MONTGOMERY, Ala. — Winding the car along neighborhood streets, I watched the old, two-story white homes glide past. This had all the earmarks of a vintage city smack in the vitals of the deep South. There was some comfort in realizing we were back in the South again. It was a feeling I can’t describe except to say it was generated by a slower, less frantic pace.

Here, people walked the streets like it didn’t matter if they were five minutes late. In the cafes they ate slower and there’s no need to describe the way folks drag out their words in a drawl.

Not far from the gleaming state capitol dome and around a couple of corners from where Martin Luther King, Jr., once preached the message of human rights on Sunday mornings, I happened upon a federally-subsidized housing project.

You know the kind, identical, two-story red-brick buildings that spread for blocks. It’s the same place I’ve heard others call “the only sore spot on our nice little place to live.”

There must have been 40 or more young black children playing on bicycles beside a busy three-lane street that bounded the project on one side. They were taking turns soaring a few feet off a wooden plank that was tilted with the help of a broken chair.

I found a parking lot a block up the street and walked back amid the crowd of smooth ebony-skinned faces, fully expecting at least a few frowns of hostility. But they weren’t there.

The children, most I judged to be ten or less, gathered around closely and touched my jacket and camera. They wanted to know who I was and where I was from and why I was there on that blue-sky Saturday morning and would I take their picture? “’cause no one’s ever taken it before…”

Then it was my turn and I asked names. I met Robert and Willy and Mike and Kenny. Tommy had a runny nose. I wondered about their bicycle game and what each wanted to be when they grew up. Their answers came in unison, “a nurse, a SWAT man, a fireman, a race car driver, a doctor, a taxi driver…” A petite girl named Mona tugged at my pants leg and said she wanted to be an actress.

As all of us sat on the threadbare grass of the narrow front yard, a blue car swerved off the one-way thoroughfare and stopped about two feet from my right foot. An attractive young woman climbed out from behind the wheel and aimed a pensive stare in my direction. Three children also left the car and ran into the crowd.

“What could you be taking pictures of around here?” her tone was one of genuine curiosity. I explained how we’d been driving by and seen the kids playing and how I’d just felt the urge to join in for a while. A smile spread across her face. “Man, you must be crazy or something.”

Her name was Betty McNeil, a 35-year-old native of Alabama and the granddaughter of a slave. She had recently returned from two decades in New York City.

Her husband, Chippy, was a long-haul truck driver who got home only a few nights each week. They had three daughters and a four-year-old son.

“The girls live here with us,” she said. “But our little boy has to stay with my mother during the week since we can’t afford a babysitter all day while I’m working. Mom lives about 50 miles away. We get to see him on the weekends.”

By this time Kathy had joined us and Betty insisted we go inside for a cup of hot Ovaltine, which was an instant drink somewhere between the flavors of coffee and hot chocolate.

The three-bedroom apartment was broken into two stories. We gathered around the kitchen table and Betty excused herself to fiddle with a stereo radio until the sound of rock music blared from the speakers.

Returning to the table, she continued her story. They had left New York ten months earlier where she had been a highly-paid secretary. “We made a lot more money then,” she said, “but then a tiny apartment in Brooklyn cost us $225 a month, too. It was one of those places where you could stand at one end and see the whole thing.

“Finally, we just looked at ourselves one day and asked if that was what we really wanted. It wasn’t and we decided to come back to Montgomery. I guess the weather had something to do with it, too. An awful lot of our friends have left there to come back South in the last year. It’s just too cold, especially after this winter.”

Betty spoke in very proper dialect. A gold scarf was pulled around her head and tied in the back. I sensed her return to Alabama had held disappointment, “I sometimes Think about returning to New York,” she said. “The educational advantages there far outweigh what’s here. Children have more opportunity to learn — things like field trips and individualized attention when they need it.”

“For instance, my daughter goes to school here with 30 other children in her room and only one teacher.”

Betty had recently started working in a garment factory and told me racial bigotry is still alive and well in Montgomery.” I’m fully qualified to be a first-class secretary and I applied for several positions in that field when I first came back. Over the phone they were interested, but when they saw I was black it was all over.”

“I’d never worked in a factory before. It’s strange and boring work to me but at least it’s income and everyone there is nice.”

They pay $65 a month plus electricity for the apartment and she said only one neighbor has made an effort to befriend them since they moved in. “But I suppose some of that is my fault. I have to make an effort too. That’s part of New York lifestyle that’s stayed with me, not getting close to neighbors. I don’t even know who lives next door.”

I asked if she’d return a moment to the bigotry she’d encountered in Montgomery and if she’d felt any of the same in New York. “It’s a different kind of intolerance in New York,” she said. “There, it’s based on how much money you have. Here, it’s still skin color or religious faith.

“We met a nice Jewish couple not long ago who had also been given the cold shoulder because they are Jews. They’re probably our very best friends here.”

“But you have to understand something else, too,” she continued. “I can see unfounded bitterness in these kids right outside. It all comes from hearing their parents lay around and moan about what-all whitey has done to them. Some of those kids are learning to hate other people just because they don’t look the same. That’s wrong.”

Her gaze dropped to the tabletop and she sipped from the steaming cup. “I don’t believe in that at all. I try to teach my children that color doesn’t matter in the least. It’s strictly the person on their own merit and that’s how they should react to others. Take the movie ‘Roots,’ for instance, it’s juvenile to blame an entire race for something that happened 200 years ago. Did you know there are some in this project who do nothing but lay on their fannies and watch TV all day. They get up just long enough to gripe about how mistreated they are then run down to the welfare office and get their hand-out money that I’ve worked to give them.

“That just isn’t right. Me, why I’m a hustler, a creator. I gotta be out doing and making for myself. God gave everyone a talent and living off what I’m working to earn is no talent.”

She rose from the table and showed us through the cramped but clean apartment. The walls were covered with decorative pieces she’d made. At one point she stopped and took a colorful peacock feather from an arrangement, handing it to Kathy. “Take this as a small gift,” she said. “I want you to have it.”

After more than an hour’s conversation and three cups of Ovaltine, we walked to the front door and looked out. The children were still playing on the sidewalk. “There have been three kids hit and one was killed by cars during the last two years,” she said. “The cars come flying over that hill and race down without looking.”

Stepping outside, I asked Betty a parting question about the future of race relations in America and her feelings. She said skin color will be inconsequential within 50 years. “There will have been so many intermarriages and relationships,” she said, “that it won’t make any difference. I really believe that.”

As for her future, well she just grinned and said she was going to keep on hustling and doing for her kids and all she wanted was for people to treat her the way she treated them.

Thanking her, we stepped outside and were immediately surrounded again by the children. They followed us to the car in a great, animated, rambunctious horde. Mona grabbed my hand and held fast until I reached the door.

Every one of them waved and shouted as the car backed out and I snapped a last picture before we drove back to the Lady K.

PLAINS, Ga. — I had to overcome an urge to bypass Plains altogether even though we had parked the motor home less than 50 miles from the town.

Perhaps my reluctance lay in the realization that so many of my colleagues had been there ahead of me, gulping the oasis of stories bone dry.

But in the end I decided it would probably be the only time we’d be that close, so we unhooked the car and set out through a steady rain across the rolling fields of western Georgia.

Driving into Plains and seeing what’s there is sort of like eating just a few peanuts. You’d like to have some more, but an hour later you’ve forgotten you ate them. Two years ago, the town was just one of those little spots beside the highway where you slowed momentarily to avoid leaving a contribution with the local Justice of the Peace.

Those days are memories. The promoters and speculators are thicker than corn stalks and you’ve only to see the tour business, peanut shops, antique abodes and boutiques to realize it. Despite all the frills, however, the biggest attraction, complete with custom-painted sign, is brother Billy’s gasoline and service station.

It’s about a mile down the highway from the President’s house, which you can see from the highway while you’re driving by. Signs on both sides warn motorists not to stop as you’re passing.

The only parking spot at the gas station was in a mud hole to one side. Cars from five states were lined up at the pumps.

Billy, some man told me, was out-of-town for a few days, something about a business deal with a press agent. So we mingled with the crowd and stared at the clutter strewn in every direction around the small wooden building.

Several young men were scurrying between the pumps and the station. Not one smiled that I ever noticed. An older fellow did say they had pumped 9,000 gallons of gasoline in one day during the previous week.

The station inside was also in disarray and unclean. Kathy called it dirty. A couple of cheesecake calendars were taped to the walls and an upside-down closed sign dangled from the weather-beaten door.

The men’s room was out of order. Kathy excused herself and returned in less than a minute, saying the ladies rest room smelled too bad to even attempt an entry.

Evidently, the good ole boys immortalized by television reporters had retired from their couches in the station lobby. All but one, that is, who sat with his head buried in the morning paper. A black pooch snoozed at his feet.

Walking across the street past a half-dozen tourist shops, I spied a gathering of black men huddled in front of a dilapidated building behind the city grocery. Deep in conversation, they occasionally would glance toward the dozens of picture-snapping sight-seers and chuckle a bit before returning to their discussions.

They were wearing overalls and khaki work clothes and seemed friendly enough, so I walked over and interjected myself into the group.

Three were receptive and the other four stared blankly across the street after I’d explained who I was.

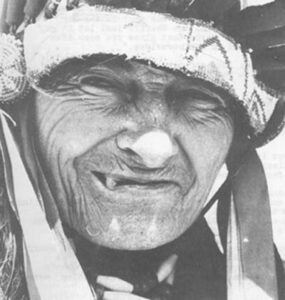

The man who smiled the broadest was Leonard Wright, who happened to be a sharecropper for the Carter family and had been for 23 years. A man of medium build, curly hair that grayed at the temples and bloodshot eyes, Leonard seemed glad to talk about Plains and his life there.

He was born in Sumter County, Georgia, nearly 60 years ago and first went to work as a field hand for a doctor who lived near Plains. His older brother, who has since died of cancer, was then working for Earl Carter. “I worked for the doctor a short while,” he said, “then I asked another field man who worked for the Carters if he’d trade with me so I could be close to my brother. He said yes, so we traded.”

That was in 1952, he said. A short time later Jimmy came home from the Navy to run the farm’s warehouse after Earl, his father, had died. “I got pretty close with Jimmy then,” he said. “Matter of fact, I still can’t call him Mr. President. It just don’t seem right.”

We stood with our shoes in the red clay mud talking about the town and his favorite fishing hole along the Chattahoochee River until Leonard said he had to get back to his house, about six miles from town. He explained how he was single-handedly planting and raising 100 acres of corn and 100 acres of peanuts that he split down the middle with the Carters.

“They provide the seed, land and fertilizer and I give the machinery and the muscle work,” he said with a laugh. “Say, if you’d like to come out to the place with me, I’d enjoy having ya. It ain’t nothing special but you’re welcome.”

We followed him along a paved road that led into the flat croplands for about five miles before he turned left on a narrow muddy passage that eventually lead to a gray clapboard house and a shed filled with farm equipment.

Leonard’s house looked comfortable and there was no mistaking his profession. We had seen thousands of such homes in the fields beside highways from Maine to California.

Across the road was a large fenced pen filled with more than 30 hogs and pigs. He said he raised them for meat on the table, not to sell.

Curious about his wife and family, I asked him to talk some more about himself. He fired up a filterless cigarette and inhaled deeply.

“I didn’t go no further than the eighth grade in my schooling,” he said. “I left that Negro school and went to work on the farm.”

“Mary, my wife, and I met in church one day and we dated around about three years before marrying in 1950. We got us five kids now all the way from 17 to 26. Guess that’s about all there is to tell. Shucks, I ain’t nothing special for sure.”

I asked if his children were working in the fields. “No sir they ain’t,” he shook his head from side to side. “They every one finished high school and all but the youngest has been through college. They got better things to do with their lives now.”

He went on to explain how he still had a few more acres of corn to gather, but the fields were too wet from persistent rains of the past week. “I’m hopin’ the weather will be right to get the peanuts planted on time this year. I’m hopin’ every night and day.”

Leonard’s dreams were simple and undemanding. “I once thought I’d like to have my own place, you know, my own farm and all. But when the time came to put up or shut up, I was just afraid to make that kind of investment. I’m satisfied with things like they are now.”

“I’ve got me three rent houses in town, so even if I ever gets kicked off of here, we won’t be out in the cold.”

When he’s in the fields, Mary is busy stitching shirt collars at a factory in Americus, Georgia, 15 miles up the road. He said she leaves early each morning and returns about dark, “in time to fix dinner. I don’t do that. Then we generally watch a little TV and go on off to bed.”

While standing beside the pen, a herd of the pug-nosed animals had edged to within a few feet of the fence and were eyeing us to an accompaniment of grunts and snorts.

I yelled boo and they squealed, jumped, gasped, flipped, oinked and fell all over themselves trying to get away. “Them’s fidgety critters,” Leonard said. “Sometimes they keep us up all night rootin’ in that metal feeder over there. It makes the dangdest noise you’ve ever heard.”

Later that afternoon, he told me about an experience with Jimmy Carter that meant more to him than any other over the years. “It was back in the 60’s when all the trouble about integratin’ the schools was goin’ on,” he said.

“Well, some of the landowners got together and agreed that if any of their black sharecroppers sent their kids to the white school in town, they’d just up and fire ‘em.”

“Not knowin’ what I should do, I went to Jimmy and told him about what we’d heard and asked what we should do. I wanted to know if he was in with ‘em and if I’d lose my job.”

“Well, sir, when I told him, he looked me in the eye and told me what we should do was everyone of us get together and send our kids all at once in a group. That way, we’d be a lot stronger than if there was just one or two. He said they couldn’t fire all of us.”

Leonard said the families took Carter’s advice and things passed without incident. “But I know for a fact that Jimmy lost some employees at the warehouse and a lot of business over that advice,” he said. “He said at the time that he expected to lose $10 or $12 thousand because he felt the way he did.”

The overcast sky, which had earlier brightened, had just as quickly returned to pewter and fingernail-sized silver droplets were again spewing from the clouds.

I shook hands with Leonard and wished him well. He said I should wish for three days of clear skies so he could go back to work.

VENICE, Fla. — I had counted 42 traffic lights along the 50-mile stretch between Tampa and this small Gulf coast city. The bumper-to-bumper river of shimmering tin flowed around the Lady K, stretching into the distance for as far as I could see.

When impatience had me screaming at myself, I bucked the cross current and dropped anchor in the concrete port of a shopping center.

There, I switched off the ignition and leaned back in the padded seat to mend a few frayed nerves while Kathy set about brewing a pot of coffee.

In a few minutes I opened my eyes and peered through the windshield across the highway. On the other side was a green expanse dotted with tiny triangle-shaped flags. The fairways were bounded on one side by a grouping of tri-level condominiums mixed with others of the same color that were built on the ground, similar to duplexes.

A sign at the entrance said “Bird Bay Village.” Several flocks of gulls swooped and circled overhead, screeching their unique cry.

Being grits and cornbread born, down where most folks have bonafide houses with yards to occupy weekends, I’ve always held a natural curiosity about those whose identical homes are stacked neatly atop each other.

So the staring continued and my thoughts turned to those who come there to live. “I wonder what it’s like over there?” My voice was just above a whisper.

Kathy leaned over for a long look out the kitchen window. “I read an article that said that’s how everyone will be living in America within 20 years,” she answered.

The second cup went down quickly and I spent another ten minutes quietly studying the layout before sending a rumble of life through the Lady K with a twist of the key. This time we were only going a few hundred yards, across the motorized torrent to the condominium office.

I’d decided that strangers are only strangers if you never meet them and we were about to become temporary residents of Bird Bay Village.

A congenial red-haired woman named Lucy assigned us a vacant apartment on the ground floor of a high rise we’d been watching earlier. “The people here are having a party this afternoon,” she said, handing me the key. “Why don’t you come down and meet some.”

There were four modern three-story buildings where we unloaded the coach, hauling out in our usual Grapes of Wrath fashion six or seven brown paper bags crammed with everything from torn Fruit of the Looms to stale Ritz crackers.

Each apartment had a carpeted and screened porch. Several residents waved from theirs while inspecting every move. Apartment 111, recipient of our sacks, had two bedrooms and was decorated as nice as we’d ever seen.

We decided to attend the party, but I had earlier spied an interesting fellow in a Panama hat, Bermuda shorts and a lot of wrinkles who was playing with a small boy in the next-door garden.

The slender man’s named was Cob, short for Colburn, and his tiny companion was Keith. They had spent an hour planting and picking and digging and just generally having a good time together in the dirt. Keith, who was three, belonged to a younger couple from a villa-styled apartment a block away.

Cob claimed Keith was a good friend who often peddled his plastic Big Wheel tricycle down the street for an afternoon visit with the elderly man and his wife.

Standing in the comfort of mid-70’s temperatures, I listened as Cob explained how he had been in utility management all his life and had once managed the natural gas company in Fredericksburg, Virginia, for several years.

He and his wife, Peggy, a former secretary to the late Wendell Wilkey who once ran for President, had come to Bird Bay from Connecticut three years earlier. “We came when they were building this place,” he said. “We’ve seen it grow from the ground up and it’s unusual. There’s no place else like it.”

“Tell you what I mean,” he continued. “Not long ago, Peggy was hospitalized and she got more than a hundred cards from people right here. Some came from people she’d never met, but they knew her and cared enough to wish her well.”

Reaching down, he scooped up a handful of earth. “I love the garden,” he said. “In the summer time everyone gathers at the swimming pool to solve the world’s problems. But during the winter and early spring, we get together out here in the garden. It just seems like a natural spot.”

At the party, Kathy and I walked into a room filled with brightly-dressed people who were laughing and talking in groups of four or five. Being total strangers and the youngest there by at least 20 years, we felt like two tadpoles at a bullfrog convention.

Glen Miller Orchestra Favorites revolved on the well-used Hi-Fi. Beside the record player on a long linoleum counter was a row of empty paper sacks that looked vaguely familiar. This was one of those parties where each brought his own liquid refreshment, mixer and snacks.

The only thing provided was a place and the fellowship, which was what they had all come for to begin with.

I’d been staring out the plate glass window feeling ill-at-ease for less than a minute when a number of older people began introducing themselves. We met Mary and Bob McEvoy, formerly of the Bronx, who came to Bird Bay from an apartment where they’d lived 40 years.

“We came down to visit friends who had moved here about two years ago,” she said. “Bob had always ranted about how he’d never like living in something like a condominium, but we were here less than a day when he decided to retire and move down right away.”

Bob was a retired carpet salesman who had worked hard for 53 years. Now 71, he said he just wanted to spend a little while enjoying himself before it all ended.

“New York was getting real bad,” he said, “especially our old neighborhood that used to be so nice. Three women had been murdered around us within a year, right in their apartments.”

Never needing a car in New York, Bob was studying to pass his driver’s license test in Florida so they could buy a car. “I haven’t driven since the 1950’s,” he said, “when I had a company car.”

I also met Aurora Day, the librarian at Bird Bay and her husband, another Bob. He was a retired auditor with the Maritime Commission. She had been a secretary to the president of a New York City bank for many years.

It was the Days who enticed the McEvoys and three other couples to the condominium during the past three years. “And every one of them were card playing friends of ours in New York,” she said, “I guess you could say we just moved our game down here. The owners of this place should be paying us a commission or something.”

Then there was Art Nightengale, a well-dressed man with a pointed nose, lip-line mustache and the capacity for lengthy conversation about his profession, which was selling flowers.

He started by telling me held never heard of a flower merchant who’d ever made a million dollars just from selling flowers alone. “It might seem like a business for wealthy people, but it isn’t. Oh, now I made enough to live comfortably on but that’s all. After 50 years of it, by golly, I don’t feel the least bit guilty about enjoying myself.”

He raised a Pina Colada drink in a toasting gesture, tilted his head and smiled before downing it in a single gulp.

After 30 minutes, Kathy and I were becoming fast friends with several in the milling crowd. Guffaws and witty jokes were on the increase by the time we eased around the linen-covered hors d’oeuvre table.

An athletically-built older man who called himself Jack Jackson began talking to me as I thumbed through a tabletop copy of Modern Maturity magazine. He was clad in red pants with a white sport coat and a gold chain around his neck.

He’d spent a career with the U.S. Foreign Service, the waning years of which were at the United Nations. He’d been a former football star at St. Bonaventure College and he explained in detail about his years as a soldier during WWII.

Jack was at Bird Bay for a few weeks then he and his wife were going on to Ft. Lauderdale. “I’m not sure where we’ll settle just yet,” he said. “We’re just looking for a few weeks.”

He was most proud of his daughter. “She’s worked to become one of the few women experts in the nation on oil spills,” he said. “She works right alongside all those men and they respect her, by gosh.”

Our conversation ended abruptly when I made the mistake of asking whether working for the Foreign Service meant the same as the Central Intelligence Agency. A strange expression spread over his tanned face and he hesitated before answering. “Why do you ask that?”

Shrugging my innocent shrug, I smiled. “Just curious I guess.”

“Well, no, not really. I was with the Foreign Service, not the CIA.”

Actually, I had liked Jack and was a little sorry I’d asked the question because within a minute he had faded into the melee never to be seen near the hors d’oeuvre table again.

There seemed to be very little difference in these party-goers and those of our age, except that these people were more at ease with themselves and toward us than a younger group might have been. I found I could identify with practically every person in some way and they with us.

It was sobering to realize that, except for aged bodies and a wealth of experience and impressions, these were the same people they had been 50 years ago, back when they were my age…a few weeks earlier.

Later that evening, I encountered one of the most interesting characters at the village. His name was Ralph and he was a handyman-security guard for the condominium.

Like most who stay more than a week, his skin was brown. The disposition I can only describe as downright irreverent but likeable.

“I’ve got my own spot for people like you,” he said at our first meeting. “My father was a managing editor and my former wife is writing a book, so I’m no stranger to the business and I say your profession has died and gone to Hell in the last 20 years.”

“All the editors do nowadays is rip the wire and write headlines. There, is no digging to speak of anymore, not like back when journalism was really journalism and newspapermen had some guts about them.”

I dared not argue with Ralph since his handsome silver goatee, substantially-creased face and small, sad bassett hound eyes gave him the look of unbridled philosophical authority. Besides, I couldn’t get a word in edgewise.

During our stay I often saw him scooting across the grounds on his tiny yellow motorbike or absorbed in helping some resident solve a problem. He had been there more than two years after retiring from a sales job held held 32 years.

“I sold seats,” he said one morning. “You know, seats for buses and trains and even for Yankee Stadium…darned unusual job.”

A professed Gypsy at heart, he said he had just moved from one of the furnished apartments into a cubbyhole at the rear of the social center. “I’m a dad gummed wandering spirit and I’m happiest like that,” he said with a draw from one of those long green cigars he always smoked.

“Take a place like this,” he continued. “This is where the elephants go to die. For most of these folks, this place symbolizes final resignation, withdrawal from the grind. They’ve got everything they need here so they come at the end to check out.”

From what I’d seen of Bird Bay, it seemed to me to be more a place where people who had worked their lifetimes away could escape to polish a while on the memories and accomplishments of that life, a place to savor the multitude of good moments and try to synthesize it all into some kind of meaning.

Here, my nostrils were filled with pleasant smells from ocean breezes and green growing things rather than the stench of Ralph’s suicidal elephants.

Mostly what we saw during the week was a lot of living and activity that even included several younger families who’d purchased homes at Bird Bay.

An irony in this community for retirees was that it was managed by a tall, slender collegiate swimming star who was only 26.

Ken Cheezem had managed the complex for slightly over a year after his father, Charles, moved him into that position from a family business called the Cheezem Development Corporation.

A smooth-talking, personable man, Ken told me he started working for his father when he was only 12. “I’d sweep up after school and on weekends,” he said. “That was in St. Petersburg.”

Ken found the job as manager personally fulfilling but sometimes frustrating and often frantic. “Occasionally I feel tied down,” he said, “primarily because of red tape like zoning restrictions and ordinances. But I guess every job has its frustrations.”

I wondered what kind of people buy homes at Bird Bay. “We had 40 sales in 1976 and almost all were from the middle class,” he said. “Most came from the North or the Midwest and East, although there are a large number of local people who buy, too.”

“We spend about $3,000 a month promoting the village. The best dollar spent for us is with billboards, because if a couple is driving along the highway with living here in mind and they see the advertising beside the road chances are they will stop and look.”

He said there are people who come to rent only for the winter or a short time. “About one in every 15 who comes through the door looking will actually buy a place at Bird Bay,” he said.

“At first, they seem to like the social atmosphere, golf course, tennis courts, pool and that sort of thing. But after they settle in and make friends, the emphasis seems to shift in that direction.”

Ken was born in Augusta, Georgia, but moved to St. Petersburg after two months. He grew up there, graduating from high school and going on to college at Principia in Illinois. It was there he met, Anne, his wife.

“She cornered me in the dark room after class,” he said laughing, “and showed me her camera and pictures.”

During our stay I met more people than it’s possible to relate in this dispatch. Two of the most memorable were Damon “D.A.” Willbern, founder and past president of the Coffeyville, Kansas, First Federal Savings and Loan and a retired minister from New York named Harold.

D.A., who was 77 and well into enjoying his retirement, invited me to share a few afternoon rounds on the golf course with him. I believe he came to view me as an adopted son of sorts.

We continually laughed and teased each other and I enjoyed our brief friendship enormously. He was a Teddy Roosevelt look-and-sound alike who regularly used words like “splendid, fine chap and bully” in a deep growling voice that started way down in his throat.

He and his wife, whom I didn’t meet, were at the village for the winter.

He told me he just tinkered around back home in Coffeyville. “I’ve got a little office downtown for investments and such.”

Harold was a 74-year-old retired Methodist minister who had spent one career with IBM and another with the church.

A totally open man, he told me about a struggling time in his life when unkind comments from his children sent him to the brink of suicide.

“Things weren’t going right for me,” he said. “My unrenewable life insurance policy was scheduled to expire in a month. I was out of work and it seemed everyone was down on me, even at home.”

“Dead, I was worth $10,000 to my wife and kids,” he continued, “and

the children said something to me at the dinner table one night that led me to seriously consider suicide as a way out.”

But his final decision was to continue living and try to rise above the hard times. Afterwards, things got better for Harold. He said he became a lucky man who had found happiness and satisfaction from two totally different professions.

He didn’t enter the ministry until he was 45 and then spent ten years working with IBM and the Methodist church at the same time before leaving corporate life.

By the time those same wrinkled bags were stuffed back into the Lady K, I’d been able to see at least a bit of what was behind that front gate along U.S. 41 in Venice. It was a time that forced each of us to recognize values we hadn’t considered before.

But a roving journalist isn’t really a roving journalist unless he roves, so we reluctantly drove past the front gate at Bird Bay and wheeled southward toward Miami.

MIAMI, Fla. — After an hour’s walk along Eighth Avenue, the Cuban section of the city, the blonde who travels with me and I decided to sit for a while and watch several dozen Cuban men play dominoes.

The games were underway in a small park beside the avenue and it was obvious this was a daily ritual for most of the older fellows hovering over the concrete tables.

Eighth Avenue was a vibrant yet rustic part of the oceanside city known for so many tall, white buildings. I’d felt like we were in Havana as we strolled the sidewalks listening to dark-complexioned people rattle off Spanish on each side. Even the stores felt somehow foreign.

A friend at a Miami newspaper had told me no one could go to Eighth Avenue without sampling the strong Cuban coffee and little pastries from any of the open-air counters.

The street is lined with open counters and windows where you can walk up and start eating and drinking. But one small glass of the bitter coffee was more than enough for this gringo. Kathy took two sips and cried uncle. The pastries were something else. We each downed three.

Miami is much more an International city than I’d imagined. During the afternoon we’d seen Arabs, Puerto Ricans, Japanese, several Indians and, of course, thousands of Cubans. Miami beach was probably the biggest disappointment.

We had parked the car and hurried to the retaining wall for our first glimpse of the famous sand, but the sand was almost gone. Only a few people were braving the high 60’s temperatures on a beach that couldn’t have been more than 20 yards wide.

What caught my attention about the beach area were the large numbers of elderly people who sat on hard-backed chairs in front of the many beachside hotels. Like seagulls, they just sat in rows soaking in the sun, watching whoever and whatever passed by.

I met one woman during our stay who is probably indicative of most people who find a substitute for human love and companionship. We have seen so many throughout the country who transfer their attention and affection to the relative safety of a pet who can’t abuse or reject them.

It took 13 pills and an insulin shot to keep Joey up and about each day, which would be tough for a person. Betty Lockman, who lived on Eighth Avenue, had maintained that routine for two years to keep her 14-year-old mongrel pooch alive.

Joey is Betty’s roommate. She is an unemployed, disabled physical therapist who has never married and who considers the dog her child.

“Joey is like a child to me,” she said. “I get a lot of joy from him. He even understands me just like a human. I guess that’s why I named him Joey, after the movie. You know, the one called ‘Pal Joey.’ He’s my pal.”

Last year, Betty emphasized her devotion by paying about $1,000 from her welfare check¤ to a Miami animal clinic for treatment of Joey’s many afflictions. The ailments included an enlarged heart, decreased thyroid function, eye and ear infections and chronic tapeworms, bladder infections and skin rashes.

In 1970, Betty said all of Joey’s hair fell out and he went around the apartment bald for months.

Born the son of a liberated Chihuahua and an affectionate poodle, Joey was the only one of four in his litter who survived. Betty got him from her brother when Joey was six weeks old.

“He was the runt,” she said. “He was scrawny and scruffy and ever since I got him it’s been one thing after another just to keep his nose above water.”

In addition to the daily shots for diabetes, Joey also downs 13 assorted tablets ranging from Valium to thyroid pills and vitamins. Those she buys from a drug discount house. But then there are also the weekly trips to the hospital for routine blood sugar tests that run $6.50 each.

Betty told me it hurt her just as much as it did Joey to inject him every morning before breakfast. She said he still winces a bit when the needle enters his side or back. “It took a month before I could give it to him,” she said. “Held look at me like he knew I was about to hurt him and I couldn’t do it. He still psyches me out with his longing stares, but I believe his skin’s getting tougher.”

She said Joey sometimes lapses into diabetic coma and she keeps the cure close at hand. “I give him a teaspoon of Karo syrup whenever his eyes get glassy and he begins to stagger,” she says, “and he snaps out of it.”

His worst attack came after she’d been hospitalized for a few days and Joey stayed with a neighbor. “It took two spoonfuls to get him going when I got home. He just got so excited that he collapsed in shock.”

The curly-haired, tan dog will be 14 on April 10, but Betty said she hasn’t decided whether he’ll wear a costume for the celebration.

“He just loves to dress up,” she said, “and I enjoy putting clothes on him, too. Last Christmas I dressed him up in a Santa outfit and he was so happy. He also has a cowboy costume and a French beret with a fitted coat to match.”

She told me about a recent Halloween when she dressed Joey in his Santa outfit and let him go trick-or-treating with the neighbor children. “He came back with a bigger bag of treats than the others,” she said.

Betty’s total devotion to her dog was further proven a few years ago when she moved from the Bronx in New York to New Jersey where she had a yard and trees. “I only stayed a few weeks,” she said, “because Joey was allergic to grass.”

I had mixed emotions about her absorption with Joey. There was no doubt he brought fulfillment and motivation into what might otherwise be a barren existence. But there was also no doubt that someday soon, he will be missing in her life.

I asked Betty about that and she gathered Joey into her lap. “Joey has a girlfriend named Champagne and even though she’s only 14 in human age and he’s 98, the doctor told me he could still father a litter.”

“That’s what I’m hoping for. One of his puppies. The only thing I worry about is that Joey might have a stroke or something while it was happening and, well, you see he’s never done anything like that before, poor thing.”

She pointed to a portrait of Joey hanging from one wall. “I’ll always have that to remember him by when he goes. If he doesn’t sire a puppy, then I guess I’ll just keep the two cats I have.”

Before we left, I told Betty I’d like to keep in touch by letter. She smiled and nodded.

Received in New York on March 28, 1977.

©1977 Mike Masterson

Mike Masterson is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Sentinel Record (Hot Springs, Arkansas). Mr. Masterson will travel throughout the U.S. with his family and write about the country and its people in 1976. This article may be published with credit to The Sentinel Record and to Mr. Masterson as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.