Imagine a phone pressed against your right ear. We’ll call it the outside phone because it blares messages, demands, oughts and shoulds from the outside.

“You ought to get up,” it says. “You should wash the floor. Take the 9:05 train. Go running. Hurry up with your writing. You’re way behind.”

Dare to hang up that right hand phone, blam, in mid-sentence, even if it is the phone you listen to all day and it turns you into an anxiety knot. Let quiet come. Don’t worry. Next time you pick it up it’ll be squawking as usual, a clever recording. You won’t miss a thing.

Now for the inside phone quietly cradled to your left. It connects you with you. Deep inside yourself run its wires. You pick up the receiver and listen, hearing nothing at first, then maybe the sound of cool, flowing water. Breathing. It is like putting your ear to the mouth of a conch shell. Finally a small voice comes from your center, just below the navel, the place the Japanese call the hara. There are many names for it.

“It is suffocating in here,” the voice says. “Give me more air.” Your breathing deepens in response to the cry that may have gone unheeded for days till you picked up the inside phone. The breather in you gets the message and the tension eases, tension from the push and drive of the outside phone. Then a stronger inside voice says: “I feel trapped. I want to stretch. Now I want a hug.” Or at another time: “I would like a quiet weekend” or “I’ve been wanting to change my job…”

The inside-outside telephone exercise is a way of helping a person get in touch with his or her innermost wants and to listen to that inside self. To my way of thinking it is self-care at its best because you can do it yourself, in your office even, simply by depressing the receiver button and listening. Try it. I think you’ll get some helpful results.

I learned about the idea from Fran Blum, 31, nutritional consultant also working on creative visualization and intuitive processes at the Wellness Resource Center in Mill Valley, Calif. The center is situated in an old redone house tucked back from the road in a redwood grove in the heart of Marin County. I had an interview with Dr. John Travis, the founder and physician of the organization now numbering ten staffers. Travis, a graduate of Tufts Medical School, calls his patients clients and doesn’t see them if they’re sick, but refers them to another doctor for diagnosis and treatment, inviting them to come back when they are well. Travis’s goal is to evaluate and enhance his clients’ level of wellness.

Each of the staff including Travis has a W.P. after his or her name standing for Wonderful Person, which is also the greeting used in letters from the center. It is also a certificate a client gets if he lives up to his client-staff agreement. The idea is that you must think well of yourself to be well.

Tom Ferguson, editor of Medical Self-Care Magazine, writes: “In it (the agreement) Travis agrees to provide ‘any and all information as to how you may achieve higher levels of wellness,’ ‘suggestions and recommendations for changes … which might enhance your well-being,’ ‘energy and support’ and ‘consideration of feedback from you.’ ‘The client acknowledges full responsibility for himself,’ realizing that his ‘health state is a manifestation of (his) habits, actions and behavior.’ He says he is ‘aware of the folly in blaming others for (his) experiences in life’ and aware that as a result of growth, (he) may decide to change friends, jobs, spouse or lifestyle,’ that he is ‘willing to enter into open, trusting communication and will use any feedback to benefit (his) growth’ and ‘will meet his financial obligations promptly.'”

If the client lives up to his part of the bargain, he gets a Grand Certificate declaring him “thoroughly, and completely beyond any shadow of a doubt a Wonderful Person, also known as Wonderbarus Personus. You can also get a blank certificate and fill it in yourself if you read or buy the wellness workbook. I was required to pick up a copy of the 100-page book packed with tests and information before I could be scheduled to interview Travis.

When I arrived for my hour appointment it was cut to a half hour because of last minute business, the rest of my time to be spent with Fran Blum and Barbara McNeill, coordinator of client services. The feeling was that visitors should see the wellness organization through the eyes of several staffers and the workbook and not simply through Travis alone. He has become well known in health circles because he is an M.D. who practices wellness and isn’t afraid to put plenty of responsibility on his clients. Other M.D.s report that wellness clients make excellent patients and are easy to treat when they are sick.

Travis kept me waiting a few minutes so that I had the luxury of examining his richly decorated office walls. There was a big cartoon of the pill fairy, a popular target of his, dropping a magic tablet to a non-wellness type, and a card saying “Don’t Worry, Be Happy,” with the face of Meher Baba, an Indian master. There was a big chart showing high-level wellness on the right and premature death on the left. On another wall was a poster of Sheldon Kopp’s eschatological laundry list from his book If You Meet the Buddha on the Road, Kill Him. I particularly liked the 43rd and final listing: “Learn to forgive yourself, again and again and again and again…” That seemed an essential part of self-care and wellness.

I enjoyed Travis’s eclectic spirit. His office was like his workbook, wide-ranging. It took from Transactional Analysis (I’m OK, You’re OK) and meditation and mixed with them a Health Hazard Appraisal to calculate how long you will live with your lifestyle and stress evaluation. He opens his workbook with the Bob Dylan quote: “Those who are not busy being born are busy dying.”

When he came into the room his long red hair covered a balding forehead at the top of his 6 foot 5 frame. He is 35. We started talking about the price of wellness at his center where a several month course can cost $1,500 or more. He didn’t think it was too expensive with hospital bed prices the way they were. He said he had spent $20,000 on his own wellness before opening the center. He spent it on travel and three years in therapy to handle his depression. “I had cycles of waking up at 4 a.m.,” he said.

I ask how he felt self-care tied in with wellness, and he replied: “The self-care movement is primarily looking at illness and how to prevent it, looking for signs, symptoms and disability. Self-care has more to do with treatment than wellness.”

I disagree with Travis’s assessment of self-care and don’t feel it is limited to illness but can naturally spread into areas of wellness if it helps the individual become more aware of himself, more able to listen to himself. The inside and outside telephones I feel are primary examples of both self-care and wellness.

But it is the fashion to down the other guy in order to show that you have something new. Travis said that in holistic and alternative medicine the patient looks up to the healer. Instead of drug capsules there are herbs, homeopathy and acupuncture needles performing on the patient. He went on:

“People who don’t express enough anger or get enough hugs are blocked. Four hugs a day is the MDA (minimum daily allowance), 12 is the recommended daily allowance.”

Travis left with a smile. He returned the next day at 9 a.m. wearing a black mask, ready to play. In his workbook acknowledgements he thanks the person who “assisted me in letting my little boy start to come out.”

In an interview in Medical Self-Care Magazine Travis said he is working as an educator, not providing medical services. He said: “I don’t think medical training is particularly compatible with wellness medicine. It’s nice to have that background, but I wouldn’t expect that anyone would use much of that in a wellness-centered practice.” He envisions a wellness practitioner working next to a family practitioner. He defines his role, not as taking care of a person but as “serving as a consultant to give them information, teach them skills, help them become more aware of their past, how to see what’s going on inside their bodies, how to visualize, how to communicate better, how to love and accept themselves.” He outlined eight specific skills taught at the center. They are:

“Relaxation, experiencing yourself directly rather than intellectually, removing self-imposed barriers, communicating feelings, creativity, visualizing positive outcomes, taking responsibility and loving yourself.”

I talked with Barbara NcNeill and Fran Blum after Travis left. McNeill said she had been emotional as a child and developed a severe sinus condition, the symptoms of which were quelled when she was 16. “They put on the cork but it came up somewhere else,” she said. She became a hippie and ate health foods. “Here people cheer when someone expresses an emotion at the moment. The group says thank you to the person. Now I appreciate my strong emotions,” she said.

“That is why self-responsibility is important, reclaiming your own space with an emphasis on regaining our humanity to break down the barrier between client and doctor,” she said. “A typical therapist position is to say, ‘I’ve got my shit together, and if you’re real good, I’ll tell you about it.’”

Blum, after demonstrating the inside and outside telephones, stressed that thoughts have a half-life “the power of a megaton bomb. Thoughts are really powerful…What a person thinks and feels is the way his body stays. Whatever you think about yourself happens… We are the sum total of our experiences and people we have known, and there comes a time to redefine and lighten the burden.”

She said she loved her parents who died of insomnia, blood clots and hypertension. They had served a diet that bored her. It was hard to refuse her mother who would say: “I’ll be upset if you don’t have another.” Now Blum has been strictly vegetarian for three years with occasional fish or fowl.

McNeill said proudly that the center is a greenhouse for “fledgling plants, a people greenhouse.” The place also helps her get in touch with the child inside her. “The child is the key to my heart and my heart is the key to my life. I have a child to raise inside myself,” she said.

I decided to come back the next morning for a $30 affirmation hour given by Ian Thomson, a staff member specializing on changing thought patterns to change the outcome of an event. “Our nervous system makes us as we are, and we think as we act. We can train ourselves to be any way we want,” he said.

The concept sounded unbelievable to me at first. In the workbook it says for someone desiring more money to say over and over again “I have all the money I need now.” Say this to yourself while surveying a pile of unpaid bills, even if it taxes your credulity,” Thomson advises. “Don’t say, ‘I don’t have enough money to pay my bills.’ That tends to perpetuate the undesired condition. Instead affirm the ultimate desired result.”

Thomson said to give attention to whatever it is I want, to have a mental picture of the desired outcome and not to worry about the way to get there. I told him I want to write a book. He reworded my desire in what he called the “positive present tense” as follows: “I write well and easily. My writing is a joyous pleasure to me. The ideas for my successful book flow, now in clarity and abundance.”

I am to repeat that for five minutes in the morning and the evening. When I say it, it is soothing. A mental image of my book floats before my eyes accompanied by a schedule of talk shows to publicize my writing.

“We create and recreate our own reality,” he said “When we struggle for goals we must look at things as finished outcomes.” He said affirmations have helped people stop smoking, control obesity or improve nutrition. “We fit the program to where the person is coming from.”

“Affirm what you want, not what you want to get rid of, such as affirming an undesired condition by saying, ‘My depressions are less severe.’”

“Notice how many negative affirmations people use. ‘I can never remember names,’ or ‘I’m fat.'”

There is a lot of Norman Vincent Peale and his power of positive thinking behind the wellness affirmation concept, but if you do it, it seems to help. I’ve been doing it. I used to spend days staring at my typewriter, nodding, reading magazines, drinking fruit juice, anything to avoid writing. Since I have been saying the affirmation production is up.

The workbook suggests making a map and choosing an area of your life in which you would like to bring about change. Get a smiling, good-mood picture of yourself and some spiritual symbol. State the outcome but pay no attention to how it will come about. “Remember,” it says, “abundance is the natural state of the universe. You are free to change your attitudes from scarcity consciousness to a state of abundant, positive expectation.”

The Wellness Inventory, a 100-item self-scoring questionnaire and one of Travis’s battery of 11 tests, focuses on issues of living that the regular annual physical in a doctor’s office doesn’t touch. It is one of the first things a client takes at the center. The inventory touches on things that make a difference — smoking, alcohol, fat, auto safety, apathy, stress and feelings. Here are some examples which you can check if they include you.

“I am frequently happy. It is easy for me to laugh. I have at least five close friends. For every 10 m.p.h. of speed, I maintain a car length’s distance from the car ahead of me. I usually meet several people a month who I would like to know better. I frequently touch and hold my children. I am able to say ‘no’ to people without feeling guilty. If I saw a broken bottle lying on the road or sidewalk I would remove it.”

My first reaction is how refreshing to have the statements be positive, instead of a checklist of negative diseases. The inventory helps you to determine areas of your life that might need attention. To obtain a copy of the inventory send 50 cents plus a stamped, self-addressed envelope, to Barbara McNeill, Wellness Inventory, Wellness Resource Center, 42 Miller Ave., Mill Valley, CA 01941.

The workbook abounds with other surveys to fill out.

The Eating Habits Survey checks among other things whether you eat raw fruits and vegetables or smoke before, during and after meals.

The Life Change Index, a popular measure of stress, marks 100 points for death of spouse, 47 for fired at work, 36 for change to different line of work and 12 points for Christmas if approaching. A score more than 300 is considered very stressful. Having a good outlet for this stress and having a supportive environment are essential to prevent illness.

There is a health questionnaire and regular medical history and a Purpose in Life Test. Example, complete in one sentence, “More than anything, I want…”

A test on assessing your body tension asks you to draw a diagram of the lines in your face. It provides a thermometer with the instructions that if you warm it with your thumb and can’t get it to 85 degrees, you are probably constricting blood flow to your hands. By relaxing and focusing on warming your hands, you can raise your hand temperature 20 degrees with practice. Warm dry hands indicate health, it says.

Optional questionnaires include a Health Hazard Appraisal. If your appraisal age is older than your chronological age, you are a greater risk than desirable. Some people’s age is 15 years older than their life expectancy giving them impetus to drop lifestyles leading to an early death.

“Physical illness,” Travis writes, “can result from misdirecting thinking energy by compulsive worrying (ulcers), self-depreciation, and hopelessness, lack of concentration (accidents), overachieving (high blood pressure and heart disease).”

The package includes a meditation booklet and a 54-book reading list. A Guide for Self-Exploration asks: “How do you think the universe began? Name your most important goals in life. What makes you happy and joyful? Describe the meaning of a frequent gesture you use. From what are you most likely to die? How old will you probably be? List 10 qualities about yourself which are precious to you.”

To measure stress, you may talk to a computer over the telephone in San Francisco. According to the tester, it will “uncover exactly those unconscious attitudes, behavioral patterns and conditioned responses which negatively influence your actions and are holding you back from greater self expansion.” You complete a series of statements such as “I am selfish” and then say Yes or No and the computer picks up telltale tension in your voice and computes it for $25 a session.

As Travis likes to say, “Wellness is an adventure not a medicine.”

A Visit With Michael Murphy and George Leonard

Mill Valley is an upper middle class suburb across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco. It is full of hot tubs, expanded consciousness and has such leaders in the human potential movement as George Leonard, author, and Michael Murphy, 47-year-old co-founder of Esalen Institute at Big Sur.

Though neither of these men are precisely students of self-care they are concerned with health. Murphy is particularly interested in athletes who are able to transform their perceptions or abilities for a moment, hear voices or attain a new clarity.

Murphy founded Esalen on his family’s estate at Big Sur on the coast south of Carmel in 1962. Scholars abounded on the grounds in the early years and it was not until the late ’60s that it got its reputation for public nudity in the baths, encounter groups and some eccentric therapies. Murphy has since quit as president and is one of four trustees of Esalen. He is no longer active in its management or administration.

His most recent book is Jacob Atabet, from a French Basque Family name. Murphy told an interviewer that Atabet “through his lifetime makes a descent into more intimate contact with physical reality, eventually down to the molecular, elemental and subatomic levels of his own body. He enters into the larger world at these levels. I have a theory that the body is an opening into the secrets of time, a sort of evolutionary star gate.”

I interviewed Murphy at his home perched on a hillside approached by long communal stairs. He was with his wife, Dulce, with whom he runs up to 50 miles a week. He said his focal work now is collecting anecdotes of high level transformations for the past six years with Jim Hickman, a parapsychologist.

They mean to document how we use our brains to accomplish physical transformations such as those done by yogis who stop their hearts or football players who become so aware at certain times they can anticipate their opponents’ moves. Murphy says the obvious conclusion is that if some possess these generally unrecognized powers it is more than likely that all of us do. And so he sees a new step in our evolution.

“I see Jim’s files as the first major study in the area,” Murphy said. “A lot has been done on the psychological but nothing on the bodily front. We are interested in anything that produces extraordinary functioning. One of the biggest sources is yogic literature.”

Murphy is especially fond of Joshua Slocum’s account (he was the first man to sail alone around the world) of a “helpful sailor” who talked to him for hours in Portuguese during his voyage. Murphy writes in an article, Sport as Yoga: “This disembodied figure claimed to have been the pilot of the Pinta during the voyage of Columbus and shared some of his knowledge with Slocum. There are many accounts of such helpful sailors. Being at sea may induce a state of mind like that produced through deliberate sensory deprivation. In such a state, normal perceptions may break down to open the way for other kinds of seeing — whether of projections from the person’s own mind or of beings with a life of their own.”

In a catalogue of altered states of consciousness he lists Golfer Bobby Jones under clairaudience saying that Jones often “heard a melody as he played and sometimes used it to give a rhythm to his swing. The sound of crickets or a subtle ringing sometimes comes to golfers in the stillness of their concentration.”

Murphy said a transformation can be “either a symptom of illness or the doorway to further development, first seen as a problem or as something wrong and later seen as a gift.”

He said that in his early teens during sermons in church “I used to be watching the priest in a center of a light. The priest was small” as if he were seeing him through the wrong end of binoculars. “I thought something was wrong till quite a few years later I talked to someone else who experienced the same thing.” Then Murphy began to regard his perception as a gift.

At Stanford where he was studying philosophy, Murphy meditated sometimes eight hours a day. He didn’t elaborate on the binocular effect or whether it continued during meditation. His first book, Golf in the Kingdom, is a self-described “journey into the soul, like an Irish fairytale.”

Murphy spent a year and a half in India — 1956-1957 — at the late Sri Aurobindo’s ashram in Pondicherry. At 31 he held his first job, working as a bellhop.

He expects to be working on the anecdotal part of his transformation project for the next five years and the whole project for the rest of his life.

“I think we have to gather much more evidence and then it’s decades or centuries for the practical work to be done,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “If you ask the right questions and get the answers, then you get more questions. Science doesn’t end something. It begins something.”

I found it hard to interview Murphy and also remain in the background. It was more a conversation than an interview, an exchange of experiences, so that when I left the man to pick up my Wellness Workbook and then visit George Leonard in his dojo or Aikido studio, I knew I didn’t have a complete story. In fact, I didn’t know what complete meant. Murphy was talking a lifetime project in cataloguing transformations and following them up.

Murphy was warm and relaxed with a pixieish twinkle in his eye. He told the Times: “If we had a larger social commitment, let’s say a program for the exploration of inner space on a par with the exploration of outer space, we would really see some prodigious things. The first step is realizing that we really do have some fantastic powers just waiting to be tapped.

George Leonard, like Murphy, shares a belief in human potential. I have admired him since the ’60s when I first read his book Education and Ecstasy which gave an ecstatic look at learning I never have forgotten.

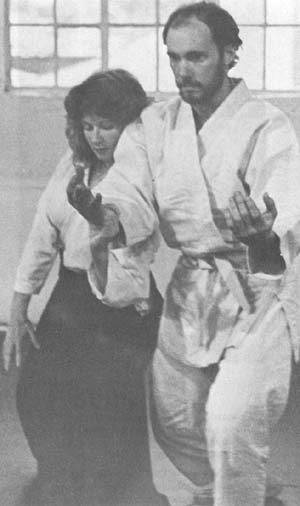

When I first saw him — 6 foot 5 and looking taller in white top and black swirling robe of the Aikido instructor — he was teaching an energy awareness class how to become invisible or at least inconspicuous.

First he had the group of 20 split up with half leaving the room. Then the other half tried to take up as much space as possible, to make themselves be noticeable. The offstage group walked through them and then it was their turn to do the opposite. Some persons ducked against pillars looking furtive while Leonard kept saying: “Don’t hide. Don’t hide. Become part of the background. Be either small or porous.”

The student who sat down beside the door like a street beggar in the Far East was the closest to being invisible. Leonard said he was casual. Those who hid crouched down, tensing, were the most obvious.

Leonard, white-haired and in his 50s began Aikido, a Japanese art of self-defense, in 1970. What I remember best about his class was his saying: “Stroke your opponent lovingly before the throw. You’ll throw better if you do it lovingly.” His hands caressed the cheek of his attacker as they spun around, joined, Leonard holding his head for throwing.

During a break a San Quentin guard and Aikido student, Charles Tackett, 32, who had suffered a blow on his left shoulder during a scuffle with prisoners, asked Leonard if he would extend his “ki” or energy into the soreness. Leonard, body swaying, stood over the kneeling man, and moved his hands within four or five inches of Tackett’s shoulder. After about five minutes of distance treatment he laid his hands on the sore shoulder.

Tackett later reported: “It is like an intense heat. There is no pain now. There was pain before. When he adds his ki power it is five times what I could send there alone. The best chiropractor can’t match ki. A sensei (teacher) has power that comes from infinity, like a woman picking up a car to free a child. She has ki…Aikido helps you become in harmony, in awareness of being, in harmony with self…George’s ki was like a booster generator to the blood I put into the sore area.”

M.D. Tells How His Ordeal as Intern Drove Him to Wholism

Today is my last day in the Bay area and I am to eat a brown bag lunch with Dr. Richard Shames, medical director of the Wholistic Health and Nutrition Institute of Mill Valley. He is on Rick Carlson’s list of people to see about self-care in health. Carlson, a Mill Valley attorney and author of End of Medicine, an Ivan Illich-style attack on the limits of medicine, has been kind enough to give me an overview of people.

I forgot to bring a lunch so I had to trot through the halls of the institute and Moment’s Pause, a sauna hot tub — massage place, and make my way to the takeout counter of a Howard Johnson’s. I emerged with a large HoJo’s coke tasting like mouth wash and a 3-D hamburger in a styled styrofoam holder. I wolfed both down while Shames was delayed outside. When he returned I had eaten my non-wholistic menu in time to watch him munch a sprout sandwich and a banana washed down with a bottle of Callistoga water.

I quickly learned he went to Harvard, class of 1967, seven years after me, but that engendered no backslapping or handshakes. We just exchanged the information. He went to medical school at the University of Pennsylvania and came from Florida.

He described his internship at the public health hospital in San Francisco as “full of inhumane treatment, a lot of mistakes and confusion and competitive backbiting.”

“One day I was beating on this guy’s chest to revive him and I find I am thinking, ‘If this guy would just die, I could get some sleep. I haven’t had any for 36 hours and if he lives it will be 60 hours without sleep.’”

Shames paused and turned in his chair. “I was appalled and shocked at myself. I am a fairly humane and idealistic person. There was someone having a heart attack. He had just come in. It was the last thing I needed…about midnight starting IV’s and putting tubes down people’s stomachs. I was following a system which is trial by fire for young doctors, an economic corps working for the hospital 80 to 90 hours a week at $8,000 to $9,000 a year. Inexpensive labor under the guise of training.”

He said he and his fellow interns were told they were spending too much time with patients, when the chart, which was a legal document, needed more time. “The charts got much more time than the patients. We were treating the charts,” he said. “We were supposed to see a patient only one minute. I’d want to spend 5 to 10 minutes or sometimes an hour. They (his supervising physicians) had faith in technology. What the patient said wasn’t important against the lab tests.”

Shames said that in his training hospital there was no single anchor person to watch over the patient, that lab and x-ray were income generating and charges for room and food service were losing money. “Regardless of risk or discomfort, the doctors ordered tests, now even more so because of malpractice defense. A person was a body breaking down, a piece of flesh,” he said.

Seldom considered was why people got sick or how they should handle themselves when they left the hospital, Shames said. The doctors ignored nutrition, physical fitness and psychological factors and had only one social worker in the hospital.

“For the doctors, getting people well meant lab tests and quoting different journal articles,” he said. “They-spent more time talking to each other than talking to the patients. Nurses they regarded as bumbling pill pushers, bed makers, while it seemed that nurses did the majority of healing in the place and saved the patients from ridiculous orders.”

Shames said once he had to tell a man with fast growing lung cancer that he was going to die. “I spent 40 minutes with him. The attending physician and resident told me that was too long, that I shouldn’t get too involved,” he said. “Someone with a fatal illness was ostracized. They lost interest in that person who was going to be a failure (by dying).”

Once a new patient, diagnosed as having lung cancer, announced he wanted to leave the hospital and go to his cabin in the mountains. “He didn’t want the needles, radiation, cobalt, chemotherapy and transfusions. It seemed sensible to me that a healthy guy would choose to avoid these, yet the doctors said he was not in his right mind…Another guy, about 85, was being kept alive against his will. He finally died. Later at grand rounds I said we were doing wrong by keeping him alive against his will. I was told this was a teaching hospital and they wanted us to learn to take care of a variety of people. I replied the best way was to do the right thing by every patient. The chief of residency didn’t like me much after that.”

Shames eventually finished his medical training and went to work for the Marin County Health Department.

During that time he answered a call on a woman at the University of California medical center. She had been bloated with water and was vomiting. Authorities suspected a malfunctioning kidney, operated and took out a harmless little piece of fat they had suspected from x-rays was a tumor.

“I talked to her and learned that she had drunk great quantities of water. It was a full moon and she said she was a part of a cleansing cult involving drinking great amounts of water. The kidney specialists hadn’t even talked to her. It took me 10 minutes to find out what could have saved her surgery,” he said.

Shames said that the moment best for teaching a patient was at the time of illness when a person is ready to listen to preventive medicine. He is an internist who coordinates his department of medical services at the wholistic institute with an eye to preventive counseling as well as expanded general practice with a focus on casual factors. The approach employs medical therapy, physical therapies, hypnosis, and nutrition.

The institute has 25 persons on the staff, plus another 25 giving classes. Other departments include health resource guidance to advise people on what is sensible for maximizing well-being; nutritional services; psychological services; orthomolecular psychiatry treating emotional problems with concentrations of nutritional substances. Also, homeopathy, podiatry, spiritual consultation by a clairvoyant, and acupuncture.

Shames explained why he didn’t choose a traditional medical practice as a suburban internist, but he didn’t state how the therapy practiced by another competent young internist would differ from what he practices at the institute. I report his remarks about his internship because they seem to represent a prevalent criticism of attitudes in hospitals. As far as self-care and preventive education he found little in his teaching hospital. I understand though, that some hospitals have been shifting emphasis since Shames was an intern and are focusing more on patient education and preparing patients for life after discharge from the hospital.

For my final newsletter I am exploring government and industry and how they are teaching self-care and health promotion. I want to know if there is any real commitment to prevention of disease when the big money is being made in curing, testing and hospitalizing after the person has already fallen over the cliff. I want to see if there is any commitment at the governmental or industrial level to encourage people to change their lifestyles — diet, exercise, tooth and gum care, using seatbelts and not tailgating, stopping smoking and driving while intoxicated. I suspect it will be at the community level the information leading to a lifestyle change will have to be taught. I have spent a year examining the whats of self-care and prevention. Now it is time to see how it can be implemented and against what resistance.

©1977 Phil Weld, Jr.

Phil Weld, Jr. is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from the Lawrence Eagle-Tribune. His fellowship subject is the role of self-care in health: a look at prevention, patient education and patient power in the U.S. and Canada. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Weld as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation and to the Lawrence Eagle-Tribune. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.