Paris, France

May, 1972

To get to Parly 2, one drives west of Paris and through a short stretch of typical French countryside almost to the edge of the thick forest of Versailles before turning down a road that opens abruptly onto U.S. suburbia. There, grouped around a large enclosed shopping center and its surrounding parking lot are acres of identical modern three-story walkup apartment buildings interspersed with swimming pools, lawns and small playgrounds. The shopping center is a covered, air conditioned, two-story rectangular mall with a big department store at each end, rows of smaller shops and boutiques along the sides, and a few kiosks and snack places, as well as an indoor fountain and decorative pool, in the middle. Americans familiar with any of the scores of similar centers in the United States might well feel more at home at Parly 2 than in the U.S. Embassy in Paris.

It is still a new concept in France, however, and developer Robert de Balkany, who is also building several other apartment projects and shopping centers around Paris, is marketing Parly 2 as the future style for French living. To emphasize this, he originally named the development “Paris 2,” but Paris region officials forced him to change it, so he chose a close-sounding substitute. There is no Parly 1.

There seems to be no doubt that the Parly 2 concept is quite attractive to many Parisian suburbanites. Its apartments have all been sold from blueprints before the buildings were finished, and the shopping center’s sales have steadily increased by 20 to 30 percent every year. In quite a different way, Parly 2 has also been recognized as an important sign of the times by French filmmakers, who have gone there often to make movies about the new Paris suburbia and the marital and social problems supposedly spawned by boredom and alienation there.

Altogether, more than seven million people now live in the suburbs of Paris – nearly three times the population of the city itself. Only recently has anyone in Paris become interested in how they live – be it in de Balkany’s assured version of the future or the filmmakers’ alarmed visions of the Brave New World. A survey taken recently by a reporter for the newspaper Le Monde in the busy Saint-Lazare station, through which tens of thousands of rail commuters arrive in Paris each day, indicated widespread contentment among the suburbanites interviewed. Most of them were coming, however, from the preferred western suburbs, where there are large single-family homes with gardens and well-equipped modern apartments with swimming pools.

Elsewhere outside Paris, particularly to the north and east, are the slums that had been pushed out of the city along with the factories of heavy industry. Old industrial suburbs have become overcrowded and rundown. Decrepit shanty towns have been put up by immigrant laborers. And stark slab apartment towers built cheaply for the poor with government subsidies have begun falling apart after a decade or two of hard use. Not only do these areas suffer from all the deficiencies of deteriorated communities everywhere, but they are also cut off by location, overloaded roads and inadequate public transportation from the resources of the city.

Further out, sprouting almost everywhere in what had been until recently rural countryside, are scattered subdivisions of apartments, rowhouses and Levittown-like single-family homes being built by Frenchmen like de Balkany and American firms like Kaufmann and Broad of California and Levitt and Sons. Although they are providing badly needed modern housing for the Paris region, too many of these helter-skelter developments, like their equivalents in the United States, also suffer from transportation problems, a dearth of community services and recreational and cultural activities and little sense of identity as communities. It is significant that de Balkany, to combat this last shortcoming, decided to use Paris place names at Parly 2, giving the various sections of the shopping center parking lot, for instance, labels like “Opera,” “Concorde” and “Eiffel.”

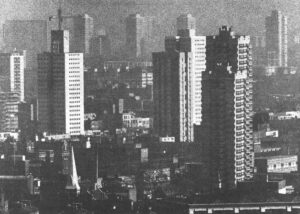

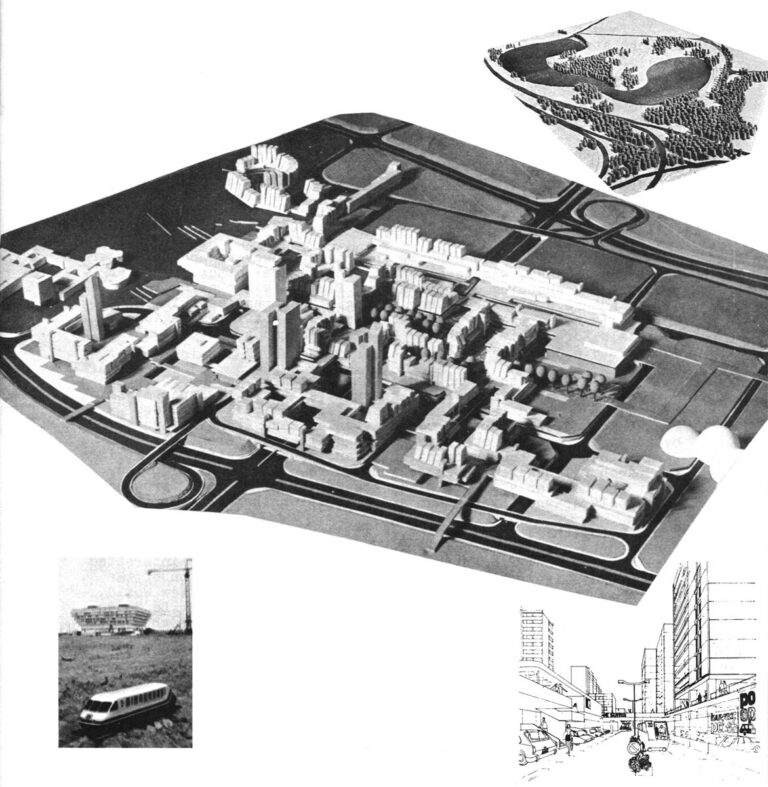

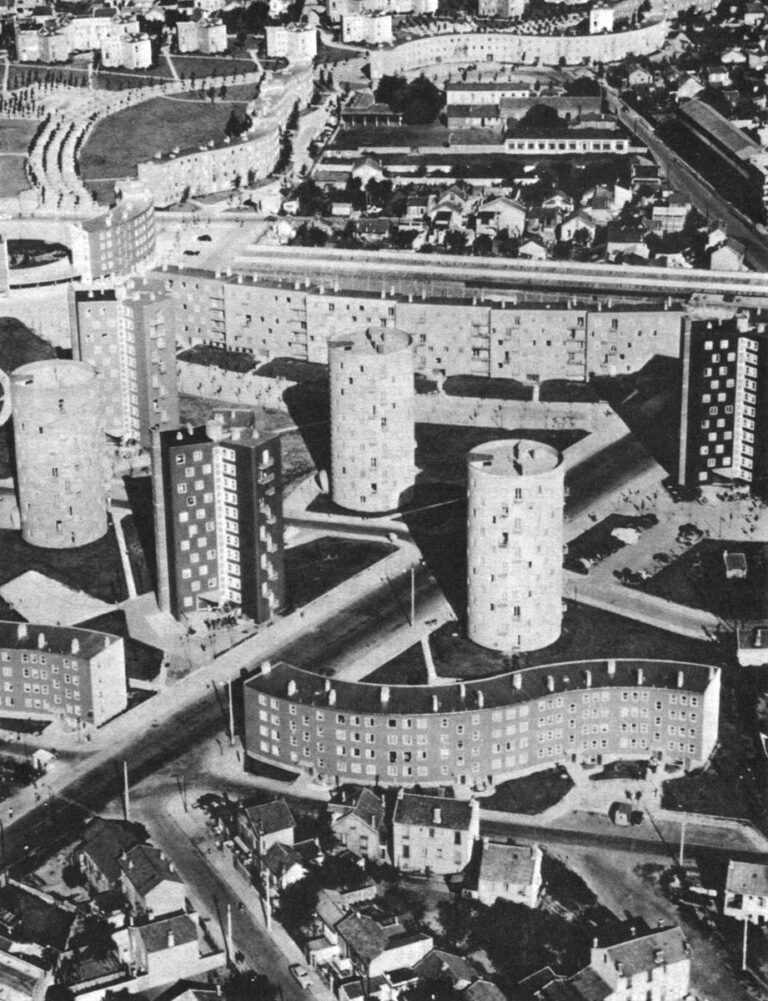

In attempts to improve the suburbs and alleviate the continuing shortage of decent housing for low-income families, the French government joined with private investors in recent years to develop a few large projects on low-priced suburban land. Most of the housing in these grands ensembles, as they came to be called, consisted of apartments constructed with advanced French mass production methods and sold and rented to families qualifying under various government subsidy programs. Because of the haste with which their first stages were designed and built, some have turned out to be nightmares of the unrestrained imaginations of their planners. In one, the 420-acre Sarcelles project being built for 50,000 people just beyond factory suburbs north of Paris, monolithic rows of huge apartment towers line the grid pattern of streets running from the main highway to a station on the railroad. In another, Bobigny, northeast of Paris, the buildings are shaped like giant cylinders, stars and unfurled ribbons and have been strewn in a hodge-podge on a bare wind-swept site bordered by little single-family homes.

These projects do, however, provide much better housing for their working class tenants than had either the nearby industrial slums or earlier government developments. Along with the apartments this time have come some green spaces, conveniently located stores, community services and stations on the commuter railroad lines. In Sarcelles and Bobigny, there are also businesses that employ some local residents, with more coming in the future. A new regional commercial and office center with underground parking, a central pedestrian mall and more imaginative housing groups around it is being built in Sarcelles and a similar addition is planned for Bobigny. The public-private corporations that own each of them are now promoting the two developments as “new towns.”

They certainly are fast-growing new communities that differ greatly from what is around them, but neither one fits the European definition of a new town as an advanced, cohesive form of the urban unit. The latest phase of Sarcelles will fit with what was built before it about as well as the whole project merges successfully with the little old buildings of the country village of Sarcelles that the new development has overrun. It still lacks much of the cultural, recreational and other facilities of a successful city, yet it already suffers from traffic congestion, soil erosion and blight. Trampled lawns and badly rundown buildings less than ten years old, which give the appearance of ready-built slums, show Sarcelles to still be, basically, an overtaxed housing project.

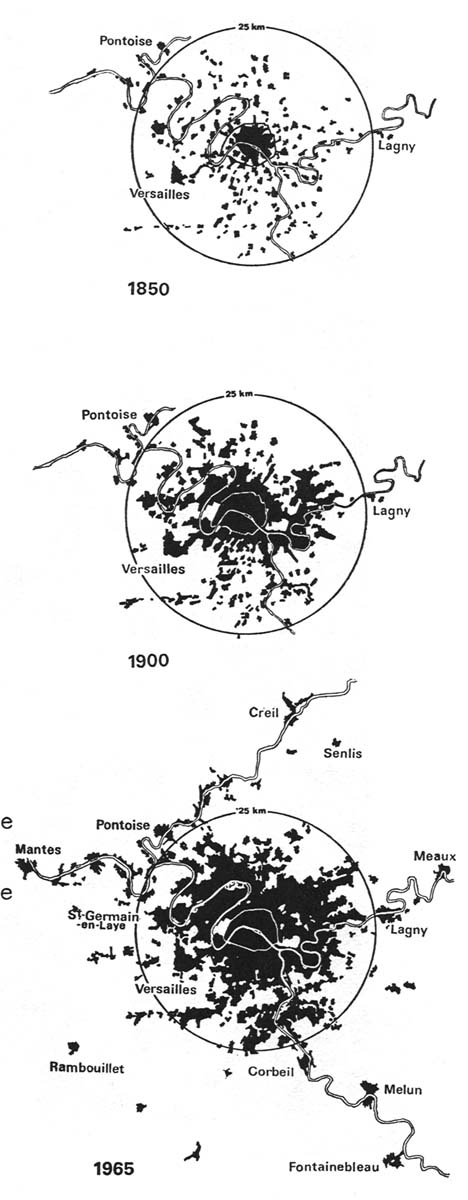

It should be remembered, though, that Sarcelles comes much closer than much of the rest of the vast suburban region of Paris to being a complete community. The privately built subdivisions, for instance, provide far less for their residents, and are so widely and incoherently dispersed, with developers leapfrogging (as they do in the United States) over higher priced ground from one cheaply acquired tract to another, that there seems to be no way to pull them together to share costly facilities or solve mutual problems. Meanwhile, many formerly isolated little towns within commuting distance of Paris, which had long preserved their individual identities, have, like old Sarcelles, suddenly gained big, noisy next-door neighbors with little or no compensation in the form of desirable big city services. The unchanneled growth has also threatened to despoil forever the scenic river valleys and forested plateaus with which the Paris region was endowed.

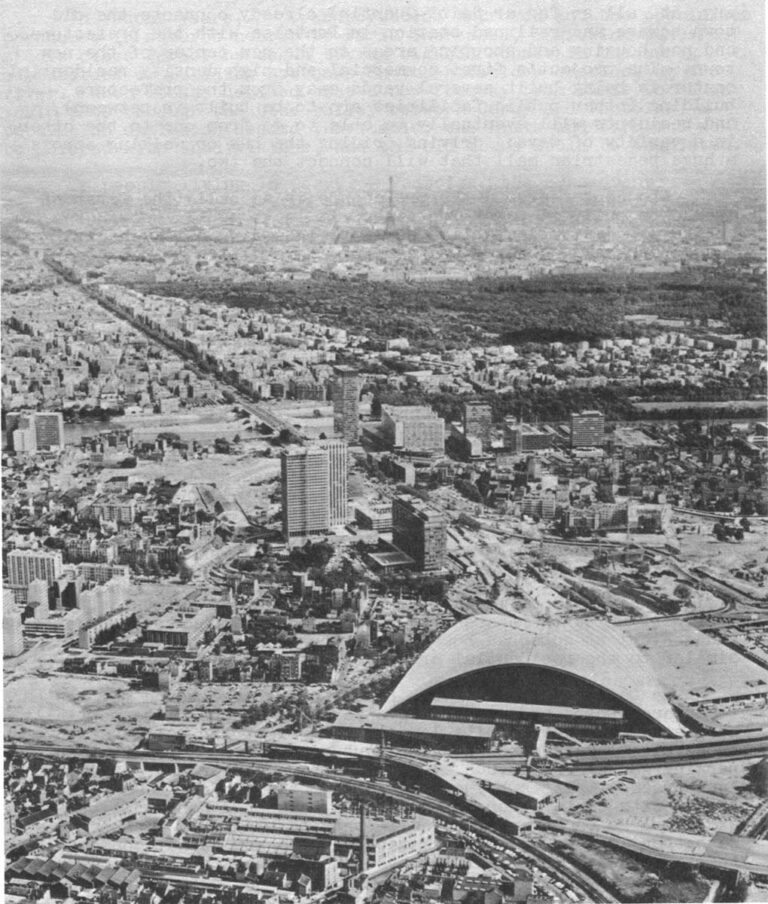

When it finally came France’s turn to consider development of planned new towns like those already in existance or under construction in other European countries, the suburban sprawl already was widespread. So planners in the Paris region decided to use the new town concept to reorganize the city’s suburbs, provide them with more of the necessities and advantages of urban life, and prevent them from overrunning important nature areas. This planning was begun a decade ago as part of the present metropolitan modernization of Paris by Paul Delouvrier, appointed by then President DeGaulle as the first head of the new regional planning and governmental unit of the Paris metropolitan area (See LD-8, Paris: Under Construction).

Delouvrier did not want to build dependent satellites like the suburb-towns of Scandinavia or the “garden city” suburbs of London because he feared they would still be too small to support sufficient urban facilities. And he did not believe that Paris itself could supply these facilities for 10 million people. So Delouvrier decided to organize groups of existing suburbs and the gaps of open land between them into new cities with built-up “downtown”-like urban centers. Each new city was to have its own internal transportation system, good public transportation to and from Paris, a full range of commercial, cultural and recreational activities, large public parks, comprehensive health and welfare services and educational institutions. They were also expected to experiment with ways to solve such nagging urban problems as separation of pedestrian and auto traffic, waste disposal, water supply and soil conservation. Each new city would house as many as 500,000 people on about as much land as there is inside Paris, where 2.5 million people live. Much of the difference in density is attributable to the large open spaces to be left protected in the new towns. Delouvrier insisted that the new cities have a lively, pleasing urban atmosphere of the kind that has always been characteristic of Paris. “Of course we cannot give them all a Comedie Francaise,” he once said, “but we will try to give them everything else.”

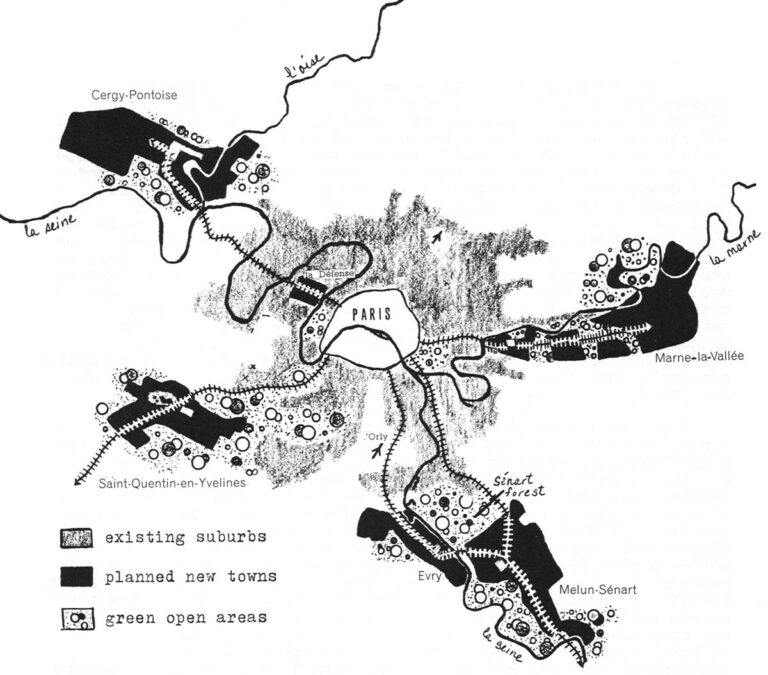

After long consideration, five new town sites were selected in the suburbs around Paris: Marne-la-Vallee, the relatively undeveloped valley of the Marne River directly east of the city; Melun-Senart, in an old, rundown suburban area southeast of the city that particularly lacks adequate public facilities; Evry, in an area especially ripe for rapid, otherwise uncontrolled growth on a freeway and rail line south of Paris and Orly airport on the west bank of the Seine; Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, a group of already fast-growing suburbs beyond Versailles southwest of Paris in a corridor of traditional suburban growth dating back over 300 years to the court of Louis XIV; and finally, Cergy-Pontoise, in the beautiful and commercially exploitable Oise valley northwest of Paris, where suburbanites had begun to swell the venerable old river towns of Cergy and Pontoise. Each site had already been invaded by suburban subdivisions; yet each also has enough vacant land left for planned new growth, public uses and experimentation.

The new cities were to be arranged along two parallel axes running from southeast to northwest on the top and bottom of the Paris region, roughly following the flow of the Seine and its tributaries toward the sea. In this way, the projects could take advantage of the river valleys’ water and scenery and, at the same time, protect them with carefully planned growth and park development. Laws were passed to conserve the woodlands remaining in the Paris region so that they could be kept as wild open spaces in and around the new cities. Improved rapid rail transportation, including both relocated and modernized commuter train lines and extensions of the Paris metro system, are to run through each new city and its center. The new towns would be exempt from the high penalty taxes that businesses now must otherwise pay to locate in the Paris region (part of a national policy to ease pressure on Paris and revitalize the economies of other parts of the country), so that they could attract sufficient (non-polluting) business to make them financially successful and provide close-to-home jobs for those residents who want them.

To facilitate development of the five new towns around Paris, along with others outside Rouen, Lille, Lyon and Marseille, a national government inter-ministerial committee on new towns was formed with representatives from the finance, interior affairs, housing, education, sports and recreation, cultural affairs, environmental protection, industrial development, transportation, public sanitation, and post office and telephone ministries. This committee drew from the budgets of each affected ministry funds earmarked especially for such new town needs as subsidized housing, utilities, highways and public transit, schools, and recreation and cultural facilities. For the new towns around Paris, the national officials’ counterparts in the Paris regional government were added to the inter-ministerial committee to make decision-making faster and more direct. A special independent regional agency also was formed to channel, and account for, government aid to the Paris new towns.

The national government promulgated new laws and regulations that enabled the prefecture of the Paris region, with specific approval in each case from the national executive, to designate locations for the new towns and send in study missions of local and national planners to set boundaries for the projects and make preliminary plans for their development. All land within the perimeter drawn by the study mission at each site is then immediately frozen by the government, and regional and national agencies begin buying tracts that the mission designates for the new town’s urban center and surrounding new development.

Once the projent’s general plans are approved, the study mission is succeeded by an “etablissement public,” a public corporation run by seven representatives of the national inter-ministerial committee on new towns and seven officials of the Paris region and the suburban municipalities with territory inside the new town’s planned perimeter. The etablissement public makes all final decisions on how the new town will be built, uses borrowed national government money to take over the land that had been bought by other government agencies and to buy up the rest that is needed, and then sells land to housing developers and businesses to help finance the various public improvements. The housing, offices and factories put up by developers and businesses must conform strictly to etablissement public directives on location, density, required amenities and the like. Architectural design, the actual construction and sales and rental of what is built is left up to the developers, many of whom are public-private corporations that build subsidized housing for lower-income families. The etablissement public itself builds the urban center of stores, offices and public facilities and rents out the floor space.

Some public improvements in the new towns, like highways and primary water and sewer lines and treatment plants, are paid for entirely by the regional and national governments. Others, such as schools, libraries, recreational and cultural facilities, and train or subway stations, are partly subsidized by government ministries (and the national railroad and Paris metropolitan subway authority), with the new town itself responsible for making up the rest out of land sales by the etablissement public and local taxes to be collected from the new town’s residents. At the beginning, the new town is provided by the national government with a pro-rated share (according to its planned future population) of the national tax revenue returned to localities, even though it does not yet have the necessary number of residents to qualify for it.

The planned perimeter of each new town takes in all or part of the political territory of from one to three dozen existing communities, ranging from tiny old rural villages and larger towns to collections of booming new subdivisions. The designated land will become part of the new town whether the affected communities like it or not. They are given the choice of joining in the development of the project and contributing proportionately to the cost of its public improvements, with the right to share in its tax revenues later, or of simply giving up the designated area to the new town and having nothing further to do with it.

One advantage to the relatively late start France is making in new town building is that its planners can learn from the successes and failures of what has already been tried elsewhere. In the plans completed so far for the Paris projects, one can see the influence of the regional rapid rail transit system that ties central Stockholm to its several new town-suburbs, the forms of the densely built-up centers of the new towns of Sweden and Germany, the economic success of suburban shopping centers of the United States, and the planning and financing methods used in new town building in Great Britain. One disadvantage, however, is that instead of being able to do what they please with large tracts of virgin land, French planners must cope with problems arising from the existing patterns of suburban growth around Paris.

One of these problems is the disadvantaged development of suburbs to the east of Paris. The western part of the city has always been considered more fashionable. Wealthy Parisians live there and in the closest western suburbs, while the middle class has pushed out to the countryside further west in established towns like Versailles and new developments like nearby Parly 2. In recent years, stores including branches of those in Paris, light industry and business offices, as well as the few public and cultural facilities made available to the suburbs, have followed the middle class migration to the west. The areas to the northeast, east and southeast of Paris were left with heavy industry and housing for those people who could not find or afford it elsewhere. Most of the government-subsidized housing built for low-income families in the suburbs also has been located there. And the worst slums have grown up in and around the old factory towns northeast of Paris.

As far as is possible, the two new towns to be built east of Paris, Marne-la-Vallee and Melun-Senart, are supposed to bring to this area transportation and public services it now lacks , better housing, more jobs (especially for middle class workers) and large new commercial, social, recreational and cultural centers. They also are to conserve and yet make available for public use the area’s neglected outdoor spaces, particularly the Marne River valley and the 7,000-acre Senart forest.

In selecting sites for the eastern new towns, the regional government skipped over the dense, rundown, heavily industrialized suburbs northeast and southeast of Paris, where there is no longer enough usable vacant land and where earlier government housing projects like Sarcelles and Bobigny are located and are being improved to some extent. The planners turned instead to the less developed high ground on the southern bank of the Marne, due east of Paris (Marne-la-Vallee), and the eastern bank of the Seine, far south of the city (Melun-Senart).

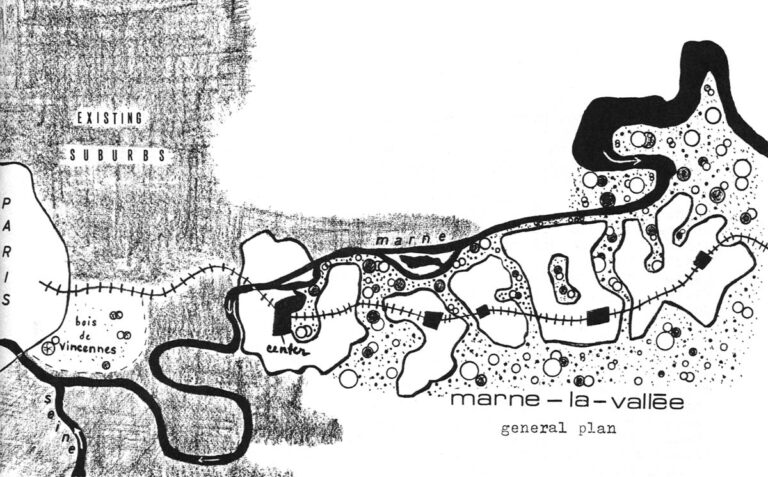

Planning for Melun-Senart has only recently begun, but that for Marne-la-Vallee is much further along and proposes some ingenious ways of coping with particular problems facing the project. The site is a narrow, 13-mile-long series of hills flanked by the river valley to the north and a green plateau of forests and farms to the south, both of which are to be protected from further encroachment by development. The area’s present roads are inadequate and the nearest commuter railroad line runs along the river below to a town east of the Marne-la-Vallee site. But the western edge of the project is just six miles from Paris, so 100,000 people are already living within the perimeter in old hilltop villages and new subdivisions that make up 33 existing communities.

Because the flatter areas in which further development can take place most economically are broken up by ridges, Marne-la-Vallee is being planned as a series of population centers divided by green buffer zones along the ridges, like links on a bracelet stretched eastward from Paris. Connecting it all together is to be a high-speed regional subway extension of the Paris metro system. It would stop in every section of Marne-la-Vallee and become the project’s spine. Around each subway stop would be a center of stores, offices and community services for that section, which would then be encircled by rings of high-rise housing, lower density apartments and townhouses and, finally, single-family homes on the outskirts, bordering the surrounding green spaces.

The new town would resemble, more than anything else, the strings of suburban centers that dot the subway lines out of Stockholm. They, too, are separated by green buffer zones and flanked by large parks and open spaces. The difference that planners want to achieve at Marne-la-Vallee, however, is the creation of a complete city, not merely a string of suburbs with subway station shopping centers. So Marne-la-Vallee is also to have a larger city center with much more commerce, more places of employment, regional recreational and cultural facilities, a university, hotels, and high-density housing for several thousand people around a car-free mall and central park. The center is to be put on the extreme western end of the site because of the great need for its facilities by the existing factory suburbs there, as well as the eastern neighborhoods of Paris itself. It will be left mostly to the subway to make it seem an integral part of all of Marne-la-Vallee.

The planners also hope to tie the city together with two kinds of unorthodox circulation systems, however. One, which actually is rather common in “new town” projects, is a network of footpaths in each section’s green corridors. They would reach out from parks to be located near each section’s center through residential areas to the parks and open spaces around them. The other system would be composed of modified sunken roadways running out from the section centers through the most densely built up areas past all the places most people would need to go each day – housing, stores, offices, the university, schools, library, recreation areas. Each of these corridors would be divided by lines of trees into separate lanes for motor traffic, bicycles and pedestrians. The walks of the footpath system would cross over these corridors on pedestrian bridges and feed into their pedestrian lanes via stairways.

Right now, all the plans for Marne-la-Vallee are no more than pages in planbooks and colorful maps and drawings on the walls of rooms in a quaint chateau that has been converted into offices for the project’s etablissement public. Whether they can be translated into reality remains to be tested. As might be expected, neither of the two new towns planned for east of Paris, Marne-la-Vallee or Melun-Senart, is nearly so far advanced as the three to the west.

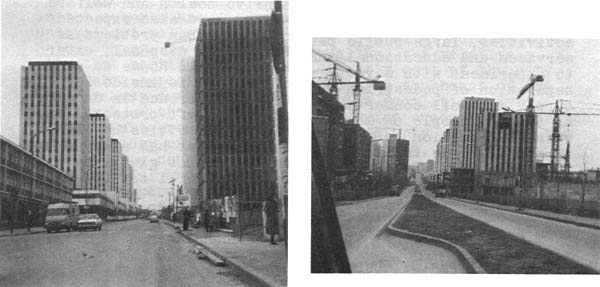

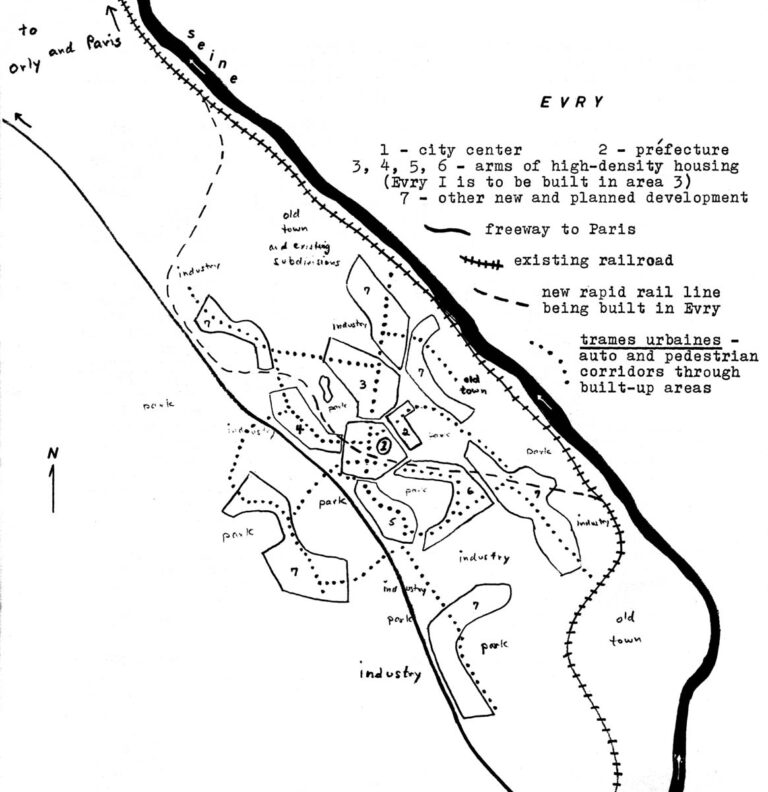

Evry, for instance, although located just across the Seine from Melun-Senart, is already years ahead in development. The principal reason for this is that Evry had to be started sooner and brought along faster in order to catch up with the already rapid suburban development occuring within its assigned area. Nearly 155,000 people were living there when work started on Evry in 1968, and its population has grown to more than 200,000 since, compared to just 60,000 in an area twice as large within the study perimeter for Melun-Senart. As industry pushed south along the west bank of the Seine from Paris to Orly airport, suburban subdivisions began to fill the flat farmland still further south where Evry is now. Although the site is 19 miles away from Paris, it is entirely possible that Evry’s target population of 400,000 by 1990 might have been reached without any planning or government intervention at all.

Industry had lagged behind around Orly, however, and many residents of the Evry area suffered difficult commutes to work. The rail line ran through the small old towns along the river, on the eastern edge of the Evry area and far from its new concentrations of population, and the freeway north fed into a monumental traffic bottleneck extending from Orly right into Paris. The lack of industry also meant less tax money for the existing localities to use to provide community services to the area’s many new residents.

Evry’s etablissement public has met this problem by attracting many new places of employment to Evry with the lures of tax breaks the project can offer, the flat building sites and the new roads, underground utility, water and sewage lines that were installed in advance. Two large commercial bakers, a paper company, an electronics firm, a regional telephone exchange and the prefecture(administration) offices for the local departement in which Evry is located are among the bigger installations. They all occupy attractive buildings scattered throughout Evry relatively near present and future commercial centers and housing, rather than being isolated in a large “industrial park” on some distant edge of the project. The prefecture, which alone employs several hundred people, is dominated by a long, raised building shaped like a giant slide rule that has become a landmark for the center of Evry.

Nature conservation and recreation areas were other important needs in Evry. Rapid development had threatened the fragile balance of soil and water in the former farming region and flood plain. Soil erosion and drainage problems could have become acute. To prevent this, Evry’s public corporation is completing a new $8 million water control and treatment system, including nearly ten miles of drainage canals and 25 acres of reservoir basins. Not only will this network help stabilize the area’s water table, it will also be used for outdoor recreation. In order to break the monotony of the flat land, hills are being created with the dirt dug out for the reservoirs. The new landscape is being planted with trees, grass and shrubs to create parks, since there are no natural woodlands in much of Evry,

Another important recreational resource will be the “Agora,” an unusual collection of buildings to be erected right in the middle of Evry’s city center. The Agora is to contain a 1500-seat sports arena, 600-seat theater, swimming pool, ice skating rink, bowling alley, library, other recreation and meeting areas, child care centers and social service offices. Pedestrian malls and ramps would link the various levels and buildings of the complex with each other and with the shopping and office center to be built around it. The intention is to create a 24-hour city center and end the separation of commercial, recreational, social and cultural facilities that has so far characterized French suburban development. Evry’s developers claim that it is “the first time in France” that such diverse public facilities are to be put together. In fact, the Agora appears to be a much larger and more comprehensive version of the Maison du Quartier social and recreational centers already being built in each quarter of the Le Mirail new town project in Toulouse in the south of France (See LD-7, Le Mirail: A Study in Concrete).

The keystone of Evry’s city center will be its new station on the main commuter railroad line, which is being diverted several miles west from its existing path along the Seine to pass right through the middle of the new town. The expensive process of laying the new track, tunneling much of it under Evry (which, of course, is easier in places not yet developed) and building the new station is already well underway; the station is to open in 1974. Paris metro officials are studying the possibility of running a regional extension of their system along the new rail line to Evry and across the Seine to Melun-Senart. Parking garages will be built both above and underground in the Evry center to hold the cars of both users of the center and commuters riding the train north to Orly and Paris.

Evry’s city center is being built alongside the prefecture complex in the middle of the largest tract of undeveloped ground left on the Evry site. Branching out from it are to be four arms of high density residential development, one of which is already under construction. The overall shape of this central area will be a giant “X,” with landscaped parks developed in the spaces between the arms. One of these parks already exists in the prefecture complex.

The nerve system of this central area and the collections of residential neighborhoods and industrial complexes beyond is to be a network of boulevards with separate rights of way for pedestrians and buses. These boulevards, called trames urbaines by Evry’s planners, would cut right through the middle of the most densely built up parts of the city in which commerce and public facilities would be located, much like the circulation corridors planned for Marne-la-Vallee. But public transportation would have highest priority on the trames urbaines of Evry and cars may even be banned from them completely and confined to roads around the edges of built-up areas and leading to parking garages within them. Offshoots of the trames urbaines inside each residential area may be limited to pedestrians only and take them past the local schools, maison du quartier, child care center and convenience stores. The first high-density residential neighborhoods are already being built for the Evry public corporation with separate pedestrian and auto networks, main pedestrian boulevards, foot bridges over the roads, and parking garages rather than open lots to free more of the site’s precious open space for recreational or scenic uses.

Thus, the general design theory for Evry calls for linear built-up areas with high densities, community services and a lively urban atmosphere along the central trames urbaines, with “backyard” green spaces flanking these configurations on each side. This kind of design, similar to that for the most recent linear new towns of Israel, (See LD-5, Israel’s Second Generation New Towns) attempts to provide residents with the atmosphere of both big city and suburban or rural life. Whether this physical plan can become social reality at Evry remains to be seen.

Planners and builders everywhere also are waiting for the results of a competition the Evry corporation has opened for the design and construction of “Evry I,” a residential quarter of 7,000 units to be located in the northeast arm of high density development in the center of the city. Necessary commerce and public facilities, roads, walkways and some means of public transportation all are to be included. Although Evry I must be economically feasible (the developer winning the competition would build it under turn-key contract for the Evry corporation, which would sell and rent out the buildings and facilities), entrants have been urged to find new ways to provide public transportation, minimize pollution and create a lively urban atmosphere within Evry’s overall suburban setting. Evry’s planners hope that the competition may produce techniques (possibly a new kind of local public transportation system, for instance) that can be used in the rest of the project. Evry I is to be partly subsidized by grants from the national ministries for culture and environmental protection to help pay for conservation of extra open space, development of environmental protection techniques and such visual amenities as unusual building design and outdoor sculpture. Winners of the competition are to be selected at the end of this summer.

At this early stage, at least, it appears that much of the development of both Evry and Marne-la-Vallee is to be heavily influenced by the physical design ideas and experiments of their planners, although little besides the competition for Evry I promises any startling breaks with what has been done elsewhere in the past. But at another new town project, Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, north of Evry and west of Paris, new ideas of planners are having little influence on the development underway in the project so far. There are two reasons for this: the philosophy of the project’s director and the limitations placed on the planners’ options by the location of the site, by an unusual relic of a past planning achievement and by inroads already made in the area by private developers and government highway builders.

The site for Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines is just southwest of the town of Versailles and the vast grounds of the royal palace built there by Louis XIV. Saint-Quentin is delimited by the town and several separate woodlands which are to be protected from further inroads by developers. The principal feature of the usuable area of the site is a huge reservoir, l’etang de Saint-Quentin, an engineering wonder completed 350 years ago at the direction of Louis XIV to store spring and rain water to be piped from this high spot through the intricate system of canals to the fountains and pools on the palace grounds. The system is still in use today and the original stones can be seen in the retaining walls of the reservoir, which is now the largest fresh water sailing basin in France. The site is also bissected by a railroad line and auto freeway (parts of which are still unfinished), which are to be its principal lines of communication with Paris. Although only about 60,000 people were living in the area in 1968, when planning began, several private developers, including Levitt and Sons from the United States, were already building or had government permission to develop new housing there. The population already has doubled and the new town’s planners have had to work within patterns established by these builders in some parts of the project.

As a result, Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines is to be a loose collection of rather scattered residential quarters, some of which were already under the control of private developers, with parks and industrial sites situated in the gaps among the housing estates. Each quarter is to have its own subcenter of convenience shops, schools, community services and such recreational facilities as swimming clubs. The city center is to be built on the north central edge of the project so that it can also serve the extensive existing suburban development outside Saint-Quentin (just as the center of Marne-la-Vallee is to do). It will be located on the railroad and freeway where they pass by the Saint-Quentin reservoir; a new railroad station in the center is to be built right over the tracks. The site’s high ground will give users and residents of the center a good view of the parkland around the reservoir and a smaller lake on the other side of the center. Pedestrian malls and walkways including bridges over the freeway are to connect all parts of the center with these two parks.

Except for the design of the city center, however, little planning is being done at Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines that is as experimental or deterministic as at Evry or Marne-la-Vallee. This is the result of a conscious decision by the project’s director, S. Goldberg, an engineer who does not believe that new towns, where hundreds of thousands of people will live, should be used as laboratories for planners’ experiments. He is more concerned with building good housing, developing roads and rail transportation, and attracting industry and commerce. These things are necessary, he told me, to satisfy future residents of Saint-Quentin and make the project work financially.

Thus, much of the housing built at Saint-Quentin up to now consists of familiarly designed rowhouses (740 of which are being put up by Levitt) and walkup and elevator apartments around lawns, play areas, swimming pools, schools and convenience stores, with parking on streets and cul-de-sacs close to each driver’s doorway. Goldberg does not see much difference between the trames urbaines and ordinary roads with sidewalks, and he does not expect the competition for Evry I to turn up much of wide applicability. In planning the city center, Goldberg is placing emphasis on the stores that can be attracted there rather than on plans for fancy complexes like Evry’s Agora. Although he said that there is to be plenty of recreational and cultural facilities, in Saint-Quentin, Goldberg added that “commerce is what draws the people; culture won’t do it.”

At the moment, automobiles are the only mode of transportation within Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, (as they are in Evry, although there are plans for the future). “I guess we’re a little behind on public transportation,” Goldberg said. He fears that a local transportation system is bound to cost much more than it will ever produce in revenue and he is not certain that Saint-Quentin’s taxpayers, present and future, will be ready to subsidize it. He said he would be interested in a bus system, even one that runs on its own separate road or track, but he simply is not certain that any will be feasible for some time to come.

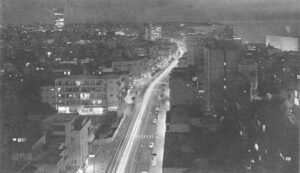

Meanwhile, Saint-Quentin is growing fast, and showing signs of strongly resembling the U.S. new town project of Columbia, Maryland – basically more suburban than city-like, not very experimental in land-use planning or housing design and, within the project itself, pretty much the domain of the automobile. There is one basic difference between Saint-Quentin and Columbia or any other U.S. suburb or new town, however, and that is its direct, high-speed rail link to the city. Residents of Saint-Quentin can reach the Montparnasse station near the middle of Paris in 24 minutes (and that time may be cut further in the future with the use of regional subway trains on the line to Saint-Quentin). It happens that a vast new office complex has been built around the Montparnasse station, where are now located the executive offices of several firms with plants on the cheaper, less heavily taxed ground in and around Saint-Quentin. The direct transportation link thus is helping business in the new town and making commuting particularly easy for Saint-Quentin residents who have been able to get jobs in the Montparnasse office complex; in fact, they need never set foot outside on a street in Paris while going to and from work.

Goldberg considers himself a pragmatist; he is trying only what he is reasonably certain will work and is shunning the untested. He believes that this is all that can be done with the time, money and resources at his disposal. And it is clear that Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines will be an improvement on what would have grown up there otherwise. Goldberg is improving transportation to Paris, conserving recreation and open areas, and balancing new housing with new jobs and commerce. The community’s promise has been sufficient to draw to it families able to afford the $40,000 single-family homes that make up one subdivision in a pleasant wooded setting, as well as those with more moderate incomes who quickly bought up the Levitt townhouses. Considerable question remains, however, about whether Saint-Quentin will really become a “new city” of distinctive urban character, as Delouvrier had envisioned. More likely, it may never be more than a collection of especially well-appointed suburbs, as may Evry or Marne-la-Vallee, too, despite apparently more ambitious plans for them.

An important question facing the planners and developers of the Paris new towns is whether physical design and facilities can, by themselves, produce a city. Attractive cities that have grown up more or less naturally (although most show the influence of some “planning” at one time or another, like Haussmann’s Paris) often benefit from fortunate physical locations or the charm of well-preserved older neighborhoods.

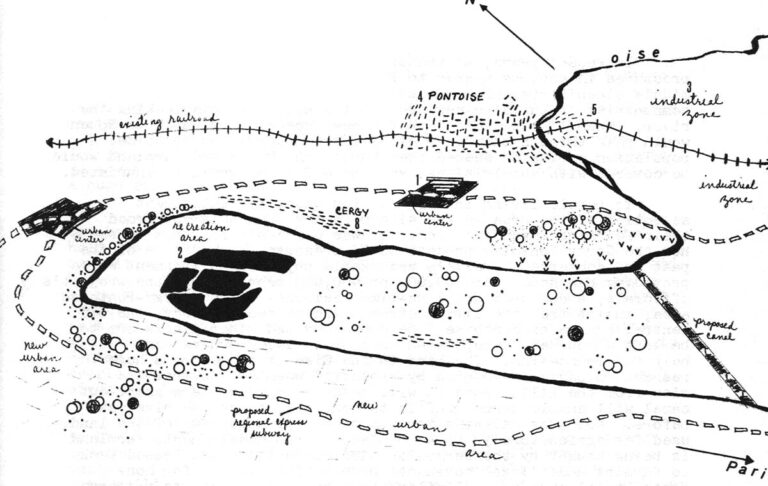

The fifth new town to be built outside Paris, Cergy-Pontoise, is blessed with just such an advantageous location and the unusually attractive atmosphere of the two old towns from which the new city takes its name, Cergy and Pontoise. The site, on a big loop of the Oise River, is not unlike that of Paris itself, except that the ground north of the river bend, from which the view is particularly impressive, is much steeper. The town of Pontoise was built long ago on flatter land east of the loop as a bastion for the defense of Paris against Normandy, and has been steadily prosperous ever since, located as it is on highway and rail routes northwest from Paris. In addition, barges on the Oise carry materials to and from factories situated between railroad tracks and river. Cergy is a much smaller little town on a hillside on the big river bend to the west. In both towns, there are picturesque streets and fine old buildings; attractive farms and the remains of a medieval monastery are nearby.

In recent years, as transportation improved and the population pressures in suburbs nearer to Paris increased, a growing number of middle class Parisians began buying big old houses in the two communities or building new ones on the hillsides overlooking the river. When it was decided that a new freeway from Paris to Rouen would pass through the Oise valley between Cergy and Pontoise, a population explosion seemed inevitable; the hills and farmland would be covered with subdivisions, and the old towns would be inundated.

To people living in Cergy or Pontoise, the subsequent selection of the area as the site of a new town only confirmed their fears of impending doom. It was difficult for them to see how the Cergy-Pontoise project could preserve the heritage of the past and conserve the site’s remarkable physical environment while providing new homes for 300,000 or 400,000 people. But the project’s officials, among whom are long-time residents of the Cergy-Pontoise area, insist that the little streets and houses of Cergy, the old central square of Pontoise, the monastery and other places are to be left untouched, except when home or building owners want help for remodeling. The bend in the Oise is to become a huge recreation basin surrounded by protected woodland so that the view from the hills above it will never change, while a short-cut canal will enable barge traffic to continue to use the river as before. Not just existing forests there but also some of the land used for agriculture is to be protected from development; farmland is being bought by the Cergy-Pontoise corporation and leased back to farmers under legal covenants prohibiting its use for non-agricultural purposes. (Similar steps have been taken to preserve old villages, landmark buildings and open spaces in the other new town projects, too.)

The new development planned for Cergy-Pontoise also is to be pragmatic – “nothing foolish” – according to Jean Lachenaud, the secretary-general of its etablissement public. Nothing, except perhaps the inverted-pyramid building for the prefecture of the departement in which Cergy-Pontoise is located, will be very radical in design. Yet certain planning principles are being strictly followed which will make the higher density areas of the project somewhat more urban than Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, while more of the rural nature of the site around them is being preserved.

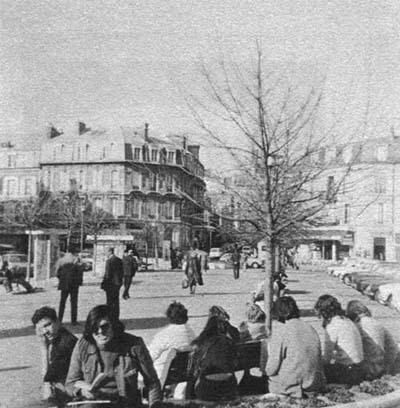

The newly developed areas of Cergy-Pontoise are to be highly concentrated to permit pedestrian access to as much as possible and the integration of almost all public facilities with housing. Separate pedestrian and auto circulation systems will be maintained throughout the project; well-designed pedestrian bridges already have been built across roads everywhere that new construction is taking place. The new town’s conventional public bus system (a compromise between hopes at Evry for some new kind of bus transportation and the lack of any at all so far at Saint-Quentin) already connects the old town square and railroad station in Pontoise with the prefecture and new housing and shopping areas in the new center of the new town. The project’s first commercial and high density residential center is being built several yards away from the prefecture building (other public facilities are to be built in between), and residents will eventually be able to go from one to the other in a variety of ways: driving, riding the bus or walking across a huge pedestrian mall that will connect the two.

The center around the prefecture is actually the first of two to be built at Cergy-Pontoise. It is to be big enough to hold every desirable public facility, including a town hall, exposition hall, theater and stadium, in addition to commerce and housing. Yet it is small enough in scale to be developed right along with the initial stages of housing nearby. When the first tenants moved in to the new apartments near the commercial center this spring, for instance, a large grocery and department store was already open and waiting for them. A second much larger city center will be built later on a plateau on top of the hills overlooking the river. Both centers will then be joined to each other and Paris by a new regional metro subway line.

Such a regional subway already extends westward from Paris to La Defense, a new office center being built in an old suburb between Paris and Cergy-Pontoise. La Defense will eventually employ 100,000 people and house 25,000 in metallic modern high-rise buildings on 1,700 acres of land where little old brownstones had been previously. At one time, before the five present new town projects around Paris were begun, La Defense, for which planning began in the 1950s, was being called a new town. It is instead a suburban “urban renewal” project on cleared land which will be mainly an office complex, not a balanced community. The apartment units there are high priced and intended to be prestigious and convenient suburban homes for executives and professionals, similar to the residential areas of EUR south of Rome.

La Defense has, however, become a testing ground for basic techniques to be used in the five Paris new towns. Its partially completed center is a mile-long raised pedestrian mall that covers successive layers containing the subway station, a bus station, a parking garage for 20,000 cars, a shopping center and a twelve-lane freeway. It is being used as a prototype for the design of the city centers for the new towns, although none will be exactly like La Defense, nor will they be ringed by a comparable Manhattan-like forest of skyscrapers. The new subway connects the La Defense station with another under the Arc de Triomphe in western Paris in just over three minutes, and then speeds non-stop to a station just opened in the central Paris business district near the Opera. The line eventually will be extended in the other direction from La Defense through the western suburbs and ultimately to Cergy-Pontoise.

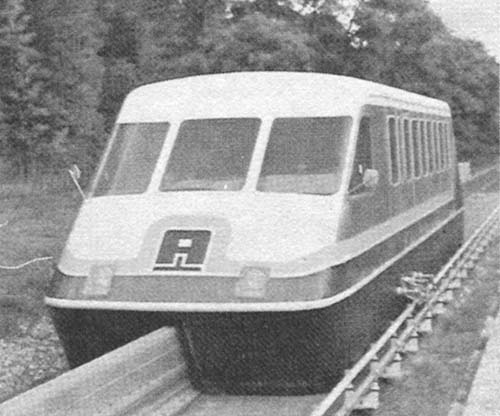

In the meantime, however, if plans approved by the national government late last year are realized, the two centers of Cergy-Pontoise will be linked directly to the office complex at La Defense by an even faster, 180-mile-per-hour non-stop turbo train. Powered by a jet engine, it would run on a cushion of air on a single-rail track. This would give to Cergy-Pontoise the same kind of link with an in-town headquarters office area that Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines has with Montparnasse, except that La Defense is much larger and houses the executive suites of many more financially powerful companies, including Esso, IBM, Fiat, the French Line and several of France’s largest banks. The developers at Cergy-Pontoise hope that middle class workers in those offices will move to the privately built homes scheduled for Cergy-Pontoise after the subsidized housing being built now has attracted the first wave of new residents to the project.

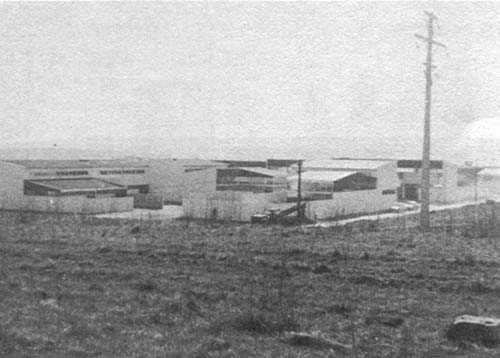

Arrangements already are being made to locate plants in Cergy-Pontoise for several firms with executive offices in La Defense; among the first to agree were Fiat and Johnson of France. In La Defense, each business locating so close to Paris must pay a 250 franc (more than $50) penalty tax annually for each square meter occupied. However, this tax, part of a national effort to discourage continued business concentration in Paris, has been reduced to only 25 francs (a little more than $5) per square meter for office or plant space in Cergy-Pontoise. It is characteristic of the Cergy-Pontoise project that, in addition to the big plants and offices, there is also an attractive group of small modern workshops, already built and being expanded, in which 32 individual craftsmen – from window glaziers to furniture makers to house painters – can live, work and maintain small sales rooms at a cost of $34,000 for each fully equipped combination unit. The big plants and offices, however, are the ones that the Cergy-Pontoise corporation boasts in its advertising; they will be helping to pay for the turbotrain, the buses, the pedestrian circulation system and the public facilities of the centers.

Money is a problem for the new town projects. The loans made to them by the French government are, like all French financing, short term; they become payable in six years (although the government will, when necessary, loan more money to pay the interest and principal on previous debts until a project’s momentum is built up.) The national government also has become increasingly insistent recently that each new town pay for itself, more than was originally envisioned. The government loans are to be repaid and public facilities financed almost entirely out of land sales to developers, income from each public corporation’s own construction and local taxes.

“The people in Paris keep saying that the American develepers pay for everything out of land sales, so why can’t we,” a high level planning consultant for the Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines project told me. “They forget that American developments and shopping centers are too commercial for this reason. We are trying to build a railroad station, theaters, libraries and other things for recreation and culture – not just stores. But the government tells us to finance it all from land sales.”

Because the public corporation must also give private builders a share of the profits, the planner adds, it has still less money to put into public facilities. He would like to see the French new town corporations build all housing, stores, offices and factories and then sell or rent the finished buildings, collecting and reinvesting all profits itself. This is what has been done by new town corporations in England, where most projects ultimately gain a surplus to be used for continuing public improvements.

Another peculiarly French problem cited by the Saint-Quentin consultant is the fact that the projects around Paris are directed mostly by engineers and accountants, with architects working for them. Engineers get the top jobs, he explained, because they are the planners of most other government projects in France – roads, airports, public buildings – and have worked their way into the chairs of the national ministries from which the new town building effort is being directed. The accountants are there to follow the spending of each penny of government grants and loan funds, as is the French bureaucratic custom, and these men often have a decisive say on big decisions made in the new towns. The architects, who are the “urbanists” in France, are little more than soldiers in this army. Hence, the emphasis in the Paris new towns is on such basic engineering projects as new highways, subways and masses of big new buildings.

As a result, there is little idea or interest within the decision-making circles of new town corporations of the effect their plans will have on how people will live in the projects. Housing, perhaps the most important factor for future residents, has been left almost entirely up to developers, both profit-oriented entrepreneurs and the bureaucratic public-private builders of subsidized housing. When officials of each project were asked if social scientists had been consulted about the likely human reactions to what appeared in the master plans, the question was thought irrelevant. There is no precedent for this in France. Engineers and social scientists do not attend the same universities, much less come across each other in their professional lives.

Because of the bureaucratic caution best expressed by Goldberg at Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, himself a government engineer, the Paris new towns also are not having much to do with experimentation with new answers to urban problems. Not bothering does make it easier for the developers (and perhaps even for residents if some experiments were to fail), but without experiments in air pollution control or internal public transportation, for instance, how will the Saint-Quentin area remain a haven of fresh air to which people can escape from the smog closer to Paris? Levitt’s townhouses and the American-style detached houses are popular with homebuyers, but is there not a way to provide what those families are looking for in a home while also making more efficient use of the land? Without experiments, research or even any interest in these questions, answers will never come.

Nevertheless, there are many notable advances being made in the development of the new towns of Paris. Each project is being linked by high-speed commuter rail lines with central Paris, even where it means laying new track, building new stations or developing a new vehicle like the turbotrain; the Paris projects have not been limited to locations on already established lines of transportation. The necessary transportation is being built to each of them instead. Preferential tax treatment has been given the new towns to attract industry to them, so that jobs can be provided near new homes and industrial pollution can be minimized by careful good planning in a new town context. Much more direct government financial help is being provided than would be the case in the United States (where a few private “new town” projects are presently aided by government guarantees of private financing at high market interest rates), even though some thoughtful French planners complain that it is not nearly enough. More public facilities are being provided in the Paris new towns, although some financial problems have delayed such ambitious projects as Evry’s Agora. A large amount of subsidized housing for both moderate and lower income families is being built, although one reason for this is the fear of officials that this may be the only kind of housing that would attract the first families to even such conservatively planned experimental communities. In Cergy-Pontoise, at least, the subsidized housing also is being mixed with privately built homes, a definite departure from the usual French (and U.S.) practice of strict stratification of new suburban housing.

Finally, it must be noted that although it may already be in need of some revision and liberalizing, there now is a national new town policy in France, a policy aimed at replacing chaotic suburbs with better urban developments produced through the cooperation of government and private business. It will now be interesting to see, as the new towns of Paris grow, whether they will really become better places to live than the still rapidly multiplying traditional suburbs around them.

Received in New York on July 7, 1972.

©1972 Leonard Downie, Jr.

Leonard Downie, Jr. is an Alicia Patterson Fund Fellow on leave from The Washington Post. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Downie, the Post and the Alicia Patterson Fund.