“Mountain music will set you free” is a popular message on tee shirts this summer in Appalachia.

The slogan expresses the opinion of a rapidly growing cult of mountain culture enthusiasts who gather in scores of places throughout the summer to celebrate the simple joys of Appalachia.

But, as the crowds grow, those who seek to preserve mountain heritage say they’re ready to wear tee shirts with the message “Mountain music is getting out of hand.” Some say they’re ready to carry banners proclaiming, “Appalachian culture is its own worst enemy.”

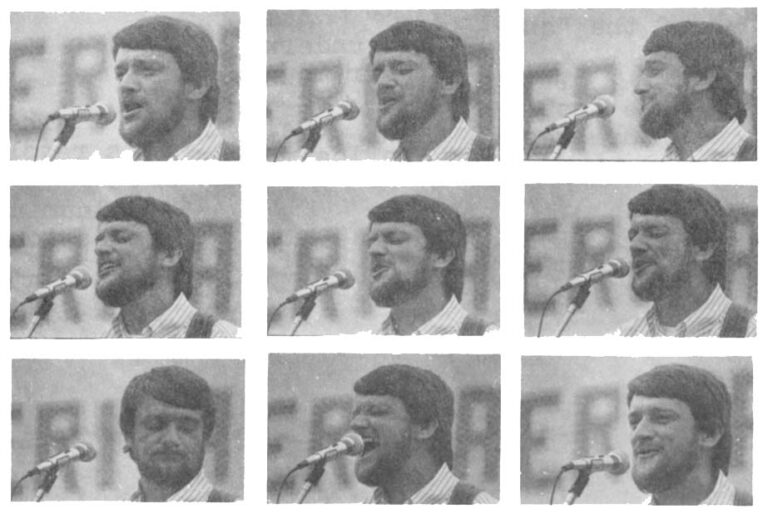

Mountain festivals are as common to Southern Appalachia as family gatherings were long ago. But, unlike family reunions, which attracted no more than a handful of clan members, today hundreds or thousands congregate at campsites among rolling hills on private farms and in small mountain towns for weekends of music, crafts and mountain heritage.

The popularity of the simple, joyous mountain culture celebration has affected the whole United States. The festivals bring people (particularly the young) into the mountains from all parts of the country.

The resulting mob scenes have been more than unpleasant. Drunkenness is not uncommon. Drug arrests are on the increase. Acid rock music, screaming from loudspeakers mounted atop gaudy vans, often drowns out the more serene sounds of unamplified mountain instruments.

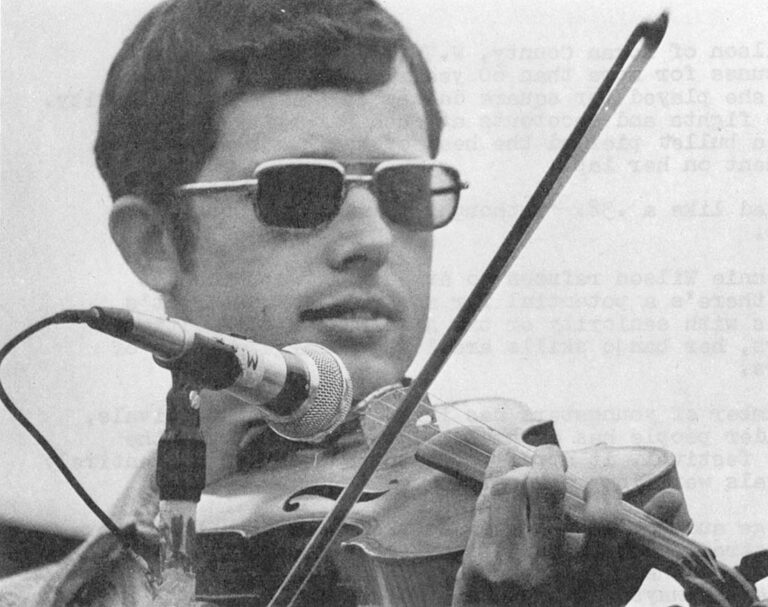

Mountain fiddle and banjo contests, once the exclusive domain of the old mountain musicians, now are being won by those under 30. Many of the “youngsters” have had classical music training. Instead of learning the music from their fathers or grandfathers, many of the young have learned from recordings of native mountain musicians.

And, for a few dollars, any serious violin student can purchase books, which give specific instructions for playing the mountain tunes. Most of the tunes never were written in sheet music form until recently.

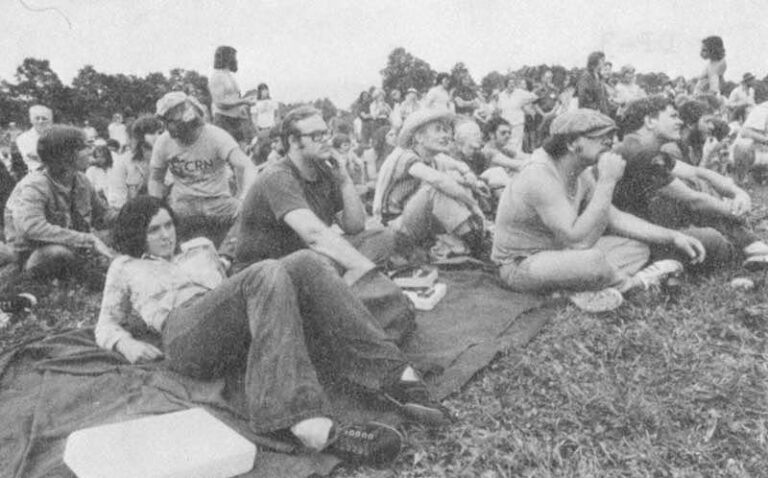

A rowdy crowd of between 5 and 6,000 at the Mountain Heritage Folk Festival in June near Grayson, Ky., prompted some organizers to consider drastic changes for future festivals.

One mountain ballad singer was hooted off the stage simply because her soft, sweet style didn’t impress those with ears attuned to loud, fast music. And, when fast mountain tunes were featured on the stage, members of the audience danced among those seated on the ground, making the very act of listening a dangerous experience.

Some members of the Mountain Heritage committee have proposed a festival by invitation only for 1976. Even those committee members who think that remedy too harsh admit that the festival has decayed into a bad imitation of the now-famous Woodstock festival. That sort of atmosphere is alien to Appalachia, they say.

The administration of Alice Lloyd College at Pippa Passes, Ky., solved the problem of unwanted festival crowds long ago. The college sponsors an annual event that can only be described as a “semi-private” festival.

A staff member says the festival dates are changed each year. “Sometimes we hold it in June, sometimes in August,” he says. “We never advertise beyond the immediate four-county area. The only public notices appear in a few weekly newspapers. We simply try to discourage outsiders from attending.”

Don West, the venerable mountain activist and steward of the Appalachian South Folklife Center at Pipestem, W.Va., sponsors an annual festival at his center. Mountain residents are admitted free. All others pay $10 for the weekend.

The West Virginia State Folk Festival at Glenville may have grown too large for the small college town in the heart of the Mountain State, according to Mack K. Samples, a native West Virginian and Glenville State College registrar who began attending the festival in 1961.

“Back then,” he says, “they had trouble finding enough musicians to put on a decent show in the college auditorium.”

This year there were enough musicians for three four-hour shows. And all the musicians in town didn’t play on the stage.

“The festival is getting too big for Glenville,” says Samples, one of the festival organizers. “I don’t know what’s going to happen in the years to come.”

This year’s fiddle contest at Glenville was won by John Morris, a young Clay County, W. Va. native who is a semi-professional musician. Morris was schooled in the mountain fiddle traditions by Lee Triplett, Ira Mullins and others. These men are reverently referred to by old-time music fans as “the Clay County fiddlers.”

This year, Morris won out over those much older than he, and, sooner or later, the traditionalists say, the day will come when a young fiddler from New Jersey, who learned from “Twelve Easy Steps to Old Time Fiddling,” will take the coveted Glenville prize.

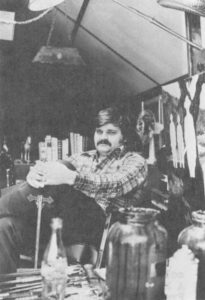

Each festival features its own contingent of craftsmen. While most of the crafted items are high quality and are in line with mountain traditions, each festival has its share of poor quality, mass-produced items sold as handcrafts. It’s not unusual to see fake Indian jewelry being sold at Appalachian festivals. Elaborate carved and cast candles also are popular, although not traditionally Appalachian.

Nearly every festival features a cadre of dulcimer makers. Dulcimers are native Appalachian instruments. They are relatively simple to make but those of high quality are scarce. Since few buyers know what a dulcimer should sound like, many purchase instruments of poor quality for high prices.

In all, the visitor to an Appalachian festival who is not a student of traditional Appalachian culture can easily walk away with a distorted view of the Appalachian heritage. Like the blind man and the elephant, the festival sees a small portion of the real Appalachia, if he sees any of it.

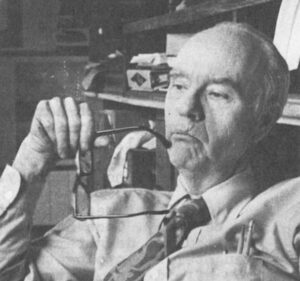

Dr. Norman O. Simpkins, an expert on Appalachian culture from Marshall University, Huntington, W. Va., says the modern mountain festival has become the epitome of the romanticization of southern mountain culture — a sure sign that the real culture is about to fade away.

Why did such festivals begin? Dr. Simpkins says the potential for such gatherings has always been in the culture. In his “Informal, Incomplete Introduction to Appalachian Culture,” he notes that the Celts, from whom much of the Appalachian culture is derived, “loved music and many forms of oral literary competition.”

Gathering for the purpose of singing the old songs and telling the old stories and legends is not something new in Appalachia, but inviting “outsiders” is.

For nearly two centuries, the culture was passed from one generation to another through family gatherings, community barn raisings, dances and church and school socials.

But these were clannish gatherings. One had to be a member of a family, church or community before being invited to attend. Community pressure dictated a standard of behavior.

The elders of the community spoke, performed and led. The younger members listened and absorbed, preparing themselves for the time they would lead.

To be sure there was drunkenness and rowdiness, but those who were disruptive were spirited away in disgrace.

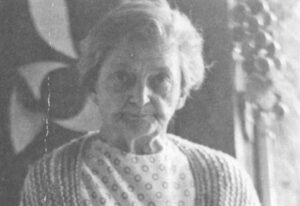

Jennie Wilson of Logan County, W. Va., has been playing mountain banjo tunes for more than 60 years. She tells of the early days when she played for square dances in her native community. Stories of knife fights and shootouts at such gatherings abound. Once, she says, a bullet pierced the head of her banjo while she held the instrument on her lap.

“It cracked like a .38. I thought to myself, ‘God, I’m shot,’” she says.

Today, Jennie Wilson refuses to attend many Appalachian festivals where there’s a potential for mob rule. Whether it’s wisdom that comes with seniority or the Appalachian’s traditional fear of outsiders, her banjo skills are lost to large numbers of festival visitors.

As the number of youngsters has increased at the festivals, the number of older people has dropped proportionately. At the recent Glenville festival, it appeared that two separate and entirely different festivals were in progress.

The college auditorium, located at the crest of a hill above the town’s main street, drew the older citizens from surrounding counties — those who perhaps remember when only the old were interested in the old ways.

Few of the elders ventured into the main street area where the young played their instruments under the stars until daybreak for three days. Occasionally a group from the main street would climb the hill to play in the auditorium, but for the most part there was an unspoken law that those who “played on the hill” didn’t play in the streets, and vice versa.

The fear of “young hippies” seems to be more prevalent in Appalachia than in the rest of the nation. In the deeper parts of Appalachia, it’s not uncommon to see young men and women, their faces scrubbed, their hair groomed, looking for all the world like pre-1960 all-American teen-agers.

Thus, when large numbers of young “free spirits” congregate on the streets of small towns, the uneasiness of the elders is apparent.

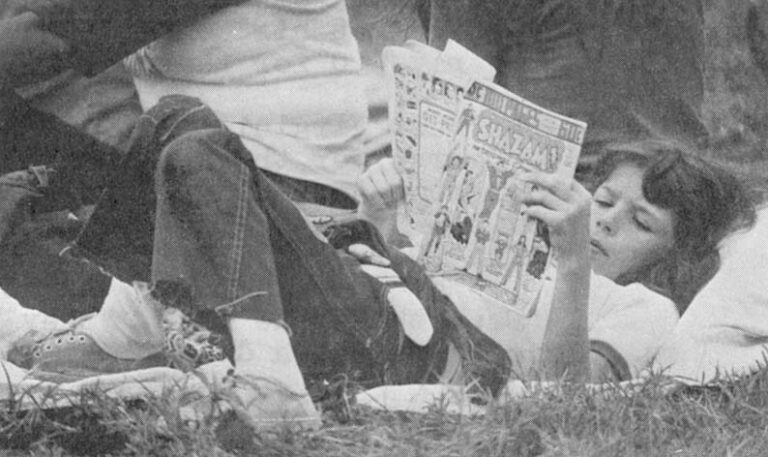

But, in the young generation there seems to be two sects — the disruptors and those who are the most devoted followers of the Appalachian cult.

The latter group reveres the old traditions. Many are involved in a back-to-the-land movement in Appalachia, which stresses the old mountain values of self-reliance and pride. They seem to have been swallowed up by what Dr. Simpkins calls the romantic aspects of the culture.

These “new pioneers” see only those qualities, which to them are admirable. They base their alternative lifestyles on the rugged independence of the ancient mountain man. Often they choose to ignore the negative — isolation of the mountains, lack of proper medical facilities and educational opportunities, poor roads, pockets of profound poverty and ignorance that continue to haunt some deep mountain hollows.

Life to the young devotees is one long fiddle tune or lilting mountain ballad. The rising number of homesteads and farms is evidence of the romantic lure of Appalachia. But, many of the homesteads are abandoned by young starry-eyed couples who found life on a mountain farm more difficult than they had imagined. The hard realities of life in the mountains defeats them.

The mountain festivals, which draw the young outsiders, are, for the most part, heavily subsidized by a unit of government or private group. Some charge no admission while others charge spectators nominal fees.

The best known of the “cultural explosions” in West Virginia is the Mountain State Arts and Crafts Fair at Ripley, which annually draws nearly 50,000 spectators to the five-day event.

The fair, which emphasizes mountain crafts, is sponsored by several branches of state government. The fair’s governing board, fearing the highly successful event will decay like some others, this year sent exhibitors a detailed two-page list of rules. Among the rules is a stipulation that music not be played except in designated areas.”

Camping on the fairgrounds is prohibited. The closest campground is several miles away. Admission for one day costs $2. State police and sheriffs patrol the grounds constantly. Alcoholic beverages are not permitted. Several young craftsmen complain that the fair committee passes them by in favor of older exhibitors.

Whether or not the Arts and Crafts Fair is on a sound cultural basis, it means a lot of money for the serious state craftsmen. To transform the Ripley fair into another Woodstock would be disastrous for some, one craftsman said.

“Too many youngsters drive away the older, more affluent people — the people who buy rather than browse. I make half my annual income from sales at Ripley. If the kids take it over, the buying public will stop coming. If that happens, I’d be sunk for sure.”

What’s it all coming to? Will the time arrive when it will no longer be possible to hold festivals, which propagate Appalachian heritage?

But, even with today’s festivals, are spectators getting the true picture of Appalachian culture? Sociologists and those concerned with preserving the culture are asking themselves if ignorance of a culture might not be better than a distorted view.

And, what about those who have made the culture their hobby? Are they changing the culture by being “part-time mountain people?” What effect does a New Yorker have on the region when he spends weekend after weekend in small mountain communities, soaking up mountain culture? Does a bit of New York “rub off” on Appalachia each time he visits?

Dr. Simpkins says he sees noticeable changes in those people who once were called “original Appalachians” but who have gone through transformations because of their associations with mainstream Americans at mountain festivals. The process of change is too rapid to be called evolution. It’s revolution, pure and simple, some say.

And, the worst may be to come. As 1976 approaches, plans are underway for scores of communities in Appalachia to flaunt their mountain heritage at Bicentennial tourists.

Demand for mountain festivals increases as mainstream America moves farther from the old value systems and is smothered in plastic wrap and aluminum beer cans. Tourists want to partake of the “quaint.”

But, in the rush to provide tourists with the quaint, some festival organizers forget about regulations for themselves and those who will be attending.

The time may soon arrive when the sole distributor (the Appalachian region) will be able to offer only slick, professional replicas of the “real thing.”

Received in New York on July 10, 1975.

©1975 Dave Peyton

Dave Peyton is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Huntington Advertiser (West Virginia). This article may be published with credit to Mr. Peyton, The Huntington Advertiser, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.