Williamsburg, Va. — In blissful inexperience we rolled out of Cape Hatteras, N.C., only half heeding the warnings about “endless strings of toll roads and bridges up north.” A few miles later we received our financial baptism to Bicentennialand.

A pretty young miss seated on a park picnic table in Williamsburg, told me prices had almost doubled there since May…in observance, no doubt, of 200 years of independence.

We had hoped to spend that night out of the Lady K, but the 16-year-old miss named Jody said most rooms in town, including the motel she was being paid to tout beside a sign marked “hotel information,” had climbed to about $28 nightly for a couple. We sought out a campground and nestled in for three days.

Williamsburg seemed to me to be a good example of what can be done to attract tourists without throwing up a hot dog stand and a ferris wheel. The rustic cobblestone streets and brick buildings helped all three of us to actually feel part of what happened there 200 years ago. Of course, I was continually reminded by those around town that Rockefeller money was the seed from whence that restored colonial flower blossomed.

Enjoying as much of Williamsburg as we could afford, we crammed everything back into drawers and beneath seats then aimed our noses in a northerly direction.

It was surprising to discover much of the roadside greenery of the heavily urbanized states like New York and New Jersey bore striking resemblance to forested areas of the South.

Despite enjoying the unexpected scenery, there was noticeable frustration mounting within all three of us as we breezed northward doling out half dollars at one tollbooth after another. Like lobsters held by their tails above a boiling kettle, we began to realize we were dropping ourselves into a seething megalopolis preferably avoided.

A day’s accounting showed we once paid tolls totaling $7.35 in less than 200 miles. There was also a bridge we believe New Yorkers are particularly proud of, since they charged us $4.20 just to cross it one time. The salt in the sore was that very few toll clerks even returned a smile with the change. The only one who ever spoke did so in order to throw us off the Garden State Parkway in New Jersey for having the audacity to attach a car behind the Lady K. Kathy said she thought it was because I hadn’t used mouthwash that day.

We did survive the megalopolis, which included Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, New Jersey and New York, then paused to lick our emotional and financial wounds in the rustic seaport village of Mystic, Connecticut.

Mystic is a storybook community with spanking white houses, tall, masted ships, a small drawbridge and a quaint chiming church standing sentry-like, over the historical downtown buildings. It’s also a town that residents claim people can’t leave for long. “Yep,” said one elderly man taking a long draw from his pipe, “folks might leave here, but something always draws them back.”

Whatever it was, we could sense it, too. There is something calming to the soul in that former whaling village.

One evening while in Mystic, Kathy and I gathered a pile of wood and built a roaring fire to sit beside and reflect on what we had seen amid the melee of the urban sprawl.

I envisioned an 18-year-old named Ann Carson, sparkle-eyed and filled with unbridled enthusiasm, whom we had met selling doughnuts at a shopping mall in Wilmington, Delaware. She was to graduate from Concord High School the following evening and, as she sacked our order, I had mentally stored her conversation about a course she had taken as a senior.

The class, entitled futurology, was taught by an instructor who opened by stating flatly that mankind has become a virtual slave to his technology and machines. The teacher used examples of automobiles, television sets, washing machines and the influence of mass media over public opinion.

“At first,” Ann told me, “several disagreed with him, including me. But by the end of the course, we saw he was right. Things just seem to be moving too fast. The daughter of a Wilmington psychiatrist said she planned to attend college next year and study…computer science.”

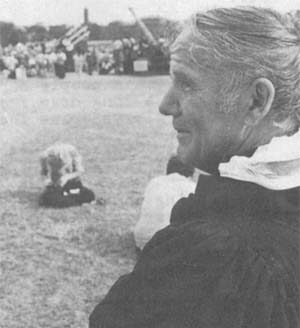

Kathy reminded me of the afternoon we had spent on the undulating green lawn beneath the Washington Monument, and of a 56-year-old, black-robed John Schiel, who had stood for six hours as the specter of death in a protest against “wasting money on military weapons.”

John was a slightly-built, congenial fellow who had once studied in a Catholic seminary. From him I learned that protestors can come in all shapes and ages. He also showed me there are still people who have convictions strong enough to endure ridicule for what they believe. During his afternoon on the lawn, he had been cursed and called names by several people.

He was representing a group called the Committee of Creative Nonviolence and he repeatedly said he had nothing to hide from anyone. I told him I had to admire anyone who would don a Black Death costume with a white facemask on a hot day and spend a weekend absorbing assorted rebuffs.

He shrugged and scratched his head. “I was arrested on Good Friday for reading scripture in front of the Pentagon,” he said. “When the case got to court, the judge dismissed it immediately and he told the police that people in America still have the right to free speech and peaceful assembly to show how we feel.”

As the man spoke, a military band at the nearby armed forces show struck up a rousing Sousa march. Children were squealing with delight as they climbed all over a long-range cannon on display behind him. John sighed one of those…it’s a long struggle…type sighs and dropped his gaze to the ground. Brandon was one of the youngsters crawling on the Howitzer. He was pretending to shoot down the Monument.

I rose to toss another log on the fire and Kathy went inside to put Brandon down for the evening. When she returned, I was sitting again, staring into the leaping flames…continuing to ponder our travels to that point.

We had seen evidence in several towns like Memphis, Tennessee, and many even smaller, of a struggle to maintain downtown businesses as viable competitors to the mushrooming shopping malls that seem to be springing up in even the smallest of cities. The technique is to turn a downtown area into a walking mall, spending tens of thousands of dollars to try to keep the inner city thriving. The basic idea seems to be a good one, but I talked with a number of skeptical people who said high crime rates and suburban living have sounded the death knell for their downtown areas, in addition to inconvenience with such things as parking. It will be interesting to see what effect these inner city malls will have a decade hence.

Much of what we had experienced in the eastern megalopolis I felt reflected the inability of people in that area to effectively communicate with each other. For instance, our two atlases and CB radio were little help in attempting to understand the confusing highway signs. We found ourselves lost time after time.

There were friendly people in the urban confusion. But there were also many who seemed to have insulated themselves to the point of abrasiveness and rudeness…afraid to let their defenses down…always ready with a scowl to get the first lick in. They were the ones who dared not reveal even a tiny portion of themselves for fear of physical or emotional pain.

Money and speed were masters in this stretch of asphalt and stone. People honk if you don’t zoom away from stoplights. Parking tickets are $25. It cost us $6 just to drive into downtown New York and turn the key off. Everywhere in these behemoth cities you can see the blank expressions moving at a three fourths run toward rumbling, foul-smelling holes in the ground, holes that will take them back home again so they can return the next day to repeat the performance and draw the monthly salary. I wondered aloud to Kathy what life must mean for these hundreds of thousands of human beings. Maybe there is fulfillment in such callous places. But I suspect gratification is, by and large, colored green. The megalopolis was not a compassionate place through these eyes.

Kathy and I agreed that the hostility and anxiety generated in those cities is a crawling, contagious affliction capable of dampening the most optimistic of spirits. The two of us contracted that defensive disease for a time and found ourselves frequently at each other’s throats over petty matters, but the loathsome scourge passed and we managed to regain our equilibrium in Mystic.

Philadelphia, Pa. — The skyline of this Bicentennial city loomed on the horizon as the Lady K sped toward the heart of those man-made peaks. In normal fashion, I made a wrong turn and we found ourselves edging down a narrow residential street with only inches to spare on each side between the parked cars.

For seemingly endless blocks the solid rows of connected, three-story dwellings continued with only sidewalks for yards. Children played in the streets because that was all they had. A desperation call on the CB brought help in the form of a housewife in a late-model car who guided us out of the neighborhoods to a motel. We talked on the radio to the thoroughfare and she told me the houses we had passed sold for between $35,000 and $40,000. In the South, I supposed the same dilapidated structures would have been half that much, or less.

We did find a motel and after hauling assorted clothing, toys and other necessities into the room, we left to join the waiting throngs of Liberty Bell massagers.

I winced a bit, as did Kathy, when we noticed a lock on the outside doors to the motel and TV cameras like the ones inside banks watching us. The only way inside the motel was to ring a buzzer and wait for the cashier to examine us before she released the lock. We knew we had reached the urban sprawl.

Standing amid the hundreds of other potential Bell fondlers, I began to feel somewhat silly. I wondered if others around me were asking themselves if this was really what they wanted to be doing. Watching the hands and fingers groping for a quick feel, the thought struck me that somewhere in the red-brick Independence Square, there is bound to be a person whose job it is to keep that bell clean. A guard told me I’d have to walk to the East Wing and see Louise Boggs, which I did. Thirty minutes later, we were sitting in her basement office, surrounded by a maze of hissing and clanging, steam pipes.

The attractive mother of seven children sat behind her vintage roll-top desk and explained how she began her career with the National Park Service as a cleaning woman more than 20 years ago. Today, she is the maintenance supervisor for Independence Square and responsible for the cleaning efforts of 30 men and woman.

In the beginning years, her job was equally demanding, but in a different way. “There were originally five of us women to keep all the historical buildings clean,” she said. Four years ago, she was promoted to supervisor and she said the administrative details keep her just as active.

Part of her responsibility as a cleaning woman was to polish the Liberty Bell at least five times a day, using a cheesecloth substance and a double dose of elbow grease.

Louise leaned back in the chair and chuckled a bit while recalling her technique for wading through the masses to do her job. “I’d ask the people to please bear with me while I cleaned the bell. I had a job to do and most folks understood that, but there were always a few who’d shove up and get a feel in when I was trying to get done.”

“I’d just step back and tell them to go ahead. I always tried to be friendly…”

I soon discovered that the buildings where freedom’s trickle became a gusher meant far more to Louise than floors to shine and walls to scrub. Within her, I detected a fervid dedication to that small section of Philadelphia.

“There’s something sacred to me about these grounds,” she said. “Why, on the night they moved the Liberty Bell from Independence Hall to the new viewing building, there came the worst storm we’ve ever seen here. I mean it was hailing, thundering, lightning, raining and about everything else.”

“It made a lot of people wonder if we should have been moving our bell. Despite the storm, do you know there were 10,000 people who showed up to watch that New Year’s Eve night? The bell has special meaning to a lot of people.”

Clad in her dark-green work uniform, the articulate woman continued to spearhead the cleaning operations over a walkie-talkie while we visited. I asked if the surrounding steam pipes and gauges bothered her and she grinned, “Not at all, I’ve gotten used to being down here. I don’t even notice it anymore.”

Her husband, a Philadelphia cab driver, might retire soon, she said, but she plans to stay right there beneath the historic East Wing building for as long as she can.

Overhead, we could hear the sounds of another 80 tourists being herded into an overhead room for an orientation film about the Square and the grounds. I stood to thank Louise Boggs for her time and, as I did, I wondered how many of the sightseers above would see the product of her handiwork that day, but never give it a second thought. There was no doubt in my mind that Louise and her staff of 30, like so many other Americans, were locked into jobs where recognition for hard work and loyalty comes only in the form of a paycheck.

We spent two days in Philadelphia and before we escaped, a television newscast led us to something called the outdoor Italian Market, I had never seen or smelled anything like it before.

The warm afternoon was literally alive with cries from multitudes of anxious vendors. Small sidewalk stands began immediately in front of us lined up side by side as they sprawled to the horizon of a narrow Ninth Street downtown.

Mingled aromas of assorted fruits, fowl and the drippings from freshly caught fish rode a breeze that whipped between the buildings and teased the nostrils of passers-by.

I stopped for a moment and closed my eyes to listen. There were sounds of men and women shouting their goods in wailing chants, the clanging of cash registers, horns honking people talking, bicycle bells chiming, dogs barking, a jet plane overhead…it was alive with bustling humanity from at least five nationalities.

Brandon was fascinated by one peddler’s display of fish, squid, and octopus. He also demanded, in five-year-old fashion, that every denizen be correctly identified.

Kathy swore a blood oath that if we lived in Philadelphia, she’d be a regular face along Ninth St., buying tractor-trailer loads of fresh fruit and vegetables.

An interesting fellow with a swarthy complexion and closely cropped mustache was bellowing an unintelligible phrase at the top of his lungs. I stopped and asked what he was yelling. He politely informed me he was yelling his produce.

In the conversation that followed, I discovered he was Anthony Messina, a 48-year-old bachelor who said he had worked in the market since he was six. The stand once belonged to his father.

His wooden booths held a bounty of vegetables and fruits displayed on both sides of the walkway.

After a few minutes, he asked me to call him Tony and while he bagged lettuce, corn and peppers, I learned he rises everyday at 4 a.m. to drive his pick-up three miles to the produce wholesale market where he engages in the daily bartering war for the produce he’ll sell that day.

He’s generally back to Ninth Street and his stand by 6:30 a.m., where he frantically begins sorting his wares for the day’s shoppers, who often arrive by 7:30 a.m. This goes on, he told me, for five days a week. Some merchants on Ninth Street endure the ordeal six times a week.

A younger man, whom Tony called Fonzie, was working beside him. “I call him Fonzie, because he looks, like the Fonz on television, eh?” Tony raised his eyebrows and smiled. I agreed, but found out later, the 19-year-old boy’s name was actually Freddie.

The rambunctious Italian said, despite the fact that the Italian Market is probably the largest open-air market in America, he doesn’t expect the influx of Bicentennial worshippers to boost sales on Ninth Street. “Hey,” he said, “how many tourists you know gonna take a squash and a potato back to their rooms with them? We’ll have a lot of lookers, but I don’t think it will help us much.”

We spent five short hours amid the six or seven blocks of the market, meeting such friendly merchants as Salvatore De Nicola, a 53-year-old father of two who stood smiling behind a mountain of hen eggs and cages full of hens, turkeys, and ducks. There were the good-natured Pino brothers…Pete, Nick and Frank who, like Tony, inherited their produce stand from their father and grew up working there.

Mr. and Mrs. So Kie Chung stood in front of their leather goods store talking among themselves. They took a moment to tell me they’re expecting their first child in ‘August. The Chung’s purchased the store about two years ago and have managed to make a success of it.

If it hadn’t been for a strong wind, that forced us back to the car, we might still be there…Kathy said she thought I’d make an exceptional cod peddler. Brandon said he wanted to open a candy and ice cream stand.

I did feel that there, amid all those tables and produce, we were getting a first-hand look at a vanishing part of this nation; the part where a small, independent merchant can still put in a day’s work in his or her own enterprise and earn enough coins to keep a home and family together. The market and those people were a classic example of free enterprise in action.

That night, in the confines of our television-supervised, double-looked, ultra lighted room, we decided to make our escape from Philadelphia by early morning’s light and somehow find our way to the harmonious city of Boston, where we imagined the doors would probably have triple locks.

Boston, Mass. — If I could prepare an American stew, tossing in people of almost every race, political bent and age, laced with a smattering of bizarre and dash of mania, then stirring well while it simmered over a warm summer’s day, the end result would be the Boston Common.

I shared the Common experience, with Brandon, since Kathy had flown to Arkansas following a sudden death in the family.

With a frisbee and notebook beneath our arms, we entered a Saturday morning crowd gawking in typical, country-boys fashion. The acres of closely-cropped grass, reminded me of plush parks in many other cities and towns. There

were gently rolling green knolls speckled with sunlight that filtered through openings between leaves of hundreds of tall shade trees. The park, in the heart of downtown Boston, was surrounded by a wide sidewalk where teeming humanity swayed to and fro.

Dozens of vagabond musicians sporting guitars, accordions and harmonicas were trading songs for dimes and quarters tossed by passers-by into empty instrument cases.

Pausing on the concrete pathway, we watched a tattooed sword swallower who fascinated Brandon so much, that he dug in his pocket for the dime held been saving for ice cream.

After his act, I asked the fellow who called himself Captain Don Leslie about his life.

He said he was formerly with Ringling Bros. for 20 years where held been billed as the tattooed man who swallowed swords and walked on nails. He told me he began his career as a young boy when he ran away to join the circus.

As we talked, his young boys circulated among the surrounding crowd for contributions, while his wife, Jo Anne, sat behind us in the grass. I asked a little later how she felt about Don baring his chest and swallowing swords on the sidewalks for a living. She smiled and answered, “I’m proud of him. He’s earning his way.”

Strolling through the paved walkways, covered by overhanging shade trees, we saw and heard people conversing about everything from philosophy to busing to baby sitting.

One girl asked me to sign a petition to ban no-return soft drink bottles in Massachusetts. I told her I thought it was a good idea, but, as nomads, neither my signature nor Brandon’s could help the cause.

The metallic clang of a tambourine in motion accompanied by the thump of a bongo drum and the familiar Hare Krishna chant was distinguishable amid a blending of assorted songs and melodies being strummed and hummed around us.

It was Brandon’s first introduction to public performances by the Krishnas. He stood close by my side in fascination with the chanting trio of shaved heads who were clad in light orange robes.

To one side, a middle-aged ice cream vendor was openly mocking the worshippers with a hearty laugh while twisting an Irish fling to their music.

Boys on skateboards weaved, sometimes at great speeds, between people in the park. There were also the pathetically familiar derelicts; some wandering in aimless stupors while others rifled the trash for an uneaten sandwich crust.

If there was racial trouble in Boston that day it was not apparent on the Boston Common. Black and white children and adults talked and played together. The only evidence of closed minds I saw, was a poorly-scrawled message on the outside of a men’s room that said ““n…..” heaven”.

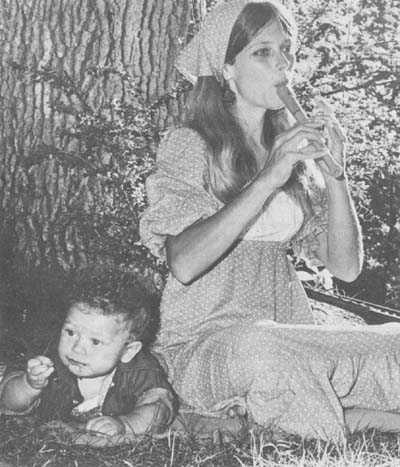

We talked to several people during the day, but the most interesting was a 36-year-old folk singer who called herself Ruth Anna.

A handful of people were clustered about the long-haired woman with soft features when a gusting breeze carried our wayward frisbee to within ear shot of her music.

Ruth Anna, and her 15-month-old son, Joseph, were seated beneath the protective leaves of a massive shade tree. She was singing about her parents in Colorado. We drew closer to listen. The words told a tale of love and of a family who settled on the slopes of the Rocky Mountains to farm away their lives in happiness. She also sang about how much she owed them for allowing her to be herself and to live her own life without having to live up to their likes and dislikes.

After that song, a few people dropped quarters and dollars unto a black vinyl case, including Brandon, who had “borrowed” a quarter, and she thanked them with a smile, saying she wouldn’t be singing anymore that day.

Beside her, Joseph was playing in the dirt. Around him were his mother’s other instruments, including a wooden flute.

I asked if we might talk for a while and she motioned for me to sit beside her. One thing most strikingly handsome to me was her son’s creamy complexion and black curly hair.

Ruth Anna, who it seems had developed a regional reputation for her music through weekly radio programs, concerts, and her days on the Common, said Joseph’s complexion was easily explainable.

“His father is black. I’m an unmarried mother,” she said with a smile. “Joseph’s father, Abdullah, was a musician who I played my songs with for a while. The more I knew Abdullah the more I realized I wanted to have his baby. So I did.”

Ruth Anna went on to explain how an earlier marriage had failed after she and her husband, who had both been in the Peace Corps, returned to the United States.

“I was a school teacher then,” she said, “and I realized I really wasn’t fulfilled or happy with my life. I’ve been playing music since I was eleven and I knew there was fulfillment for me in that.”

Brandon played with Joseph while we continued to talk, interrupted frequently by her admirers and well-wishers. She told me her mother and father have accepted Joseph and her free-wheeling, no strings, life style. “They love Joseph and want to see him every chance they can. Both of my parents have been positive influences in my life rather than negative ones and I love them for their understanding.”

In the mid 1960’s when flower children were blooming in backyards everywhere Ruth Anna counted herself one of the bouquet. She traveled to Boston to play her music.

Soon afterwards, she said she’d traveled with two young men to a street dance in Canada where an agent for a large recording firm heard her songs and asked her to audition for a possible record. “Everyone was telling me I had been discovered,” she said, “but after I sang for them, they said my songs weren’t commercial enough.”

It was also during her years as a flower child that Ruth Anna said she learned cruelty and evil in people can’t always be vanquished with a mere smile and the offer of a freshly-plucked dandelion. Shortly after her divorce, two men in Colorado took her by force to an isolated road and raped her in their pickup truck. “All I could think about was just staying alive, she said. “Up until then, I had always thought a smile was enough to disarm anyone with evil intentions.”

The two men were arrested shortly after the incident but, since she was an admitted child of the flower cult, she was urged by friends to drop the charges, lest she be emotionally quartered in a public courtroom.

Joseph has brought a purpose to life for Ruth Anna. She thrives on the baby’s very existence and says they have a relationship of complete openness and sharing. “Joseph and my music are my existence,” she said. “I strive to reach him every day and to reach other human beings with a message through my music, too.”

“You know,” she continued, “it’s strange the way people sometimes speak of freedom and the right to do your own thing, but then turn around to criticize or condemn a person if he or she doesn’t do what’s expected or accepted.”

“Like, I really wanted to have Joseph, so I had him. I couldn’t be happier. Most of the people who know me understand that and have accepted us. Those who can’t accept, have to face it as their own problem.”

I helped Ruth Anna into her tattered canvas baby-tote and sat Joseph inside.

An elderly man stopped to hug her. She later said that he comes to hear her when she sings on the Common twice each week.

Across the expanse of Kelley green I could hear a flute and calypso drums beating out a Jamaican rhythm. Ruth Anna’s face brightened in a broad smile. “It’s Abdullah,” she said in a whisper, “Come here,” she motioned toward me, “I want you to hear the music that inspired Joseph’s birth.”

Brandon and I strolled with her to a large, mostly-black gathering where two perspiring hand drummers labored furiously over their instruments and the shrill notes of a flute in the hands of Joseph’s father sailed high above the rumbling.

Uninhibited…oblivious to anyone else, the barefooted woman stepped in front of the drummers with Joseph on board, closed her eyes, and began to twirl and sway to the music. I watched Abdullah follow her with his eyes and smile at Joseph behind the instrument, and I recalled words from an earlier conversation. “Abdullah and I seldom see each other. He’d like to get married I know, but I’m not sure that’s what I want. I have Joseph and my life is complete. He has his life and I have mine.”

When Brandon and I left the Common that day, we decided to eat dinner at an Irish restaurant in downtown South Boston; I suppose just to be able to say we had. We later agreed, in a man-to-man conversation, that the best part of the day was 10:02 p.m. when a roaring, smoking American Airlines jet brought Kathy back to our home on wheels.

Bangor, Maine — Maine has always appeared to me on maps as a cold, rugged appendage set virtually adrift from mainstream America, connected by a few concrete ribbons which hold it fast.

Those preconceptions included a people whose nature matched the long, cold winters, but, as is the case with most preconceptions, mine were proven shamefully wrong.

Entering at the southernmost tip, we rolled the Lady K along U.S. Highway 1, not expecting to encounter the gentle hills that formed a stark contrast to the brawny, sculptured coastline. Neither had we known how heavily that state’s economy relies on the potatoes that spring from the nurtured soil of Aroostook County to the north. The landscape from the crashing breakers and lobster piers of Bar Harbor to Aroostook can be compared to the differences in walking from a den into the kitchen. Terrain evolves from glacial granite and towering mountains alive with white birch and spruce to brown-striped swells of earth.

During our stay regional media were filled with stories about the local Communist Party’s attempt to appear on the ballot of an upcoming election. It seems about 13,000 residents had signed a petition which would have permitted that Party’s candidate to be listed. But the petition was being challenged by one official who said he couldn’t believe there were 13,000 Communists in Maine. Another official had responded by saying the petition signers weren’t necessarily Communists, they simply had been saying the Party had a right to appear.

Most of those we asked about the issue agreed with the petition-signers, strictly on the basis of freedom of choice and the right to be heard.

Although awe-inspiring scenery and environment provide the mortar for the house of Maine, I discovered that state’s people are the bricks, tempered in a kiln of tenacity.

That observation was reinforced by Bill and Doris McDougal, of Bangor, who invited us to their home late one night where we hovered over a tub of steamed clams and listened to anecdotes about stamina and sacrifice.

The McDougals, who own and operate the KOA campground where we had parked Lady K, are natives of Maine. In between gigantic gulps of cold beer and mouthfuls of the tasty mollusks, they spoke of days gone by, days when Doris picked 87 barrels of potatoes in the fields up north, days when the odds seemed overwhelmingly stacked against them…yet they persisted.

It was refreshing to find there are still many people in this country who have a knack for genuinely making others feel a part of their lives. The McDougals are just such human beings with everyone they meet. The three days we spent in Bangor proved fruitful in a variety of ways, but the sweetest of the fruit was what we learned from that couple.

One point Bill doggedly stressed about Maine was “rugged individualism,” a reputed inborn ability of the people there for survival despite the ever-present hurdles of foul weather, a short growing season and relatively limited industry.

Seeking our own evidence of this quality, we piled enough for an overnight stay into the Honda and started northward on a 440-mile round trip to the extreme upper reaches of Aroostook and America.

Aroostook somewhat resembles the neatly plowed croplands along the Mississippi River delta, except for rolling topography. The towns became smaller and farther apart as we climbed upward. There were hundreds of classic barns over the rises and homes looked as though they had emerged victorious from each of a thousand skirmishes. There were also imaginatively named communities such as Presque Isle, Millinocket, Mars Hill and where we finally stopped for the night in Caribou.

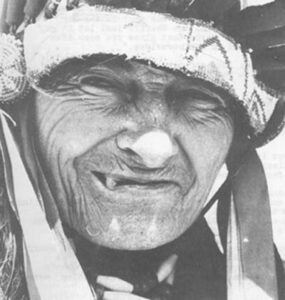

Mars Hill, Maine — The next morning, three miles north of this town on U.S. 1, we spent the day with as good an example of rugged individualism as I have ever known.

Actually, discovering the Dan Buckley clan was mostly an accident. We probably would have passed by their small, weather-beaten frame home without so much as a second glance if it hadn’t been for a school bus that was stopped to feed eight children into the roadside dwelling.

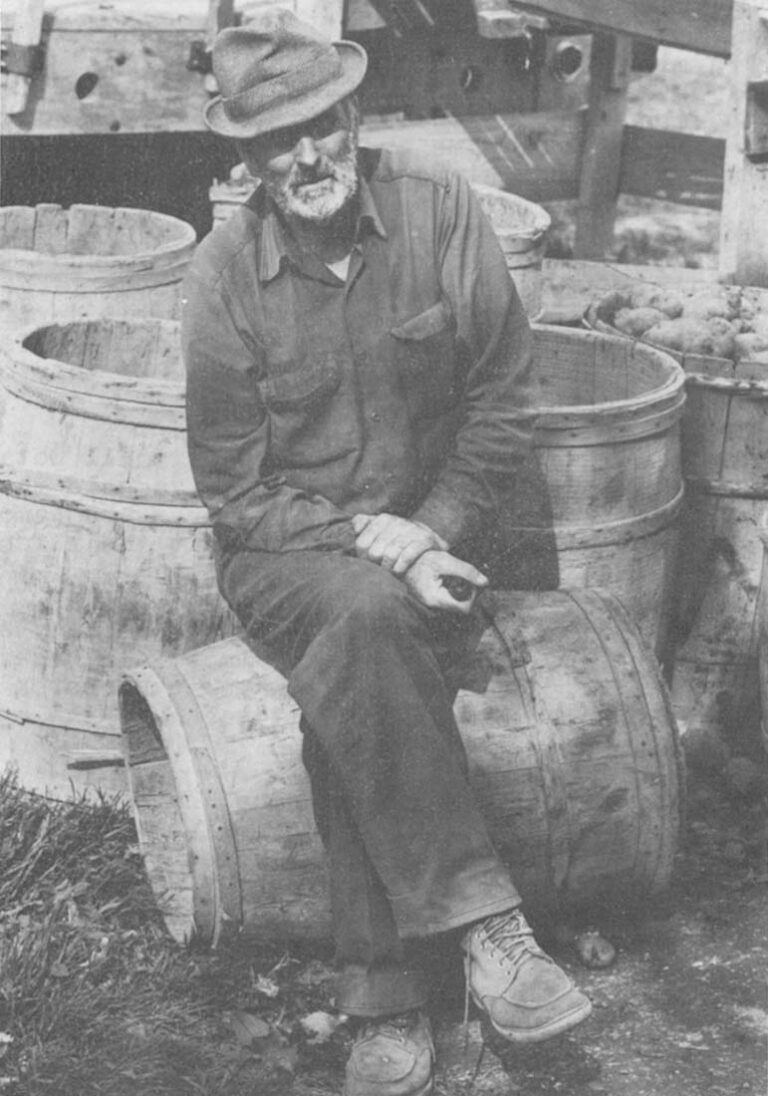

The closer I looked, the more I could tell that these people, whatever else they might be, were survivors. Freshly plowed and planted fields stood on three sides of the red house. Wooden barrels stacked beside the home surrounded an odd-looking machine which was chewing whole potatoes like Brandon devours a bag of popcorn.

Overcoming an initial cowardly impulse to drive on, I whipped off the road and pulled to a stop in front of the house. Before I could get to the front door, an elderly man with tussled hair, a three-day beard and a well-chewed pipe appeared from behind and motioned me inside.

Dan Buckley II, I later learned there are four Dan Buckleys in the family, asked me to sit beside him in a tiny, but comfortable, living room where we were immediately encircled by children, dogs and at least 100 friendly house flies. There, he related a story about Irish origins and a family who had lived off the land for more than 100 years.

His grandfather, he said, began raising potatoes near where the present Buckley house now stands during the mid 1870’s. Buckley’s father, Dan, built the house, then left 100-plus acres to Dan II, whose sons and grandsons have maintained the tradition by continuing to farm the land.

The house is heated by a wood-burning iron stove, as are many in that part of Aroostook, in order to combat the rising cost of heating oil. They also do most of their cooking over that antique appliance. It was not a pretty house to look at. Paint was flaking on every side and years of hard living had taken their toll on window and doorframes, along with the porch and roof. “It might not look like much, by golly, but it’s bought and paid for and that’s saying something. It’s all ours,” said Dan.

I listened in silence while, between violent coughing spasms wrought by the ravages of emphysema. Dan explained how insecure the economic life of a Maine potato farmer can be.

“Farming potatoes is like tossing dice,” he said. “There’ve been a number of years when the crop failed on me and I had to travel down to Connecticut to find work for the winter so’s we all wouldn’t starve up here. I’d send the money back home and when planting time rolled around again, I’d get back here and get back to rattling those dice again.”

The colorful farmer said he was deeply troubled about the future of potato farming in Aroostook County because the few smaller farmers who remain are being rapidly bought out by large, conglomerate-type concerns. “Mark my words young fellow,” he said, darting the stem of his pipe at me, “When that day gets here, those big fellas will tell you what you’ll pay for potatoes if you want them. If they can’t get their price, they just dump them.”

There were once large numbers of small potato farmers who lived all around the Buckleys. One by one I they have sold the farms until now the strong willed family and their 160 acres are among a minority of hold outs who vow they’ll never give up what their families have worked for decades to preserve.

“Now, with the smaller farmer, it was always where he’d have to unload his potatoes as he got them almost, in order to keep up with operating expenses…so there was always potatoes on the market. The corporations will be able to hold the potatoes off the market for as long as they want…until you pay their price.”

Dan II and his wife, Katherine, have raised four children. There are now 12 grandchildren, ten of whom live with and beside them. One son, Frank, and his wife, Kathy, recently returned to the farm from Connecticut where Frank had left a good-paying job with the Connecticut Power Company. He told me he gave up those seven years because he couldn’t stand the pressures and demands of the “rat race” any longer.

As the day wore on, Kathy visited with the women of the Buckley household. Brandon joined the hoard of youngsters in a potato-throwing fight and, after explaining the basics of potato farming, Dan II and Frank snatched a handful of worms from beneath a decayed log and took me to a nearby stream where we reeled in three shimmering brook trout.

While expertly flicking one of the night crawlers into the mirror like pool, Dan also shared a few of his feelings and concerns about America. “We’ve worked hard all our lives,” he said, “which is more than I can say for a lot of folks. I’m afraid things aren’t going to stay like they’ve been in this country. It seems to be getting worse. I believe the next President of the nation will be the force that decides what’s to come for an awful long time.”

“There doesn’t seem to be much integrity around anymore. Maybe it’s been like this all along and we’re just now finding out about it, but it’s shaking the very foundation of what we were founded on, honesty.”

He said his father was the chairman of the Town Democratic Committee for many years and, after his death, Dan II was appointed to the position he continues to hold today. But he was quick to add that he votes for the person rather than the Party.

Like the McDougals, the Buckleys displayed a capacity for warmth and sincerity. They opened their doors and lives to three strangers who appeared from over an asphalt rise beside field number two.

Hardened yet flexible people, they were ready to arch their backs in toil or stop to invite a fellow human in for a cold beer at a moment’s notice.

They had weathered the worst ole Father Maine could muster in a century…and lived to laugh about it.

I say Father Maine because I’m convinced if God had intended for states to have gender, the state of Maine would stand six-foot-six with wide, burly shoulders and the endurance of a full-grown spruce.

We could have stayed longer, but we were into our eighth day already and other states waited. The slogan on New Hampshire license plates reads “Live Free or Die.” I wanted to get acquainted with a New Hampshire town.

Whitefield, N.H. — Most states put simple slogans on their license plates, phrases like Green Mountain State or Garden State or, as in the case of Arkansas, Land of Opportunity, but New Hampshire has elected to make a strong political statement on the tail of each resident’s car. “Live Free or Die,” they tell the rest of us.

It was this spirit I was seeking as we navigated the winding highways within that state’s northern panhandle. As in Maine, we were surprised to see a wide-ranging rural quality in New Hampshire. One attendant at a gas station told me there are only about 400,000 people in the state and most of those live in the southern half. He also said there are a number of poverty pockets in that New England area. It was obvious to us that the impressive White Mountains were more than enough to attract tourist dollars, but we saw very little industry evident in the communities while roiling through. I frequently took the CB in hand to ask local residents about the economy of their particular community. Most responded by saying there were one or two substantial employers in town.

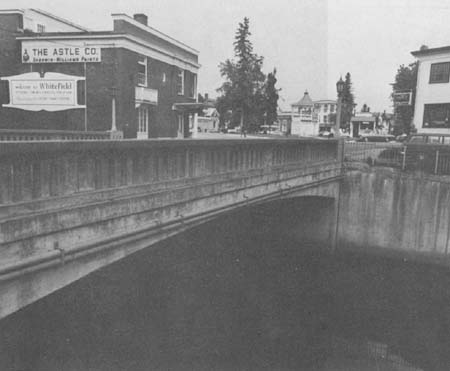

One of those towns was Whitefield, a picturesque village that 1800 people call home. It could be called a fantasy-like hamlet, complete with a flower-covered bandstand in the downtown square and a city hall that could pass for an historic church.

We had stopped at a service station to feed the Lady K her daily 30-gallon portion of motion lotion when Kathy noticed a sign in the station window. It said they would be closing early the next two nights so they could attend “Keith’s graduation.” It was an apologetic message, but we also sensed a bit of hidden pride in the announcement.

Staring through the windshield, I wondered about that little town…where it came from? Who made the decisions there today? What sort of people spent their lives there? Before I could curb the rising curiosity, it had taken a firm hold and I couldn’t turn the ignition key until I had answered some of my own questions.

Records in the small Whitefield Library, said the charter of land known as “Whitefields” was granted on July 4, 1774, to a man named Josiah Moody and a large band of proprietors from Massachusetts. But it wasn’t until 1802 that anyone began clearing land for a settlement. By 1810, there had been only 51 people in Whitefield. Taxes for the entire town in 1818 amounted to only $270.

Asa King was prominent in the history of Whitefield. He was the first to erect a grist mill there and the first school teacher was a gent named Priest Catlin who came in 1805 to deal out the three R’s for 96 cents a week.

The Johns River, flowing through the town, provided lifeblood that kept Whitefield from withering. During the Civil War, mills became more plentiful along the river. But again, it was Asa King who pumped fresh air into the economic coals when, in 1850, he opened and operated the first roadside tavern. Bill Dodge, another name from Whitefield’s past, started the town’s first store in the mid-1850’s and local historians say his establishment became the social center of the area.

With industrial and business growth well underway, it was still dawn-to-dusk subsistence agriculture that prevailed until the Brown brothers, Alson and Warren, set up the Brown Company, which soon became the largest lumber mill in the state. Whitefield was booming with hundreds of workers employed during a period right after the Civil War. The successful businesses attracted others, as well as new faces in the employment lines. Several smaller lumber companies sprouted in the area along with a garment factory and, finally, the Whitefield Savings Bank and Trust Company in 1891.

But Whitefield’s rising star dimmed and faded even faster than it had climbed during those 50 exciting years and the dawn of the 20th Century saw the closing of Brown Company and a thriving dairy industry thwarted when the Borden Creamery burned to the ground in 1908 and wasn’t rebuilt.

Reading further, I realized Whitefield had experienced one unfortunate set of events after another. Just when it appeared things would begin to pick up, residents found themselves facing unexpected calamity and surviving to overcome it.

From the library, I went to Town Hall, where Fire Chief W. A. Placey told me about how things are, from his point of view, in Whitefield today. Placey, it seems, gained a measure of local fame last year when he rose in the annual town meeting and made an impassioned plea, using Lincoln’s freeing of the slaves as an example, against adoption of a local leash law.

Placey had argued that dogs should have the same rights as the slaves who were freed. A woman had then stood to rebuff him by saying the slaves never defecated on people’s lawns. In the end, the “biggest decision to hit Whitefield in a decade” was in favor of a leash law.

Placey, still scrapping, had a cartoon rendering of a leashed dog tugging to get at a fire hydrant being cuddled by a loose kitten published on the back of his annual report of the Village Fire District. He said it caused several superiors to become visibly upset.

In talking with people through the town, I found Whitefield is not governed by a Mayor or Council, but rather by three elected Selectmen who serve revolving three-year terms. The community holds an “all-come” town meeting in March, when town problems are thrashed out and new Selectment voted on…and everyone in Whitefield does come.

The small business area is spotless, thanks primarily to the efforts of a robust Irish man named Edward Quigly, who came from Dublin three years ago and today works for the city collecting trash that finds its way onto local streets and planting flowers around the village green.

There were a surprising number of younger people sitting in the common, around the bandstand that provides a setting for weekly summer concerts. A banner in the park said the Whitefield Lion’s Club would sponsor pancake breakfasts on designated days in July and August and a community bulletin board that sits beside Frank Puglisi’s clothing store says someone has free kittens for the taking. I stopped to listen and it’s quiet, only the sound of people laughing in the distance, birds talking among themselves in the branches overhead and a town clock striking the hour.

Whitefield, to me, was one of those places people in the megalopolis dream about retiring to after socking away the fruits of a lifetime. Statistics I found among the public records were interesting as well. In all of 1975, the three-man Whitefield Police Department investigated only 93 criminal offenses, including five burglaries and three for drinking in public. Those compared to three burglaries and no drinking in public arrests in 1974.

Twenty-four people died in Whitefield during 1975, all but one from natural causes. Warren Bean, then 28, shot himself in the head on September 7th. The next youngest who died was Alda Young, 66, of a heart attack.

There were 246 people over 65 living there in 1972 along with 1061 between 18 and 64; 408 were school aged. The most discouraging aspect to making a home in the town was its per capita income in 1972 of $2,784. As with small towns everywhere, most of its sons and daughters left after graduation to seek a decent living.

Mrs. Claudia Sullivan, assistant to Selectment Bill Robinson, a car salesman, Wendell Rexsford, an excavating contractor, and Paul La Duke, an accountant, told me that population in Whitefield has been picking up in recent years. She named off several young families who had recently moved to town, saying she believed it was because they were tired of the fighting the megalopolis. One name she mentioned was Stan Holz, the local gunsmith who had made the move three years before. When I entered the shop, he was reading a book.

Stan was a tall whip of a man, about 30, who told me he left New York City and a good paying job with New York Telephone because he was slowly going insane. “When I began yelling at people who weren’t pulling away from stop signs fast enough, I knew I was going down,” he said.

“I saw other, older executives in the company drinking heavily, some were alcoholics. It was a place where any type ingenuity was frowned upon. You did things the company way, operating on the principal of ‘cya’…you know what that means? It means cover your ass, always have someone else you can blame for a foul up.”

Stan said he could see a predictable cycle facing him. “You start with the company as a young man and they pay you well with good benefits and you learn how to spend a lot of money. Pretty soon you’re spending more than you’re making, then you’re hooked into the firm for life, scared to death that you’re going to lose what you’ve got and drinking to forget how much you hate what you do. It wasn’t for me, or for my wife.”

Sandy Holz is now the part-time city librarian, but she’s still on a maternity leave of absence since the birth of their daughter two weeks ago.

“That’s another thing,” he continued, “We wanted to have a child but not if we had to raise her in the city.”

Stan had always had a hobby of gun collecting, so when they decided to leave New York, they took $12,000 in savings and moved to Whitefield, a town they had visited while vacationing in the White Mountains one summer.

“It was natural that I open the gun shop. The big salary was gone and we were looking for happiness and a slower pace,” he said. “There are quite a few young, well-educated couples who have done the same thing we have here. They came to escape all those people and the city. Some of them are working in one of the two small factories. Others are managing any way they can. The ones who have a natural talent of some kind, like art or writing, have an easier time of it.”

In less than a minute, Stan rattled off several names of local merchants who weren’t native to Whitefield. “You’ll find many older people came here years ago for the very same reasons. This isn’t a typical clannish small town, neither is it afflicted with the ‘ye olde’ syndrome that usually strikes most of the older New England villages. It’s basically a friendly, clean, quiet place to raise a family and find some satisfactions other than monetary.”

When I finally did turn the key on the coach that evening, I had learned more about a small Eastern village than I knew about my own home town, but there was no regret in the time spent. There was also a fresh perspective on those license plates.

Received in New York on June 28, 1976

©1976 Mike Masterson

Mike Masterson is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Sentinel Record (Hot Springs, Arkansas). Mr. Masterson will travel throughout the U.S. with his family and write about the country and its people in 1976. This article may be published with credit to The Sentinel Record and to Mr. Masterson as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.