By Marcos Bretón with photos by José Luis Villegas

CERES, CA. – Ninety acres of Stanislaus County alfalfa swayed in the late summer breeze as four shirtless young Dominican men walked in bare feet to the field’s edge.

With three carrying kitchen chairs and another a boom box, the men sat in a semicircle – oblivious to the curious farmers rumbling by in their half-ton trucks – as Caribbean music played.

They were indeed an odd site at harvest time in the middle of California’s lush Central Valley, a 90-minute drive either way from Sacramento to the east and San Francisco to the west.

But here – in front of a faded green and white bungalow, across from the local sewage treatment plant, six miles south of the city of Modesto – a budding baseball star sat with three of his countrymen from the Dominican Republic and watched the sun set.

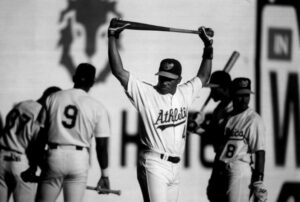

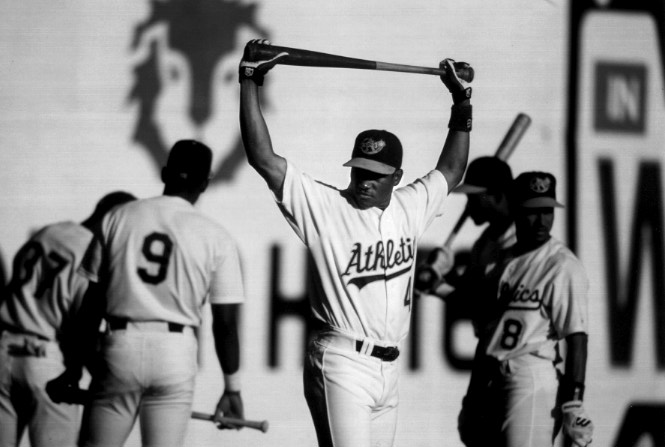

At 20, Miguel Odalis Tejada is the top prospect in the Oakland Athletics’ organization. And after a stellar season with the Class-A Modesto A’s, he was named by USA Today as the best minor-league shortstop of 1996 and by the Sporting News as one of five “can’t miss” prospects for 1997.

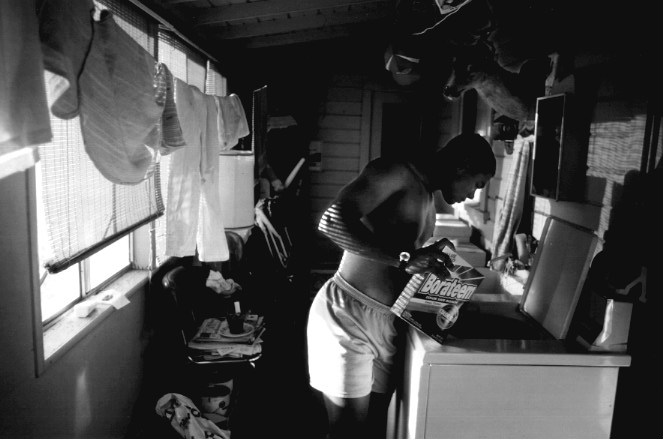

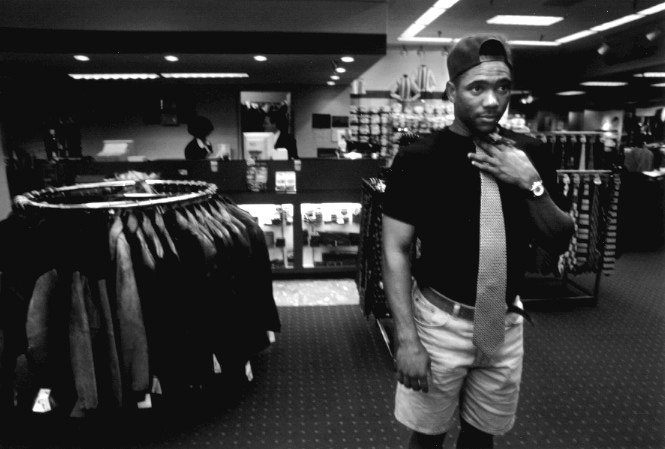

Unlike his American teammates, however, Tejada didn’t spend his days off driving to San Francisco. He couldn’t. Any extra money from his bimonthly salary of $350 was sent home to help his family.

And unlike American prospects of similar talent, Tejada does not have a signing bonus of six or seven figures sitting in a bank account. The A’s purchased his services for $2,000, the common market value for Dominican players.

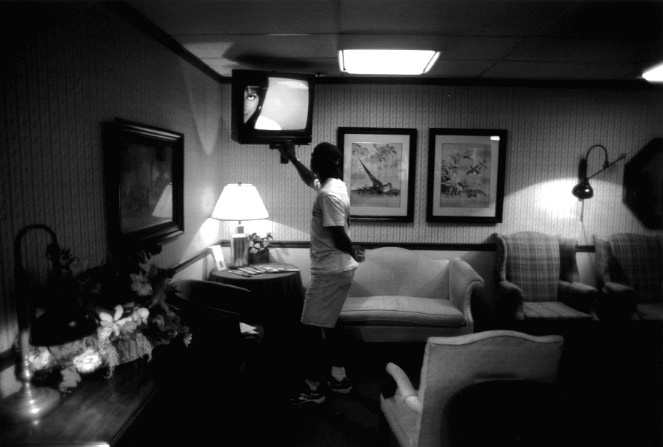

So instead, Tejada and his Dominican teammates spent their free time during the 1996 season in virtual isolation – on a Ceres farm, where the team boarded them – passing endless hours watching Spanish-language soap operas, cooking beans and rice and daydreaming of home while listening to Dominican songs.

This is life for Latin American players in the minor leagues today, no matter how good they are. For Tejada, who is from the Dominican city of Bani – a place where there is little electricity, few jobs and even less hope – such a life is very acceptable.

“We (Latin Americans) are playing their game in their country,” said Tejada, speaking in Spanish. “They run it, and all we can do is play. That’s all I’m trying to do You have to play as hard as you can to make your opportunities. That’s the way it is for us.”

But not everyone, including some established players, believes that is the way it should be for Dominican players or that it is fair that American teams sign bunches of Latin American kids for almost nothing.

Unlike in the United States, where teams are limited to signing players they draft in an annual lottery, most of Latin America is open to unrestricted recruitment, giving players no leverage to negotiate.

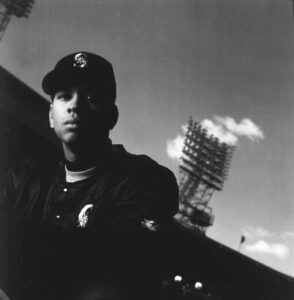

“You should not treat someone unfairly because they don’t have the leverage of some of the high school kids here, just because you don’t have the opportunity of going to Stanford” to play baseball, said Alex Rodriguez, shortstop for the Seattle Mariners.

“There is some great talent coming out of the Dominican for $1,000,” added Rodriguez, who is of Dominican ancestry and was born and reared in the United States. “There has to be some type of fairness.”

“It’s really crazy, because (if I had been born in the Dominican Republic), I’m sure I would have been a top prospect, but I would have gotten maybe a $5,000 signing bonus.” Instead, Rodriguez negotiated a $1.3 million bonus with the Mariners in 1993.

“The point is, it would have been a lot tougher road,” he said. A’s general manager Sandy Alderson defends signing players such as Tejada for $2,000. He said such players face longer odds of making it and are therefore a greater risk. Hence the lower signing bonuses.

“There is a very high attrition rate in baseball generally,” Alderson said. “(Latin American) guys are often signed very young and have cultural adjustments they have to make.”

“To put it not callously but directly, (Latin Americans) are higher maintenance. That requires not just money but a strategy, and it requires organization, good people and a whole additional layer of involvement with a player.”

Like many Dominican players, Tejada dropped out of high school at age 16 when a pro team came calling. Coming from a town with no job base and no opportunities, he said school seemed of no use to him.

Lacking options, he eagerly signed over the rights to his explosive speed and power for $2,000 and gladly began playing at the A’s training facility in the Dominican Republic. The signing bonus went to repair his family’s worn stone and mortar house.

Since last March, when Tejada arrived in Arizona for the annual rite of spring training, he has done all he can to make an impression, despite some obstacles.

In his first game against major-league players, Tejada came up to bat against the Mariners at Phoenix Municipal Stadium before 7,000 fans, the largest crowd he had played before. The public address announcer intoned: “Now batting, Jose Castro.”

In his next at-bat, with his name misspelled on the stadium scoreboard, Tejada hit a home run over the fence in left-center field. Even A’s slugger Mark McGwire noticed.

“After the game, he asked me where I was from,” Tejada said. “I couldn’t believe he was talking to me.”

At shortstop, the 5-foot-10, 190-pound Tejada showed his quickness and agility by making play after play.

Once the minor-league season began, Tejada proved spring training was no fluke by being named to the California League All-Star team.

In one game in May, he made an impression on Alderson, who was sitting in the stands.

Racing toward second base to make a double play, Tejada suddenly had to wait as a grounder rolled away from one of his teammates. As the ball was reclaimed and then thrown at Tejada’s feet, the runner gained ground. A collision among shortstop, baserunner and ball seemed imminent and a double play impossible.

But Tejada, standing on second base, caught the ball inches from the ground with his bare hand and simultaneously shifted his body out of the way. Standing flat-footed, he whipped his arm around and fired the ball to first for the double play. He seemed to do it all in one motion.

The reaction: The players on the Modesto bench leaped in unison to their feet. In the stands, Alderson turned to the person sitting next to him and said, “That might have been the best double play I’ve ever seen in my life.”

Still, Tejada’s coaches are most impressed with his willingness to work hard, combined with all that talent.

“He’s our shortstop of the future,” said Ron Plaza, a roving instructor with the A’s. “He’s special. Only God could give him what he has.”

In 1997, Tejada is set to play Double-A ball in Huntsville, Ala., in the Southern League. Despite the bright future, Tejada knows he is only a shattered ankle or blown knee from the poverty he left behind in the Dominican Republic, where before baseball he earned what he could by shining shoes.

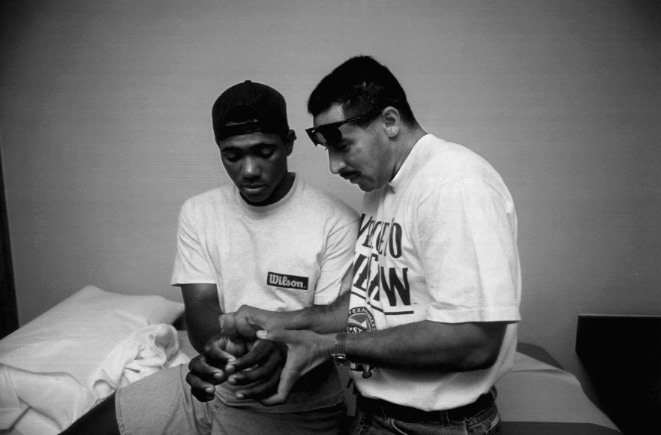

He has seen how quickly things can change. Near the end of his minor-league season, Tejada missed three weeks when he suffered a hairline fracture of his left hand, his glove hand, after colliding with another player during a double play.

And last May, his roommate and countryman Freddie Soriano broke an ankle in three places while sliding into second base. Leading the California League in stolen bases at the time, Soriano now faces an uncertain future.

So does Tejada. He says he and his coaches know there is no guarantee he will hit 20 home runs, drive in more than 70 runs or play spectacular defense in Huntsville the way he did in Modesto.

But somehow, Tejada says, he must succeed. As he sees it, making it to the major leagues is the only way he can ease the heartache endured by his father, Daniel, a construction worker.

Tejada lost his mother to intestinal problems four years ago because the family couldn’t afford to care for her adequately. His eldest brother died similarly. And another brother, the one who taught Tejada to play and love baseball, disappeared after leaving Bani to look for work and a way to help the family.

Each time he would mail part of his salary home, Tejada would sit down to listen to the same merengue song over and over again. The song, he says, reminds him of his dad.

It is about a young boy who begins an uncertain path in life and finds nothing as he expected – a life mixed with sadness and hope for the future.

The song could also be about Tejada.

Tejada says he sometimes feels he is carrying the expectations of his family and country of 8 million people on his shoulders. “I am their hope. They are all depending on me.”

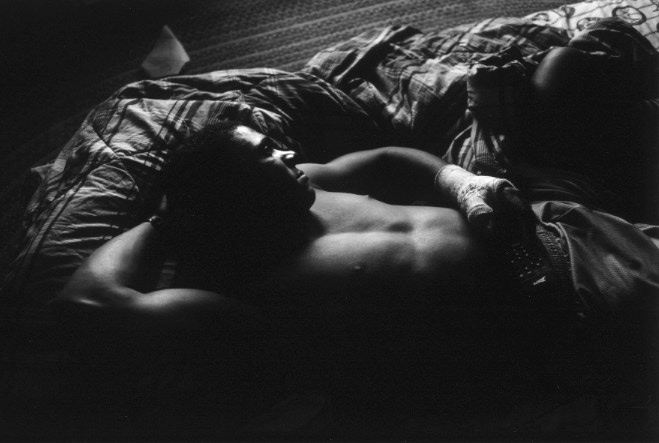

As he says this, he is lying on a mattress in the Ceres farmhouse. He does not say another word. He simply slips a pair of headphones over his ears and turns up the volume on his father’s song.

©1997 Marcos Bretón and José Luis Villegas

Marcos Bretón is a staff writer for the Sacramento Bee. José Luis Villegas is a photographer for the Bee. Both are working on a history of Latins in American baseball.