewife with a burning sensation in her vagina learns to drink more water till it goes away.

Dr. Keith Sehnert, featured speaker who offered these examples at a two-day Western Self-Care Workshop in Sun Valley, Idaho, last Fall, said: “In all cases it is possible for them to be their own doctors sometimes.” His book is How to Be Your Own Doctor (Sometimes). He is an advocate of an activated patient network of people who have graduated from one of his courses — 16-session courses.

Healthwise, Inc., Boise, Idaho, sponsors of the workshop, drew about 20 persons from the Northwest including a nurse from Arizona who was starting a self-care course at Arizona State University’s graduate college of nursing.

Healthwise, with a grant from the W. K. Kellogg Foundation, has produced ten video tapes of a half hour each and a thick ring binder workbook using much of Sehnert’s material to make it easy for someone to set up and teach a self-care course.

Lowell Levin, self-care promoter from the Yale University School of Medicine, told me he didn’t like packaged courses because they don’t allow any variation of input from the students. “Their course is so organized they even tell you when to have a coffee break,” he said.

He is right about the coffee break. The instructor’s guide, for example, indicates a stretch break starting at 56 minutes into the two-hour class and finishing precisely at one minute past the hour. A Healthwise videotape on injuries, put together in conjunction with a local television station showed how ice should always be used after an injury. It suggested the householder keep ice frozen in paper cups at all times so in case of burns or cuts the paper could be peeled and the ice comfortably held to the wound. It demonstrated punching a hot paper clip through a nail and using a flashlight to attract and mineral oil to float a bug from an ear.

Isaac C. Ferguson, manager of health services for the Mormon Church, said that no matter how he tried to recruit candidates for self-care courses they always ran 75 per cent women and 29 per cent men, a breakdown others experienced, too. “In contrast emergency care classes seem to get the hairy-chested group,” said Ferguson.

Sehnert said recruitment of students for self-care classes takes persistence. “The first class is always a toughie,” he said. But they’re worth it and save patients visits to the doctor and the emergency room and doctors from unnecessary patient phone calls. Sehnert said he found that the coping skills and nutrition sections of courses were better taught by lay people than by psychiatrists and nutritionists. “They are so trapped in jargon that we didn’t like to use them,” he said. Most classes in rural areas are underserved by doctors or served only by nurse practitioners. Thomas Ferguson, editor of Medical Self-Care magazine, said he found many programs in Minnesota, Maine and California, but least interest in Boston, New York and Washington, D.C. because of greater doctor supply.

Sehnert, who has moved from Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., to take a job with a consulting firm, InterStudy, outside Minneapolis, said he saw a big future for health promotion in industry. He said that TRW, a Cleveland firm in high technology, transportation and telecommunications, had health costs up to $65 million last year and is groaning under the impact. “In the next several years health costs in industry are going to be the big focus,” he said. At TRW one-third of the costs involve employees in the plant with dependents’ costs coming to 60 per cent and retired workers ten per cent. Companies are starting to try health activation and weight reduction to cut costs and reduce sick time, he said.

Sehnert doesn’t think the newly formed U.S. Bureau of Health Education in Atlanta will have much effect but urged self-care people to remember there is money in the Department of Agriculture, Housing and Urban Development and private foundations. Health, Education and Welfare isn’t the only source of support, he said.

Others speaking at the workshop included Richard Grant, director, Rural Family and Self-Help Education Project, Redmond, Oregon; Donald W. Kemper, executive director, Healthwise; and Gary Steinbach, Sun Valley Executive Health Institute, Sun Valley. Steinbach outlined his institute’s four-day program which costs $1195 a couple. It has graduated 300 people since it opened in June 1976, covering everything from how to eat from a restaurant menu and still get nutrition, to a grip test and a stress EKG.

Commentary

The words that ring for me when I think of self-care are community and group, not individual. The Chinese have had great success getting people to work together in sanitation fighting the four pests: flies, mosquitoes, rats and sparrows. Their key word is prevention. Immunization shots there are way ahead of the U.S. They approach self-care on a community basis. In some rural areas in the West I was told that a graduate of a self-care course is regarded as a special helper to the nurse-practitioner. That person becomes known and used by the community and his/her main task is education as is the task of the street doctors in the communes.

I recall the black community of West Garfield Park in Chicago which was trying to become more of a community so that it could be healthier. It is clear to me that health is political. The fact that 40 per cent of the $140 billion the U.S. spent on health last year went to hospitals is no accident. And many people were hospitalized not because they needed to be but only to pick up benefits because that is the way the benefit plans were written.

I feel good health is a by-product of a healthy community. You don’t seek the health outright all the time. You concentrate on the community and the health follows. There is a danger that self-care classes by encouraging everyone to be his own paramedic will encourage us to be so acutely aware of our health that it will be boring.

I find the point intriguing that the shift from infectious to chronic diseases makes an excellent entry point for self-care. A heart patient who is sent home after an attack is not under doctor’s care, he’s under his own care and if he can join a group of others recovering from heart attacks he will have a better chance. Overeating is certainly better handled through group treatment of compulsive eating than by diet pills. Lay men and women supporting one another makes sense.

As Tom Ferguson of Inverness, Calif. said in Sun Valley: “Health is not something to be delivered but something to be encouraged.” To me the word delivery recalls missile system delivery. The word delivery has a pushy, authoritarian quality to it. Dr. Victor Sidel who lectured on China concludes in his book that folk and traditional medical practices accepted by many citizens are “ignored or ridiculed by medical professionals, rather than used together with scientific techniques to help those who are ill.” He urges that preventive medicine be primary and that health care be relevant, using folk medicine and traditional techniques where appropriate. I was fascinated by Sidel’s stories of China and am eager to find out how well he has been able to adapt Chinese methods in the Bronx. I also want to go to an Overeater’s Anonymous meeting. I have added pounds, and I would like to experience a group’s support.

I remember what John KcKnight of Northwestern University said about community and health: that justice, equity and a shared belief system are the keys to a healthy community, that people like the Mennonites enjoy good health as a side effect of their lifestyle. That appeals to me. I am not wanting to be a Mennonite but I am seeking a closer community and neighborhood in my own life as a context for individual self-care.

Received in New York on January 27, 1978

©1978 Phil Weld, Jr.

Phil Weld, Jr. is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from the Lawrence Eagle-Tribune. His fellowship subject is the role of self-care in health: a look at prevention, patient education and patient power in the U.S. and Canada. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Weld as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation and to the Lawrence Eagle-Tribune. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.