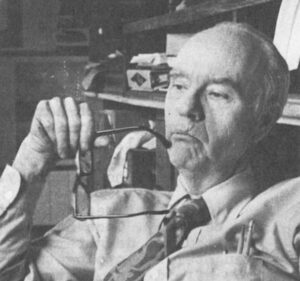

Jim Comstock, editor of The West Virginia Hillbilly, sits in the second-floor workroom of his Richwood, W. Va., offices, watching the traffic move slowly through the main street.

The line of passenger cars and pickup trucks is broken occasionally by a logging truck moving hardwood from the surrounding mountains to a mill where it will be processed for furniture or paneling.

The line of passenger cars and pickup trucks is broken occasionally by a logging truck moving hardwood from the surrounding mountains to a mill where it will be processed for furniture or paneling.

It is a sunny day in late April. The lower river valleys display spring blossoms and greenery. But in Richwood, a town of about 4,000 on the Cherry River, cold mountain air keeps most buds in their winter cocoons.

Richwood is a mountain town filled with mountain people and mountain memories. Comstock, who was born on nearby Hinkle Mountain, is the editor of a weekly newspaper that has chronicled events in West Virginia for nearly 30 years.

The Hillbilly has become a new tradition. Nearly everyone in the state has heard of it and it’s quoted often. But its sagging circulation proves more people quote it than subscribe to it.

Those who follow The Hillbilly read it primarily for the regular feature on the last page of the tabloid – an outpouring of humor, pathos and other thoughts from the mind of its editor.

Sometimes it’s simple humor such as the time the editor wrote the story of the mountain farmer and his wife who had just paid the mortgage on their small farm.

“Oh, Pa,” the wife said, “it’s just that we have all this and there’s our two daughters a-layin’ out there in the cemetery.”

The man looked sad, too, Comstock said, and just stared down at the floor.

“I know it, Ma,” he said. “And I know I oughtn’t to say it, but to tell you the truth, I’d a heap rather they was dead.”

Sometimes Comstock writes with the plainspoken beauty of a country editor. On the death of Marilyn Monroe, he wrote:

“The girl who lived across the street from us all got tired and wanted to go to bed and sleep. I hope her dreams are all nice dreams, like maybe growing up in a little town with a mother to love her and teach her, and a father to worship her, and then to find a prince charming who, after they have planned and worked together, will get her a little two-bedroom castle and a baby or two, and share with her a nice, long, uneventful life of being a very, very happy nobody.”

Sometimes the truth, according to Comstock, hurts too much to be funny. Once he told the story of another Richwood resident who visited his daughter, a schoolteacher, in another town. The daughter was apologetic because on her tight budget, she could not afford real butter. All she had was margarine.

“The fellow told her not to take it so hard,” Comstock wrote. “He said all she had to do was find somebody who was on the surplus commodity list and trade him out of his butter, because butter is one thing that the government has a lot of, and usually a family gets more than it can use and they barter a bit with their butter.”

Comstock pointed out to his readers that here was a family earning money, but doing without butter so it could pay taxes to buy butter for people who weren’t making money and therefore weren’t paying taxes.

“He laughed…telling me about it,” Comstock wrote, “and I laughed, too. And then we stopped laughing and just looked at each other, because suddenly, it wasn’t funny any more.”

Sometimes the entire last page is devoted to praising simple mountain joys. Who else but Comstock could write reams about the joys of hog slaughtering and make it sound poetic?

When Sharon Rockefeller (Mrs. John D. Rockefeller IV) came to West Virginia, Comstock devoted the last page of his newspaper to giving her friendly hints on how to be a mountain housewife.

He reminded her that “Corn dodger isn’t worth a rap without cracklins. Restaurants don’t know that, and that’s why corn dodger isn’t fit for the hounds in restaurants.”

He provided Mrs. Rockefeller with the secret for gathering the best poke greens and how to choose the best sassafras for tea. He reminded her that not all mountain people eat mountain cooking. “They’ll tell you that ‘Possum is eaten only by white trash,’ and then go off to the Greenbrier and eat snails,” he wrote.

Most of Comstock’s life has been devoted to telling about mountain life as he sees it. Unashamedly he has made fun of mountain people and the “outsiders” who come to West Virginia with missionary zeal. During the 1960 Kennedy-Humphrey presidential primary in West Virginia, he wrote about the two contenders and their use of West Virginia as a springboard to the presidency. He did it through a mythical family composed of Ma, Pa, Sis, and Fiddlin’ Clyde. Making light of some of West Virginia’s most infamous political shenanigans, he proudly proclaimed (with tongue in cheek) that Pa had decided he couldn’t bring himself to sell his vote to a Catholic.

Comstock is intense about Appalachia, although he doesn’t consider himself an expert on the people and culture (a trait which seems common among those who are best suited to be called experts).

Comstock says the old-style Appalachian culture is gone, leaving the mountains with a form of mutated Appalachian culture, not at all like the old, but still out of step with the rest of America in many, many ways.

“I grew up on Hinkle Mountain where people represented a certain subculture all their own. Well, one time an Austrian family moved in. We couldn’t help but see the difference at first. But sooner or later they became assimilated. They attended our mountain wakes. They were Catholics, but they took their kids out of Catholic schools. Why? Because of what we were, I suppose. Appalachians were like the Chinese. We eventually conquered everybody we came in contact with.”

That still holds true to a lesser extent, Comstock says. Is it because the Appalachian people are so strong, their culture so tenacious?

“No, I think it’s because the Appalachian subculture is so basically good. In Appalachia, for instance, you seldom find people who take advantage of others. You take all the big deals – taking money and going off to Switzerland. That’s not done by Appalachians,” he says.

He surveys the quiet street outside his window again. “Just recently, it was reported that there was a murderer loose. Police reported he was on his way to Richwoods. The authorities came around warning people to look their doors. Can you imagine that? People having to be told to lock their doors at night? I leave my keys in the car frequently. I never lock it at night and never in this world have I lost anything in Richwood.”

No matter how “basically good” the culture is, it’s changing, due in large measure to television, Comstock believes.

“I had a girl come here and scrub the office the other day,” he says. “Back in the old days, all one ever needed was a mop, a mop bucket, some water and soap powders. Well, my Lord, she had a list of things she needed that came to $42. And they were all brand names she knew from TV. She was speaking a strange language. Now her whole life is shaped, not by her family or the things she has heard from them, but from the tube in her living room. And she listens to commercials more than anything. And her children eat the no-good fun foods. Her corn flakes must sparkle and crackle. She has forgotten how to feed her family, if she ever knew.”

Destruction of cultural differences by mass media is widespread, Comstock believes. “All cultures are being destroyed by the media. I suspect Brooklyn has lost most of its dialect, its old customs. Portnoy’s complaint of the ages will be something else. It will be against the media.

Government runs a close second to the media in forcing change, Comstock says. If the government isn’t forcing change, it keeps the culture in an uproar so that the culture changes by degrees.

“We have government experts that come down here and study us and want to change us, make us like everybody else. Then we have more government experts come right on their heels and want us to preserve our culture.

“We’ve spent a great deal of money teaching Appalachians the arts and crafts of the old people – weaving for instance. Well, they went to Africa and found master weavers who beat anything. They could weave watertight roofs from the fronds of the palm tree. Well, the government people were absolutely shocked at that, so the government is teaching the people to use modern roofing materials. We call it civilization. At home we’re teaching people to weave who don’t know how to weave. Meanwhile, in Africa, for those who could weave and make practical use of their weaving, it wasn’t any good.”

“But you know and I know that someday the government will find the last old man or old woman among the Africans who knows how to weave. And he or she will be hired to teach the rest how to weave roofs.”

Comstock says he remembers 1960 when “(John F.) Kennedy came down here and found us a forgotten people. The idea was to change us, to get us into the mainstream. Well, now the idea is to get out of the mainstream, because we’re not sure it’s good to be in the mainstream any more.”

The leaders aren’t all to blame for the demise of the culture. The people of Appalachia have wanted to be in the mainstream. In moving in that direction, they have abandoned old ways, Comstock says.

“When I was a child, we moved to a farm. On this farm was a number of little houses and buildings. In one was an old loom. Another had bullet molds. Everything in those buildings was absolutely Smithsonian. Well, before I got to college, we had destroyed everything on the place. I made a sled out of the loom. I remember. Nobody ever told us the loom should be saved. My people were too close to it to recognize its worth. They were part of the generation that wanted to forget.

“I remember at that time my father brought home a knitting machine. He was trying to hold on to the new because he didn’t want to be old-fashioned. My mother was glad to get rid of the old ways. She was glad to get rid of that loom, glad she didn’t have to sit at it hour after hour. She was glad to have it torn up. She felt liberated.”

Comstock calls these artifacts of the old culture the “tangibles,” and in recent years, much of his works outside the newspaper profession, has been to preserve the relics of days gone by. He was instrumental in saving the Cass Scenic Railway, a narrow gauge logging train, which once carried timber out of the mountains near Richwood. Today it carries tourists to the top of some of the most spectacular mountains in the state. He was also a leading force behind the restoration of Pearl Buck’s birthplace, another popular West Virginia tourist attraction.

The editor is involved in Richwood’s annual Ramp Festival, a spring gathering devoted to a native onion-like plant that is eaten in the spring. The eating of ramps is more of a ceremony with West Virginia highlanders than it is a meal. The custom goes back two centuries.

Comstock believes that by preserving the tangibles, generations of Appalachians to come can learn about the past and perhaps be persuaded to preserve some of the cultural intangibles.

“Nobody in West Virginia should be permitted to tear anything down until somebody from the state has had a chance to check it for preservation qualities,” he says. “Over in Marlinton, for example, there’s an original toll house, a building where they used to collect tolls from those traveling over the first roads in this part of the country. No one from the state seems interested in preserving it, but in some states they’re building replicas of their old toll houses.”

He tells the story of a marble factory in Bridgeport, W. Va. “You know, West Virginia was once the Marble capitol of the world. Well, a man came up to me and said that the plant, which made the first marbles in West Virginia, was closing. He wanted to give the marble machine that made the first marbles in the state to the state government. Well, I called the Governor and pleaded with him for the state to get the machine. I called again and again. The governor wasn’t interested. Finally, the man who owned the machine said the Owens Illinois Glass Co. was giving him $5,000 for the machine. They wanted to put it in a museum, and the museum wasn’t in West Virginia.”

West Virginia garden clubs raised the money for the preservation of the Pearl Buck Birthplace. After it was purchased, the federal government gave $100,000 for its restoration.

Comstock says he sees a great deal of this lack of respect for tangibles in the young.

“A kid doesn’t respect a book any more. Because of mass production, they’re cheap. And a schoolbook means so little to a youngster. After all, most schoolbooks don’t belong to the children. They belong to the school system that purchased them. There’s no pride of ownership. And what about the hot lunch program at schools? That means there’s no pride of ‘vittles’ any more. It used to be important what you brought in your lunch. My wife used to bring cold ham on a biscuit. My Lord, there’s nothing more edible, or eatable.”

If the tangible remnants of the culture are preserved, Comstock says, they can form the basis for teaching the young about Appalachian cultures. This, he admits, is “catching on,” but not fast enough to his liking.

“I’d like to see every town in West Virginia have a little museum. A place where one could go to charge his batteries, so to speak.” But he thinks that’s unlikely, because for every person who’s aware of his cultural background, there are a hundred Appalachians still trying to live it all down.

The writer himself is part of the new wave of cultural awareness. He is constantly asked to speak before groups about Appalachian heritage. At each opportunity, Comstock impresses upon the audience the need to preserve the heritage through preservation of the old “things.”

And yet, this wave of awareness bothers him. Unlike his mother and father who simply lived in the culture without being aware of it, the modern Appalachian is being bombarded with programs designed to make him aware of his cultural heritage. Comstock believes this forces the entire culture into a very critical stage.

“If you’re aware of who you are, you start losing it or keeping it. It’s a point of no return.”

Comstock Quotes from the Hillbilly

On Appalachian Poverty: “We have eaten of the fruit that Eve did, served by the same caterer, and learned our nakedness. We didn’t know we were impoverished and underprivileged until we were told, and we took to our beds from the shock of it and had to be fed through the veins. That’s what happened to us.”

“Every day for a month old Doc Hyer had been delivering babies all over Nicholas and Webster Counties. Every time he asked the poor girl who it was it turned out to be Morty Martin. It made old Doc Hyer mad. And when the Widow Wilson had triplets and her daughter had twins, Doc hunted Morty down to have it out with him. He cussed him out for a while and then he said, ‘Great balls of fire, man, how could you do such a thing?’ Morty said shucks, it wasn’t nothing, he just got him a bicycle.”

“There’s a test for a real country editor. Ask him how long a haircut is and he will tell you it is three galley proofs long. When a country editor goes to the barber chair he stuffs his pockets full of proofs, so that if he has to wait he won’t waste time. And when he gets in the chair he still won’t waste time. He’ll read proofs and that’s why he knows that a hair cut is three galley proofs long.”

ON SPRING IN APPALACHIA: “One would never get down on paper what Spring means, that is, one whose Springs were intermeshed with a farm, a poor, hand-scrabble farm in my little corner of Appalachia. Sassafras tea comes back to me, pungent and overpowering. And poke greens, a thing at which so many people have turned their noses up, and yet which there is no delight that is gastronomiker than. And ramps, too, if one is fortunate enough to have lived in that special rich part of Appalachia. But spring, all in all, is a lurking thing in old bones, not something you write about. It is different things to different people but there are dappled chinks of it, little half-remembered sniffs of it, that make the world kin. And better. And now, let us be off, as Houseman wrote, to see the pear tree in bloom, because of our three-score years and tent there is but little room…Yes, let’s!”

“The Widow Crotchet never missed a testimonial meeting at the church near her home and she never missed a time to get up and testify her unworthiness to serve the Lord alongside the others who were more adequately prepared. She came into the house of the Lord this particular time and sat down and when most of those present had testified, she got up and told how unworthy she was. ‘I ought not to be up here with you people. I am so unworthy that I ought to be back behind the door.’ When she sat down, Brother Crookshanks got up and said; ‘I too am unworthy of the Lord’s grace and tender mercies. I orta be back there behind the door with the Widow Crotchet.'”

“It is Calvin Coolidge’s good destiny that he, who did nothing because he strove to do nothing for us, lives on in an unforgettable quote: ‘When a great number of people are not working, a state of unemployment exists. One wonders if fate might not be equally kind to President Lyndon Johnson and let him live, not by his acts alone, but by that haunting remark, ‘For the first time in history, profits are higher than ever before.'”

“Lute Farby always said in time of economic stress a man with a big family had to do a heap of thinkin’ to keep them from starvin’. What he did, he said, was pay his kids a quarter if they wouldn’t eat no supper at night and then charge them a quarter for their breakfast in the mornings.”

“The men who came in to look the land over, with an eye to making a lot of money from a coal mine, were impressed with the formation of rock strata. They said it was the prettiest thing they ever saw. Uncle Ezra Hindergast told them it was not only the prettiest, but also the oldest, because it was one billion and three years old. The mining engineer asked him how he could narrow it down like that and he told them: Dr. Price, the geologist from West Virginia University, told him it was a billion years old, he said. And it was three years ago come June that Dr. Price was here.”

Received in New York on June 9, 1975.

©1975 Dave Peyton

Dave Peyton is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Huntington Advertiser (West Virginia). This article may be published with credit to Mr. Peyton, The Huntington Advertiser, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.