By Marcos Bretón with photos by José Luis Villegas

NEW YORK – They are discards and runaways, lost souls and drug dealers, day laborers and illegal immigrants, and to a man, old before their time.

Each year, hundreds of penniless, ill-educated boys from the Dominican Republic are brought to the United States by major league baseball. And each year, all but half a dozen or so end up embodying the underside of America’s national pastime: Living, breathing relics whose dreams of escaping poverty were turned to nightmares when baseball deemed them not talented enough, dissolved their contracts and their only means of living in the United States legally.

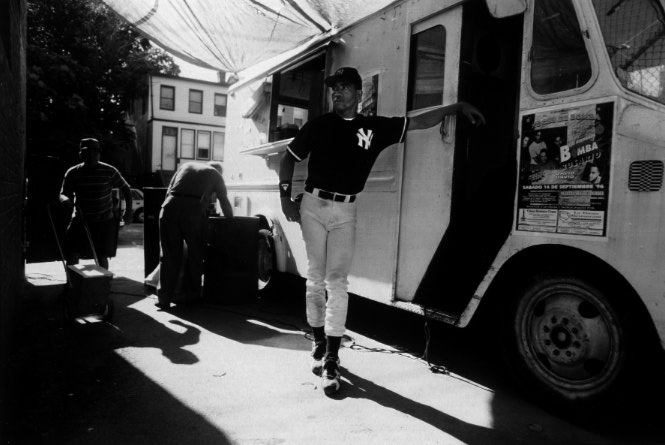

No longer of use to win games or help train other prospects, the Dominican players are punched a one-way ticket home. But many – unwilling to face the uncertain shame and the certain poverty that awaits them there – sneak out of airport terminals to remain illegally in the United States.

“You come here with the idea of making it, and then you don’t,” said Jorge Moreno, who was cut by the Detroit Tigers in 1994 after playing four minor league seasons. “I felt ashamed when I was released. I won’t deny it, I cried.”

Like Moreno, most find their way to New York City, blending into barrios that now make up the largest concentration of Dominicans in the United States:

from 130th Street in Spanish Harlem, up 80 blocks through the city’s highest homicide rate, beyond the Harlem River in the Bronx, to the slums near Yankee Stadium and across town in Brooklyn. (According to U.S. Census figures, there are about 600,000 Dominicans in the greater New York area.)

“Out of 10 (Dominican players) who are released, I’d say nine stay here” illegally, said Ron Plaza, a former major league manager and now a roving instructor with the Oakland Athletics. “They would rather live in the worst areas of New York than go back home You can’t handcuff them to the plane, so there is very little we can do.”

Now toiling in a Brooklyn garment factory, Moreno said: “I couldn’t stay in my country because when you stop being a ballplayer, they don’t like you as much. It’s like the people who wanted something from you then make fun of you when it’s over.”

While Dominican players face the same long odds of making it to the big leagues as their American counterparts, major league baseball employs a different strategy when recruiting Dominican players that makes their failure all the more tragic and, in many cases, inevitable.

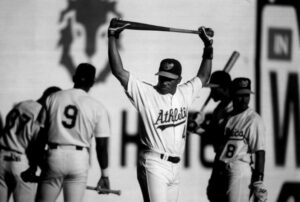

The majority of Latin American players brought to the United States – about 700 each year, most of them from the Dominican Republic – never had a chance of succeeding. Despite what they’ve been led to believe by major league scouts, their main purpose is to help train other players. Dick Balderson, vice president of player personnel for the Colorado Rockies, described the Dominican recruiting strategy as a “boatload mentality.”

“Instead of signing four (American) guys at $25,000 each, you sign 20 (Dominican) guys for $5,000 each,” Balderson said. “The unfortunate thing about this game is that there are so many people yearning to play it.” Especially in a country like the Dominican Republic, where $1,000-a-year wages are the norm and baseball is a religion practiced by the impoverished – a fuente de vida (a fountain of life).

Explaining how the strategy began, Plaza of the Oakland A’s said: “When we first went to the Dominican in the early 1980s, we signed a lot of guys because we wanted to have our own squad because we didn’t want to have a co-op with another team A lot of mistakes were made and we weren’t sending a caliber of player (that was going to be successful). It’s unfortunate.”

Defending the strategy, Sandy Alderson, general manager of the Oakland A’s, said: “It’s a reaction to the cost of player development in the U.S. Part of that cost relates to the escalation of free agent salaries and increases in signing bonuses at the amateur level.

“If you are developing two or three players from traditional domestic sources and you can add just one player to that resource pool every year, then, in effect, you’ve increased your productivity.”

Further, officials in major league baseball say, though the recruitment strategy may be imperfect, there are always kids who defy the odds and make it. And because of this strategy, the officials added, there are more Latin Americans in the major leagues than ever. Indeed, nearly one in four major leaguers today is Latin American, the majority from the Dominican Republic.

Still, for every Ramon Martinez of the Los Angeles Dodgers or Sammy Sosa of the Chicago Cubs, there are hundreds of Dominican players who never made it and now try to survive an underground existence in New York City. With little education, unable to speak English and in the country illegally, survival takes the form of fake Social Security cards, assumed names, low-wage jobs, tenements with bolted doors and constant fear.

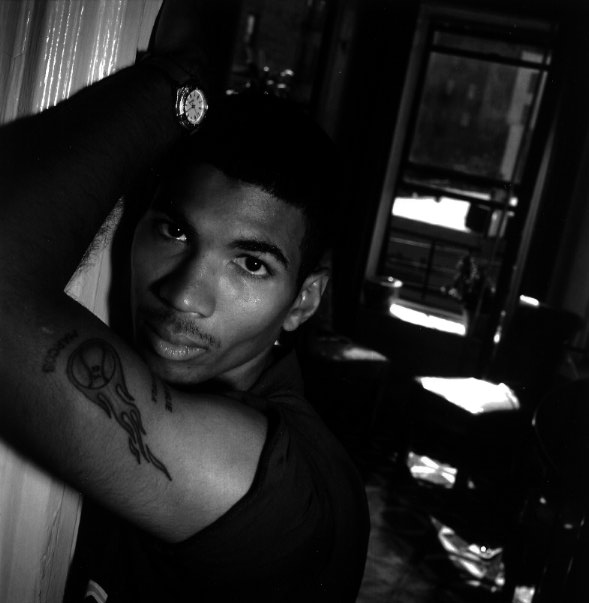

“There are so many guys here who are lost,” said Carlos Made, formerly of the Oakland A’s. “They are completely lost.”

Victor Martinez, who made his way to New York after being released by the Chicago Cubs in 1988, said: “What I found when I came to New York was an atmosphere of corruption. The only friend you have here is the money in your pocket.”

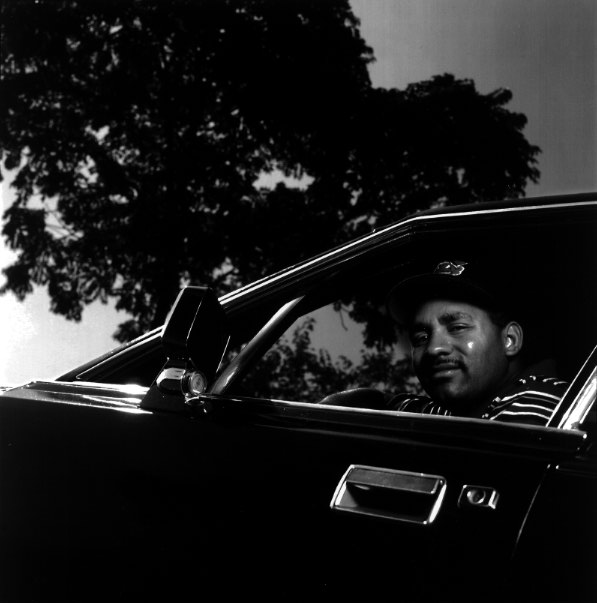

A self-described has-been, Martinez bears the scars of his failed baseball career.

His once 6-foot, 170-pound baseball-playing frame has fleshed out by 50 pounds. His reflexes have been slowed by years of sitting behind the wheel of his taxi in his ever-present T-shirt and warm-up suit. His deep brown eyes now bare the world-weary quality of someone who has sold drugs and been robbed with a gun pointed at his head.

“Everyone in my family, all of my cousins here, were dealing (drugs) when I got here so I went into that life also,” Martinez said. “When you’re young and inexperienced, you’re hungry and you see other people making money, you want to make money also. So you fall into that life. A lot of guys who played baseball do.”

And more than ever today.

To tell that story, one has to begin in the destitute playgrounds of the Dominican Republic, a Caribbean island nation of 8 million people that produces endless tons of sugar. During the early part of this century, when the United States occupied the country, baseball was imported and fanatically embraced.

During the late 1950s, after the San Francisco Giants found Hall of Fame pitcher Juan Marichal and the three Alou brothers, several teams began their own hunts for Dominican talent.

By the mid-1980s, following the success of the Los Angeles Dodgers and Toronto Blue Jays with Dominican players, scouts from every major league club fanned out across the island.

Today, with all 28 big league teams allotted 26 visas each for foreign players, the high-stakes race for talent adds up to about 700 Latin American kids brought to the United States each year. Most of the Dominican kids are signed to pro contracts before finishing high school. The results have been occasionally thrilling – a kid beating the odds to make the big leagues and millions of dollars – but mostly heartbreaking.

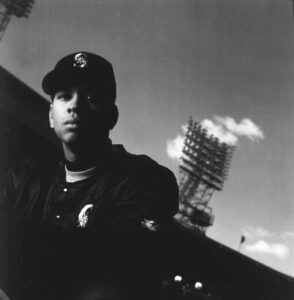

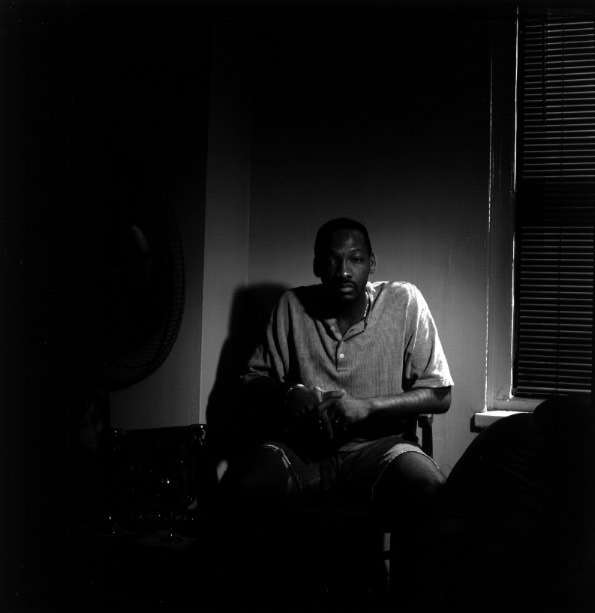

The heartbreak lives in men like Carlos Made and Jose Santana.

After being released by the Oakland A’s in 1989, Made fled to New York as an illegal immigrant. Now a legal resident, he is unemployed and supported by his American wife.

“My goal was to build a hospital in my town,” he said, recalling the millions of dollars he thought he would make playing baseball. “We are poor people and I really wanted to do something. To this day, whenever I play the Lotto, I still think of that hospital.

“Look at me now. I’m 30 years old and I’m finished.”

Santana, who was released by the Houston Astros last October, said: “I thought I had everything. All of a sudden I went from being a prospect to being released.

“I came here to New York because I wasn’t going to get stuck in the Dominican with no options. There is no life back there. I need to find that opportunity here.”

For Santana, he hopes that opportunity means a second chance at baseball. But with a surgically repaired right knee and at the age of 24, Santana is likely well past his usefulness to major league baseball. Each year, a fresh crop of hungry Dominican kids is brought in to replace players such as Santana.

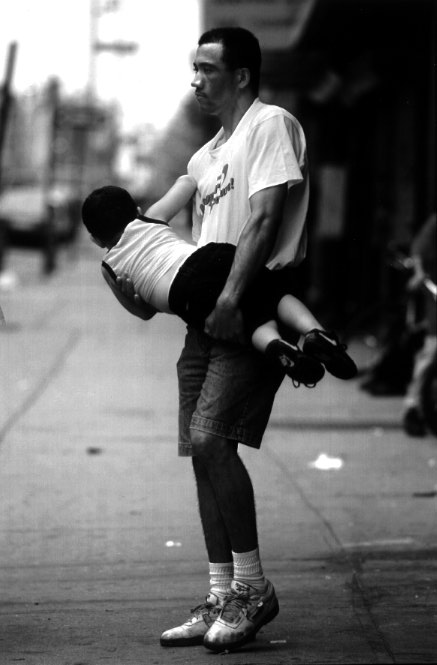

Refusing to give up, Santana toils in a semi-pro league filled with major league castoffs and has-beens. In between his weekend games at a park in Brooklyn and his dreams of a million-dollar contract, Santana earns $200 a week by sweeping and stocking shelves at a tiny Brooklyn grocery store.

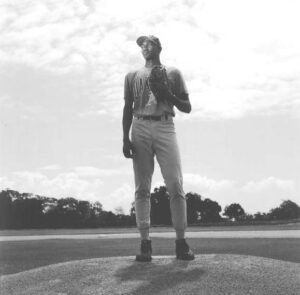

On the weekends when he’s wearing his stained, semi-pro uniform, Santana’s 5-foot-10, 170-pound body looks rock solid – his upper body tight and defined. In moments of inspiration, he can still move effortlessly toward the deepest part of the infield, backhand a ground ball and fire it to first for an out.

As Santana’s team prepared to play a game in early September, young Dominican men began arriving at the tattered Brooklyn park, where the Dominican flag flies in center field next to Old Glory. Several of the Dominicans bragged about how good they were, about how close they had come to stardom and how, with just one more chance, they might still make it to the big leagues. Like Santana, they saw their abilities far differently than those who cut them.

“Jose Santana, in the overall scheme of things, was just another player,” said Fred Nelson, assistant to the general manager for the Houston Astros. “He could catch the ball pretty well but he didn’t run particularly well Guys like that get eliminated from programs.”

Still, Santana remains undaunted.

“I know I have what it takes,” he said as he prepared for his weekend game.

Although he played well during the game, Santana made a throwing error that nearly allowed his opponents to tie the score. A few moments later, a teammate in center field badly overran a fly ball and allowed the tying run to score.

It was a typical game played by former prospects – a contest where bonehead plays dominated the flashes of brilliance. Santana’s team lost just as it began to rain

After the game, Santana and two of his teammates talked of the loss and of a different outcome if only some key players had showed up. One of them, a former minor league rising star named Elvin Paulino, was particularly missed. Paulino, who Balderson of the Colorado Rockies said had “major league power,” was about to make the Rockies when drinking problems forced his release in 1993.

Paulino admits he “screwed up.” He is now playing semi-pro ball in an attempt to make a comeback at age 28. Still, as he did when he was a professional, Paulino let his team down when they needed him.

“That happens a lot on Sunday games. Guys go out the night before and then they don’t show up to play,” Santana said. “I’m not going to do that. I’m going to keep working. I’m going to keep trying until I get my chance.”

Next year, Santana said he hopes to play in an independent league in upstate New York. He refuses to give up his dream. After all, it was the Americans who came looking for him with a pro contract to come play baseball in the United States.

As the rain began falling harder, Santana said to no one in particular: “I just need one chance. Just one.”

©1997 Marcos Bretón and José Luis Villegas

Marcos Bretón is a reporter and José Luis Villegas is a photographer with the Sacramento Bee. They are researching the forgotten legacy of Latins in American baseball.