By Marcos Bretón with photos by José Luis Villegas

La Victoria, Dominican Republic – It is after dark on a humid and still March night – the last night before 11 young men would fly to America on a trip that could forever change the course of their lives.

All that afternoon, an uneasy tension had permeated the Oakland Athletics’ baseball complex, particularly after a busload of younger players too raw to make the journey had gone home for the weekend. So had all the coaches, managers and administrators.

The only ones left are the “prospects,” the young men given the precarious opportunity of playing a winner-take-all game of skill – a chance to fulfill the only dream they have ever had.

Making it in the major leagues.

They know the odds. A staggering 98 percent of the 700 mostly destitute Latin American men brought to the US. every year are released after only a short time in the minor leagues.

They return home to scratch out a living somehow – in the nickel mines, the sugar cane fields or the textile mills of a region that has a per capita income of only $1,000 a year. Many others will stay in the US. illegally, mostly in the ghettos of New York, where they will find themselves in minimum-wage jobs, or in jail. Or worse.

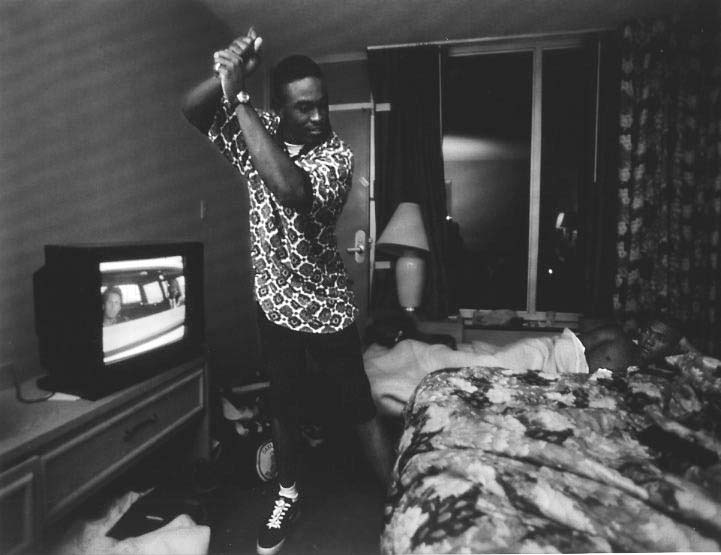

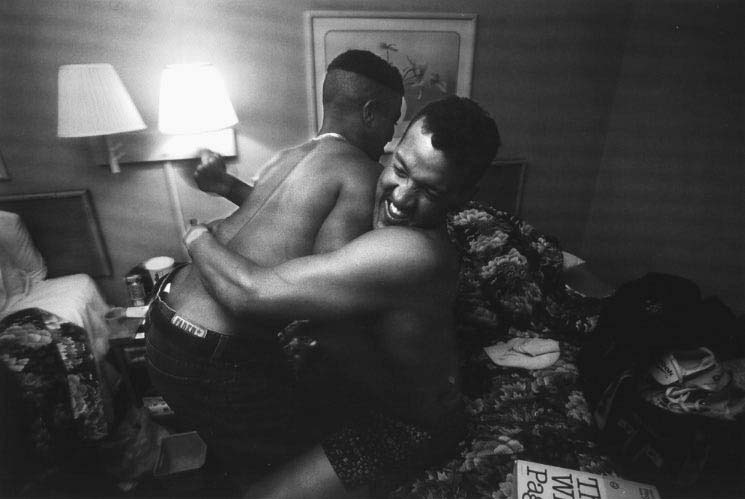

So it was that television could not hold the attention of the players tonight. Neither could lifting weights or reading. On this night, more than any night, they had to hear their music, they had to feel truly Dominican, one last time.

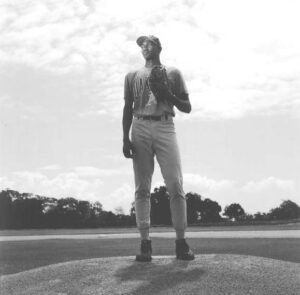

The gravel crunches beneath their feet as they plunge into the darkness, accompanied only by the piercing sound of crickets and the flash of fireflies. They ignore the squatters camped outside the complex gates, amidst the palm trees and underbrush that create a veritable jungle around Campo Juan Marichal.

Behind them, the five-acre baseball complex broods, surrounded by a chain-link fence and patrolled by a security guard with a sawed-off shotgun.

As they walk, however, the mood is light. The boys make jokes to each other as they turn on to an unlit, two-lane rural highway. It seems they laugh even louder as trucks and cars shoot by, their headlights blinding, their steel frames only inches away. “The drivers here are crazy,” shouts Juan Perez with glee. A 23-year-old Haitian/Dominican who grew up cutting sugar cane alongside his father, he lives in a home still owned by the company that employs his family.

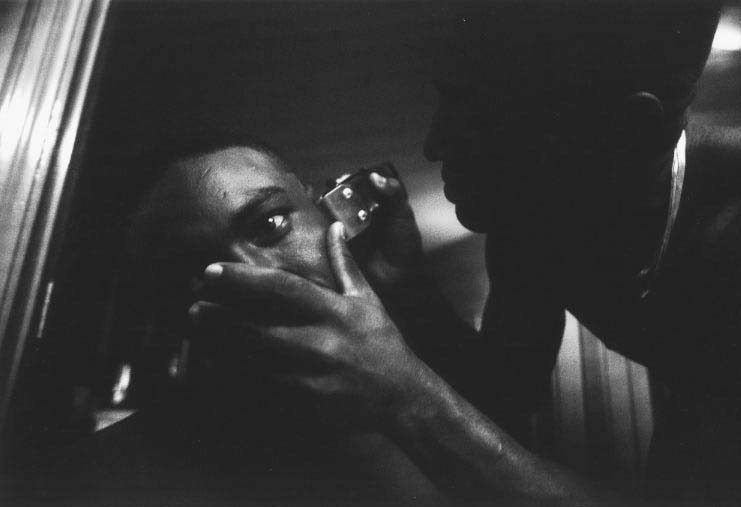

After a half mile, they reach the colmado, a roadside store. They take up stools in a patio section, walled off by metal bars and stacks of unsold Pepsi bottles. They sit stiffly, waiting while the proprietor searches for music he can play them on an ancient hi-fi. For the moment, all is still and it is as if the full weight of what is at stake is hanging over them, taking the very oxygen from their lungs.

Without warning, as it always is in the Dominican, the music is cranked up to ear-splitting decibels – in this case, a wild mixture of reggae and Spanish rap. At first, the faces of the young men flicker sternly in the light shone by a 60-watt bulb through a ceiling fan that, encased in cobwebs, looks as if it could come dislodged by its own movement.

And then, behind them, a little barefoot girl wearing only dingy bikini briefs, begins moving to the music. She is joined by a boy. Another girl. Then an expectant mother who seems barely out of her teens.

Soon the entire street is dancing, and bodies are throwing shadows on the walls of the colmado. They move in perfect unison in a scene of sheer joy amid the tenements, the open trash fire, the dirt road and the raw sewage. The young men smile, their eyes glistening now in the soft light.

Later, as they leave for home, as they prepare for America, it will be this that they carry – a heartbreaking reminder of how different they are from the world they are about to enter.

There is Perez, with his ever-present Walkman and oversized, wrap-around sunglasses. He pitches with the tenuous satisfaction of being able to buy medicine for his family and toys for his two children.

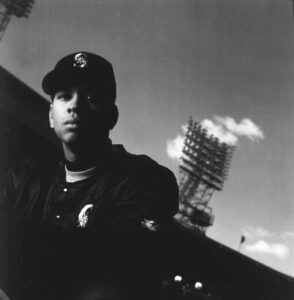

Arturo Paulino, a 21-year-old infielder known only as “Tobacco” to his teammates, who was about to make his first trip to the US. in 1994 when, in a head-on collision, his father died in a fiery car crash. Whatever money he saves from his $80-a-week meal money goes to his family, just as it did when he helped pay for his father’s funeral.

“I left them crying when I came here,” says Paulino, who though listed at 5′ 10″ and 150 pounds, seems smaller and more frail beneath his Athletics cap. “I carry my father around in my heart. My family depends on me now.”

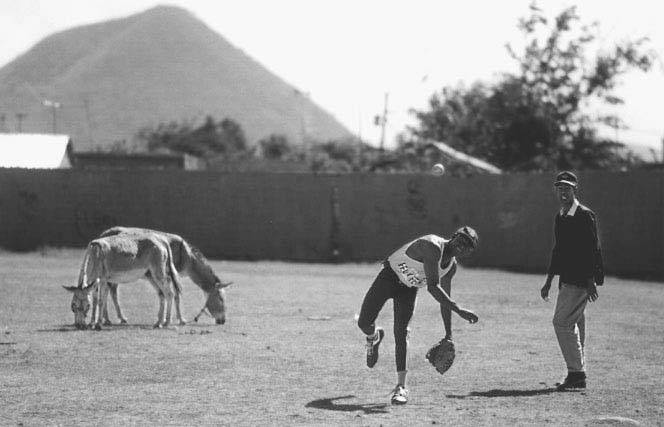

And then, there is Miguel Tejada, who was working as a shoeshine boy by the time he was five. Now, at 19, he has so much talent as a shortstop that, had he been born American and not Dominican, he would have commanded a $1 million signing bonus; instead, he signed with the Athletics for $2,000.

“They don’t give (Latins) the money because we don’t have the education,” says Tejada, who dropped out of high school when it became apparent that his future lies in baseball and not in books. “It’s very hard to swallow sometimes, especially if you know an American player has less ability than you.”

Nevertheless, hungry young men from the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Puerto Rico, Cuba and, to lesser degrees, Mexico and Panama, continue to come, continue to play America’s game as if their lives depended on it.

Tejada seems to be living proof of the correlation between poverty and success. Of his group, he is undoubtedly the best: a 5-foot-10-inch marvel with powerful shoulders, speed, grace and the ability to do what Americans love – hit long, majestic home runs.

And of his group, he had it worst.

The few quarters and dimes that he earned shining shoes went directly into his mother’s hand at the end of the day – hardly enough to feed his family.

Today, conditions are not any better. Inside his tiny home, rooms are separated by stained bed sheets and the roof is made of rusted, corrugated metal. Outside, he points to the naked children and smiles knowingly; he knows many of the parents cannot afford to clothe them, so they scamper among the squalor, unprotected from infection and the filth.

Is it any wonder then, that as Tejada and his teammates board their pre-dawn flight, they all know that as difficult as it is to leave, it would be even harder to stay – to be passed over.

At the airport, they are somber. In Miami, most of them forget to fill out their customs card and are detained by an impatient agent who barks out instructions in rapid English.

“That’s when it’s the hardest,” Paulino says. “Like when a coach explains something and you don’t understand what he is saying.”

From Miami to Dallas, Dallas to Phoenix, the players begin to droop, to grow increasingly silent. A group with razor-sharp wits in the Dominican, they are introverted and shy now.

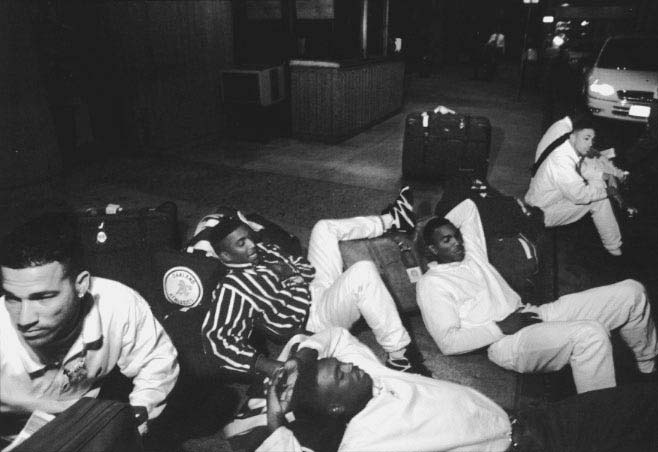

By the time they reach Phoenix for the annual rite of spring training, they are exhausted. They haul their tattered luggage – misshapen suitcases and duffel bags – from baggage claim and trudge to the passenger loading zone to await their ride.

A spectacular Arizona sun is setting as the prospects crane their necks, watching for the Athletics van that is to take them to their hotel. At first standing, arms crossed, in their cleanest jeans and cotton shirts, they would soon be sitting dejectedly on their bags as 90 minutes crawl by.

As they wait, Javier Gutierrez, a 20-year-old Venezuelan pitching prospect for the Seattle Mariners, walks toward the group and asks for help – his ride also has forgotten him. In a way, it is as if they are playing out some odd ritual, for in the 1950s – years before they were ever born – Puerto Rican baseball great Orlando Cepeda wandered lost in the streets of Kokomo, Ind., where he was sent by his minor league team; when he was stopped by a policeman, all he could say in his fractured English was, “Kokomo Giants.”

Not much changes in 40 years. Although fortunately for these prospects, their ride did come, albeit two hours late. They would eat their only meal of the day at the neighborhood Coco’s. And from there, in the coming days, they would do almost everything together: visit Scottsdale’s upscale indoor shopping mall. Taste Chinese food. And, inspired by infielder Freddie Soriano, take turns shaving their heads until they were all nearly bald.

Still just kids really. Until it comes to why they are here.

“I always put my desire to play baseball in front of everything else because I don’t want anything to get in my way,” Tejada says. “We have to play harder than they do. It’s like they own the house and we’re just guests. We have to play better so we can stay in the house.

“We have to play better.”

He gets his wish the next day.

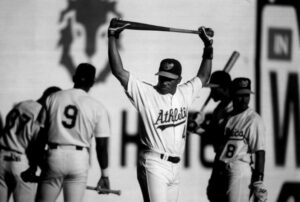

Along with three other Latins, he is called over to play in a game against major league players.

And when he comes up to bat for the first time at Phoenix Municipal Stadium, the public address system intones: “Now batting, shortstop, Jose Castro.”

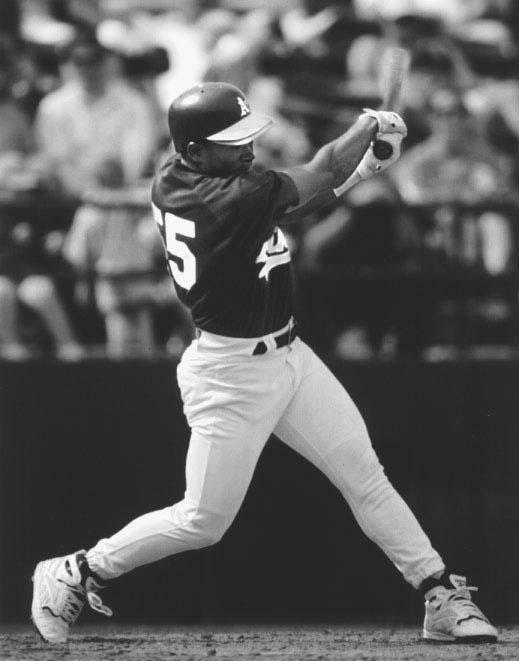

It takes an inning before they realize that Castro is really Tejada. And by then, looking like he was born to the game, he had already made the 7,000 fans in attendance buzz in awe on one single play:

From his shortstop position, Tejada veered far to his left, backhanded a scorching ground ball in the webbing of his glove and, in one single, fluid, beautiful motion, fired the ball to first for an out.

It’s been only two days since he left his barrio and his father, who earns about $75 a week doing construction work in the Dominican. His mother died four years ago.

“Miguel is a humble boy and I’ve tried to instill in him the confidence to succeed,” his father, Daniel, says. “The only way I could do that was to have a home where I worked and where there was love.”

But on this day, it’s a long way from that world.

As he stood in for his last at-bat against the Seattle Mariners, Tejada took a ball on his first pitch as the scoreboard flashed his name. It is misspelled.

And then, on the next pitch, Tejada swung and lifted a long, arching fly ball that soared high over the left fielder’s head, over the wall and the Miller Genuine Light sign.

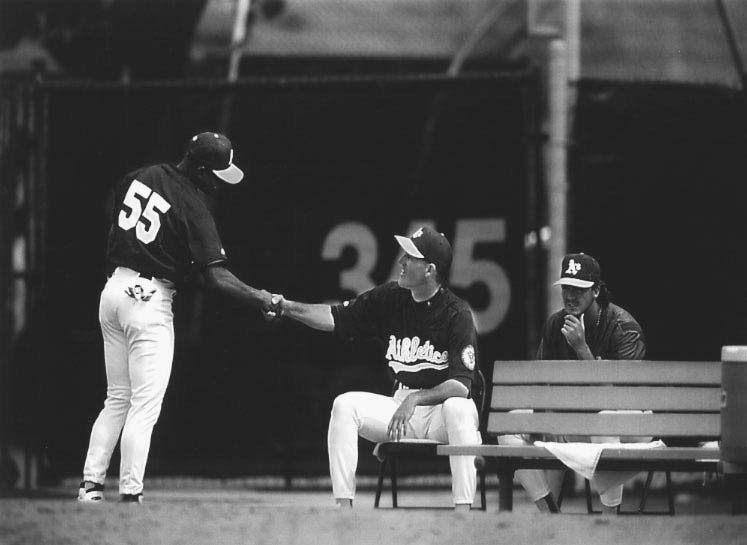

Three days later, veteran coaches who have worked with the best players of the last quarter century were giggling like school children when they considered Tejada’s future.

“This kid is one of a kind,” said Ron Plaza, former manager of the Cincinnati Reds and now an instructor with the Athletics.

“I would not be afraid to take that young fella with me right now and say, ‘come with me you’re going to be my shortstop in Oakland.'”

About as close to Tejada as any coach with the Athletics, Plaza nonetheless maintains a professional distance and, like most baseball people, knows little about Tejada’s background.

“I don’t know if he has one parent or two but I’ll tell you what, the kid has better ability than Ozzie Smith did,” said Plaza, of the legendary Cardinals shortstop considered by many the best of all time.

With the glee of someone describing a wonderful secret, like a hit song before it had ever played on the radio, Plaza then said: “You could be a blind man and hear the sound of Miguel hitting the ball and know that it’s him.”

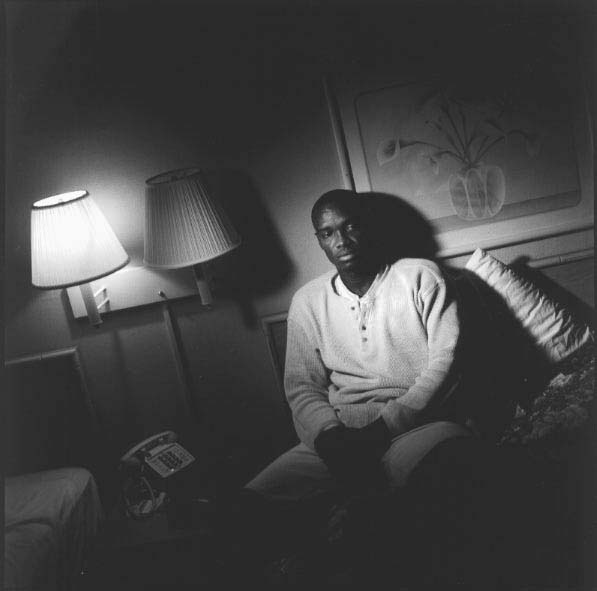

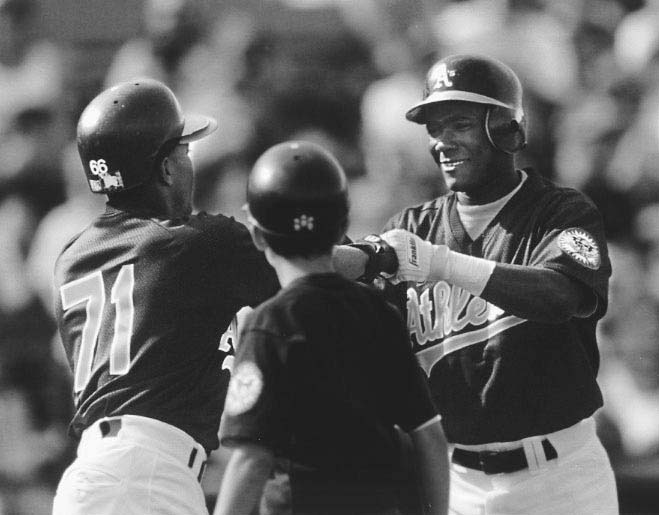

But as Tejada rounded the bases following his home run, he showed little emotion and there wasn’t even a flicker of a smile as he later ran past children asking for his autograph.

There was to be no celebration that day. Headed for the Athletics’ Class A team in Modesto, Tejada knew he was still a long way from any multi-million dollar contracts and only one torn knee ligament or broken limb from the poverty of his home.

And unlike several of his Modesto teammates, there is no six or seven figure signing bonus sitting in Tejada’s bank account in case it all ended for him tomorrow. For now, $80-a-week meal money will have to do for his expenses and to provide help for his family back home.

In the locker room following his big game, Tejada quietly removed his uniform. Suddenly, he looked small, young. The other players scarcely paid attention to him. For a moment, he was a titan; but now, he was only a dreamer. He carefully put away his clothes and, shoulders hunched, slowly walked to the showers.

©1996 Marcos Bretón and José Luis Villegas

Marcos Bretón is a reporter for the Sacramento Bee; José Luis Villegas is a staff photographer for the newspaper. They are researching the forgotten legacy of Latins in American baseball.