Richard Critchfield

- 1970

Fellowship Title:

- Food Population Crisis in India, Indonesia and Iran

Fellowship Year:

- 1970

Hello, Mister! Where Are You Going? The story of Husen, a Javanese Betjak Driver – Part II

Part Two: The City A study in two parts of the human impact of agricultural change and urbanization in the Javanese village of Pilangsari and the city of Djakarta Simprug “You are millions…But we are countless…”Aleksandr Blok In the heart of Kebajoran Baru, the richest and most aristocratic suburb of Djakarta, lies a large, low, swampy hollow which for most of its existence was planted in rice. Wet and steamy, sometimes flooded waist-deep by monsoon rains and too low to catch the cooling breezes from the Java Sea, the hollow for many years remained an enclave of green, pastoral countryside as the modern suburb, with its big, solid bungalows standing in their leafy, spacious compounds, grew up around it. Then, during Indonesia’s Moslem rebellion of the fifties and the population pressure of the sixties, as the trickle of job-seeking Javanese peasants into the capital city became a raging flood, a sprawling shantytown of densely-packed wooden and bamboo huts began spreading down the sides of the hollow, in time forming a community of several thousand inhabitants

Hello, Mister! Where Are You Going? The story of Husen, a Javanese Betjak Driver – Part I

Or ever the silver cord be loosed,Or the golden bowl be broken,Or the pitcher be broken at the fountain,Or the wheel broken at the cistern… The flow to the towns is already a major trouble in the poor countries of the world. In the 1970s it is liable to become an uncontrollable flood, and threaten real, red, raw, urban revolution.(The Economist, December 27, 1969) For capital to pay for weeding, harvesting and planting our rice, we depend mostly on what money our sons and daughters can send from Djakarta. Why, a fourth of the population of Pilangsari and almost a third of Karanggetas village across the river spend at least part of the year working in Djakarta, selling rice, street vending, pedaling betjaks – jobs like that.(A rice farmer in Pilangsari, August, 1970) Djakarta is hereby declared a closed city to all future jobless settlers. Urbanization has grown to such proportions it is endangering the public safety and order of life in the capital.(Lieutenant General Ali Sadikin, Governor of Djakarta, August 6, 1970) Contents Part

A Few Reflections: (Nobel Prize for Dr. Borlaug & Djakarta: The First “Closed City”)

1. Nobel Prize for Dr. Borlaug 2. Djakarta: The First “Closed City” October 30, 1970 A few days ago I received a cable from the Washington Star asking me to write a story on this year’s award of the Nobel Peace Prize to Dr. Norman E. Borlaug, an associate director of the Rockefeller Foundation and the distinguished plant geneticist who did much of the pioneering research that made Asia’s present “green revolution” of new seeds and fertilizer possible. “What’s it all about?” the cable ended. My instinctive, one-word reply to the question was “culture.” That what the green revolution was really all about was not only agricultural transformation but also very rapid cultural evolution, perhaps even upheaval, in hundreds of thousands of villages all over the world. And villages which until now had been pretty much left behind by history. The “hundreds of thousands” gave me a little pause, since my own experience had been almost entirely limited to two villages where I have been living much of the past year: Ghungrali-Rajputan,

A Doctrine For Revolution

June 12, 1970 Introductory note: The central, developing theme of previous articles in my study has been that if the governments of the poor nations cannot solve their problems of overpopulation and the social dislocation of the agricultural revolution, many of the world’s cities risk being inundated by a tidal wave of jobless men by the end of the 1970s, even if the poor two-thirds of the world manage to keep themselves fed. Calcutta may pass the 15 million mark, Buenos Aires 10 million, Cairo 6 million, with other cities in Afro-Asia and Latin America swelling even faster. In some cities, close to the majority of inhabitants may be uprooted peasants, a very large proportion of them without jobs. There must be reason to fear that in some cities riots and revolts will be fomented and that sometimes those of the rootless, jobless millions will join in. Chances are such revolutions will be called Communist, although it seems very unlikely they would be controlled by Peking, Moscow, Hanoi or Havana, all equally affected by the

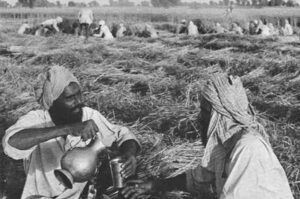

Sketches Of The Green Revolution – Part IV

Part Four: The Harvest A study in four parts of the human impact of the new seeds and methods of cultivation in Ghungrali-Rajputan, a prosperous farming village on the Punjab Plain in Northwest India The tractor and the huge red cutting machine came over the road and into Charan’s fields, a great crawler moving like an insect, with the incredible strength of an insect. It crawled into the wheat field; the diesel engine puttering while it stood idle, thundering when it moved and then settling down to a droning roar as it began to reap the golden wheat. The thunder of the engine’s three cylinders, with a pressure of eighteen hundred pounds per square inch, sounded throughout the plain as the fuel exploded and produced heat, converting chemical energy into mechanical energy and providing a power stroke to the reaper’s great knife, which slashed back and forth eight hundred strokes each minute. The four red-painted rakes rotated like a fallen windmill, guiding and sweeping the wheat into the great knife and beyond into sheaves on