COLUMBUS, Miss. — The shanty shacks began in Eastern Arkansas and paralleled the Mississippi River delta well into Mississippi. I couldn’t help but notice them sitting small and alone washed by still seas of brown earth that lapped gently at the edges of doorsteps.

I also noticed the children playing in the yards of dust. They seemed, for the most part, content in their games.

It was a gray day. Planes swooped from the haze like giant phantom eagles across the concrete ribbon ahead, carefully depositing their airborne cargo on freshly-plowed ground. The drive across middle Mississippi was table-top flat. One young fellow with lengthy hair broke the monotony by passing in a roar. A sticker proclaiming, “Smile, This is Wallace Country” was stuck to the rear bumper.

About 28,000 people, one-third of whom are black, reside in Columbus. It’s where the original Memorial Day began shortly after the Civil War and, since it largely escaped the ravages of that conflict, many antebellum homes stand as reminders of that era. There is also the nation’s first public college exclusively for women.

I was intrigued, as was Kathy, by the color mural on one wall of the city’s downtown post office. It is a painting, I later discovered, commissioned for out-of-work artists during the WPA years of Roosevelt’s administration, depicting cream-colored Negroes laboring in a cotton field.

A man named John Henry, the portly and mustachioed president of the Merchants and Farmers Bank in Columbus, told me he feels there have been drastic changes in racial understanding during the past decade in that state.

“It’s happened fast, faster than anyone thought it would,” he said. “Perhaps it’s because the blacks and whites have lived side by side in Mississippi for hundreds of years, unlike the cleavages which are now manifesting themselves in places like Boston.”

My liking for Henry was rooted partly in the fact that he is a former journalist who served as a war correspondent during WW II, and had been a personal acquaintance of the late Ernie Pyle.

“I was with Pyle on the day before he died. He was feeling bad…but then he was constantly complaining about his health. He said he was going to bed for a few days, but that didn’t last. He went ashore the next day to cover the mop-up operation on a small island and was killed.”

Henry adjusted a green tie and dropped back against his chair. “Pyle told me before we left for overseas that last time that he didn’t think he would be coming back home. He had a premonition about his death.”

John Henry was with the now defunct International News Service in New York when he eased into the correspondent slot. He returned to his home town to assume the leadership of the bank formerly headed by his father.

I sensed from our conversation that he cherished those years as a newspaperman…I also secretly imagined how independently wealthy he inevitably would have become by now had he only stayed a newsman…

Manuel Taylor was on his hands and knees yanking weeds when I walked up on him. Now 64 and heavy, the Negro grandson of a slave is also a heart patient. He told me he’s fathered four children, the youngest of whom is holding down two jobs to save enough for college tuition next Fall. He wants to be an architect.

Manuel stopped for a moment to dab at rivers of perspiration rolling from his rotund face. Brandon, the five-year-old member of our traveling trio, sat beside him and began digging in the dirt.

“I have four yards that I keep now,” he continued. “I sure don’t want anything for nothing, no sir. I’ve done hard work all my life.”

He spoke openly with me about his life and memories. “I most recall getting up at three in the morning when I was small to go to the fields with my father. His father died 34 years ago. “I’d make 40 cents for working all day, but shucks, back then a day’s wages would buy you enough food to where you couldn’t carry it all home. Today, you work all week and take it home in a few small sacks.”

Manuel agreed with John Henry that the storm of racial conflict has passed in Mississippi during the past decade. “There’s only a few who make it strained for you nowadays.”

He said he suffered a heart attack last October while he lay on a bed after a full day’s work. But the doctor allowed him to work in four yards a week after the recovery.

Manuel lives in a small house not far from where he labored with his father in the fields. One day, he said he’ll lay down his five-foot, nine-inch, 224-pound frame in the raisin-colored soil where his ancestors toiled away lifetimes.

The most exciting thing he can imagine is a son who will earn a college degree…and the possibility of getting his free state fishing license a bit early, “before I officially turn 65 next Fall.”

Brandon had managed to shape several handfuls of dirt into a miniature raceway for his pocket-sized cars and, as we were leaving, Kathy half-heartedly scolded him for “messing up the man’s yard.” Whereupon Brandon promptly informed his mother, “This isn’t the man’s yard, mom, it’s God’s yard…”

We spent four days in Columbus, then drove through to Memphis. The conveniences of our as-yet-unfamiliar motor home made the trip pass quickly…but then, not having to stop for the “I’ve got to go’s” shortens any trip considerably.

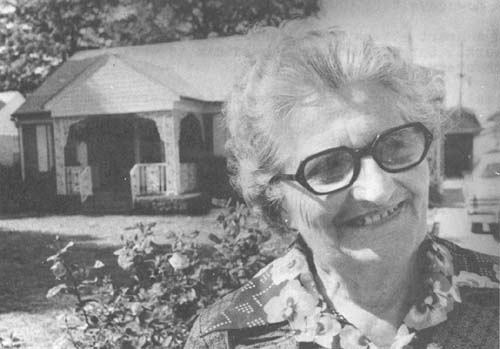

MEMPHIS, Tenn. — Dorothy Boswell is one of those people who will argue a glass is always half full, rather than half empty.

Twice widowed, the remarkable woman grew up raising herself and six others until they finished high school. Those who know her contend she’s been doing nothing but giving ever since.

For instance, there’s an 83-year-old woman named Bertha Spears from Memphis, who has been the recipient of a 20 or 30 minute personal call from Dorothy each weekday morning for seven years, yet they have never met.

Dorothy calls Bertha, also a widow whose eyesight has failed in recent years, to read a morning devotional and “Just chit chat” because she wants to help.

She said, although the two women live only four miles apart, they have tried to meet three different times but, “for one reason or another, have always missed each other.”

I was interested to know what could motivate a person to be concerned enough about someone she had never met to call her more than a thousand times.

“Why, isn’t that what life’s all about?” she said,”…caring about one another. When you take that out, what else have you?”

The 64-year-old native of Mississippi lost her husbands, Hoyt and Fred, and her father to heart attacks.

Her lawn on Tisdale Street is filled with a bevy of delicate brightly-hued flowers and her back yard is a large vegetable garden. Living room walls are hung with paintings and drawings, all gifts from family members. It’s a comfortable home that reflects her personality.

She even asked the three of us to spend the night with her and explained what a fine breakfast she’d prepare in the morning…and I know she meant it.

Aletha and Mike have lived in Memphis all their lives. He’s 17, but she’s not quite. They’ve been married seven months and firmly believe there’s nothing they can’t overcome. They live in a rented mobile home and hope to buy it someday, “when we can save a couple hundred dollars.” He’s a repairman for a vending machine company and vows he’ll finish high school through the GED program.

I had to ask why, in the face of universal hard times, were they so certain about the future. “Well, I figure we’ve got to really buckle down right now just to get by and the rest will take care of itself.”

“Frankly, I think the problems exist mostly in people’s minds. The majority begins thinking negative and it makes things appear worse than they really are. The first thing we’ve all got to do is quit thinking so negatively.”

Mike is 6’2″ slender and handsome. Aletha is short with long flowing blonde hair and a pixie face. Together, they appeared able to conquer any obstacle. Aletha’s father said Mike’s approach to asking for his daughter’s hand went something like this, “Well, sir, if some 17-year-old kid asked to marry my daughter, I’d say heck no. But this is different…”

Mike’s grandest dream, he confided, is to one day become a master welder making $12 or $13 an hour. It was inspiring to see such a very young couple eagerly strapping on their track shoes for the only marathon race I know of where hurdles grow larger as the game progresses.

While we rearranged the 25-foot “Lady K” for departure, I asked Brandon what, thus far in the trip, had meant the most to him.

He grinned his sly grin and mentioned the toy race cars he had received as a going away present and the squirrel he saw the day before. Kathy said it was a dumb question.

I had read about Buford Pusser and watched the movie of his six-year exploits as Sheriff of McNairy County, Tennessee, two hours east of Memphis. When the wheels on the Lady K again rolled, they were in that direction.

SELMER, Tenn.— It was a 30-minute drive into Selmer from where we had parked the Lady K, among the towering pines of Chickasaw State Park.

The town, made legend by the exploits of the late Buford Pusser was much like most small southern communities…a main street, court square, quiet atmosphere and a foreboding metal-colored courthouse that vaguely resembles a windowless battleship.

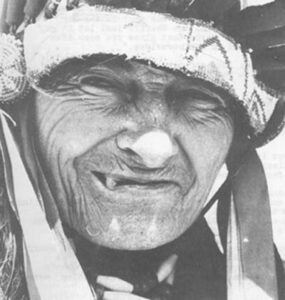

I soon encountered an olive-skinned fellow named Jim Moffett, who said he was the first deputy hired by Pusser in 1964 and his Chief Deputy during Buford’s six years as Sheriff.

Moffett was somewhat reluctant to speak to me at first. But as we sat, he began to talk about himself, a story which was not as flamboyant as Pusser’s, but interesting in its own right.

Jim was born in McNairy County on January 22, 1923. He grew up among the rolling hills of that area where he met and married Juanita.

A farmer by trade, he weathered the results of a poor crop 20 years ago by accepting the job as night watchman in the small town of Adamsville, about 13 miles from Selmer.

Adamsville, also Pusser’s home town, was without a policeman, a jail, or even a city hall back then. But they did have a Mayor, who later asked Jim if he would become the town’s policeman.

“Those were lean years,” Jim said. “Why, we didn’t even have a car or a jail. If I made an arrest, I had to send the prisoner to Selmer in a taxicab.”

He said he prodded the Mayor until some type of city hall was established in Adamsville. It’s now a small white building on Main Street.

Now a Chief Inspector for Sheriff J. 0. Gray, Jim claims he has made more arrests than any other man in McNairy County. More interesting to me was the fact that in 20 years as a lawman in what movie billboards proclaimed “Murder County USA,” Jim has never been shot, or shot at, or knifed or even a gotten a “simple beating”. Sheriff Gray said he has yet to fire his first shot at a person or be fired at.

He still maintains his 34-acre small farm near Selmer, a farm where he and Juanita have reared 11 children. Four are foster, including one whose mother hanged herself when the child was four.

We left the courthouse and climbed into Jim’s car for a ride to Adamsville. He continued his story. “When Buford came into office in 1964, this was a dry county. Things were a lot tougher, but not anything like the movie showed. I walked out of that movie. It was totally ridiculous.”

I later talked with Pusser’s mother in Adamsville and she agreed with Jim that the movie about her son was misleading.

“Anyway,” Jim continued, “four months after Buford took office, the county was voted wet and moonshine was on the decline. I will say that for nine months it was just me and Buford. We raided one heck of a lot of stills together…87 in one month, without a shot being fired. Nowadays, our major problem is with drugs…just like everywhere.”

We passed the spot marked by a historical sign where Pusser’s car crashed and burned about two years ago. Jim firmly believes the death was an accident. “I pulled Buford out of two wrecks myself while he was Sheriff. He drove fast, very fast all the time. He was bad to go to sleep at the wheel.”

In disputing the movie, Jim said Buford never carried or even had a big stick of any size or shape, that he did not climb out of a hospital bed to attend his wife’s funeral, that he never hired a black paid deputy and that he always drove himself back from shooting fracases he was involved in, including the ambush that claimed his wife Pauline’s life in 1968.

Also, Jim said Pusser never stood in any courtroom and bared his chest to a group of jurors to display knife wounds or ever had a feud going with a local judge during his years in office.

He cleared his throat and returned to his story “When Buford was Sheriff and I was deputy, he paid me $150 a month plus $5 for every arrest I made,” Jim said. “I’d come in at 7 a.m. and Buford would come in at three in the afternoon and work until late at night. I’d say we have half as much to do now as we did then, but our statistics on burglary and dope have tripled.”

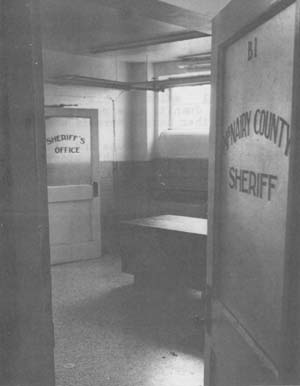

The small basement office where Pusser, Jim, and the other four deputies once worked together now stands empty. Two worn chairs sit at odd angles behind a shabby desk and exposed pipes traverse the ceiling. The Sheriff’s office was moved to larger accommodations down the hall several years ago.

Jim is up at 5 a.m. each day, tending to 37 head of cattle. “I also have one hen, three guineas and a duck,” he said with a chuckle. “Before this law work came along, I had 480 acres and three tractors.” He’s usually at the courthouse by 8 a.m.

The Great Depression took its toll on him, as it did most Americans in the 30’s. He dropped out of school when he was 12 to help his father work the farm so they’d have food for the table.

Back at his office, he pointed out a small whiskey still taken the week before, “Moonshining here’s not entirely dead, but this isn’t common anymore.”

I asked how Sheriff Gray lives down the “Walking Tall” story and Jim said he doesn’t try. “I’ll tell you this, J.0. Gray is probably the best Sheriff I’ve ever served under.”

Heading back to the campground, we stopped for bread and milk — and one “after-dinner chocolate surprise” — Kathy wanted to know everything I’d discovered, but I wasn’t certain what I’d digested, except that deputy Jim Moffett, in his own right, is an unusual lawman.

CHICKSAW, Tenn. — I had just put charcoal on the grill when a boyish-faced park ranger appeared from behind a tree. Andy Williams…claimed he never sings…has been a ranger for three years.

He lives in a house on the outskirts of the park, about ten miles from where we were camped. A soft-spoken, friendly and somewhat shy man, Andy had majored in agriculture during his college years.

I also learned he literally backed into a lifelong career by accident. “I was desperately looking for a job,” he said, “when my wife called an old school friend of hers just to talk.” As it turned out, her friend’s husband was the assistant director for state parks and Andy ended up on the line that evening.

“He told me to take the Civil Service Exam and that he’d do what he could for me. I took the test and six months later, I was accepted. It was the day after Labor Day.”

He took about 250 hours of training for his job. The day before we arrived, the 32-year-old ranger said he had worked from 8 a.m. until 10 P.M.

His wife and two children enjoy living away from civilization as much as he does. The kids attend a small country school nearby. Backing out of camp he asked if I’d like to ride through the campground and collect fees with him for a while. I could tell from the look in Kathy’s eye I had spent enough time roaming that day. For the sake of harmony…and my growling stomach…I declined and stayed to fix the hamburgers. He smiled and said his wife was jealous of his time, too.

Decaturville, Tenn. — The next morning we wheeled the Lady K onto Highway 100 and headed for Nashville. I flipped on the CB and heard “The Crayfish” calling.

Little did I know that after 30 minutes of radio contact we’d be invited to sit in the Crayfish’s living room over coffee and discuss his life as the pilot of a river towboat.

Paul Parrish…his wife, Frieda, spells it “Parish”…is one of those fellows who gingerly herd massive barges down the river. He works along the Little Green River in Calhoun, Kentucky, and spends three weeks on the river and three at home. He said he usually works ten hours a day and sleeps with five other crewmen on board the “Nancy B”.

Frieda said she occasionally makes the three-hour drive to Kentucky to spend time with Paul during the work weeks.

They live in a modest but attractive red brick house overlooking the highway where we had left our six-wheeled house. There are three little Parrishes, but Brandon missed them since they were in school.

Paul has navigated the river for ten years without an accident. He started as a deck hand coupling barges together and spent extra hours watching the pilot and learning the job. It sometimes gets pretty exciting shepherding several fully-loaded barges between the banks of a swift river, he said. “I usually push four barges, but last week I had nine on the front end of our 1,000 horsepower boat. That’s like pushing a river boat with a small outboard.”

Paul left the river a few years back to try his hand at local factory work, but he didn’t like the jobs and returned to the boat within two years.

They laughed when recalling their years of marriage. “Actually, we’ve been married twice,” she said. “The first time in 1961 for seven years, then we split up until 1972 when we remarried.” Paul said they “decided to remarry after we grew up.”

Before we left, Frieda handed Kathy a quart of freshly-picked strawberries and Paul offered a thought about America. “We better get some people up there in Washington who are honest. Followers are only as good as their leaders. It’s disgusting to see some of these leaders making thousands and thousands of dollars and not paying any taxes on it.

“I made $18,000 last year and paid $3,000 to the government.”

We could have spent several days with the Parrishes…”Parishes,” but we had eyes cocked on the musical city of Nashville and Brandon couldn’t stop talking about Opryland.

Back in Lady K, I thanked ole Crayfish over the CB. We would always remember their hospitality and I finally understood where he got that handle.

NASHVILLE, Tenn. — The song says there are “1352 guitar pickers in Nashville”. I managed to find one of them.

Chuck Spence is a 21-year-old bass player with a band called “Friends and Neighbors”. He’s been playing music since he was nine and decided to be “a picker” after finishing high school.

Chuck said he once played with a group called the “Hard Times”, but it folded. He’s strummed his guitar in many clubs and told me he was roaming the country for nine months last year.

It was dark and crowded in the club where we talked, so I had to shout frequently which caused the fellow at the next table to think we were fighting.

The young man performed well enough to earn an audition and resulting performance at nearby Opryland, new home of the Grand Ole Opry, recently but he also claims talent’s not enough when it comes to stumbling across the rainbow’s end in Nashville. Most musicians who get jobs are members of the union. Chuck said he carries a membership card.

It was interesting to realize how many musical livelihoods there are in the city. “Not everyone’s a picker,” he said.

A musician can do “sessions” or “gigs”, or cut records, or write music and lyrics. There are not only country musicians in Nashville, either. Chuck said rock, country rock, and gospel musicians abound in the musical city.

He brushed shoulder length hair to one side and his expression grew serious, “If I could have my dream, man, it would be to own my very own music store. Did you know there’s 100 to 150 percent mark up in most stores on musical instruments?” I had to confess my ignorance, but I wasn’t surprised.

Why, I wondered aloud, does he want to remain caught in the vortex of such a chancy, competitive profession. “Well, I’m playing aren’t I?” he said. “I play because I love it and I can make good money on the road.

“On the road, a good musician can clear $500 a week. If we continue rolling like we are, I imagine we’ll soon be clearing $200 a week here. What I’m making exactly is confidential.”

He said his father is a real estate broker and he has a sister 30 and a brother who is six. He said his parents don’t object to his musical aspirations and added he plans on acquainting his little brother with the guitar next year.

There was a time in the near past, Chuck said, when the pickers of Nashville would gather after the Opry in a building downtown and “just pick for the fun of it. They don’t do that anymore though.”

He also mentioned the existence of a “musical clique” in Nashville and claimed those who want a leg up on the stairstep to recognition have to be on the inside.

We spent an hour discussing his career and other musicians he knows. He was due to perform as our conversation wound down, but he took another moment to say he believes the successful clubs in Nashville are managed by “the club operators who are in tune with what the people want…not what they think they should have.”

Not knowing otherwise, I accepted that, especially since the Pirates Den Club was packed to the walls that night.

I also spoke with a bartender named Ken Harris later that night and he told me his brother is playing with “The Winter Brothers Band”. Ken said they’re trying to break into the record field…but he just doesn’t know…I told him to give his brother my best wishes. I was beginning to see how many capable bands and musicians there are trying to strike an influential eardrum in that turntable city.

My definition was…nasal lessons of life and love set to music that compliments the twang of a guitar string. But whatever description, the music of the Grand Ole Opry was puredee American and pretty doggone contagious.

Entertainer after entertainer stepped to the glistening microphone to belt forth his or her version of life’s “done me wrongs” with which everyone could identify.

There was an indefinable spirit circulating among the 4,000 or so people in the gigantic, carpeted auditorium. People sat spellbound as countless “yee haws”, screams, whistles and shouts rose to accompany the picker on the platform who was totally absorbed in delivering his rendition of, “I Saw the Light.”

Individual groups in corners were clapping out their own rhythms. Others were strolling to the front to shove personal dedication messages toward the entertainer. He graciously bent to accept, although halfway into his song.

Without realizing it, I glanced down to see my own leg thumping out the time. Brandon was more interested in studying the hundreds of lights high on the ceiling above.

Most of the audience was middle-aged or older. There were many balding heads in the crowd, but there were also high school students who bellowed when recognized on the stage.

Another glance at Brandon found his leg held high above his head in the seat and he was yanking on a slightly-soiled sock which dangled beneath the nose of a Stonewall Jackson fan. He wrinkled his nose and whispered that his toe itched.

We left the Opry with what I confess was a renewed respect for country and western music. Brandon said simply that he wanted to go ride the Flume Zoom.

Opryland is probably a lot like what America will become a hundred years from now…a clean, concrete good-time with a semi-carnival atmosphere.

I noticed a young girl collecting bits of trash paper from the concrete and we struck up a brief conversation. Her name was Debbie Westerfield and she was 18, but would be 19 the next week.

I asked how she liked collecting bits of discarded trash and she said she asked for the job because she got to move around the park rather than sitting in one spot all day.

A mist began falling and she covered up beneath a parka raincoat. The teenagers who worked at Opryland can have their pick of jobs most of the time, she continued. They can sell ice cream, balloons, work the ticket gate or clean up the grounds. Her instructions are to pick up everything on the concrete that’s not supposed to be there.

She told me she’s originally from Oklahoma, but moved to Nashville when her mother, who was divorced, remarried a man from Nashville.

Debbie also said she enjoys her job and the frequent parties thrown by the teens at Opryland during the summer.

The mist turned to a downpour and we parted with hasty good-byes. She scampered off toward one building and I to where Kathy and Brandon waited. That day, I ended up riding the Flume Zoom twice with Brandon. Kathy would only go once and she sat in the back with her eyes closed on that trip.

Later, she confessed her favorite ride at Opryland was the Belgium Waffle where, for only 65 cents, a young man seats the patron in a chair and dares him or her to consume an enormous plate of starch and whipped cream topped with egg-sized strawberries. She rode twice.

We spent three days in Nashville, and before we departed, I telephoned a man named DeFord Bailey who, I’d been told, was the first black man to appear on the WSM Grand Ole Opry radio show. He supposedly played a few tunes on the harmonica as a young man and was still around Nashville, although now elderly.

It seemed rather indicative of an attitude in America to include Mr. Bailey’s response to my inquiring about his life. “You’ll have to talk to my business manager. I’d have to have some money to talk to you about myself…” I shan’t reveal my response to Mr. Bailey.

For a month before this odyssey began, people had been telling me not to miss the Smokey Mountain region of America. Our sights had been realigned and, once again, the Lady K was rolling.

PIGEON FORGE, Tenn. — Not long after we spied the towering foothills of the Smokey Mountains, we encountered a Bicentennial wagon train bound for Valley Forge.

The 36 covered wagons were parked, ironically enough, behind and beside a fast-food burger palace.

Traffic was backed up. Tennessee State Policemen were blowing whistles, using loudspeakers and strutting importantly. I decided to park and mingle among the concrete safari for a while.

Dickey Jacobsen cut a conspicuous figure, sprawled across the front of a trooper’s car in grimy blue jeans, unkempt hair and a set of chapped lips that would have made Ward Bond envious.

The 20-year-old native of Tick Faw, La., left his girl friend, Gwen, on Feb. 12th, and joined up with the train in Baton Rouge, La. It just so happened he was riding in and driving the Tick Faw wagon which was originated by Gwen’s father and brother, “Big and Little” Jim Jenkins.

Big and Little Jim and Dickey had been slowly clopping eastward for about three months. He told me he either writes or telephones Gwen once a week and swears he’s not going home until their wagon circles up at Valley Forge.

“At first,” he said, “I was just going for the weekend. But I ended up staying all the way.”

Dickey said life on the wagon train isn’t that bad. The evening campfires and songs add a lot, along with the camaraderie and sharing between the travelers.

Most evenings are spent camped at schoolyards, football fields or fair grounds. Dickey said he’s eaten “lots of canned food in the past 12 weeks and 1,400 miles especially Vienna Sausages.”

I couldn’t help but wonder why a young man would want to spend so much time in pursuit of what philosophically boils down to a patriotic gesture in observance of America’s birthday. “It beats working,” he said with a laugh, and then he changed expression to explain how he had grown up on a farm and how much he enjoyed the out-of-doors and “roughing it.”

He shoved his weather-beaten western hat back on his forehead and took a long draw from a waxed cup filled with soft drink. A mustache grew from his upper lip and raced down the edges of his mouth to unite with a fledgling beard.

Highways, he went on to explain, are particularly hard on the horses, hooves and the animals have to be reshod about every two weeks. I also learned there are many more men on the train than women and that the blue wagons are the official Bicentennial variety while the others, like Big and Little Jim’s, are independent wagons from different places that just wanted to go along.

Dickey and the Jenkins merged with this train in Milan, Tenn. The original train they joined began in Houston, Texas and there were also portions of trains from Alabama and Florida now banded together in this traveling road show.

Dickey said the Tick Faw wagon was the only independent wagon on the Louisiana train when they reached the Mississippi border. He also talked of the church bells that have tolled in many towns for them as they plodded through the streets.

The young wagon driver said he’s one of eight children and his mother, Betty, and father, Henry, still operate a Louisiana dairy farm with about 150 cows.

There was a sudden shout and members of the train began scurrying everywhere, clutching fried pies, soft drinks and greasy burgers. Some men dropped to their knees and examined their horses’ hooves, others were hurriedly greasing wagon axles.

Those who had assumed a face-up prone position in the nearby roadside grass, stirred to their feet. The younger spectators were emitting “oooooohs and ahhhhhs” and obviously enjoying the excitement.

The wagon master shouted a television version of “Waaaaagons Ho” and the prairie-schooner procession began to file slowly past. I admit to a slight shiver of excitement laced with a twinge of pride, admiring them for having the courage and motivation to undertake such a journey.

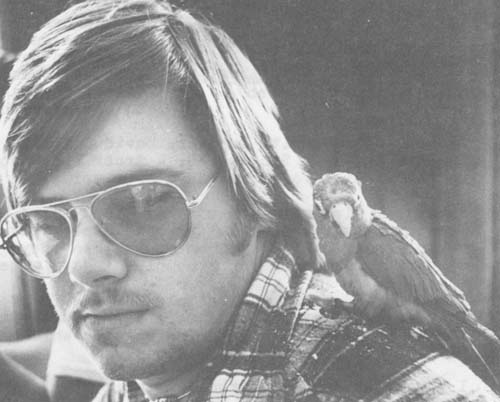

Gatlinburg, Tenn. — We were about three bites into a terrific salad at Ugle’s buffeteria when Brandon began unexplainably laughing aloud. At first I thought there must be a sliver of radish embedded somewhere in my mustache, but I discovered it was only a young man with a parrot on his shoulder.

Three fellows and the bird had seated themselves at a table beside us and were busy discussing their meal. I decided I’d mind my own business, but it was too much when he sat the small green and yellow bird on the edge of a water glass and handed her a chip of his cracker for lunch.

Introducing myself, I asked about the bird. Don Sharp, a 21-year-old bartender from Memphis, said he bought “Smokey” six months earlier for $85 in a pet store.

Jabbing a forefinger toward her, she fluttered aboard for a quick ride to his shoulder. There she continued her feast on the cracker in between suspicious glances in my direction.

Don said he took her everywhere with him except to work. Her wings had been clipped, but he said she never wanted to leave his shoulder when they are out.

He has become accustomed to the frequent stares of those surprised by such a common sight as a parrot on board a husky young man. The most frequent question fired at him is…can she talk?” She can’t, but I can attest to an ability to squawk with the best of them.

The two fellows with Don were David Chastain, a 25-year-old fireman from Memphis and Glen Stovall,22, a truck line dock worker. They said they had come to the Smokies for three days of camping.

Smokey, I discovered, has a boyfriend named Sam who is somewhat larger and far more aggressive according to Don, especially when it comes to sharing her. “You almost can’t get them apart when they get together each week. Smokey stays in a bad mood for a couple of days afterwards.”

David interjected. “I’ve told Don the first egg they have is mine. I’m going to give it to my wife and tell her to baby it.” Don smiled and offered the parrot a sliver of fried chicken which she refused. ” Figures,” he said. “She doesn’t care for fowl.”

I was reluctant to intrude on their meal any further, so I excused myself. When they left, Smokey was clinging to Don’s cotton shirt and several restaurant patrons were nodding in his direction and whispering. But Don had become used to that.

Cherokee, N.C. — It’s difficult to capture the beauty of the Smokey Mountains in words. They stand like majestic guardians between the rolling green of Tennessee and the crashing waves of the Atlantic. Brandon was as fascinated as we were by their very presence.

Just outside of Cherokee on Highway 19 there’s a small white building on the left. I had just turned onto the first straight stretch of highway in 20 miles when the children caught my eye. There were about 40 of them playing, chasing and digging in a large dirt plot beside the building. I found a spot to park the Lady K and walked back.

The event, I discovered from a pretty young woman named Vickey Sanders, was the planting of the annual spring garden at the Soco Day Care and Headstart Center…at least the staff was planting. Vickey, who was the director of the center, said the garden plot measures about 50 by 50 feet. Most of the preschoolers were ignoring the garden in favor of romps through the adjacent grass and rocks.

Surprisingly, the boy described as the class rowdy by Vickey was the only tot hoeing in the garden, and he was plowing as if his noon meal depended on it. When I asked him his name, he said he didn’t have time to talk, there was too much work to do.

I also met a man named Wayne Hornbuckle, the janitor and bus driver for the school. He told me that each of the 36 children there were at least partially Indian. Some were full-blooded Cherokee. Three youngsters climbed inside his wheelbarrow as we talked and there were ten others gathered around him. They obviously cared a lot for Wayne.

He went on to explain that most of the children at Soco come from families who labor in the nearby factories. He drives 20 miles a day to gather the students from communities with such colorful names as Big Y, Wolf Town, Paint Town and Cherokee.

More children gathered around us as we talked. Some asked me to take their pictures, which I did. Others asked who I was and what was I doing. One tiny girl asked me to guess her name and I gave up after reciting every name in the book of female monikers. She never did tell me her name.

Wayne, himself an Indian with blue-black hair and a ruddy complexion, said the largest employers in the area are the Whiteshield Corp. and The Cherokee Corp., which manufactures Indian goods for sale to tourists.

“Matthew, Mark, John,” Vickey cried out above the melee. “It’s time to go to the play yard. All I need now is a Luke and we’d have a full set,” she said with a chuckle. We walked to the playground and she told me the center is funded for nine months by the government and for the other three months by the Cherokee tribe. But the summer sessions are only for the children of working mothers.

I was interested in knowing what the children were fed at Soco. Vickey said they receive enough nutrition at the center to tide them over even if they got nothing at home. Occasionally, they prepare an authentic Indian meal of pinto bean dumplings, sulchan which they pick and prepare and streaked meat (fat back with streaks of lean).

I thanked everyone for their time and walked back to the Lady K. In the background, several of the children were waving goodbye. I waved back and called to them. When the door to the coach swung open, I knew I was in the doghouse with my son. He was mad because I hadn’t taken him along to play. We talked about it for a while and I let him play drive Lady K for a few miles. Before long, all was well and we were back on track for the Atlantic.

BETHEL, N.C. — The tobacco fields of central North Carolina resemble the rambling cotton and soybean tracts of eastern Arkansas. They stretch for great distances across a generally flat landscape, seeming never to and.

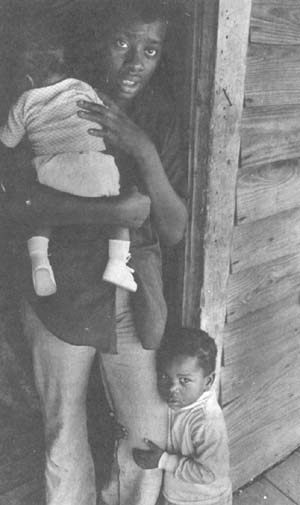

Here, again, were those small, gray board shacks beside the highway. This time I decided to bring the Lady K to a stop and talk to a person or persons behind the door of such a home.

Dottie was 22 and much friendlier than I’d expected. There was a tiny baby cradled in her arms and a small girl continually clung to one leg. A preschool aged boy played in the yard.

She told me her parents were working in the tobacco fields and wouldn’t return until about seven that night. Dottie finished high school in 1972 and had spent a lifetime watching her mother and father leave at daybreak to farm the land.

We sat on the porch to talk about her and her family. She was keeping her own children, which also included an infant asleep inside, in addition to her sister’s child each day. Her sister was still in high school. Dottie has never particularly cared for work in the fields, she said.

The children became more at ease around me as our conversation continued. She also explained that she receives a monthly check from the government for child support.

The house was surrounded on three sides by a tobacco crop and the fourth side faced the highway, about ten yards away. Cars and semi-trailer trucks thundered past while we talked.

At one point she paused, then hesitatingly asked if I would mind taking a picture of her youngest child. There had never been a photo, she said, and she would like more than anything to have one she could frame. We stepped inside the small house. There was a bed on one side and the house was very warm and was not pleasant to smell. The baby was awake and she dabbed at his hair before laying him face down on the bed.

I snapped the photo and promised to send her a print, which I later did. Before leaving, I took another picture at the porch. She smiled and thanked me for stopping by.

Walking back to the Lady K, I felt somewhat empty inside. I wondered what it would be like to work in a tobacco field. Three miles later, I would have that opportunity.

They were a small group of women and one boy on their hands and knees tugging at the green, leafy plants and I decided there was no time like that time to answer my own question. I didn’t have to explain to Kathy. She understood, saying there was plenty to keep her busy while I was gone.

Departing the coach once again, I walked a half-mile to where they were working. Most refused to even look at me. But the boy acknowledged my arrival and I asked if he would teach me how to work the tobacco plants.

Jeff Hine was patient as he explained how the young plants must be pulled out by their roots and placed in the crates for transplanting in another field.

The amiable 15-year-old showed me how to grasp the plant close to the moist earth and yank smoothly to bring the sizeable clump of roots up intact.

The older women cast frequent glances of suspicion over their shoulders as the afternoon progressed. Jeff’s older sister, Joyce, who was 18, soon struck up a conversation about Arkansas and how I might like farming for a living. I told her I thought I’d enjoy being outside, but I could also see it didn’t take long for one’s back to grow weary from stooping to gather acres and acres of those leaves.

Jeff and Joyce were staying out of school to pick tobacco in a field owned by Don Carson Sr., who had about 60 acres of the plants. I later learned that Pitt County, where we were, is one of the largest tobacco producing counties in the nation.

The brother and sister came from a family of six children where farming had been a way of life. Their older sister, Shelia, was also picking tobacco that afternoon, but she remained silent and listened to our discussions.

I was curious about the damp soil, since there had been no rain for several days. Jeff said they water the young fields to make the plants easier to pull.

Also, I noticed the leaves didn’t smell at all like tobacco from a package, Joyce said the familiar aroma doesn’t come until after the smaller plants are resown and grown to several feet tall, then cured in one of the small wooden houses visible in the distance.

The five-acre field was surrounded by a wall of green trees on the horizon. There were other fields that had already been picked surrounding us. A late-Spring sun was making itself felt and it didn’t take long for me to realize that I was indeed laboring.

Jeff and Joyce kept asking if I had lost my mind, and I agreed. They giggled a lot under their breath. Some of the older women just shook their heads on occasion.

There were plastic covers beside each narrow field. Jeff told me they were used to cover the plants in case of frosts that would wilt them quickly. The tobacco is sown, much like grass is, by hand during late February. They aren’t replanted until reaching six to eight inches.

Jeff cut the figure of a real tobacco trouper in his tennis shoes and reversed ball cap. It was his job to haul the loaded boxes to a central point where a pick-up truck would regularly collect them. He laughed when I boasted about the box I had almost filled, pointing to three crates that Joyce had loaded in the same time. Nevertheless, there was a distinct feeling of accomplishment that I refused to deny.

There were small holes in some of the leaves, Joyce said they would be all right if they hadn’t bean eaten by some critter that obviously had not read the warning messages issued by Uncle Sam.

As the afternoon wore on, the three of us became friends and discussed their lives compared to mine. I could tell they were both searching for something more than what we were doing. I didn’t blame them.

By the time I dragged my perspiring body back aboard the Lady K, I’d learned more about tobacco than I’d probably ever use. Kathy had caught up on the record keeping while Brandon was catching up on his sleep. I was a comfortable kind of tired myself.

We drove until I found a spot to turn the coach around and motored slowly back past my afternoon companions. I had a new perspective on the people I’d so often zipped past in my air-conditioned car with tinted glass windshields. I brought the Lady K to a stop on the highway and extended my arm out the window for a final wave. Jeff and Joyce waved and, for the first time that afternoon, several of the older women acknowledged my existence by waving back.

There were small holes in some of the leaves, Joyce said they would be all right if they hadn’t bean eaten by some critter that obviously had not read the warning messages issued by Uncle Sam.

As the afternoon wore on, the three of us became friends and discussed their lives compared to mine. I could tell they were both searching for something more than what we were doing. I didn’t blame them.

By the time I dragged my perspiring body back aboard the Lady K, I’d learned more about tobacco than I’d probably ever use. Kathy had caught up on the record keeping while Brandon was catching up on his sleep. I was a comfortable kind of tired myself.

We drove until I found a spot to turn the coach around and motored slowly back past my afternoon companions. I had a new perspective on the people I’d so often zipped past in my air-conditioned car with tinted glass windshields. I brought the Lady K to a stop on the highway and extended my arm out the window for a final wave. Jeff and Joyce waved and, for the first time that afternoon, several of the older women acknowledged my existence by waving back.

Manchese, N.C. — The Daniels family fishing fleet is moored directly beneath and all around their family restaurant. Kathy and I agreed we had never seen a more picturesque seafood restaurant, especially in such a small town.

We had stopped for two cups of coffee and an orange and before we left, I asked the young man behind the counter who designed and operated the upstairs cafe called Fisherman’s Wharf, His story turned out to be even more interesting than the board building.

It seems there are 15 children in the Daniels family, and they all work either at the restaurant or for the family fishing fleet, which catches everything patrons order on the menu. Downstairs, there was a complete fish, crab, scallop and shrimp processing plant and Mark Daniels, who was 19, agreed to leave his spot behind the counter and take us down for a look.

Beneath, we discovered a world of cranes and conveyor belts and ice and fish scales. Mark pointed out various brothers as we toured the plant. He said the family has a fleet of nine boats, the largest and newest of which cost only $150,000. Two are named after sisters.

Most of the seafood restaurants in the area are served by the Daniels, fleet, he said. The only item they import is lobsters.

In the refrigerator room, there was a mountain of ice in one corner waiting to be loaded onto an outgoing ship. On the other side were about seven boxes of soft-shell crabs. The crate lids were open and the crabs were neatly lined up as though in formation. One moved. Kathy screamed. Mark said they were still alive and would be shipped that way. For some reason, they don’t move around after being placed in the boxes. Brandon felt one and said “ugh, they’re like rubber.”

The Daniels live in the largest house in Manchese out of necessity. Mark told me it has nine bedrooms. He also said his father began in the ice business and purchased the property we were on after saving for several years. Prom that point, business flourished and he branched out into a full-fledged fishing fleet. They added the restaurant above the processing plant about two years ago.

The story of catching fish from the sea and preparing them for human consumption was a fascinating one to Kathy and me. Coming from a landlocked state, this was a new experience. Brandon liked the large, masted boats and the smell of the docks and diesel fuel mingled with salt.

Mark excused himself to return to the restaurant, but before he left, I asked if he planned on spending his life at Fisherman’s Wharf with the family. He said he was going to a Bible college in Florida to become a missionary to children.

We had decided to head northward into Virginia and Williamsburg would be the next stop…

May 20, 1976

©1976 Mike Masterson

Mike Masterson is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Sentinel Record (Hot Springs, Arkansas). Mr. Masterson will travel throughout the U.S. with his family and write about the country and its people in 1976. This article may be published with credit to The Sentinel Record and to Mr. Masterson as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.