Stockholm, Sweden

June, 1972

United States city planners, disheartened by the physical and functional disorder of the uncontrolled spread of urban America, have always been very enthusiastic about what they find when they visit Sweden. Very little of the growth of the vast metropolitan area of Stockholm, by far Sweden’s largest city, has “just happened.” The purposefulness of its planning can be seen from the window of any one of Stockholm’s green subway trains as it emerges from its inner-city tunnels and travels above ground through the “suburbs” in any direction.

The residential sprawl and chaotic neon commercial shopping strips of American cities are nowhere to be found. Instead, around every subway stop are orderly clusters of stores and public facilities that are, in turn, ringed by high density housing, row-houses and some single family homes, and, furthest out, great open spaces, usually woods of tall pines and massive gray rock surrounding grassy meadows leading to the shore of one of the region’s countless lakes and inlets from the sea. Between subway stops in many places the parkland closes right in around the track before opening up again for an area of concentrated development at the next stop. The rider seams to be traveling from town to town in the countryside rather than remaining within Stockholm’s city boundaries in areas already fully developed within the limits set by government planners.

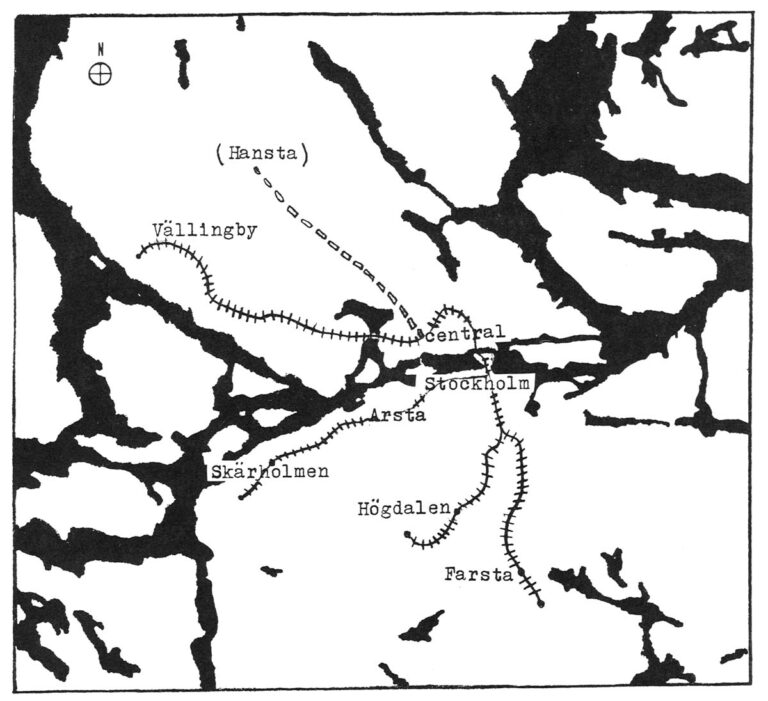

A look at the city map confirms the conclusion that Stockholm, outside its relatively small dense core, is a vast green park with fingers of development running through it along the subway lines and a few highway corridors radiating out from the center. It is possible to begin in the middle of Stockholm and hike miles in any one of several directions to the city limits and beyond without ever leaving parkland. A resident of any suburban population center is never more than five or ten minutes’ walk from almost wild woodlands and open spaces. Americans may not want or need quite that much contact with nature, but because the Swedes do they planned carefully to provide it.

Stockholm’s suburbs in the countryside also are very urban places, however. For all their love of the outdoors and the largely introspective, private lives that they prefer to live inside their homes or in solitary communion with nature, Swedes also have come to depend on the resources of cities, where the many well-known advances and comforts of modern Swedish design are conceived, produced and consumed. The Swedes are sophisticated consumers, and they expect a wide range of commercial facilities to be just as accessible as open parkland, ideally within walking distance of everyone’s front door. The health, welfare, child care and other public social facilities that the Swedes pay for so dearly with their taxes must also be located conveniently nearby.

As a result, built around each stop on the suburban extensions of the subway lines is a modern town center for the 5,000 to 20,000 people living within walking distance of it. These centers are not the shopping strips of carry-outs that the American suburbanite must depend on for daily needs; rather they look and function like town or village centers, with a variety of commercial and social services and a distinctive architectural unity that marks them unmistakably as the focal points of the population concentrations around them. One usually steps out of the subway station onto some kind of pedestrian mall that also can be reached on footpaths from much of the neighborhood around it without frequent crossings of streets. Even in older suburban areas somewhat removed from the subway lines, there are similar centers with pedestrian areas as well as parking spaces that have been integrated into the community around them rather than being left physically isolated and accessible only by car, as are suburban shopping centers in the United States. Higher density housing, including apartment towers, are built into or immediately adjacent to these Swedish centers.

Near the far end of each subway extension, distant enough from downtown Stockholm that another “downtown” is needed by suburban residents and yet near enough (30 minutes or less by subway) that it need not attempt to provide everything that one can find to do in central Stockholm, are much larger centers comparable in size to the largest U.S. shopping centers. Each of these is also built around a subway stop, although each dwarfs the little centers that flank them up and down the line. The large centers also are integrated with housing and community services in coherent communities of as many as 30,000 people each, although the commercial and social center itself is expected to serve as “downtown” for the 100,000 to 200,000 people who can reach it easily from other nearby suburban communities on the subway line and auto freeways.

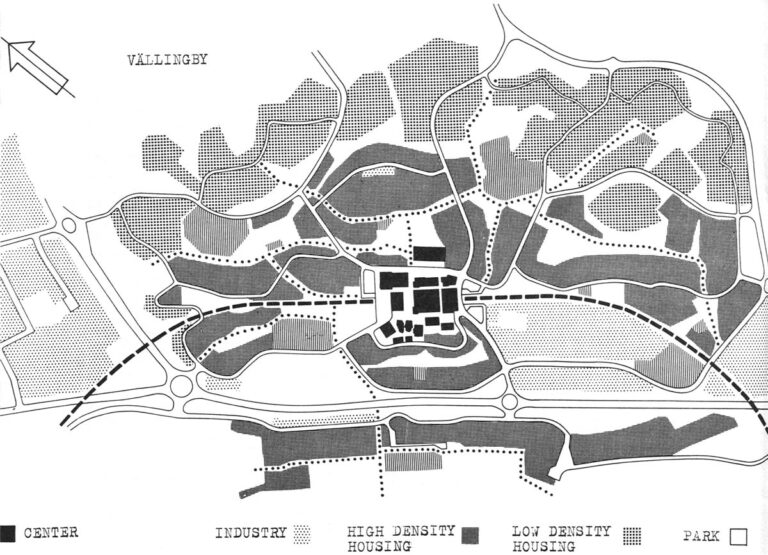

These large “regional” suburban centers are the projects that are best known in the United States as the “new towns” of Sweden: Farsta and Högdalen towards the end of two separate subway lines south of Stockholm; Skärholmen on another line to the southwest; Vällingby on still another line to the west; and Hansta to be built next on a subway line under construction to the northwest. These centers are much more than what Americans know as shopping centers, although they and the best new American centers (which sometimes have been patterned after them) do share some physical traits. The Swedish centers are complete communities of housing, commerce, factories, offices, recreation and public facilities intermingled in high density cores, around which have been developed rings of lower density housing and parkland.

But they are not entirely self-sufficient new towns. As already mentioned, they serve as “downtown” centers for several surrounding suburban areas developed in concert with them, and they are integral parts of Stockholm itself. Although it is quite possible to live a full life within the relatively small physical area (about one square mile) of Vällingby center, for instance, as some people do, it is also easy to ride public transportation to almost anywhere else in Stockholm, or, conversely, to reach Vällingby from anywhere else. People commute both to Vällingby and away from it. It is a city in itself and part of a much larger city at the same time. Although downtown Stockholm is quite healthy economically and continuing its own pioneering redevelopment, the city as a whole has become poly-centered, relieving population pressure on the inner city and bringing the advantages of urban living to residents situated quite far from it, both those who have moved out to be even nearer to the protected countryside and those attracted by the lower prices of more distant suburban housing.

Swedish law and the city’s own foresight have given Stockholm enviable power to strictly control the development of its new suburbs. Since 1947, private landowners have been prohibited from making their own subdivisions for the building of new developments. Instead, local governments have the exclusive authority to decide what may be built where within their metropolitan areas. Under another new law, nearly all of Sweden is included within one municipality or another. A 1965 nature conservation law also prohibits even rural residential use of land officially designated as valuable for recreation or scenic beauty. Thus, Stockholm has been able to locate suburbs where it wanted them and then set aside large areas of protected open space around the suburbs.

In addition to this legal authority, the city of Stockholm also enjoys the power of ownership of 80 percent of the vast suburban land within its municipal limits outside the small old city core. Stockholm began buying land in 1904 and owns more than 125,000 acres today. Farsta was built on an old farm acquired by Stockholm a half century ago, and Hansta will be built on a former military base bought by the city just recently. Thus, Stockholm both can control what will be built on the land within its far-reaching municipal boundaries, and can prevent, through its own ownership of the land, real estate speculation and the inflation of land prices.

When city officials decide it is time to develop a new suburban area (sometimes at the request of a prospective developer), the project is planned in detail under city supervision. The particular use of every square foot of land and floor space, the location and size of every building, the provision for every road, footpath, recreation area and park, and the design and content of the commercial and social center all are decided in advance with official approval. Occasionally, design competitions are held for particular developments or parts of them.

Developers then rent the land from the city on relatively low-cost, long-term leases and are free to design each individual building as they please within overall specifications for location, size and function. Housing and places of commerce and business are both sold and leased by these developers, most of which are limited-profit or non-profit syndicates formed by labor unions, local governments, tenant groups and, in some cases, building material suppliers and conventional developers. The national government provides the financing for 90 percent of new residential development. Until recently, it had also directly subsidized much of it, usually with lower interest rates on the financing, to relieve what had been an acute housing shortage in Sweden. Because that effort has accomplished much of its purpose, and the Swedish population and economy have leveled off somewhat, these subsidies for developers are being phased out. Rent and mortgage subsidies for individual needy families will continue, however.

The pervasiveness of the planning of Sweden’s urban growth is often difficult for Americans to understand. “Planning” is respectable in Sweden, where private options of many kinds are curtailed to accommodate what is believed to be the public good. Probably the best known example is the country’s steeply progressive income tax (with an effective rate of 20 percent of a $6,000 income, 40 percent of $10,000, 50 percent of $20,000 and up to 85 percent in higher brackets) that redistributes much of the private wealth and pays for such public welfare programs as universal health and dental care, sick pay for incapacitated workers, including housewives, a minimum income for the unemployed and day care for children of working mothers. This leaves few people really wealthy, but there simply are no slums or desperately poor people in Sweden.

In striking contrast to the private beaches and lake and ocean front developments of the United States, all of Sweden’s many miles of seashores and lake shorelines have been kept undeveloped and open to the public. There are no private buildings on or barriers along them. Unlike the country’s tax and social welfare systems, this is one policy that cannot be attributed directly to the welfare state Social Democrat Party that has been in power in Sweden almost continuously since 1932. Rather it follows from a traditional Swedish common law principle of equity – “the right of common access” – which also gives any citizen the right to move freely over any land in the country, public or private, as long as he does not damage crops or property. This basic willingness of the Swedish people to limit individual rights of private property and enterprise for the common weal, especially when necessary to preserve public enjoyment of nature, is an important factor in its strict city planning laws.

Sweden’s first planning legislation was promulgated in 1867, at a time when its planners were mistakenly trying to impose on Stockholm’s islands, hills and open spaces the rigid grid street layouts so fashionable in Europe. Fortunately, Stockholm’s population was still only about 100,000 then, since industrialization and the growth of cities proceeded much more slowly in Scandinavia than on the continent, and Stockholm’s 18th and 19th century inner city of stone buildings did not become a stifling, teeming slum. Instead, it remained relatively open to the great green spaces preserved in and around it by Sweden’s kings.

By the time Sweden’s modern era of rapid economic growth and urbanization began in the 1920’s, new city planning ideas were being carried from country to country in Europe. Inspired by the first “garden cities” of England and the experimental suburbs of Germany, planners were abandoning the old tight grids of tenement-like buildings for low density developments arranged irregularly on the land with large public open spaces. The primary objective of this planning – to restore to city dwellers access to fresh air, light and greenery – was particularly attractive to the nature-loving Swedes. So it is not surprising that when the turbulence and war of the 1930s and 1940s brought this kind of experimentation to a standstill elsewhere in Europe, Sweden became the leader of the western world in innovative urban planning.

Swedish planners were among the first to discover and adjust to shortcomings in the garden city model, with its dependence on the small self-sufficient neighborhood built around a school and a few stores and the arrangement of housing around large, grassy neighborhood open spaces patterned after the village greens of England. In Sweden’s cold winters, these open spaces, too small to be the wild woodlands preferred by Swedes, became barren, wind-swept places of little use. The neighborhood unit proved to be too small to support the commercial and social services the Swedes expected from urban living. They wanted much more within walking distance of their homes.

So they built higher density suburban communities with commercial and social center cores and outer rings of unspoiled parklands – truly urban living in a countryside setting. Housing was integrated with commerce and community services, and later with industry and offices, to imitate the variety and animation of city life. The Swedes also insisted on much more in the way of social resources for these new suburban communities.

The best example of this pioneering suburban planning is the Arsta neighborhood and center developed relatively near central Stockholm in 1947, before it could take advantage of the subway system then under construction. The center was built into a protective and attractive rocky hillside as an L-shaped collection of buildings around a pedestrian square. It contains stores, offices, apartments, medical services, welfare offices, clubrooms, chapel, restaurant, cinemas music auditorium, indoor theater and an outdoor amphitheater hollowed out of the hillside. Much of the site is wooded. In comparison with the first commercial centers begun in English new towns at about the same time, Arsta is notable for the amount of space given to public and social functions and for its human scale and attractive setting.

Development of bigger centers in larger residential areas then began to follow the various subway lines out of Stockholm. Vallingby, the first of the large “regional” centers, is by far the most innovative for its time and remains today the most remarkable and attractive example of Stockholm’s high density suburbs.

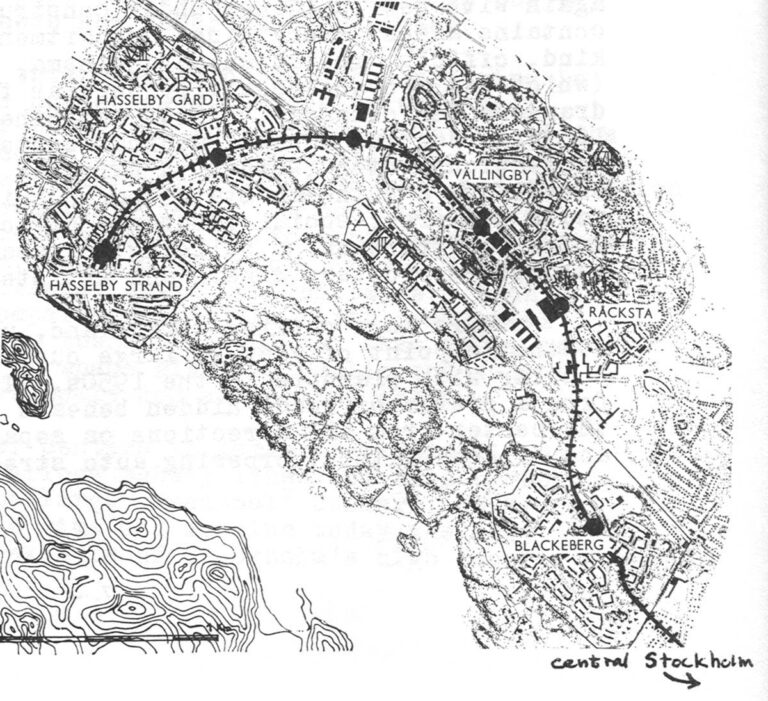

Begun in the 1950s, the Vällingby area is a linear “new town” of suburbs built around five stops at the end of the subway line west from central Stockholm on a ridge along the northern shore of a finger of Lake Malaren. The subway out from the city stops first at Blackeberg, an area of single-family houses and narrow three-story walk-up buildings, called lamellas in Sweden. Then, after passing through a buffer zone of the tall trees and massive gray rocks that fill the vast parkland outside the built-up areas, the train reaches Racksta, a collection of massive gray office and apartment towers facing, across the subway tracks, a factory area on lower land – all in all the least impressive of the Vällingby group. Next is Vällingby itself, a huge shopping, social and office center on a spacious concrete deck over the subway tracks in a valley flanked by ridges covered with apartment towers and lamellas. In the next wooded buffer area that the subway enters, there is an extra stop for another cluster of factories built in amongst the trees. Then comes Hasselby Gard, a pleasant collection of big and little apartment buildings on hilly wooded terrain. Finally, the subway reaches the last stop on the line, Hasselby Strand, a cluster of especially attractive lamellas winding through the trees down a hillside to the shore of the lake. The whole Vällingby community forms a large backward “C” from Blackeberg to Hasselby Strand, with the vast open area in the C left as a park of grassy open space and heavily wooded steep hills separating Vallingby’s center from the lake.

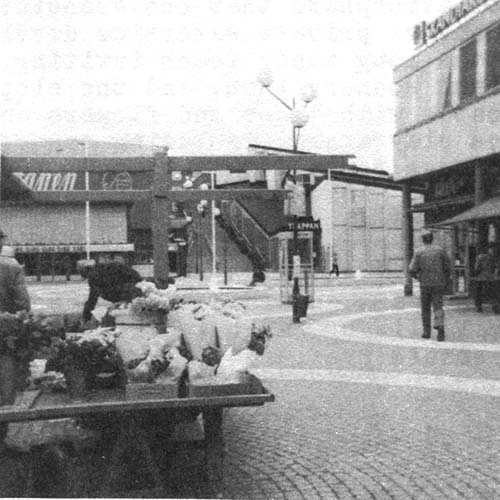

As interesting as the subway ride is, the best way to see Vällingby is on foot. Above the Vällingby center subway station is a spacious pedestrian mall covered with colored concrete blocks forming large circles that are filled here and there with decorative pools and fountains. The huge commercial and social center, which was doubled in size in the mid-1960s and is now being enlarged once again with new buildings under construction over the subway tracks, contains almost everything: department stores, shops of every kind, offices, restaurants, a cinema, a community meeting hall (which has proved especially popular for community meetings, dramatic performances, dances and other kinds of entertainment), library, dancing school, medical center, police station, youth recreation center (without a swimming pool), an interdenominational chapel and a Lutheran State Church building (both with their own youth centers), social insurance office, bus terminal, and now under construction, a building for small craftsmen, including carpenters, pottery makers and artists.

There is a parking garage and, unfortunately from an aesthetic point of view, a large outdoor parking lot of the kind popular with planners in the 1950s. Trucks service the center from a system of roads hidden beneath it. Pedestrians can reach the center from all directions on separate footpaths, underpasses and bridges without crossing auto streets.

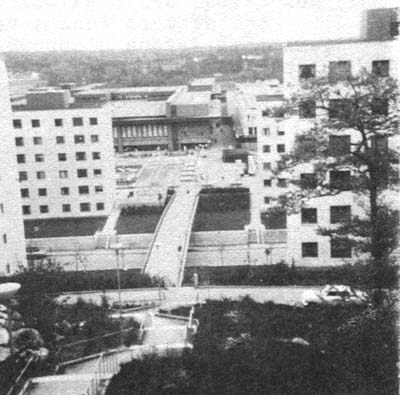

VŠllingby Center: The aerial view (top) makes the center appear much more monolithic than it actually is, does not do justice to the preservation of nature around the center and the well-done walks and underpasses that take pedestrians from residences to the center without contact with the large parking lot, the service roads or the subway track (which runs from top to bottom of the picture) under the middle of the center.

Housing is available in apartment towers right in the center and in lamellas on the hillsides on its fringe. Walkways and steps lead down to and through small parks and playfields up to other wooded hillsides to more lamellas, some attractively designed to blend in with the trees. They all face onto pedestrian paths with cul-de-sacs and roads for car traffic and parking behind them. Some of the other walkup apartment blocks, built early with subsidies for low-income families are obviously inferior in design and construction compared to the rest, yet they, too, benefit from their location on the edge of the parkland that surrounds all of Vällingby and its suburban neighbors. Schools and day care centers for children of working mothers are interspersed with the housing. There is no need for groups of neighborhood convenience stores because no resident is more than a third of a mile walking distance from Vallingby’s center. Residents of the surrounding suburbs on the subway line are situated just as close to the smaller commercial and social centers built around the subway stops of Blackeberg, Racksta, Hasselby Gard and Hasselby Strand.

Less than four or five city blocks’ walk southwest from the middle of the bustling Vällingby center is the huge 500-acre Grimsta park in the middle of the C-shaped project. Much of It was originally set aside for housing, but the planners decided to increase residential densities elsewhere in Vällingby to save more of this scenic area for park. It can be used as a pleasant shortcut when walking from one of the other suburbs to the Vällingby center, for outdoor games on its spacious grassy meadows or in any of several equipped recreation areas, for long strolls or bike rides along its network of paths (which are lighted at night), or for more ambitious hikes through its heavily wooded hillsides to the beach on the park’s far side along the shore of Lake Malaren. Adjacent to the beach, on the shore below Hasselby Strand, there is also a pleasure boat marina.

Vällingby is a community of working class and middle class families. Yet the view from the marina, either out across the lake, past several islands to the far shore, or, in the other direction, up the wooded slopes toward the housing of Hasselby Strand, is full of the kind of atmosphere that one associates in the United States with expensive private waterside developments. The water is clean and blue, the long sandy beach inviting, the marina picturesque, the woodland scenery lush, and the slopes up to the housing well landscaped with trees and flowers and dotted with large, imaginative play areas, including one of several wooden playhouses and huge rocks for climbing. Retaining and dividing walls are made out of attractive stone, and the footpaths are nicely landscaped and fitted out with benches and lights. Although the density of housing is fairly high to free more space for public uses and parkland, it does not seem crowded in the many areas where buildings are separated from each other by trees and rocks. Clearly, Vällingby has been built for people rather than for maximum real estate profits.

Vällingby’s trees and rocks…

waterside views…

well-landscaped housing…

generous open space…

well-equipped parks…

and attractive, useful pedestrian ways.

The Vällingby area contains housing for about 60,000 people and employment for 9,000 in both non-polluting factories of firms like IBM and Phillips and in offices and stores of the centers. About 5,000 of those jobs are filled by residents of the Vällingby area itself and the rest by commuters from elsewhere. Besides the 5,000 who work near their homes, 13,000 Vällingby area residents commute to central Stockholm and 7,000 to other suburban areas.

The majority of the housing units in the Vällingby area are in the various kinds of three-story walkup buildings. Nearly 70 percent of the area’s residents live in them, while 20 percent live in elevator-equipped tower buildings (up to 18 stories) and 10 percent in single family homes. Multi-family housing is not unpopular in the Stockholm area, partly because so many families (50 to 60 percent, according to a recent survey) have small second-home vacation cottages elsewhere.

Among the weaknesses of the Vällingby project is the housing provided for the elderly in high-rise apartment buildings. Their older residents are lonely and isolated in the towers, cut off both from the human flow of the community and the attractions of nature more accessible to families in lower density housing.

The commercial center proved too successful, as far as planning for it was concerned, and it has created parking problems and traffic congestions on the roads approaching it. While the strong demand by businessmen and shoppers for further expansion of the center’s commercial facilities has been satisfied, few new public or social facilities have been added. Thus, the almost even balance between commerce and social facilities of the pioneering Arsta center has been lost in the financial prosperity of Vällingby center.

The popularity and prosperity of the Vällingby project as a whole also has narrowed the range of social groups among its residents. As demand for housing there has forced resale prices up sharply, more middle class families have replaced the working class families who originally moved into Vällingby with the help of housing subsidies. As a result, the Stockholm area as a whole was left with a continuing shortage of housing for lower income families.

Planning for the next two large suburban projects – Farsta and its surrounding suburban communities, begun in the early 1960s, and Skärholmen and its environs, still under development today – was strongly influenced by both the economic success of Vällingby center and by the still large demand for low-income housing that it left unfilled. In addition, the development of these two has been affected by the declining economic growth and governmental financial health of Sweden, with pressure put on planners to save kroner wherever they could and to make each project as economically self-sufficient as possible. Unfortunately, these circumstances have denied to its successors some of the experimental zeal and government largesse that went into Vallingby.

Farsta is a significantly less varied and physically attractive community than Vallingby. Its buildings are more monolithic, larger and more densely grouped; one-third of its residents live in tower buildings compared to one-fifth at Vallingby, although almost 20 percent of Farsta’s families live in single family homes. Farsta’s center is almost completely cut off from the community around it by sprawling surface parking lots. Its footpaths are not so numerous as in Vällingby nor nearly so nicely landscaped; the tunnels that take them under roads are smaller, much less well lighted and have plain concrete walls in place of the brightly patterned tiles of those in Vallingby. Although Farsta still provides good modern housing, several thousand jobs, plentiful community services and reasonably attractive surroundings (on another wooded site on the shore of Lake Malaren) for working class families who needed them, it has failed to improve on the promising start made at Vallingby.

Skärholmen is even more disconcerting. It has profited in some ways from lessons learned at Vällingby and Farsta; yet it is, in many other respects, a disappointing step backward. Financial constraints, including the high cost of construction labor, have deprived Skärholmen of still more of the human scale and generous amenities of Vallingby. And its developers were allowed by Stockholm planners to place an overly heavy emphasis on its commercial center, which they hope will pay for much of the rest of the project.

Thus, as a shopping center, Skärholmen is the most ambitious yet begun outside downtown Stockholm itself. It is intended to serve a suburban area that will eventually house 300,000 people. Its first parking garages hold 4,000 cars and have an automatic fee collection system supervised by television monitors. In one improvement over Farsta and Vallingby, both the garages and an extensive system of roads for trucks servicing the center’s shops have been hidden under the Skärholmen center’s concrete pedestrian deck in a cavity hollowed out of solid stone in some places and supported by pilings in soft mud in others.

Commercial enterprises are being allotted four times as much space in the Skärholmen center than are social and cultural activities, although a secondary school and recreation center with an indoor swimming pool are to be built in the center. Its large library, which will be shared by the general public with students of the secondary school now under construction, is already Skarholmen’s cultural focal point and has received high praise in resident surveys. However,Stockholm has decided it cannot afford to provide Skärholmen with a meeting hall, which has proved to be a very popular facility in Vallingby. And most of the rest of the social and cultural facilities, including a cinema, a church and the sports and swimming pool center, are not to be built until much later with public funds that have not yet been found, even though several thousand people already live in Skarholmen.

The center’s stores, which occupy twice as much floor space as those at Vällingby center, are already finished and open, however. The center’s design has been most strongly influenced by the big chain stores, which occupy key spots in rather unattractive big buildings, while much less attention has been given to public uses and spaces. The attractive stone mall, fountains, benches and landscaping of Vällingby are all missing in Skärholmen center. Significantly, many of Skarholmen’s stores are open at night and on Sundays and do a good business at those times because there is little else for residents to do.

Housing appears to be mostly an afterthought so far at Skarholmen, with its importance seemingly limited to providing customers for its many stores. On a steep hillside just above the center are tier after tier of rectangular eight-story apartment houses – massive boxy structures strung out monotonously like the discredited immigrant housing built in Israeli new towns in the 1950s and early 1960s. Although the difficult terrain and increasing cost of building for low income tenants made mass production of the housing necessary, something could have been done to make it more attractive.

The hill is so steep that, in addition to stairs, elevators have been installed in the side of it, and the shortcomings of Skarholmen’s planning and execution are well illustrated by the barrenness of the long dark corridor leading into the hillside toward the elevator. The corridor’s walls have been defaced and the elevators vandalized by children with little else to do. Children also have broken many of the shopping center’s light fixtures and frequently jammed the escalator connecting one level of the center with another.

Overall, there is much less in the way of both recreational facilities and wild open space at Skärholmen that there is in Vallingby, although very young children have been provided with small clever wood, concrete and sand play areas up against the housing on the hillside. Older children have little place near their homes but the tiny, badly trampled front lawns of the apartment buildings. Where there had been well equipped, spacious terraced reserves of trees and rocks in Vallingby, there is a large, bare asphalt school yard at Skarholmen. Where there were finely hewn stone retaining and dividing walls at Vallingby, there are pathetic wooden fences, already mangled and broken in many places, at Skarholmen.

The results of a survey of Skärholmen center residents made by students in educational psychology at Stockholm University depicted lonely, bitter denizens of a cramped concrete universe who were further frustrated by their lack of extra money to spend at Skarholmen’s only abundantly provided activity – shopping. They complained that the youth center was too small and inadequately equipped to interest older youngsters, that little other recreation was yet available, and that Skarholmen’s government centers for child day care, one of the most admired of Sweden’s social programs, had space for only a small fraction of the children whose mothers worked. Many other children were simply left alone much of the day to wander in the center’s stores or play with shopping carts on the escalators and in the elevators. Only five percent of the residents interviewed by the Stockholm University students said they were satisfied with life in Skarholmen.

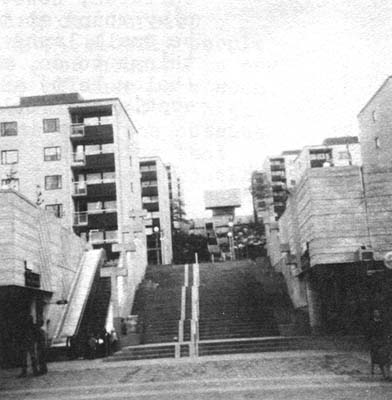

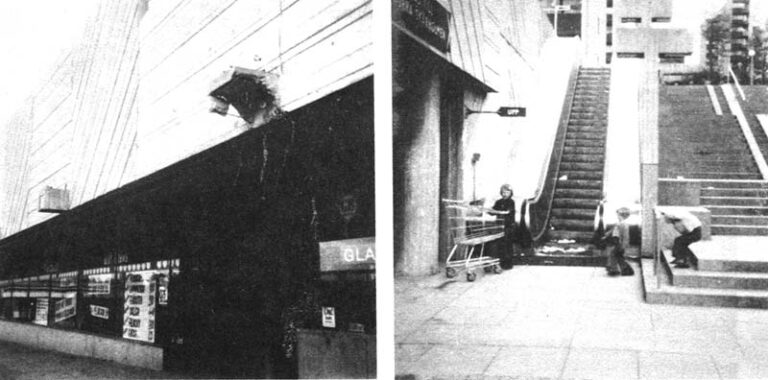

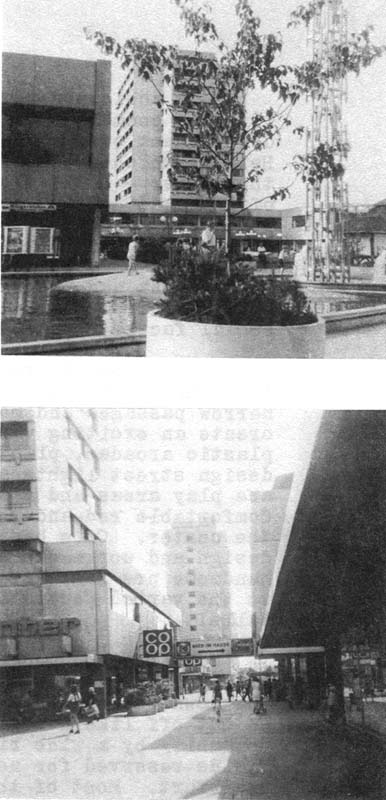

The Monolithic Scale of Skärholmen

Long, stark lines of apartment buildings on hill behind Skärholmen center.

Long stairway up the hill from Skärholmen center viewed from top and bottom. Elevator is hidden behind the stairs.

Children in Skärholmen

This dissatisfaction is all the more distressing because Skärholmen is a far cry from the inner-city slums, public housing projects and cracker box suburbs that low income families inhabit in the United States. Compared to them, Skärholmen is an impressive exercise in physical planning. Yet this is also part of Skarholmen’s problem. Its highly detailed physical design was based on planners’ notions of community, rather than on how people actually live. The result is a community of concrete rather than people, an inflexible world full of unexpected social problems, such as the crowding of too many low-income and fatherless families into massive housing with too few services for them.

Similar shortcomings in Swedish planning can be seen elsewhere in its new communities. At Vallingby, elderly people were provided with what physically was quite good housing in new buildings subsidized by the government. Many of them were soon quite unhappy, however, because they had been isolated in high-rise buildings where often their only contacts with the outside world were visits from their social workers. Realizing that something had gone wrong, the planners tried to improve housing for the elderly in Skärholmen by providing them with more open apartments in much lower buildings around attractive gardens. This housing remained segregated, however, in the middle of Skärholmen center where no one else lives, and its residents are left particularly alone when the center becomes a virtual ghost town after the stores close every night. It is true that the elderly do not want to be too close to families with noisy children, but such complete isolation reinforces the sense of rejection that they feel in Sweden, where, ironically, the physical needs of the elderly are better taken care of than anywhere else in the world. In designing their physical environment, however, Swedish planners have not come to grips with the more important social problems the elderly have.

This failure of Swedish planners to deal with the social dimension of new community building is not so noticeable in a community like Vällingby because of the redeeming value of so much natural beauty so close at hand and the abundance of thoughtful and attractive physical amenities built into the project. But as financial considerations force a reduction of those amenities in later projects like Skärholmen and such increased crowding of big buildings that nature is squeezed out, the new Swedish suburbs become less promising communities and more like the “concrete ghettos” that an increasingly critical local press is calling them. Outside shopping hours in their highly developed marketplaces, there is too little sense of community or joy of living in Skarholmen, or in the first neighborhoods being built now around the site of Hansta, the next new suburban center located far to the northwest of central Stockholm.

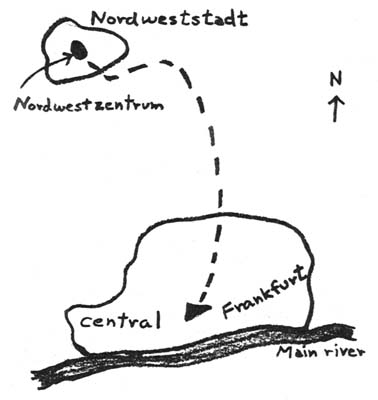

Nevertheless, elsewhere in northern Europe, where crowded city slums and sprawling, disorganized suburbs were too long the alternative to the physically superior if increasingly spiritless Stockholm suburban centers, several of the undeniably successful aspects of Swedish new community building are now being copied. Planned new suburbs with commerce, employment, public transportation and protected parkland are being built around stops on the subway and commuter train lines leading out of several northern European cities, including Oslo, Copenhagen, Frankfurt and Amsterdam (where a subway is now under construction).

Each or these new suburbs also are disappointing, however, in the same way that Skärholmen is. The planning has been too strict and the resulting communities too cold and inflexible. Financial limitations – the same high cost of labor as in Sweden plus the expense of assembling land in cities that had not been stockpiling it as Stockholm had – and the need to provide low-cost housing for the low-income families who must be accommodated first in these new communities are producing overly monotonous buildings and communities with too little visual appeal and too few social services.

Thus, at Bijlmemeer, Netherlands, going up where a subway stop eventually will be located on the outskirts of Amsterdam, inhumanly large slab buildings are being constructed around too little green space in the continent’s most 1984-ish development. At Albertslund, Denmark, on the highly efficient commuter train line out of Copenhagen, the profiles of the buildings have purposely been kept low in a community where nothing is more than four stories high, and a long drainage canal has been landscaped and lines with homes and shops to provide an Amsterdam-like center for the community. But the low buildings are still so monotonously similar and depressingly gray in their pre-fab concrete construction that they are just as foreboding as Bijlmemeer’s looming monsters. The interior courts around which most of the Albertslund housing has been arranged in squares and rectangles are as bare and grim as prison yards. A walk along any of the well planned but badly landscaped pedestrian paths leads only to a maze of look-alike passages and buildings.

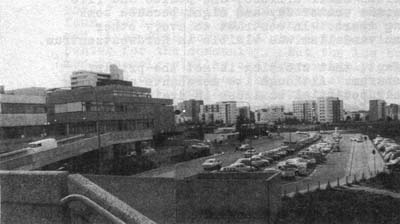

Nordweststadt, West Germany, at the end of one of the subway lines radiating from the center of Frankfurt, is a curious jumble of both big and little, densely packed and widely spread out buildings in rather extreme architectural styles covering several decades of new community experimenting both before and after World War II in Germany. There are the long, low-slung bands of two-story housing produced during Germany’s suburban experiments of the 1920s, and the high apartment towers put up since the post-war decision to build a community of 60,000 people in a “new town” built around the old experimental suburbs. Nearly all the housing is multi-family and much of it has been constructed by West Germany’s giant public housing corporation, Die Neue Heimat.

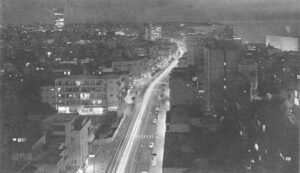

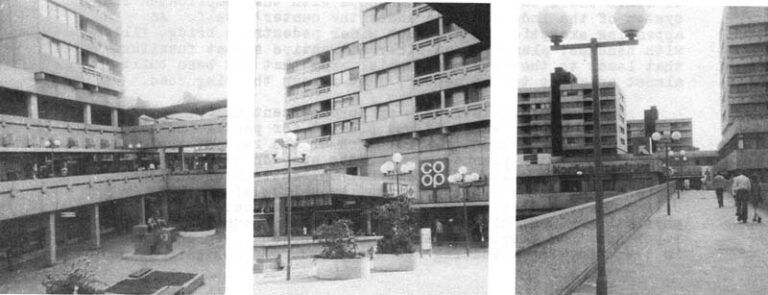

Nordweststadt would be meaningless as an urban place were it not for the location in its center of Nordwestzentrum (northwest center), the closest anyone has yet come to creating in a “new town” center both the appearance and social vitality of a real city “downtown.” Nordwestzentrum is a handsome example of the latest physical design techniques. Hidden under the pedestrian decks are the subway station, parking levels for 2,350 cars, a sunken road system for delivery trucks and a bus station. On the various pedestrian levels are stores, offices and public services, with several apartment towers rising above everything else.

The center is much more than an architectural sculpture or a collection or stores, however. It is also a working social organism. Nordwestzentrum has had, since the completion of its first stage, the kind of public facilities and social life so direly missing, for instance, at Skarholmen. There is a huge multi-level community center with two assembly and entertainment halls, clubrooms, youth rooms, workshops, restaurant and pub with outdoor terrace; a social services center with clinics, nursery, kindergarten, youth house, gymnasium, workshops, laboratories and club for the elderly; a trade school and school of social work, both with dormitories; an indoor swimming pool and a large library. In addition to four department stores, 60 shops and 14 restaurants, pubs and outdoor cafes, there are 178 apartment units, various small offices, and police and fire stations. People are in the center day and night because something is always happening there. In contrast to every other center visited, almost no vandalism was visible in Nordwestzentrum.

Surveys show, in fact, that shopping is not the primary attraction of Nordwestzentrum. Although its merchants are doing well enough, much of their potential business is drained off by Frankfurt’s recently renovated retail center downtown, which just happens to be at the other end of the 20-minute subway ride downtown from Nordweststadt. What the residents really like and make good use of in Nordwestzentrum are the social facilities. Nordweststadt residents of all kinds go there for entertainment, exercise, meals out, socializing or help with personal problems.

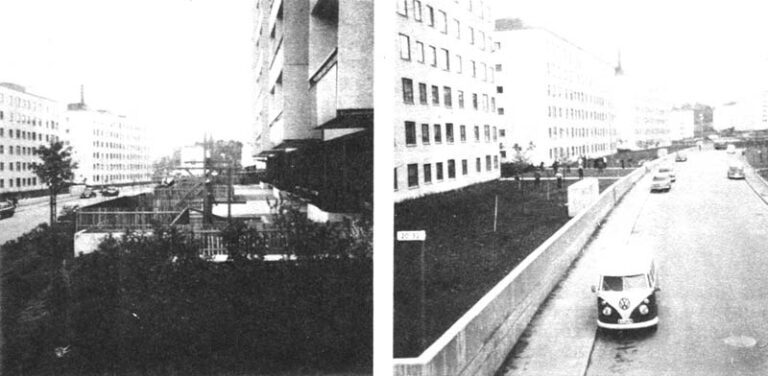

The world of Nordwestzentrum

Its many visible levels include sunken play areas for children, broad shop-lined pedestrian malls, narrower balconies and bridges of the upper shop and office levels, and apartment towers. There are pedestrian bridges to bring residents from nearby housing over the roadway that encircles the center. Outdoor cafes, plantings, fancy street lamps and a fountain, along with brightly colored overhangs, help make the center interesting to look at. Unfortunately, the circle roadway and nearby bare ground where future development has not yet taken place cut off the fortress-like center from much of the project’s housing. Many people park their cars along the roadway outside rather than cope with the complicated ramp and elevator system of the parking garages under the center

To achieve Nordwestzentrum’s enviable balance of social life and commerce, the Frankfurt city government turned its development over to the public housing corporation, Die Neue Heimat, which created a subsidiary that built and still owns the center – lock, stock, and barrel. All the shops, apartments, offices and public facilities have been rented rather than sold to those who occupy them. Even the city of Frankfurt must rent the police and fire stations. The public housing corporation has thus been able to strictly control the center’s design, development and present use to keep commercial interests from taking control of it and to make certain that all the desired social facilities were provided.

The process produced a center that is pleasant, even exciting, to be in. Its many varied levels, spacious malls, narrow passages and meandering pedestrian balconies and bridges create an exciting variety, with color added by bright red plastic arcades, planters of flowers everywhere and modern-design street lights and other fixtures. On sunken mall levels are play areas and a miniature amusement park for children. Comfortable red-and-white plastic benches are placed throughout the center. Care has been taken with and money spent on the design and workmanship of the entire center, from the unusually handsome pre-cast facades and balconies of the apartment towers to the varied decorative concrete tile floors of the pedestrian malls.

The raised decks and apartment towers of the center give it the bulk and visual grandeur necessary to make it look like the downtown of Nordweststadt. At the same time, however, it is cut off like a medieval fortress from the rest of the community by a wide ring road around it and several empty fields reserved for new housing and a freeway from central Frankfurt. Most of the narrow concrete bridges to carry pedestrians out of the center and over the road lead only to the open field and small open parking areas in which many shoppers prefer to leave their cars rather than cope with the complicated ramp system of the indoor garage under the center itself. An appealing exception is the much wider pedestrian bridge filled with benches, planters and other attractive street furniture that leads to the only residential area that has been built almost adjacent to the center, just across the ring road.

The undeniable strength of Nordwestzentrum is, however, the obvious way in which it was planned for people and has itself become a living community. Too much of the rest of northern Europe’s strictly planned new suburbs are, on the social level, disappointingly cold and impersonal collections of buildings. While avoiding the problems caused by a lack of planning in the United States, they suffer from the consequences of too much physical regimentation. They are not real communities. It is important that American planners not overlook this shortcoming in the otherwise appealing new urban order of northern Europe.

Received in New York on August 16, 1972

©1972 Leonard Downie, Jr.

Leonard Downie, Jr. is an Alicia Patterson Fund Fellow on leave from The Washington Post. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Downie, the Post and the Alicia Patterson Fund.