John L. McKnight is a friend of Ivan Illich. He collaborated with him on Medical Nemesis, the book that describes the medical establishment as causing sickness. He pronounces Illich’s first name softly -“Eevahn.”

McKnight told how his Center for Urban Affairs at Northwestern had helped West Garfield Park, one of the toughest black ghettos in the country on Chicago’s west side, meet its health problems in an Illich-like manner. The area was in flames during rioting before and after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968.

“It’s okay to say that health is a problem and that crime is a problem, but it is a big mistake to think that more medical care and more police will improve matters,” said McKnight. “What you have is a collapsed community. Health and security are outcomes of things other than more police and more doctors. They are the result of a just community, not the result of resource inputs.”

He said volunteers and staff of the Christian Action Ministry checked the local Garfield Park Community hospital and found the top seven reasons for emergency room visits were personal attacks, traffic accidents, respiratory infections, alcohol and other drug abuse, falls, dog bites, and personality disorders.

“Doctors can’t help with these problems,” said McKnight. “Medicine makes each problem individual. Doctors won’t fix a street that is causing auto accidents, but they will give you a lot of doctors to fix the broken bones from the street.” The area recorded 14,000 pedestrian auto accidents–among 80,000 or 3.5 per block per year.

McKnight said that in medical terms justice means we need more doctors. “The medical model would say increase medical resources, but the second model of analysis finds the determinates of ill health, gets a set of interventions, and the input is community action. It is a political issue.”

He said he had given some thought to the Mennonites in Ohio where anyone who died before 90 died young. His analysis was that the Mennonites had good work, a shared belief system and that good health was a side effect of the first two.

“Justice, equity and a mutual system of belief are the keys to a healthy community,” he said.

At one point during McKnight’s account Maggie Kuhn who had listened as intently as I did commented that separation of people by age hurts a community and causes a health problem. She particularly criticized communities such as Sun City, Arizona, and Leisure Park at Laguna Beach, Calif., and called them “agist.” Kuhn lives in Philadelphia with three young people, and they are participating in a decision as to whether one of them will have an abortion or not.

A week later I visited Clay H. Collier, director of health action at CAM (Christian Action Ministry), 3932 W. Madison St., Chicago. Collier, 28, is a graduate of CAM’s second-chance academy eight years ago and the University of Montana at Missoula in Philosophy and history of science.

He had come from watering the garden on CAM’s third story roof as I arrived. When we began talking in a law library conference room on the second floor below the garden, there was a significant dripping leak. Collier put a wastebasket under the drip, and I thought how quaint it was to have a ghetto garden leaking into a law library and how much it could mean to the people.

Collier reviewed CAM’s efforts in health action since its linkup with Northwesterm in 1974.

Health of the people in cities is largely determined by income, jobs, environment and what people do for themselves, he said. Doctors could patch people up but they could do nothing about the causes of major health problems like auto accidents, alcohol and other drug abuse and dog bites.

Collier said the first thing they tried to find out was why people were in the hospital and the first problem was to decode the records. It’s nobody’s job to list systematically causes of hospitalization because the records are treatment oriented rather than cause oriented. They don’t say broken leg in auto accident at Madison and Pulaski, or laceration from dog bite and list the address.

Collier said they had to get a transportation department study, a three-inch thick computer printout with an elaborate coding system for accidents, that was hard to read. Finally they plotted the accidents involving 7,000 persons in cluster areas on a grid. With that information they went to their own Health and Safety Advisory board where people identified the cluster areas as having misplaced signs, pot holes, blind entrances into parking lots, or overflow of expressway traffic into small arteries.

“We took the information to the department of streets, department of transportation and the two aldermen,” he said. The machinery of government began to pay attention to the trouble spots because the neighborhood had good solid information. Aldermen Leroy Cross and Jimmy Washington “felt we were helping them do their jobs.” said Collier. “There had not been much constituency in their wards previously.”

Volunteers got schools involved on the auto-pedestrian accidents and asked them to train kids to cross streets more safely.

Next on the list were animal bites, some rats but mostly dogs who roamed areas in wild packs, living in abandoned housing and sheds (80 per cent of the industry has left the area). “Old people were fearful to go outside and many kids got bitten,” said Collier. “We went to the Austin district police to get the information we needed, names, bites reported, time and location.”

The police who had undergone some bad publicity involving several of their number convicted of taking bribes from a local tavern owner, were wary of the community asking too much.

“First they said they couldn’t let any of our people in their files. We were calling them daily. Then the person we were talking to went on vacation. Finally they agreed to do it themselves after two months,” said Collier. They found a four block area with 250 bites reported, some of them deep cuts requiring stitches.

“It cost $60 in police time to investigate a dog bite each time. You would think they’d see value in citizen work to clean up the packs and prevent bites.” He said the animal care section of the police department was understaffed with poor morale because it was considered the worst assignment.

McKnight had told me earlier that it is more important to strengthen the community than to catch wild dogs. In other words if you pick up the dogs without having the community participate you haven’t helped the problem.

Collier said CAM put up a $5 reward for capture of a dog. In two weeks it got 68 dogs and by the fifth week 148. “Spirit was great. Kids caught dogs with morsels of food and brought them in bags, tied them with clothesline and buckled them with belts around the neck,” he said. They were scrawny animals and about four-fifths of them were destroyed.

He said the people catching the dogs who were 12 to 30 years old called the police animal care unit themselves and learned they could depend on the city. “The city works by pressure and the community was raising its awareness to that. We told people they could do something for themselves and that we were willing to reward them. There was a spirit of helping themselves,” said Collier.

The greenhouse on the roof of the CAM building is a symbol of community self-help as well as a source of everything from tomatoes and collard greens to green peppers and cucumbers. Vegetables grow hydroponically, using vermiculite and perlite, pulverized lava and mica, instead of soil. They are fed from a barrel of water laced daily with minerals and plant food.

McKinley Shaw, garden caretaker, was removing dead leaves from the tomato plants. He told me he liked the work. Collier said the greenhouse was a $5,000 investment to pay for itself in half a year and that he could see 300 other rooftop greenhouses in the community within 10 years. He said hydroponic farming met a need for fresh food because many supermarkets have left the area along with the industry. He said the greenhouse is 880 square feet and produces 12 to 15 pounds of vegetables a square foot per year with young and old working together. Unemployment rate is 40 per cent for youth and 28 per cent for adults.

Ask Collier what he feels are the neighborhood’s real health problems and he says joblessness for young people which can result in personality disorder, heatless housing with dripping water that produces high respiratory infection, garbage in alleys where rats abound. He said 10.6 per cent of the emergency visits to the hospitals were the result of falls.

“We want to find out what was the environment of the fall,” he said. “We don’t need a new bed to rest a broken hip on. We need a new lighted corridor to walk through safely.”

Some of CAM members have gotten appointed to hospital boards where other board members are eager to help by offering the neighborhood use of a $500,000 brain scanner or more hospital beds. “They are asking the wrong questions,” Collier said, “and don’t understand neighborhood health problems.”

“If you could raise the economy by $3,000 a person the level of health would go up 15 per cent,” said Collier. “Improved housing affects self-esteem and mental health. Many here feel no purpose in life and lack self-worth.”

He said CAM has the novel idea of doing fish farming in a pool, unused for years because of lack of recreation funds, growing bean sprouts in the basement and recycling energy and methane from waste. “In the 1950s and 1960s professionals came into the ghetto telling people what to do,” said Collier.

He feels residents are more involved in community self-help such as the wild dog collecting, the gardening and dealing with the hospitals on accident statistics and subsequently pressuring of the aldermen and the department of streets.

Dog bites and traffic accidents are down. One hopes that he and McKnight are correct in seeking community change for health because it could mean a model for collective self-care in other parts of the country.

The W. K. Kellogg Foundation of Battle Creek, Mich. turned down a $70,000 application from CAM. They liked the idea, according to Collier, but rejected it because CAM was too political, they said. Applying local pressure in a political way is central to CAM’s philosophy.

Swami Rama and the Nose

“You can’t miss the institute,” said Marilyn Preston, an eager reporter of the “new medicine” for the Chicago Tribune’s feature section. “You must see Swami Rama.”

Swami Rama is the yogi, she explained, who stopped his heart for 16.2 seconds at the Menninger Foundation in 1970. It must be said that he stopped his heart from pumping blood because he had so much control over his autonomic nervous system that he could cause an “atrial flutter” and a heart beat averaging 316 beats per minute. ” He made western medicine aware of eastern medicine.”

So I was off to Glenview, a north suburb of Chicago, to visit the Himalayan Institute. I arrived at the train station three quarters of an hour before my 7:15 p.m. appointment with Swamiji as he is called. I wanted to ask him about self-care, a subject I felt anyone working so long on self-care would warm to. The cab I called was late. I called the institute. They said Swami Rama was waiting. I called the cab number again as I don’t like to keep swamis waiting. The dispatcher said, “Shortly” and 20 minutes later one arrived. I had been pacing the platform figuring that a good yogi waits with tranquility.

The delay was okay. Swami Rama’s secretary Sam Skriti (an American who has taken an Indian name) ushered me into a lecture on the nose, a series on the science of breathing by a psychiatrist and the physician at the institute, Dr. Rudolph M. Ballentine, Jr. Sam Skriti said Swamiji would be available afterwards for a brief visit.

When I entered the lecture room Dr. Ballentine, a lithe red-bearded man, was sinuously imitating the waving movement of the cilia, the little tiny hairs inside the nose and bronchial tubes which “keep the blanket of mucus moving.”

His drawing on the blackboard showed how the confirmation of the internal nose with its sharp turns deflects air as it enters and before it reaches the lungs. Each of us has a unique internal nose as well as external nose. Big noses are for heating cold air. Short noses are for hot climates.

He mentioned that noses have erectile tissue just like the sex organs and can become engorged with blood. Witness “honeymoon” nose, he said. Few Americans including medical students are aware of the difference in breathing with the right nostril alone and then the left nostril alone.

Dr. Ballentine has studied Ayurvedic medicine, homeopathy and yoga in India. “It’s like being unaware of the difference between walking on your right and your left foot,” he said. “You should know the difference. The right nostril tends to be more active, more outgoing and the left more passive and connected with one’s inner world.”

He had run us through practice in alternate breathing and told us to repeat it twice a day. First we placed our index fingers between the eyes so that the thumb could block the right nostril and the middle finger the left. We alternated in sequence making sure not to force the breath.

“This is a study rather than something to be followed mechanically. Do it, watch yourself and learn.”

During the lecture he recommended two washes of salt water–a nasal wash you pour in one nostril and it comes out the other, and an upper wash which he said was drinking salt water and throwing it up (shades of Herbal Ed in PSW-2). He asked his audience to list the main ways we excrete. Answer through lungs, skin and menses, mucus membranes and the bowels and the urine. He said Indians can’t understand why Westerners are so reluctant to talk about excreting.

He said it seems to the Indians that Westerners would rather keep their mucus inside than vomit it in a bowl. Dr. Ballentine’s statement recalls a phrase I read somewhere recently that we are a constipated nation. He said that grandmotherly advice to take a laxative at the onset of a cold was a good one because it would reduce the amount that had to be excreted through the nose.

He said that nicotine and tar from cigarettes are murder for cilia and will cause them to curl up and die, unable to continue their function. However, if a smoker stops they will grow back in six months, he said.

Nose operations can change personality. He told of a man who acted crazy before an operation and was fine afterwards, and conversely another who became psychotic after an operation and covered himself with shaving cream.

“To have one’s nose changed is tampering with a real part of yourself,” he told two women who were planning to have external nose operations.

Later Dr. Ballentine told me the institute has a graduate school of 43 students and that Glenview is the national headquarters with a dozen branches. He said about 2,000 patients, most of them local, come to the institute where they are treated by homeopathy, nutrition, breathing exercises and individual exercises including hatha yoga.

At that moment someone announced that Swami Rama was ready to see me. Dr. Ballentine withdrew. The Swami, wearing white robes and a red shawl, smiled broadly and ushered me into his plush inner office. He is about six foot one and not the diminutive yogi Westerners have come to expect from India.

I mentioned that I had come because of the experiments he had done at the Menninger Foundation. He pulled out a copy of Beyond Biofeedback by Elmer and Alyce Green and opened it to an experiment showing how he was able to control voluntarily the flow of the blood to the right hand causing an 11 degree temperature difference between one side and the other. He says in the book that is more difficult than stopping the heart. The Greens have engaged in pioneering studies of normally unconscious functions.

The Swami was generous. He gave me the book. Then he talked briefly. Self-training programs and self-awareness rather than self-care were his key phrases. He seeks mind control over body which if pursued by less disciplined mortals can help control epilepsy, high blood pressure and migraine headaches and more. Last June his institute sponsored a four-day conference in Chicago–The Second International Congress on Meditation Related Therapies. At the end of October in St. Louis there will be a similar symposium for the Midwest.

The Swami stressed: “One must understand one’s own capacity.” He talked of disease: “Everyone is treating sickness and no one is treating the man…We need to be strong from within, then we will enjoy wholistic health.” He said he is working on a manuscript on wholistic health. As I left he thrust a pomegranate into my hand and delivered me to Justin O’Brien in charge of his graduate programs and told him to make sure that I got some tea and a ride to the train.

Looking back I got a lot out of my brief meeting with the Swami. His graciousness recalls Elmer Green’s comparing him to a 17th century Italian nobleman. Green also recounts that the Swami showed some German doctors how he could cause a cyst to collect in his arm and allowed them to cut into it and then it went away. Swami Rama was disgusted when all that the Germans had to say was, “You are a very unusual man.” He felt they failed to realize the applications of the cyst which are that through self-training programs everyday adults can learn to control reactions to stress and be healthier.

Illinois Wholistic Centers in Churches

“The best medicine is not drugs but the patients themselves mobilizing their reserves. The wholistic approach involves the patient as a participant. The failure of organized medicine is in maintaining our health.”

This is the way Dr. Truman Anderson, executive dean of the University of Illinois college of medicine, opened the first session of a two-day symposium on wholistic health care in Oak Brook, Ill., Sept. 15-16.

In Illinois three wholistic centers operate in churches with family practitioners, pastoral counselors, nurses and volunteers. They are funded by the W. K. Kellogg Foundation and backed by the University of Illinois preventive medicine department.

In California the centers abound but they are holistic without the “w” and, besides the physician, include an array of dance therapists, acupuncturists, biofeedback machines, gestalt therapists and Rolfers.

Dr. Granger E. Westberg, a Lutheran minister and clinical professor of preventive medicine at the University of Illinois, the only clergyman on the staff, is president of the three wholistic health centers. “Losses are important,” he said in his lead-off speech. “Studies show that 38 per cent of patients show underlying losses six months to two years back. Ministers are natural grief experts to deal with that loss.”

He said the word psychosomatic has degenerated until it has become a putdown even though it means treating someone in mind, body and spirit which are the tenets of his wholistic centers.

“Stress is the in word today. Stress, loss, life changes and grief are the big four to look for,” said Dr. Westberg.

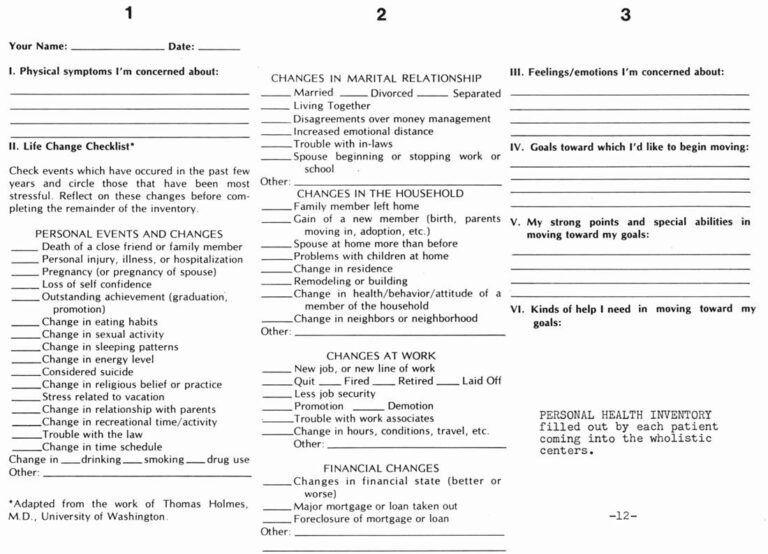

His centers have adapted a personal health inventory with a life change checklist from the work of Dr. Thomas Holmes at the University of Washington. Check points include “Death of a close friend or family member,” “Loss of self-confidence,” “Change in eating habits.” The chart places responsibility on the patient.

Dr. Westberg said there is a waiting list for volunteers at the Hinsdale Center opened in 1973, though in the beginning volunteers were afraid to talk with sick people. “We had to give them a course in ‘How to talk to people without doing too much harm,’” he said. “Volunteers do nutrition, money talks, cooking, how to raise children. We realized that health care is not just physiological, and doctors don’t have to feel guilty if they can’t do everything. They need physician extenders.”

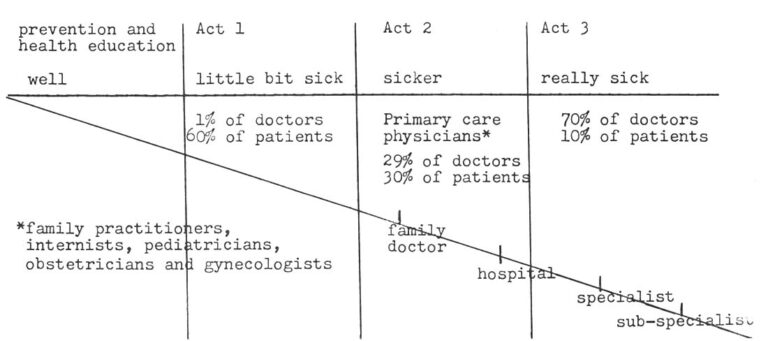

Dr. Westberg drew a diagram showing how patients enter the sick pattern where there are one per cent of the doctors till they reach being really sick where there are 70 per cent of the doctors. It is a chart in three acts.

He said the problem is that primary care starts too late in Act 2. “Sixty per cent of the sick in Act 1 are taking care of themselves with billions of drugs, most of them poorly used. Less than one per cent of the doctors are in Act 1.

“Act 2 has 29 per cent of the doctors and 30 per cent of the patients. Act 3 has 10 per cent of the sick people and all of the excitement of TV shows and 70 per cent of the doctors.

“I propose that 65 per cent of the doctors be in Act 2 and 30 per cent in Act 3. In Act 1 have nurses, clergy, lay people and social scientists like psychologists.”

Dr. Westberg said there are 375,000 physicians in the country and 300,000 clergy with 100,000 of them being untrained storefront ministers. That leaves 200,000 with training or about one-third good counselors. He said teachers should be trained in helping students deal with loss. “Any school has one in 20 of its’ students grieving either over the loss of a pet, parent divorcing or moving into a new area. We want to teach teachers to pick up the problem before they get to the doctor’s office.”

He said the clergy calls to the hospitals don’t accomplish much most of the time and often hospital chaplains don’t feel part of the healing team. He gave an example of a minister faced with a woman whose husband didn’t show up in church several weeks running because he was home sick.

The minister didn’t decide to intervene until the husband was finally admitted to the hospital. Then it was time to pray.

“Hospitals turn people on,” said Dr. Westberg. “Everybody gets excited when someone goes to the hospital. Nobody visits you at home.”

Dr. Westberg said that if the minister had gone to the house of the couple he would have found the husband despondent because he had lost status at work. He could have called the wife in on the conference early in Act 1 instead of waiting for Act 2–when the husband got worse and had to be hospitalized.

“We must sensitize the minister to early help and then make sure he gets the patient to a doctor for a physical so that he can rule out somatic symptoms,” he said.

Twenty-five cities have said they want to try the Hinsdale model of wholistic health center, said Dr. Westberg. They range from Cleveland and Denver to Palm Springs and Peoria. “All are to be located in churches which is an environment conducive to discussing the whole person’s problem,” he said. “The church is conducive to discussing family life because churches deal in the major crises of birth, marriage and death. We always deal in families and don’t deal in isolation.”

He said some doctors are not used to spending so much time with patients. “One walked out after five to six minutes with a patient, because he couldn’t think of what to do next. He was finished. He was untrained to deal with the human dimension of illness.”

The organization is moving into the Austin ghetto district in Chicago, but basically according to John Riedel, director of clinical development, it is middle class. Riedel, 30, on staff three weeks at the time of the interview, said hospitals are particularly willing to underwrite startup costs on a center.

“They are getting increasing pressure that they have to deal in healthier ways and not simply to get people into the hospital to keep business going. Hospitals can be a key. Churches give space and heat and janitor service and volunteers. Our biggest problem is getting physicians.”

The Kellogg Foundation along with the University of Illinois at the Medical Center sponsored the conference. Kellogg with $30 million funding 500 grants in 17 countries is the third largest foundation in the country. Sixty-five per cent of its grants are in health.

Participants included Rick J. Carlson, author of the End of Medicine, Dr. William R. Barclay, editor, Journal of the American Medical Association, Walter J. McNerney, president, Blue Cross Association, Dr. Malcolm C. Todd, past president, American Medical Association, and Dr. Dale Garell, medical director, Institute for the Study of Humanistic Medicine.

I encountered a light note during a reception the first evening. I was in conversation with John M. Lowe III, a fellow with the Kellogg Foundation. Since we were fellow fellows I asked him how the foundation feels about the sugar-coated cereals Kellogg makes. He explained quite seriously that there is a separation between the company and the foundation. He added that studies show that shredded wheat is worse than sugar-coated cereal because of decay caused by particles sticking between teeth. He also said that people put more sugar on cereal that is not sugar-coated than cereal that is. He didn’t know who made the study. Ah, well.

Received in New York on October 14, 1977

©1977 Phil Weld, Jr.

Phil Weld, Jr. is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from the Lawrence Eagle-Tribune. His fellowship subject is the role of self-care in health: a look at prevention, patient education and patient power in the U.S. and Canada. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Weld as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation and to the Lawrence Eagle-Tribune. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.