Sioux City, Iowa — Kathy and I sat staring blankly down the gleaming corridor. Mingled aromas of antiseptic, disinfectant and the smell of just plain hospital engulfed our nostrils. Everywhere were men and women in white garb shuffling to and from rooms.

The activity and mostly-solemn expressions were some assurance if only imaginary, that Brandon, our rambunctious five-year-old was in good hands.

An hour earlier while in hot pursuit of a wayward rubber ball, he hadn’t seen a thin wire stretched across the concrete in front of him. The metal ribbon had caught him at eye level and flipped him on the back of his head.

So here we sat outside of the X-ray ward in St. Luke’s Lutheran Medical Center, awaiting the verdict.

To pass the time, we talked about our journey northward from Harrison, Ark., my hometown. In ten days we had sprinted through western Missouri, clipped the northeast corner of Kansas and seen the southwestern-most wedge of Nebraska.

There had been many now faces and friends in that time.

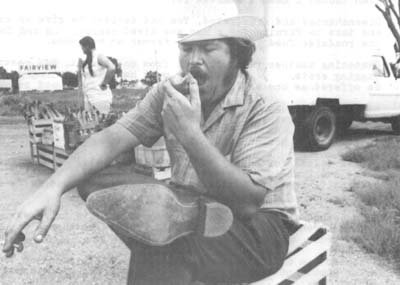

Two of those had been Tom and Cathy Sammons, who were sitting in front of the roadside produce stand along Hwy. 75 in Nebraska when we stopped to talk for a while.

A grit-laden wind born on the Nebraska plains whipped at the young couple’s impromptu market discouraging many motorists from stopping. Undaunted, Tom sat on an empty wooden fruit crate munching a ripe peach while Cathy stood behind a row of boxes, staring across the flat, monotonous landscape.

They both had received me warmly and seemed eager to talk about themselves. Brandon had been sleeping that afternoon and Kathy stayed inside the Lady K to catch up on her diary.

Tom, it seems, was a high school dropout who only recently had turned 24, while Cathy had gone on to finish school, become a waitress, marry Tom and bear two daughters in her 21 years.

I asked how they met. Cathy smiled and said, “Well, I was a waitress and he was working for a man in Kansas. He kept coming in the cafe and first thing you know one thing led to another. Heck, that’s been nearly four years ago now.”

Tom said he was kicked out of high school when he got into a fight with a fellow he described as a rich kid. “The principal felt moved to expel one of us,” Tom said, “and you might have known it wouldn’t be the rich one even though I hadn’t started it.”

Disenchanted and frustrated, Tom had decided to give up school altogether and take to farming for a man who lived nearby. He and Cathy were peddling the roadside food for that same farmer on weekends.

Snatching another reddish peach from one basket, Tom reseated himself on the sagging crate. I suppose I must have looked hungry, for after a moment he offered me one and I accepted. It was a darn good peach, too.

He went on to say how he and Cathy had spent summer weekends beside Hwy. 75 for the past two years. Their two young daughters stayed at home 22 miles away with a sitter. On a good day the Sammons could earn $25 or $30 at their stand. I didn’t know how, though, since a giant bag of tomatoes had cost us only $1.

We had talked for nearly 30 minutes and could have killed the better part of an hour, but Brandon was awake from his nap and raring to go. Before leaving, I recall having asked Tom what he hoped to be doing ten years from then.

He stood there for a moment then tilted his large straw western hat back on his forehead and sighed, “Well, I hope by then I can have my own farm and a new truck. We -really don’t want a whole lot, just something of our own.”

I sensed Tom and Cathy were at least a little saddened to see the Lady K swing about and chug away. Only one other car had stopped to make a purchase during the time I had spent there.

An elderly nurse interrupted our reminiscences saying they had completed one set of X-rays on Brandon’s head and were going back for seconds. Kathy flashed me her “uh oh, something’s wrong” look and gripped my hand. Thanking the nurses I quickly changed the subject and returned to recollections of our trip to stay occupied.

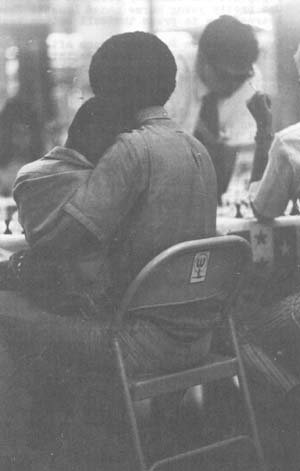

We recalled meeting a man named Bill Martz, a shy, dark-haired lawyer of 34, who had been busily taking on 50 chess players a week earlier in a Topeka, Kansas, shopping mall.

He had talked with me while I followed him around the giant table. The native of Minnesota spent less than five seconds studying each move before stepping forward to the next opponent. He had told me he was an International Chess Master, which meant he had played and won games in other countries.

Kathy chuckled as she recalled his tendency to blush when embarrassed, which

was often. One of those times was when I asked if he had ever played a chess match against Bobby Fisher. “Yeah,” he had said, casting a glance toward the floor, “We played an exhibition match once…played to a draw.”

The challengers had fallen by the wayside until Bill called it quits about 5:00 p.m. At the end of the day he had Played 52 games and won all but two. There had also been four draws, one by a 14-year-old whiz kid named Billy.

The bespectacled man had sighed and loosened his tie when it ended. “I’ve been doing this in a lot of states,” he said.

A non-practicing attorney, Bill had also said he drove his car to wherever these marathon, come-one, come-all matches were being held. Although tired, he looked as though he could have taken on another 50 opponents right then.

It had been interesting to follow Bill around the table and watch everyone matching wits with this man who would rather play chess than plea bargain.

I had seen the games as much more than an enjoyable way to kill an afternoon. To me, they represented a very real part of America, that being the urge to compete, to challenge your neighbor and win at all costs, to show you are better than the next person, to distinguish yourself from the mass.

At the table had been elderly, young, male, female, wealthy, poor, black, white and brown. Each wasn’t interested in the book on chess offered as a prize to the victorious. Instead, they had individual points to prove…to go home a winner and rejoice ever their wit in bed that night.

A metallic table bearing our sleeping son was wheeled from an open door. The nurse motioned for us to accompany her back to a cubicle in the emergency room. Rousing once, Brandon fought to stay awake but lost the battle despite our encouragement. We stood over him until a middle-aged physician entered the room and read the technician’s report. “I’m afraid he has a three-inch skull fracture in the back of his head. We’re going to have to watch him for a few days…that means have him admitted.” I tried to cheer Kathy by telling her it was all a bad dream, that no one ever has skull fractures in Sioux City, Iowa, especially a five-year-old Arkansan. But neither or us could laugh.

In the days that followed, we met remarkable pediatric nurses who continually displayed remarkable capacities for patience usually reserved for bishops, judges and experienced math teachers.

After his first night, Brandon initiated a steady barrage of requests for popsicles and immunity from the bedpan since noisy flushing is far more exciting. One pretty young nurse named Lynette Thompson soon caught his eye and he learned how to press the call button beside the bed to capture her attention.

Lynette sat in Brandon’s room after he had fallen asleep one evening and told us how she had been a Registered Nurse for slightly more than a year at St. Luke’s. She was originally from a small town in South Dakota named Esmond, but the community of nine lost their zip code and post office in 1973 and is no longer an officially-recognized bustling metropolis.

“It has a population of two now,” she said. “There’s a Methodist church and a town hall building. I don’t get back as often as I should, since my parents still live there.”

The 22-year-old, pixie-faced woman told how she had grown up on a 450-acre farm near Esmond where her father raised wheat and oats. She became a nurse because she wanted to meet people and get away from the rural life. Ironically, Lynette now wanted to get experience in every phase of nursing by someday moving to a smaller hospital.

Her carefree expression changed suddenly as she swerved the subject to her feelings for a baby being kept in the pediatrics ward. The infant was in a bed beside the nurses’ station, but didn’t know where it was and probably never would.

Lynette said the baby showed no brain waves or any reaction to our world. The only movements from him were leg twitches diagnosed as minor seizures by resident physicians. She said there was no hope for the baby to ever be anything but a breathing organism in a bed somewhere…oblivious to existence as we know it.

He had been at St. Luke’s several weeks for testing and was scheduled to be taken to a hospital in Omaha, Nebraska, the next morning. Lynette, although single, said she felt something almost maternal for him which she admitted was unusual for her as a professional.

“He doesn’t even have a sucking reaction to allow him to eat,” she said. “I have to force feed him. Yet, without even a single response, there is some unexplained communication between us, I’ll be sorry to see him go.”

Later that evening, I looked both ways then tip-toed down the hall and through an open door to the baby’s bedside. He was as she had said…a tiny infant unmoving yet breathing, staring straight ahead. There was only the occasional twitch of that twig-like leg.

The little follow never knew I stood there 15 minutes pondering over him.

When I finally left the room that night, I went back to Brandon’s bed and gave him a hug. He hugged me back.

Kathy and I spent part of the next day comparing Sioux City to other towns we had seen along the highway. The land around the city was rolling and rather barren, but there was a ruggedly attractive quality to it.

Some towns in the United States had erected plaques and signs in observance of the Bicentennial Year. There had even been a few with banners stretched across the main streets. Not Sioux City, oh no, their ingenious street department had decided to paint the principal thoroughfare with red, white and blue stripes as the center lane divider.

Those colors contrasted sharply with the dull red-brick buildings that lined the street. It was apparent from their modest height that banks in Sioux City had not yet entered into the “build the tallest building” competition.

Like in so many other communities here, too, was a downtown portion remodeled to combat the relatively new shopping center on the edge of town. A bank teller named Reah said the word comfortable could best describe Sioux City.

I agreed, it was a comfortable town. If you listened closely, you could hear the serene bawling of cattle from the nearby stockyards. It took absolutely no effort to detect the livestock…nasally.

At night, the town became like a small city from out of the early 1960’s. Teenagers and older sporting duck tails and driving old cars lowered in the front came out from seemingly every side street. They unrolled cigarette packs from tee-shirt sleeves and some sat hunched over on their motorcycles. I felt as though I’d been fitted into a time machine and sent back to this community of 90,000 in the year of Buddy Holly and the Big Bopper.

Three days passed quickly and before we settled into a routine of life at the institution, Brandon was shedding the colorful hospital pajamas and stepping back into his navy blue shorts and burgundy tennis shoos.

It was a good feeling for all three of us to step through these glass doors into a warm mid-western sun. Perhaps it was an instinctive reaction, or because we all felt the same way at the same moment, but we put our arms around each others’ backs and walked that way to the car.

In less than an hour the Lady K was disconnected, gassed, oiled, watered and rolling northward toward the Dakotas.

CACTUS FLAT, South, Dakota — Some people call it dusk, others say twilight, but whatever the eerie gray light before sunrise is, it crept through, the burlap curtains of the Lady K and roused me at 5:30 one morning.

I lay there for a while reflecting on the fantasy-like Badlands only four miles to the north and how they seemed to spring from the lonesome, rolling landscape of South Dakota like foreboding dirt-clod skyscrapers.

The day before, we had been looking at seemingly endless miles of parched corn and hay, then the towering dirt columns unexpectedly appeared over a rise and spread for miles in the distance.

It was one of those times I just couldn’t roll over and go back to sleep, so relieving the urge to be mean I rolled over and yanked Kathy’s big toe. She mumbled and rustled the sheets.

I had it in my mind to walk to the crest of a nearby hill and watch the sun spread its first rays across the furrows and crests of those peaks.

Once awake, she agreed to the plan with a massive yawn and we teamed to coax Brandon from beneath his covers. It only took a few minutes to brew a thermos of coffee, boil several eggs and toss the works into a paper bag.

When we stopped into a cool morning breeze, the horizon in front of the Lady K was glowing like the red-orange embers of a late evening campfire.

Scurrying like lemmings to the top of a cliff about half a mile away, we plopped the blanket and ourselves down only minutes before the sun bid us good morning.

It was still, very still. A few fellow campers were stirring in the distance, but they were no distractions for the most spectacular, no-admission performance anywhere.

The top of a distant butte was literally on fire for an instant and just as suddenly, we were bathed in a blinding glare.

It was then we heard the Badlands’ children greeting their mother sun. Coyotes bayed for nearly a full minute. A woodpecker began banging his head furiously against a cedar tree across the river below. Doves cooed, songbirds chirped. The world had made it to another day.

It was Brandon’s first sunrise. He sat in silence on the far edge of the blanket. This was his way of saying he wanted to think about it alone. When he finally did speak, it was to ask for a hard-boiled egg. Kathy said she was saving them to throw to the howling coyotes if they decided to invite us for their breakfast.

“Well, we could always run for it after throwing them at the wolves…”

We ate all but one of the eggs and drank the coffee and talked about how we should do this sort of thing more often, then hiked back down the hill.

Wounded Knee, South Dakota — Site of the 1890 massacre of hundreds of Sioux Indian men, women and children. In 1973, this small village on the rambling Pine Ridge reservation was the scene of a violent and lengthy siege by young Indians.

We decided to fill a gallon jug with ice water and see what’s happening there today. The community was 90 minutes from our campsite through the reservation.

Brandon insisted we take along the uneaten boiled breakfast egg to have with the water. Kathy said it sounded more like a prison diet than lunch.

We passed many small shanty-like houses. Most had rusted car bodies stacked in yards and fields beside the homes. It was a lonely, desolate drive. The only greeters were occasional shirts and denims that waved at us from clothes-lines.

Over one rise was a young boy with cave-black hair clad in a red cloth and naked above the waist. He was chasing a pony across a field.

Onward, past the tiny Indian hamlets of Sharps Corner, Kyle and Porcupine, we drove. Then, as if appearing from nowhere, there was a pick-up truck behind us and a car in front. We proceeded in this fashion for several miles. I became somewhat uneasy. Words of warning issued by an Episcopal priest in Sioux City, Iowa, rang in my ears. “They’re still having some trouble on the Pine Ridge reservation. If I were you, I’d pass it up this time…”

But my wildest anxieties melted as the car in front pulled off and the truck passed in a cloud of gunmetal-colored smoke that burned my nostrils and made my eyes water. Then we were alone again for the remaining 12 miles.

The story of Wounded Knee is much larger and far more flamboyant than the place. I suppose I was surprised not to find several tourist trading posts, each boasting a peek at the “world’s largest prairie dog,” or a hot dog stand and a snow cone concession.

But there is only a wind that continually whips through the shallow valley and two dirt roads winding around to residences and a few buildings.

A majority of those 20 or so homes are the federally-funded, cracker-box variety, but a far cry better than what we saw many Indians living in along the road.

On the right of the highway as you drive southward into the near-treeless valley, is a small knoll and an overgrown cemetery. A church once stood beside the graveyard, but it was burned after the siege of 1973.

We spent a few minutes walking among the cemetery markers. One unnamed wooden cross lay uprooted on top of a few scattered plastic flowers. There were Indian names on several markers…Little Moon, John Afraid of the Hawk, Jr., Two-Two…and others.

The most extravagant was the grave of Lawrence Buddy LaMonte. It was a flat six by three-foot marble stone lying flat on the ground with his photo inset. The inscription reads, “Two thousand and five hundred came here in 1973 and only one remains.” There was also a picture inscribed in the marble of a Chief telling his son good-bye, but that they would meet again in heaven.

LaMonte’s name didn’t register but I assumed he was one who died in the 1973 violence.

There was also a large white monument bearing the names of Indians killed at Wounded Knee, many of whom were buried in a mass grave.

I felt sadness at realizing that here, amid the woods beneath our feet, were empty, decayed bodies that once carried human spirits and now they were gone and largely forgotten.

Kathy said she felt an indefinable sense of awe at being there. It wasn’t the physical part of Wounded Knee. As I said, there is nothing there except for a few houses.

Rather, it’s the feeling some experience when they’re in a place that has held so much history, a spot that has seen so many come and go…It’s a reverence, a respect for what has happened there.

From the cemetery, we drove to the bottom of the knoll, where a tourist store, a red-log museum and a post office once stood. They were destroyed in 1973. The roof of the store has fallen. Remains are surrounded by empty beer cans and black-eyed susans. The adjacent museum building is without windows or doors. A swarm of bees had taken up residency and, from the sound of their warnings, didn’t care for our intrusion.

Across the drive from those buildings was a smaller log house. It, too, had partially collapsed and was without windows or doors.

Wading the weeds, we went inside. The walls were scrawled with graffiti about the American Indian Movement “AIM,” and how “cool” it is. I also noticed Russell Means’ name, leader of AIM, carved there with a knife.

But it was Brandon who made the most interesting discovery when he asked what the writing on the wall of a back room spelled. It appeared to once have been a bedroom. Part of the wall had been torn out, but on the remaining section were written detailed instructions for the treatment of puncture wounds and resultant infections.

The steps for first-aid were numbered. Someone had apparently used the small building across from the store for a hurried, on-the-wall course in caring for bullet or stab wounds.

Two churches remain standing near Wounded Knee, but the windows on one were boarded and the other looked closed, so we didn’t stop.

Except for the new Post Office, which is located in a small trailer beside the housing project, and a state historical marker that is the extent of what we could find at Wounded Knee.

The marker, located at the bottom of the hill, had been vandalized to read…The “Massacre” of Wounded Knee rather than the originally inscribed…The Battle of Wounded Knee.

Inside, I had to agree with the vandal’s philosophy. I could find no justification in my understanding for the U.S. Seventh Cavalry slaughtering hundreds of Indian women and children the way they did shortly after Christmas in 1890.

After more than an hour we left Wounded Knee, but didn’t drive a half-mile before encountering a portly Indian woman standing beside a well-used blue Ford with the hood up.

Pulling alongside, the following conversation between us took place:

“Hello, in there something I can do to help you?”

“No.”

“What’s wrong with your car?”

“Outta gas.”

“I see, well can I give you a lift to the nearest station?”

“No.”

“Isn’t there any gas around Wounded Knee?”

“No, Porcupine.”

“What if I stop at Porcupine and ask someone to drive back and bring you some gas?”

“Okay.”

“By the way, are you thirsty? We have some water if you’d like some.”

“Yes.”

Out of the car, the Masterson herd, intent on assisting the stranded woman whether she wanted it or not, stampeded to her car.

A small boy she called Urva, who was clad only in a disposable diaper, was continually running in circles around his mother’s car. His bare feet clapped against the hot pavement and he would hide his face from us when we called to him. Another youngster was asleep in the back seat.

Her name, she told me, was Adeline Quick Bear and she had lived in Wounded Knee for most of her life. Although she seldom said anything besides yes or no, I did manage to find out she had been standing in the heat beside the road for three hours.

She drank a cup of water and gave another to Urva, who was a handsome boy. I couldn’t help noticing his frail back was covered with angry red whelps from insect bites. They didn’t seem to bother him.

Before putting the jug back in the car, another auto containing a burly Indian man and two teen-aged boys with B-B guns pulled up beside her and he said he could siphon some gasoline from his tank to her’s. All he needed was a large container, which they didn’t have.

As it so happened, I’d recently bought a half-gallon of windshield cleaning fluid on sale that I agreed to dump beside the road and donate to the cause. There was never a smile, or even acknowledgement that my $1.89 super bug removing cleaner was soaking into the soil.

A few sucks, grunts and spits later the older Indian fellow had a half gallon of gas in her car and it was running…barely.

And there on the plains of South Dakota, Kathy, Brandon and Mike stood in the noonday sun as she tromped the accelerator to the floor and left us standing together without so much as a thanks, goodbye or even the hint of a smile. As a matter of fact, she hadn’t smiled through the entire roadside ordeal.

Besides that, thankless Adeline Quick Bear had taken our plastic jug as a remembrance.

Kathy shrugged and suggested we count the jug as her Christmas present this year, “Just one less we’ll have to buy.”

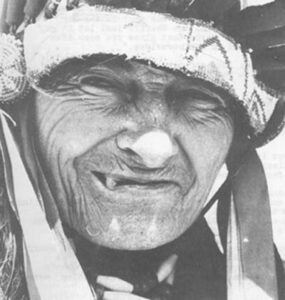

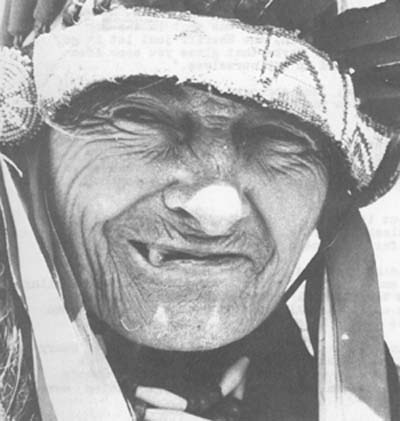

Later in the day, we drove to Interior, South Dakota, headquarters for the Badlands National Monument. There, in the middle of the street, I met a salty character named Herman Bordeaux, who claimed to be half Indian and half Mexican, but I suspected more of the former.

Herman, it seems, had just exited from a local bar and was winding his way down the village’s one dusty street when he happened across us.

I discovered he apparently had once owned a Buick LeSabre but he claimed “two young girls he picked up took it from him on the Rosebud reservation and left him stranded.”

“Say, I sure could use a dollar,” he said, flashing a silly grin. “Well, Herman, I can give you a quarter I suppose.” “Oh, that’ll do. Just want to get me something to eat, you understand.”

He was a congenial fellow who asked me to take his picture before we parted. When I climbed out of the car, he immediately shoved his cowboy hat down and broke into a wide grin that revealed four missing front teeth. “I’m 56,” he said. “Wouldn’t believe it would ya?”

I had to admit, Herman looked younger than his years. He went on to tell me how he had lived in Rapid City, S.D., for quite some time and how he spent part of his military career in Arkansas.

I developed a liking for Herman, but not enough to give him a dollar when he asked for it the third time. He understood and smiled another one of those friendly toothless smiles before turning to continue his aimless journey down the street that led only to a highway.

I sincerely wished him luck, but he never knew.

GILLETTE, Wyo. — We had counted on spending a night out of the Lady K in this small mining town along the northeastern section of the cowboy state. But that was before we discovered a room for the three of us would be $29-$30 plus tax.

Donna Wright, who was helping operate the family’s Farmer Co-op Self Service Station, said the city of 7,100 has literally become a boomtown for coal mining and even gas reserves beneath the windswept prairie.

“I’d be surprised if you could even find a room in this town,” she said, “You know it’s a long way between towns out here and the miners have taken about everything.”

As time passed that afternoon, I discovered Donna had been right. The only other room we could locate went for the same price as the first but without an air conditioner or television set. I’d always wondered what life was like in a western boomtown and 30 minutes was enough to snuff that curiosity. We hadn’t encountered such obvious dollar-grubbing since departing the eastern megalopolis.

Donna had also told me as I stood laboring at her pumps to save three cents a gallon, that a recent survey showed Gillette to have the highest cost of living in Wyoming. “That same motel you stopped at first charged $21 a night for a double room last year,” she said. “I don’t know where it’ll stop.”

We had one thing in common. I didn’t know where we were stopping either.

Back on Highway 90, I piloted the Lady K farther northward to Sheridan, Wyoming, a yet-to-boom town of about 11,000 where motel rooms with two beds can still be had for less than $20.

By the time we called it quits for the day, Brandon was cranky and complaining he didn’t want to see any more of America, but his edge was dulled, by a good meal and a hot bath.

Behind us lay a trail of thousands of miles and hundreds of newfound faces and friends. We had just turned more than 100 days on the road and still hadn’t really adjusted to a lifestyle of gypsies.

The Big Horn Mountains of northern Wyoming leap to hover in the distance as a backdrop to the city of Sheridan. They are rugged…beautiful in the way a cactus is beautiful…a product of geography reinforcing the image of what the state of Wyoming is supposed to look like in the back of all our minds.

Along the highways we had seen many farmers gathering their bales of hay and food for the winter months. Already, even though the Bicentennial summer has several breaths to draw, it is cool here, a chil1 that ordinarily comes in late October to the South.

Crow Agency, Montana — The next day, barely two miles from where General George Armstrong Custer fired his final shot at a red American on a ridge near the Little Big Horn River, we navigated the coach between more than 400 white teepees being occupied by thousands of Indians from more than eight nations.

The event was known as the annual Crow Fair, held on about 50 acres inside the Crow reservation. But the Crows only hosted the massive gathering that lasted for three days. All around us were men, women, children and their animals wandering the dusty grounds.

The terrain was flat with a few tress for shade, but for the most part, teepees were standing in spaces reached by the sun from dawn until dark. A southerly wind whipped the loose, dry soil into the air and our eyes as we walked around the circular arena which had been erected for ritual dances in the evening that the Indians called pow-wows.

Brandon was thirsty for a grape soda. Nothing else would do so we went from one hastily-constructed wooden concession stand to another until we discovered one specializing in grape.

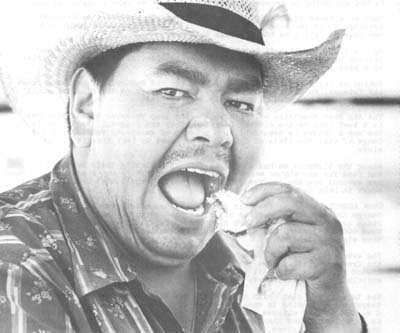

I plopped down beside a giant of a dark-skinned man who was busily devouring a cheeseburger, rinsed with a cup of coffee. After the final bite, he smiled at Brandon, then at me and Kathy, “Oughta try one, man. Those are the best burgers I’ve ever had, bar none,” he said, wiping his mouth with a paper napkin.

“As a matter of fact, it was so darned good, I’m gonna have another one, by golly.” He waved his hand in the air and a younger Indian man took the order. I discovered after a few minutes that his name was Roy Coyote from Alberta, Canada, a Blackfoot Indian who made the trip just for the Fair.

He said he farms in Alberta and travels to Indian gatherings whenever he can. “These things mean a lot to me. They mean a lot to many Indians.”

I learned there are Indians who consider events like the Crow Fair to be a religious observance. “Just listen,” Roy said, “you can hear an old man chanting to his god right now in one of the teepees.” I cocked an ear. He was right, there was the wailing of a man coming from one of the tents. “Tonight there will be many chanting. The gathering of so many Indians is a sacred happening in the eyes of the older ones.”

Roy said he once weighed 486 pounds, but has slimmed considerably to a trim 298 during the past two years. His secret, he said, was in only eating whatever he wanted one time a day. Today’s meal was two whopping cheeseburgers and three cups of coffee. “Man, I feel light as a feather,” he said, after chomping into the final bite.

When others sit down to routine daily meals, he takes a long walk and drinks another cup of black coffee.

Interested in Indian attitudes today, I asked Roy about these and other issues and problems facing the various tribes. He tilted a white straw western hat back on his forehead and sighed. “Well, since I live in Alberta, it’s hard for me to keep a finger on what’s happening in the states all the time.”

The younger Indian who had served Roy his cheeseburger, interjected by saying he felt there has been noticeable improvement in the living conditions and benefits for Indians since the Wounded Knee violence in 1973.

His name was Dean Fallsdown, a 23-year-old Crow Indian who was working for the U. S. Forest Service in Crow Agency. I asked if he had been involved in the Wounded Knee bid for recognition. He said no, but added that he had been a part of a riot in Albuquerque, N.M., during 1973, when a large group of Indians threw the mayor of that city out of his first floor window.

“I’ll say that the American Indian Movement and Russell Means did help the Sioux to get more attention and assistance from the government and others,” he said.

“Let me just give you an idea of what it’s like being an Indian,” he continued. “Not long ago an Indian girl who was over six feet tall was hit by a car on the highway and the driver left. Now it just so happened that blood and hair were found on this white guy’s car down in Wyoming a short time later. The man said he thought he hit a dog in the road.”

“He was the one who did it. There was really no doubt, but the Sheriff wouldn’t even try to get the man brought back to answer the charges. It was just shoved beneath the rug. You know, the ‘oh well, it was only an Indian’ attitude.”

“And there was another incident where my cousin was shot in the leg by another man of the majority race. Again, the Sheriff just let it go. I don’t think it was even investigated. Maybe that gives you some idea of why Indian movements began to stand up for ourselves.”

Roy, who was still seated beside me, just shrugged and stared into his coffee cup. I felt he wasn’t sold on the AIM philosophy, but he never said if he was or wasn’t.

Dean went on to talk for a while about the local Crow tribe and how now marriage partners and their offspring must now be officially enrolled by the tribe to be able to come on the reservation. The reason was to make at least some attempt to keep the Crow blood lines from becoming mongrelized with other races.

I also learned there are about 150 young Indians in their 20’s and 30’s who have started voting in blocks at tribal functions in order to change issues within the tribe. So far, Dean said, they have been very successful.

As we talked, numbers of Indian boys and girls galloped past on their ponies, followed closely by small packs of barking dogs. They were squealing with delight and slapping at their animal’s backsides with switches. Brandon’s eyes followed them until they disappeared behind a row of tents. Then he smiled and told me he wanted a pony.

Dean had formerly been a deputy on the tribal police force but grew weary of driving the miles of dirt road along the reservation boundaries. He said his job with the Forest Service pays better and gives him a chance to work outside. He was born in the middle of ten children, including seven brothers and two sisters.

Having seen the small houses occupied by Indians throughout the West, I was curious about poverty within the Crow tribe.

“What do you mean by that?” Dean fired the question before I had hardly let fly with mine. His eyes reflected a measure of hostility and he had raised up in his chair from a slump.

Before I could explain there was no affront intended in the question, Roy chuckled and stepped in to spread a cooling salve on the apparent sting. “Oh now there’s poverty among almost all Indians,” he said. “I can understand your being curious about it, though. There has been a lot said and written about that very thing.”

Dean quickly dropped his defensive position and went on to explain how there were a number of Indian families who were living poorly on the Crow reservation. He also told of a corporation that was mining on part of the reservation at that very moment and that was supposed to be negotiating a deal whereby every Crow Indian who lives at Crow Agency will receive $400 or $500 a month for about 20 years as a result of their digging.

Nearly two hours had passed since we sat down at the Fallsdown booth, but they had been hours well spent. Roy Coyote and Dean Fallsdown had shared a great deal with me and the only lingering problem was the inevitable explanation to my son about why we couldn’t find room in the Lady K for even a “very, very, very small pony.”

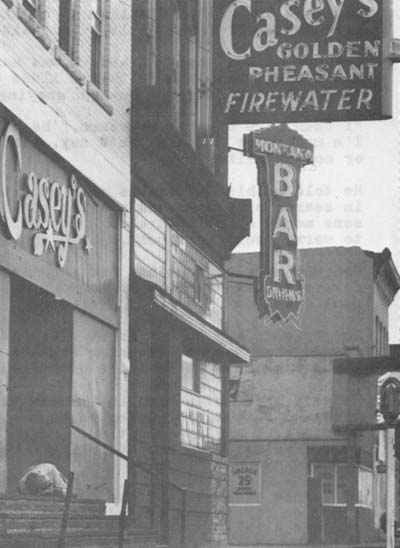

Billings, Montana — Just the name conjures visions of tall mountains, blue sky, clean water and wide streets where there is opportunity to draw a pine-scented breath.

Perhaps that’s why I was surprised to discover the foul-smelling oil refineries, an unswept downtown area and dozens of pitiful alcoholics wandering around railroad tracks near the business section.

Some of those fellows had even lapsed into stupors beside the rails and in front of bars.

They lay there in full view of everyone, including policemen.

The Yellowstone River flowed beside the town, a wide, free-flowing stream on whose banks we parked the Lady K for three days. However, the water we saw in the Yellowstone River at Billings wasn’t clear and pure, it was dingy. In pools beside the primary stream were rocks and cans covered in dingy green algae.

Now I’m by no means a critic of Billings, Montana, or any other city in America we pass through on our journeys but I can write about what we see, hear, and smell. Unfortunately, there isn’t enough time or space to delve deeply into the causes behind issues and happenings in each town. I wish there were.

I am certain there are many good things about Billings and their Chamber of Commerce could, no doubt, provide anyone interested with more information than they need. For instance, we discovered another one of those enclosed shopping malls on the outskirts of town that any community would be proud to claim and Brandon took us to a Walt Disney double feature at the Fox Theatre that we thoroughly enjoyed.

But still, there were those men wandering aimlessly along the streets and the stench from the refineries to greet us when we left the softly-padded movie seats.

I sat beside one of those men along the tracks and we talked for a while about his life. Ron Davis had been sleeping on a loading dock next to a railroad track when I walked up on him. He smiled when he sat up. “Must have dozed off for a while,” he said in an almost apologetic tone.

I asked if the wooden platform was hard. He said he’d become used to it. Ron’s eyes were laced with red lines and he continually shook his head while running fingers through graying hair.

“I been here nearly two years,” he said, “holding down odd jobs and such. I’m a drifter I guess you’d say, that is, I don’t have no permanent roots or nothing like that.”

He told me his day begins when he gets up and starts wandering the street in search of a meal and a drink. “If I’m not working, I can usually borrow some money or collect enough pop bottles to get by. Heck, I don’t have to worry about room rent, just getting by.”

Ron was married once and had a child who died. The marriage broke up a few years later and he began roaming. “I have me some friends here,” he continued.

The friends Ron talked about frequently gather at a nearby hole in the ground when the sub-freezing Montana winter sets in. “We get in there and live,” he said. “We build us a fire and all and, well, we get by okay.”

He said he’d never been in trouble with the police, but there have been times he’s thought of doing whatever it took to get enough for a meal and a bottle…mostly a bottle. “Haven’t been pushed that far yet,” he said. “Oh, I’ve tried to stop drinking several times, but I guess I just really don’t want to.”

We leaned back against the dock together and stared across the tracks. A police car passed by and the young officer gave me the once over, ignoring Ron altogether.

“They go by every now and then, but they don’t bother me none,” he mumbled.

I couldn’t help but wonder what life meant for him…was there any purpose to living? “That’s a good question,” he said, dropping his gaze to the ground.

We sat in silence for a full minute.

“I suppose not really, I’m just sorta here. I can’t do nothing that nobody else can’t do better, ‘cept maybe eat and drink. I suppose I’m just existin’ until I die one day…of course, no one’s gonna care then, either.”

“But I can’t and don’t blame no one for that ‘cept me, you understand. A man’s responsible for himself and if he don’t turn out no better than me, well, then he don’t deserve no better.”

I began to think about my fundamental relationship to Ron. Here we were not an arms length apart, two human beings breathing, talking, belching, blinking…two arms, legs, eyes, hands, feet each. Yet one is largely scorned by society, living in admitted hopelessness while the other had an accepted place in that society and much to live for.

The difference, I reasoned silently, has to be deep inside the intangible but vital human spirit. Once it’s broken, resignation and surrender soon follow. I have seen literally thousands of men and women whose spirit has been shattered for one reason or another, and I have seen the scorn fellow humans heap upon them for their weakness.

I’ve also talked with many Ron Davises and have come to the conclusion very few regain that spark of self-respect once it’s doused.

That lost spirit was the only gut-level difference between Ron and myself. I hoped there wasn’t an unknown thief waiting to one day steal mine away and leave me as empty as this man.

In the distance a freight train blasted its forlorn warning to oncoming motorists. Ron yanked a cigar butt from his shirt pocket and wedged it firmly between rotting, yellowed tooth. The last paper match from a book that advertised a Billings’ bar brought the foul-smelling stem to life.

His eyes shut, obviously treasuring the moment. “Say,” he said in a quiet voice, “can you spare 75 cents or so?” He didn’t look me in the eyes when he asked. I reached for my wallet and yanked out a wrinkled dollar bill.

Handing it to him, I swore I could see the image of a wine bottle in his pupils. I knew why he wanted the money and I knew the stuff was probably going to kill him one day, but then for Ron Davis…I also knew there was nothing else that mattered and nothing else I could do to make him feel a little better for the moment.

I stood to leave. He struggled to his feet, stumbling to gain his balance. “Gosh thanks, man…you’re a good guy.”

I smiled and, for lack of anything better to do, grabbed his bony shoulder and patted it twice. The last I saw of Ron, he was going into a seedy-looking place with three flashing beer signs in the window. He was smiling.

The next day Brandon, Kathy and I took in the Yellowstone Exhibition in Billings, a giant annual fair that attracts thousands from throughout western Montana.

After observing a large number of Montanians wandering the grounds, I came to the conclusion that almost every man in the state classifies himself a cowboy. I felt almost naked without a white straw Stetson and a pair of amply-heeled leather boots. Kathy’s closely-cropped hair also stood out amid a female sea of puffy bouffants.

There was no doubt, we were city dudes in Marlboro Country.

I remembered one follow along the highway into Billings at a store called The Fort, who rose from behind his store counter with a cannon-sized revolver strapped to his waist.

I’d gone in to buy Brandon a grape popsicle and ended up watching the self-styled Matt Dillon stalk a hummingbird-sized moth around the interior of his grocery.

He had seemed far more interested in nailing the bug than in taking my dime. I thought for a while he would surely remove the hip cannon and begin blasting at the fluttering insect.

Finally, his blonde wife came from a back room and accepted my coin. Her husband by then had cornered the moth between a row of chili can carne and a stack of Nabisco cookies.

I asked why he was wearing such a large gun on his alligator-skinned belt. She had smiled and said, “Just in case.”

When I left, he was holding the bug aloft in triumph and grinning like held just beaten Wyatt Earp to the draw.

“Oughta have him mounted,” I offered going out the door. He stared pensively through the screen.

The faint outline of mountains to the west of Billings were beckoning. A witty man named Ziggy, who owned the KOA Campground where we had hooked up, filled our propane tank and asked if he could ride along on the underside

I told him sure if he didn’t mind tending to routine dumping of the Lady K’s sewer tanks. He stayed in Billings. Our portable home moved farther west.

Tacoma, Wash. — After driving the breadth of this nation, from one ocean to the other, I sat at the table inside the Lady K to try to tell you the significance of what we’ve seen along the way.

But the blank sheet of white paper has suddenly become difficult to cope with. We have seen so much during the past five months and 10,000 miles…who can evaluate and compare the various Americas with any degree of accuracy?

Oh, there have been the more obvious evolutions within communities in East and West, including the growing numbers of downtown shopping malls that I mentioned in an earlier dispatch. They are in the western towns also, remodeling efforts designed to combat the financial flight of middleclass spenders to the mushrooming, dual-level, environmentally-controlled suburban shopping malls. With the middleclass also goes any city’s tax base.

Politically, I have noticed differences in eastern states’ communities and those of the South and the West. Most cities, at least the smaller ones in New England, still very much cherish their right of self-government and display that concern by holding and attending regular town meetings.

Community issues and decisions are hashed out at these sessions, which often last for hours. We found a lot of people living in the East to be fiercely patriotic, but strangely willing to chuckle at political corruption. For instance, a fellow named Al Greenstein of Toms River, N.J., told me about a mayor in that state who had been recently convicted of a felony bribe charge, but who was also re-elected afterwards.

Although some smaller towns in the South and West still hold community meetings, for the most part, I found them managed by mayors and councils or city managers and boards of directors. That’s not to say there weren’t also those in the East. There seemed to be less direct participation in local affairs.

The farther westward we drove, it became noticeable that people were more apt to speak to us as strangers, to carry on conversations and to smile back when we did. I believe it has something to do with the distances between cities. I mean along the East coast all you see are people and cars. But in Iowa, the Dakotas, Wyoming and Montana you often drive long stretches without even seeing another human being, much less talking with one.

When you do arrive in a town, most are less than 15,000 population and you generally stick out like a duck in the hen house. People will ask you where you’re from and why you’re driving a portable house and on and on.

A fellow newspaperman named Don Pugnetti, editor of the Tacoma Tribune, spent more than a decade in a small east Washington town and we talked about the differences between Americans living in small communities and those in the urban areas.

He said he believed people are much closer emotionally and tend to rely on each other much more in smaller towns. Of course, that was no revelation but it did make an interesting point. He said, as we have found, that people in the villages of less than 10,000 have far fewer commercial services. Consequently, they have to use initiative for such things as entertainment.

“This means planning bridge parties in the homes,” Don said, “planning for dances and decorating ourselves. I remember in that small town one year how I worked my tail off decorating for a dance that couples in the town were throwing. But when it was over, I realized how much I’d enjoyed doing for the group.”

“A few years later, two new motels went up in town. Both had convention facilities with big elegant rooms that we couldn’t really decorate for a party, and the parties lost a lot. They lost the human touch, the effort that made it all worthwhile. They just weren’t the same anymore after that.”

It does seem that as towns acquire more and more services, residents tend to rely less and less on each other for support. When a nightclub or movie theatre is a ten minute drive from the house, why bother to labor over plans for getting together with other folks in a less commercial atmosphere like a home?

Perhaps this is where the image of poor, dumb, small-town yokels at their quaint little town dance originated and spread to become joke fodder for those surrounded by cultural and commercial opportunities. But the question, it seems to me is who is the real loser in the realm of meaningful existence.

Don made another observation along this line…also a perceptive commentary on life in America today. “Not long after I moved to the Seattle area, I stepped onto an elevator in one of the big office buildings downtown,” he said. “Well, this other fella got on too, and it was real crowded. When the car started up, he began talking about what a pretty day it was and how good he felt and how he hadn’t had a bit of trouble on the freeway that day and so on. Well, no one said a word, not a word in response to the guy.”

“Like me, they all thought he was getting ready to come on with some pitch about selling us something. You know, like he had an angle for all that talking. But when he got to his floor, he said bye and stepped off. The door closed behind him and I never saw him again.”

“It might sound like a silly story, but it was a good example of how people are afraid to trust other people in an urban area. If that man would have been in a small town, you know good and well someone would have spoken back to him. Even me, direct from a country town, was thinking he had to have an angle for being so happy. Isn’t that ridiculous?”

In comparing states and regions, we have been continually surprised at how terrain is in many ways similar across the U. S. Parts of Maine can pass for Iowa, Indiana, Arkansas or eastern Washington. Virginia’s trees and rolling hills could easily be labeled Tennessee and few travelers would know the difference.

Much of the Midwest looks alike. After all, a grain field greatly resembles a grain field whether it be in Minnesota or North Dakota. Even towns take on similar appearances after seeing a thousand of them. First the gas stations, followed closely by motels and fast food places behind which lie the residential areas. If you stay on the highway far enough, there is the downtown section and a repeat of the businesses going out the other way.

The state of Washington was particularly surprising to me, along with Idaho. All my life, I had pictured Washington as a green state filled to the brim with towering pines and rugged mountains, which is exactly what I found in the western section. But in the eastern half was desolation rivaling that of eastern South Dakota…miles and miles of nothing but rolling brown dirt and a few rocks. There were almost no trees for as far as I could see. Residents of western Washington call them the scablands.

Idaho, on the other hand, had always been a brown, potato-farming state in my mind. I’d never imagined it to be largely a wilderness area loaded with elk, moose and other wild game. It is the southern section, which we didn’t see, that supports the starchy vegetable.

If our journey thus far has shown me anything about America and the people who live here, it is that we are increasingly becoming a nation of migrants. Time and time again we have talked with families who had either just moved to a town, or were preparing to leave. Elderly couples are giving up houses and apartments in record numbers to purchase motor homes and trailers to roam at will. We know, we have talked with them night after night on the road.

Campgrounds from Maine to Washington are having record-breaking months and it’s not only due to the Bicentennial. According to several managers, the nomadic boom began two years ago and has been steadily increasing ever since. I believe it is a combination of factors, including the restlessness that goes hand-in-hand with frustration and skyrocketing utility, food and you-name-it bills responsible for the get-away trend.

Only a few decades ago in the small and medium-sized communities, families had deep roots that stretched far back into the founding of particular counties and towns. Today, their offspring by and large have left those places in search of livable wages. Although there seems to be a more recent trend where some of those are frustrated in the urban places and looking for ways to escape back home. It could be that we are in the early stages of a process whereby our population will become more evenly distributed.

There also seems to be a trend in many cities to consolidate community and county law enforcement. I talked with a young policeman in Richmond, Va., about the recent combining of locality and county departments and he said he felt it was an inevitability throughout the nation. As we moved westward, I also found this happening in smaller towns like Custer, South Dakota and there is talk of uniting the city and Sheriff’s department in Seattle, Washington.

The primary hurdle in such consolidation lies in political hassles as might be expected. After all, who’s going to head the county department…the Sheriff or the Chief of Police? In the cities which have made the changes, it seems to be working well as do the thousands of women police officers now being hired in virtually every larger city. We watched a female officer frisking a large man on the street in downtown Seattle and she wasn’t having a bit of trouble. As a matter of fact, she had the suspect’s arm twisted behind his back and his face was drawn with pain.

As far as there being any mood of America within the states we’ve seen, well, I seriously doubt that Lou Harris or any other pollster can accurately pinpoint the feelings of people in America on any given day…much less a journalist from the hills of Arkansas.

But we have spoken with hundreds of people about their feelings and predictions for America and they have been largely negative, cynical and frustrated in their responses. For instance, there was a retired school superintendent of 18 years in South Dakota who was not ruling out the possibility of a revolution in America should the nation continue on its present course.

He was a mild, soft-spoken admitted conservative who said he simply couldn’t deny his true feelings any longer. “With the bureaucratic mess in the United States today, where an individual’s ability to maintain a private enterprise without being stepped all over and dictated to by some oaf in a gray suit behind a federal desk, the way it is, I see no hope for any improvement or change short of an uprising.”

Another good example of this feeling was along the outer banks of North Carolina where we talked with residents who were literally being held prisoners by the Department of the Interior which was telling them when they could use a road to travel to the grocery store, doctor’s office, dating and anything else they cared to do.

The reason, given by another bureaucrat, for only allowing the people to travel on the highway during restricted hours, was because the birds which inhabit the island were being mistreated. The families we spoke with were more interested in their rights as Americans.

The disgust and disenchantment appears to have spread to all forms of institutions. Many people sincerely believe that honesty and integrity have outlived their place in our society and now the passwords to success are cheat and deception.

This sweeping negativism has seriously disturbed me. But then I’ve been described by one Washington editor as being incredibly starry-eyed and wide-eyed, so maybe I was meant to be baptized in the fount of realism and despair. To me, the very principles upon which the nation was founded seem to be faltering in this Bicentennial year.

Without such idealistic virtues as trust, honesty and integrity, our system, it seems to me, begins to drip the lubricant that keeps it flowing smoothly until it finally throws a rod and ruins the whole engine. If I’m suspicious of my neighbor’s every move and he likewise, how is it possible to work together toward common goals, or solve common problems that threaten not one, but all?

I sense a desperation in the people we have talked with, which might account for the overwhelming popularity of smiling Jimmy Carter and the phenomenon of his rise to national prominence. Americans see the smile of John Kennedy under a big nose. They see his suit of armor untarnished by the corrosion in Washington and they see him as an alternative to the way things have become.

However, they also feel the pangs of frustration because, like I said earlier, there is this fear inside, a fear to trust or believe anyone, especially a person running for President who contradicts himself.

As Senator J. W. Fulbright once told me when I asked him a question about the outcome of the Vietnam War…”I’m no soothsayer, I can’t predict the future young man…” so it is impossible for me to accurately evaluate where this country seems to be headed based on the feelings of many Americans.

Perhaps as our journey enters into its latter half in October, my perspectives will have again changed. America, or I should say all of our Americas, seem to have a way of doing just that.

Received in New York on September 9, 1976

©1976 Mike Masterson

Mike Masterson is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Sentinel Record (Hot Springs, Arkansas). Mr. Masterson will travel throughout the U.S. with his family and write about the country and its people in 1976. This article may be published with credit to The Sentinel Record and to Mr. Masterson as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.