Saturday night isn’t quiet in southern Louisiana.

The sounds of accordions, guitars, fiddles and triangles pierce the air from Houma to Lake Charles, from the tiny French Casino Bar at Mamou to the bigger nightclubs in and around Lafayette.

It’s Cajun music being played, a sound unlike any other folk music in America. It’s a sound apart from mainstream American culture, but there’s evidence mass culture may be ready to take Cajun music to its heart.

Like the Cajun French language, Cajun music is a strong glue that holds the folk culture together. It is a way of expressing emotion, of feeling part of the old culture, of displaying musical skills handed down from one generation to another for more than 200 years.

Not every Cajun likes Cajun music, just as not every native of Nashville, Tenn., cares for hillbilly music. But the Cajun music cult is strong despite the recent influence of modern rock and country and western.

While there are those who believe that preserving the French language will preserve the Cajun culture, others believe it is more important to preserve Cajun music, for there lies the heart and soul of the Cajun ideology.

“These young Cajuns will soon learn that the rest of America is getting tired of rock n’ roll music,” says Mark Savoy, an accordion-maker and Cajun musician from Eunice, La. “I’ve played a lot of Cajun music in the United States, Canada and South America. I’ve found people more impressed with Cajun folk music than any rock n’ roll. That means these Cajun kids who have given up their ancestral music for rock n’ roll have got a real surprise in store for them soon.”

In fact, Cajun music does seem to be making inroads into the world of pop and country and western music. The sounds of the wailing fiddle and accordion can be heard, for example, in “Acadian Driftwood,” a cut on the newest album by The Band. Written by Robbie Robertson, the song explains how the Cajuns got to Louisiana from their homeland in Canada and theorizes that, although the Cajuns continue to live in Louisiana, French-Canadian blood still courses through their veins.

Whether or not today’s Cajun culture is all that similar to the present French-Canadian culture, Cajun music is closely associated with French-Canadian folk songs of long ago.

Before the Acadians were exiled from Acadia (Nova Scotia) in the 1750s, a large and impressive group of French-Canadian folk songs had already developed. Some of them, no doubt, had their roots in France, particularly Normandy. Many of them had their origins in Acadia. And, like so many other folk songs in other folk cultures, most were sung without accompaniment.

The major musical instrument of the Acadians of Nova Scotia was the violin, or fiddle. It was played at dances and weddings and probably even at wakes. Some people, including Savoy, believe the French-speaking Acadians may have learned to love fiddle music from the Scotch-Irish who inhabited Nova Scotia before the French were cast out. There is evidence that French and Irish intermarried in the province prior to the Acadian expulsion. Perhaps the Scotch-Irish gave the French more than spouses for the short period the two cultures existed side-by-side.

With the expulsion of the Acadians by the British, much of the French influence was gone from Nova Scotia. Many of the Acadians moved into the interior of Canada. A great number of the Acadians, however, finally immigrated to Louisiana. They brought their French folk songs with them and brought their fiddles as well.

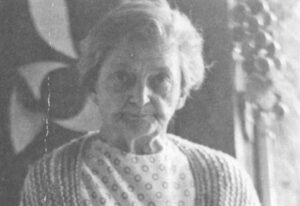

Mrs. Lloyde Neil Holmes of Lafayette, a major collector of folk music in the Cajun parishes of Louisiana, says the French folk songs are still in existence in Cajun Country but the traditional Cajun music is indigenous to Louisiana.

In her book “Louisiana-French Folk Songs,” Mrs. Holmes notes that French or French-Canadian folk songs were brought from France and Canada. They vary somewhat from the originals in music and words, but vary little in rhythm, she says. Today, few Cajuns sing these songs and they are found in few places other than music collections and in the homes of very old, very traditional French-speaking people. Cajuns do not seem to enjoy these songs as much as they do the tunes, which are native to the Cajuns of Louisiana.

The history of Cajun music begins with the fiddle. The Acadians-turned-Cajuns kept the instrument of their forebears and adapted it to their needs. In the early days of the culture in Louisiana when “country dances” at homes throughout the region were popular, two fiddles, one playing melody, and the other, harmony, were the only accompaniment. It was all the Cajuns wanted.

Nearly a century after the first refugees from Nova Scotia settled in southwest Louisiana, an influx of German farmers brought the accordion. The accordion was a German invention and was the rage in European countries about the time the farmers migrated to Louisiana in the 1800s. The Cajuns were quick to adopt the primitive accordion as their own.

Savoy says that for many years following, Cajuns musicians, who knew nothing about musical theory, were unable to tune the accordion to the fiddle. As a result, the accordion was rarely played with the fiddle until after 1900.

Once the Cajuns learned how to match the accordion with the fiddle, however, the Cajun dance band contained both instruments. Savoy says that several merchants in the New Orleans area made a great deal of money importing the accordion from Germany for the Cajuns.

“We not only absorbed the German farmers into the Cajun culture, we absorbed their musical instrument as well,” Savoy notes.

Little is known about when the triangle came into use in the Cajun band or where it came from. It served as a percussion instrument and kept time for both the fiddle and the accordion. Today, the simple triangle continues to be an important part of the Cajun band.

In the 1920s, when the phonograph began making an impact on all folk cultures, the Cajuns learned about the guitar. And, with the guitar came country and western music, which was to have a definite impact on the music. The guitar was as portable as the accordion and fiddle. It provided the bass sound lacking in both Cajun instruments. The Cajuns were quick to adopt it.

With the native Louisiana Cajun music came Louisiana Cajun lyrics to fit the native mood. Mrs. Holmes notes that Cajun music seems to have grown “from spontaneous outbursts and varies with them. Even the same song might be quite different before and after a dance.”

Like folk songs everywhere, Mrs. Holmes points out, Cajun songs echo the incidents of life:

“These songs portray the young man as primarily interested in the girl loved, la belle. He loves her, he tells her good-bye when she marries someone else, he wants to know what he has done to make her treat him so mean, he blames her because he is poor, he thinks of suicide when she does not love him; he flatters her; he dreams of her; he regrets her when she sends him away; he reproaches and threatens her for leaving him; he begs her to make her little package and go to his house with him; or promises to feed her upon pain perdu (French toast), pain de mais (cornbread) or caille (clabber); he asks her mother for her, which shows the persistent French tradition of marriage contracts; he advertises that he wants to marry and states impediments to marriage; he weeps with a broken heart when she dies before he does; and if he dies before she does, he begs to be buried in the corner of her father’s yard so that he may look upon her dear little eyes throughout eternity.”

“Probably the ardent wooer is attentive after marriage. Only once he is accused of leaving his wife and sick baby on Sunday night to go to a gambling joint. Then the wife complains that days which were rosy for her before marriage have become as green as cabbages.”

“If the Cajun is no longer in good favor of his belle, or if he thinks of far-away lands, the main place he sings of is Texas. This is attributed to the fact that during the early days of Louisiana, Texas represented the far-off country of the unknown, the country of great adventure. Consequently, when a young maiden gave a ‘coat’ to her lover, signifying in the Cajun that he was to leave her house never to return, he went to Texas to face his destiny and forget his belle.”

Other Cajun songs are little more than whimsical statements about people, places and things. One of these, entitled “The Girls of Mamou,” translates roughly as follows:

The girls of Mamou never drink, it is said,

They drink like men and they get drunk as robins.

Let’s go to Mamou to have a good time,

Let’s go to Mamou to have a good time.

The idiomatic expression “as drunk as robins” refers to the habit the birds have in Louisiana of eating the fruits of the chinaberry tree and becoming too inebriated to fly.

Although Cajuns have been the brunt of hundreds of ethnic jokes, some of their folk songs are, themselves, ethnic slurs, particularly against blacks and Italian immigrants.

Few, if any, traditional Cajun songs deal with religious topics. Mrs. Holmes notes that no Cajun songs show “shouts of joy at getting religion nor the low, moaning, minor note, both so characteristic of the English Negro spirituals.”

Cajuns are nearly 100 per cent Catholic. There are several theories as to why Cajuns don’t sing their religious feelings. Perhaps, some say, Cajuns throw the responsibility of salvation on the church. It has been said that perhaps Cajuns are too frivolous to be concerned with matters of another life.

Missing, too, are songs that deal with the miseries of “le grand derangement,” when the Acadians were cast out of Nova Scotia and forced to re-settle in Louisiana. During that time, whole families were separated, disease and servitude plagued the hapless Acadians and all the elements for sad folk songs were present. Yet, the Cajuns of today don’t sing of that era.

The most popular Cajun songs being played today in the clubs and bars in the Cajun parishes are the waltzes and “two-steps.” The latter contain a heavy two-four beat and are played fast to allow dancers to display their skills at the “two-step” dance. The two-step is a free form dance, which contains elements, one writer said recently, of “an Apache war dance.” In fact, a Cajun well into his 70s recently performed what he called “un danse antique” (an old dance) at a bar in Mamou and it resembled an Indian dance even more closely than the modern Cajun two-step. The old man claimed that the dance was brought to Louisiana from Canada, but one cannot help but wonder whether some of the steps may have been learned from the Indians of the region who were present in large numbers when the Acadians arrived.

The dance performed to the waltz time is quite similar to waltzes everywhere. Older musicians say that in the early days of the 20th Century, when women wore long dresses, the men would exaggerate the waltz step to make sure the “women’s dress tails would pop as they were swung around the dance floor.”

Today, it seems, the most graceful dancers are the older Cajuns who were reared dancing the waltz. At many of the dance halls, there are as many, or more, dancers over 60 as there are under 60. The older Cajuns like to dance as much as the younger ones. In fact, some dance halls scattered throughout the region cater exclusively to oldsters, discouraging youngsters from attending by playing more traditional forms of Cajun music.

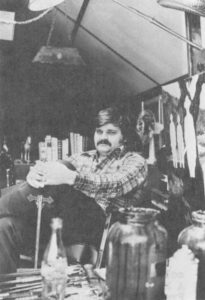

George Fontenot of Mamou is a fiddler who has spent nearly 50 years playing Cajun music for weekend dances. A barber by trade, he says he has found plenty of time to play his fiddle. Although he is now retired from barbering, he continues to play his fiddle daily. He has built 13 fiddles and is now working on another one.

“I’ve played for house parties that were so big, the group had to be divided into four or five groups,” Fontenot said. “Each group was given a different colored ticket. After the ones holding the red tickets danced awhile, they were asked to leave the floor so the people with green tickets could dance. The people who were giving the party sometimes hired deputy sheriffs to oversee the dance couples. Outside the home, there was always a fight or two during the evening.”

Fontenot says one of the most popular dances in bygone days was the “reel,” which is more closely associated with folk cultures that descended from Scotch-Irish and English ancestors. Savoy believes the Cajuns may have learned the reel from friends and neighbors in Canada before being expelled.

Another popular dance of days gone by was the “country dances” or “quatre danse,” as some French-speakers call it. While it looks a great deal like the square dance, which originated with those of Scotch-Irish heritage, it has considerably different characteristics. Paul Tate, a Mamou attorney and expert on Cajun music and dances, says the differences are deliberate since, he believes, the traditional Scotch-Irish square dance was too reminiscent of the English culture that produced cruelty to Acadians in Canada.

Fontenot is a perfect example of how devoted Cajun musicians are to their music. The fiddler has a heart condition. His heart is assisted by a pacemaker. Recently, while fiddling, Fontenot overdid it a bit and pulled a wire loose from his heart. He was rushed to New Orleans where the wire was re-inserted. According to a friend, Fontenot was back playing the fiddle the day after he left the hospital.

In his later years, Fontenot has become quite interested in the folk songs sung in Louisiana during the early 1800s. He is seeking his heritage through a study of folk songs. He says it is a most satisfying pursuit.

Compared to the number of accordion players, there are only a handful of Cajun fiddle players left. Cajun music followers say there are two reasons for the lack of interest in fiddle players. First and foremost is the fact that, in recent times, the fiddle has taken the back seat to the accordion in the Cajun band. The accordion has become the lead instrument. Secondly, it appears the fiddle is more difficult to learn to play.

The Cajun accordion is a copy of those first accordions that made their way to Louisiana in the late 1800s. The Hohner Co. of Germany continues to make the basic accordion used by the Cajuns.

Unlike the elaborate “piano accordion” played by Lawrence Welk, the Cajun accordion has buttons instead of piano-type keys. On the “bass side” of the accordion, there are only two bass chords, which explains why many Cajun songs contain only two chords–those found in the bass reeds of the accordion.

The accordion comes from Hohner with what the Cajuns call a “wet” sound. This comes from the careful tuning of the reeds to produce a tremolo desirable in most music. Cajuns apparently do not like this sound because Cajun musicians retune the reeds by filing them to produce a flat or “dry” sound.

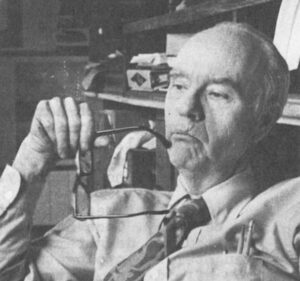

No one can explain why Cajuns alter the factory tuning of the accordions. But, Mark Savoy, who builds accordions to sell, builds “dry tuned” accordions for sale in Louisiana.

The same basic accordion is used among the French-Canadians in Quebec Province. Savoy, whose accordion shop is located in Eunice, makes accordions for French-Canadians as well as Cajuns. He says that about half of his accordions are sold to French-Canadian musicians.

“I build my accordions to last,” Savoy says. “The German imports can’t withstand the hard-driving French-Canadian and Cajun songs.”

The accordion-making business is good, Savoy says, despite the fact that one of his instruments sells for $650 (compared to less than $150 for a German-made model). At last count, Savoy had orders for nearly 30 accordions. Most of those orders are from Quebec.

Savoy says there are about a half dozen accordion-makers in Louisiana and most have their hands full just filling orders for the instruments.

“As Cajun music becomes more popular, this type of accordion becomes more popular. And, since people want accordions that will last, they prefer to buy handmade instruments,” Savoy says.

The 35-year-old Cajun is intensely concerned about the culture that produced him. “I think people my age are probably the last true Cajuns,” Savoy says. “Not many people younger than me know how to speak French. And, while Cajun music is still popular, so many of the younger musicians in this area have given up the music of their people for country and western and rock n’ roll. They learn their music from records instead of from their fathers and grandfathers. They want to learn to play music that’s “in” in the rest of America while their own native music is all around them.

That isn’t to say that Cajun music isn’t recorded, however. Two record companies do a thriving business in Cajun music. La Louisianne Record Co. of Lafayette and Swallow Records of Ville Platte both specialize in turning out Cajun music for Cajuns.

Floyd Soileau (pronounced Swallow) is producer of Swallow Records. His records are distributed throughout southern Louisiana and by folk music distributors in the big cities of America. Soileau says the Cajun record business is booming and he expects the boom to continue.

“Every day, it seems, we get more and more mail orders from people all over the United States who’ve heard some Cajun music and want to hear more,” Soileau says.

Although interest in Cajun music has remained constant, the interest seemed to intensify after World War II veterans returned home, according to Revon Reed of Mamou, a Cajun music enthusiast and high school teacher.

“Many of the Cajuns gained new pride in the culture during the war,” he says. “Some of them were translators and many others found themselves in great need in French-speaking countries. When they returned, they were prouder of who they were and the French language skills they had.”

The music and the language are inseparable, with one supporting the other. But, while the language cannot be exported to mainstream America, it seems the simple homemade music of the Cajuns holds a special attraction for those in the mainstream culture.

But, what effect will the widespread interest in Cajun music have on the folk culture? Will the culture be mutated? Will it become commercialized? Will thousands of tourists come to Cajun Country, cradle of Cajun music?

“I think about that sometimes,” says Soileau. “Of course, we like to have tourists visit here in southern Louisiana. But, I sometimes wonder what will happen to our culture if we’re inundated by outsiders.”

Some Cajuns point to New Orleans, once the capital of French-speaking peoples of Louisiana. Today, with the thousands of tourists and English-speaking residents, New Orleans is little more than a slick commercial memory of past French glories, a place where even the natives have trouble finding good jazz, the music that made the Crescent City famous.

“I’d hate for that to happen to us,” says a Mamou businessman. “Of course, I guess we’d all be rich, but we’d be without our roots.”

Received in New York on February 9, 1976.

©1976 Dave Peyton

Dave Peyton is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Huntington Advertiser (West Virginia). This article may be published with credit to Mr. Peyton, The Huntington Advertiser, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.