GRAND JUNCTION, COLO. — When I was in school, a skinny geography professor with thick dark glasses used to talk about an infatuation with this western Colorado town.

I could still hear him talking in a shrill voice about his fascination with the majesty of surrounding mountains and what a large number of services Grand Junction provided for such a small city.

As most folks might do, I fantasized what Grand Junction would look like and, like most fantasies, the vision was unreal.

Rumbling into the city of 20,200 from the west on Hwy. 50, we rolled past flat, mostly barren landscape.

Grand Junction was nestled at the foot of a mountain pass, spread like a checkered table cloth across the brown flatlands.

The KOA campground was close to the mountains on the other side of town and, after bedding down the Lady K, we made our way back into the city.

The people we met in Grand Junction were all smiling and friendly. Downtown merchants had long ago converted their stores into an open walking mall and some of the older stores had new faces and interiors.

That skinny teacher had been right. There were more services here than in many towns of three times the size we’d passed through. The reason, I discovered from Fred, a local hardware store owner, was that it was the only substantial town for three hours in any direction.

Formerly a bustling cow town, Grand Junction is now catering more to industry, tourism, and the thousands of outdoors folk who come each year in search of wild game in the wilderness of those adjoining mountains.

After a day, we made ready for our final approach into the passes through the Rocky Mountains, still 300 miles eastward.

The plan was to drive to Vail, Colorado that day, give Lady K a breather, then tackle the 10,600-foot Vail Pass and 12,000-foot Loveland Pass early the next morning.

Arriving on the western outskirts of Vail, a young man named David, who had come there from New Jersey three months earlier, told me the passes had been closed by snowfall two weeks earlier, and snow was predicted again the next day.

But I talked gently to the Lady K and she assured me she could make the grade if I filled her with a breakfast of 68.9 premium and let her stride in low gear, “without that blasted four-wheeled lifeboat tacked to my bumper.”

Vail is like no other place we’d seen in our journey.

It’s what the rest of the nation will doubtlessly resemble one day should we become a country of government building codes and restrictions.

The neat stores look almost alike, except for signs in front. All were built to copy Alpine chalets and the prices for almost everything were as high as the pointed roof arches.

The place looked almost as if Brandon had taken a toy set of miniature Swiss buildings and made a play town. The feeling we got from being in Vail can best be compared to that of being in Disneyland or Opryland or a military base. We were always wondering if we might be walking some place we shouldn’t or be in some spot that’s out of bounds.

Almost everyone we saw was under 30 years old. Whether they worked in the stores, cafes, gas stations or just walked the streets. Conversation usually revolved around skiing on the slopes or whispered prayers for an early snowfall.

Later, David told me Vail was, indeed, a town comprised largely of young ski buffs and party-lovers who just want to “be where the action is.” He said they come from all over the country, beg for jobs and work for minimum wages just to be there.

He’d been working at the campground and living with his wife in a tent for some time. “I’ve got my application in as a bartender, but I don’t know what’ll happen,” he said, brushing a handful of yellow strands from in front of his brown eyes.

“Until then, I guess I’ll just keep doing manual labor right here at the camp…”

We awoke early the next morning and roused the Lady K with the twist of a slender key. Shaking off an engine chill, I eased her in for the promised breakfast. A fellow named Steve in Grand Junction had told me to put premium in the tank for the steep uphill climb, claiming the carburetion would improve and the coach would run more smoothly.

The first climb began with a long grade just outside of Vail. We rose nearly 11,OOO feet and the crest of Vail Pass before dropping back into a valley along Hwy 70. Kathy and Brandon followed close behind in the Honda.

Later she told me Brandon was disappointed at not seeing John Denver sitting beneath an evergreen with guitar in hand.

“Well, Mommy, this iS Rocky Mountains High, isn’t it?”

The beauty of those snow-crested peaks was unparalleled. I could see why ballads about them were written. They were rugged like a towering oak in winter, yet gentle like the flow of an icicle after a snowstorm.

We pulled beside the highway before starting the second ascent to the 11,900-foot Loveland Pass and the Eisenhower Tunnel, A lake that stretched as far as the eye could see lay before us. It was surrounded by the overwhelming blue-green mountains.

We each stood staring in silence at their presence. The Rockies generated an inner peace…a tranquility like I’ve never felt. The air was cool and fresh. A breeze from the water whipped at our coats and in our hair. The only sounds were of birds singing and the occasional roar of a passing vehicle.

For that moment we were a part of the place where God would build his home if he were in the market for real estate.

The second climb was steeper but shorter.

Kathy stayed on the Lady K’s bumper and our portable home hummed like the base end of a harmonica to the mouth of that concrete tunnel and through the darkness to the other side without so much as a cough or complaint.

The final 60 miles into Denver were all downhill. Reattaching the Honda, the three of us settled back for the coast.

DENVER, COLO. — Like wooshing off a great sliding board, the Lady K slid from the 12,000-foot eastern crest of the Rocky Mountains into the vast expanse of the mile-high city.

An old friend who had lived in Denver for several years was warned of our impending arrival. But he was foolish enough to invite us to stay with him and his wife anyway.

I’ll call him Joe, since what I’m about to write might make him uncomfortable to read. His wife, we’ll name Sarah…a name as pretty as she is.

Sarah and Joe’s apartment was small, but comfortable. They had prepared their water bed in the guest room for Kathy and me, and Brandon was assigned the well-cushioned couch. Within an hour, we were reliving the past amid outrageous belly laughs and constant chatter.

On the surface, Joe hadn’t changed much. He still laughed down deep in his throat like the resounding boom of a kettle drum. He was somewhat heavier and smoked more than he used to.

I had always liked him mostly because of his carefree nature and an unequalled sense of humor.

Sarah, who did manual work in a factory for 60 or so hours a week, was portly and pretty, especially inside where it counts. She was the kind who seemed constantly concerned about another’s feelings, even at the expense of her own.

Joe hadn’t worked for several weeks after being laid off from a surveying job. He said he spent most days sleeping late, watching television, and just “taking it easy.”

He had held several odd jobs since I’d seen him last, including managing a pancake house, road surveying, and a manual labor job. He said he knew he was floating, but added that he wasn’t too concerned about rejoining the “eight to five crowd” especially since Sarah’s bringing in enough for us to get by on.”

We had joined the celebration of renewed acquaintances with several highballs, but Joe continued plunking in ice cubes and pouring until it was time to “get another bottle.” I rode with him to the liquor store where he asked if he could borrow some money until Sarah got home.

Driving back, he pointed at a car parked beside the street and revealed how he had once kicked the car’s door in after tipping one too many. He said he had gotten off the charges by defending himself in court. “The old lady who saw me do it lived a block away,” he said, “and I proved there was no way she could have seen me from her room at night…but she really did…he chuckled.

I smiled an obliging smile and shook my head.

We spent four days with Joe and Sarah. Each morning she’d leave for work before we got up and return exhausted after dark.

Since they had one car, Joe bypassed his usual chauffeuring of her to work each morning and we used our Honda to drive around Denver.

On the freeway, Joe pointed out the Bronco football stadium and a few other places around the downtown area. Denver was pretty in some places, but old and dirty in others.

There were many red-brick buildings and Joe made it a point to take us past the “vice section of town where you could get anything you want.”

After two days, we detected a festering infection of unhappiness between Joe and Sarah.

She said she resented him for not working. “I owned the apartment when we got married. He moved in with me and now he thinks he owns it,” she told Kathy one night. “He’s not even trying to find a job.”

“Sarah is really fat,” Joe said to me one afternoon between his drinks. “But she takes good care of me…”

The night before we left, Sarah didn’t get home until after nine.

She had called earlier in the afternoon to say a semi-truck had come in and she would be tied up until it was loaded. Kathy fixed dinner, while Joe drank himself into drowsiness.

We three were watching television about 9:30. Joe had gone upstairs and laid down on the bed. Sarah, wearing a soiled pants suit and an exhausted smile, came through the door. There was a rumbling from the bedroom.

Suddenly, Joe was downstairs screaming at the top of his voice. Sarah, whose face was covered with grime, dropped into a chair beside me.

“What do you mean being late for dinner?” Joe roared. “You missed a good dinner and, since you can’t be on time, by God, you get nothing to eat tonight, do you understand? Nothing…”

Kathy and I exchanged glances. Brandon sat staring in silence, as did Sarah.

“Do you hear me?” he screamed again. “You get nothing to eat. Now you get upstairs and get in bed. Get up there, I’m telling you, or hit the door and get out!”

She sat in the chair with her head hung in obvious humiliation. I knew she wanted to cry.

“I said get upstairs or hit the door right now!” his voice trembled and his eyes were wild, locked on the top of her head as though he were trying to stare a hole through her scalp.

There was silence again. She shuddered. “Get up there now,” his screams again broke the silence with the ultimatum.

She stood, keeping her gaze fixed on the floor. Without speaking, Sarah stumbled between us and up the stairs. Joe went into the kitchen and fixed another drink, then followed after her.

The door slammed and we heard what sounded like the telephone being thrown across the room. Shouts seeped through the walls, then more shouts and cursing.

Brandon asked what was wrong. We told him we didn’t know.

The screaming and bumps continued for over an hour until after we had gone to bed, but not before exchanging vows to make our morning departure a hasty one.

While swaying back and forth in the sloshing bed, I felt we had been meant to experience the ugly scene between Joe and Sarah. Suddenly there was the revelation of how often this must happen between frustrated couples all over the country. I wondered how widespread the disease of unhappiness and frustration really is.

Unfulfilled in many ways, Joe, who had once had unlimited potential, had started drinking heavily and taking out his failure and frustrations on Sarah. He had fallen into a pathetic lifestyle of sleeping, drinking, anxiety, and boredom.

On the other hand, Sarah, an insecure person too, was noticeably self-conscious about her appearance and felt that providing for Joe was the only way she could hang onto a partner, regardless of how he treated her.

The conflict was sad to witness, but neither Kathy nor I had renewed our licenses as marriage counselors, and we made our exit early next morning.

Joe and Sarah weren’t speaking to each other when we loaded the Lady K. She put her head on my shoulder and cried before leaving for work. “I’m sorry you had to see that last night. God, I’m so embarrassed.”

I held her for a second and told her we would write. She smiled through the tears and said she hoped we would.

Joe looked a little sheepish and avoided looking me in the eyes. I noticed he was fixing a drink when we said goodbye and drove the Lady K from the apartment building amid a mounting snowstorm.

A short time later, we heard that Sarah had packed up and left for California without even telling Joe goodbye.

RATON, NEW MEXICO — Dime-sized flakes were drifting from a concrete-colored sky when we pulled away from Denver. The radio said the snow was beginning to accumulate along Hwy. 25 south and traffic was slowing.

Fifteen minutes later, we were on that freeway, rolling slowly southward between cars and trucks on both sides. The snow was becoming much thicker and a ferocious cross wind was rocking the lady K, making it even harder to drive.

The farther along we drove, the worse the storm grew until finally trucks and cars were becoming stranded on the exits and even in the middle of the highway.

Traffic was moving at 20 miles an hour. The CB radios were buzzing with many calls for help. A snow plow sent light gray slush careening high into the air on the northbound side, but the south lanes were now solid white and several inches thick.

I could hardly see traffic on the road through the blizzard. It was obvious from their expressions Kathy and Brandon were becoming frightened. I was too scared to be frightened.

Suddenly the woman in front stepped on her car’s brakes and the late-model auto slid sideways. I knew if the fat lady K and her 15,000 pounds ever stopped on the snow-packed highway, I’d never get her rolling again, at least not until the road was cleared.

The woman’s car was slipping from one lane to another. An auto on her right slid to the ditch and sat down hard to avoid a collision.

Gathering the CB into my palm, I called the ditched car to ask if anyone was injured.

The voice of a young man responded that he and his wife were alright, but they had a three-month-old baby in the car and the heater had stopped working.

By then, we were a half-mile past them and snuggly wedged between a moving semi-truck and pick-up. There was no way to stop or turn around.

The voice of another man cut in on the channel. Say, how about that fella with the little baby?”

“Yeah, you’ve got him, come on.”

“Is the baby getting cold?”

“Well, mister, yeah, it’s starting to get real cold.”

“Alright, listen now. Where are you?”

“Right beside exit 21. Just below it.”

“Okay, we live about three blocks from where you are. Get that baby and your wife outta the car and wrap ‘em up best you can and bring ‘em on over to the house right now before it gets any worse. We got a warm fire and coffee ready. You’re welcome to stay for as long as this mess lasts.”

“But you don’t know us, mister.”

“No difference…don’t argue. I said get that baby outta there and come on now before it gets any deeper. Just walk straight up the exit to the green house on the left.”

“Ten-four, good buddy. We’re on our way.”

Kathy flipped on the coach radio and said a newscaster said the state police were closing Highway 25, along Monument Pass immediately behind us. More than 50 cars and trucks were now snowbound or trapped by the blizzard, the radio said.

But the Lady K rolled on, without so much as a slip or a shimmy…around the stalled trucks, through the maze of creeping cars…it was as if she was determined to get us through.

Now, I realize it sounds silly, but you don’t understand just how much you rely on a vehicle until you’re faced with a situation like that. We agreed later it was the most suspenseful hour of our trip thus far, except for Brandon’s skull fracture in Sioux City, Iowa.

The snow continued for 200 miles, all the way to the Raton Pass at the New Mexico border. A police report over the CB said the Raton Pass was slick but still passable. We decided to try to get over it before it was closed.

Again the Lady K climbed those 2,000 feet without a strain. In less than 15 minutes, we were entering New Mexico “The Land of Enchantment.”

And there just might be something to that slogan, too. For as soon as we crossed the state line, the sun popped out and blue sky spread like butter on dark bread across the sky.

New Mexico’s mesa lands were like no others we’d seen. Although flat and brown, they are filled with little green growing things. The desert here has a feeling of being alive and thriving.

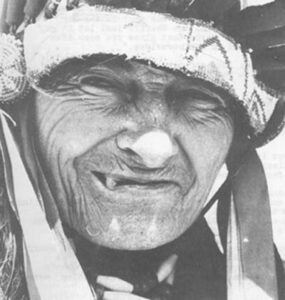

Stopping in Las Vegas, N.M., Mexican boy, with buck teeth and blue-black hair told me not to pull over for the night. “The snow is coming,” he said. “I heard on the radio that it’s going to be snowing here tonight.”

After carefully studying the Lady K and the Honda, he walked back to the driver’s window, kicked the front tire and looked at me. “You come a long ways?” he asked in a Mexican accent.

“Yep, about 17,500 miles already,” I said, handing him the credit card.

“Man I wish I could travel like that. Eeeewowee, I can think of a hundred places I’d like to see.” Scratching his head, he smiled. “Can I come along with you, man?”

“Can you cook?” I looked into his boyish face with a grin.

“Sure, my mom taught me how before she died,” he said. “I can make tamales and tacos real good and you can’t beat my scrambled eggs with chile.”

I asked his name and he said Luis Ortega. He was 19 and had four brothers and three sisters. “My dad works in a factory not far from here. Just about all of us are working now. We have to, but we don’t mind,” he said.

Luis said he pumped gas for an old man who owned the station. “I guess I work 40 or 50 hours a week,” he said. “But it beats doing nothing, I guess. Say, man, are you gonna take me with you or not? There was a sparkle in his eyes. I actually thought he would hop aboard if I nodded okay.

Smiling, I retrieved the credit card while asking if he could pick anywhere in the whole country to go, where would it be.

He hesitated and scratched his head again before looking up with a grin that showed every tooth in his mouth.

“I’d like to go to New York, man.”

“Oh. Why New York, Luis?”

“Cause that’s where the action is. You can make it good in New York. They got anything you want in that town.”

Another car pulled beside the pumps. A black cord across the pavement sounded two bells inside the station.

“Well, Luis, I can’t take you with me today,” I said, “but here’s my address and if you’re ever passing through Arkansas on your way to New York, you can sure spend a meal and a night with us.”

He smiled that toothy smile again, and took the card. “I’ll just do that, man. Yeah, one day, I’ll just do that.” The Lady K swung about and we waved at Luis.

Albuquerque…a city where I spent seven years of my life, waited three hours southward and we decided to push on to the KOA there. Kathy put on a pot of coffee.

The sun was setting behind the mesa when we rolled through Santa Fe, probably one of the most quaint and beautiful cities in America. The sunset made it seem even more unreal.

A hungry Brandon broke the spell by puncturing a can of tuna fish and letting all the smell run out.

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Sitting at the kitchen table of the Lady K, I can stare across a shrub-filled mesa that races to the foothills of the Sandia Mountains on the eastern edge of the city.

There is the feeling welling inside that it’s time for me to make several profound statements of revelation about America…to tell those following our travels what’s out here beyond their city limits signs.

But, as it is every time I feel like this, the revelations just aren’t flowing. So I begin to recall those we’ve met during the past eight months and 18,000 miles.

There must be a hundred faces and personalities fighting for dominance in my mind’s eye. For instance, there’s Dorothy Boswell from Memphis, who had telephoned an elderly woman she’d never met every morning for seven years. just to make that lady happy.

I can also see the face of Jim Moffett, the chief deputy of the late Buford Pusser for six years in McNairy County, Tennessee, and a man who shattered my illusions of Pusser’s “Walking Tall” image.

Dickey Jacobsen, a young fellow from Louisiana who had guided a wagon and mule team for three weeks in the Bicentennial Wagon Train is another whose face and words I remember along with those of Jeff Hine and his sister as we toiled together in the tobacco fields of North Carolina.

I get a feeling that each person, place, and experience has been like a piece in a big puzzle and that it is up to me to put the puzzle all together and show you what it looks like and what it means.

With eyes closed, I can picture John Mordus, the congenial Detroit truck driver who took us home with him from off the road. There’s also Urva Quick Bear sitting beside the highway at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, and Jack the legless pencil peddler on the sidewalks of downtown San Francisco, who taught me much about life on the city streets in the hour I spent beside him.

I know there are the bad…the ruthless people out here, too…those who would slash a tire or a throat for a few dollars or just the thrill.

I realize the multitude of problems that exist all around us…drugs, crime, corruption, bigotry, hatred, and murder.

And I know I haven’t seen it, which makes me feel like I’ve failed in many ways to give others a complete picture of this country. But neither can I understand why, if the country is filled with the bad, we have encountered so many givers rather than takers.

A small black and red plane glides by overhead breaking my thoughts. It seems to stall against the pastel blue sky, then the engine coughs and roars and the man-made bird continues flapping past the window.

I return to wondering if an accurate picture of America’s people exists at any given moment. It’s been shown that the best-read daily news accounts are primarily negative stories. Only a few positive articles contain enough human interest each day to catch and hold our attention, yet I question whether enough emphasis is given by America’s journalists to seeking out those pieces.

In our short time on the road, I’ve found the country to be filled with ordinary, everyday, interesting people whose stories can be captivating and positive reinforcement to any reader, but there seems little interest in telling them.

Kathy breaks my thought again as the door flies open and she hauls in a bag of groceries under one arm. Brandon rushes in, grabs a racecar and says he’s going to “find a friend to play with.”

After the food is de-bagged and stored, we sit to talk for a while about our journey.

We both admit we’re tired. Months on the highway have a way of grinding you up and leaving you lying beside the asphalt like a flattened opossum who wasn’t watching.

The conversation turns to our mutual longing for some time behind four sheet-rock walls, a place with more than one door to hide behind when we each want to be alone a while…like all of us do.

Kathy wonders if living together 24 hours a day has brought us closer together or farther apart.

“I think closer, but we’ll know when it’s over. If we’re still living and sleeping together, it’s bound to have brought us closer,” I answer.

“I seriously doubt if Billy Graham, Oral Roberts, or Rex Humbard and their wives could take an endless, concentrated diet of spouses and children without being tested.

Kathy smiles and nods. “So much has happened,” she says. “It’s a wonder we’ve been able to retain any of it.”

“It all comes so fast and furious that we really don’t have time to sit and reflect on it now. When one experience ends, another’s beginning.”

Later in the evening we drove past the home where Rue and Elaine Masterson spent seven years raising two boys and a girl.

It still looked as it did in the early 1960’s…long, tan, made of stucco like many houses in Albuquerque. A little girl peered from the window as we slowly drove past. She waved and Brandon waved back.

The city seems to have leapt across the desert floor like a jack rabbit in almost every direction during the past decade.

Tall buildings now stand downtown where none were before. Housing projects and subdivisions dot the landscape to the very foot of the Sandia Mountains on the east and continue their sprawl northward toward Santa Fe.

I chuckled at remembering my years as a shoe salesman for the Sears store downtown. A heavy-set woman strolled into the department during a summer afternoon, I recalled, and said she wanted a black loafer in a “size-six, quad-E” shoe.

All I could find on the shelf was a size 10-D, which fit in width, but looked like dual Queen Marys in length.

She had told me they were fine, and left smiling.

Kathy kept driving while I continued to remember. We drove in front of Jerry Markland’s house. Jerry once rode to school with me every morning and was known for his calf-sized brown eyes, good looks and sense of humor.

He was drafted and became a helicopter pilot. He was shot down in Vietnam and died.

When the sun changed from yellow to orange then pink and deep purple, we drove to the mountains for a view people once wrote songs about.

Brandon said Albuquerque at night looks a little like a giant Christmas tree covered with a million tiny, colored lights.

It’s a view for people who want somewhere special to go alone and think, or court someone else in a fantasyland, or share something spectacular with another.

To me, it’s the prettiest sight in the Southwest, and Albuquerque was one of the cleanest, best-organized cities we’ve seen in America.

When we left the city, the Lady K was aimed eastward along Route 66. It was dark, Brandon was asleep…and I just felt like driving.

WEATHERFORD, OKLA. — I’ve always been one of those weird ones who enjoyed driving after dark. Kathy said it’s probably the vampire in me. But for whatever reason, there is peace in settling behind the wheel amid all that blackness and watching headlights glide past.

It was during one such evening, when the rest of the crew was fast asleep, I met one of the most interesting people of the journey, although I never saw his face.

After navigating Route 66 for several hours, my eyelids were starting to droop and thoughts of getting off the highway were prompting me to look for a good spot. Oklahoma City was still more than 100 miles ahead.

A call on the CB broke the silence. “Break one-nine for that ole motor home up ahead of me there.”

Glancing in the rear-view mirror, I noticed car headlights growing closer. The black plastic microphone fit snuggly in my palm. “You got the motor home.”

“Hey, good buddy, let’s drop to channel one-four where we can conversate a bit,” his voice was clear and seemed to have a slight accent.

We changed to channel 14, where I quickly discovered the caller was a Cajun from New Orleans who had been laboring on the Alaskan pipeline for a year. He was headed “back home with a fistful of greenbacks and a song in my big ole heart.”

Calling himself Mumbo Gumbo, he spoke so fast I sometimes had to ask him to repeat.

“Hey, I want to tell you that was no particular fun working on that pipeline, my friend,” he said. “In fact, it was unfun and muddier than chocolate pudding. But I made enough to go home and start a business…and that’s what I went for to begin with.”

“How big around is that pipeline?” I’d always imagined it as being bigger in the middle than the Lady K.

“0h, my friend, the Mumbo Gumbo tells you it’s smaller than you think it is in the middle around. I think most people believe it’s bigger than a house, but I couldn’t get my car inside…at least they told me never to try that…ha, ha, ha.”

I asked if it was true that a lot of American women have traveled to the work sites in Alaska to set up prostitution businesses in mobile homes.

“0h, that’s for certain sure, good buddy. As a matter of fact, I enjoyed my off hours so much that I married one of those girls…at least I did for a while. It was cheaper, my friend, don’t you see?”

“Many of those women made more money than us poor workmen and theirs was all free of tax. I once heard a story about Mary Lou who came with a hundred dollars and left with more than a hundred thousand in just a short time. She was smart. She never got married.”

Headlights on a late model yellow car swung around the Lady K and I caught a glimpse of his face in the darkness. Mumbo Gumbo was dark-skinned and his hair was black. That’s all I could tell.

“Hey, my friend, I’ll take your front end for a while,” he said.

I asked about his life in Louisiana and he told me a story about “wrestlin’ alligators and stranglin’ snakes and catchin’ crayfish and skippin’ school.”

“My mom and dad, they died in a wreck when I was just a little one, not more than six or eight,” he continued, “but I had eight brothers and four sisters and we all got along alright. I’d like to go back now and buy a farm big enough for the whole family. Who knows, maybe I will do just that, my friend.”

He continued, explaining how he had enlisted in the Army and fought in Vietnam. Part of his ear and shoulder were missing as proof.

“That Vietnam was no fun, nosiree. I had a good friend who was shot right between the eyes when he was beside me in the jungle.”

“You don’t know what happens to you, my friend, to see a fellow you’ve ate and drank and cried with shot and killed before your very two eyes. His whole body just shuddered and quivered there on the ground before me and all I could do was scream, but it didn’t do no good, no sir. He was gone and wouldn’t be back.”

When Vietnam ended, Mumbo Gumbo said he left the Army and went to work in a New Orleans factory for a while. He quit that job because “working in a factory is like standin’ and flushin’ a commode all day. Pretty soon you’re moving you’re arms up and down in your sleep.”

The cold Alaskan climate, far different than the relative warmth of deep south Louisiana, didn’t bother Mumbo as much as the mosquitoes, he said.

“I tell you those mosquitoes, they were bigger than cockroaches and twice as hungry.”

“I even swallowed one and I swear he went down my throat like a hard-boiled egg that wasn’t chewed at all. At least, I didn’t have to eat dinner that night, ha, ha, ha.”

Curious about his brothers and sisters today, I asked if he ever heard from them.

“Oh sure I do. Three of my brothers work for a fisherman and two more are mechanics. One died last year from a heart attack and another one, he works on a farm. The one just older than me he’s done really good. He’s got a job with the state. All my sisters got married up and had kids comin’ out their ears.”

“I guess I’m the only one with the itchy britches. I like to look around and see what’s all here before I’m not here anymore.”

The slivered edge of a brilliant sun had crept to the horizon and Mumbo Gumbo was out-distancing us to the point of poor reception.

“We’re going to be stopping for some rest,” I called to Mumbo. “How about you?”

His voice was faint and scratchy, but I could still hear.

“No, not me, for sure. I’ve got many miles to cover yet and some more friends to make on the highway here. Besides, I’ve got a little baby here beside me and she’ll wake up I know if I stop this car.”

“I forgot to tell you about her. When I got married up, we had a baby together and my wife, she didn’t want her, no sir. But I wanted the little one for sure and now we’re together, my friend…all legal and everything.

“Why she’s the very best thing, besides crayfish creole that ever did happen to ole Mumbo Gumbo.”

Those were the last words I heard from Mumbo. His voice crackled and faded as quickly as it had come. I wondered for a while if our conversation had been just a dream or something I conjured up to stay awake.

But it hadn’t been a dream, only another human being in the darkness along Route 66. I was glad I’d had the CB radio to tell me about the people in that yellow car.

Received in New York on January 5, 1977

©1977 Mike Masterson

Mike Masterson is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Sentinel Record (Hot Springs, Arkansas). Mr. Masterson will travel throughout the U.S. with his family and write about the country and its people in 1976. This article may be published with credit to The Sentinel Record and to Mr. Masterson as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.