Seattle, Wash. — The city of half a million is snuggled beneath the guardian eye of snow-capped Mount Rainier, a spectacular granite wonder that stretches for and grasps low lying clouds.

The Lady K rested in the woods at the KOA campground near Tacoma while we three piled into our four-wheeled lifeboat early one morning and headed for the city’s heart, 35 miles north.

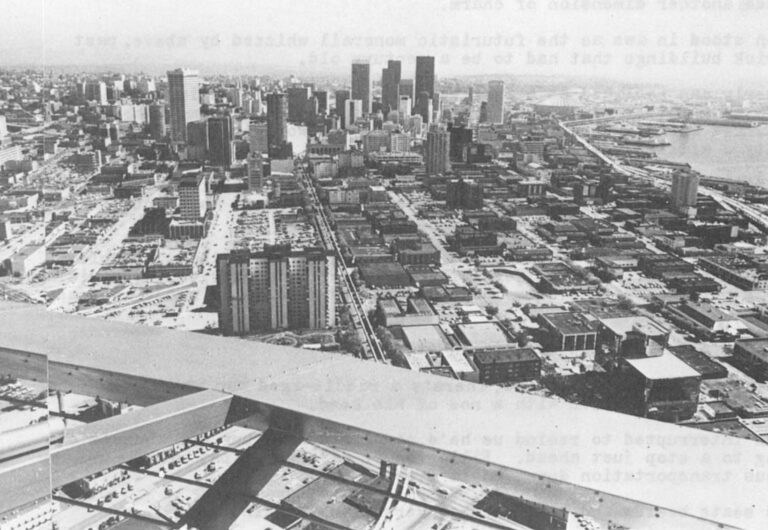

From a distance, Seattle resembles most other large cities. Gray rectangles of concrete and stone rise above the landscape surrounded by ribbons of interstate and a swaying sea of brightly-colored tin, each spouting its foul-smelling charcoal exhaust into the air.

But up close, along the sidewalks, the view changes. Seattle becomes a blend of old and new, of excitement and even romance. Steep hills traverse the inner city resembling San Francisco, and the sea gull’s cry overhead adds another dimension of charm.

Brandon stood in awe as the futuristic monorail whizzed by above, past red-brick buildings that had to be a century old.

An elderly man reclined on a park bench, occasionally tossing pieces of popcorn to a motley group of strutting pigeons. Behind him towered the Space Needle, yet another spectacular reminder of the World’s Fair — hosted by the city a million years ago.

For a price you can tour underground Seattle, a portion of the city buried ten yards beneath the present sidewalks and stores where merchants carried on trade at the turn of the century.

Along the sidewalks, I eavesdropped on passing conversations. People were discussing everything from politics to sex to groceries. Surprisingly, there is not the feeling of being swallowed by a callous, noisy man-made monster.

People are actually talking to each other.

The woman I Just passed smiled. There’s a middle-aged man who acknowledged we’re alive with a nod of his head.

Brandon interrupted to remind us he’d never ridden a bus and there’s one hissing to a stop just ahead. Piling on, I offered to pay but the driver said bus transportation downtown is free.

In the seats beside and behind us conversations continue.

“Oh my,” says one woman, “I hope I can find the purse I want. I’ve looked in ten stores and still can’t find the one.” “Honey,” offers her companion, “your problem is you’re just too picky, that’s all…”

Out the window I’m studying the endless variety of faces on the concrete walkways. I’ve always been one who enjoyed just watching people be human, never realizing what a great spot a bus seat is for doing just that…especially a free one.

Through the spotted glass I can see an attractive woman in a silk dress, followed by an unshaven man in a drunken stupor, three teenagers passing a brown sliver back and forth, a grocer sweeping the sidewalk in front of his store, a blind man tapping his way through the crowd.

Ahead is a policeman issuing directions to a pedestrian. A forefinger is hoisted into the air and he gestures wildly.

Another block glides by. There is a man sitting on a garbage can staring blankly ahead. Another stands beside a wall with his hat in his hand looking almost embarrassed.

The bus stops again and Brandon spies the monorail station. Kathy grins and we hop off.

Tickets are only 15 cents. For three nickels the glass-enclosed wonder whisks you about ten blocks to the Space Needle and several surrounding acres that contain a carnival, an enormous international shopping bazaar and a gymnasium-sized, fast food restaurant containing cafe booths from more than ten countries.

Adrenalin flowing, the hairs on our necks bristling, we closed our eyes and tried a Mongolian lunch that turned out to be better than edible. I never did ask what was in it.

Brandon, also daring in his own way, experimented with a hot dog and mustard.

The ocean provides a parking lot for the large freighters and tankers that routinely glide into their assigned piers along the Seattle docks.

From the top of the Needle, we watched one laden ship maneuver into her appointed place and shudder a breath of relief as mooring lines were tossed overboard.

But the oceanside setting gives more to the city than a simple berthing for weary ships. From a cordoned-off brick-lined shopping area called Pioneer Square, we walked four blocks to the harbor. There, the smell of city is overwhelmed by the aroma of sea.

A deep breath through the nostrils here sends images of crashing waves, boiling seafood and large diesel ships to the brain.

People are lined at dozens of small stands awaiting their turn at a shrimp or crab cocktail.

There’s also a covered market stretching for several blocks where we saw everything from hand-sized mushrooms to fresh octopus. A market manager named Joe stopped to talk for a few minutes. He had been in the same place for 20 years and said he occasionally enjoyed coming out from behind the counter to meet people.

Joe wanted to sell us half a tuna fish, but I explained how difficult it would be to shove the leg-sized denizen into the Lady K’s refrigerator.

He switched to touting his fresh salmon.

I also met a city fireman named Henry who was rummaging through a mountain of apples. In the course of our conversation, he said about one-fifth of the Seattle residents have completed a free, public course in emergency first aid treatment for heart attacks.

He also explained how Seattle is equipped to get to any heart attack victim in the city within five minutes after being notified by use of well-equipped and strategically located trucks.

“The city has emergency vans designed to provide vital treatment to heart patients before they reach the hospital. There’s really not another setup like it in the country.”

“If you were to drop over with a heart attack right now,” he continued, “chances are there would be a trained citizen to you within less than a minute, applying the necessary steps to keep you alive. That’s how well this program has been accepted in a city of half a million.”

Henry had been a fireman 12 years. He said he always came to the market on his days off. “I like to get fresh fruits and seafood and I like the atmosphere down here.”

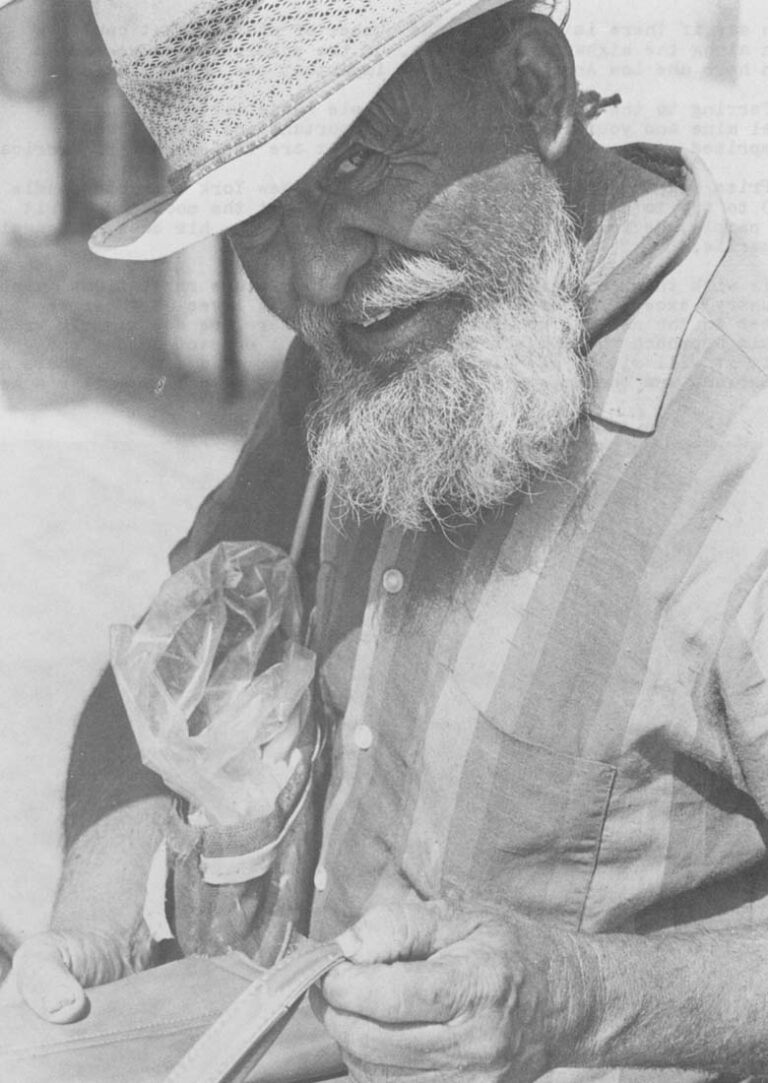

Later, we watched an elderly man named Thomas Lommori reel in a sizeable ocean perch from the edge of a pier. Brandon stood over the fish with three or four others while Thomas beamed over his catch.

“Must weigh two pounds,” I offered. “Nope,” he responded with a wink, “I’ll bet it’s nearly three young fella.”

Hauling up his metal stringer, he displayed several other nice-sized fish.

“Do you eat those?”

He looked at me as though I’d asked a silly question. “Of course I eat them. I take them home and put them in my ice box and eat them every one. Saves on my grocery bill.”

The 79-year-old widower re-baited his vintage model rod and reel with a pink hunk of raw shrimp, then sat on the dock to await another tug on the line.

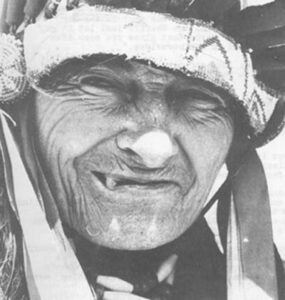

He said he came to the same spot on the days it wasn’t raining. “I call this my happy spot,” he said, “because it always gives me such happiness.”

We talked for ten minutes about his life. His wife had died of a stroke six years earlier and he lived alone in a small room near downtown.

Fishing gave him the greatest enjoyment from life other than having admirers around to ogle his catches.

He invited me to come back and sit with him the next day, but I explained how we had to be making ready to visit the highways once again.

A hundred wrinkles began at the edges of his faded eyes and raced down his cheek to a point beneath his chin when he smiled. “I’ll be thinkin’ about ya,” he said with a grin. “Wish me luck and I’ll do the same.”

I did just that and it must have worked too, for as we were walking back to the car, I glanced over my shoulder to see him struggling with another fish, even larger than the last.

I found it difficult to put my finger on what made the Seattle-Tacoma area noticeably different than other metropolitan areas we’ve seen. It was most likely the combination of scenic beauty, hospitable people and the ocean. Of these, the most important quality was the people and an apparent concern for their fellow man that was obvious to strangers.

Seattle taught me that hundreds of thousands of people can live together in a contained area and be relatively content…even with all the social ills that go hand-in-hand with such conglomerations.

TILLAMOOK, Ore. — Leaving Seattle, we had began the lengthy trek down the Pacific seaboard on Hwy. 101, not expecting a coastline that pulled us to it like a magnet.

From our first view of the massive shoreline rocks and expanse of unspoiled beaches, we were anxious to kick off shoes and run in the sand.

The state of Oregon accommodated by providing a parking space just large enough for the Lady K.

Brandon won the shoving and clothes-changing match to emerge first and race wildly into the breaking surf.

One disadvantage I can see to being six years old is an attention span limited to three minutes or less. Brandon couldn’t decide whether he wanted to splash in the water, build a sand castle, hunt sea shells or chase sea gulls, so he sat and stared at the waves.

Farther down the beach there was a furry mass that had apparently washed ashore with the tide. Growing closer, we could tell it was a sea lion.

Weighing at least 350 pounds, the large animal’s soft brown eyes had fixed in death, but its body remained warm to the touch. Blood still oozed from tiny puncture holes in its chest and eye. “Who shot him dad?” Brandon looked toward me for an answer. His eyes were squinted with concern and sadness.

I felt anger welling inside as I watched the persistent waves roll over the creature then pull back to leave it slightly deeper in the sand each time.

I told him I didn’t know who killed it, or why.

“But dad,” Brandon persisted, “he’s so cute. Why would anyone shoot him with a gun?”

I wished I could have answered his questions and relayed them to whoever investigates such target practice.

It appeared as though boredom and a lack of common sense had led someone to prove their prowess with a trigger and this was what they had to brag about.

Tears came to Brandon’s eyes as he stood there watching the fresh carcass bleed into the sand. I looked around the beach, but there was no one else in sight.

We turned and walked away. The urge to romp and run had been quelled by our discovery.

After we had stopped for the night near Tillamook, a friendly fellow named Eric Wines walked to the coach and introduced himself.

He asked if we’d ever been clam digging and I said no…in Arkansas the digging sport is generally limited to earthworms.

Eric said people had been finding a lot of clams on the beach just north of Tillamook and he offered three shovels if we wanted to give it a try. “The secret,” he explained, “is in watching for a small squirt coming from the sand. When you see it, run over and dig on the ocean side as deep as the shovel will go.”

Since the sport required no license and seemed easy, we wolfed down some fast food chicken and headed for the beach, 12 miles north of the Lady K.

The sun was near the water line when we arrived and following a torturous downhill hike through a blackberry patch and mud, we arrived panting on the rocky beach.

Another tip Eric had passed along was to dig wherever you spy a small hole in the sand. The rampaging Mastersons wasted little time in beginning excavation of every round opening on the beach.

I was about 100 yards from Kathy when I heard her yell.

It wasn’t one of those reserved shouts, rather it was the kind of scream you often hear when someone steps on a snake or a spider is found in bed.

“I’ve got one…I have got one of those little devils!” she bellowed. A man in his boat about 300 yards offshore stopped fishing to look. Brandon dropped his labor and went running. Afterall, this was our very first captured clam and he wasn’t about to be left out of the ceremony.

Maybe I should back up a moment to explain that Kathy has always delighted in beating her husband at any sport, whether it be the largest fish, the first fish, a hand of blackjack or finishing dinner first. This was indeed her moment of glory.

This was the first clam.

Her shouting ended as suddenly as it had started. Her head was down, apparently relishing the discovery in contented silence.

“Let us see.” I had reached her side, in near exhaustion from the sprint.

She hesitated, holding the clam tight in her fist. “Well, let me see it,” I persisted.

“It’s a rock,” she said softly.

After two hours, our tally was three thumbnail-sized clams and four smooth rocks.

Returning to the Lady K. we went to bed.

The next morning, Eric introduced me to a man named Pete Walker who lived in a mobile home across the highway.

Pete had been one of the long time loggers in Oregon and was as colorful a person as there was in those parts.

A dingy baseball cap sat cocked on his balding head and his dungaree shirt was open at the collar. He was eager to talk about logging and his life.

“Hee, hee,” he said. “It’s darn hard to find anyone nowadays who wants to listen to an old man. Most everyone is in too big a hurry.”

He said he lived in a log cabin deep in the Northwest woods until ten years ago when he retired from logging and moved to his house across from the RV park.

He was doing his weekly wash in the campground laundromat when we talked.

Pete told of a family who had grown up falling the towering, bark-covered cylinders, of losing a finger in the process and of a son who was 46 when a logging accident claimed his life.

His wife had died two years earlier and he coughed a lot when he spoke of her.

“Actually, there ain’t need for loggers like I was no more. The equipment they have now can do the work of ten like me. A lot of men I worked with are dead now. Only a few of us still hanging around.”

He recalled those past friends with me, a hearty, hefty lot who measured success by how many trees a man could fell and how good his word was.

As with so many others I’ve asked, Pete was quick to voice apprehension and concern over Americas’ future.

“This is as bad as I’ve seen in the country. No one seems to know what they’re doing. By darn, they say oil is going to start running out in 30 years, not to mention all this hanky panky going on in government. I’m worried, I don’t mind tellin’ ya one bit. My friends are too.”

To occupy his time, Pete has taken to studying birds of the Northwest and says he can give facts and figures on every species in the area. “I got lots of time to read and I do a lot of it,” he said. “It’s my hobby. I am also reading about the history of this area.”

I asked about the angry red lumps on the knuckle joints of each finger. He held one hand up for inspection.

“Arthritis,” he said. “I’ve got it real bad in my hands. Sometimes I can’t even move them it gets so bad. “Aspirin will help ease the hurting a little. I took three when I got up this morning.”

There had been a lot of rough times along with good in Pete’s 80 years of living and 55 years of marriage. But the high point, he said, was his 55th wedding anniversary only nine months before his wife, Eula, died. “They fooled us,” he said with a laugh. “By golly, the family acted like they’d forgotten and they took us to dinner where all our friends were waiting in the dark. It was one of the happiest times of our lives together. I was glad we got to share it before she died.”

After 90 minutes, Brandon burst through the door to say the Lady K was ready to roll. Pete was still reliving the past out loud when I left him at that laundry table. I was glad there had been some time to listen.

EUREKA, Calif. — I don’t believe anyone can successfully capture in writing or photography, the majesty of the giant redwood trees in northern California.

They possess a stately awe that even the most fertile of imaginations cannot adequately describe.

The tallest of the tall pine trees of northern Arkansas would stand like mere branches beside the bark-covered Goliaths. Even the 25-foot Lady K with our lifeboat in tow is only one-eighth as long as the tallest of these sequoias.

They imprinted a vision that will rest in my mind forever. I can close my eyes here, at the table of the Lady K, and visualize them reaching in a seemingly endless grope for the clouds.

We spent three days in the sanctity and hush of the redwood cathedrals to emerge rejuvenated and realigned for the continuation of a journey now more than 13,000 miles long.

The trees found in their natural state only in this section of California, possess qualities universally admired by all mankind…beauty, stature, respect and a mystery that lies in the roots of their beginnings as far back in geologic time as the Jurassic period.

Brandon could only shout “wow” while Kathy and I stood beneath the giants relishing the silence that is synonymous with the trees.

Their trunks, as large around as many living rooms, disappear into a three-inch deep carpet of pine needles that serves to reinforce the almost religious quiet where they live.

The subdued light of dawn remains just that until the sun overhead reaches the neon position and shafts of light can find their way straight down to the forest floor. As we sat at the base of one behemoth, the only sounds were these of birds chirping and the constant gurgle of a nearby creek.

It was total peace.

With the passage of the sun’s Zenith, a dusk-like shadow again returns to the forest, only an occasional beam of light finds its way through the maze.

The branches on the trees don’t even begin to sprout from the trunk until nearly 200 feet up. You feel the need to yield yourself to them. They weave an almost religious spell that makes one want to spend a lifetime at their feet.

I learned from a woman named Mary who lives near the groves, that tons of thousands of the trees have been felled by lumber companies in the area.

Her words were reinforced by the many log trucks we saw on the highway, each laden to great heights with bodies of slain redwoods.

But she also said there have been dozens of groves purchased and maintained by private clubs, organizations and individuals in order to preserve them from the ruthless profit seekers. Such groves are often named for these who perform the service.

As we left the sanctuary and drove southward from Eureka along Hwy. 101, we saw mills processing thousands of the redwoods. They were stacked eight and nine deep in rows hundreds of yards long beside the highway. It made us sad to see them stripped naked and awaiting an ultimate unholy dismemberment by the axe man’s screeching buzz saw.

Petaluma, Calif. — Kathy saw it first in the distance. It was like an endless white sheet stretched on poles alongside the highway.

For as far as the eye could see, the flopping white cloth rode the curves and inclines of the barren hills of northern California’s wine country.

And it did not stop. Finally, I pulled the Lady K alongside the highway and we stared at the fence. “A wind breaker?” I suggested. “Yep, it must be some kind of cloth fence to break the wind…”

Kathy looked at me with one of those…I don’t believe you…looks and nodded.

It wasn’t until we anchored for the night at the Petaluma KOA campground that we discovered the mysterious rambling divider was actually a reputed piece of art work called Christo’s fence.

It seems a Bulgarian named Christo Javacheff had spent $2 million and three years to erect the nylon and steel fence that spanned 24 miles. But it was only to be up for two weeks.

We had stumbled across the masterpiece only four days before it was to be uprooted.

I couldn’t find Christo. Most people said he made himself intentionally unavailable to journalist types anyway.

No one seemed to know why a person would fight three years of legal battles, spend $2 million and hire 300 workmen to erect such a piece of artwork in a giant cow pasture.

A woman named Ann summed up the majority feeling of those I spoke with. “I can’t imagine anyone spending that kind of money on such a silly project. Look how many people $2 million could help. Frankly, I didn’t need to drive the 24-mile trip to stare at it. One glance was plenty. Afterall, if you’ve seen one sheet flapping in the breeze, you’ve seen them all.”

I have to confess I was somewhat taken with the novelty of Christo’s idea and the drive along the back roads of Sonoma County to follow the fence to its termination in the ocean was enjoyable.

As to the art value of an 18-foot-high wall of nylon, I had to agree with Ann.

A few of the dairy farmers whose lands Christo’s fence crossed were having a field day when we drove by. One enterprising family was selling barbecued chicken in their front yard while another enthusiast of free enterprise peddled cold drinks to the lookers.

Most farmers involved had at first opposed the fence across their lands, but one told me that after Christo agreed to give them the materials from the fence when the showing ended, the attitude changed radically.

“Diplomat” Christo was said to have even softened the irate tampers of the crustier farmers with television sets and other rewards for their understanding.

Where the slender, dark-haired drapist got his money for the fence seemed to be largely a secret. But then, Kathy reminded me, who ever knows where drape artists get their money?

Sonoma County, in addition to drapes is also known for the wine produced there.

Traveling into San Francisco, we passed vineyard after vineyard for as far as the eye could see. The terrain is more rugged than I had imagined around San Francisco and largely barren except for the chest-high green grape vines.

Before reaching the Golden Gate Bridge, we stopped at the Parducci Winery beside the highway and spent two hours learning about wine making from the head chemist, a rotund, jolly fellow named Joseph.

He took us to where men were emptying dump trucks filled with grapes into a metal bin. From there, they were crushed and sent to a machine that pulled all the stems and seeds out.

Kathy’s favorite part of that experience was the wine tasting room. We spent an hour there before easing back on the highway to head for San Quentin Prison.

Brandon couldn’t understand why we wanted to see a jail. I couldn’t either, except that I had long heard about California’s most infamous prison and I wanted to see for myself.

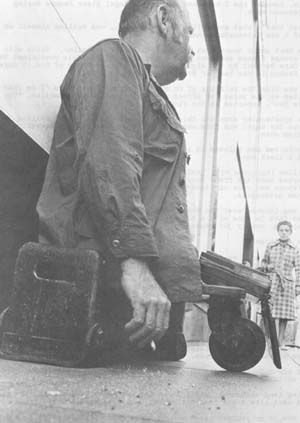

SAN FRANCISCO, Calif — I’m certain Jack had a last name, but he never said so and I didn’t ask.

While walking the sidewalks around Union Square downtown, I noticed his head at knee level in the crowd. Minus both legs, the middle-aged man rested his trunk on a make-shift, rolling plank.

A box of colored pencils was where his lap should have been and there were two wooden handles of sorts that allowed his arms to reach the ground and scoot his body along.

From a distance, I saw several stop and drop coins into the cigar box. Most didn’t bother taking a pencil. His mustachioed face turned from side to side, occasionally catching one of the curious, like myself, staring. I found myself wondering what life would be like without a set of legs. I questioned whether I’d be strong enough to endure.

It was such ponderings that finally prompted me to plop down on the sidewalk beside him and strike up a conversation. A friendly sort, Jack seemed to welcome my company.

Trying to make myself feel a bit more at ease, I dropped 50 cents into the box and took two pencils. He said thanks.

Jack, I discovered, was married and the father of three children. He had lost his legs in a farm accident more than 20 years ago and swears his mother’s prayers were the only thing that kept him from bleeding to death on that cold November morning. “I was unconscious through most of it.”

A welder by trade, Jack said he worked in the sign business for 23 years before ailing health forced him to quit.

“You bet I worked,” he said. “I don’t want anything for nothing, not ever. Why, I’m not even drawing government money. I haven’t even tried to get it.”

As he talked, I watched the faces of those passing by. Macy’s Department Store was only a block away and numbers of well-dressed women strolled passed. Some occasionally cast expressions of disgust in our direction.

About one in 50 stopped to leave coins with Jack. He always offered to sharpen the pencils, but no one took him up on it.

I also noticed how the passersby seemed to be more embarrassed by Jack’s missing legs than he was.

Several thought they were sneaking a peek sideways at him, then they’d often look back over their shoulders after walking by. Jack never acted like he noticed or cared, at least I don’t believe he did either one.

With my rump on the cold sidewalk, I could also see a little of how this person saw life. Even the shortest of the short were tall. Looking up to the entire world was not a comfortable feeling…it kept me on the defensive.

As candid a man as I have met, Jack related stories of past years on the streets of Los Angeles. “The cops there didn’t mess around with people like me on the streets,” he said. “I kicked back $15 a week to the cops on my street or I got the heck beat out of me. That was quite a few years back.”

He told of one evening when two policemen allegedly gathered him off the sidewalk and took him to a dark place. “They almost beat me to death,” he said. “They didn’t fool around, I’m telling ya. Anyone selling anything on the streets had to take care of the cops or else.”

He said the police in San Francisco weren’t as harsh, at least not nowadays. “Oh, I know what goes on these streets. I’m here everyday. See that peddler over there, the one selling jewelry,” he motioned toward a man with a makeshift stand set up on the opposite sidewalk.

“Well, according to this newspaper map in my pocket, he’s not supposed to be in this area. How do you suppose he gets away with it?” he smiled and winked. “Hear that band playing around the corner?” I listened and could hear the sounds of rock music floating through the concrete canyon. “They’re not supposed to be here either. There’s a noise ordinance prohibiting it. How do you suppose they’re down here doing that?” Again he winked.

I wondered how he gets to and from his house. He said he drives a car by using special attachments. “You can do anything when you have to mister. Anything. It helps to be tough as a boot, though.”

Curious to know more about life along the streets in San Francisco, I asked Jack to continue. He took a lengthy drag from his filter-tipped cigarette and heaved a dramatic sigh.

“You’ve heard it compared to a jungle, right? Well, that’s what it is. I’ve seen men shot down on these streets. I’ve been robbed at gun point and knifepoint and I’ve had to fight off guys with weird intentions. You’ve got to be tough, that’s all. There’s a lot of psychos out here and a lot of addicts who are slimier than an eel in a snot can. The addicts need money and someone that looks like me is a heck of a target.”

He said he lost his legs when he was only a teenager, but I noticed his green fatigue army shirt and started to ask if he was wearing it to make people think he might have lost his legs in the military.

But I didn’t ask. I knew the answer and didn’t see any need in making him say it. No matter how he lost them, they were gone.

If there was one thing Jack didn’t want in any shape or form it was pity. He had spent a lifetime doing for himself and being strong enough to survive in a world twice his size. “I come out here three or four times a week and generally make $8 to $10 a time,” he said. “Plus I’ve got some savings and pension to rely on.”

A man interrupted his thoughts to leave 50 cents. He then grabbed Jack’s hand and shook it gently. Another stopped and left a quarter.

It was nearing 5 p.m. and the sidewalks would soon be filled to the brim with a working middle class heading for home.

He said this was usually his best time of the day.

It was beneficial experience for me to spend an hour alongside Jack, to absorb the stares of the more fortunate, to see how life could be for me or anyone else should fate decree so.

How I wished those bearing sour expressions could have sat there beside us for a while.

Oakland, Calif. — In the community of Alameda Across the murky Oakland Bay from where Jack sells his pencils, floats a few acres of asphalt and bricks known as Government Island.

Only a hundred yards from the mainland and within sight of the Oakland Bay and Golden Gate Bridges, this island has for ten years reserved a special place in the “best forgotten” section of my mind.

Government Island is the U.S. Coast Guard boot camp…ten weeks of mental and physical agony, a nightmare that recurred for months after I graduated with Company Echo 57 in 1967.

The memories rushed back as Kathy, Brandon and I drove across the narrow inlet bridge and approached the guard station…what was that young boy’s name? The one whose head was shoved against the concrete curb by a drill instructor, and who died from the blow?

What was that large black recruit’s name? The one who was forced to stand in a cold rain all morning and sing “We Shall Overcome” at the top of his voice because he had been humming.

Who were those three in my Company who tried to swim for it in the second week rather than endure the torture and harassment?

They have all left those weeks behind, replaced by a new group of faces and bodies, but they’re not forgotten, at least not by me.

There was irony in the fact that in the afternoon we went to Government Island, a group of workmen were tearing down the wooden recruit barracks where I spent more than two months.

There are now modern, concrete living quarters at the far end of the island, on the exact spot where drill instructors screamed curse words and assorted foul language in our faces striving toward their assigned goals of reducing our individualities to rubble.

I stood again on the spot where one drill instructor made me do 500 push-up’s for a mistake. It was the same place the new arrivals had stood at attention in the rain for 90 minutes during the night we climbed off the bus on Government Island.

Creeping up the partially-destroyed stairs to where the second floor barracks stood, I looked around at what were once the four walls. There, in the middle, was where I anxiously counted away 70 nights of my life. Across the room was where another recruit…a friend, an intelligent, likable guy, wet his bed on purpose to escape the hall with a discharge.

En route across the manicured island to headquarters office, I stopped a nervous recruit to ask how things were nowadays. He snapped to attention and said better. But what did he have to compare with?

The white hats that had to be scrubbed daily are gone, replaced by navy blue baseball caps. The white leggings have also vanished, pants legs now fall free.

I did see several D.I.’s screaming in the faces of rigid recruits. But the atmosphere seemed different…more relaxed.

At the office I asked to see records from Echo 57. A polite young fellow made several phone calls but finally said they didn’t keep back records past 1970. In short, we never existed on Government Island.

When we left the red-brick building and climbed into the car, I found it difficult to believe the only records remaining of those years are in the minds of those who experienced it.

Artichoke fields of northern California, near Castroville, Calif.

LOS ANGELES, Calif. — Two blocks from where we attached the Lady K in Anaheim, Brandon and I happened across the Angel Elder Nesure during an afternoon walk.

At least that’s what evangelist Oscar Lane Jr., was calling himself on the side of a new International Harvester truck.

It was that shiny truck that first captured our attention. White with giant orange flames emblazon across the side, his vehicle proclaimed the “Last Days Revival by the Highly Anointed Renowned Man of God… Angel Elder Nesure in the body of Evangelist Oscar Lane Jr.”

There was also the painting of an open Bible with the words “I Am That I Am” inscribed on the pages for effect and still another proclamation, “The Time Is Now”, inserted in the flames.

What a spectacular show was this truck in itself. I felt a calling to seek out the angel and find out more about Brother Oscar’s traveling salvation show.

A gray-haired man pointed us in the direction of a new Airstream trailer parked a block away.

A Cadillac limousine with velvet burgundy interior and stereo headphones was parked near the front door. On the other side of the mobile home sat a miniature red race car that caught Brandon’s eye. It was parked next to a new motorcycle.

Water was leaping over the top of the silver trailer and I walked around to come face to face with a black man who stood six-foot, six-inches tall and weighed nearly 300 pounds.

It was the angel.

Introducing myself as an interested bystander, I struck up a discussion about the business of saving lost souls.

At first he was somewhat reluctant to talk about much of anything. He chose instead to grunt a lot and continue scrubbing the silver trailer with the vigor of a fire and brimstone evangelist trying to convince the sinner that time for salvation was running short.

But I continued to talk and ask questions about he and his family until he became a bit better conversationalist.

Oscar said he began his life as a nomadic revivalist when he was a child. His father is still a minister in Beaumont, Texas, and his four brothers are now all men of the cloth.

He met his wife, Lula, during a revival in the south and they now have three children.

Sporting long sideburns, white shoes and pastel-colored slacks, the angel looked more like a pro football player than a convicted Christian.

“Well now, in my younger years around Louisville, Kentucky, I did do some boxing. As a matter of fact, I was close friends with Ali and even boxed with him there at the gym. I knew him when he was just a kid.”

At 34, Oscar said he enjoys the life of a gypsy, as do his children and Lula. “We’ve been in a lot of foreign countries and we’re going to Africa in a few months. This in the best education our kids could get.”

That remark led to an inevitable question about their children’s education. “They study several hours a day by correspondence,” he said quickly. “And it’s an awful lot better than being in a public school somewhere.”

“I don’t know about where you come from, but in Texas drugs are running wild even in grade school. My kids are much better off learning in their home, with their parents.”

Brandon asked if he could sit in the small race car and the angel nodded. “It goes 55,” he said. “I had it custom made for my oldest son. He’s 10.” I smiled and watched Brandon’s eyes grow wide as he climbed inside the cockpit.

“Tell me about your ministry…about your revivals.”

“Well, not much to tell,” he said. “We go from town to town and I conduct my revivals. There’s not really a set schedule. My business manager handles the scheduling and most of the financial end.”

“But what is your message? What do you say to those who come?”

“I mainly preach an the Bible and the Commandments. I tell them a person can’t follow a small part of what the Bible says without following all of it to the letter. You don’t just take a bite out of a sandwich unless you eat the whole thing.”

While I was busy trying to relate an egg salad sandwich to the Bible, Angel Nesure continued. “Now I’ve had people try to relate me to those evangelists who are in the business purely for the profit…you know the kind I mean, a man who starts out small and works his way up to the big time, then forgets where he came from.”

“Where he came from, I’m telling you, was the people, the common, everyday people and God himself who put him up there and they can bring him down just as easy.”

“But I’m not like that, no sir. I’m not ever going to forget where I came from, no matter how big I get. For instance, I’m going to got a jet here pretty soon but do you think that’s going to my head, no sir…not for a minute.”

I asked his opinion of race relations in America today and where the nation seems to be headed from that angle.

Rinsing the soap from his chrome bumper, he pondered a moment. “Well, I think things are getting better in that area, but the churches aren’t doing enough to help.”

“There should be more understanding preached on that subject. The churches are failing and there’s still a lot of bigotry preached in the homes by parents.”

Since all angels I’ve ever known have also been better than average prophets, I asked this one about the November elections. “God told me Gerald Ford will not be the next President,” he said while squeezing suds from a sponge through fingers the size of hot dogs.

Curious about his entry into the world of traveling road shows, I asked if he had always been convinced of his calling. “I became convinced of miracles when God healed me from bone cancer when I was a teenager,” he said. “I had people praying day and night for me and it just went away. It was a miracle, a plain and simple miracle from Heaven.”

He hoisted his pants leg to display a two-inch scar on his shin. “It was there,” he said pointing to the mark, “and all those prayers drove it away.”

A new deep-red Lincoln Mark IV with a moon roof parked behind the trailer caught my eye.

I asked if it, too, was his. He nodded.

“With so many vehicles, how do you drive them all from place to place?” I could tell from his expression my endless stream of questions were beginning to test his anointment.

“Well, I drive one car and my wife drives another and either the business manager or my man whose hired to do the moving and setting up drives the truck. The motorcycle and race car go in the back of the truck.”

He said they were leaving Los Angeles the next morning so I wouldn’t be able to experience his revival. Their next stop was Oakland and they would stay as long as the crowds were good.

Each evening session lasted about two hours and the angel was a bit unclear when I asked if he repeated the same sermons in different towns. He did say he had a favorite or two.

I wished I could have watched Angel Nesure Elder…in the form of Evangelist Oscar Lane Jr., pound the pulpit and earn his living. But then maybe it was better that Brandon and I bade them farewell when we did.

Afterall, I could just imagine myself prostrate in the sawdust, crawling toward Oscar with trusting arms outstretched, helping to make payments on the Cadillac and Lincoln to insure my ultimate deliverance.

When Brandon and I returned to the Lady K, I related the story of Angel Elder to Kathy and we pored over one family Bible and two borrowed concordances in search of an angel named Elder Nesure.

Would you believe…we couldn’t find even a mention of that winged rascal.

One thing is an ultimate truth, however, tonight out there somewhere in America Evangelist Oscar Lane Jr., “The Highly Anointed Man of God” is trying out the wings on his new jet, planning his trip to Africa and doubtlessly remembering from whence he came.

San Diego, Calif. — One of the most difficult tasks in writing about a year-long odyssey across America is agonizing over which experiences have to be discarded.

In a week’s time, we pass through many communities and meet and talk with large numbers of people from every walk of life, most of whom have interesting personal stories and philosophies to relate.

This doesn’t include the countless points of interest and fact likely to capture the imaginations of those following our journey from their armchairs.

There are as many ways to approach this project as there are people who would enjoy doing it. For instance, I’ve been advised to concentrate on only a few topics and delve at depth into those… “don’t be so broad.”

Others have suggested that a lot of time and space should not be devoted to only one aspect or personality in an infinite sea of possibilities…”give us a varied look at many people and places.”

In an attempt to illustrate this unwieldy situation, I spent two days driving and studying the possibilities for legitimate stories along one small stretch of freeway from Los Angeles to San Diego, a distance of less than 100 miles.

Pulling onto the Santa Anna Freeway, longest in the western United States, the three of us aimed our noses southward and filed into the flow of traffic.

In only a few minutes we were passing through Newport Beach where John Wayne docks his yacht, a converted 150-foot U.S. Navy minesweeper.

There, on the right, is El Toro Marine Base, where many of the lighter-than-air blimps were once based in the auditorium-sized hangers. The explosion scene for the movie Hindenburg was filmed there. The area now houses one of the country’s largest helicopter bases.

A sudden gust rocks our tiny car. Winds known as the Santana often sweep across this section of California from the adjacent desert bringing gusts of from 80 to 90 miles an hour. Those gum trees planted like fences along the roadway help to block some of Santana’s force.

There are also other shrubs rooted beside the highway. Most people zip by without ever noticing them. The plant is called pig face and those who live along the roaring thoroughfare plant the stuff to absorb about 40 percent of the freeway noise.

To the immediate left are the beginnings of orange groves. A man named William Wolfskill introduced the first dimpled ovals that now cover thousands of acres in the state. A good story here lies in the recent removal of smoking smudge pots from the groves because of pollution problems and their replacement by propellers.

The revolving metal blades are mounted in towers throughout the orchards. They keep warm air circulating above the crop preventing frostbite.

Also on the left, we’re now passing the largest drag strip in California where anyone so inclined can come on weeknights and race his car against anyone else for $3…another slice of Americana.

Another section of El Toro base comes into view to the left. This is the airstrip where Air Force One landed when former President Nixon flew to his San Clemente retreat. A helicopter would bounce him from this base to the estate a few miles farther down the freeway.

Cresting the hill at right is a relatively-new tourist attraction called Lion Country Safari, not particularly newsworthy except that the famous swallows of Capistrano are beginning to flock here each year instead of to the historical mission a few miles south.

It seems they prefer the more modern accommodations of the bird sanctuary at Lion Country. Incidentally, I also discovered this is where Frazer, the lion who did all the roaring at the beginning of all the old MGM movies, lived until he reached 110. His death sparked banner headlines and even parades in the county.

More miles pass and on the right, sprawled across several hillsides, we can see the Leisure World Community, a Spanish-styled self-contained city where only those 55 and older whose incomes equal at least three times the monthly payments on their homes can live.

The residents have their own fire and medical protection, recreational facilities and a rambling shopping center. The homes cost between $600 and $1,000 monthly.

An interesting point about Leisure World Community and the lifestyle of those therein, is that we are seeing more and more neighborhoods of the suburbs turning to the self-contained concept. In Los Angeles there are dozens of neighborhoods that have formed their own police, fire and recreation services and support them through regular monthly fees from the residents.

If the trend toward leaving the inner cities to wither and die continues, this could well be a way of life in future America. Instead of living in small towns, people will confine their associations, recreation and basic concerns to the immediate neighborhood-community.

We’ve now traveled through five distinct cities and haven’t been able to determine where one ended and the other began.

To the right is the town of Mission Viejo, a small place to by-passers, but also the site of Casey Tibb’s Dude Ranch where President Ford’s son, Steve, lives and works. It’s also the home of Christine Jorgenson, one of the original sex change people and two 1976 Olympic Gold Medal winners, Nancy Babashov and Brian Goddell. We could spend two weeks right here.

The trip continuing, we are surrounded by an expanse of land known as the Irvine Ranch. There was once a cattleman named Irvine who made friends with the Spanish.

In fact, he became such close friends, they said they’d give him all the land he could cover in a day’s horseback ride south. The land grant would extend laterally from the ocean to the Saddleback Mountains on the east.

Well, Irvine mounted his steed and before the sun had set he owned 98,000 acres. The ranch has been the site for many a movie, including “All Quiet on the Western Front.” It’s also where a scientist first measured the speed of light in a tunnel constructed on the rangeland.

The city limits sign of San Juan Capistrano just passed by. It’s a sleepy little village where city ordinance requires every structure to have a red-tile roof.

There are bells hanging everywhere, even in gas stations and restaurants.

On March 19 each year the swallows that haven’t changed reservations to Lion Country return to greet the media and spectators at the mission. Couples can still marry in the ancient mission, but I was told there’s a two-year waiting list.

I also learned there are 21 original missions in California, each situated a day’s donkey ride apart.

The attractive public school building in San Juan Capistrano now stands abandoned. It was closed by governmental order, as were other school buildings of two stories or more, after a serious earthquake in 1971.

Several blocks away is the San Juan Hills Country Club where Richard Nixon still plays golf once or twice a week under the watchful eye of Secret Service agents. Those agents reportedly selected the course because of excellent vantage points.

Back on the freeway we pass a place known as Smugglers’ Cove where illegal alcohol was slipped into California by boats during prohibition. It’s also the spot referred to as Dana’s Point in the novel, “Two Years Before the Mast.”

Entering San Clemente, the southernmost city in Orange County, I learn how the small town’s police force swelled from seven to more than 100 when Nixon was President and I also discover that property values have tripled since he’s lived there.

Curious about how Nixon acquired the San Clemente estate, I was told by a knowledgeable man that Robert Abplanalp, the fellow who patented the aerosol spray valve, owned 21 acres of beachfront property. He reportedly sold the acreage to Nixon who kept the ranch and four acres then sold the other 17 acres back.

On a hill about a mile from the estate sits the San Clemente Inn, a former home away from home for the Secret Service and the Nixon entourage when the former President was there.

I was told if you happened to be a guest in the hotel when Nixon came, they simply moved you out to wherever else you wanted to stay…at taxpayers’ expense.

The enclosed and tree-shrouded Nixon compound is right next door to James Arness’ horse ranch. You can’t see the house from the road and a guard sees to it that no one gets a closer view than the edge of the road.

To me, it resembled a prison.

Nixon once spent quite a lot of time strolling the beach behind the estate. But he gave that up, for the most part, when beach watchers began cursing him and making obscene gestures.

With a U. S. Coast Guard station on the left and Matt Dillon on the right, I couldn’t see that Nixon had much to fear.

On we drove, past more potential stories. The San Onofre Nuclear Power Plants under construction where it is said a quantity of plutonium is unaccounted for, an interior check point for illegal aliens, there are reportedly one million in California alone.

Camp Pendleton Marine Base, the second largest in the country, is on the left. Here the Marines are experimenting with the removal of salt from water through the use of ordinary tomatoes. There are acres and acres of tomato plants beside the freeway.

To the right are white and green barracks where the Gomer Pyle television show was filmed. We’re now in the town of Oceanside, where the most exciting days of the month are the first and 15th when the eagle flies on the base.

More miles pass. On the hills to the left in Ensenitas, are thousands of acres of flowers. This is where most of the nation’s flower seeds originate. The plants are grown to certain size then harvested for seed. Examine the next package of flower seeds you buy and see if Ensenitas or Locodia is written on the back.

Again on the left, barely visible, is the well-publicized La Costa Country Club, one of the last places Jimmy Hoffa was seen alive and alleged by a Los Angeles newspaper to have connections to organized crime.

We’re into Del Mar and on the right is the Del Mar Race Track. High on a hill above the track I can see the homes of James Garner, Phyllis Diller, George Peppard and Burl Ives, all of whom own and race thoroughbred horses.

Entering the outskirts of San Diego, we encounter a unique industrial park, the product of learning from the mistakes of similar areas in Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Here the 400 major industries of the state’s third largest city are centralized outside the city limits in an area noted for strong breezes. Commuter buses carry employees to and from the park each day.

Also on the right is the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, a place frequented by Jacques Cousteau and Dr. Jonas Salk.

Then comes the spectacular, man-made Mission Bay, dredged at a cost of millions but not charged to taxpayers. Rent from occupants of a mobile home park located on an island in the bay makes the annual payment on the project.

Over there, in the distance, is a beige-colored, oval building with the words Ryan Corporation on the side. This is where Lindburg’s plane, The Spirit of St. Louis, was built. Also within sight is the Federal Correctional Institution where Lynette Squeaky Fromme and Patty Hearst were kept.

Another mile passes and we can see the Coronado Bridge, one of three in the world that makes a 90 degree turn in the middle of the span.

There are a number of stories we’ve passed that I’ve neglected to mention, like the Chicano paintings beneath the overpasses which were commissioned by the city. There was also Torry Pines a few miles back. It’s a state park where hand gliding is king. Then there is the San Diego Airport we passed five minutes ago. Pilots who fly in there have voted it the third worst to land at because they have to come in directly over homes and a crowded freeways with a tight landing pattern.

Who can say if there is an end to the number of stories that could be written along the highways of America. Of the possibilities we passed between here and Los Angeles, the most important was never mentioned.

I’m referring to the common, everyday people whose lives in many ways parallel mine and yours. Their voice is important and their lives are comprised of experiences and lessons that are the essence of America.

Nobel Prize winner John Steinbeck set out from New York with his poodle in 1960 to try to discover our nation and document the mood and spirit of its people. He failed and admitted the failure in his book, “Travels with Charlie.”

So it is with this journalist. I am failing to capture revelations about the country, except for detailing the thoughts and lives of those we encounter in the natural course of this trip. There are doubtlessly writers who would approach the project differently. But I suspect anyone who attempts it will sit before his or her typewriter in confusion. There are many Americas and the emphasis of each writer lies with that writer’s heart.

It’s the people who comprise a nation more so than the fruits of their labor or the natural wonders. For we have seen them laughing, crying, fighting, loving, controlling banks and rummaging through garbage can, from resorts in the East to the Mohave Desert. And when this year has ended, it is these smiles, worries and expressions we will treasure.

©1976 Mike Masterson

Mike Masterson is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Sentinel Record (Hot Springs, Arkansas). Mr. Masterson will travel throughout the U.S. with his family and write about the country and its people in 1976. This article may be published with credit to The Sentinel Record and to Mr. Masterson as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.