“And these signs shall follow them that believe; In my name they shall cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues; they shall take up serpents and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick and they shall recover.”

St. Mark 16:17,18 (KJV)

It is a sultry mid-July evening on Camp Creek in rural Boone County, W.Va. It is Sunday, a day of rest, and all along the tributary of the Little Coal River, families are recovering from the traditional Sunday feast.

Many have spent the afternoon on front porches, chatting with friends and relatives. Some will remain there well into the night to catch the cool evening breezes, which seem to tumble down the steep mountains, bringing a respite from the day’s heat.

Others will move inside to watch their favorite Sunday TV shows and prepare for the Monday workday. Some will gather their families in cars for Sunday evening services at one of the many small churches that dot the hilly landscape.

Among the latter is a handful of worshippers who make their way to a small frame church on Camp Creek Road where a few believers will put their lives on the line for a God who is as real to them as the evening mists that rise from the hollow.

They are the Jesus Only people, a small band of worshippers who feel they are led by God’s spirit to handle poisonous reptiles – rattlesnakes and copperheads – as part of their religious services.

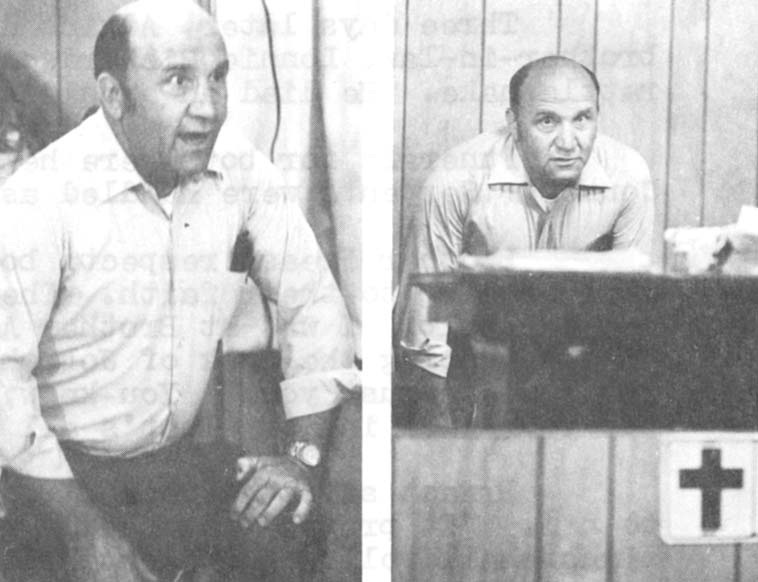

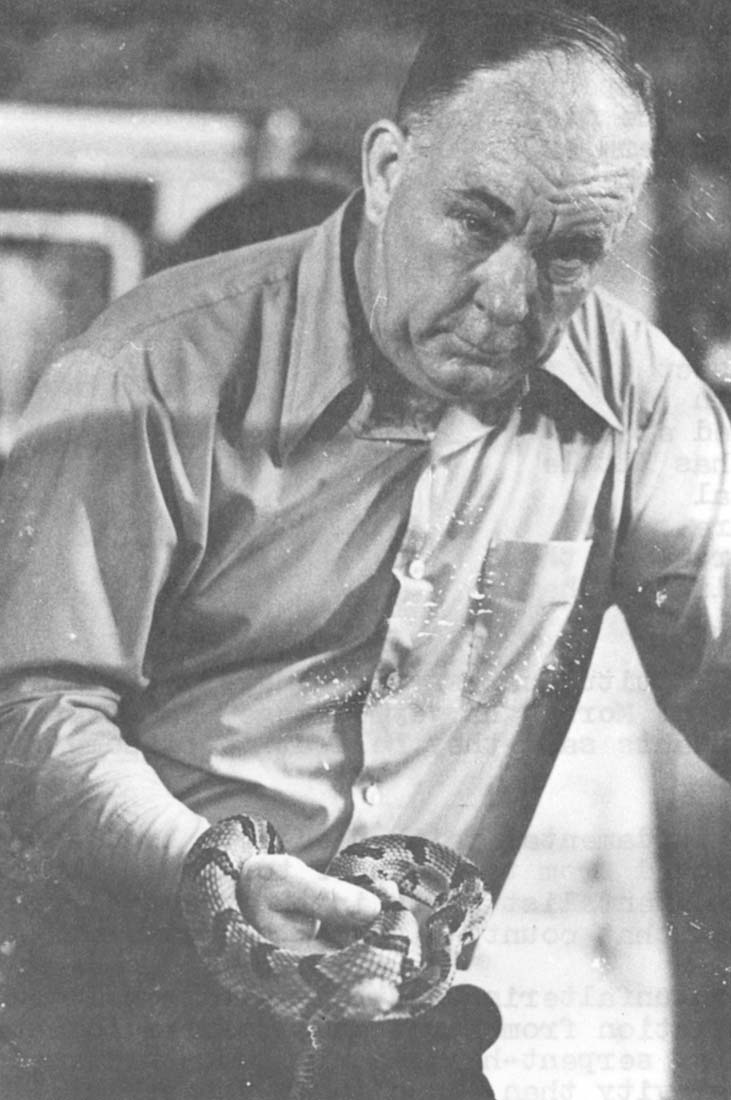

Leader of the Camp Creek Jesus Only Church is the Rev. Joe Turner, a former coal miner now disabled by black lung disease, which afflicts so many older miners in this region.

“Brother Turner,” as he is known to the believers, is a burly man; his hands calloused by years of hard labor in the mines. His disease makes it difficult for him to climb the concrete steps from the roadway to the church that sits on a bench hewn out of the mountain rock and soil.

With him is his wife who carries two small wooden boxes. Inside are the serpents – two rattlesnakes paired in one box and a small but menacingly coiled copperhead in the other.

Sister Turner carries the boxes down the red-carpeted aisle of the church to the altar while Brother Turner busies himself preparing for the service.

There are greetings all around as believers hug and kiss one another, heeding an admonition from St. Paul who told Christians to “greet each other with a holy kiss.”

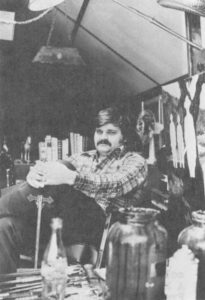

Two speaker columns, part of an extensive public address system, loom above the altar and pulpits. They are connected to four microphones and a guitar amplifier. The guitarist, a young man barely out of his teens, tunes his instrument in one corner. In another, a young lady plays the musical scale on an accordion.

Eventually, the church is half-filled. Most are believers since Sunday night services are rarely invaded by the curious spectators or “sinner people,” as believers call them.

On Friday nights, the other night for services at the Camp Creek church, it’s usually a different matter. The church generally is packed. Since Boone County offers few recreational activities, the Camp Creek Jesus Only Church is a popular place for boys to take their Friday night dates.

That Sunday evening, however, the church is filled predominantly with believers. Brother Ed Miller has driven nearly a hundred miles from his home in Fayette County, W.Va. Others have driven as many as 50 miles over the state’s winding roads to join in the service. The Rev. Elza 0. Preast, whom many believers regard as the overseer of serpent-handling churches in West Virginia, is absent. The resident of Gauley Bridge has taken his children to King’s Island, an amusement park north of Cincinnati, Ohio.

Some of the congregation that Sunday have come for healing. Others have come to experience what they say is the ultimate joy found in communing with the “Holy Ghost.” But the occasional hisses from the rattlesnakes in the wooden box are a constant reminder of the potential death that hovers about the room.

The service begins shortly before dark.

Despite four electric fans, the heat is intense. The music is deafening. Amplified guitar and voices assault the brain. The sound rattles the windows of the tiny church.

“I’m a soldier in the army of the Lord,” the believers sing, repeating the phrase again and again. Occasionally the chant changes slightly:

“If I sing, let me sing in the army of the Lord,

“If I preach, let me preach in the army of the Lord.

“If I die, let me die in the army of the Lord.”

The music ends for the moment as Brother Turner takes the microphone. His soft tones are a comfort to those who never have attended such a service. He welcomes all strangers. He tells those with cameras to feel free to take pictures. Pictures are a testimony to the power of God, he says. The congregation seconds his statements with an “amen.”

The music ends for the moment as Brother Turner takes the microphone. His soft tones are a comfort to those who never have attended such a service. He welcomes all strangers. He tells those with cameras to feel free to take pictures. Pictures are a testimony to the power of God, he says. The congregation seconds his statements with an “amen.”

As he moves from introductory remarks into his sermon, his voice becomes louder, his pace quickens. The believers see in him the “anointing of the spirit.”

He talks of death and life beyond the grave. He talks about the day of Pentecost, when, the Bible says, the Holy Ghost was first revealed to man. He speaks of the mysteries revealed to those who have the spirit in them.

Brother Turner falls on his knees. He jumps in the air like an acrobat. A frenzy has overtaken his body. Often he speaks phrases, which are alien to Appalachian speech patterns. This, the believers know, is the “unknown tongue” of the Holy Ghost, who is speaking through the brother.

Turner’s face reddens. The veins in his neck bulge and throb. He pants uncontrollably as the believers urge him onward with shouts of “amen” and “Help him, Jesus.”

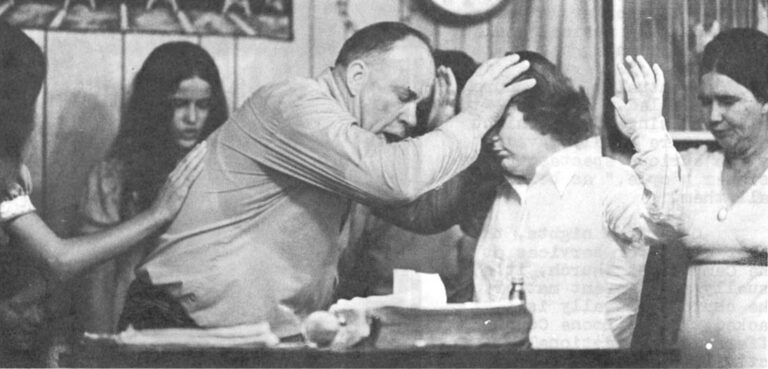

Finally, the flood subsides. He finishes his sermon and calls for prayer from the congregation. The believers fall on their knees in front of their pews and shout their individual prayers to Heaven. Some cry. Others chant in the unknown tongue. Still others seem near ecstasy as they lift their hands toward the sky, their arms and upper torsos jerking.

The prayers end. The believers grow silent again. Brother Turner paces uneasily back and forth behind the pulpit, occasionally glancing at the wooden boxes with their deadly contents. He holds his left hand above his head and points to its withered appearance.

“A rattlesnake got me on this hand about two years ago, right here in this church,” he says. “It hasn’t been the same since.”

“A few minutes after I got bit, I couldn’t stand up any more, I went to the back of the church and laid down in a pew, but I was too hot to stay inside, so I went outside and laid down on the concrete. Then I passed out.”

Brother Turner believes he was close to death as a result of the bite.

“I stayed in one room of my house for 14 days and nights. They waited on me just like a baby. Some said I would lose that hand, but I didn’t believe a word of it. It was as black as black could ever get. About 150 people came to see me. Some of them prayed with me and some of them, I believe, couldn’t wait till I died.

“I never slept a wink for the first two days and nights. I was in so much pain. The blood ran out of the corner of my mouth and into a bucket on the floor.

“A policeman came and tried to make me go to the hospital. He flashed his light down into what looked like a gallon and a half of vomit and blood. He said ‘I believe you’re going to die.’ He said he was going to get a court order to force me to go to the hospital. I told him, as best I could, to get out of the house and never come back. The policeman came back with a doctor but I wouldn’t see either of them. I had two or three boys around and I think the boys ran them off the creek.”

Brother Turner continues with his simple philosophy, the heart of the serpent-handling belief:

“I say this. If I get bit, don’t take me to no doctor. If God can’t deliver me, let me go on home to be with Him. I believe that with all my heart. I’m not going to no doctor for snakebites. God said to do this and if you do it and He can’t take care of you, He’d be a mighty poor God.”

The sounds of the accordion, guitar and tambourines rise as Brother Turner’s testimony ends. The believers know that the time for handling serpents is at hand.

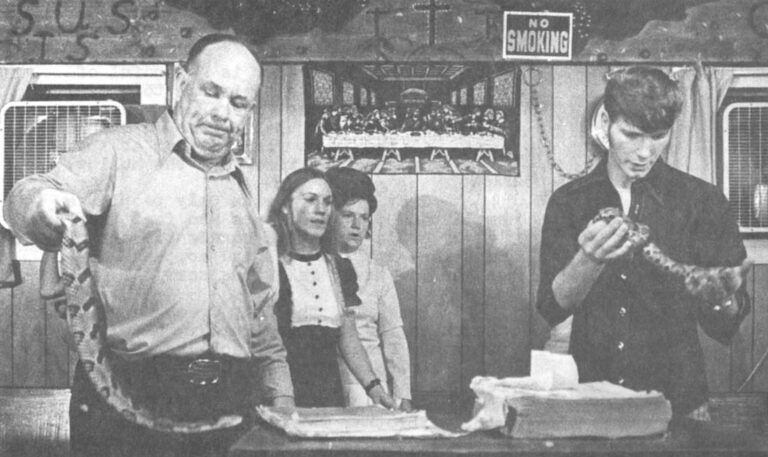

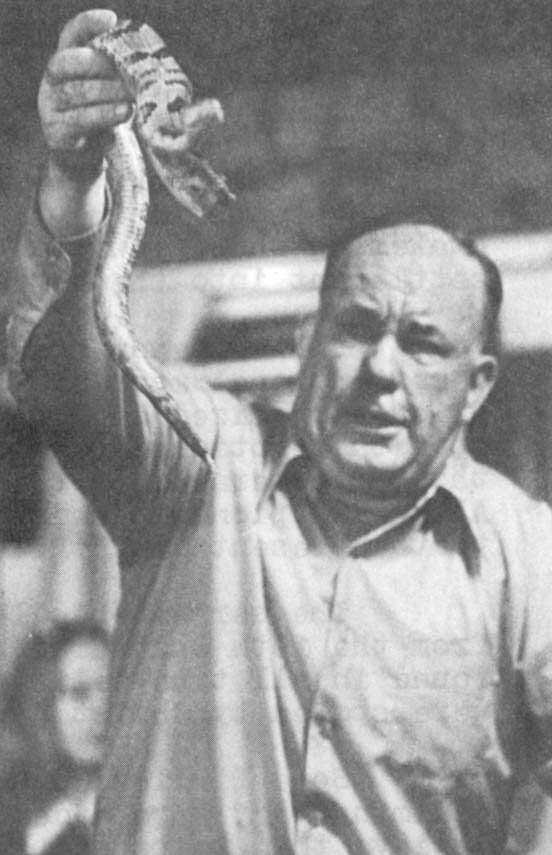

Brother Turner holds his right hand to his head. He closes his eyes and waits, in a half-crouch, for the Holy Ghost to lead him. Suddenly, as if by command, he reaches for the box containing the rattlesnake. Without hesitation he snaps open the lid and clutches both reptiles in his right hand.

He holds one by the tail while he passes the other to another believer. Brother Turner allows the snake to coil around his arm. He makes a perch with the palm of his hand. The rattler climbs to the perch and coils as if it were going to strike.

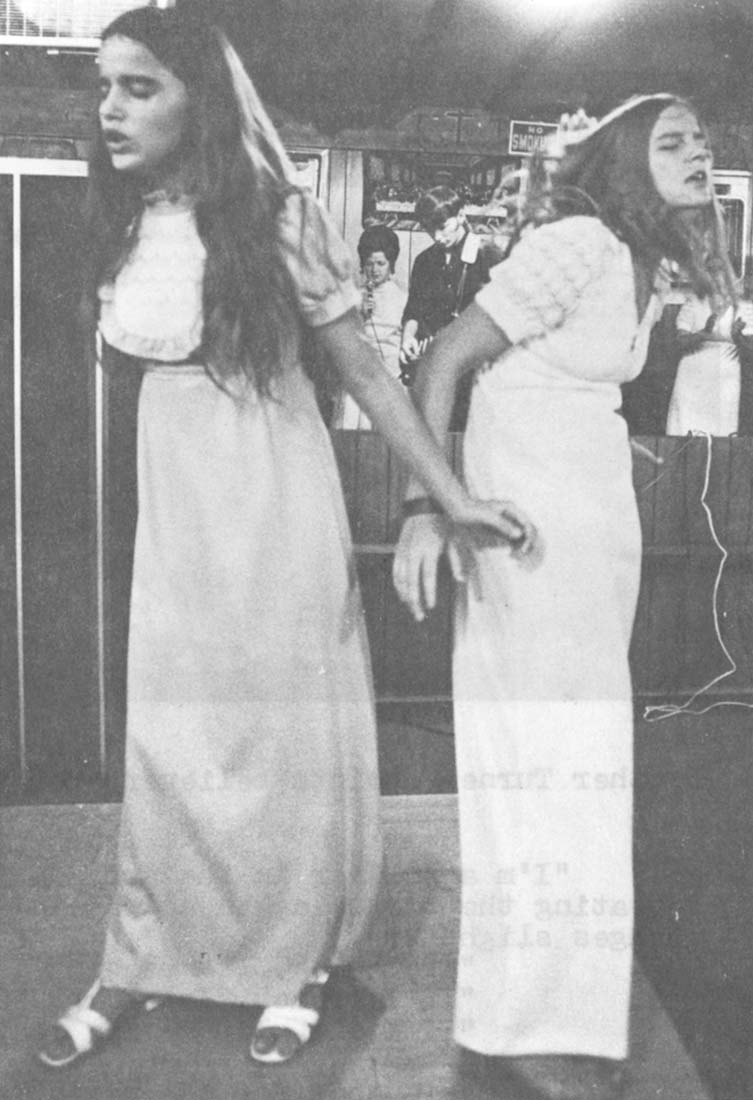

The frenzy among the believers grows. Three teen-age girls dance to the music. They scream “Jesus, Jesus, Jesus” over and over in a sort of chant. Their eyes are closed. Perspiration soaks their long hair and fashionable dresses.

Still the serpent handling continues. The guitarist puts his instrument aside. He reaches for the copperhead. Placing it on the pulpit in a coil, he waves his hand frantically a few inches above the snake’s head. The snake, perched atop an open Bible, doesn’t strike. It probes the air with its tongue but fails to take revenge.

The serpent handling lasts fewer than 15 minutes. In all, about a half dozen believers have been moved to hold the snakes that evening. As a testimony to the power of God, Brother Turner holds the larger rattler by the tail while a photographer snaps more pictures. The snake writhes, coils and jumps, but doesn’t strike.

Photos by Tim Grobe, The Herald-Dispatch Huntington, W.Va.

Finally, all three snakes are placed back in their boxes. The believers have been spared death and agony just as the 16th chapter of Mark promises.

The entire service lasts until 11 p.m. The believers go home tired but fulfilled by the events of the evening. Led by the Holy Ghost and two verses in the New Testament, they are part of a small but strong band of Appalachian fundamentalists who risk their lives in service to their God.

The serpent-handlers of Appalachia are comparatively new. The sect is believed to have started in the mountains of Kentucky and Tennessee about 1910. But the impetus for such a movement could be traced to early pioneers with their Calvinistic beliefs and their literal interpretation of the Bible.

In his book “The Allegheny Frontier,” Dr. Otis K. Rice says that the settlers who came to West Virginia were affected by the Great Awakening, whose powerful influences coincided with the advance of settlement into the mountains.

“This phenomenon shook the settlers loose from their old denominational moorings and gave rise to new and militant sects, which emphasized a close personal relationship with God and reliance upon the emotions as guides to spiritual truths. The new religious thought generated by the Great Awakening made rapid headway among Allegheny pioneers and resulted in a fundamentalism that has endured to the present day,” Rice says.

The serpent-handlers claim that the words of Christ, taken from the 16th Chapter of Mark, are a delineation of characteristics found in all true believers. According to the scripture, the words were spoken by Christ just before he ascended into Heaven.

Some Biblical scholars doubt the authenticity of the verses, claiming they were added much later. But the serpent-handlers believe them to be actual words spoken by a living God.

The sect is known as “Jesus Only” by other Holiness and Pentecostal religions in the mountains because of the serpent-handlers’ complicated belief that no trinity exists. It is not going too far to call the sect fundamentalist Unitarians. But the full knowledge of the Jesus Only movement is not revealed to nonbelievers, the serpent-handlers say. Understanding can only come when the Holy Ghost reveals it.

The Appalachian serpent-handling sect is small when compared with its related fundamentalist denominations. While no census of the believers has ever been taken, it’s generally felt that fewer than a thousand southern mountain people call themselves serpent-handlers at any one time. Turnover among the faithful in West Virginia is large.

The Rev. Elza O. Preast, the unofficial head of serpent-handlers in West Virginia, has been with the movement since 1946. He says his introduction came only a few months after it was brought into West Virginia by a Kentuckian who “used to bring his snakes on a Greyhound Bus.”

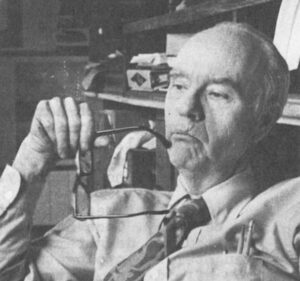

Brother Preast, 57, is owner of a trailer court near his church on Scrabble Creek in Fayette County. Until recently he ran a successful moving and storage company. He was so successful; in fact, he was able to sell the company for a considerable profit.

Preast believes that God has blessed him in his business affairs throughout his life.

Brother Preast was on hand two years ago when Brother Turner received his near-fatal bite. “I went outside where Brother Turner was laying on the ground,” Brother Preast says. “I took his cheeks in my hand and prayed ‘Jesus, rebuke this death spirit that’s on Brother Turner.’ I believe I saw a miracle that night because I believe Brother Turner came back from the edge of death.”

Preast has been bitten eight times in his 30 years with the movement. Six of the bites were from copperheads. Two were from rattlesnakes. He carries the rattlesnake fang marks on his arms.

If the believers place their trust in God, then why are they bitten?

Neither Brother Preast nor any of the sect’s members has the answer. As to the reasons for his misfortunes with snakes, Preast says that on one occasion, just before he was bitten, the Lord spoke to him and told him he shouldn’t have handled the serpents that particular night.

What about the other times? “I don’t know,” Preast says. Maybe I was mean. Maybe the Lord wanted me to do better. I don’t have the answers to all of this.”

In some instances, Preast says, he believes the Lord allows the bites to prove to the non-believers that the snakes used in the services are dangerous.

“Some people claim we sew their mouths up. Some say we milk the poison from them. Others say we drug them some way. But when a snake bites a brother or sister, that proves we won’t do anything to them doesn’t it?”

Last year was particularly disastrous for the West Virginia serpent-handlers. Three of their number died as a result of bites.

A Logan County resident died in the early spring of 1974. A few months later, Talmadge Adkins, a Wayne County resident, was bitten four times by a rattlesnake during services at Brother Preast’s church.

Three days later, Adkins died. Six weeks later, Adkins’ brother-in-law, Lonnie Richardson, was bitten on the neck by a rattlesnake. He died an agonizing death from the bite.

Funerals for both were held at a small church in rural Wayne County. Serpents were handled as part of both funeral services.

Brother Preast respects both Adkins and Richardson. “They died holding to their faith. They died trusting God and refusing medical help. I was at Brother Adkins’ bedside just before he died. He was quoting the Book of Job where it says ‘Even though you slay me, yet I will trust you.’ You know, you can’t love anything more than to put your life in it. That’s all Jesus did.”

Preast says the reason for handling serpents is crystal clear to him. “It proves that people have faith. The Bible says these signs shall follow them that believe. If I had my druthers, I’d rather that not be in the Bible. But the Holy Ghost leads me with an anointing. There are times when I wouldn’t touch serpents at all. But when the Holy Ghost anoints me to handle them, it doesn’t mean any more than handling a shoestring.”

Serpent-handlers have been the target of much persecution in the last half-century. Nearly all states in the southern mountains, except West Virginia, have enacted laws prohibiting the handling of serpents as part of religious worship. The laws are violated constantly.

In the early 1960’s, there was a move to enact similar legislation in West Virginia. Preast fought the legislation. The proposed law failed to gain legislative support.

Similar laws in other states have reached the U.S. Supreme Court. Some claim the laws would not hold up under the First Amendment guarantee of freedom of religion. A court case in Tennessee last year seems to indicate that, in fact, the sect can’t be prohibited from practicing serpent handling.

The case involved a mountain church near Newport, Tenn., where Cocke County officials had issued an injunction prohibiting the practice. The case finally reached the state’s Court of Appeals.

Writing for the majority, Justice Frank F. Drowota III said, “When a party injures, or threatens injury, only to himself and does not injure or disturb the public, his activity cannot be prohibited under a nuisance rationale… Defendants’ snake-handling constitutes a nuisance only when done in a manner in which non-participants may be endangered, and is enjoinable only to that extent.”

Preast says the record shows that no non-participants have ever been bitten at services where serpents were handled. This tends to prove, he says, that only willing participants are endangered.

“I’ve never had anyone tell me they were afraid during the service. But I have had people to tell me that they felt no fear at all, even though they were scared to death of snakes,” he says.

What of the future of serpent handling?

Some claim that the practice grows out of ignorance and that as education increases and the hollows of Appalachia are exposed to the outside world, the sect is likely to disappear. Preast disagrees.

“It says in the latter days, God will pour out his spirit upon all flesh,” Preast says. “That’s what is happening. The Holy Ghost is falling on them. Them that is saved and them that want to do right is going to get the Holy Ghost on them.”

Preast is acutely aware of the criticism about the believers. “Some say that we’re crazy. I think I’m a wise person, and I’m not saying that boastfully. I think that anybody who will humble themselves before God is wise. God is blessing His people. He’s raising them up.”

Brother Preast sees the flurry of recent newspaper and television features about the serpent-handlers as a sign that God is moving to spread the word. “I’ve never asked a newspaper reporter or photographer to come to my church and take pictures, but they come all the same. They don’t do that at any of the other churches I know,” he says.

One might expect that a church with such literal and narrow views of religion might be narrow in its outlook on righteousness. That isn’t the case. Preast says he feels people of many faiths will attain rewards after death.

“There’ll be Jews in Heaven. There’ll be Catholics in Heaven. There’ll be Baptists and Methodists and Church of God peoples. But they’ll all be people who have gotten the Holy Ghost, and, you know, the Holy Ghost reveals itself to different people in different ways.”

Instead of finding fault with others, Preast has a simple outlook about the family of man, which is refreshing and tender in this age of complications.

“Instead of belittling people, hating people, we ought to take them in, love them and give them what they need. I mean all mankind, not just a certain religious group. After all, that’s why Jesus Christ died, isn’t it? Because he loved people. He didn’t have to do that. He didn’t have to die for people who were living in sin. He died for people who we might term as nothing. And that’s the way we all were at one time. Instead of fighting people, we ought to be loving them. God is a God of love.

The small sect of serpent-handlers in relatively isolated areas of the mountains has little impact on the total Appalachian culture. Yet, it is part and parcel of the fundamentalist religion that permeates the region.

In a recent attitudinal survey of West Virginia conducted by Dr. Charles Lieble of Morris Harvey College, Charleston, about 95 per cent of the respondents said they held at least some fundamental religious views.

The act of fundamental faith needed to handle poisonous reptiles is not too far removed from the acts of total commitment needed by Kanawha County fundamentalist sects in their recent protests and acts of violence against that county’s school boards.

Guided by an unfaltering faith in a personal God who has promised them protection from harm, and, stirred to action by a few charismatic leaders, serpent handling or bomb throwing could become an act of lesser gravity than “handling a shoestring” as Brother Preast says.

Missionary efforts from more organized religions have failed in the mountains and they continue to fail today. Persecution only tends to strengthen the fundamentalist ranks. Their beliefs are rooted in frontier history. The area grew and bloomed in relative isolation.

Fundamentalist beliefs were planted by succeeding generations. The faith will not easily let go.

Received in New York on August 8, 1975

©1975 Dave Peyton

Dave Peyton is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Huntington Advertiser (West Virginia). This article may be published with credit to Mr. Peyton, The Huntington Advertiser, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.