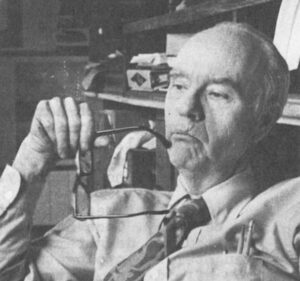

S.D. Courville is anything but a militant. He’s a furniture salesman, a fiddler, and a Cajun, but he’s not a militant.

Yet, a southern Louisiana movement that borders on militancy makes him feel good about who he La. For the first time in his 70 years People outside his “home country” are applauding his music. And in his native region, he is encouraged to speak French; an irony in that one of his early schoolteachers punished him for speaking his mother tongue.

Courville has played his fiddle in Montreal and Washington, D.C. Last spring he toured the West Coast with other Louisiana musicians. Their guide was Mike Seeger, a noted folk song expert.

“While I was in California, I asked a professor what it was all about,” Courville said, sipping dark roast Cajun coffee at his furniture store in Eunice, La. “Why were people on the West Coast interested in my music? Why were they interested in us Cajuns?”

Courville says he was told it was part of a recent upswing in interest among many to preserve local cultures.

But the Cajun revival of southern Louisiana seems to go much deeper, indeed. A lot of people are asking themselves if, in fact, a folk culture such as the one found in southern Louisiana can be revived. Can it flourish in the last quarter of the 20th Century, alongside the mainstream American culture? Does it have a place in modern America? Can its preservation be of benefit to the rest of the country?

Whether or not S.D. Courville and the other half million Cajuns of southern Louisiana think of it as such, the Cajun folk revival is an experiment which may answer some basic questions about the future of American individuality.

The Cajun folk culture already has disproven the “American melting pot” theory. After all, the culture has existed in southern Louisiana for over 200 years and although 20th Century America has made some dents, the Cajun culture has persisted.

But what about the almost militant revival of the culture? What about the bumper stickers that proclaim “Cajun Power” and another that simply says, “I eat crawfish,” a sure sign that the owner is Cajun?

Are these indications that the culture is on the defensive that it is trying hard to survive? Does the act of promoting a folk culture transform it?

And what of the Cajuns themselves? There can be no doubt that they are different from people found in mainstream America. But how different? And does their heritage and current lifestyle have anything to offer the weary refugee from mainstream America?

To know the Cajuns, one must know their history, fort unlike the Appalachians who know little about how their ancestors came to settle in the mountains, the Cajuns are quite sure. And the story is not a pretty one.

“Cajun” is a corruption of the word “Acadian,” and some say the current Cajun folk culture in Louisiana has its roots in the culture found in Nova Scotia more than 200 years ago. The majority of the Cajun people (though not all) are descendants of the Arcadians who had lived in Nova Scotia for nearly 200 years before being uprooted by the British.

The maritime provinces of Canada were settled by the French, particularly those from Normandy, beginning in the mid-1500s. But in 1713, the French-speaking people of Acadia found themselves living under the English flag. The Treaty of Utrecht, signed in that year, gave the entire Acadian Peninsula to the English. “Acadie,” the name given the peninsula by the French, became Nova Scotia, but the people were not Anglicized that easily.

The Acadians were outstanding fishermen and farmers. They were so good, in fact, that the British denied the French-speaking people the right to leave the peninsula because there would be no one left to support the British garrison with food and other supplies.

The British tried everything to eradicate the French influence. Laws were passed to force the Acadian children to be trained in the Protestant religion. Catholic priests were not allowed to officiate among them. Yet, the Acadians held to their Catholic French-speaking ways.

Many of the Acadians left their homes secretly and settled in French territory at New Brunswick it is estimated that about 6,000 left Nova Scotia between 1713 and 1755

But for those remaining, conditions grew progressively worse. The beginning of the end came in 1753 when Charles Lawrence became governor.

Lawrence was a madman. Even the English citizens of Halifax called him a “lowly crafty tyrant,” and lodged an official protest against his “wicked mind and perfidious attitude.”

As soon as Lawrence became governor, he began moving to expel the French-speaking Acadians. He did not want them to move into Canada since it would increase French strength there. His decision was to scatter them in hopes they would be dispersed and never regain strength as a culture.

On Aug. 1, 1755, Gov. Lawrence sent orders to his troops to take possession of all Acadian lands and holdings. The Acadians were ordered to assemble at their churches to hear an important proclamation. Once assembled, they were arrested and held for deportation.

Many Acadians fled into the forests and on to Canada but about 3,000 were loaded into ships without regard to family ties.

Edmund Burke wrote perhaps the most succinct assessment of the expulsion:

“We did, in my opinion, most inhumanely and upon pretenses that, in the eye of an honest man, are not worth a farthing, root out this poor, innocent, deserving people, whom our utter inability to govern, or to reconcile, gave us no sort of right to extirpate.”

The mad governor told the captains of the ships to drop the refugees along the British colonies of the Atlantic seaboard. New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, South Carolina and Georgia all received the survivors. Many died aboard ships

The Protestant colonies were not happy with the new arrivals. Many of the Acadians became indentured servants. Some were not permitted to land in the colonies or were told to leave immediately. Only Maryland, with its Catholic population, welcomed the newcomers and helped them make new lives.

The Treaty of Paris in 1763, which ended the French and Indian War, gave the surviving Acadians four options. They could return to Canada they could sail to the French colonies in the West Indies (St. Domingue, Martinique and Guadalupe), they could go to France or they could go to Louisiana, a predominantly French-speaking colony.

The records of refugee travels are few but it’s clear that sooner or later the majority of the surviving Acadians came to Louisiana. Apparently the Acadians living in Georgia and the Carolinas were the first to arrive. Some of the Acadians who originally fled to inland Canada made their way to Louisiana by retracing LaSalle’s route. Eventually the Acadians who settled in the West Indies came to Louisiana to escape the tropical climate and diseases.

Several hundred Acadians made their way to France, but they found that the French government was unwilling to help them find suitable farmlands Meanwhile in 1762, France had ceded its colony of Louisiana to Spain. These two factors brought about requests from the Acadians in France to be relocated in Louisiana. The Spanish were most happy to make the arrangements since they felt the settlement of French-speaking people in sparsely populated regions of Louisiana would be advantageous.

Thus on May 10, 1785, after 29 years of exiles the first group of Acadians left France for Louisiana. Others followed and on Dec. 17, the last shipload of Acadians arrived in New Orleans, in all about 1,600 Acadians were relocated that year.

The Spanish governor helped the settlers find new homes in the marshlands of southern Louisiana. The Spanish government spent more than $61,000 in bringing the Acadians to Louisiana and some $40,000 after they arrived. The new immigrants doubled the number of Acadians in the colony.

The period of “le grand derangement” as it is still known in Louisiana, was over but the new era when the Acadian culture was to become the Cajun cultures was just beginning.

The French “Creoles” were already firmly established in Louisiana. These original French settlers had established large plantations around New Orleans but they were French. The fact that the Acadians left France for Louisiana-indicates there were major differences between the French and the Acadians.

The weary bands of wanderers settled to the south and west of New Orleans, in lands previously inhabited only by Indians. One of the major Acadian strongholds was St. Martinville on the Bayou Teche, a place still held almost sacred to the descendants of the Acadians.

It was in St. Martinville, according to tradition, that Evangeline, the heroine of the Longfellow poem about the plight of the Acadians, was reunited with her lover. Her real name was Emmeline Labiche and she is buried in the graveyard of St. Martin of Tours Church in the town. Nearby is the Evangeline Oak where Emmeline and her lover Louis Arcenaux were reunited. The live oak on the legendary bayou is a hallowed place to the Cajuns.

Almost as if they had never suffered the terrors of a genocidal maniacs the Acadians began picking up the pieces of their agrarian culture. They planted deep roots in the rich soil of the Louisiana lowlands. They learned new methods of farming the land rapidly. From the Indians the Acadians learned how to hunt, trap and fish the waters of the Gulf of Mexico and the bayous.

The Acadians were separated from the urban influences of New Orleans by the great Atchafalaya River basin, a menacing swamp that is 40 miles wide in places. Even today the swamp is uncharted and stories of hunters and fishermen lost in the wilderness swamp are numerous.

The Atchafalaya swamp to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south and the virgin territory to the north and west provided barriers to the outside world. Slowly but surely, the self-supporting Acadians developed the Cajun folk culture in the same sort of vacuum that has produced such folk cultures around the world.

The Cajuns developed their own foods, music and customs. From these traditions came attitudes, ways of looking at life and patterns of reaction that continue today,

From the Africans they learned the art of making gumbo, a stew thickened with okra. From the Indians, they learned how to harvest fish and crustaceans from the gulf and the bayous. They learned to catch and eat crawfish the cousin of the much larger lobsters they had consumed in Nova Scotia.

They learned modern methods of rice growing from the Germans. Germans from the Midwest began settling in southern Louisiana during the middle of the 19th Century. They brought with them new agricultural skills and were welcomed by the Cajuns.

Oddly enough, most of the Germans were absorbed into the Cajun culture. Today there are numerous families with German surnames that speak French and hold Cajun traditions. The same holds true for families that immigrated from Eastern Europe’s Scotland, Ireland, England, Spain and France. It’s not unusual for a McGhee or a Schmidt to claim French as his or her mother tongue.

In his book “The Deep South States” Neal Peirce says of the Cajuns, “They seem to absorb everybody long in contact with them-a dominant gene among ethnic groups one might say.”

Of course the language is one of the most binding forces among the Cajuns as unbelievable as it may seem, a full one third of the people in Louisiana know or understand French. Most of these people also consider themselves Cajuns and live in the 21 parishes in south central Louisiana.

In St. Martin parish, for example, 25,000 of the 32,000 inhabitants — 79.1 percent — consider French their “mother tongue.” Even in the most urban of the Cajun parishes (Lafayette), 57,000 of 109,O00 people — 52.1 percent — consider French their first languages according to the 1970 census.

The French language persists despite deliberate efforts in the first half of this century to eradicate its use.

Courville, who was born north of Eunice in a Cajun farming community, says that he spoke no English when he entered school.

“I learned to read English in the first grade, but I didn’t begin understanding it until the second grade,” he says. “The professor wouldn’t allow us to speak French, my native languages on the school grounds. He would punish us if we did.”

Nearly every Cajun over 50 years old has a similar story to tell. Apparently the thought among early educators was to eradicate the culture by eradicating the languages thereby bringing the Cajuns into mainstream America.

The Acadians brought their Catholic religion with them to southern Louisiana. Today Catholicism remains predominant. Some commentators on the Cajun culture, in fact, claim that every true Cajun is a Catholic.

Cajun music is of such a distinctive nature; it is an integral part of the culture. Apparently the Acadians brought with them many ballads in the old French style. They also brought violins (called fiddles by most Cajuns) because they were easy to carry.

Early Cajun bands consisted of a violin or two and a triangle. The Germans brought an early model of the accordions it was incorporated into the Cajun band about the turn of the century. Finally, the country and western influence brought the guitar.

Today’s “traditional” Cajun band contains a fiddle and accordion what is a copy of those early models of a guitar and a triangle.

The accordion is played in an unusual staccato fashion, making it as much a percussion instrument as a reed instrument. The Cajun fiddler draws his notes out in a long plaintive wail. The triangle and guitar beat the rhythm.

Courville, a fiddler in the old tradition, learned his music from his father. He neither reads music nor understands musical theory. He plays by ear like nearly all Cajun musicians.

The songs they play can be divided into two categories. First, there are the waltzes, played slowly and passionately. Then there are the up-tempo tunes called “two steps.” The latter derive their name from a Cajun dance done to the tunes. Many have likened the jig to an Apache war dance but those who have studied the evolution of the culture say it is a traditional dances related to similar dances in other folk cultures.

Every good Cajun dances and most good Cajuns like Cajun music though none of them prefer a steady diet of it. Even today, the traditional Saturday night “fais do do” is a common event in Cajun country. The community dance gets its name from the words spoken by mothers when trying to get their children to sleep. Before the days of babysitting children were brought to the dances. The “lullaby words” the mothers chanted gave the dance its name.

Other types of community get-togethers are common, although not so common as when the culture was isolated. One is “la boucherie,” a weekend event at which a hog was slaughtered by one member of the community and the meat divided among all, in former days, a hog was slaughtered every weekend during the fall and winter months. And since a lack of refrigeration prevented meat from being stored in the sub-tropical climate, it was divided among the whole community.

“La boucherie” is still celebrated by many families but the refrigerator has taken it out of the realm of a necessity and placed it in the realm of tradition, a romanticism of the actual event.

Perhaps the strangest of all Cajun customs occurs on Fat Tuesday (Mardi Gras) prior to Ash Wednesday, the beginning of Lent.

Unlike the Creoles of New Orleans, many Cajuns participate in the “running of the Mardi Grasp” a wild affair which begins early on the morning of Mardi Gras when men in the community mount horses and, led by a captain, ride through the country side collecting chickens, geese and rice from the farmers for the gumbo pot.

The men are masked and as they ride into the farmyard the farmer, generally asks who they are. Tradition dictates the masked riders reply, “We are Englishmen” an obvious slap at the British who forced them from their homes 200 years ago.

As the gumbo ingredients are collected, they are taken back to town. About mid-afternoon, the riders return to town to join in the gumbo feast and dance. The street party goes on until dawn when the sober Lenten season begins with Ash Wednesday.

If there is one characteristic that is clear to outsiders, it is the Cajun “joie de vivre.” In fact, some claim this forms the basis of the Cajun ethics “Laissez les bons temps rouler,” or “Let the good times roll,” is a phrase most often heard at Cajun gatherings. The fun-loving nature of the culture seems out of step with the pathetic trek of the Acadians from their homeland to the lowlands of Louisiana. But, too, it shows how far the Cajun culture is removed from the original Acadian culture from which the Cajun culture was derived.

Some claim that the Cajun culture is a direct descendant of the Acadian culture of the Acadian peninsula. But, except for the fact that a few basic cultural traits were inherited from those ill-fated Acadians, the Cajun culture of southern Louisiana is as different from today’s French-Canadian culture as it is from the culture of Paris or New Orleans.

Like every other folk culture in Americas the Cajun culture has been no match for mainstream America. Thus, the culture has been endangered by accouterments of modern America, particularly mass communication and the “mobile society.”

“It was nearly lost before anyone thought about saving it,” says one promoter of the culture. “But even with all the activity of late, we still may be too late. It’s a tough fight when the opponent is mass culture.”

That’s why some aspects of the cultural preservation have taken on an immediacy, which tends to make it seem to be a militant movement. Tempers flare occasionally, as those attempting to preserve the Cajun culture look horns with those who yearn to see the people of southern Louisiana brought into mainstream American culture.

It’s a fight that began less than a decade ago. But even at that, the preservation and promotion activities may have come three decades too late.”

Only time will tell whether the preservation activities will be successful. Meanwhile, the cry of the Cajun is heard in the land. And the cry is “Lache pas la patate.”

Literally translated, it means, “Don’t let go of the potato.” But freely translated, every good Cajun knows it means, “Hang in there, baby.”

Received in New York on November 5, 1975.

©1975 Dave Peyton

Dave Peyton is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Huntington Advertiser (West Virginia). This article may be published with credit to Mr. Peyton, The Huntington Advertiser, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.