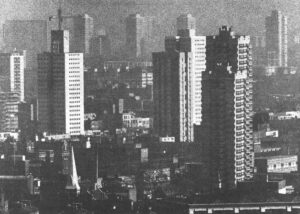

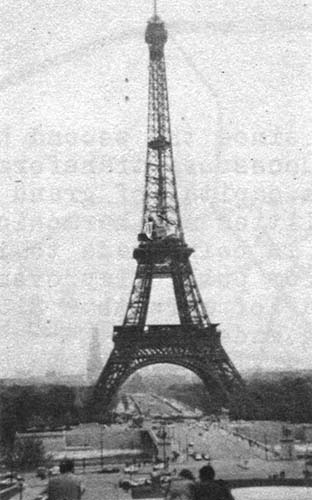

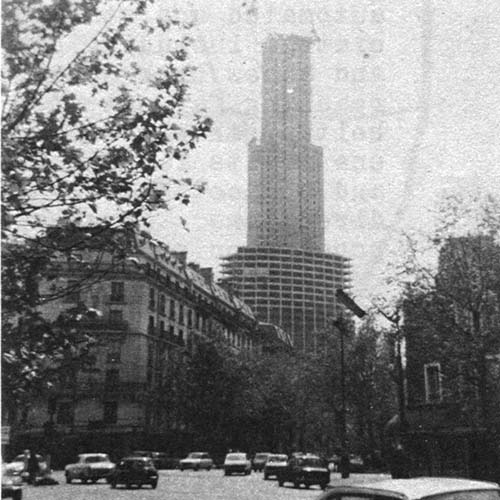

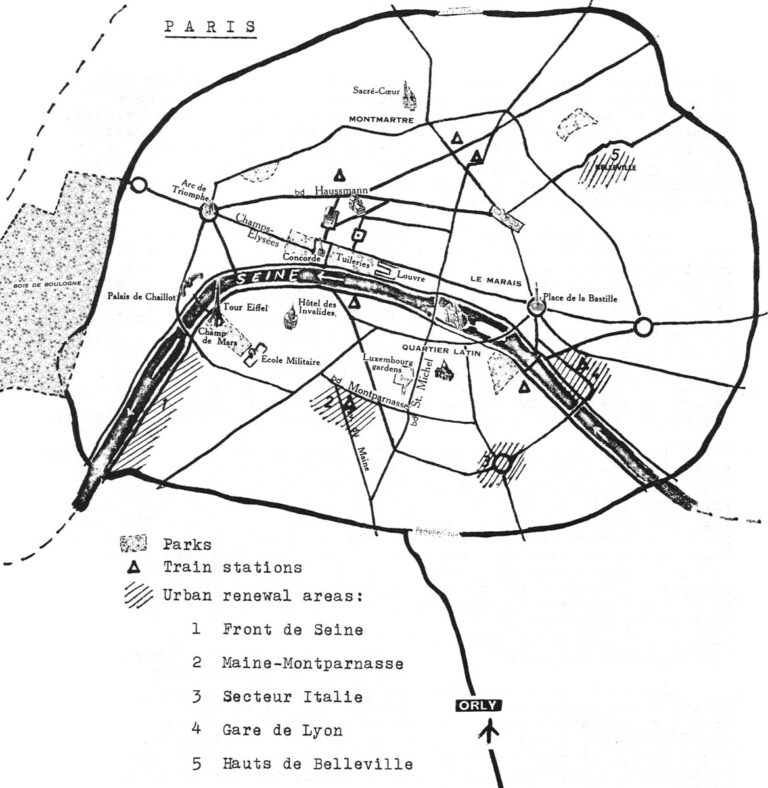

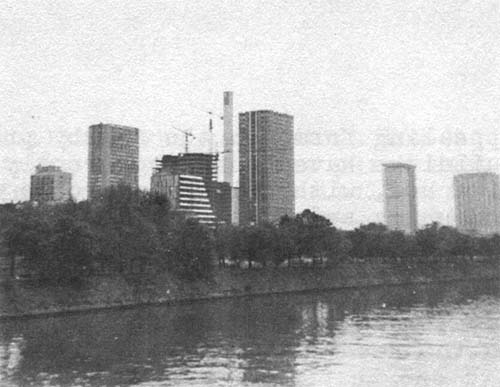

It is not yet in. the guide books, and may never be, except perhaps as a curious bete noire, a grim specter of modern reality rising smack in the middle of the city of everyone’s nostalgia. But it is there, nevertheless, on a level with the Eiffel Tower and the tops of the Invalides and Pantheon domes as one approaches Paris from Orly airport. Inside the city, it pops up absurdly over the lush green treetops of the Luxembourg and Tuileries gardens, pierces the harmonious line of older, much lower and more graceful buildings at the end of one grand boulevard after another, and rises above the squat 18th century Ecole Militaire to peek out from behind the Eiffel Tower in the view of the Champ de Mars from the Palais de Chaillot across the Seine.

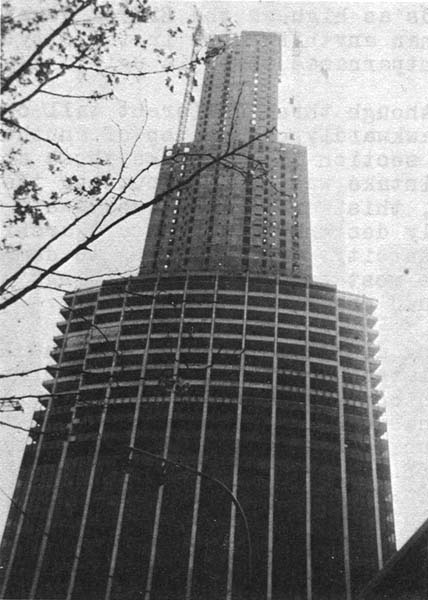

From almost everywhere, it seems, one can see the new Maine-Montparnasse tower, the first true skyscraper office building to go up inside Paris. Although still under construction, it has already risen to most of its planned 60-story, 656-foot height. More than two-thirds as high as the Eiffel Tower (which is 906 feet), it is far taller than anything else in the city. And, on top of that, the Maine-Montparnasse tower is ugly.

It looks as though three different tall concrete buildings had been set down awkwardly one on top of another by some large child. The bottom section is so unlike those above it that it appears an awful mistake was made in putting them all together. From whatever view, this gawky giant overpowers the typically Parisian, delicately designed 19th century architectural set-pieces that fill the city. “It is going to dominate the whole of Paris and crush the most outstanding buildings of our capital with its mass,” complained one French legislator.

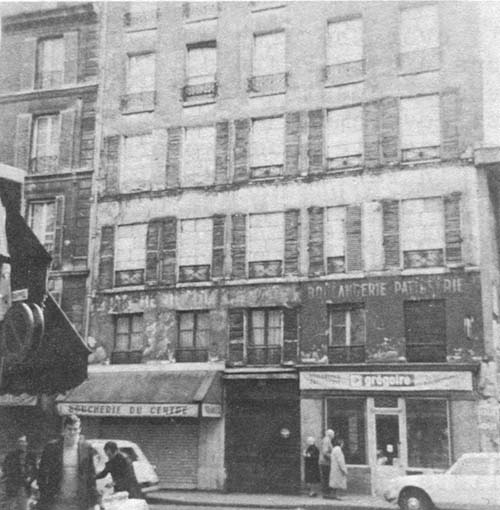

The increasing displeasure here over the Maine-Montparnasse tower is rather belated, however. It will be finished fairly soon, and its realization completes a 30-acre urban renewal project around the Montparnasse railroad station. The tower is surrounded by several more massive but considerably less tall glass-and-concrete boxes containing offices, apartments and the new station. The tower and the project, “Operation Maine-Montparnasse,” are named for two wide avenues that intersect there in the middle of one of the better known neighborhoods of Paris. All the cafes that Hemingway frequented and wrote about in The Sun Also Rises – the Select, Dome and Rotonde – can still be found nearby on the Boulevard du Montparnasse. Operation Maine-Montparnasse threatens to ruin the remaining ambiance of the area, more and more Parisians and wistful visitors are saying now, although few indignant voices were raised when the plans were unveiled a decade ago.

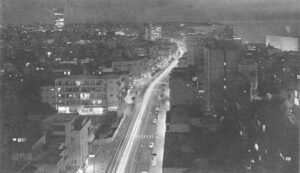

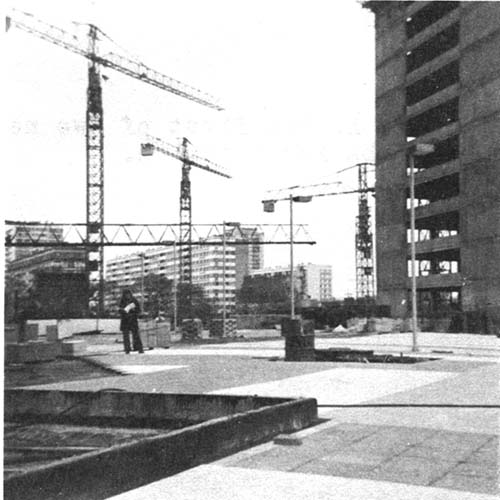

Montparnasse is only one of several areas undergoing “renovation” or urban renewal in Paris. Dozens of new, look-alike, nondescript high-rises, many of the unfinished ones surmounted by giant cranes, have appeared on the banks of the Seine and on altogether too visible hillside sites further back from the river. The well known panoramic view of Paris from the slope of Montmartre is filled with these buildings now; those as tall as thirty stories reach up just over the horizon of the ridge south of the city, and the Maine-Montparnasse tower looms far above them, its angular profile silhouetted against the sky. Controversy is growing over these projects, not just because they are changing much of the face of Paris, but also because their critics say they are upsetting the city’s social composition, population balance and supply of public services. The Maine-Montparnasse tower is symbolic of the belated concern because it is the most noticeable and disruptive of the new construction, and, ironically, because it and the station area project around it have been proudly singled out by the government as showcase examples of a new era of urban progress in Paris.

For the first time since the second half of the 19th century when Haussmann and his successors transformed the city from a medieval maze to a modern capital of grand boulevards, green spaces, unprecedented public utilities and harmonious buildings, a concerted government effort is being made to try to prepare Paris for the future. Much money for public improvements is being spent (an average capital outlay of more than $100 million a year), and radical changes are being made.

The city’s already unmatched subway and commuter train systems are being modernized: several subway lines are being completely automated and stations all over the city are being brightly redecorated, including one with displays of art treasures in the Louvre; and a new high-speed express underground rapid rail network is reaching far out into the suburbs. An American-style automobile beltway that slices through the Bois de Boulogne and tunnels under one of its lakes is being completed around the city’s oval perimeter and connected to new freeways radiating out from Paris in all directions. Five large planned “new towns” of up to 500,000 population each are being developed outside Paris, while the urban renewal projects inside it are replacing hundreds of acres of rundown housing and old warehouses with new buildings. Finally, the entire city’s underground electric and gas lines are being replaced with new equipment, and new incineration, sewage and water treatment plants are being built.

While cities like Rome stand stagnant or those like New York rot away at the core, Paris is making progress and, in many ways, remaining an unusually attractive city in which to live. Although demolition for the urban renewal projects and new private office construction have, for the moment, reduced the population of the city itself from about 2.8 million to 2.6 million (while the metropolitan area has swelled to nearly 10 million), no one is fleeing the central city; instead, prices continue to climb as middle and upper class families compete for housing there. Although one million suburbanites commute to work inside the city each day, three-fourths of them use public transportation rather than private cars. And although much of the city’s outwardly attractive but overcrowded pre-twentieth century housing still lacks central heat, refrigerators, and even bathtubs and toilets in many individual apartments, there is nothing like the hopelessly rundown slums of U.S. cities.

Much of this is the legacy of Baron Haussmann who, as prefect of the old Paris region from 1853 to 1870, redesigned Paris for Napolean III. In planning for new buildings along his airy streets and around the city’s countless neighborhood parks, he had them built with shops and shopkeepers’ homes behind them on the first floors, luxury apartments above them, more modest but roomy housing for families on other levels and the storied garrets for the poor (which included many artists and writers) in dormers at the top. Almost every neighborhood was thus guaranteed the mix of different kinds of people and functions that has served since to set Paris off from many other cities. Paris also became a model of municipal efficiency for the time, with its wide avenues, a sewer system of individually numbered pipes for every street and building and, before the turn of the century, the first lines of the Metropolitain subway (which so fascinated Franz Kafka as a tourist in Paris that he wrote extensively about it in his otherwise sparse travel diaries).

Like his present day successors, Haussmann had his critics too. They said he destroyed too much of quaint medieval Paris, remains of which can be found today only in a few back street areas of the Latin Quarter or the old Jewish neighborhood, the Marais, which is now being restored rather than “renovated.” They also said that his uniform boulevards too often blended into monotony, and that the city’s new monumental scale was inhuman. Much later, it also became apparent that the blight Haussmann had banished from much of Paris was reappearing in its suburbs, especially around the heavy industry that located there. Today, there are several large suburban slums, including scattered bidonvilles, the shanty towns of immigrant Portuguese and North African laborers.

Today, the French government’s ambitious plans for overhauling Paris include both the central city and the suburbs. Inside the city, its objectives are to modernize the housing stock (most of which was built before 1915) and public utilities. Outside it, the five complete new cities – with commerce, culture, recreation, parks and modern transportation of their own – are intended to focus and coordinate what had been helter-skelter suburban expansion. More government-subsidized housing for low-income families is being built both in and around the city, with some of it in the suburbs designated especially for bidonville residents. Much of the improvement in the region’s transportation system is aimed at making the suburban commuters’ journeys into and out of the city more convenient.

Partly to carry out these far-reaching plans, the government of the Paris region was reorganized. Six new local governments (prefectures) were created for Paris and the five surrounding suburban areas, along with a regional prefecture for overall coordination of such functions as metropolitan planning, transportation and new town building. Extra money was then channeled to these entities by the national government, which also appoints the local prefects. DeGaulle personally selected the new planning director for the Paris region, Paul Delouvrier, and charged him specifically with carrying out a modern Haussmann-like “reconstruction” of the city.

As in Haussmann’s time, today’s builders of a new Paris are being accused of destroying too much that has always given the city a special charm. Some critics, led by the Committee to Save Paris, are fighting plans to build a freeway along the left bank of the Seine. There is already one on the right bank, where in some places it replaced what had been pedestrian walks along the river. There are also objections to the tearing up of parks and public squares to build underground garages beneath them. The parks are always reconstructed, but usually with scrawny young saplings where stately old trees had been.

The Committee to Save Paris, made up mostly of wealthy Parisians, is also trying to persuade the government to stop developers from tearing down handsome old townhouses in the prestigious northwestern neighborhoods of the city and replacing them with larger apartment buildings and offices. The official plan for Paris supposedly forbids office construction in those neighborhoods outside the present Champs-Elysees and Boulevard Haussmann business districts, but the new buildings are going up one by one anyway, reducing the around-the-clock liveliness of an increasing number of formerly residential streets.

The loudest controversy, however, is over the city’s extensive urban renewal program. The spring sessions of the Paris city council were frequently dominated by the urban renewal question, and the Socialist Party opposition to the Gaullist government has seized on it as a dramatic example of what it sees as big money government oppressing the working man. Urban renewal in Paris, Socialist leaders argue, is benefitting bankers and developers, who are realizing big profits, and the middle and upper classes, who want more luxury housing and offices with views inside Paris, while it is hurting the working classes, who are being pushed out of their neighborhoods into the suburbs.

The Socialist Party’s anti-urban renewal manifesto is the Livre Noir sur la Renovation a Paris (“black book on urban renewal in Paris”). This thick pamphlet combines anti-capitalist polemics with telling statistics from the government’s own files to reinforce the Socialists’ points. The Socialists say in the livre noir that they have no objection to the improvement of housing in the rather rundown neighborhoods chosen for the urban renewal sites. But they argue that the primary purpose of many renovation projects in Paris has not been to build better homes for the residents of those areas but rather to provide an opportunity for speculators, backed by the big banks, to buy land cheaply and make big profits building and selling luxury housing and offices. The government has helped, they add, by authorizing expropriation of the property of resisting building owners and tenants, and also by providing reassurance for prospective upper class buyers that the projects will rid the affected neighborhoods of all reminders of their previous decline.

As a result, the livre noir shows with statistics, more and more working class families are being displaced inside the city by the middle and upper classes. The Socialists’ charges or “deportation” of the working classes from Paris are not unlike the contention of American urban renewal critics that renovation projects in U.S. cities have too often resulted in the “urban removal” of low income black families. During the 1960s in the Paris region, according to figures cited in the livre noir, out of every 100 wage earners moving out of Paris to its suburbs, 35 were blue collar workers and only 14 were professional or top level white collar employees, while out of every 100 wage earners moving into the city, 34 were upper level workers and only 23 were blue collar (“Blue collar,” a very liberal translation of the French ouvrier or “worker,” here means all lower level salaried workers, including many in government jobs, such as postal workers and policemen.)

Further, the livre noir shows that public and private redevelopment in Paris has so far reduced the overall number of housing units in the city, even though new high-rise buildings are greatly increasing densities in certain individual neighborhoods. Fifteen percent of the housing torn down has been replaced by offices, according to government statistics. And 50,000 more residential units now stand vacant – both in old buildings whose owners are waiting for the last tenants to leave so that they can tear them down, and in new buildings in transitional areas where there is still a high turnover and vacancy rate. (The Socialists also complain that 35,000 other housing units inside the city are owned or rented, but not lived in everyday, by “bourgeois” residents of the suburbs and even distant provinces who can afford weekend second homes in Paris.)

These inequities have also attracted the attention of Gaullist and Communist members of the Paris council. Roger Romani, the council’s member on the city’s commission on urbanism, has warned that the projects are creating an undesirable economic “segregation” of the city’s population. Those being redeveloped by private investors, he pointed out, are providing only high-priced luxury housing, while the far less numerous government-subsidized apartments for low income families are being crowded into separate, much smaller public projects. Romani is also concerned about the high density of some of the new projects, especially those where the population of the neighborhood is being increased two-, three- and even four-fold, and questioned whether public facilities in those areas will suffice.

They probably will not, answered another council member, Lucien Finel, a member of the city’s commission on housing, who reported that both the private and government-sponsored urban renewal projects have been characterized to date by a distinct shortage of community services. Not only is development of promised day-care centers, nursery schools, youth clubs and recreation facilities lagging far behind schedule, he said, but there also are no plans for the provision of additional parks and green space for the increased population densities.

The Socialist Party explains these shortcomings by accusing the government planners and decision makers of being more responsive to big banks and developers than to the public’s desires or needs. It is certainly true that the government has had a habit of keeping its future planning largely hidden from general public view until the last minute, so that there is little time for adverse reaction that might force changes. And it is also true that it is closely allied with the big real estate interests. Much of Paris is already owned by a relatively few big banks, insurance companies and real estate firms, some of which are, in turn, partly owned by the local or national government. Because mortgage lending in France is tightly controlled and generally limited to very short terms (seldom more than six years), only developers tied to one of these major financial powers can tackle a big project. Thus, these financiers and builders are automatically closely associated with government interests, and vice versa. It was no surprise, therefore, that when the former prefect of Paris, Marcel Diebolt, left public life he went to work for a real estate subsidiary of the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas, one of France’s largest real estate investors and one of the more important financiers and developers of urban renewal projects in Paris.

In addition, revisions of French urban renewal law in the late 1950s did violence to a long tradition of rigid protection of private property rights. Today, only a summary proposal from government planners or a private developer is needed before a local government can declare a neighborhood an official urban renewal area and give the project sponsor the powers of a public utility, including the right of eminent domain.

The sponsors themselves range from government agencies to private developers, and are most often combinations of the two. Those projects in which only government-subsidized housing is being built are sponsored by subsidiaries of both national and municipal public housing agencies. In most cases, these subsidiaries are separately incorporated and have as much or more private capital invested in them as they do government money. They sell or rent the housing they build, with some of the proceeds used for payment of a set return to private investors, usually banks. Most of this housing is made available to families qualifying for a variety of government housing subsidies. The most popular is “H.L.M.” for moderate income, working class families, who can obtain low-interest, unusually long-term 30-year loans for home purchases, or who can pay much lower rents for apartments in buildings in which the owner, usually the housing office subsidiary, qualifies for the special loans. There are long waiting lists for this housing.

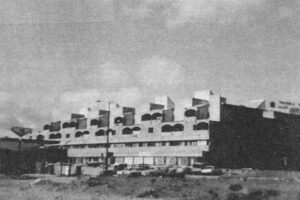

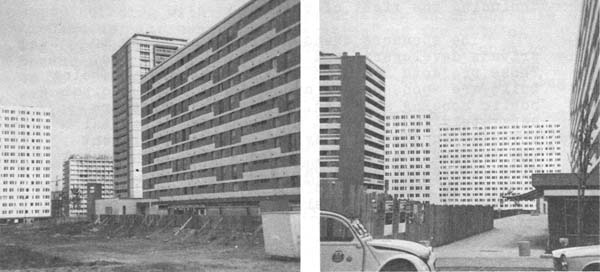

The first subsidized projects were confined mostly to the suburbs of French cities, and ranged from surprisingly attractive complexes of imaginatively designed buildings (including one by Le Corbusier), with balconies and well landscaped grounds, to dense collections of monotonously monolithic high-rises called by the French, in reference to both public and private projects of this type, “grands ensembles.” In some places, H L.M. housing is among the best in the community, notably in Tours, where it is included in a beautiful new riverfront development, and in Toulouse, where H.L.M. presently dominates the exciting experimental new quarter of Le Mirail. In other places, particularly in several Paris suburbs, H.L.M. and similar projects, despite the undeniable improvements in interior comfort that they provide their residents, have become synonomous with much that is undesirable about French suburbia: rows of nondescript high-rises on a sparse landscape with few facilities or even stores for their occupants.

It is a significant step forward that very much of this subsidized housing is being built inside Paris at all. But unfortunately too little of it improves much on the appearance or amenities of what has been done in the suburbs, and this housing has been isolated in separate projects from those in which housing for higher income families is going. This is the case with one crowded project of public housing that is nearing completion almost directly alongside the city’s largest predominantly private urban renewal area, Secteur Italie, south of the Latin Quarter. It is being financed by a subsidized housing entity controlled by the city of Paris and the private Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas. This project is an obviously compromised version of contemporary European apartment design, which can be seen in fuller, more appealing forms in the nearby private development. The subsidized buildings have been incoherently mixed together and left, for some time now, with only muddy voids where recreation facilities and community services were to be located. Although the first new housing was completed here more than ten years ago, work on the public facilities has been deferred until now, after the last building has been finished. Even when these facilities are completed, they will, if the plans are correct, be scarcely equal to the needs of the project’s many residents.

A larger share of the renovation of Paris is being carried out by public-private societes d’economie mixte, whose investors include government agencies, banks and private developers. A frequent partner in these ventures in Paris is SAGI, the Societe Auxiliare de Gestion Immobiliere, which itself is owned half by the municipality of Paris and half by private investors, and which owns more than 20,000 housing units in the city. A different societe d’economie mixte is formed for each project, and each is also vested with the powers of a public utility, including that of expropriation.

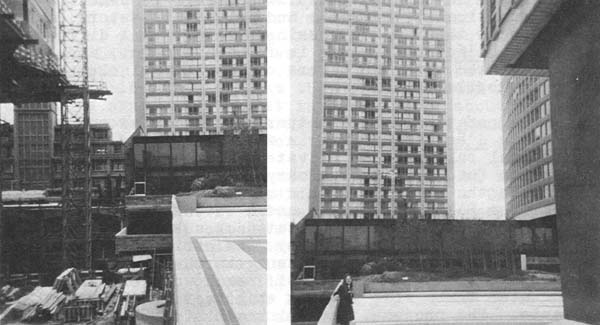

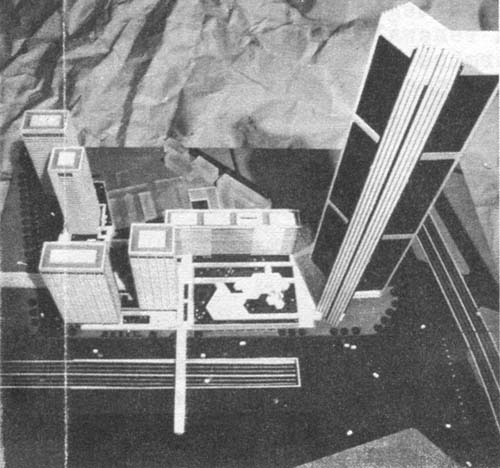

Operation Maine-Montparnasse is being carried out by a societe d’economie mixte in which the city of Paris, the French national railroad and private banks, insurance companies and pension funds are the primary investors. Its purpose is both to provide the railroad with a modern new station for trains that run from Paris to suburbs and provinces to the south and to take advantage of this transportation hub (four subway lines also intersect at the station) by locating new offices and apartments there. Many suburban residents working in the one million square feet of already completed offices can reach work on one short commuter train ride without ever setting foot on the streets of Paris. The project, including the Maine-Montparnasse Tower, which has been sold off floor by floor in advance, has been an unqualified financial success despite its lack of aesthetic appeal. Once again, however, its developers have so far failed to keep promises to provide additional green space. Following sharp criticism from members of the Paris council, city officials are now talking vaguely about public gardens on a raised concrete deck that will connect the tower, when it is finished, with several of the project’s other buildings.

Another project of this kind is the larger (72 acres) Operation Front de Seine, being developed by a societe d’economie mixte dominated by the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas along the left bank of the Seine from near the Eiffel Tower southwest to the city limits. Automobiles once had been manufactured, repaired and warehoused in this area. After private developers gradually bought up rundown housing in the surrounding neighborhood, tore it down and put up a variety of new luxury apartments, it was decided to build a more cohesive group of much taller apartments and offices along the riverfront.

“Operation Front De Seine”

City officials are particularly proud of the plans for Front de Seine. All parking and many of the streets, including the planned freeway along the bank of the Seine, are to be located under a massive raised concrete deck for pedestrians that would connect many of the new buildings with each other, and extend all the way to the river, where it would resemble a giant balcony jutting out over the freeway on the quai.

Several different private developers are involved in Front de Seine and the buildings range from very imaginative in exterior design and interior practicality to uninteresting, maximum-profit high-rises of the standard mold. Not all of the project, apparently, will be linked to the raised concrete platform, and plans to extend it to the river are still uncertain financially and, for the moment, entangled with the freeway question. Moreover, the project does not merge smoothly with the neighborhood around it; its massive buildings and raised pedestrian levels butt sharply up against smaller scale buildings, new and old, in their less dense park-like settings along conventional ground-level streets and sidewalks.

The two biggest urban renewal projects in Paris are privately controlled and have caused the most controversy. One of them, located on high ground in a northeastern neighborhood of Paris, is called Les Hauts de Belleville. Here the government granted a concession to a private developer, SPEI, a subsidiary of a giant French real estate company that has built many large housing developments in Paris and its suburbs, as well as summer home communities and ski resorts throughout France. Land prices were especially low in this once forgotten, formerly working class area, and classification of the area for urban renewal gave SPEI the power to seek condemnation of land that it could not buy at prices it offered.

SPEI is developing mostly big-profit luxury housing in Belleville, although some H.L.M. (subsidized housing) is to follow (too late, though, to provide homes for most of the working class families forced to relocate when demolition began five years ago). The deal struck there and in other urban renewal projects calls for private developers, in return for permission to put up high-rise buildings, to donate some of their land and profits to the city for subsidized housing and community facilities. Although more than 4,000 new housing units are being built in Les Hauts de Belleville where only 2,000 had been before, and 1,200 of those units are already finished, none of the public facilities required by the government – including a library, youth center, day care center and clinic – will be built before 1975.

SPEI is also the biggest developer in the other, much larger privately controlled urban renewal project, Secteur Italie, which covers 270 acres around the Place d’Italie, south of the Latin Quarter, where several roads into Paris converge. Here was a large lower class residential area where land prices also were unusually low for Paris, especially since several small enclaves of subsidized housing had gone up around it during the past two decades. Big profits could be made if only a redevelopment project could create a large, inviting island of affluence in an area otherwise quite unattractive to middle class apartment buyers. It was a perfect opportunity for speculators.

Officially, however, Secteur Italie is something new in French urban renewal – not a government-run project nor the imposed development of large private speculators from the outside. Instead, the developers were to draw up the redevelopment plans and present them to owners of property in the area. Once three-fourths of the owners had agreed to go along with the project, the resulting federation could expropriate the land of holdouts at fair prices. In reality, however, as the Socialist Party’s livre noir has pointed out, the developers began by quietly buying up much of the land themselves in the names of straw parties in order to be certain that their plan would be approved. And since they had bought the land themselves, cheaply and quietly, the windfall profits would be all theirs.

Nevertheless, a federation was formed and given authority by the government to go ahead. In a neighborhood where 22,000 mostly lower class residents had lived, 60,000 mostly middle class people will be moved in. About 10,000 housing units have been demolished, to be replaced by 19,000 new ones, the vast majority in luxury high-rise buildings. Less than 3,000 of the new apartments will be H.L.M. There will also be several office buildings, the biggest shopping center to be built inside the city limits, and the kind of private recreation facilities (ice skating rinks, gymnasiums, tennis courts and indoor swimming pools) that are usually associated with suburban swim and racquet clubs. “Help restore Paris to Parisians,” urges a slogan in the promotional literature and advertisements, apparently intimating that the “real” Parisians are the bourgeoisie the promoters are trying to attract and that all those working class families had merely been interlopers.

The two largest complexes in Secteur Italie are being built by SPEI. One, called Galaxie, is a fairly conventional collection of luxury high-rises around the big shopping center, much of which will be below pedestrian level. The one unusual building of Galaxie is another planned 60-story tower, to be called “Apogee de Paris,” which has not yet been finally approved for construction by the city. Galaxie advertises, for those still wary of the surrounding neighborhood, that because of the shopping center and other services, “you never have to leave Galaxie.”

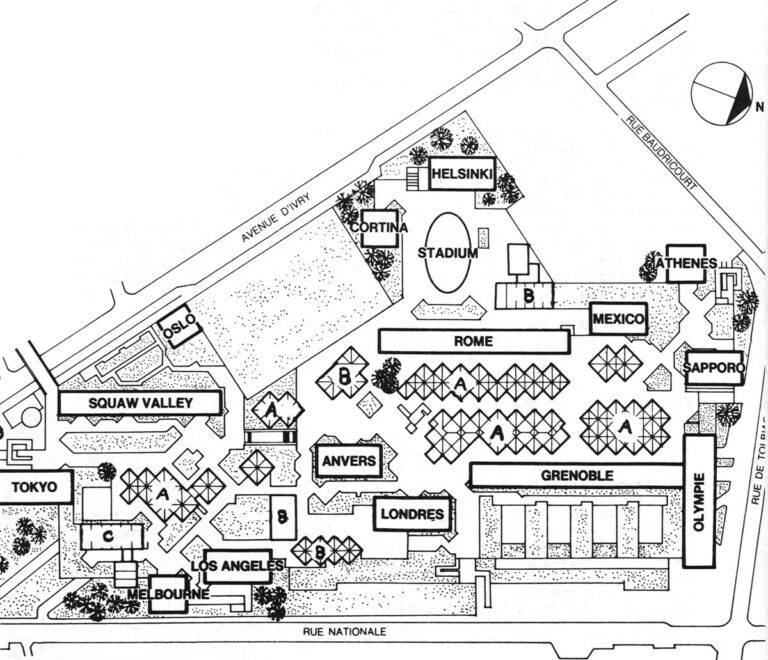

The other SPEI project is called Olympiades, and each of its luxury high-rises is to be named for a different city in which Olympic games have been held: “Grenoble,” “Sapporo,” “Rome,” “Helsinki,” “Tokyo,” “Melbourne,” “Squaw Valley” and so on. The theme here is recreation, modeled consciously, SPEI says, on American country club communities, but in an urban setting. Twenty different kinds of sports activities, most of them of the indoor variety, will be available in its “covered stadium” (actually a huge gymnasium) and natatorium complex. Of more genuine interest is the project’s raised concrete pedestrian deck, which is to run from one end of it to the other, covered with shops, a supermarket, a library, day-care centers and other community facilities, as well as the entrances to the recreation center. It would be much more extensive and lively than the pedestrian deck planned for Front de Seine; in fact, it may compare, on a much smaller scale, to the experimental dalles of Le Mirail at Toulouse. Le Mirail: A Study In Concrete(See LD-7, Le Mirail: A Study in Concrete.)

Although several buildings are completed or under construction and the concrete deck has been begun, there is no assurance of just what facilities will eventually be provided or when. SPEI and other developers in Secteur Italie are so far behind in their commitments to provide school buildings and community centers for the 2600 housing units already completed that one member of the Paris council, Andre Voguet, has proposed that the city government announce to the public that, “It is necessary to inform citizens who wish to buy or rent in the Secteur Italie renovation area that they are being deceived… (by) the absence of facilities that they were assured of…”

Not only these public facilities are in short supply in the new neighborhoods, but so too, in comparison to the dense populations of these high-rise clusters, are such traditionally Parisian amenities as neighborhood stores for every daily need, a cafe on every corner and a nearby park with enough benches and room in the sandboxes for everyone on a sunny Sunday afternoon.

In general, the urban renewal projects inside Paris are, more than anything elses pedestrian. The housing itself is a decided improvement on what had been in these neighborhoods before and certainly will not stand empty. But the architecture, by and large, is hopelessly bland, and in some places over-poweringly ugly, especially for Paris, where one expects better and where so much of unusual character for a big city is now threatened. In addition, too many of the serious social mistakes of urban renewal in American cities – social sterility, economic segregation, excessive population density for the level of public services, and a dearth of useful green space – are showing up in one project in Paris after another. With the exception of the sudden popularity of raised concrete decks, there is none of the experimentation in new urban forms that has characterized inner city rebuilding projects in Scandinavia, Holland, Germany or England, among other countries, since the end of World War II.

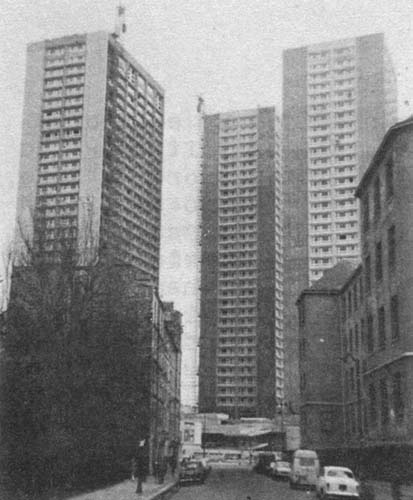

“Secteur Italie”

From left to right, the “Sapporo,” “Mexico” and “Athenes” apartment towers in Secteur Italie (far right on plan below).

Plan for “Olympiades”: (A) stores, (B) nursery schools and day-care centers, (C) library. All are scattered on raised concrete pedestrian deck connecting the apartment towers. (SPEI drawing)

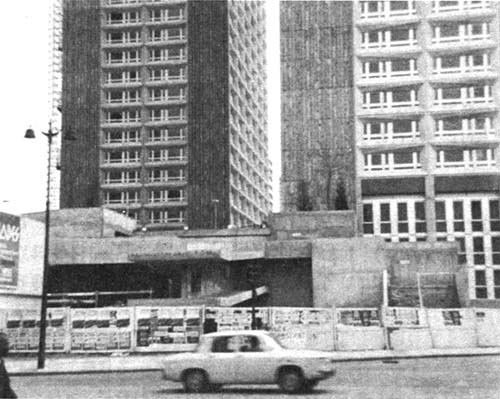

The raised concrete pedestrian deck of “Olympiades”: seen from front.

These shortcomings can be blamed in part on the inability of the French government to match ambitious plans with sufficient public money to carry them out. When public resources became strained by the many renovation projects planned for Paris, Georges Pompidou, who inherited the program from Charles DeGaulle, urged private investors to share more of the burden. To make it as profitable as possible for them, they were given larger shares of the public-private corporations, as well as such concessions as permission to build more lucrative high-rise buildings and to defer development of public facilities.

It was a gamble that France may eventually regret. Even after his political and ideological biases are discounted, Communist member of the Paris Council Maurice Berlemont may have summed it up best when he said that, since Pompidou opened his arms to private real estate investors, “the banks have found a way to maximize profits and exert the predominant influence at the heart of the societes d’economie mixte, and the antisocial character or urban renewal has been increased.”

The participation of private investors in urban renewal does not have to be detrimental. Elsewhere in Europe, it has not held back innovation; negative effects have materialized only when permitted by government officials. The French government deserves credit for many of the bold initiatives of its rebuilding program for Paris, but at the same time it must be blamed for wasting much of a golden opportunity to improve on what Baron Haussmann had done and to continue his quest for urban excellence, rather than to allow expediency and the narrow goal of maximum profits to hold sway.

This is the first of two newsletters on new urban development in the Paris region.

Received in New York on May 23, 1972

©1972 Leonard Downie, Jr.

Leonard Downie, Jr. is an Alicia Patterson Fund Fellow on leave from The Washington Post. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Downie, the Post and the Alicia Patterson Fund.