HOT SPRINGS, Ark. — The drab exterior of Martin’s Recreation Center and Cafe isn’t much different than the inside, a 60-year-old brick building sandwiched between clothing and shoe shops along Central Avenue downtown.

Those who don’t put much store in appearances venture behind the door each day into a world of self-proclaimed comedians and experts, along with amateur philosophers wearing everything from business suits to Salvation Army stock.

The motley gathering takes form about seven in the morning and the exaggerations, comparisons and judgments continue until the doors are locked at 5:30.

Martin’s could be the same place my grandfather used to take me twice a week, under another name in a different town 20 years ago.

In that hole in the wall, a 50-cent bowl of chili and beans with crackers was the specialty. But despite good food, most men came to trade wit and join in continuing bull sessions.

The Hot Springs cafe is a salty, colorful nook where Damon Runyan could have retired in bliss. It’s also a haven for nearly 200 who have come to this Southern town seeking moderate temperatures, inexpensive rooms, companionship and a darn-good buck and a half meal.

Route 66 had led us back from the Southwest for a brief rest and the chance to put the last eight months and 18,000 road miles into some perspective. I had long been intrigued by the atmosphere at Martin’s so the decision to spend some time on a stool behind the weather-beaten sign was an easy one.

For me, the place represented a non-academic, human side of America; a niche where folks still say what they mean — out in the open for all to hear.

The plate-glass window in front usually features a portly, middle-aged man sporting a white apron and cook’s hat. His morning performances for passers-by includes the likes of flapjack flipping, egg basting and grit grabbing with the aid of an over-sized spoon.

Carroll Burtchfield is an amiable, 62-year-old with a growling voice that resembles a ton of gravel rolling off a truck bed. He seldom looks up from a hectic pace at the vintage stove to acknowledge those who peer through the glass. Several huge metal pots rest on the back burners beside him.

Inside those frothing cauldrons bubbles the days lunch offerings, fresh vegetables and greens of some kind, plus beans and always a pot of beef stew. Beneath, tucked securely in the stove’s belly are biscuits by the dozens and…only on Friday…large slices of corn bread.

Carroll came to Hot Springs 12 years ago after giving up two restaurants in San Antonio. “I lost one outright and made a little money by selling the other,” he said. “But then that’s the way life goes. This will probably be my last year cooking here. I want to retire for good.”

Forty or so revolving vinyl stools line each side of the narrow cafe. There are no tables, only twin 30-foot counters, which means everyone else sits either beside or behind you. An antique wooden fan is attached to the ceiling above the front door and those who don’t come in the back door sometimes bump into those waiting to pay their tabs in the doorway.

No one gets a ticket for their meal at Martin’s. You just step up to the register and sing out what you ate. Someone will tell you what it cost, which is almost always less than you figured on paying.

Next to a wall behind the right counter is a glass freezer stuffed with slices of pie, hunks of cold cuts and meat, cartons of milk and large cuts of cheese. Boxes of cold cereal and little cans of soup with yellowed labels sit on a shelf beside the icebox. But the discoloration is understandable since the best soup at Martin’s is what Carroll ladles from the top of that stew pot boiling up front.

Grabbing a vacant stool between two older fellows, I rested my head in an open palm and eavesdropped on conversations around me. Two men were arguing about a referee in a basketball game. Three others were talking local politics and another pair were solving the problem of grounded Liberian tankers.

“It’s a crying shame,” one said. “I think it’s espionage, by golly, and you can’t tell me different neither. Some other country’s trying to ruin our coastlines and our fishing…”

A short man in a red baseball cap, glasses and silver hair above his ears asked what I wanted to eat then promptly bellowed the order to Carroll who repeated it while reaching for two eggs and several strips of bacon.

He was Ted Skirvanos, a semi-retired horse racing enthusiast from Hot Springs who just happened in one afternoon during a wild rush. “I looked at the crowd, then asked Jack, the owner, if he needed help. He said to grab an apron and jump in anywhere, so I did. That was three years ago,” he said.

Another man wearing a Cossack hat and scowl plopped down beside me, interrupting Ted. Taking the man’s order, he screamed it to the front. The Cossack cocked an eye toward me and in a voice more than a whisper said, “whippersnapper.” I guess he meant me.

The Jack Ted mentioned was also scrambling around behind the counters. He was, I later learned, Jack Irwin, a 41-year-old bundle of energy who perspires almost as rapidly as he eliminates the needs of those seeking sanctuary and sustenance in the small cafe.

I watched the slim, dark-haired man hurry up and down the aisle, taking orders, refilling empty cups, telling jokes and serving up an endless stream of steaming plates loaded with breakfast.

During short breathers Jack paused to gulp down glasses of tap water, replacing what was going down the sides of his cheeks. The longer I watched his routine, the more tired I became.

Ted wandered back a while later and told a story about how Jack had personally cared for a lot of the old men who lived in the dilapidated hotels downtown.” He’s fed a many when they didn’t have a cent to their names. He’s even taken some home with him and fed them and given them his own good Scotch whiskey.

And he’s also buried a lot of the men,” he continued, “the ones who didn’t have anyone no more. This place was all they had in the end and Jack just felt sorta responsible, I guess.”

The cafe had been in the same spot for decades, but Jack wasn’t certain of the exact date when Martin’s doors opened for the first time. “The best estimate is sometime in the mid-1920’s,” he said. Jack’s father, Bill, bought the place from a man named Martin and decided to keep the name. Bill Irwin put Jack to work behind the counters when he was only 13. He’s been there since.

Bill Irwin died a few years back and Jack soon became the owner. His mother, a soft-spoken, friendly woman named Mary, lives in town. Jack said she’s still an inspiration that keeps him hustling.” I guess we serve 350 to 400 meals a day here,” he said, “that includes all the meals for city, state and federal prisoners in town.”

There were about 30 people in the cafe. At the back of the room, seated in hard-backed chairs around a single snooker table, were at least ten others deep in conversations.

Smoke from a dozen cigarettes and cigars spiraled into the room as I glanced down the counter to see what others were eating. The whippersnapper was having four scrambled eggs, hash browns, toast and bacon. A man next to him was hunched over his plate, staring blankly at two fried eggs. A blue sock hat was pulled to his ears and the collar on a tattered coat was turned up.

Ted said his name was Perry Como, a regular customer they’d nicknamed for some reason other than singing ability. I never found out why.

After a few minutes, I went over and sat beside Perry Como. He had downed half of a draft beer and all his coffee, but there were only a few bites missing from his eggs. I judged him to be in his late 40’s and no doubt depressed about something…maybe everything.

We soon struck up a limited conversation, that’s where I do most of the talking. He told me his name was Jones and he lived “in a flop joint.” I knew he didn’t feel much like talking, but he did tell me he had come to Hot Springs from Chicago about five years ago because of arthritis.

Jack, who was listening to us, joined in. “I’ll tell ya about ole Perry Como here,” he said with a chuckle. “Three years ago he was doing great, back before I hit him in the knees with a baseball bat. He hasn’t been the same ever since. Right Perry?”

Jones flashed a quick smile, the first I’d seen from him. “Yep, Jackson, that’s just what happened all right,” he said, picking at a sliver of egg with his fork. He sighed deeply and looked into the plate. “I guess that’s about all I want.”

I watched him hesitate before explaining to Jack how his check hadn’t come in for that month. Jack said not to worry about it. He could pay next time.

Thanking him, Jones eased from the stool and made his way through the crowd to the door. More and more were filing in and claiming stools. Intermingled aromas of bacon, stew, beer, coffee, cornbread and smoke filled my nostrils. I noticed how, included in the customers were black men, something no one saw in the South just 15 years ago.

Across from me was the fire chief and, over there, the coroner, a politician and a cab driver all blending in with those who no longer had much of anything to form a melting pot with more variety than Carroll’s stew.

A well-dressed man in his early 60’s took Jones’s stool. His name was Bob Garvin, another regular whom Ted called the resident philosopher of the stools.

“I’m not in the same shape as a lot of these guys who come in without anything,” he said. “I have a decent pension that allows me to live comfortably, and that’s because I planned it that way a long time ago.”

Bob said he’d been married once, but now lived alone.

“I have kids,” he said, “and I go to see them several times a year.”

I wondered what Martin’s meant to him and the others who frequent the cafe.

“Well, places like this are the social gathering places for those who can’t afford to be an Odd Fellow or an Elk. Most of these guys came up in the Depression years when fellowship between people was about all the entertainment there was.

“They have that right there in common and, believe me, if you survived those years, you got something in common. Trouble is, places like this are dying out as this Depression generation dies away. Now you got the fancy, carpeted chain restaurants with piped-in music and middle-class prices. Most folks would probably think this place was too crusty to come in with a family for a meal.

“What they don’t realize is how much character and enjoyment this cafe holds. Twenty years ago you could have found these places in towns and cities everywhere. We’ve got an extraordinary number of people over 65 in this town, so Martin’s continues to thrive.”

“I’ll also tell you this, young fella, there’s not a better cup of coffee or a better meal for the price anywhere in the whole country and I know…’cause I’ve been out there a whole lot.”

During my mornings in Martin’s, I also met many others who made the place a cultural landmark in this small city. There was Cecil Ison who, at 46, had been bartending and wiping counters there for 25 years.

It was Cecil who took me aside one day and wrinkled his face in a serious expression. “Say,” he said, “did you hear that old so-and-so died yesterday?” I told him I hadn’t.

“That figures,” he continued. “You can hear some of the darndest things around here. Heck, it got out a while back that Elvis Presley had died. These fellas will fool you if you don’t watch it.”

Then there was Percy Harrod, a 60-year-old retired sergeant who has been hauling dirty dishes back and forth behind the counters for nine years. Percy was a stooped man with dark-rimmed spectacles, ruddy complexion and a penchant for staying busy.

It never failed when I was there that Percy was bent over a soapy washbasin near the back, or collecting empty dishes in a plastic tub. He seldom smiled and didn’t speak much. But then, very few spoke to him that I saw.

I met Richard Lockwood, a retired cab driver from San Antonio and another feisty little man, his name escapes me, who had been a merchant marine and had sailed around the world 18 times. The list of stories would fill a book or two…Tom Finley, Al Menifee, Glen Olson and Don Moody all came to Martin’s six days a week between seven and 5:30.

One I didn’t meet was Dalene, Jack’s wife, who spends most of her time helping him behind the counters. She was out of town for a week. “Man,” Jack said, “she’s really the one who hustles around down here. She keeps me in line.”

Somehow, I couldn’t see anyone outdistancing Jack Irwin in his domain.

BREAUX BRIDGE, La. — Brilliant rays from a mid-afternoon sun were filtering through winter-bare branches of overhanging oaks as the Lady K made her way down Rees Street in the middle of Cajun country.

More than 5000 people thrive together around the banks of murky Bayou Teche in this small Evangeline-country community that prides itself on being called “Crawfish Capital of the World.”

During a right turn toward the downtown section, I noticed a plantation-styled home resting on a hill to the left only a rock’s toss from the Bayou.

It was a magnificent red brick house, sheltered by dozens of trees…nestled to the short metal bridge for which the town was named.

The city’s center was primarily one narrow main street with older stores and buildings on each side. Dark-haired people strolled the sidewalks speaking fluent French. It was like we had entered a different country.

Later that afternoon, at the city hall, I learned the rambling home we’d seen earlier belonged to an elderly attorney named Grover Rees and his wife, Consuela.

He had retired from a legal position with Gulf Oil more than 20 years earlier and the Reeses had reared six children.

I also heard he was locally famous for rascally wit and his knowledge of Breaux Bridge and its history.

The steel coupling slipped easily from the towing ball on the back of the Lady K and Kathy eased the car backwards a few feet. Piling in beside her, we drove back to the bridge and over it, taking the first right turn into a winding driveway.

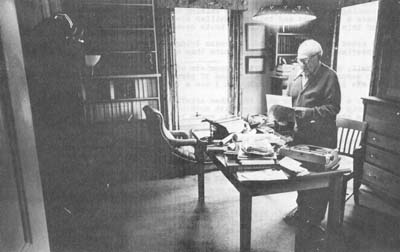

I wanted to meet this Grover Rees and hopefully pick his brain a bit about the town and its people. Touching my finger to the bell, I waited looking out at the muddy bayou. In a moment, a short, balding man with a protruding stomach and green robe, eased open the white door and grinned.

“And what can I do for you young fella?” Despite his 85 years, there was a distinct gleam in his eyes. I told him I was a journalist and the edges of his mouth turned up even farther. “Well,” he said, “come inside anyway.”

We followed him into a cluttered library and study where he apparently spent most days. Papers were strewn across the top of a large wooden table. A portable typewriter rested on one corner.

Books that wouldn’t fit into his over-crowded library shelves were stacked on several shelf tops. A thesis on the history of Louisiana lay open on an antique chaise lounge beside the window where he had been resting before our interruption.

Motioning us into appointed chairs, he excused himself for a moment and returned in a sweater then dropped into a seat behind the table. “Now tell me who you are, where you’re from and what you want,” he said in a labored voice.

I hurriedly explained about my search for people across the nation, as he cocked an ear to listen attentively. A cucumber-sized cigar appeared in his wrinkled hands and he brought it to life with a lighter laying beside him.

“So you want to know about Breaux Bridge and the Cajun people,” he said.

“Well, I suppose I can help somewhat, since I married a Cajun girl more than 50 years ago. Consuela is a descendant of one of the founders of Breaux Bridge, which was originally called La Pointe.”

“Ten years before America claimed her independence, a group of Acadians, who were French deportees from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, arrived here and settled a small area called La Punta by the Spanish.”

“The colonies won their freedom from England a decade later, and the Louisiana property became part of America’s possessions in 1803 when the Acadian refugees, or Cajuns, eventually became U.S. citizens.”

“As the settlement grew, a bridge was built across the bayou connecting lands owned by The Breauxs family. Later, the name of the settlement was changed to Breaux Bridge.”

Pausing, he flicked the lighter once again while puffing ferociously to revive the lifeless cigar. I noticed several boxes of Optimo Admiral cigars on one ledge of a bookcase. A half-filled can of potato sticks sat beside them.

“Now then,” he continued, “from those beginnings, there has developed the largest concentration of French descendants more than anywhere else in the country. Nearly half a million French Americans live in this area of southern Louisiana.”

He said the Acadians, or Cajuns, are somewhat clannish toward strangers, but not unfriendly. “My friend,” he said, “if you were to move here, not speaking French, you would be known as ‘an American’…perhaps that will give you an idea of what I mean.”

Grover went on to talk about parts of his life. He was one of four children born in Breaux Bridge on Halloween, 1891, to Welsh descendants. After public school, he went to LSU, then to Harvard, where he finished in 1915.

In 1924, he married Consuelo Broussard and shortly afterwards became counsel for Gulf Oil, representing their interests in Colombia, Venezuela and Europe.

He said he moved back to Breaux Bridge in 1955 and he and Consuela built this dream home beside Bayou Teche. They had six children and now have 30 grandchildren and one great grandchild, Grover Rees IV.

He has since spent thousands of hours in the room we were in; reliving a career and continuing to broaden himself by reading hundreds of books.

I asked if we could meet Consuela, who is now 74. He said she was napping and would probably be up later. “You know,” he interjected as an afterthought, “sometimes, on the holidays, when all the kids and grandkids are piled into the house and all 50 or so of us are running around making noise and raising heck, well…sometimes I have a few drinks and tell my familiar story about how I started all of this crowd.” Another smile broke across his face and he laughed.

I asked about his boyhood in Breaux Bridge and about catching the crawfish, which made the town more than a tiny circle on the road map.

“Well, nowadays Breaux Bridge consists of about 6,000 people. About 63 percent of those are white and 37 percent are black, which is a whole lot more people than when I was a lad.”

“For a small boy or girl back then crawfish hunting was the thing. A trip to the bayou equipped with nothing more than a piece of meat on a string, a bucket and a net, would bring at least enough crawfish to boil.”

He paused and chuckled to himself. “The only bad part of those hunting parties was when we got home with feet and legs full of dry mud. Mom always insisted that they be washed before bed — that really hurt.”

“Bathing facilities, if one could call them that, was a large tin tub installed in a combination washroom and tool shed located near the well.”

He went on to explain how children of Breaux Bridge grew up looking forward to three special times, New Year’s Day, Easter, and Sunday Mass…when the boys were allowed to walk the girls home from services.

“Our family still exchanges gifts on New Year’s Day rather than at Christmas, according to Cajun custom,” he said. “It goes back to a belief that Christmas is strictly a religious celebration and New Year’s Day is a more appropriate time for well wishing and giving presents.”

“There used to be many fiddlers and dances in the town where everyone would come out and have a good time. Nowadays we still have some get-togethers, like the Crawfish Festival every two years when everybody comes and eats crawfish and gets drunk and falls down. It’s great.”

As he talked, Grover fished around in a drawer before coming up with a green, paperback book. He handed it to me. “You may have this mister journalist. It’s a copy of a book I recently wrote about Breaux Bridge.”

I looked at the work, entitled “A Narrative History of Breaux Bridge, Once Called La Pointe,” then thanked him.

“I might add,” he continued, “that the local book store has sold 300 of those for $2 a piece.” I took that as a hint he wanted me to pay, so I offered. He refused.

“No,” he said. “I just like to tell people that. It sounds good and makes me feel important.” We shared another hearty laugh and I told him good-bye, but not before asking directions to the nearest crawfish restaurant.

Grover aimed us at a place called The Crawfish Kitchen Restaurant which was owned by a Cajun family. There we met a friendly, middle-aged woman named Marion Naquin.

Marion sought us out as we sat contemplating the menu. She and her husband, Elmer, had recently built the new restaurant.

She was a native of Scott, Louisiana, only a few miles away, but added she had lived in Breaux Bridge for 23 years.

I had earlier noticed the color portrait of a handsome young boy hanging above the cash register and I asked if he was her son.

“He was,” she said, struggling to maintain the broad smile of moments earlier, “he, uh,…he died last May while we were building this place.”

I learned that Lenny, who was then seven, had been playing with two friends in the water of a deep bar pit only a few yards from the restaurant. There was an inner tube and the friends said he just disappeared under the water.

“But,” she continued, “I have six other children who are healthy and happy and I’m thankful for that.” Dark brown eyes sparkled again and she went on to suggest the crawfish etouffee, which we tried and found surprisingly good.

In the middle of dinner, the restaurant phone rang and Marion summoned me. I had no idea who’d be calling at that time in that place.

“Hello, Mike, is this Mike?”

“Yes it is, Mr. Rees. How are you?”

“Well, you recognized me, hee, hee. Now Mike, I just wanted to tell you how to go as you head southward. I forgot to tell you while you were here. I’ve got a schedule all worked out for you…”

And, as Grover Rees carefully outlined our route for the following week, I watched across the room as my once warm and tasty etouffee got cold and Kathy got stuffed.

The next morning, we drove the Lady K deeper into Acadia, headed toward the salt mine at Avery Island.

AVERY ISLAND, La. — Belly laughs and guffaws shot through the steady rumble of a dozen conversations inside the white frame hall. More than 30 miners were guzzling cans of beer and inhaling handfuls of potato chips while a steady stream of tired bodies kept surging through the open door.

The first shift at International Salt Mines, about 500 yards down the road, was over and I’d been asked to the afternoon beer bust in celebration of an accident-free month in the mines.

Four Cajun miners stood beside me, talking about their work. The conversation was mostly about troubles on the conveyor belts they had experienced early that morning.

Across the room, floored with wooden planks, two rowdy black men were having a chug-a-lug contest with four cans of beer. Another crammed eight or nine unopened cans from the bottomless supply of an icy metal tub into a paper sack. Several chided him for stealing part of their party.

He smiled at the hecklers and walked out the door. “Well, I got friends outside,” he responded over his shoulder. “I gotta take care of friends don’t I?”

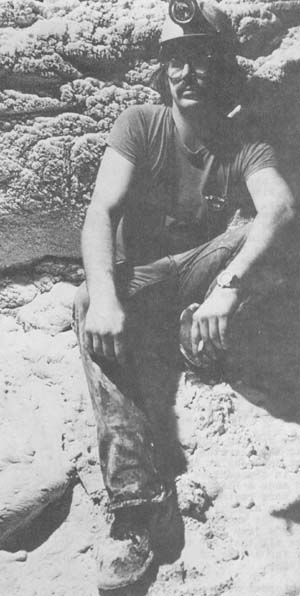

Two young, stocky men were seated alone near the back and I slowly made my way toward them. Reggie, a dark-haired fellow with a full beard and a checkered flannel shirt, said he’d only been at the mine for three weeks.

“I’m still an outsider around here, so to speak. The union guys are suspicious of newcomers at first and they’re not quick to let you in with the regular fellas…that’s why we’re sitting alone over here.”

The other miner, a tall man with a handlebar mustache, said his name was Lionel. He had been at International Salt five weeks.

They worked together at the lowest level and said they’d spent the past two days filing on a bolt that went to a piece of heavy construction equipment called a loader.

“It’s sorta ridiculous,” said Lionel. “I mean spending all that time just to get a loader going. But I think we finally got it fixed today.”

Reggie was single, Lionel said he was married and lived in nearby New Iberia.

I wondered how uncomfortable it was being the black sheep at the party. “Oh, it’s uncomfortable,” said Reggie, “But I’ve been through it before up in a copper mine in Maine. After a while, they’ll accept us and everything will be smooth.”

Lionel rubbed the foam from a fresh beer on his grimy blue jeans and nodded in agreement. Both were downing the brown and white cans like they were filled with water, making certain to ritually crush each empty between their fingers.

In Arkansas there are several coal mines and one of the most dreaded hazards of that profession is a scourge called black lung.

I asked Lionel if salt miners faced any such disease. “Not that I know of,” he said. “I don’t think any thing could live in all that salt for very long. I don’t mind being down there and no one has ever mentioned any sicknesses connected to salt mines.”

“Maybe not,” Reggie interjected, “but look here at this cut on my hand…been there two weeks now and still hasn’t healed up. Salt will sure keep something like that irritated. The cuts just don’t wanna heal.”

“You know man,” he continued, “we like you and all that, but you really need to mingle with other guys, too. Like we said, they don’t exactly love us yet and, well, some of them are kinda giving us the bad eye ’cause you’re interested in us and all.”

He was right, there were some hard stares from others, so I wished them well and strolled back into what had become a boisterous, fifth-beer crowd.

“Hey man, take our picture,” one shouted. Four men in yellow hard hats shoved together and flashed silly smiles.

“Hey, don’t forget us over here, too,” two others stood beside their table and stuck out their tongues. Finally, to satisfy the growing number of hams, I draped the Pentax around my neck, climbed into a hard-backed chair and photographed the whole group from one corner.

These salt burrowers were a rambunctious, fun-loving lot who obviously knew how to unwind and enjoy just being alive, especially the more they drank.

Many had come to miner’s hall intent on pickling themselves until well after the sun had set. Afterall, this one was on the company.

At one table, early arrivers fortunate enough to gather around one of the four tables with chairs were telling dirty jokes and enjoying them so much they often found it difficult to stay in their chairs.

A middle-aged man who had tired of standing decided to sit down in another’s lap. “If he dances with him, I’ll buy a round for the house,” some wit in dungarees yelled. The house exploded in laughter.

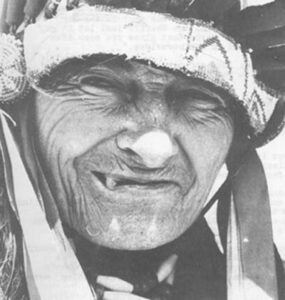

A tall fellow with coal-black hair and brown eyes said in thick Cajun accent that he’d been in the salt mines for 12 years and wouldn’t do anything else or live anywhere else but in the company town.

He went on to explain how Avery Island wasn’t really an island at all, but a section of land raised slightly in a dome from the salt pushing up beneath. It was surrounded by a narrow bayou.

Another named Henry, said a beginner with no experience would probably earn $4.50 an hour to start in the mines. All newcomers start at the top and eventually find themselves downstairs in the dimly-lit tunnels.

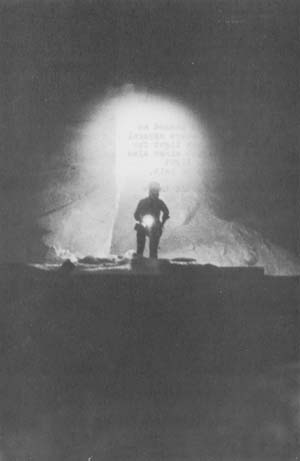

Earlier that day, Kathy and I had donned enough safety equipment for an Apollo flight and ventured down that aged elevator shaft with a young man named Mike Phillips, who managed the office at International Salt.

Above ground, Joe, the mine’s safety inspector had been patient in explaining how we had to carry along flash lights, emergency breathing apparatus, safety glasses, steel caps for the toes of our shoes and white hard hats to comply with federal restrictions.

Visitors had been barred from the mines more than ten years ago after a shaft collapsed in another state.

Joe had also ominously told us “when you place the emergency breathing piece in your mouth and it begins to burn around the edges, don’t take it out whatever you do. If you do, the burning will instantly spread into your lungs and you will die.”

At that point Kathy said she’d changed her mind about going down. “Mike, he didn’t say if…he said when you put it in your mouth…when, Mike, when.” Nevertheless, we went.

The elevator that was to drop us into the enormous man-made caverns didn’t look at all like the streamlined, Regency-Hyatt express I’d expected.

It was yellow metal and very small. The load limit on the sign said 15 men, but it looked like that many people would have to be standing on top of each other.

Before boarding, we followed the other Mike into still another room where he issued us a numbered metal tag, “so they could identify our bodies just in case…”

In the elevator, Mike yanked several times on a slender rope cord which was a code to tell someone to begin lowering. Within a few seconds, the last ray of sunlight had vanished and we were in the blackest of blackness for a 15-second drop into the shaft. Waiting at the bottom was Harry Anderson, the mine’s production supervisor. He walked us to a salt-encrusted jeep and motioned for Kathy to sit in front. The two Mike’s fended for themselves in the metal bed behind. A few coiling lights near the elevator kept darkness at bay, but in a moment we had made a left turn and were racing along a highway beneath the earth. Harry’s jeep lights were all that lit the way for a mile of driving. He stopped several times and aimed a powerful spot light toward the uppermost reaches of the shafts more than 100 feet overhead.

The tunnels were almost that wide to accommodate the giant caterpillar machines, dump trucks and front-end loaders that occasionally passed us.

Harry said all of the heavy machinery had been lowered down that elevator piece by piece and reassembled at the bottom.

The road we were following, I learned, was nothing but the salt that was there mixed with water. The solution had dried asphalt hard.

From time to time we passed an active mining area where several lamps provided enough light for men to work by. Each miner also A had his own battery light attached to his hat or belt.

As Harry drove, I could taste salt collecting around my mouth and on my face. It was in the air, all around us in the form of gray dust.

Harry said what I saw was act usually a combination of exhaust fumes and salt dust. “You’ll notice it’s not hot down here,” he said, “That’s because the temperature stays at 65 degrees.” To our right and left were endless lines of canvas conveyor belts hurrying their cargo of freshly mined salt to the surface, a job that was done only a few years back by strong backs and oxen. Two miles passed. Harry swerved his jeep to one side and hopped out to examine a minor problem on a conveyor. Leaning back, I watched the searching eyes of some huge mechanical monster pass another white-eyed subterranean beast in the blackness, exchanging vicious roars in the process.

The air was throbbing with sounds from machines gobbling up the sparkling white treasure at one end and carrying it to another. The hum of exhaust fans also added to the noise as one did its best to pull fumes upward to the surface while another pumped fresh air back down.

Aiming my small flashlight at an adjacent wall of pure salt, I watched it glimmer beneath a coating of charcoal gray. Harry went over and scratched where my light was shining, the mark turned white.

“We’re surrounded by salt, bottom, sides and top,” he said, pointing toward two large pillars that stretched from floor to ceiling. “We leave those for reinforcement. They help to hold up the ceiling. You know, keep it off our backs.”

At the deepest point, lighting was vastly improved. The behemoth vehicles screeched so you couldn’t hear anything else and the fume-salt dust was thicker than ever. The plastic safety glasses, which I’d taken off momentarily for a photograph, found their way back instantly when my eyes began to burn.

We watched as some kind of long-necked machine hoisted a man to the ceiling of a cathedral-sized shaft where he stood in a small bucket-like arrangement and flailed away at massive salt chunks that clung to the roof.

Several sofa-sized pieces dislodged and came crashing down making a “kaapoooomph” when they hit the ground.

Harry saw my mouth agape and laughed. “He’s called a scaler. That’s one of the scarier jobs down here,” he said. “Believe me, it takes your breath when a chunk the size of this jeep comes loose and goes flashing past you.”

At the bottom I also met yet another Mike, a 30-year-old, third generation miner whose grandfather and father had labored in the Avery Island tunnels. Mike Meyer…pronounced My-ahh…was a Cajun, like most of the miners.

He told me there were several third generation miners at International Salt. “It’s a safe place, really,” he said. “We haven’t had a single lost-time accident in more than a year. That’s some kinda national record of something.”

In all, we spent an hour in the shafts, returning to the welcome aroma of Louisiana mud and a cool breeze. Looking down, we were covered in a fine white powder, we didn’t have to sample it to identify.

NEW ORLEANS, La. — There has thrived within me, and inside a great many others I suspect, the urge to find another going through life with the same name,

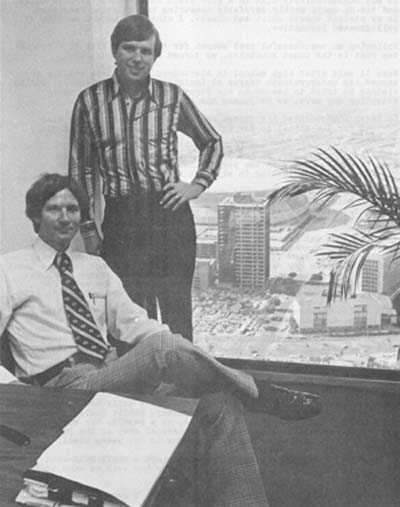

In our travels, I have routinely checked the phone directory under “M” for another critter with the less than-ordinary brand of Mike Masterson and it was here, only a few blocks from the French Quarter, I cornered one whom I shall hereafter refer to as Mike II, since I’m eight months older.

The story began when I opened the New Orleans white pages and read in tiny letters, Mike Masterson, attorney, near the bottom of the page.

Our phone conversation went something like this:

“Hello.”

“Hi, is this Mike Masterson?”

“Yes, it is.”

“Well, Mike, you might not believe it, but this is Mike Masterson, too.”

“Alright, what kind of joke is this?”

As we talked, I learned Mike II was a native of Alexandria, Louisiana, who had graduated from high school when I did. Like me, he had always wanted to pilot a jet plane and occasionally enjoyed a round of golf.

But there were a lot of differences, too. For instance, his father is a practicing OB-GYN doctor in Alexandria, while mine’s a retired Army officer. He is single and I have Kathy and Brandon, with another baking in the oven.

Mike II has an apartment several miles from his job with a long-named law firm on the 46th floor of the spiraling, ivory-colored One Shell Square building downtown.

He was as excited as I was about discovering each other. We agreed to meet for lunch the next noon at a small French cafe called Faux Pas across from his office.

The following day, before meeting face to face, Kathy couldn’t resist hopping the elevator to his office and casually asking the receptionist for “Mike Masterson, please, tell him Mrs. Mike Masterson needs to see him immediately.”

The young, attractive girl did a classic double-take then rang for Mike II as a Cheshire grin spread from ear to ear.

When you meet another with your name, the reaction is a lot like the experience when your brother or sister was born. There’s a definite feeling of kinship. Although you might know nothing about each other, you just want it to be that way.

The sizing up and comparisons begin immediately.

At first, Mike II and I looked at each other and laughed, then looked again and laughed some more. We talked about our disbelief of the whole experience. Then, as the minutes passed, we caught ourselves each watching the other, wondering what the other one’s life is like.

Mike II and I were the same height and age. We both had brown hair and blue eyes. But we really didn’t look much alike. Different than my grapefruit-like cheeks, his were more like apricots and his mouth was little where mine rivals a gravel pit I used to fish back in Arkansas.

He was conservatively clad in a gray plaid business suit, white shirt and tie. He spoke softly, carefully measuring and weighing each word. In my striped sports shirt and slacks, I clattered on and on like a well-greased locomotive.

Following an unsuccessful oral search for the possibility of a common taproot in the Ozark Mountains, we turned to comparing notes.

Mike II said after high school in Alexandria, he went to college and earned his undergraduate degree at Louisiana State University. During Vietnam he tried to become an Air Force jet pilot but they weren’t accepting any more, so he joined the Air Force Reserves.

He later disappointed his father by not entering medicine, opting instead for law school in New Orleans after friends convinced him to become a lawyer.

After passing the Bar, he had joined the insurance law firm and had been there for more than two years. He said he liked the work, even though he was putting in six days and 60 or so hours a week.

There were 12 attorneys in the Hammett, Leake, Hulse and Nelson firm. Mike II said it was small by comparison. “There’s one firm just down the hall that has 60 attorneys,” he said. “But that’s too big. Talk about office politics, whew…12 is just right.”

I asked if he was aware of political corruption in New Orleans. He sat back in his chair as the waitress served his sandwich and our salads. “Oh, I know it happens. We all know it goes on everywhere. But I don’t have any contact with it in my job. I’m not into the local political mainstream and I don’t really want to be. There are a lot of attorneys who need to be questioned by guys like yourself. Of course, that goes back to the necessity of a free press, doesn’t it?”

“But I also believe those things are not enough to bring a nation to its knees, any country and especially not this one.”

“We’ll never do away with the graft and self-seekers. That stuff will fluctuate on a sliding scale between one and ten forever.”

Where Mike II used one to ten to describe his measure of public service morality and integrity, I have lately developed my own scale from black to white with about 15 shades of gray in between.

In essence, Mike II was saying that today, with daily media revelations about misdeeds in government and bureaucracy, public indignation has fostered moves toward housecleaning and, as a result, the scale has lightened about three shades from the charcoal gray of the past decade…but it could always slide back even darker in the years ahead.

“It’s with us everyday,” he said chomping out a small half-moon from his cheeseburger, “and we all determine how much we want to live with.”

He chewed thoughtfully for a full minute after I asked if held considered going into criminal law.

“I honestly don’t have any desire to do that,” he said. “It’s one thing when you’re assigned to save money for an insurance company and quite another when a person’s life or future is at stake. I don’t want that responsibility, someone else can have it.”

“Right now,” he continued, “when the court assigns us a welfare criminal case we plead incompetence to handle the case. You have to stay up on criminal law and the many changes. If you don’t you are incompetent to defend some poor person.”

I knew about the dreams of one Mike Masterson, but what of those inside those seated across from me.

“To be a good attorney, the best, I suppose. And, like everyone else, to be happy in my work and my life. I’d like to build a nice home one day, but I’m pretty content right now.”

As for romance, Mike II has been steadily dating a woman for two years. Her father is an executive with the Mutual of New York Insurance Company which isn’t a client of his law firm.

“Who knows the future,” he said, grinning. “I know I enjoy being with her.” I said that answer sounded typically political for a novice.

After lunch we returned to his office where he delighted in telling everyone around that I was Mike Masterson. They all laughed and stared. I flushed a little and couldn’t think of anything to say except hello.

From his carpeted cubbyhole in one corner of the modern office, I looked down through a wall-sized plate glass at the top of the Superdome. His office was comfortable and I secretly imagined myself sitting behind his desk. Afterall, I was Mike Masterson, too.

But I suppose sometime that day he had fantasized himself roaming across America, talking with a thousand different people.

Afterwards, driving back to the motel, Kathy said Mike II and I should have lunch again in 40 years before our lives ended and compare notes about where we had been in our lifetimes, what we had seen and what it all had meant to each of us.

I said it was a good idea, but at that moment I wanted to head for Bourbon Street and rub shoulders with a few raw oysters and some crusty characters.

The Docks, New Orleans — Resting on the edge of a wooden dock, we watched two loaded freighters with foreign flags race to the Mississippi River bridge. Coded blasts from their horns kept each Captain abreast of the other and what his next move would be.

For 20 minutes, Kathy and I had sat in silence, studying the ocean-going vessels as they made their ways up and down the sprawling, muddy river.

Along the length of this journey, from ports in Norfolk to Seattle, we have been continually taken by the majesty and grace of the big ships…their strange oily smells, overwhelming size and the realization they will soon be out romping amid the rolling green pastures in a world all their own.

We stood and brushed off our pants then walked toward a red and black freighter being loaded farther down the dock. Drawing closer, I could read the name emblazoned in black paint across her stern…”The Manila Bataan.”

Four small, olive-skinned men with broad smiles hung across the railing on board the ship. They waved as we strolled past.

Floating cranes attached to a riverside construction raft were lifting machinery and wooden boxes high into the air then down into the ship’s empty stomach.

The crewmen followed us with their eyes while talking to themselves in an unfamiliar language. Finally, I couldn’t take it anymore. “Say,” I said, pointing my nose toward them, “do you suppose we could come on board?”

“Sure, you bet,” the tallest man answered. “Come on up the walk. I’ll show you our ship.” Once on the metal deck, the man introduced himself as Gilbert Konoshiro, a sailor who was taking advantage of three lazy days while American longshoremen stuffed the 600-foot ship.

Gilbert explained how he is at sea for about ten months every year. They were scheduled to leave later that afternoon if the cargo was loaded on time.

From New Orleans, he said they would go to Galveston, Texas, then Corpus Christi, through the Panama Canal and on to Los Angeles and San Francisco before returning home with a full hold.

The slender Filipino, whom I judged to be about five-foot, eight, said he was 27 and unmarried. “I don’t mind not having a wife and kids. This kind of life is better for now,” he said in broken English.

I wondered where he learned our language. He said English is required in Philippine schools. “We all can speak it.”

He motioned for us to follow him down a narrow passage to a small room where several men in work clothes were huddled in the corner of a long table. “This,” he said, “is the crews’ mess hall, where we eat.”

Playing cards were tucked securely in each man’s hand and the only light was from an open porthole above their heads. They looked up when we entered. Gilbert rattled off a phrase I judged to be our introduction and they smiled and waved and shrugged their shoulders then returned to concentrating on the game. “There are 35 crew members,” he said. “Most will be back on the ship within an hour.”

From the mess, Gilbert led us down another gleaming passageway to the ship’s galley where I met a frail man named Koho who was toiling over the contents of two metal pans.

Glancing inside one, I saw rice and vegetables steaming. The other contained what looked like fish. “Dinner,” Koho said, waving a wooden spoon in the air. “For the crew tonight, you see?”

I was becoming convinced the Filipinos had to be the happiest people in the world for they were always smiling. Koho the cook was no exception.

He jabbed his spoon into the concoction and held it to my lips. “You like?” Cautiously, I took it inside my mouth and rolled it around a few times before swallowing. “Ummmmm, mmmmm, Koho, that’s great stuff.” His smile stretched until I thought the edges of his mouth would meet on top of a balding head.

From Koho’s lair, we ventured down four stories into the freighter’s heart, down where the metallic machines throbbed and hissed, where it became very warm and hundreds of glass-eyed gauges watched our every move.

It reeked of oil and the fumes of spent fuel. Even the slender steel hand rails on the steep stairs were coated with a thin film of grease that stuck to our hands.

At the lowest level, five floors below deck, growling generators almost drowned out his voice as he introduced me to his working companion, Taki, who was standing at a counter jammed with equipment.

“This,” Gilbert screamed, “is the noisiest place in ship when we are underway.”

“Yes,” I bellowed back in his ear. “I believe you’re right.”

Climbing back up, Gilbert led us to his small cabin where he and a roommate named Kenata lived. The space wasn’t any larger than an average bathroom. They slept in bunk beds equipped with sideboards to keep them from falling out when the weather grew rough. The room was lighted by a single, bare bulb mounted in the ceiling.

There was barely enough area to stand and dress. But Gilbert seemed satisfied and quite happy. He sat in the lower bunk and asked if I’d take his picture, which I did.

Then we were off to the radio room for a minute and up to the bridge where he showed us how a brass stand mounted in the floor flashed orders to the engine room.

The apparatus was like the handle I’d seen in all the old Navy war movies. Instructions on the arm read “full ahead, ahead, ahead slow, stop, reverse and reverse full.” When the Captain or quartermaster wanted to shift gears, he moved the handle which sounded a bell and alerted the engine room.

Back out on the deck, we watched longshoremen working five stories down in the hold, rearranging cargo to get it balanced. The crane’s long, metal finger was still lifting and lowering crates.

“That’s ammunition down there,” Gilbert pointed to stacks of wooden boxes shoved into a corner. “They are bullets for guns to help the government in Manila. There is trouble at home now. We have Martial Law for everyone. It’s not a very good time to be there.”

Resting together on a stack of lumber, we talked a while about his life as a seaman. He said held finished school in a small town near Manila about ten years ago. Afterwards, he worked in a store and on a farm before deciding to sign on a ship. His parents didn’t want him to leave, but he told them it was time for him to make a life for himself.

The Manila Bataan was the third ship Gilbert had worked on. He was now earning $125 a month which is roughly equivalent to $1,000 in Philippine money. “American money is worth much more,” he said. “In my country, work is hard to find and many people will work for $20 a month just to have a job. Many maids over there earn only $5 a week.”

His plan was to stay on the ship until he was 30. “Then I will go home and stay. Maybe I’ll think about marriage at that time. We get very lonely and bored on the ship sometimes, but you soon learn to be alone with your thoughts. I think that is good for everyone.”

Bouncing back on his feet, he asked us to follow again. We climbed to the second level and went to a closed door next to an immaculate room containing a long dining table covered by spotless white linen.

Gilbert rapped at the door and a smallish man answered. “This is Captain,” he said proudly, “Captain Abraham Ma Luspo.”

We shook hands and he invited us next door into the adjoining room. It was, he told me, the Captain’s lounge for special occasions and entertainment.

During the next hour of conversation I learned more about the Philippine Islands and their Martial law from Captain Luspo. He believed government control of the people and even the press was best for their country. “We don’t have a free press,” he said, “and it’s best that way since we have many revolutionaries and trouble makers in our country.”

I had disagreed on that point, adding I couldn’t see how propaganda in favor of truth could benefit any nation, no matter how much turmoil there might be.

“Ahhh, but you don’t understand,” he said. “The Muslims, if they don’t like you over there, they just kill you. It’s very bad and it has to be controlled. Personally, I favor a controlled press.”

In another surprise, Captain Luspo also said he, and many other Filipinos, believe Richard M. Nixon will someday be considered one of the greatest Presidents our country has ever had. I asked why?

“Because I believe history will show his accomplishments will far outweigh Watergate…the relations with China, the ending of Vietnam and other things he did.”

“Right now,” he continued, “he is an outcast in your society, which is nothing more than an emotional reaction to a revelation of something that everyone of your leaders has been doing for many years. Actually, he was a good president.”

I probably could have settled into one of the cabins and gone to work aboard the Manila Bataan, but a long blast from the ship’s horn told Captain Luspo his ship was almost loaded and making ready to get underway.

So we wished the Captain good luck and headed for the gangplank. Gilbert was there with a paper sack. He shoved it in my arms.

I looked inside and saw it contained two bottles of cold Philippine beer.

“Just something for you,” he said. “Be sure to drink it on the dock, before you get back to your car.” I dug to the bottom of my jeans pocket and retrieved a shiny half-dollar.

“And I’d like you to have this to remember us by,” I said laying it in his palm. “Who knows you might run into a situation where you really need it one day.”

A hundred yards later, we turned and waved at each other, then he vanished below deck to get ready for leaving.

We sat back down on the dock and opened our gift, then watched for 15 minutes until the Manila Bataan set free her lines and motored out around a wide bend in the Mississippi.

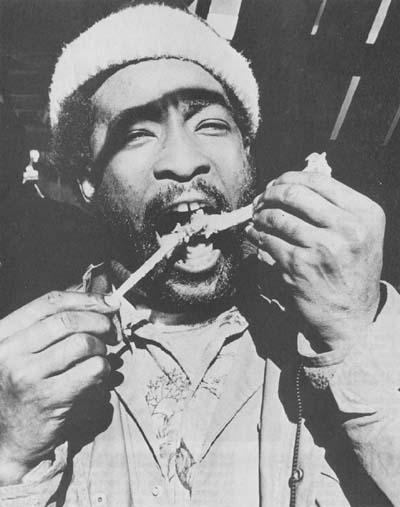

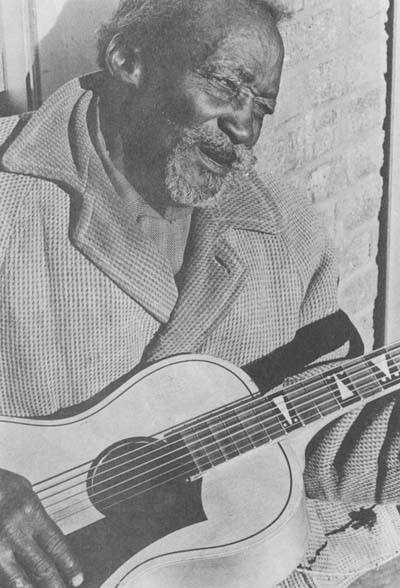

Another lesson indicative of life in America today came from this street singer in New Orleans, who threatened to beat a journalist up for only dropping 50 cents into his hat. “What do you mean only leaving 50 cents. That ain’t nothing…you hear me…nothing at all. You better get on down the street, you hear. I’ll whip you with this guitar if you don’t.” And he wasn’t smiling.

Received in New York on February 10, 1977

©1977 Mike Masterson

Mike Masterson is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Sentinel Record (Hot Springs, Arkansas). Mr. Masterson will travel throughout the U.S. with his family and write about the country and its people in 1976. This article may be published with credit to The Sentinel Record and to Mr. Masterson as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.