Marcos Breton

- 1996

Fellowship Title:

- Lost Field of Dreams

Fellowship Year:

- 1996

- Co-Fellow: José Luis Villegas

The Prospect

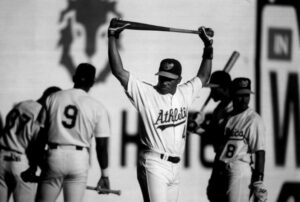

By Marcos Bretón with photos by José Luis Villegas CERES, CA. – Ninety acres of Stanislaus County alfalfa swayed in the late summer breeze as four shirtless young Dominican men walked in bare feet to the field’s edge. With three carrying kitchen chairs and another a boom box, the men sat in a semicircle – oblivious to the curious farmers rumbling by in their half-ton trucks – as Caribbean music played. They were indeed an odd site at harvest time in the middle of California’s lush Central Valley, a 90-minute drive either way from Sacramento to the east and San Francisco to the west. Miguel Tejada, of the Class A Modesto Athletics, stretches before a game, his teammates in the background. An amazing defensive shortstop, Tejada also shows great power at the plate. It is early in the 1996 season and he is showing the confidence of a player on the way up. But here – in front of a faded green and white bungalow, across from the local sewage treatment plant, six miles south

Lost in New York: Baseball’s Latin Ghetto

By Marcos Bretón with photos by José Luis Villegas NEW YORK – They are discards and runaways, lost souls and drug dealers, day laborers and illegal immigrants, and to a man, old before their time. José Santana, 24, waits for a snack at a fast food truck during the intermission of a double-header in South Brooklyn. Santana, like many of the players, briefly was a minor leaguer before being released due to a knee injury. Each year, hundreds of penniless, ill-educated boys from the Dominican Republic are brought to the United States by major league baseball. And each year, all but half a dozen or so end up embodying the underside of America’s national pastime: Living, breathing relics whose dreams of escaping poverty were turned to nightmares when baseball deemed them not talented enough, dissolved their contracts and their only means of living in the United States legally. A stripped automobile sits abandoned near the Norwood subway station in south Brooklyn, New York. The neighborhood is home to a predominately low-income Latin community, including many

The Imports

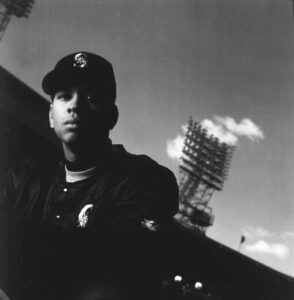

By Marcos Bretón with photos by José Luis Villegas There was a time when America’s game was played by only three kinds of people: White Americans, black Americans and Latins. American-born, but of Dominican ancestry, Alex Rodriguez is a shortstop for the Seattle Mariners. He signed right out of high school with the team for $1.3 million in 1993. It goes without saying that the experience of white Americans in major league baseball is well-known. And, while early black players were grossly underpaid and exploited, their integration became a noble act that benefited the nation as a whole. Luis Olmo, a Puerto Rican baseball player with the Brooklyn Dodgers, was one of a handful of U.S. major leaguers to agree to a higher salary to play in Mexico. He left the Dodgers in 1946. Major League Baseball banned players from returning to their home countries to play, but relented two years later after Latin players threatened to sue. Olmo later returned to the Dodgers in 1949, but was given little opportunity to play. Now 77,

The Dream: Trying to Make it in the Major Leagues

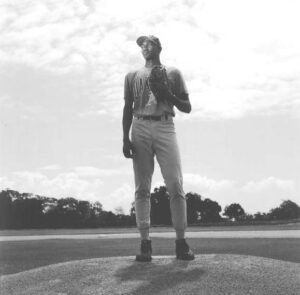

By Marcos Bretón with photos by José Luis Villegas La Victoria, Dominican Republic – It is after dark on a humid and still March night – the last night before 11 young men would fly to America on a trip that could forever change the course of their lives. All that afternoon, an uneasy tension had permeated the Oakland Athletics’ baseball complex, particularly after a busload of younger players too raw to make the journey had gone home for the weekend. So had all the coaches, managers and administrators. “When you’re at this level, nobody can do anything for you because you are nobody,” said José Paulino, 19, a new recruit from the Dominican Republic at his first major league spring training camp. “This is the profession I chose and I don’t know how to do anything else. And they are the ones who decide whether you are going to today, tomorrow or the next day.” The only ones left are the “prospects,” the young men given the precarious opportunity of playing a winner-take-all game