From inside an automobile circling the first nearly completed section of Le Mirail on the project’s system of ring roads, little appears to be very different about this large new quarter of the old city of Toulouse in southwestern France. The familiar perimeter of apartment buildings, some boxy four-story walkups and many more long, lean elevator buildings of ten to fourteen stories each, circumscribes an unseen core where one expects to find an open parking lot and/or unused swatch of newly laid sod dotted with little stake-supported saplings. It is the exterior face of countless mass housing developments and “new town” projects throughout Europe.

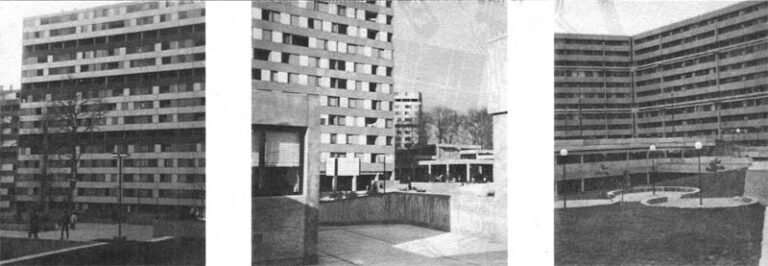

But when the automobile is left in the two-level parking garage found at one end of this section, called Bellefontaine, and one climbs the stairs to the concrete mall covering the garage, the familiar gives way to a different and unexpected place. This is the infamous pedestrian dalle of Le Mirail: a huge raised concrete slab, two stories above street level in some places, that has been variously castigated by French planners and journalists as “ghastly,” “gray,” “barren” and “inhuman.”

The dalle begins at the edge of an inviting group of shops and school rooms directly above the entrance to the parking garage, sweeps across a football field or more of space bordered by imposing apartment buildings, squeezes through a truck-size opening in one building and opens up again into another vast expanse delimited by gray, white and beige-banded walls of more stacks of apartments. This “ocean of concrete” proved such a shock for one French writer, Mylene Remy, that he first described it as a “heartless Kafkesque universe” in a long article on Le Mirail in a leading French review of politics and government. “Am I in Pompeii after the catastrophe?” he asked.

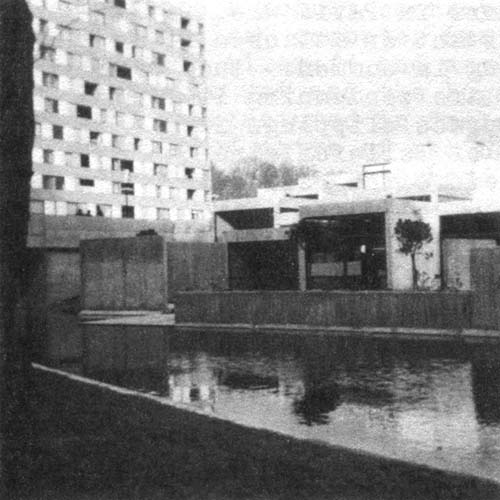

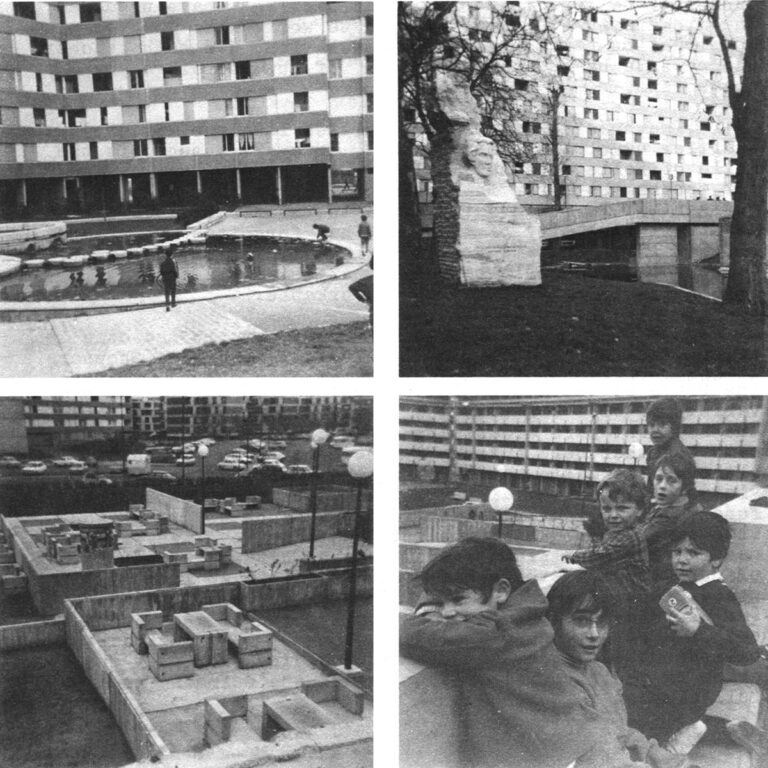

As he began to walk around the dalle, however, Remy discovered the intricacies of its various different levels, each connected by steps and ramps that also lead to the parking areas hidden below. He found numerous large and small play areas with both grass and concrete surfaces, several secluded, tree-shaded pools of water with fountains and statuary, small planted areas and picnic spots, and surprisingly large parks filled with majestic old trees. There are even little brick garden buildings preserved from the spacious grounds of several old chateaux that had previously occupied the site on the west bank of the winding Garonne River, across from the older built-up areas of Toulouse.

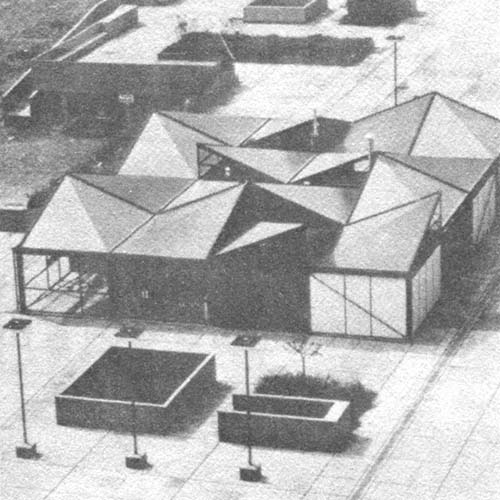

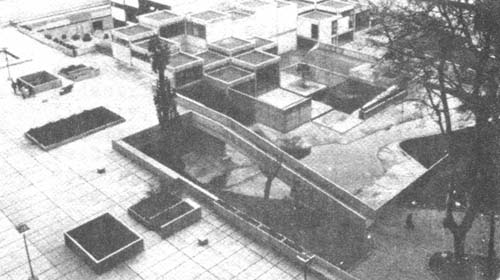

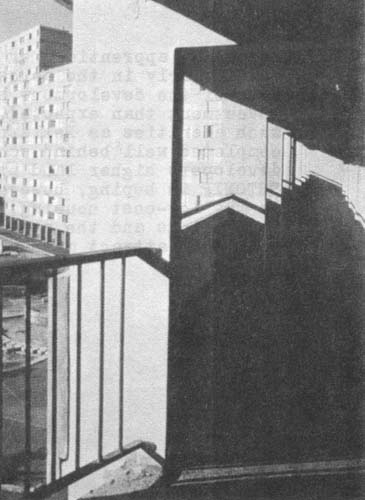

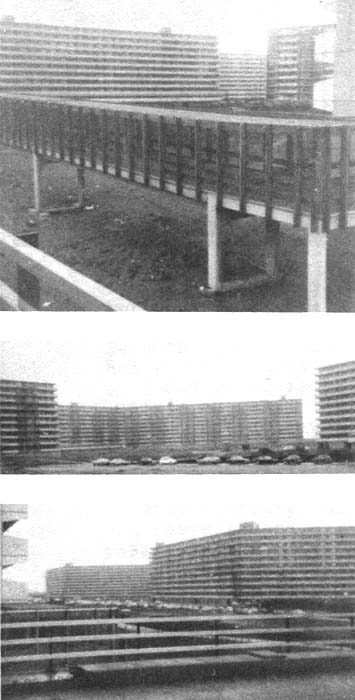

first section seen from stores (note small passage under building to second section)…and second section, with social center in middle and parking ander dalle.

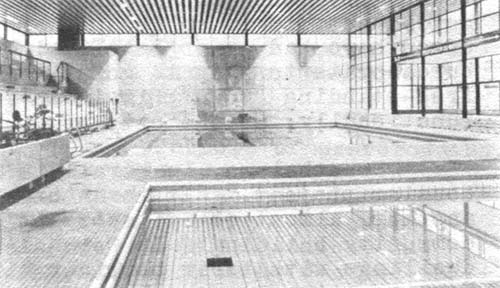

Rising up from ground level through the center of the first broad section of the dalle are a gymnasium and two-pool natatorium. Each is walled with glass so that passers-by on the mall can peer in one side, while those playing inside can look out onto an idyllic garden and pond on the other side of the building. Since Remy’s visit 18 months ago, more of this multi-level “Maison du Quartier” has been completed, providing a library, youth center, craft rooms and meeting halls for Bellefontaine residents, as well as a physically appealing focal point on the dalle. A short distance away, in the middle of the second large expanse of concrete, are interconnected bright colored cubicles that form a social center for welfare and health services.

Closer inspection of what presently exists at Le Mirail reveals still more. The dalle of Bellefontaine is actually only a small part of an extensive pedestrian circulation system that eventually will enable residents to walk as far as five kilometers from their homes – to every school, store, recreation and social facility, and to most places of employment in Le Mirail – without ever crossing the path of a car. Automobiles will be able to circulate efficiently on an equally extensive system of roads circling around and under the pedestrian areas, with plenty of parking spaces, many of them covered and out of sight beneath buildings and malls.

Behind the bland, chalky facades of the apartment buildings are other surprises. Most apartments extend to both sides of the slim elevator buildings, with loggias on each end, one looking out onto the urbanized concrete dalle and the other onto a quiet, green wooded park. Sliding panels enable residents to change the loggias from outdoor balconies to indoor rooms, changing the face of the building in the process. In some apartments, these movable panels also permit redesigning of the room layout. Apartments on the sixth, ninth and twelfth stories of the taller buildings open onto outdoor corridors intended to be above-ground pedestrian “streets,” where upper story residents can meet each other and their children can play safely near their front doors.

Still other innovations at Le Mirail are more difficult for the visitor to discern. Inside the bulky, rather unattractive heating plant is machinery that can incinerate all the garbage of Toulouse, including Le Mirail, and use the energy produced to provide heat and hot water for every home and office of Le Mirail. The heat and hot water pipes, along with all other utility lines for Le Mirail, have already been put underground in accessible, lighted tunnels large enough for maintenance workers to walk or ride through. The elementary schools are low, handsome clusters, each built around an atrium. Each classroom has a glass wall facing the outside that can be rolled aside in good weather for al fresco learning.

Top: Looking from park toward library and meeting rooms

Bottom: and natatorium (right).

These experiments and the development of Le Mirail itself are being carried out by private builders and a regional public corporation jointly backed by banks, local municipalities, public utility districts and the French equivalents (though much less autonomous) of U.S. counties and states, representing a large region (by French standards) nearly 200 miles square around Toulouse.

This kind of regional and public-private cooperation, as well as the wealth of experimentation with new urban concepts in Le Mirail, is exactly what has long been urged for the concerted development of new towns in the United States. But in France, and particularly in Paris, there is little liking for, or even interest in, Le Mirail.

“Le Mirail? The French do not even consider it to be a new town,” scoffed one housing official in Paris. “From what I hear, Le Mirail is just another housing project.”

This community planner and many others in Paris who, in interviews, dismissed Le Mirail as unimportant or attacked it as grotesque and unworkable all have one thing in common: they have never visited Le Mirail themselves. They are condemning it largely on the basis of some unfavorable press clippings from the time when the newly constructed dalle of Bellefontaine supported little life. (Like “Brasilia before the residents moved in,” Remy wrote.)

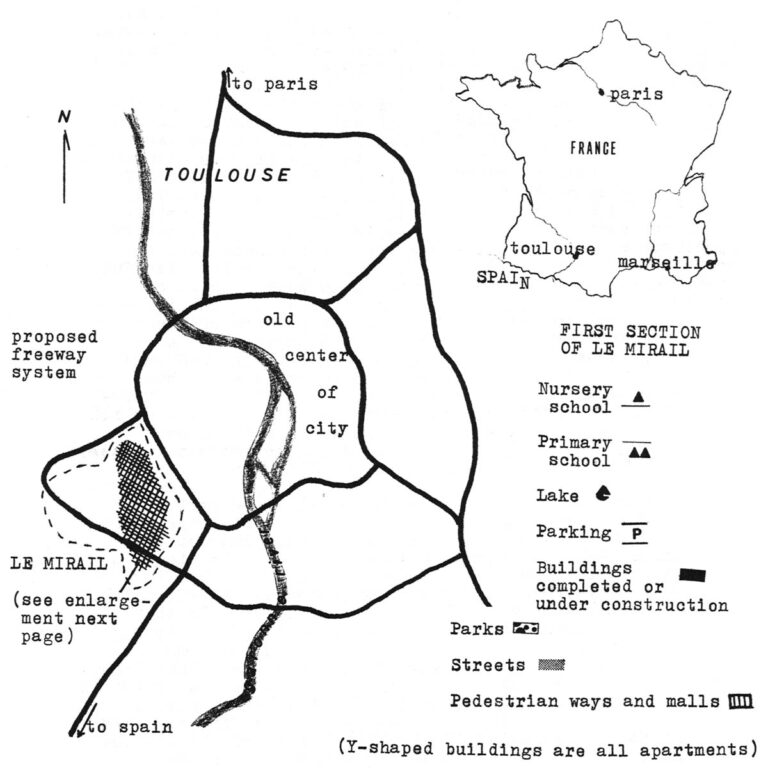

It is also clear that, for many Parisian officials, anything happening in a “provincial” place like Toulouse is almost automatically considered inconsequential. Toulouse – “la ville rose” – is known chiefly for its brick buildings with rose colored roofs, a huge Romanesque cathedral, the proximity of increasingly numerous ski resorts in the nearby Pyrenees and little else. Located just sixty miles from the Spanish border, Toulouse is almost as far from Paris as it is from Madrid. It is not even on the major train or auto routes between the two capitals, or between Paris and Marseille, the “second city” of France.

Le Mirail is not one of the nine officially designated new towns (five of which are in the Paris area) sponsored by the French government; it is an independent project of local officials who often have had to do battle with antagonistic national government bureaucrats to keep it going. And Le Mirail obviously is not a free-standing “town”; it is an integral part, geographically and functionally, of the city of Toulouse.

Nonetheless, Le Mirail is much more than “just another housing project.” It is an experiment testing, in one way or another, almost every important contemporary idea about new community building: Le Corbusier’s giant “habitational unit” dwellings with their corridor “streets”; Jane Jacob’s belief that housing, stores, schools and other functions must be kept close together in highly urbanized neighborhoods (although Le Mirail is not the revitalized old neighborhood that is her most frequently cited model; Lewis Mumford’s concept of regional planning and development of experimental communities unfettered by traditional notions or development pressures; the “linear center” multi-function pedestrian boulevard pioneered by Israeli new town builders, and, finally, the idea, now gathering impetus in both Europe and the U.S., of harnessing the inevitable growth of medium-sized cities and towns rather than concentrating only on the building of satellite new towns. The project’s designers and developers also are attacking urban environmental problems: waste disposal, generation of energy, air and water pollution, tree and water conservation, pedestrian freedom and control of the dangers and nuisances of automobiles.

This decidedly unconventional project sprang from the necessity of solving a common urban problem: how to deal with the runaway growth of Toulouse. In 1954, the city’s population was 267,000; by 1970, it was 400,000 and rising rapidly because of Toulouse’s robust economy. Toulouse has large concentrations of electronics, computer and chemical firms and is the center of France’s aircraft and aerospace industries. The workhorse Caravelle passenger jet and the huge supersonic French-British Concorde are both manufactured in Toulouse. (Our visit to Le Mirail included the unexpected extra of seeing and hearing the gangly, hawk-nosed Concorde roar by overhead on a test flight.)

One reason for the attraction of Toulouse for these industries is the excellence of its technical universities and trade schools. Toulouse is second only to Paris in the number of students (40,000) attending universities there, and the majority of these students are studying engineering and various applied sciences. Built around the various highly specialized schools, such as those for aerospace sciences and engineering, are the research and development complexes of private industry. Although it is located deep in the otherwise impoverished mid-south of France, Toulouse has become a prosperous city.

In addition to the fruits of its own efforts, Toulouse reaps benefits from a national government aid program, begun in 1963, for the decentralization of the nation’s economy. Businesses that move out of Paris and its environs to the eight provincial regions of the country, including the southwest Midi-Pyrenees region in which Toulouse is located, are rewarded with tax cuts, better government loan rates and expanded patent rights.

Predictably, as Toulouse grew, so did problems of overcrowding. Its downtown maze of charming medieval streets became choked with traffic, its old brick buildings were filled to the bursting, and disorganized clumps of unappealing high-rise housing cropped up on its outskirts. Toulouse’s remarkable mayor, Louis Bazerque, saw a disturbing pattern forming as early as 1960, when he decided to channel as much of the city’s new growth as possible into a carefully planned new quarter to be built just across the Garonne, within the city limits, on 2,000 acres of unused chateau lands not far from several of the large new industrial and educational complexes. An outer freeway system to be developed along with the new quarter would carry through traffic around the old city center and to and from the new quarter and industrial areas.

Bazerque envisioned a highly urbanized “new town” with a certain autonomy, personality and sufficiency of its own that would nevertheless be “integrated with the traditional city of Toulouse,” creating a new center of population, commerce and industry to balance the old one across the Garonne. However, this was not a popular notion in France at the time, particularly inside the powerful national government bureaucracy. DeGaulle’s housing minister, Jacques Maziol, was frankly opposed to such large-scale projects and especially one with so high a density as was planned for Le Mirail. Instead, Maziol favored renovation of older inner city housing and the construction of American-style single-family homes in the suburbs. This, he thought, was France’s housing market of the future.

Events have proved Maziol’s judgment wrong. Although a portion of upper middle class families have eagerly moved to new suburban single-family homes (enriching American developers like Levitt and Kaufman-Broad, who are building in France), a majority of French homebuyers still prefer the lower cost and lighter responsibility of owning or renting an apartment. Meanwhile, the increasing chaos of uncontrolled suburban growth around the larger French cities has forced the Pompidou government and Maziol’s successor as housing minister, Albin Chalandon, to begin a belated new town development program, with the national government providing low-interest financing and priority for schools, roads, mass transportation, recreation and other needs for the nine officially sanctioned new town projects.

But when Mayor Bazerque of Toulouse decided to launch Le Mirail, all this was still years in the future. And, today, the characteristic inflexibility of the French bureaucracy and Bazerque’s non-Gaullist independence of the national government have kept Le Mirail frozen out of the official French new town program. Bazerque has thus been forced to work with what has been available to him: the incentives for businesses relocating in the provinces, and a variety of existing government subsidies for the construction of housing for low and middle income families.

Toulouse had already formed, in 1956, a local public-private development corporation supported by the local Chamber of Commerce, the governments of Toulouse and its department (county), Haute-Garonne, the local offices of the national government’s low-cost housing programs, and the local branch of the government savings bank. In time, it was joined by the government of six surrounding departments to form the Societe d’Equipment de Toulouse Midi-Pyrenees (SETOMIP). In addition to building the region’s low-cost government housing, it has developed several industrial parks (adding further to its capital with the profit of buying and selling or leasing this land), renovated a 15-acre neighborhood of old buildings inside central Toulouse, developed regional recreational communities and hotels, and built new sewage treatment and garbage disposal plants. Its biggest project by far, though, is Le Mirail.

SETOMIP buys, sells, leases and develops land in Le Mirail. It builds the roads and develops all public areas. It provides all the utilities (which are administered by the appropriate government body), and thus has been free to design innovations into this equipment. Only a small portion of the housing, along with the stores and businesses, are being developed by private interests who secure the land from SETOMIP.

SETOMIP put the overall design of the project into private hands, those of a visionary Greek architect and planner, George Candilis. An ardent student of the Le Corbusier and Mediterranean schools of design, Candilis had set out to fulfill four specific objectives at Le Mirail: to bring all activities of urban life back within pedestrian access of every home; to keep cars and pedestrians on two completely separate circulation systems; to preserve the site’s beautiful green spaces; and to minimize, if not eliminate, the harmful effects on the environment usually produced by moving 100,000 people onto land where only a handful had lived before. Philosophically, Candilis wanted to go still further and use the very latest advances in planning and technology to recreate the medieval city – a place where one could walk to get whatever one needed, where inhabitants would be brought into frequent outdoor contact with each other and yet have increased privacy indoors, and where everyone would have a heightened sense of belonging to a finite, tightly knit universe of their own. While developers elsewhere might try to accomplish some of this with community associations, “swim and racquet” clubs, and meeting places in the nearest drive-to shopping center, Candilis sought to do it through design.

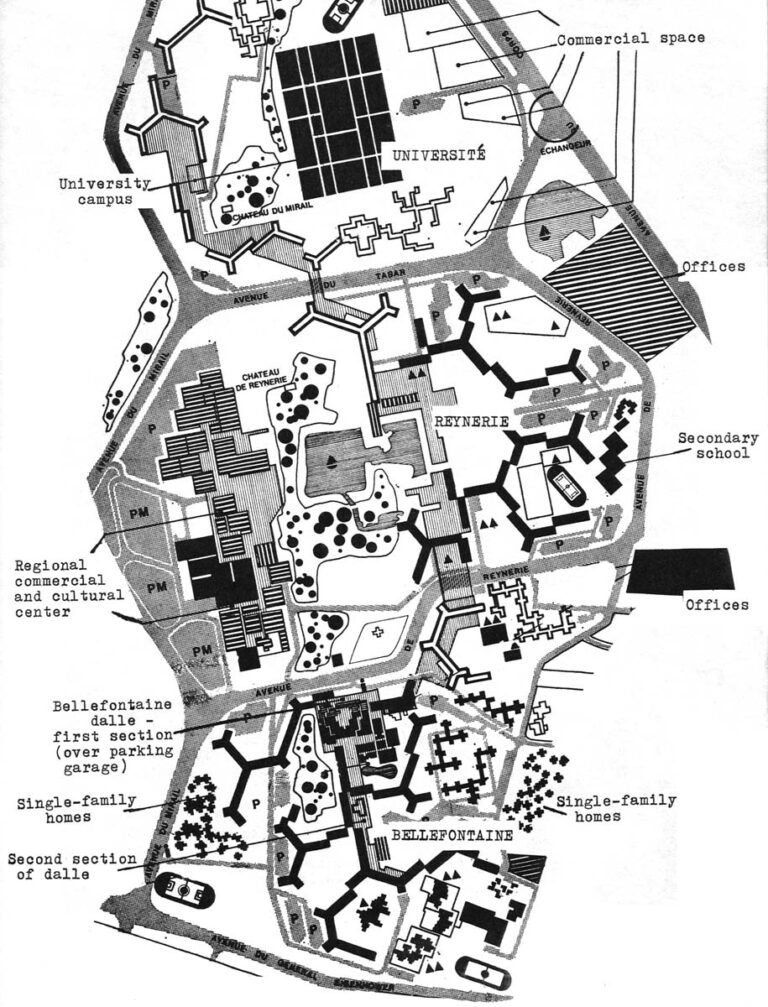

He planned Le Mirail as a huge “T” – two broad strips of essentially linear development with a large regional shopping, cultural and recreational center where they met. The top bar of the T is being built now for 30,000 to 40,000 of Le Mirail’s projected 100,000 population. Three sections, from south to north, make up this initial slice of the project: Bellefontaine, which will have more housing units and secondary schools than the others; Reynerie, to be built around the huge regional shopping center and an adjoining park with a lake in its center, and Mirail-Universite, where the intended focal point, a liberal arts university, is already operating in an old chateau while buildings for it go up a few meters away. Malls like the Bellefontaine dalle, pedestrian bridges over the roads and paths through parks will form a continuous, winding pedestrian boulevard through the three quarters, each of which will have, located along the pedestrian way, its own convenience stores, nursery and elementary schools, social and health center and “Maison du Quartier” recreational and cultural center. A number of businesses, including a huge Motorola plant where electronic components are made and several auto dealerships, are already located on scattered sites on the edges of these sections, so that employees living in Le Mirail could, if they chose, walk to work.

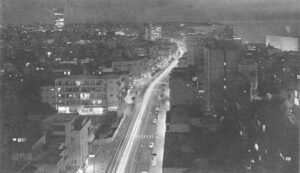

Life on and around the dalle in Le Mirail:

Note in several photos the way sliding panels of loggia constantly change facades of apartment buildings.

Everything has been done to encourage a return to living on a highly urbanized, pedestrian scale, yet alternatives remain for those who want to use cars or live in a single-family home with a garden. It will be possible to drive to the regional shopping center and park in the huge lot beside it and next to the broad ring road, or to walk to it from anywhere in town over the pedestrian malls and through the lakeside park on the other side of the center. The linear pedestrian boulevards of everyday activities are like those of the more recent new towns of Israel, while the regional center, at the meeting point of the convenient ring roads, resembles the shopping center “downtown” of Columbia, Maryland, and other new town projects in the United States.

Does it all work? There are still less than 15,000 people living in Le Mirail so it is early to make final judgments (unless you are a housing official in Paris). The technological innovations – including the combination incinerator-heating plant (which has been duplicated in some parts of Paris), the utility tunnels, the ring roads and underground parking – have preceded incoming residents everywhere and seem to work well. School construction has kept pace with the population, and both teachers and parents have praised the “openness’ of the buildings and classrooms.

The housing itself and some amenities like the Maison du Quartier have been coming along slowly, however, which left the dalle of Bellefontaine a cold and empty island in a sea of mud for months that grew into years. A critical article in the influential Parisian daily LeMonde in the summer of 1970 called Le Mirail “the city of the future that had forgotten the present.” Reports like this and Remy’s, made during the following winter, helped convince Paris-based planners that this wild concrete dream of architect Candilis was obviously unworkable.

But when I saw Le Mirail earlier this year, it had come to life. The Bellefontaine dalle was filled with people. Shoppers streamed in and out of the cluster of stores at the beginning of the dalle, the mothers accompanied by their children who were free to ride their bikes or drag their toys all the way from home up the ramps to where the “big people” were. Children played in a variety of ways all over the different levels of the dalle and the adjacent park areas, and groups of both children and adults came together here and there for a game of marbles or a chat. Although the dalle may be somewhat aesthetically offensive to some visitors (it is certainly no Tuilleries), it is unquestionably functional and durable. Children had turned one concrete deck into a roller rink for the afternoon, and a nearby lawn was being used as a soccer field. A small pool criss-crossed with well-placed stepping stones had been transformed from an idle visual centerpiece into the game’s water hazard. Each child could roam far and wide over the dalle and yet still be under the watchful eye of a parent in an apartment above, some of whom periodically called out encouragement, warnings and scolding from over the sides of their loggias. The gymnasium and the swimming pool were full also on this non-school day.

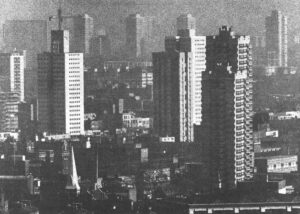

“Streets in the sky” corridors: view of apartments beside a pool, with corridors visible on sixth and ninth floors of buildings (top), and inside corridor (bottom).

One disappointment was the system of “streets in the air” – the Le Corbusier-style outdoor corridors running through and between buildings on the sixth, ninth and twelfth stories. They did not appear to support much activity, perhaps because there was nothing along them but a view of the dalle below, something which is available from the loggia of every apartment.

There is also another, perhaps greater shortcoming. The universe of Le Mirail seemed a bit limited and sterile for adventurous teenagers and young adults who tire of athletic and cultural diversions. There is presently no night life, no places to “hang around” in Le Mirail, and the bus to downtown Toulouse does not yet run often at night. It is not surprising that Remy picked up reports of teenage vandalism and rowdyism, even in so small a population. Movie houses, cafes, teen centers, theaters and hotels are supposed to locate in the regional center, which would be easy enough for everyone in Le Mirail to reach, even on foot. But these facilities require private capital, and private developers have been slow to come to Le Mirail because it is lagging behind schedule overall.

Both Candilis and Bazerque have blamed the delays on indifference and even antagonism to the project on the part of the national government. Le Mirail’s start was delayed four years by the refusal of Parisian bureaucrats to give the plans various approvals needed even though it was not a national government new town project. By the time the project was ready to go, the economic slowdown of the mid-1960s hit the French building industry and, for a long time, forced Le Mirail to survive on the many low-cost housing programs which have financed a major portion of what has been built there so far.

This does not mean that Le Mirail is a public housing project. The French subsidy programs reach up into middle income groups, so that much of Le Mirail’s population are young couples – students, apprentices or beginning workers of other kinds, particularly in the aerospace industries. But it does mean that most of the development has earned SETOMIP Iess return on its investment than expected, limiting its ability to quickly develop such amenities as Bellefontaine’s Maison du Quartier, which was completed well behind schedule, and forcing it to charge private developers higher land prices to pay its mounting mortgage debt. SETOMIP is hoping, however, that the market generated by families in the low-cost housing, favorable local reaction to the community’s innovations and the steady growth of Le Mirail’s industrial areas will soon attract much more private capital.

Perhaps the most thoughtful and accurate criticism made of Le Mirail comes from a planner working on an official French government new town on the edge of Paris. In his opinion, Le Mirail is “too intellectualized” and Candilis is creating too rigid and extreme a version of his vision of urban utopia. Unfortunately, this planner likens Le Mirail to Bijlmemeer, Netherlands, a large government housing project going up outside Amsterdam. Like Le Mirail, Bijlmemeer also makes use of interconnected long, thin, Le Corbusier-like apartment buildings with interior and connecting corridor “streets.” But the buildings at Bijlmemeer, which is being built as quickly and cheaply as possible to relieve a critical housing shortage in Amsterdam, are much larger and more monolithic than those of Le Mirail. And they enclose the kind of lifeless, empty (except for grass and saplings) open spaces that help make public housing projects in the United States so dull. The wealth of community facilities, different levels and variety of the malls and parks of Le Mirail are missing in Bijlmemeer, where auto roads take precedence over the few pedestrian paths and covered corridor “streets,” and parked cars intrude everywhere. Bijlmemeer is no more than a mass housing project; Le Mirail, no matter how radically different it may be from conventional nations of “town,” is becoming a living, almost complete organism.

It would be regrettable if Le Mirail were ignored by the rest of France. The one undeniable strong point of the project is that it has experimented so widely, that so much has been done that developers and government new town planners alike had never tried before. The results of these experiments, whether good or bad, could provide important information for everyone interested in and working on new communities.

Received in New York on May 2, 1972

©1972 Leonard Downie, Jr.

Leonard Downie, Jr. is an Alicia Patterson Fund Fellow on leave from The Washington Post. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Downie, the Post and the Alicia Patterson Fund.