Or ever the silver cord be loosed,

Or the golden bowl be broken,

Or the pitcher be broken at the fountain,

Or the wheel broken at the cistern…

The flow to the towns is already a major trouble in the poor countries of the world. In the 1970s it is liable to become an uncontrollable flood, and threaten real, red, raw, urban revolution.

(The Economist, December 27, 1969)

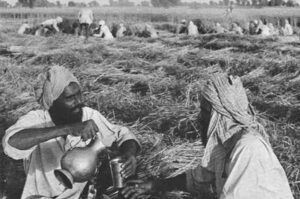

For capital to pay for weeding, harvesting and planting our rice, we depend mostly on what money our sons and daughters can send from Djakarta. Why, a fourth of the population of Pilangsari and almost a third of Karanggetas village across the river spend at least part of the year working in Djakarta, selling rice, street vending, pedaling betjaks – jobs like that.

(A rice farmer in Pilangsari, August, 1970)

Djakarta is hereby declared a closed city to all future jobless settlers. Urbanization has grown to such proportions it is endangering the public safety and order of life in the capital.

(Lieutenant General Ali Sadikin, Governor of Djakarta, August 6, 1970)

Contents

Part One:

- The Village

- God’s Will Be Done

- Homecoming

- Husen

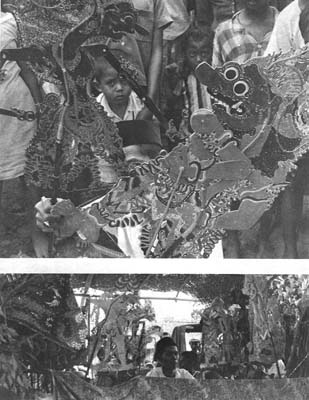

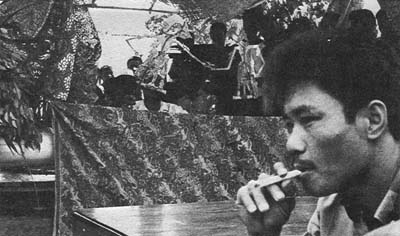

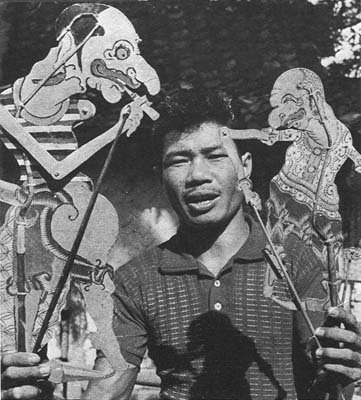

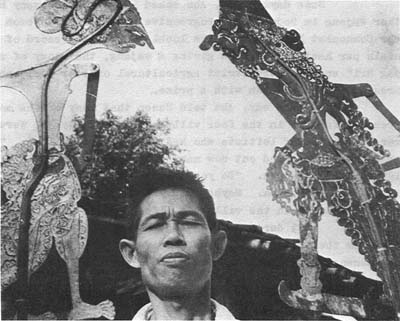

- Pa Lojo and the Sandiwara Troupe – The Shadow Play

- Abu and Father

- Return to Djakarta

Part Two:

- The City

- Simprug

- $40 and a Wedding

- Ring

- Bantjis

- Riot

- Tjasta

- A Closed City

- The Java Bar in

- Tandjung Priok

- To Sea in Kali Baru

- My Son, My Son

- Return to Pilangsari

Part One: The Village

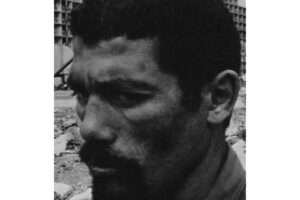

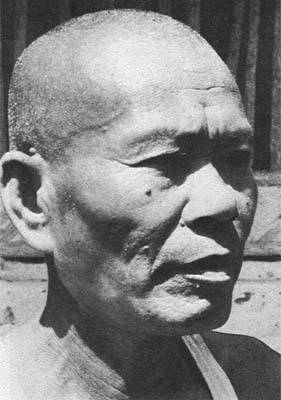

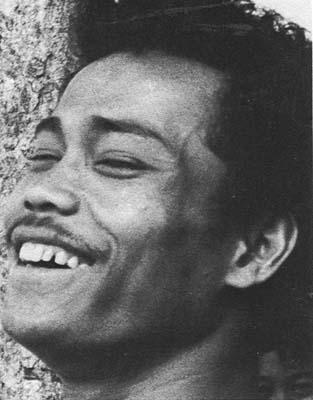

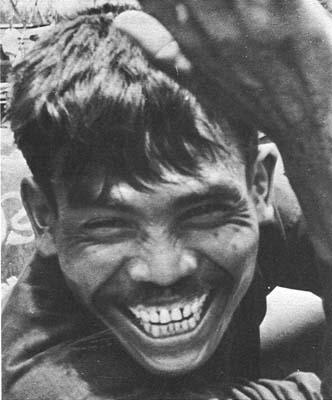

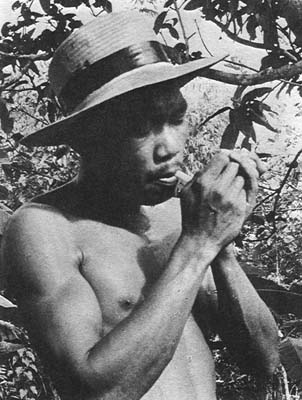

Husen, 31, a Javanese rice farmer and betjak driver

Karniti, 19, his wife

In Part One

Husen’s father, 61

Husen’s mother, 55

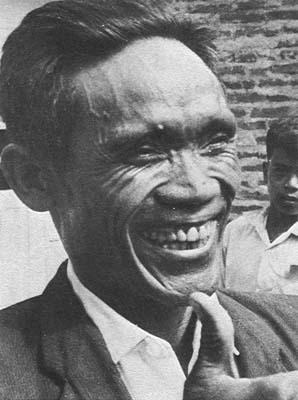

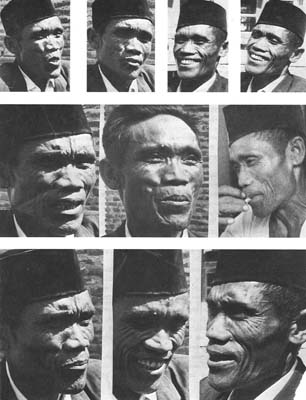

Lojo, 65, a popular comedian

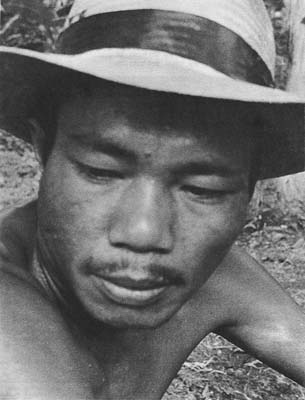

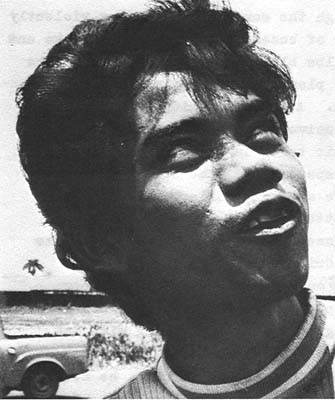

Abu, 22, a village extension worker

In Part Two

Lieutenant General Ali Sadikin

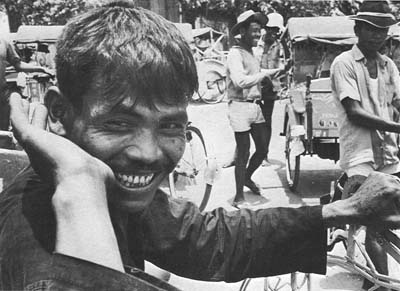

Djuned, 27, a villager-betjak man

Tjasidi, 23, a villager-betjak man

Tjasta, 31, a villager-betjak man

God’s Will Be Done

It is twilight. A misty drizzle, the last of the afternoon’s thunderstorm is gently drifting down on the newly lighted kerosene lamps of the street stalls and lying in soft, glistening wetness on the pavement, the canvas hoods of the line of betjaks and the lean, hard-muscled shoulders of their drivers. The streets are covered with puddles, and although a bright rosy glow appears on the angled glass surfaces of the Hotel Indonesia’s fourteenth floor, as a break in the clouds, the end of the storm and the onrush of the tropical night come all at once. The entire circle seems to be a landscape of flowing, falling water. It pours down the rusted steel girders of the twenty-nine story skeletal skyscraper across Djalan Thamrin, washes down the austere facades of the British and German embassies, surges through the canals and splashes violently from the gathering evening traffic of buses, motor scooters, tracks and cars. As thousands of electric bulbs blink on like fireflies in the night everything seems wet: ferns, plants, trees, palms, skyscrapers, shanties and people drip with rain. A fresh, warming breeze appears – the rain relents. The day’s oppressive heat and gasoline fumes have been washed away and the evening air takes on a gentle fragrance, one gets a whiff of frangipani or perhaps jasmine, the spicy smells of food from the street stalls and the sweet, peculiarly Indonesian odor of clove-spiced kretek cigarettes.

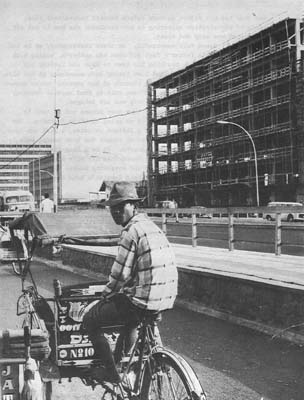

The betjak driver, Husen, is quite wet and looks like a phantom; he is seated under the dripping hood on the betjak’s upholstered seat, which is mounted on a bicycle base. The other drivers, now that the rain has stopped, move about, bright brown faces beaming, white teeth gleaming, laughing and joking with one another. Husen sits almost bent double. Bareheaded, barelegged and barefooted, his shorts and shirt torn and soaked through, he never makes a move. If the heavens again opened up with a torrent of water it seems as if he would not stir to find a better shelter. He is, no doubt, plunged in deep thought. If you were snatched from your rice fields and gardens, from your usual green surroundings so beautiful, mysterious and intimate men have made nature their god, and thrown into this confusion of monstrous lights, unceasing-noise and hurrying people, you too would find it difficult not to think.

Husen and his betjak have not moved from their place in the line at the hotel for a long while. He pedaled up before Moslem evening prayers, and, up to now, not a fare. The evening mist is descending over the city and the pale colored lights strung around the obelisk in Welcome Circle grow brighter. The drumbeat of a dance band drifts down from a rooftop restaurant. A shiny, black car with a diplomatic flag glides past the betjak men into the entranceway.

“Betjak!” suddenly hears Husen. “Betjak!”

He sits up but several drivers, as soon as they saw guests coming from the hotel, have left the line and are pashing their betjaks toward them, smiling eagerly.

“Hello, mister, where are you going?”

“We need two this evening, Tjasta,” calls a tall European, in evening clothes.

“I can take both, tuan.”

“Maybe you can, sport. But we want to be comfortable. Where’s your friend?”

Another driver is summoned and the two betjaks move off with their passengers. Husen pulls from under the seat a crumpled packet of kretek cigarettes and crouches over to light one. He inhales deeply, retaining the clove-scented smoke in the hollow of his chest and then blowing it through his nostrils, slowly, as if to draw its warmth to his wet body.

Along the sidewalk a vendor approaches knocking a hollow bamboo stick on a piece of wood to make a pleasant ringing sound. He balances two heavy tin cans suspended from a bamboo pole and moves with short, quick dance steps, swinging one arm lustily and using the other to keep his shoulder pole in place. Near Husen’s betjak, he sets his burden on the sidewalk, opens the can, perches on a stool and spreads out a food counter of shredded cabbage, tomatoes, pieces of chicken, warm boiled rice, jars of spices, noodles and white china bowls. Several betjak drivers squat on their haunches around this improvised restaurant for their evening meal and the smell of soup hangs pungent in the air; it seems to Husen as if he can taste it. His stomach rumbles with hunger; he has had nothing to eat since morning and puffs more furiously on his kretek.

All around him there is activity now. A steady flow of people walk on the sidewalk past the betjak stand, going in and out of the hotel: orchestra players, waiters, security men, guests.

A European youth with long hair, beard, sandals and a rucksack strolls by. “Hello, mister, where are you going?” comes a chorus of deep-throated voices. “Just for a walk,” mutters the hippie, moving quickly on.

Most of the drivers put down their hoods and climb into their betjaks to rest and talk as they wait for fares. Husen listens idly to snatches of conversation.

“There was a fight at Djakarta Fair last night. One drew a pistol. The other used a knife.”

“Last night my passenger was an American who was drunk. He made a lot of trouble but I don’t care.”

Two men are discussing a football match and Husen calls to them, “How is the score?”

“I don’t know. But at half-time it was two to two.”

“Those Koreans are unfair. They kicked our players.”

A young girl approaches from the hotel and Tjasidi, a tall, curly-haired youth, calls loudly, “This one must be for me.”

“No. She doesn’t belong to you, she’s for me,” laughs another.

The girl walks hastily past them to an older driver and negotiates a fare, as the two youths laugh. “Hello, where are you going?” Tjasidi calls after her. “Maybe going to restaurant, bar, Djakarta Fair?”

There is a commotion at the curb as two fat Dutch ladies arrive in two betjaks and disagree on the price. “All, all!” one cries vehemently, answered by the drivers’ pleas of “More, ma’am.” As other drivers gather round, the ladies give some Netherlands coins to the two men and hasten into the hotel. “Three hundred rupiah,” shouts one of the drivers after them. “Because big one.”

Another girl appears and this time chooses Tjasidi’s betjak. He brushes off the cushion and with a bow says gallantly, “Please sit down.” “Thank you.” As their betjak moves off the other drivers hoot after them, “Awas, awas! Watch out, watch out! Be careful with that one, miss!”

Along the sidewalk two tall, huskily-built youths with brilliant black hair, sunglasses and tightly fitting yellow slacks, their arms entangled, approach the hotel. Husen hears one complain bitterly, “Only for money. Not for love. I’ve had over five hundred Europeans in the last six years and all they ever made was false promises.”

Husen is distracted by a man on a motorcycle who roars up to the betjak stand and shouts, “There’s robbers! Please come! Stop them!” Six or seven drivers mount their betjaks and move out on Djalan Thamrin together, in what seems to be a formidable force. Husen joins a group gathering on the sidewalk.

“Hey, what is the story?” he asks.

“I don’t know,” shrugs a cigarette vendor. “Maybe pickpocket.”

“It started from Djakarta Fair, maybe,” says a betjak man. “I heard there were two gangs fighting each other and that man who rides the motorcycle knows one of the boys and he thinks it’s robbers but he doesn’t know exactly what.”

“I heard it’s two teenage gangs fighting. They were stopping cars and robbing people.”

“Some had pistols and were firing in the air.”

“Maybe the sons of generals or army men.”

The speculation goes on. Husen sees two foreign women approaching and calls to them, “Always tired, Madam. If take betjak, not.”

“No. We want to walk.” Husen watches the two women become surrounded by vendors selling curios, bows and arrows and velvet paintings from Bandung, carved daggers, and magazines. He tells another betjak man to follow alongside them; they will soon tire of fending off the vendors.

Husen returns to his betjak and once more, as in the rain, he feels alone and surrounded by silence. With an anxious and a hurried look, he searches the hotel entrance crowds for one person who will take his betjak. But all the guests seem to be getting into cars.

“Betjak, betjak!”

Husen jumps this time and sees a soldier over his shoulder.

“Bapak [Note: father, here used in a show of respect], where are you going?”

“Only over there. To Blora.”

With a nod of assent, Husen lifts the betjak and wheels it around on its back tires, the soldier seats himself and Husen mounts his leather perch behind the passenger seat. He pedals, briskly, his knees pointing outward and his hands clasping the handles on the back of the seat; the entire chassis, passenger and all, must be rotated to steer and one needs as strong arm muscles as leg muscles. Not far down Djalan Thamrin, just past the Kartika Plaza hotel, he must dismount and starts pushing the betjak up an incline.

“Where are you going, badoh tolo kamu! You stupid fool!” is the exclamation Husen hears from the hunched figure in front of him.

“Where the devil are you going? Go under the bridge!”

A youth on a motor scooter, speeding and skidding on the wet pavement, swears at Husen; a passerby, who has run across the road and rubbed his leg against the betjak’s wet tires, looks at Husen furiously as he brushes his pants off.

“You do not know how to drive. If there’s an accident, then what? Hey, is this the right way? Do you know or not?”

“Please, Pak, once more, where are you going? Maybe I have it wrong.”

“To Blora, fool. Blora, Blora.”

They pass underneath the bridge and in the momentary darkness, feminine voices call to them.

“Hey, Husen, have no money!” “Hello, hello, Pak, where are you going?” “Hey, you like to go pooki pooki? You like come sleep my house?”

The soldier laughs. “Bantjis [Note: male homosexual prostitute who dresses in women’s clothing to attract customers and deceive foreigners]. Only the foreigners take them for women.”

Seeing his passenger in better humor, Husen moves his lips. He evidently has decided to say something but the only sound that issues is a choked sigh.

“What?” asks the soldier.

Husen twists his mouth and grins nervously from ear to ear. He is away from the hotel now and feels he must speak to someone, some stranger like this soldier. With an effort amidst his labored breathing, he says hoarsely, “I beg your pardon a thousand times, Pak, because my boy – my baby son – he is not here, that is, please lighten the burden I bear by giving me your pardon. I know I must be iklas. [Note: State of willed affectlessness, highly desired by Javanese]. It was God who took my boy away and I have no right to complain. We must bend to the will of God, mustn’t we? I mean, what could I do anyway? But you see, I beg your pardon a thousand times, Pak, but my son died this week.”

“Hmmmm! What did he die of?”

Husen leans forward, almost rising from his seat and says, “Who knows? They say fever and influenza. He was sick a week and then died…I took him to the doctor for an injection and then to the village and then he died…Inallillahi Wainna llilla hi Roziun. God’s will be done.”

The betjak hits a pothole in the road and the soldier is almost thrown out of his seat.

“Watch out! Tolol! Fool! You have not eyes!” Husen dismounts to push the betjak wheels out of the hole and back on the pavement.

“Go on, go on,” grumbles the soldier, “Hurry a bit.”

Husen straightens up again, straining his back and legs and pedals as fast as he can.

“I am sorry about your son,” the soldier mutters.

Several times Husen seems as if to speak again, but the soldier, perhaps worried he will be asked for money, has turned, squarely to the front and apparently is not disposed to listen.

At an open air restaurant in Blora the soldier motions for Husen to stop and jumps out, handing him only a ten rupiah note.

“Wah. Not enough!” Husen exclaims.

“Why not enough?”

Alarmed he has annoyed the soldier, Husen grows apologetic. “You don’t be angry with me, Pak. All right, you haven’t money, okay? I am sorry.”

Husen pedals quickly to a tea stall, seats himself in his betjak and again remains motionless, staring now and then up at the trees and stars. The road is almost empty and he starts to rise to hunt for passengers, doubles himself up and abandons himself to his grief. In less than five minutes he straightens up, holds his head up as if he felt some sharp pain and stares forward.

Why? Why? he asks himself. My little boy was not bad. He had done no wrong. He was but one year old. So clean and fair-skinned. And big and healthy with a long nose like a Dutchman’s. He didn’t deserve to die so young. Why not me instead? I want to die too. No. I must go on. For Karniti’s sake. They say in the village she has cried solidly all this week, even since I left, that she can’t sleep, can’t eat or anything. If only I can find money for the slametans. [Note: Javanese version of communal feast, symbolizing mystic and social unity] – maybe ten, twelve thousand – I can go back and take her to the dukun. [Note: Village faith healer or witch doctor or masseur]. Maybe he can give her some magic tea to drink so she can sleep. But now I must be iklas, must be iklas…He sits numb and in silence. An hour passes, and another…

Along the road, with laughter, curses and load voices, come three young men, foreign sailors in white uniforms, two of them short and stocky and one tall and thin.

“Hey, betjak! How much to Chez Mario?” calls the tall one.

Husen hurries to mount the betjak and smacks his lips. Perhaps he will earn money this night after all.

“One hundred fifty.”

“No, fifty. We don’t wanna come back.”

“Oh, no, no, not fifty, sir.” Husen twists his mouth into a smile. “Chez Mario is a long way. Two and a half kilometers from here. Where you want to go? You go to Club 69?”

One of the short sailors groans. “We went to Club 69 last night and got taken.”

“I drive you, okay, Papa-san?” The tall one was already on the betjak seat and began pedaling the machine a few yards before he found he couldn’t steer and thumped into the road bank.

“Look,” he calls, coming back. “Look, I pay only fifty. You have too much money, papa-san. You don’t give it to your wife. You go out and drink beer and see taxi-girls and get into trouble. I’ll pay you only fifty and keep you outta trouble. How’s that for a deal? I don’t want to talk about it anymore. Okay, I’ll give you seventy-five because you’re a nice man.”

“No, sir, one hundred fifty.”

“If I give you one hundred fifty I no eat today, Papa-san,” the sailor laughs. [Note: The legal exchange rate for the rupiah is 375 to a U.S. dollar; its real buying value is considerably more, especially for food].

Husen mounts the betjak seat and tells the sailors to climb in. Seventy-five rupiah is not a fair price, but he does not mind – to him it is all the same now, so long as they are passengers and he is kept busy taking them around. The sailors, jostling each other and using bad language, approach the betjak, and all three at once try to get on the seat; then begins a discussion which two shall sit back and who shall be the one to balance forward on the edge. After wrangling, laughing and abusing each other, it is at last decided that the tall man should sit forward, he being the largest.

“Now then, hurry up! To Chez Mario.”

“Oh. Chez Mario,” Husen says absently. “Very far from here, sir.”

“C’mon, boy. Are you going the whole way at this pace? We’ll never get there. You’ve been screwing too many taxi girls.”

“Ha-ha-ha-ha,” laughs Husen. “Such a…”

“We should have got his buddy for the same price,” says one of the short sailors. “This is too damn small for the three of us.”

“If Chez Mario is no good we can try the Bamboo Den. It’s just down the street.”

“Are you going to speed up or not, you lazy cotton pickin’ bastard?” calls the tall sailor, who seems impatient to get to the destination. “Is this the way to drive a betjak? Let’s see you get a little steam up. Go, go, man go. Let’s see how fast this buggy can go.”

Husen listens to the abuse, listens to the jokes, sees the people and little by little the feeling of loneliness leaves him again. The tall one goes on talking and he chokes in a coughing fit. The other two begin to talk about a certain Australian girl named Angela they met the night before at Club 69. Husen waits for a temporary silence, then asks, “What are you? What is your country? Australia? Holland?”

“America,” says the tall one.

“Don’t knock it, buddy.”

“Ha-ha-ha-ha,” Husen laughs. “Oh, America. Much money!” He pauses for a moment and then murmurs: “My son died this week…Influenza.”

“Sorry ’bout that.”

“That’s too bad, Papa-san.”

“You sure he’s just not saying that to get some money outta us,” grumbles one of the short sailors.

“Hey, betjak, are you married?” asks the other, apparently not following the conversation. “I bet you got four wives.”

“Can you have four?”

“Yah, can. If Moslem can have four.”

“How come Moslems can have four wives?”

“I don’t know, tuan. Maybe if strong, if looking for money and is okay. Okay, can have. For me, one is enough. I have only one wife…yah, ha-ha-ha-ha, that is to say, my son is dead and I am alive…instead of coming for me death took my son. But I must be iklas. You know iklas?”

“No.” The sailors were getting impatient to reach a nightclub.

“Just like I take you in my betjak. I should feel I get a good price and you should too. So that not you or me is upset in his heart. You understand? Must be iklas and that is how I mast feel about my son’s death…”

Husen begins to tell them how his son died but at this moment, one of the sailors says with relief, “Hey, here’s Club 69. Let’s stop off and see Angela.” And Husen watches them disappear through the dark entrance. Once more he is alone and surrounded by the empty street. His grief, which had abated again for a short while, returns with greater force. He searches among the crowds trying to find one friend along the way from his village who will listen to him. But the crowds hurry by without noticing him or his trouble.

At the Hotel Indonesia a state dinner is underway and police have chased the betjaks down the street. Not noticing, Husen sees a policeman by the entrance and decides to talk to him, “Pak, what time is it?” he asks.

“Past twelve. What are you standing here for? The high people will be coming out soon and all betjaks have been ordered to move on.”

Husen starts pedaling for home, a betjak shed in Pedjampongan where he has been sleeping since he took Karniti and their sick son back to the village.

About an hour later Husen is seated cross-legged on a bamboo mat in one corner of the shed. He has replaced his threadbare shirt and the five pairs of tight short pants he wears to prevent a possible hernia with a comfortable, loose sarong and sits smoking a kretek. Out of the two hundred fifty rupiah he has earned tonight – the sailors gave him one hundred fifty after all – twenty have gone for a single plate of rice with some vegetable broth. Another ten went for coffee and a fried yam and forty for a fresh packet of his favorite kretek “djinggo” cigarettes. Eighty more has gone to pay the daily fee of the betjak owner. This leaves just a hundred rupees which is a small step toward ten thousand. Well, perhaps tomorrow he will be lucky…He will write Karniti and say it may take longer than he had hoped to find the slametan money.

The bamboo shed, no better than a crude shanty, has an atap roof, earthen floor and bamboo walls. It is only twenty by fifteen feet yet the entire floor space is filled with sleeping betjak drivers, like Husen, sarong-wrapped and bare-chested, with arms and legs entangled and the bodies packed so close the air is thick, damp and suffocatingly hot. Husen listens to the sleepers, hears some of them groan or have a coughing seizure or gnash their teeth as Javanese do in their sleep and he scratches himself where a flea has bitten and regrets having returned so early.

A touseled-haired youth in one corner gets up, grunts sleepily and goes outside to make water. Husen recognizes Juned, a fellow farmer from his village and follows him into the fresh night air.

“Juned. When did you come to Djakarta?”

“Last week, Husen, but I have been sleeping at my sister’s.”

“Want a cigarette?”

“Don’t I want a cigarette! Thanks, brother.”

Husen lights it for him and the two fellow villagers sit in the doorway of the betjak shed smoking for a time in silence until Husen says, “Listen, brother, you know my son is dead…Did you hear? This week, in the village, it’s a long story.”

Husen looks to see what effect his words have and finds the other is listening as attentively as if they were back at home sitting in front of someone’s hut and talking under the stars until late in the night. With great relief, he begins. It will be a week since his son died and although he knows he must be iklas he has not been able to speak about it properly to anyone since he returned to Djakarta. One must tell it slowly and carefully: the baby had been his third child and his second to die when a year old. The only survivor was a seven-year-old son who lived with Husen’s first, now divorced wife in Djakarta and whom he rarely saw. This was to have been his and Karniti’s first child and then the boy fell ill, he suffered fever and he died. One must describe the visit to the doctor for injections, the journey to the village when these failed, going to the dukun and the details of the funeral. His wife, Karniti, remained in the village while he came back to the city to find money. One must talk about her too.

And as Husen spoke to his friend, both sensed the mystic and social bond of their village, Pilangsari, between them and it was as if the uncertainty, tension and loneliness of the city were forgotten. Both the betjak drivers were poor, both suffered the same hardships in Djakarta, but both also were bound by the same appreciation of the pervading beauty of life in their Javanese village.

Husen’s words lifted them out of their half-empty stomachs, out of the squalor at the betjak stand, out into a green misty realm of jungle, sea, river, garden, fields and sun where daily coexistence with a higher, spiritual otherworld gave life its value.

When the baby died, Husen took it from its mother’s arms and laid it in his own lap and washed it and wrapped it in fresh linen clothes and carried it to the graveyard. And he laid his little boy on his side, resting on seven stones with the head pointing north. Then he loosed the strings on the shroud and turned his son’s face so that his little pale cheek touched the earth. And then the priest stepped into the grave and said the Confession of Faith three times in the dead child’s ear.

“O, you are already living in the world of the grave. Do not forget the Confession of Faith. You will soon be visited by two messengers of God, two angels who will say, ‘O, human being, who is your God and what is your religion and who is your prophet and what is your religious lodestar and what is the direction in which you turn to pray and what has been commanded of you and who are your brothers?’ You must answer clearly and forthrightly; you most not be afraid or startled: ‘The Lord Allah is my God; Islam is my religion; Mohammad is my Prophet; the Holy Koran is my lodestar; I turn toward the Black Stone of Mecca to pray; the five daily prayers are what I have been commanded; all Moslems, men and women, are my brothers.’ O, my child, you already know that the questions of the angels do in fact exist, that life in the grave does exist, that the balancing of good and evil deeds does exist, that heaven and hell indeed do exist and that the Lord Allah will wake each individual in the grave on Judgment Day.”

A few days later a visiting American official of an international development agency who had taken Husen’s betjak in the past observed his Javanese friend was troubled and asking what the problem was and hearing the story, he sent Husen back to the village with twelve thousand rupiah. This was enough to pay for all the needed slametan ceremonies, including the last, which the Javanese believe marks the time when the body has decayed entirely to dust.

Homecoming

Many months afterward. Around nine o’clock in the evening.

Husen, along with a dozen other young men, was riding in the baggage rack atop a creaky old passenger bus on the Djakarta-Tjirebon highway. Although the wind was cold since nightfall, Husen did not mind. He would soon reach the little market town of Djatibarang and, from there could take a betjak or walk the last three kilometers to his village. Besides he enjoyed the feeling of freedom, of rushing through space and the jokes and companionship of the youths, who preferred to brave the cold and wind rather than sit in the hot, cramped interior of the bus itself. The trip had taken five hours and once outside Djakarta nature was beautiful. Everything was green, every shade of green and there were reds and yellows too. Fruits and vegetables seemed to grow to giant size this year and all the vegetation looked rich and tall. All along the two-lane highway were single-story houses, some of stone but mostly of white-painted bamboo; their bamboo picket fences seemed to stretch – broken only by the occasional roadside rice paddy – in a single line all the way back to Djakarta. The houses all had red-tile atap roofs, else they would be flooded in the almost daily downpours. They were surrounded by trees: fat, stumpy banana trees with wide, fibrous foliage; palm trees, some low, some soaring up majestically to fifty feet, clean and straight as telegraph poles with towering crowns of outstretched branches; clamps of feathery bamboo, their green trunks leaning left and right; and mimosa bushes hang with golden balls. Every so often there was a big waringin tree [Note: What is called the banyan tree in India], its trunk of great height and width as its branches reached downward to implant themselves in the earth only to take root and shoot up again as new trunks linked with the original one. To Husen, these giant trees, constantly renewing themselves and enduring for centuries, seemed to symbolize the vital essence of life.

The highway was thick with traffic: cars, buses, trucks, scooters, bicycles, betjaks. On the tailboard of one truck somebody had painted, in neat lettering, “No Time for-Love.” On others had been scrawled, less neatly but always in English, “Love,” “Revolution,” “Mr. Sly” and, curiously, “Humble Pie.” The bus driver was in a hurry and sometimes the bus would lurch as it passed another vehicle and the youths on the roof would have to grip the luggage rail tightly so as not to be thrown off. The bus knek [Note: From the Dutch knecht or manservant] or driver’s helper, who clambered on and off the roof at every stop, told Husen he had twice ridden on buses that rolled on their side; he advised him to jump upward, away from the falling side if it happened. Otherwise one might get crushed.

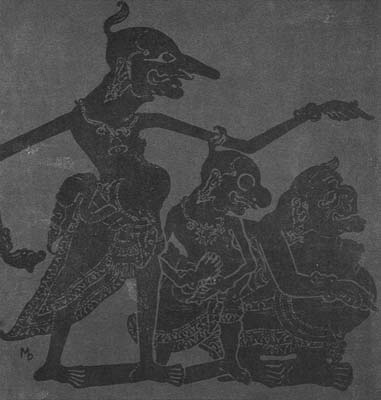

When darkness fell, the bamboo trading shacks along the highway were lit with hanging kerosene lamps, little orange glows that gave the villages an enchanted, strange air. In some villages along the highway crowds had gathered for a wajang kulit [Note: The famous Javanese shadow play] or sandiwara drama performance and the roadside would be lined with little stalls selling tea, coffee, cakes and cigarettes.

In Djatibarang, Husen shouted to the driver to stop and barely had time to scramble down the ladder before the bus was off again. He carried no luggage; the tight-fitting betjak shorts and threadbare shirt he wore in Djakarta were left behind at the betjak stand. Husen kept a toothbrush in both the city and the village and soap was a luxury. Besides he hated to be encumbered by possessions of any sort when he moved about.

Most of the shops were already closed in Djatibarang but people were still moving about and Husen walked for a time until he reached a betjak stand on the road to his village.

“Hello, Husen. Okay, use my betjak?” It was a neighbor from Pilangsari and Husen climbed into the betjak, feeling very much the Djakarta man in his maroon pullover and long trousers. “If tomorrow night you want to look at a guitarist from Tjirebon you can come on this road with me,” his friend advised.

“Okay, maybe tomorrow night if I have time. Do you like cigarette? Okay, please.”

“Thank you very much.” Few of the villagers smoked factory-made kreteks, which were considered a luxury, but rolled their own out of palm leaves. It was very dark along the road, most of the kerosene lamps in the houses were already extinguished and all around them there seemed to be only trees, fields and a star-filled sky. From somewhere came the sound of scolding birds, interfering with each other’s sleep. As they drove along, the betjak creaking in and out of the ruts and the driver breathing more heavily, Husen noticed motionless shapes seemed to be dotted around the fields, peeping out from bushes and hiding behind the trees. All seemed to have a resemblance to people and filled him with suspicions and fears.

“Okay, friend, this place has many ghosts,” he told the driver.

The other said the government had cut down many trees to widen the road; it was to be paved as a new highway linking Djakarta and Surabaja at the other end of Java, some 600 miles away, by-passing the nearby port city of Tjirebon.

Husen noticed one tree, almost jutting into the widened road, had been left standing. “Remember, is this the tree that has a ghost?”

“Yes.”

“Ah, that’s why they didn’t cut this tree. There’s the Bali Desa [Note: Village headquarters]. A lamp is on.” Husen called out, “Hoi! Hoi! Stop, stop, because I want to tell my chief I’m back.” But then the lamp he saw flickered out and they continued on to a large clump of trees across a canal. Husen was speaking in a hushed voice now.

“This bridge good or not, over the canal?”

“Oh, better over there. That one is big and good.”

“Okay, over there better. Yah, all right, stop.”

“You have small money?”

“Yah, brother, have. Djakarta money. I can pay you.”

Husen crossed the small footbridge over the canal and followed a path along a grove of banana and mango trees. Through the dimness appeared a bamboo cottage with an atap roof and shattered windows. Somewhat to one side a woeful little pond was discernible; besides which drooped some somnolent little papaya trees, barren of fruit. In the blackness of the garden behind the house Husen could hear the croaking of angry frogs. Otherwise nothing else was to be seen or heard near the house except a pale expanse of open rice paddy, resembling, in the night, the open sea.

Hardly had Husen called out, “Ma! Ma!” than there was a sound of glad voices from the house – one was a woman’s, the other two men’s voices; a bolt was pulled back, a swing-door gave a squeak and in another moment a tall, spare figure stood by Husen, holding his hand and chanting a Moslem prayer. He was bald and wore only a pair of loose black pajamas and seemed very joyful to see his son again. Husen took his father’s right hand in both of his own and bowed low.

“Please inside,” the father said, as Husen’s mother and younger brother, Tarja, rushed out. After greeting them, Husen asked. “Where is my wife?”

“In Karanggetas tonight. She went across the river to visit her parents this evening. How are you in Djakarta? Are you very well, my son?”

After hot coffee had been fetched and Husen inquired if the river boatman had already gone to sleep – he always worried about friction between his parents and Karniti – he and his father went outside to sit under the stars on a bamboo bench.

Husen mentioned he had observed that the government had left one tree uncut along the road. He knew his father always enjoyed talking about ghosts and asked him, “How many years ago, Father, about the ghosts before?”

“Oh, you were like your son is now. About ten or twelve years old.”

“Oh. Yes, I not forget. It was about 1948 or so. You want to make jokes with some children and buffalo boys.”

“Yah, firstly, I just wanted to make a joke. I saw some children coming and I said, ‘Do you want to see ghosts?’ The boys said, ‘Yes, where is it?’ ‘All right,’ I told them, ‘you must take off all your clothes and follow me. Each of you must bring a tin or bamboo and hit it to make some noise. Na-no, na-no, like that.'”

The father chuckled. “Well, when they did that one of the boys actually did seem to see a ghost. He suddenly ran away and all the other children started to follow him. But I called them back and forced them to go on. I said, ‘Trus, trus, [Note: trus, pronounced “troos,” is a common expression meaning “Let’s go,” “Hurry up,” “C’mon.”], go on, go on, don’t be afraid. Let’s go, let’s go.’ And they went on, round the village. They visited all the houses which had sick men or sick children. I gave the children a chant to frighten away all the ghosts, “Patjolang, Patjaling, Patchiak, chiak, Rakim Bismillah.’ I, myself, didn’t take off my clothes. One of the boys went into a house but came running out again and kicked me. I cried, ‘Oh, don’t.’ He said he thought one of the ghosts is hiding in my clothes. Every night they went around to the houses which had sick people. All came. It was like a demonstrasi.”

He sighed. “We had a curfew then. There were Dutch soldiers in Djatibarang.”

Husen remembered. “They had red berets. In front of my school.”

“When the boy went to kick me, I said, ‘Oh, no, no, it’s me. I’m not the ghost. Don’t, don’t. I am not ghost.’ All the boys took off their clothes. That is why they could see the ghosts. But I didn’t. Only the boys. They tried to run away but I was not afraid. Because I didn’t see the ghosts I said, ‘No, no, let’s go on.’ If I took off my clothes I would get in trouble in the village. But that’s why I couldn’t see the ghosts. But the boys describe them to me. One ghost wore a red badong or sash around his waist, nothing else. The boys said he was floating suspended over the earth and was dancing.”

“I remember. It went on very night. They said the ghosts were very tall and white. Setans.” [Note: Setans is a generic word for “ghosts” in Pilangsari]

“If the ghosts walked it was not like we walk but like the puppets do in a wajang play.” The father made a floating motion with his fingers. “The ghosts stayed for a month, every night, all night, then left and never came back. At the end of the month an old man in the village had a dream. We must serve the ghosts with tumpeng poleng, put steamed rice stacked as a pyramid and dyed white on top, Yellow in the middle and black at the base and leave it with a cigar, a piece of roasted chicken, a piece of roasted fish and incense.”

For a time there was silence. A lizard shrieked from its perch in a banana tree. “Gecko! Gecko! Gecko!” There was another sound from the blackness of the garden: “Knick, knack, knick, knack.”

“Oh, maybe a ghost,” said Husen’s mother from the doorway.

“No,” the father replied. “That is only a turtle or frog.”

“In Djatibarang a small baby sometimes dies every day,” the mother went on. “I have heard many ghosts of children calling, over there on the other side of the village where the trees are thick, many, many hear ghosts.”

“There are many also in the banana grove behind our house,” the father affirmed. “People going there at night to relieve themselves sometimes have seen the earth rising like a geyser.”

Out of the darkness several figures approached, neighbor youths who made the rounds of the village at night, sometimes playing a guitar and singing the sad, bittersweet songs of Tjirebon, telling stories or dongeng, as Javanese folk tales are called, and sleeping wherever it suited their fancy. Sometimes they would talk all night, and then swim in the Tjimanuk River before going to work in the fields. The Javanese did with remarkably little sleep. One of the arrivals was Husen’s friend, Juned, also back from Djakarta, who said, “Tell us about the ghost you met in Djakarta, ‘Sen.”

Husen chuckled with self-deprecation and pleasure as the others joined in, “Yah, Husen, trus, trus, let’s go, tell us.” He was known as the best story teller in the village and was always pleased to have an appreciative audience.

The lamplight from the doorway cast a flickering halo over the group of men and youths who huddled together, Husen joining them in squatting on the ground in a semi-circle around the feet of his father. Outside the orange halo of light the world looked impenetrable and dark. The youths were resting from a day’s hard labor and edged in closer as Husen began:

“The Phantom Passenger”

I am a betjak driver in Djakarta, oh, seven or eight years ago, maybe 1960. I am going along Djalan Palam Street in Menteng at 12:30 at night and I look under the trees in front of one house where it is very dark and see this girl. I think, “Oh, this is nice girl. What is she doing here?” And she waved to my betjak. I stopped and she got into the betjak. Oh, very nice, beautiful. And I said, “Where are you going, Miss?” She doesn’t answer but just points down the street so we go. I can smell very good perfume.

“Why, Miss, are you out so late?” I am asking her. “No taxi’s now. It is after midnight.”

But she does not speak. Now before I hear people speak that there are many setan and kutil anak [Note: A prostitute ghost] on that road, Djalan Palam, which is lined with very tall palm trees. And so I say, “Where are you going, left or right?” But she only pointed to the right, to Djalan Djawa.

“Where are you going?” I asked again and again but again she only pointed, this time to Gredja Theresia Street. She used her left hand. Then she pointed straight and we went to August Salim street and then on to Djalan Thamrin. I think maybe she want going to Sarinah Department Store. Maybe to the nightclub upstairs. Because she is very nice, this girl. But instead she pointed left down Djalan Wahid Asim, a dark place and the houses not so good and I am getting worried now so I ask in a hard voice, “Where are you going?” But she not talk. One word also, no. So we go through Tanahabang and after Tanahabang there is a highway to the market and we must go up a steep hill. There is a big bridge there and usually I must get off and push. But now I feel myself very strong. I am very happy driving, very easy. Not tired. And after Djembatan Tinggi I think, oooooh, this is very nice girl. Maybe she like with me. So I reach out to touch her shoulder and, aggggggh, there is nothing there. My hand goes right through her.

At this, Husen’s audience drew nearer, just as if they had grown apprehensive.

Oh? I can see, I can see. But I cannot touch. So the hairs on the back of my neck become stiff and I see we are passing Kober Djatipetamburan, the biggest cemetery in Djakarta. Now I hear the gong of another betjak behind me. Br-r-r-r-r-r-r-ing. Br-r-r-ring. Like that. And I turned my head a moment to look but there was no betjak there. And when I turned back again the girl had vanished. I not stop. She cannot jump down. She is just disappear.

“Wah!” I think. “This is ghost! Kuntil anak!”

And I jumped out, lifted the betjak in the air to turn it around and pedaled back to the Hotel Indonesia as fast as I can. But not speak with other people. Because it is bad luck if you have seen a kuntil anak. For one week I am very lucky. I find much money with my betjak. But after one week I am standing in front of Hotel Transaera at the railroad station and I am tell with my friends, I am talk with my friends, the other betjak drivers. And they said, “Oh, that is many times in Djakarta, many betjak drivers, find like that.”

And one betjak driver said, “Husen, if you can pull one hair from the head of a kuntil anak it is very lucky. You will get rich.”

Now I know this too but I forgot. I not think because if it was girl and not kuntil anak then she is very angry with me if I try to pull out a hair. Because if not setan or ghost but girl, okay, angry, I am afraid.

But the next time I bring girl, very nice girl, late at night, how many months again I forget, I find this girl in a scary place and it is 11:30. I am the betjak driver and this girl not speak again but only point. And I am think, “It is, sama sama [Note: The same] like before,” and I am afraid like before. And so I reached out and grabbed her hair.

“Ee-e-e-e-e-e-e-ek!” this girl screamed. She is very angry. “Why you make like that?”

“Oh, I’m sorry, sorry, sorry, sorry, sorry, Miss,” I speak.

“Why you grab me like that? I call polisi!”

“Oh, Miss, I think like Djalan Palam.” And when I told her the story she was all right again and not cry for the polisi or anything. And a very big house she have. Rich peoples. One big building.

So after that if nice girl at night, if too late and they don’t talk, I don’t reach out and grab them but just try to pull out one hair. You know the betjak driver holds his hands on the sides. So if we go fast and the girl’s hair flies out I move my hands a little and try to catch one hair. I keep trying. I think, yah, if setan, one hair will I try to get. It is very good luck and I will get rich. So when girl passenger’s hair flies, I pull out one. If she screams, I think, “Wah! This is girl.”

Husen paused and laughed uproariously.

Then I am say, “Oh, very, very sorry, Miss. Your hair is flying in the wind and catch where my hand holds the side of the betjak. But there is that good luck also. If I catch a setan’s hair I will have money. So I keep trying until now. If bring nice girl late at night.

“Go on, go on,” Husen,” his audience exclaimed when he finished.

“Yah, tell us more about you as a betjak man in Djakarta.”

“Oh, yah, it is only a routine. Although I am betjak man I never join fights or demonstrations,” Husen rose, tore off a banana leaf and brought it back to the circle to sit on, dusting off the seat of his pants. “You want history about how I am staying in Djakarta?” “Better about the man in the moon,” said Juned, who had had enough of Djakarta himself for a while. “Do you want to hear about man going to the moon?”

“Yah.” “Yah.”

“Okay, I tell you the history. The first time there are three men in a rocket. Their name is Astronaut.”

“Oh, Husen, what is the meaning of Astronaut?”

“Oh, three men inside the rocket and they are heroes. And they are all clever men. Maybe professors and so on, I don’t know. You see, the United States country is modern country. And American people, they want to try everything. Maybe these Americans they want trying going to the moon and the Mars and other things in the sky. Maybe they want sama sama with God. All the time try.”

“Did they really come to the moon?”

“Maybe. But not sure also. But what for the radio tell, if not true? If Radio Djakarta tell every night, why, if not true? Already American peoples they want to try everything in the sky. Radio Djakarta tells every night about Astronaut.”

“What is Astronaut? Not understand.”

“Ah, Astronaut is three people who want to try the moon.”

“Who is that, the three people?”

“Oh, I forgot. Gordon maybe is one. Like before you see Flash Gordon? You, see in cinema? But this Gordon is better than Flash Gordon. That’s only story in book, not sure. Because three men really go to the moon.”

His friends were puzzled. One asked, “That is, not eat, not drink, in rocket?”

“Maybe bring food in the rocket and maybe bring oxygen to the moon.”

“Oh, very far. Very far.”

“I heard on Radio Djakarta. Already inside the moon. Long time ago.”

“What is proof the men come to the moon?”

“Oh, listen, listen, brothers. Three people, the radio said, went with a big rocket and a small rocket up under.”

“In the moon is only one woman, Njitawok and cat. Because if I look from here, I see Njitawok give food to the cat.”

“No, no, no Njitawok. No the trees. No the water.” Husen began to despair of making his friends understand.

“Go on, go on, Husen,” coaxed Djuned.

“Well, after come to the moon, Astronaut jumps, but most slowly. Many dust over there and many big holes. Now I know that if a nice girl like the moon it is no good. Before people see a nice girl, they say, ‘Oh, her face is like a moon.’ But now, no, because the moon is full of too many holes.”

“That is not hot, the moon?” one of the youths asked.

“Because if from here it gives light at nighttime.”

Husen replied, “Oh, because light from sunlight. Look at a mirror. If you put it in front of a lamp you can see the light.”

“Husen, if the moon turns over, why don’t the men fall off?”

“Look here,” Husen said. He took an old pail lying in the yard and dipped it into the pond, filling it with water. Then he swung it over the heads of his friends. “If you spin, it goes to the bottom, not fall down. People are like this water, stay like this. Because there is a magnet in the center of the earth. Because go very quickly.”

“Okay, go on, Husen, trus, trus. Give as another history. About history in Djakarta.”

“Oh, yah, I have one more. I hear there is a restaurant under the ocean. Maybe from Japanese. He want to make restaurant like that.”

The youths laughed. “Oh, not restaurant under the ocean! The water go inside the restaurant and the people eat over there die.”

“No, no,” Husen said. “Very large. Maybe one hundred meters. Maybe the restaurant is made from steel. In order the big fish don’t hit the sides.”

“It’s illogical,” thought Djuned, who unlike Husen, never read newspapers. “I don’t believe. And the water, many inside. How do they push the water out?”

“Oh, you don’t believe, ‘Ed? You look in Djakarta. Many. They push out water with pumps. You can see. Maybe behind the steel they fix mirror. If already take out water, they pump out with machine. Maybe give hole from the room going to, up over the water. Okay, maybe the people who eat in that restaurant seeing fish. Very happy. You can go. Looking left and right. Very happy. In Japan.

“Husen, you ever go inside the Hotel Indonesia?” This was more familiar ground.

“It looks like a beehive.”

“The people over there not fall down? How the people’s going up so high over there?”

“You don’t know how elevator is going? Okay, I tell you.”

“Riding the Elevator”

One time an American peoples come out from Hotel Indonesia. And I say, “Hello, mister, where are you going?”

And he say, “Hey, boy, you know Tjendana Street?”

“Yah, I know.”

“Take this letter and deliver it over there.”

“With you, tuan. Better with you.”

“No. I’ll wait in my room. And you must wait for an answer to this letter. Bring the reply back to my room in the Hotel. It’s number 812.”

So I took the letter to a big house on Tjendana Street. But at the corner many soldiers are waiting because it was already seven o’clock and some big generals lived around there. I am afraid because President Suharto’s house is also on that street. My President, Pak Suharto. Very near this house where I must take the letter. I’m afraid of the soldiers and stop in front of them with my betjak. “Oh, good evening,” I tell the soldiers.

“What do you want?” says one.

“No. I only want to deliver this letter,” I said.

“Over there,” the soldier said, but he pointed away from the house where I want to be going. It is inside the barricade. So I take a round and come back and ask again.

“Hello, what is it you want, betjak man?” the soldier asks again.

“Pak,” I said, because it is a soldier, “Pak, where is this address?”

“Over there,” he says, pointing the wrong way so I take another round and come back again.

“Pak,” I say this time, “this letter is for over there. Not so far from this barricade but inside.” Wah, I think, I am very tired. Go and come. Go and come. Only pay 250.

The soldier is looking at me. “Oh, yah, it is inside. Go over there.” He lifts the gate and I take the betjak inside in front of the house. But, wah! Two big tanks are in front of the house. “Okay,” says another soldier. “Come with me.” Two Panzer tanks in front of the house, wah! “Okay, waiting, waiting you.” So I am waiting while a man inside the house is writing an answer to the letter I bring. Then he sends a new letter outside. I am come back again. Wah, I think, very difficult.

Only two hundred fifty! I must go into the Hotel and go into the elevator. I am never see an elevator before and stand there waiting. The door closes. But not go up. Wah, very difficult. I wait there some time and then two white people get into the elevator, but women. I think, okay, I go up sama sama. And they push the button and we go up. But these two women, she is out on fifth floor and I want to go to eighth floor. But I not know how. So I get out at fifth floor and am looking for the number 812 on the door. But I see the two women follow me and stand and watch me. I am wearing short betjak pants.

“Oh, I am sorry, madam. I am looking for this room.” And I show them the letter.

“Okay, come with us,” one says. “I’ll bring you to this number.” And again we are inside the elevator. The lady pushed the button but we go down instead of up. “Damn,” says the lady because somebody else has pushed the button first. Because I not understand. So we go down and then up again and this lady, she is out with me, sama sama, on eighth. I am only looking for the number, standing in front of the door with 812. The lady knocked on the door and a man came out. “Thank you,” he tells the lady. “Why have you taken such a long time?” the man says to me. He is angry. He gave me the letter at seven o’clock. Now it is ten o’clock.

I am not speak much English at that time so only can say, “Going over there, going over there with the soldiers. My President, Pak Suharto stay.” And maybe he is understand because he gave me another 100 roops. “You long time stand in front of this hotel, boy?” he asks.

“Yah, long time. But I am not understand about inside of hotel.”

Inside the hotel I not like. Very quiet. Room by room, only room. You never find anybody in a gang of peoples like outside. I want to knock on the door but am afraid of wrong number. The lady knocked for me and the number is right. But if I got wrong? Wah! Many troubles. I not go inside the hotel again.”

Husen sighed and lit a kretek. To the youths in his audience he seemed very wise and experienced and they were glad to be in the village where all was familiar.

In Djakarta you must be careful, Husen continued, if you go first time to Djakarta, better you look for betjak driver, Javanese from Tjirebon. Speak, speak, like friend. You must speak friendly, like Djakarta peoples. “Okay, let’s go. Bring me over there, Hotel Indonesia. Okay, how much?”

You must tell how much from here going over there. If the betjak driver says, “Oh, never mind, it’s up to you,” maybe he thinks you are many times in Djakarta. So is like friend. If you buy cigarette and give to him and it is a new packet, you must open first. Because all betjak drivers now understand if passenger give cigarette to you with packet already opened he not like. Because maybe dangerous. Maybe some drug like opium or morphine in the cigarette.

“So it is like that, Husen?”

“Yah. If new packet of cigarettes than you smoke first and after offer to him. And after that you and betjak driver are very friendly. You must speak, speak with betjak driver so he is not tired and he bring you very well. Speak, speak, all the time with the betjak driver.

“Good, good,” grinned Djuned. “When I go to Djakarta I try and do like you, Husen.”

“Much money over there, Husen?”

Husen chuckled. “Okay, yah, if you not like me, okay, maybe much money also.”

His father said, “I forget everything about Djakarta. It was a long time ago. I left Djatibarang by truck and came to some place…I can’t remember. It was so confusing. Cars and people going every direction.”

Husen turned serious. “If you come in Gambir Station Railway you must be careful. You don’t take truck or Austin or bus in front of Gambir. You must take betjak first and have him take you to Thamrin or Harmonie or Banteng bus station. Then you can look for bus. Have sign on front. And you can take that bus. Sometimes maybe if take bus from Gambir can get robbed. Not for sure. Maybe. You must stay with friends at first. You must stay with me if first time in Djakarta.”

“Tell as a dongeng, Husen.”

“Yah, another history.”

“Oh, Husen,” laughed Djuned. “If you have many history you, are quickly old.” Husen grinned, “You like to hear story of Koler.”

“Trus, trus!”

“Koler”

Once upon a time there was a carpenter who was many times looking for wood in the forest. Because he stayed in the forest a long time, yah, maybe ten days or two weeks. Mosquitoes came, so many, many and the carpenter – his name was Koler – said, “Wah! This is not good, to stay in the forest.” One night he became very angry with all the mosquitoes and cursed. “Damn these mosquitoes! Fuck their mother!”

At this a beautiful woman appeared, who said she was the mother of the mosquitoes and had come to fulfill Koler’s wish. But while they were fucking, she turned into a giant mosquito and flew away while Koler was still inside her.

And so the carpenter’s pipe (penis) became very long, about a hundred meters, like a fire hose, so he is called “Koler” in the Javanese language.

And Koler said, “Wah! This is very difficult. I am fucking with the mother of the mosquitoes and happy already. But now my pipe is very long.”

So he bought a sarong and wrapped his pipe round and around himself, bent over and pulled on the sarong, so no one could see his great pipe. And he said, “Now better. Because no one can see. But I am very hot. Maybe good go swimming in the river.”

Across the river was a king’s palace. And while Koler was swimming, the king’s daughter and her nurses came to the river to bathe. And the king’s daughter is also swimming, swimming in the river. Koler has also jumped in the river without his clothes and when he saw the king’s daughter his pipe got hard and went across the river to find the king’s daughter.

And she cried out to her nurses, “Oh, this thing I find in the water. This is very happy. What is this?” And she told many people, “In the river, I don’t know what is this. I don’t know but is very happy.” And the next day she again played in the river as Koler was swimming on the other side.

After some days all the people in the court knew the king’s daughter was going to have a baby although she has no husband. And soon the baby is already big and can walk. The king’s daughter is beloved by all even if she is not a virgin and has a son. Many young men fall in love with her. And the king gets confused because too many nobles from other countries want to marry his daughter.

So the king has a contest for many, many peoples and he tells them, “Whoever brings food for the baby and the baby likes it, that man is its father.”

And the people, so many, bring food, like apples, like mangos, like good things, motor car, Honda, Toyota, if this year. Many, many rich peoples come because the king’s daughter is very nice. But the baby doesn’t like any of the food or presents.

Koler hears about the contest. But he cannot go anywhere. He only sits with his sarong wrapped all around him to cover his great pipe. But he hears more and more about the contest and finally thinks, “Ah, it is time for me.”

Because Koler is a poor carpenter he has nothing to give the baby. So he makes a kind of food, leftovers from pounded paddy, with gar, water and salt and puts this, called duk, in a piece of banana leaf and presses it with a brick and roasts it on the fire.

And Koler only brings this because he is a poor, poor man. He cannot walk very well, like this…

To everyone’s merriment, Husen rose and, doubled over, waddled around like poor Koler in his sarong and predicament. Husen chuckled, “Poor Koler.”

And he gives the duk to the baby and the baby eats it and likes that food. So all the people are looking at Koler and they applaud when the baby eats. “But, oh, the daughter of the king will marry with this poor man,” they say and the king is ashamed and he gives black instructions. He says that whoever can kidnap Koler and drop him in the sea will be rewarded. And the king gives money, one million roops, to whoever will kidnap Koler and he says whoever succeeds can marry his daughter.

And one evil man puts Koler inside a drum and drops it into the ocean and Koler is riding the waves of the ocean for two years. You see, these ancient people can go without eating and drinking for two years. And Koler goes to the middle of the ocean but the wind carries him back again after two years. One day the drum is swept onto the sand and a very old man, walking along the ocean, found it and opened it. “Oh, what is inside this drum?” he said.

And inside the drum was Koler and Koler stepped out and his pipe is short again and he looks a very noble prince.

“Oh, very good,” said the old man. “You stay with me.” Because Koler is now very nice. The old man stayed in a hut near the ocean and Koler told the old man all the story.

But now the king’s daughter is already married to the man who threw Koler into the ocean. At that time, the kingdom is attacked by an epidemic and many people die. Many ghosts are there also. Now Vijayakushuma as Koler is now called, since he is nice, heard that in the kingdom there is an epidemic and diseases. And the king’s son-in-law has vanished. And Koler learns about it and comes to the kingdom.

“I can help you, about this situation,” Koler tells the king, “which was created by your son-in-law because he is really not a man but an evil spirit.”

At this the little boy is coming and he says, “Hello, papa.” He recognizes Koler who is now Vijayakushuma. And the daughter of the king was surprised that Koler is back to normal and is a noble young man.

And Vijayakushuma said, “Tonight I will look for the ghost and destroy him.” And in the night Vijayakushuma went out and fought with the ghost and in the morning he told the kingdom, “Now already I have killed that ghost and lady, that was not your husband but a ghost. Your husband is me and this is my son. You know how I made this boy? If you want to know how I made this boy, remember swimming in the river? Were you happy or not? Before my pipe was one hundred meters but once you married the ghost and I am in the drum at sea for two years, my pipe goes back to normal.” So Koler and the king’s daughter lived happily ever after. [Note: Needless to say, it is much better to hear Husen tell a dongeng orally]

“Hey, Husen, now monkey and turtle!”

“Okay,” Husen chuckled. “You not tired?”

“Monkey and Turtle”

This turtle have plenty of banana trees. And from the ground the ripe bananas are too high to reach. And the turtle is confused because he cannot climb the trees. He can only stay under the trees. He wants to take the fruit of the bananas but cannot reach it. Too high.

Along comes a monkey, walking by the turtle. And the monkey looked at the turtle, who stayed under the tree and the monkey said, “Why you stay over there, Turtle?”

The turtle answered, “Monkey, can you help me get these bananas down and give me.”

The monkey said, “All right, I want to pick the bananas.” And the monkey climbed the tree and picked the bananas but the monkey didn’t bring down. He only sat there, eating them.

And the turtle said, “Where is Monkey?”

The monkey said, “Here. Awas. Be careful.” Instead of dropping bananas the monkey answered the call of nature.

The turtle again, “Where is?”

“Over there, over there. Black one.”

“Oh,” said the turtle. “You cheated me. This is not bananas. Only this is your droppings,” and the turtle ran to the river.

One day the monkey was swimming in the river but he is very cold and wet. And he comes up on the sand and he wants to find the turtle but he doesn’t see. Instead he finds a djengkok, a footstool with a carved back and a knob for carrying, and he sits down. “Yah,” the monkey says. “Oh, better I sit on this thing.” And he sat down. And he called to the turtle, “Turtle. Turtle.” The turtle said, “Tinul, tinul” in his high squeaky voice. “Yes, Monkey?”

And the monkey said, “Where is Brother Turtle?” He looks around but cannot see the turtle. And the monkey calls once more, “Turtle!”

“Tinul, tinul,” comes the answer.

Here the audience laughed at Husen’s high-pitched turtle’s voice.

And the monkey said, “Aw, goddam, shaddup, fucking, bloody, this is, my pipe has answered.” Yah, the monkey thinks his pipe has answered because he doesn’t know that he is sitting on turtle. And the monkey runs and takes a stone and bangs it down on his pipe. “Agh-gh-gh-gh!” goes the monkey and he loses his senses.

And the turtle runs away and comes back and says, “What happened to you, Monkey?”

“Aw,” the monkey said, “I am lost consciousness. Because I just hit my pipe. Why? Because I took the stone and banged it down on it.”

And the turtle said, “Oh, it was not your pipe that answered. I am is under you. You sit on my shell. You call me and I am answer. Tinul, tinul. And why you took your pipe for me?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Because I am looking to everywhere, looking for you and not find, not see you, and I am angry. And I took a stone.”

“Yes. But you are an animal. I am an animal. So you don’t lie to your fellow animals. Are you not forget before? I tell you to give me bananas but you are answer the call of nature. So now you get your turn.”

“Oh, yes.”

“That is monkey,” said Husen. “Finish,” and he doubled up with laughter. “You understand? The turtle ran away, when the monkey cries he hit his pipe. That is ‘fraid and come back and find.”

“More, more, Husen.” The youths now were beginning to stretch out, leaning against one another with their sarongs pulled over their shoulders against the cool night air.

“You want more? Okay, one or two maybe short ones and then better we go sleep. Hmmmm. You know how Tangkuban Prau Mountain got its name?”

“Tangkuban Prau Mountain”

Once upon a time one woman have a son. But this boy is naughty. And the mother make of the food and the boy said, “C’mon, Ma, give me food. You make quickly. Give me food. Because I am hungry.”

And the mother is angry with this boy because this boy is very, very naughty. He is impatient to wait. And his mother took a tjantongor wooden scoop, and she hit him in the middle of the forehead and blood came out and he ran away.

And he went to the forest and lived with setans and ghosts and giants for many years. And because not long time coming to the village and one day this boy want going to the village and he went. In the village the boy saw a beautiful woman who was very, very nice. So he love with her. And the woman also looking that boy, okay, love him also. So sama sama love. And that is about loving, already long time. But not like fucking – fucking, no. Only loving. That is, he wants to marry her first. But because the boy has so many fleas in his hair he says to the woman, “Come here, lady. Look for fleas in my hair.” The woman saw the scar on his scalp and she knows it is her son. She think, “Oh, that is my boy” and she is surprised and ashamed because she is love with him. Because she is sure it is her son. And the woman said with the boy, “You are my son.”

But the boy is not certain she is his mother. He said, “No, no, you are not my mother. I am love with you.”

“I am not forget. You have scar on your head.”

But the boy is not sure. The boy doesn’t believe her story.

The mother said, “All right. I like to marry you but only you must first make a boat and finish it in one night.”

And the boy said, “All right.” But the woman knows he cannot make a boat in one night.

The boy, he ran into the forest to seek help from ghosts, setan, giants and so on. The boy makes the boat. After midnight he wants to finish. But the woman came to see if he had built the boat. The mother saw him and was surprised he had almost finished it.

And she quickly threw up her slendang or red shawl, which looked like the sunrise and the ghosts, setans and the boy’s friends, he think it is already morning and ran away. And the boy is very angry because he knows he cannot finish in time and will never marry the woman and in his fury he kicked the boat and it fell over, on its side and now is the Tangkuban Prau Mountain.

“Now one last story,” said Husen. “The name of this one is “The Son is a Lazy Boy.”

“The Son is a Lazy Boy”

One Masir or King in Egypt has a daughter and all the men in the country want to marry her. People from twenty-five countries come. It is only history.

Husen paused and laughed.

Because so many countries come to that King he notifies nobles of twenty-five countries and says, “Whosoever is the bravest fighter can marry my daughter.”

And war breaks out between the twenty-five countries and two end up on top. Neither can defeat the other and it presents the King with a problem. So he decides to hold a second contest. For the King sees both countries are strong. And he says, “If you show adji penrawa, or telepathic powers, you can marry my daughter.”

The King has a servant who listens to what the King tells the two other rulers about the contest and the servant says, “All right, I am adji penrawa.” Neither the two other rulers possess these powers so they leave.

The servant asks the King for time. “Give me seven days.” And the King asks the servant, “You really possess such powers?”

“Yah, I do. Give me time. Waiting for seven days.”

And the servant ran away. Looking for different fruits. Mangos, bananas, oranges. And he went to the forest and dug a hole and hid the fruit in several places.

The servant, after seven days, he said to the King, “All right, Your Majesty, I am ready.”

“Oh, you are ready. You want to try with me? Okay, let’s go to the forest,” said the King.

They left the palace and went to the forest and every kilometer a fruit was buried. The King and all his ministers and the servant leading the way. And the servant said, “Stop here. Because okay already.” And he looked in the earth. The servant said, “Oh, here is mango. All the King’s ministers want to test me, all right.”

He took a patjul, or hoe, and dug up the mangos. All the people applauded and expressed their wonder. He went on and found a fruit every kilometer until they reached the forest.

So now the servant can marry the King’s daughter. He is very lazy but he is clever and already married with the King’s daughter so now the family is very happy.

But one day the King wants some more fruit from the forest. And he told his son-in-law, “Oh, can you find the fruit of Ketileng in the forest?”

“Oh, father, I am very tired to search for fruit in the forest again. But, okay, I will do you. You bring a sack and we’ll go now.”

And they went together into the forest. And after they entered the trees were very high and there were many red ants.

The King said to his son-in-law, “You can climb trees over there.”

“Oh, I am sorry, Father. I am sick in the head, maybe influenza. Better you climb, you climb the tree and I’ll gather the fruit and put it into the sack.”

The King agreed and climbed the tree and the son-in-law gathered the fruit and put in the sack.

After half an hour, the King said, “Hey, son, already or not?” The son-in-law, who had crawled inside the sack to sleep, looked up at the King but said nothing. The King called down again, “Son-in-law, ready or not?” The King said to himself, “Goddam, he went home already.” The King climbed down and saw the sack already full and thinks it is full of fruit. And the King carries the sack back to his palace. After he has returned, the King asked his daughter, “Daughter, your husband, has he already come?”

“I don’t know, father. He hasn’t come yet.”

“Where is your husband?” asks the King.

“Here I am, father,” says the son-in-law in the sack.

“Goddam, shaddup.” [Note: Husen’s version of “shut up.”] The King is very angry to have carried his son-in-law all the way back. “Tomorrow I get revenge,” he thinks.

And the next day the King told his son, “All right, we shall return to the forest and look for fruit like yesterday.”

And the son-in-law agreed. And after they entered the forest, the King said, “This time you climb the tree.”

“All right. Because today I am not sick.”

And the son-in-law very quickly climbed the tree and picked fruit because he was lazy but clever. And the son-in-law called to the King, “Father? Already?”

The King was not yet inside the sack. “No, not yet. Wait a minute.” So the son-in-law pretended not to look, only pick fruit. And he called again, Father, father.” But no answer because the King was already inside the sack.

The son-in-law took a stick and threw it down on the sack. And he heard a groan.

“Oh, I’ll climb down because the sack is already full. The King has perhaps already returned home,” the son-in-law said in a loud voice. Then he said, “Oh, I’m tired already. I can’t carry the sack.” And he dragged it over the ground. Sometimes he stumbled over the way and bumped the sack against stones and trees. From inside the sack came groans and moans. The son-in-law heard but said to himself, “Never mind.” Soon he came to a river. “Oh, this fruit is too dry,” he said and he dropped the sack into the water. The sack made a gargling sound. After the river, the son-in-law carried the sack home on his shoulder. And he called the King’s wife, Mother, mother, my father come or not?”

“I don’t know. Where is the King? Not yet coming,” she said.

And the son-in-law dropped the sack on the ground. Thump! “Wah! Aduh, aduh!” cried the King. “Here I am in the sack!”

“Oh, father, father, oh, I’m sorry, I didn’t know it was you in the sack,” and the son-in-law ran alongside as they carried the King to his doctors.

And when he recovered the King told his daughter, “Daughter, your husband must go to the rice field because it is not hoed yet.” And the daughter told the son-in-law, “Better you go work in the rice field.”

And the son-in-law took a patjul or hoe and went to the rice field. But when he got there he didn’t work but looked for snails. As soon as he found one that was empty he blew into the shell.

And the King became angry and cursed the son-in-law. “All right, we’ll go to the rice field.” And in his fury he went beating a drum, and shouting…”Shaddup, bloody, goddam.” And workers in the rice fields, seeing the son-in-law blowing his shell and the King approaching with his drum said, “Oh, see how happy they are; the King and his son-in-law are dancing.”

As Husen finished speaking the sky was already beginning to lighten in the east, the air seemed warm and fragrant and there was a scent of green grass wet with dew. His father had gone inside to say his morning prayers and most of the youths had drooping eyelids and nodding heads.

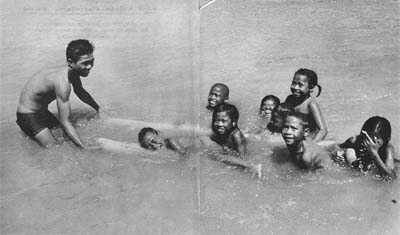

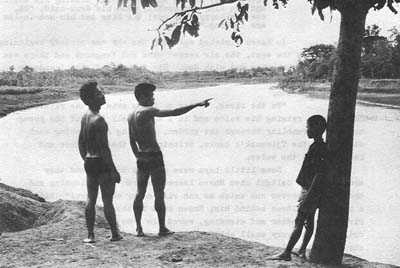

“To the river, better go for a swim in the river,” Husen said, raising his voice and in a moment, all four of the young men were scrambling through the garden, jostling and pushing each other down the Tjimanuk’s banks, stripping off their clothes and leaping into the water.

Some little boys were already bathing and they squealed with delight when Husen leaped toward them slashing and shouting, “Whoever can catch me can ride on my shoulders!” With a bevy of children behind him, Husen swam to the middle of the river to a sandbar and standing, waved his arms like a giant to frighten some very small children on the opposite bank. They shrieked with alarm and ran back to their mother who was gathering water in two cooking pots.

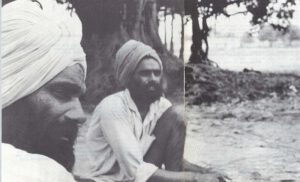

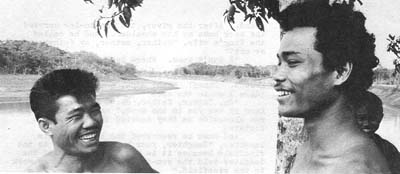

Husen and Juned.

At the Tjimanuk River

“Hey, where you come from?” called a tiny little boy.

Husen shouted back in a low, gruff giant’s voice, “I haven’t village. Can I sleep in your house?”

“No, no,” the children all shouted back. “We’re afraid you’re a tjulik (a bewitched man who decapitates little boys) or a giant!”

“Oh, if I cannot sleep in your house I will bring you to the center of the river where it’s deep.”

“Please,” the tiny boy dared him. “Come on,” the others shouted.

Husen dove underwater and the children shrieked again and ran behind their mother, clutching at her sarong. He surfaced closer to them and standing, called once more, “Awas! Watch out! I’ll carry you away to my village.”

“I’m not afraid,” retorted the tiny boy, adding as if proof of his courage, “I go with my mother to the market in Djatibarang.”

Husen dove again and this time emerged out of the water with a great leap and splash sending all the children running past their mother and up the riverbank. “Hai! Hai!” he called, laughing and then turned back to join his friends, who were already drying off again.

The sun now made its appearance on the treetops of the opposite bank and in the blue distance Husen could see the faint outlines of the sacred volcano, Mount Tjiremai, fifty miles away. As he watched a broad streak of yellow light slipped through the banana trees, glittered across the river water, rose up to touch the bank on his side, and suddenly the entire green landscape cast aside the grayness of dawn and sparkled with dew. His friends hurried home for their morning tea and something made Husen look sharply up the bank to the pathway above.

His wife, Karniti, was waiting there. “When did you come?” she asked.

“Last night. You were across the river.”

“Yes. I’m sorry. I took my mother some tea and sugar.”

“You don’t stay there, Kar.”

“I wanted to see my parents, Husen.” She paused. Although nineteen, Karniti looked even younger; with her delicate features and gentle, bell-like voice, she seemed almost a child.

“I was watching you with that little boy, Husen. That’s how our son would have been.”

“Kar, you don’t speak like that.”

“One of your mother’s kittens died yesterday. It was sick and lying by the fire. I looked to see if it was breathing and it was. But I looked again a few minutes later and it was dead already.”

“When?”

“Last evening. I was making food and all the kittens came and I looked and there were only three.”

“If it was already dead its mother would come and protect its body.”

“Yes,” Karniti turned her face away and looked into the distance, far down the river. “You maybe have another girl again?”

Husen sighed. “No, I got here late yesterday. I had to wait a long time for a bus and we sat up all night telling stories. Ask Djuned. So I am only sitting in front of the house, speaking with my friends there. No. I haven’t another girl. Why, every day in Djakarta I am only going to drive the betjak and finish and go home. I never look at anyone else. Why you think always I am having another girl?”

Karniti was facing him now and Husen could see she had tears in her eyes. “Oh, Husen, I want to sell something in the village. I want something to do.”

“Why you not wanting to go to Djakarta with me? I must go there to make money. Now we have a better room there too.”

Karniti didn’t answer.

“Okay, what do you want to sell?”

Her face brightened and she spoke as if she had had the words on her mind for some time. “I would like a small warung or shop by the street to sell cigarettes and ice and food.”

Husen could think of nothing to say for a minute. Then he broke the silence. “Better you going to Djakarta.”

But she had turned away again.

“Okay, Kar, waiting,” Husen said gently. “Maybe I’ll have money next time.”

Karniti took a few steps away from him and leaned against the trunk of a low palm tree. “In Djakarta, I have nothing to do. I’m getting older, Husen. Perhaps I could make my life better. I want to take a new step, to build a new life.”

“I know, Kar. I know.”