Self-care, self-health, self-repair and self-healing books proliferate in the health sections of paperback bookstores.

One self-care advocate, a professor of public health at Yale University School of Medicine, said he had counted 600 titles recently. In 1972 he had been unable to find a publisher for an article on the subject.

A Boston newspaper survey showed that self-help books ranked side by side in popularity with books on meditation and making love how-to-do-its such as the Joy of Sex.

Andrew Weil, a renegade physician who has spent five years studying alternate ways of healing, writes in the May/June issue of Quest magazine that people are fed up with the medical establishment and are forming a new popular health movement. Its growth recalls the 1830s movement that shook American medicine, he wrote.

This April, I took a leave from my newspaper for a year to explore this growing interest in self-care in the United States and Canada and to take a look at prevention, patient education and patient power.

A pediatrician in New York City at Health PAC (Policy Advisory Center) questioned me on whether I defined self-care in terms of the women’s movement.

He felt the term was mainly used in the women’s movement and that it was anti-professional, interested in group education and non-pharmaceutical. The best known self-care tip was yogurt for vaginal infection, he said, but there was no known medical study to say whether it was effective.

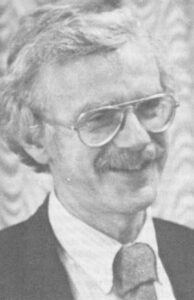

Lowell S. Levin, public health professor at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., has logged 200,000 air miles in the last six months giving weekly lectures on self-care. He estimates that 70 to 85 per cent of medical care is provided by lay persons.

“The government is trying to stop this,” he said. “In fact the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) has called it ‘rampant empiricism’ when in fact the health care system wouldn’t last six hours without self-care.”

Another leader in the self-care field is Keith W. Sehnert, M.D., author of How to be Your Own Doctor (Sometimes). His course for activated patients (he is the Director of the Center for Continuing Health Education at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.) is designed to put the patient behind the stethoscope, that symbol of medical authority. His classes get them free from local hospital coronary care units which use $2 disposable stethoscopes.

The rest of the activated patient’s black bag includes a good thermometer, high-intensity penlight, tongue depressor blades, $20 blood pressure cuffs (properly called sphygmomanometers) and otoscopes for examining ears. Sehnert estimates the total cost of the kit from $40 to $75.

He related the story of one pediatrician who was shocked that the mother of the child he was examining had an otoscope. “A medical student has to look into hundreds of ears before he really knows what he’s seeing,” he declared. “How can you believe that an evening’s training qualifies you to use an otoscope correctly?”

“Undismayed, my A.P. (Activated Patient) explained coolly, ‘Doctor, I am not a physician. I do not make a diagnosis. I merely report what I see, and then await my doctor’s instructions,” Sehnert wrote.

And so the self-help medicine movement is bound to threaten some doctors and others of the 4.7 million persons directly employed by the health care delivery system which totaled an estimated $138 billion spent for health last year or 8.7 per cent of the gross national product.

Sehnert believes that patient education of the sort he prescribes could go far toward reducing those costs and keeping people out of hospitals.

Levin notes that hospitals generally resist patient medication. He said he has the minutes of a meeting quoting one New England hospital administrator as questioning the advisability of patient education because he feared it was likely to reduce in-patient income.

He also said that at one point the primary makers of blood pressure cuffs designed them so that the patient couldn’t read his own level and therefore only a physician or health professional would be able to take blood pressure.

Dr. William Stason, a cardiologist at Harvard School of Public Health, treats a lot of his patients for hypertension (high blood pressure). Some of them are participating in a study and take the blood pressure cuff home and log readings at specified times.

To me the blood pressure cuff has always been a symbol of medical help and I had not thought of administering it to myself until I saw Dr. Stason pull one out of his file drawer and start to pump it up.

A jogger of seven years now doing about four miles a morning, he also does TM (transcendental meditation). “That two cups of coffee this morning did me in,” he said as he took his pulse. I am a jogger and my pulse is running 60 when it is usually 50,” he said.

I began my search into self-care by using the Harvard School of Public Health as a base. I first interviewed Dr. William Bicknell, former Massachusetts Commissioner of Public Health, who made a name in my newspaper community of Lawrence by closing a local chronic disease hospital called the Bessie Burke Memorial. The city-run hospital required a certificate of need from the state (jargon for approval of building and renovation plans exceeding $100,000). Supporters of the hospital were furious at Bicknell. He does consulting now and has an office at the School of Public Health. When I told him of the reaction he said:

“Hospitals have great charisma, more than people think. Whenever they get closed, people react.”

Bicknell was a doctor in the Peace Corps in Ethiopia and he said that volunteers were two days away from medical help so they would all be trained in self-care to use antibiotics, treat nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, avoid alligators while swimming and bus accidents while traveling by simply checking out the tires and size of the load before getting on. Bus accidents in Ethiopia are much greater public health hazards than in the U.S., he said.

“We have discouraged people from self-care,” he said. “Why can’t a mother swab a kid’s throat when the fever is over 102 and take a throat culture and send it off to the lab in the morning?”

“With a swab, simply a Q-tip with a long handle, anybody can do a throat culture. It can be taught to a high school age lab technician in five minutes. Then the mother could be administering the penicillin without checking with the doctor first and call a nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant. It would be an alternative to visiting the emergency room and it costs less and the

child would be miserable for a shorter period of time.”

Bicknell doubted it would be accepted. “It would be viewed as radical by the medical establishment. It poses an income threat but there is no medical reason against doing it.”

Self-care, he concluded requires a more informed consumer. “Massachusetts is one of the worst places to do self-care because there are so many doctors,” he said.

The week after I talked to Bicknell I described my 11-year old daughter’s sore throat to our pediatrician and he said to bring her in for a throat culture. I tested Bicknell’s idea on the nurse who swabbed the back of Sarah’s throat in a moment. She told me that she didn’t think parents would get the swab deep enough in the throat. “You have to get the gag reflex,” she said, “and if you don’t hit the right spot you waste time on the culture.”

Tell that to Bicknell, I thought.

When I reached Levin I felt I had come to a touchstone of my subject and that he would provide leads to others so that I could get a varied look at the movement.

Levin’s book Self-Care: Lay Initiatives in Health written along with Alfred H. Katz and Erik Holst gives an academic overview of self-care arising from the August 1975 International Symposium on the Role of the Individual in Primary Health Care held in Copenhagen, Denmark.

One of the participating 29 scholars from four European countries, Israel and the U.S., was Victor Fuchs (author of Who Shall Live?). He wrote:

“By changing institutions and creating new programs we can make medical care more accessible and deliver it more efficiently, but the greatest potential for improving health lies in what we do and don’t do for and to ourselves. The choice is ours.”

After graduation from Harvard School of Public Health Levin started at the University of Vermont in a new and novel department of preventive medicine. “Such departments were unusual then (1957) and my job was to assist a team including a sociologist to help underserved areas of the state.”

Levin said he came to the work equipped with the “myths” that disease is bad and health is good, that health care meant doctor care and that the more medical care you have the more health you have.

He described a typical Vermont town which said it needed a doctor, basically for emergencies once or twice a year and childbirth. The town was willing to build a young physician a building which would enable him to cut his fees. Nearest medical treatment was 15 miles away. Levin didn’t believe the town needed a doctor and if it got one the doctor would stagnate from lack of work. “The trend away from general practice was in full swing,” he said.

He then visited East Africa where he saw medical assistants with less than 18 months training helping to remove cataracts. At the same time at home there were studies examining use of physician extenders (jargon for physician’s assistants, paramedics) as well as pediatric nurse practitioners.

Also Levin said that Thomas McKeown, a researcher, was coming up with studies which showed that major diseases had subsided before medical treatment. McKeown concluded that hygiene, water supply, nutrition and natural immunity in the host were bigger factors than medical treatment in quelling disease. “Only in the case of smallpox was there marginal effect,” Levin said.

“The myths are that an increase in professional care results in increased health and that medical care is a positive goa1 said Levin. “Instead one out of five patients leaves a hospital with a disease he didn’t come in with. People become psychologically dependent on doctors. Hospitals are unsafe and unsanitary. Medical care can be effective, not effective and negatively effective.”

Levin, 49, said he began to realize the limits of medicine and that other social needs were far more important than health needs and that investing more in the health care system was not going to produce more health.

For him health is not the goal, nor disease the evil. “The goal is happiness,” he said.

“We need education education, not health education for specific protection against disease,” he said, explaining that educated persons know how to make choices and avoid bad situations whereas the uneducated poor stay put and suffer through.

The book which best represents his philosophy is Brazilian Paulo Freire’s The Pedagogy of the Oppressed. The paperback has sold a half million copies in the U.S.–in translation from the Portuguese. It explains Freire’s theory of the education of illiterates, especially adults, based on the conviction that every human being, no matter how “ignorant” is capable of encountering his world.

(Dr. John H. Knowles, president of the Rockefeller Foundation, estimates there are 25 million poor Americans whose nutritional and medical needs go unmet).

Prof. Levin said that half the population has one or more chronic diseases requiring self-care. “The job is not to stamp out disease but to stamp out ignorance and to educate people to understand the risks they choose,” he said.

“Life is a process of selecting one’s cause of death and society needs to help people make choices. I smoke a pipe and risk tongue cancer but no cigarettes because I don’t want to risk lung cancer. I drink and run the risk of cirrhosis, but I am a careful driver and use my seat belt.”

“In Britain they don’t require safety glass on windshields which is a case of not knowing the risks. The role of health education is to give knowledge to make decisions.”

Levin urges lay people to remember that medicine is not a science, but is largely judgmental. (For example, a while back it was bad for new mothers to exercise, and now it is good). “The half-life of a health fact is five years,” said Levin.

Levin said when he mentioned basic self-care he meant care for arthritis, heart disease (diet and exercise). “It is said that after a heart attack a person is under physician’s care when in fact he is under his own care with that physician’s guidance.”

In his book he writes that some professionals say “self-care in health is folk practice, culture-bound and indigenous, riddled with absurd and ineffectual remedies, rampantly empirical, contributing on occasion to unnecessary delays in seeking professional care and often implicated in the failure of lay persons to follow prescribed medical regimens.”

At this moment I recall my most basic piece of folk medicine learned from my mother–how to fix an ingrown big toenail. You may laugh, but they get people with ingrown toenails at Lawrence General Hospital along with the rest of the 70 per cent non-emergency visits who never learned what my mother taught me. The first lesson is to prevent the ingrown toenail by cutting the nail straight. If you miss and get it at angle and it starts to hurt, cut a small “V” at the top to lessen the pressure on the sides. I’ve used that many times, and it works.

Levin as a public health epidemiologist regards doctors’ offices and hospitals the way doctors regard the mortuary–they are places he wants to keep people out of.

“Five per cent of hospital admissions suffer doctor-medicated error. The medication error in a hospital is enormous. Doctors should be prohibited from writing prescriptions in a hospital and let a clinical pharmacist do it instead.”

He said doctors’ prescriptions are all right in their offices where the average physician sticks to about 25 drugs he is familiar with on dosage and side effects. Levin went on:

“Hospitals are running out of patients,” he said. “Births are dropping and occupancy rates of maternity units are running 40 to 50 per cent.

“Total they are running about 80 per cent . Break even is 90 per cent. So the full bed is subsidizing the empties.”

Part of the self-care stratagem includes assertiveness training for the patient. “Passive, frightened patients have slower recovery rates,” he said. “You have to protect yourself against the assault of the system. If every patient complied with doctors’ orders you would have a death rate you wouldn’t believe.”

Levin deplored the fact that doctors allow patients to over-medicate themselves. “Twenty-three and a half drugs are in the average family medicine cabinet and 40 per cent of the drugs issued are written up by the patients themselves when they call up and say, ‘Gee Doc, I think I need a little…’ and the physician writes the prescription.”

“It’s a scandalous state of affairs. I am not anti-doctor, but I am anti-myth and anti-ignorance.”

“Hospitals are necessary but undesirable. They are houses of social casualty, like jails. You don’t improve them but you try to get rid of them. And doctors. Who wants a doctor? We don’t want doctors, but we may need them.”

Levin writes that “recovery from many morbid conditions and the maintenance of health depend on the ‘patient’ assuming a great measure of responsibility for himself…Psychologically, self-care in health also may be viewed as a natural consequence of the wish of patients and their families to do something constructive when illness occurs instead of remaining passive. As we have seen, self-care is important, sometimes indispensable in preventing, treating or stabilizing some of the most prevalent and debilitating current illnesses. Even when self-care may not be appropriate, or when patients and their families wish to be completely passive and dependent, studies have shown that greater communication and mutual understanding between physician and patient facilitates patient recovery.”

Activated patient courses which I would like to explore in addition to those run by Dr. Sehnert at Georgetown University, are offered from the University of Maine in Augusta by Peter Durand with others in Hartford, Conn., and Boise, Idaho, Levin said.

“We’ll teach anything they want to know and they have to say how they want it to be taught and give an evaluation of how it worked for them,” said Levin. Levin learned that one woman who had signed up was eager to have her daughter like her more. If Levin didn’t help her accomplish that the course would have been a failure for her, Levin said. He said the daughter regarded her as someone who never did anything around the house. The mother wanted to learn to be the chief health care person in the family, a person of respect.

“Self-care is a freedom producing enterprise which is not demanding allegiance to any-behavior but gives people a chance to live,” Levin said.

Levin is looking for an engineer to help him transform bathrooms into home-health suites with a home dental drill, more efficient water supply outlets and a special seating arrangement so that a woman could give herself a vaginal exam. “I want to build in facilities for people to do their own care privately,” he said. He added:

“My aim is to help reduce the number of hospitals and to see medical schools drop to 10 per cent of their present enrollment.”

Levin listed others who shared the self-care concept. They include:

Irving Zola, professor of sociology at Brandeis University who lectures on the “healthist” society, John McKnight, professor of urban affairs at Northwestern University who talks about the “medicalization of politics,” John McKinlay, sociologist at Boston University, Lois Pratt,. professor of sociology at Jersey City State College, Jersey City, N.J., Nancy Milio, associate dean of nursing, University of North Carolina, and Ivan Illich, author of Medical Nemesis: The Expropriation of Health. Levin said Illich’s book “sent a roto rooter through the health care establishment.” It is a polemic which states that modern medicine is a threat to health.

In the coming months of my fellowship I want to probe the self-care concept further and read everything I can about it, including Medical Self-Care Magazine: Access to Medical Tools edited in Inverness, CA.

I want to know what the funding powers in the National Institute of Health and other parts of the federal government have to say about it. Surely there is more regard for people taking charge of their own disease other than calling the act “rampant empiricism.”

I do not see the movement as anti-doctor, but I do see it putting the physician in a different place from TV’s Marcus Welby.

“A doctor is at best a colleague, not a miracle-worker,” writes Richard Grossman, a consultant to the Institute of Health Team Development at Montefiore Hospital in New York.

Further I would like to see how Canada compares with us. Prof. Levin pronounces Canada as “light years ahead of this country in health;” Sen. Edward Kennedy regards Canada way ahead of the U.S.

I also want to know if the self-care concept can help change the lifestyles and behavior of Americans (driving, eating, drug taking, drinking, and exercise habits).

As Leon White, Ph.D. at Harvard School of Public Health, said: “The major problem with changing lifestyles for a healthy people is that it is not clear that the public’s goal is to live as long and as healthy a life as we may think they want to.”

In Mill Valley, California, Dr. John Travis runs a Wellness Resource Center where there are no patients, only clients. Note the first part of his client’s agreement: “As a client, I acknowledge full responsibility for myself. I realize that my health state (me) is a manifestation of my habits, actions and behavior.” I want to visit that center.

In short I have plenty to do on the job on a subject that touches everyone. And I find almost everyone has a suggestion of someone to talk to or something to read.

I invite my readers to write or call me with suggestions at 105 Lovett St., Beverly, MA 01915, 617-927-1898.

Received in New York on May 2, 1977.

©1977 Philip Weld, Jr.

Philip Weld, Jr. is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from the Lawrence Eagle-Tribune. His fellowship subject is the role of self-care in health: a look at prevention, patient education and patient power in the U.S. and Canada. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Weld as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation and to the Lawrence Eagle-Tribune. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.