A Play in Eleven Scenes

Ludhiana, Punjab

April 8, 1970

Home is the place where

When you go there

They have to take you in

— From Robert Frost’s “Death of the Hired Man”

(Introductory note: The Punjab plain, a vast expanse of flat, fertile wheat land extending from Delhi to Peshawar, has historically borne the brunt of almost all foreign invasions of India. From the Aryans to Alexander, the Mongol hordes to the Moghuls, Punjab has been the traditional route of entry by India’s conquerors, who followed a path along what has become known as the Grand Trunk Road down onto the great, populous cities of the Gangetic Plain. A battleground throughout its five thousand year history, Punjab was also the scene of the partition holocaust of 1947, when within four months six million were uprooted and another million died in the exchange of Moslem, Hindu and Sikh populations forced by the creation of the separate states of India and Pakistan. Again, eighteen years later, Punjab’s green fields once more heard the Sikhs war cries of “Sat Sri Akal!” answered by the Moslems’ “Allah-o-Akbar!” in the twenty-two day Indo-Pakistan war of 1965. Daring the past five years, the Punjab, has become the setting for another kind of drama: spectacular changes in seeds and methods of cultivation in what has become known as the green revolution. Almost ideal conditions of climate, water resources and soil, together with new agricultural technologies, promise to turn the Punjab into one of the richest farming areas in the world within the next ten to twenty years. This agricultural revolution, which is taking place at a much faster pace than that which transformed Europe at the end of the 18th century, is also to some degree influenced by the character of the Punjabi people. Constantly uprooted in the past, they are the most ready for change in the future and the most aspiring for what, for want of a better word, can be called the western way of living. And especially among the Sikhs, there is a profound affirmation of life that sharply contrasts with the life-negation aspects of the Hindu religion in most of India. Throughout the Punjab today, whether among the Moslems in West Pakistan, the Hindu Jats of India’s Haryana state or the Sikhs in what remains of the old Punjab proper, the green revolution is everywhere in evidence: the new Mexican dwarf wheat varieties are universally grown, tube wells dot the landscape, every village has several tractors and land values are spiraling. A study of a representative Punjab village and farm family will follow later this spring, after I complete a third month of observation daring the harvest season. In the following vignette, Charan, the farmer who has been my principal subject of study the past two months, appears only briefly. Instead, this glimpse into the life of a Punjabi family concerns Charan’s sister, Surgit, and her nephew, Buldev. Their household, because of its comparative poverty, the father’s history of opium addiction, the farm’s isolation on the edge of a jungle and the absence of the usual large number of servants, relations, laborers and neighbors, is not intended as a truly telling symbol of the green revolution. Indeed, it was the very adversity of their situation, as compared with the more prosperous villagers I was studying, that to me made the personalities of Surgit and Buldev emerge so strikingly, To preserve some anonymity, I have not named their village and have used only first names, Since the sketch consisted almost entirely of verbatim dialogue recorded during a short stay with the family last mouth, I have experimented by putting it in play form. The action, except for the opening scene at a tea stall, all takes place outside the family’s farmhouse and in the nearby fields. RC)

Principal Characters

SURGIT

The mother, age forty-one

FATHER

Her husband, age forty-five

BULDEV

His nephew, age eighteen

CHARAN

Her brother, age thirty-nine

PALA, KAKA, GURI AND BARA

The children, ages eighteen, fifteen, twelve and nine

WRITER

A Punjabi from New Delhi, age thirty-three

THE THORN

(scene one)

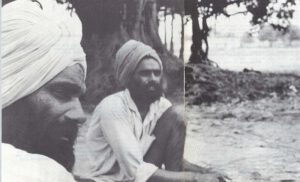

A tea stall on the side of a country road,

consisting of a thatched lean-to for shade,

a clay oven, a shelf with glasses and cups,

a pail for rinsing them, a display of cheap

cigarettes and cheroots and two benches

where a fat Hindu lala or businessman and

several whiskered and turbaned Sikh farmers

are sitting, drinking tea. Behind is a

landscape of green wheat fields, broken

now and then by a tree or a cement tube

well house.

LALA

(To the Sikh farmers, as an old white-bearded man approaches) Provide some space for the old grandfather to sit.

OLD MAN

(Munching on an orange) Lalaji, I’m better off standing. I can take care of myself. You are making me an old grandpa. Better you rest yourself. Here is a piece of orange for you to moisten your dry lips.

LALA

(Rising with an air of having important business) O, tea wallah, why don’t you keep a timepiece?

TEA VENDOR

I don’t know how to read it.

LALA

It’s so simple. When the handle goes down it’s six.

TEA VENDOR

(Grinning at the farmers) O, lalaji, my handle is always down and it’s always six. It only goes up at night. (The farmers laugh and the lala moves on. There is the sound of a tractor’s exhaust put-putting offstage. The old man waves and moves toward it.)

OLD MAN

Sat Sri Akal!

The Sikh greeting; literally “God is truth.” The majority of Punjabis are Sikhs, a religion growing out of Hindu resistance to Moslem invasions which requires its adherents never to cut their beards or hair, keep it neat with a combo carry a kirpan or sword, wear soldier’s undershorts and always carry the guru’s charm, an iron bracelet, on their wrists. Sikhs historically have been the chief defenders of India as well as its most hardy farmers, outstanding athletes and nerveless taxi drivers. The characters in this sketch are all Sikhs of the Jat or land cultivating and owning caste.

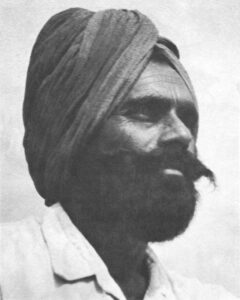

(CHARAN, a giant, black-whiskered man, dressed in a loosely wrapped yellow turban, a long white shirt with the tails hanging out and grimy grey pajamas, enters, brushing the dust of the road from his shoulders. He is accompanied by the WRITER, who, although bearded like a Sikh, has cut his hair and wears no turban. The WRITER is wearing a pink sports shirt and black well-cat slacks. Even before he lights a cigarette the farmers see that he is a city dweller.)

CHARAN

Sat Sri Akal, maharaji!

(CHARAN laughs deeply and loudly, as if he had heard a very fanny joke; his habit when greeting acquaintances away from home.)

OLD MAN

I was shouting and you didn’t hear me. I passed you on the bus.

CHARAN

We didn’t see you.

OLD MAN

You know I have married off my son.

CHARAN

Which one?

OLD MAN

(Continuing) Oh, my daughter came some time back. She was just passing through. I saw her on the bus and gave her two rupees, She said, “We are short of hay.” I said, “Don’t worry, you can have as much of mine as you like. How is lanedar?

lanedar – the head of the family or CHARAN’s father

CHARAN

You’ll soon see his face yourself. He will visit my sister soon.

OLD MAN

God is kind to us. Moreover, you, brother, are always nice to me. So I have no worries.

CHARAN

Come and drink tea with us.

OLD MAN

I have to rush home and make some ladoos (milk candy). My daughter-in-law will be giving to her parents. She must carry some sweets as they think we are starving.

CHARAN

Yes. Yes, that is always good. You must keep your foot on their neck. Then they will really respect your son. Come and have tea with us.

OLD MAN

No, I have enjoyed your gifts here. (He shakes hands with both, CHARAN and the WRITER and goes.)

(A MECHANIC in grimy overalls enters and hails CHARAN)

MECHANIC

Sat Sri Akal!

CHARAN

(Again roaring with laughter) Sat Sri Akal, young man. Are you hale and hearty? MECHANIC

How are you? Which wind blew you this way?

CHARAN

I am taking this Sardarji to the house of my sister. He is a writer from Delhi and is staying with me now. He is writing about the new seeds and wanted to see another farm. I left the cane crusher at my sister’s earlier.

MECHANIC

I know that. But you are a liar. You remember you promised to come and stay for some time and you didn’t show up. I can’t believe you in my life.

CHARAN

Don’t worry I’ll come while going back this afternoon.

MECHANIC

These are old words. I have heard from your mouth before. You never stand by your tongue. Come along right now. We have been eating. Everything is laid out for you. CHARAN

No, now we are in a hurry. I shell get myself drunk when I return. Then you can make me drink even eight bottles if you like. I won’t take a step backward.

MECHANIC

(Laughing) All right, you bastard. Let as see how you stand by your tongue. (He goes.)

(CHARAN and the WRITER sit down and order tea. Two old white-bearded men, MASTERJI, a retired schoolmaster, and HAVILDAR, a retired army havildar clerk, approach and join them as CHARAN laughs with seeming pleasure to see them.) MASTERJI and HAVILDAR

Sat Sri Akal!

CHARAN

Sat Sri Akal!

HAVILDAR

Have you come today? It is surprising to see you.

CHARAN

I have brought a writer from Delhi to stay with my sister for a few days. He is writing about agriculture and has heard young Pala is a very good farmer.

HAVILDAR

I was telling this foolish one that it is you. Now you see, Masterji, my eyesight. I can see even in the pitch dark.

MASTERJI

That is why you were shunted out of the army. They were afraid at night you might take trees for an enemy. How is lanedar’s health? Can he still walk straight with that big-tummy of his?

CHARAN

He is your age. You can say anything you like. (laughing.) But Guru (God) is kind to him. HAVILDAR

How many miles does your tractor get per gallon?

CHARAN

It can plow one and a half acres in one hour and costs you nothing. Just two liters. MASTERJI

He is also trying to get one.

CHARAN

From where?

HAVILDAR

From Delhi. From the army quota. I’ll get it very cheap. Then you’ll see me scooping around these houses, heh, heh, heh.

CHARAN

(showing impatience.) Yes, yes. We’ll talk about it later. We shall sit in the evening. (The old men shake hands and go.)

CHARAN

(Pulling their bench to the side as the vendor brings two glasses of milky tea.)

I wanted to tell you about the family since we are almost there. My sister’s husband takes opium and I want to explain the situation. (CHARAN’s voice, unlike the jovial tone of the greetings, is now serious and almost weary.) We married off our sister while we were still living in Pakistan and still rich. When the Indian government allotted lands to refugees, her husband got one near Bhadalwadh. We were in Rajasthan at the time. It was in early 1948. Her husband was already an opium eater following the example of his mother and sisters but we didn’t know it, or that he had mortgaged some of his new land until we came to visit them. Then we saw there was nothing in the house, no grains, no clothes, no fodder, literally nothing.

So we took oar sister along with as back to Rajasthan where we had rented land. Her husband came a month later. We asked him, “Why don’t you give up opium?” We kept him three months, watching him every minute and gave him nice food with milk and batter. He had pains in his joints and diarrhea but with the good rich food he gradually recovered and gave up opium. But after six months he again went back to his village and fell into bad company and started taking it again. He wouldn’t work and all his energies were spent taking opium. Five or six years went on like this.

Then in 1953, we came to our present village of Ghungrali where the government had allotted us land. When we went to visit our sister again we found her in the same condition, no grains, no utensils, no hay, no fodder. Then again we brought our sister home, along with her two sons and one daughter. The little girl was six, Pala the son four and there was a year old baby boy. My sister remained with as for four years but her husband’s condition worsened. He was mortgaging his land again to bay opium so we decided it’s better to bring him along. He had already mortgaged ten acres and we thought at least he can’t mortgage his lands further. Then for two years we gave him as much opium as he could eat. “You, enjoy yourself to the full,” we said. “You be happy with opium.” He used to take ten to twelve tolas a month. He was very happy with this arrangement. Then we played a trick and suggested to him that he make as responsible for his land. He was willing to make a mukhiarmanam or legal transfer of financial responsibility. So he wrote it down in my father’s name. Because he was happy. That village was about sixty miles from here.

One loophole was there for as. He didn’t mortgage his land through a court, only on plain paper. Then we sold out with the help of a tehsildar or land officer. Those who gave him the money tried to pull our legs but we were a match for them. We took the in-laws of the tehsildar to bring pressure on him and so he didn’t listen to those who had taken the land. So we were able to sell all of his land for sixteen thousand rupees. At that time land was very cheap. We took the money and bought twenty acres in this village. We bought a house, bullocks, implements and utensils and my father stayed here. Then gradually we started building up their farm. We took loans for a pumping set and paid it back. My father stayed there for the next six years but the husband wouldn’t mend his ways but kept taking opium. Then Pala, the oldest boy, started putting his hand on the work. And we used to arrange a laborer or sharecropper.

For the last two years Pala has taken over the whole load of work on his shoulders. His younger brother is now older too. We still go there and help them at times. Today Pala has seventeen acres of wheat, planted in the new seeds just like ours. He’s just farming like we are.

His father is still taking opium. Because his sisters eat it, he is in that company. If you send him to the flourmill to grind wheat he’ll sell some to boy opium. Sometimes we’ll give him bus fare and he’ll go on foot and buy opium. Three and a half years ago, when our niece, my sister’s oldest daughter, was at. a marriageable age, we performed her marriage. Spent every penny on it from our own pocket without any expectation of return. The groom was a relative of another sister’s husband who had left his studies after the tenth class and started farming.

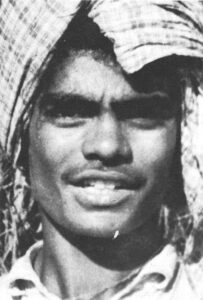

Oh, I forgot. For the past month, they have one of the father’s relatives staying with them. Buldev. He’s the son of the father’s sister who takes opium. Both Buldev’s father and mother were chronic opium eaters. The father sold all his land and became a thief. The police caught him and beat him to death in jail. When Buldev is 19 he will file a case against his father. If he can prove that the father just threw his inheritance away, he may be able, under Punjab law, to reclaim the land again. Right now he is working for my sister, but he’s a lazy, dull-headed boy.

WRITER

I shall return by bus in three or four days. Will you stay overnight?

CHARAN

Perhaps. I’ll decide when we get there.

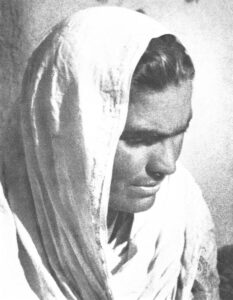

(Scene Two)

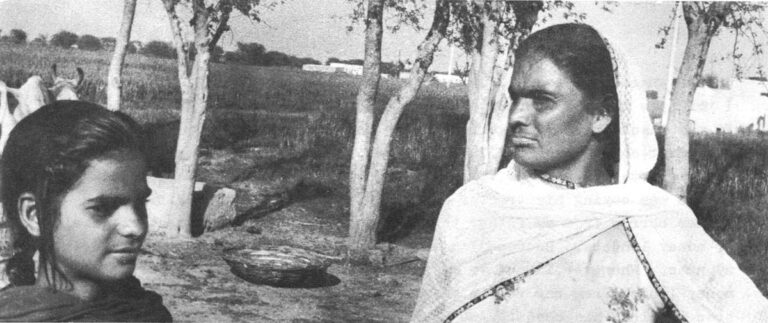

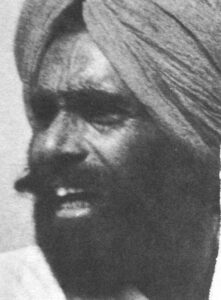

A brick hut, thatched, small, set in the midst of wheat and sugar cane fields with a jungle in the distance. On one side of the hut a makeshift cattle shed of corrugated tin sheets has been erected which houses three charpoys or string cots piled with quilts and bedding. On the other side, on an open earthen veranda, SURGIT, (Alternatively spelled, SURJIT or SURJEET)wearing an expensive but worn yellow silk salwar-kameez and a clean white cotton shawl on her head, squats before an open clay hearth, surrounded by pots and utensils, most of them silver and copper. GURI, her daughter, sits beside her. Two bullocks, three buffalo and a calf are tethered behind the hat. PALA, wearing a maroon sweater, pink turban and striped undershorts, is spreading out, to dry the chaff of crashed sugar cane. Nearby an underground fire pit has been dug over which sits an enormous iron pan for making gur or crude brown sugar. There is also an iron cane crusher, a fodder cutter, a diesel engine and a small cement pump house. On the roof of the pump house is a single light bulb, which glows when the electric current comes on. BULDEV, sits on the ground, leaning against the pump house and grimacing with pain. Beside him squats FATHER who is trying to remove a thorn from BULDEV’s foot with a needle. Both BULDEV and FATHER are dressed in ragged, grey turbans, shirts and shorts and appear grimy and poor compared with the cleaner appearance of the rest of the family. Across the doorway of the single roomed-hut hangs a garland of mango leaves, symbol of happiness and good fortune, but they are dry now and rattling in the breeze.

SURGIT

They’ll be here any minute. Masterji said he saw them having tea near the village. What are you doing?

FATHER

He has a thorn in his foot. I’m trying to dig it out.

SURGIT

(In an exasperated tone.) What now? I want him to carry fresh dirt to the cowshed and tramp it down, for a new floor. The writer from Delhi will be sleeping there. And I want to wash your clothes. They’re filthy.

FATHER

Shan’t I even finish my work?

BULDEV

It’s hurting.

FATHER

It’s nothing. The pain will go away now. I got the thorn out, I think. Wrap a rag, around it. SURGIT

Hurry, hurry. Get the dirt. You still have to go and cut fodder. (Standing up at the sound of the tractor approaching.) They’re here. (Calling toward the arrivals and smiling animatedly) Sat Sri Akal! Sat Sri Akal!

CHARAN

(Entering with R roar of laughter). Sat Sri Akal! (He puts his hand on GURI’s head but she slips away.) O, little girl, how are you? Your mother doesn’t beat you too much?

BARA

(Running up to CHARAN from the house; he limps badly) Sat Sri Akal! Mamaji!”(Uncle)

(The WRITER enters, nods in greeting to SURGIT. CHARAN points to the little boy’s limp and laughs.)

CHARAN

It is getting better now. Before the foot was quite twisted.

PALA

Sat Sri Akal! (He keeps on raking; BULDEV says nothing, but sits watching the family, a little apart and awkwardly as if unsure whether to greet CHARAN or not.)

FATHER

(Approaching CHARAN and shaking hands with him and the WRITER) Sat Sri Akal! Welcome.

CHARAN

How are you now? (Without waiting for an answer he turns away.)

FATHER

How is everybody in your house? Has the younger sister gone back to Malaysia yet? (He gets no reply.)

CHARAN

(Taking the WRITER by the arm.) Come, I’ll show you the farm.

SURGIT

Come back soon. The tea is almost ready.

CHARAN

Good. I must leave soon so as to reach home again by nightfall.

(Scene Three)

Later the same afternoon. SURGIT sits on a low stool before the outdoor hearth, preparing the evening meal. The WRITER sits nearby on the open veranda. FATHER, BULDEV, PALA and KAKA are in the fields.

SURGIT

Charan didn’t stay long. He said he was going home but if I know him he will go to his in-laws and spend a day or two drinking. I don’t know what will happen to the family. Father and Charan between them mast spent twenty rupees by evening. Ten rupees each. They are racing to see who can rain the family first. Ah, well, everybody has to hang himself. You know the saying, those who have twenty rupees in their pockets, they are kings in the Punjab and stand around and order others. Charan has changed in the last seven or eight years. I don’t understand why. He was so hardworking when he was younger. And strong. Everyone was afraid of him when he was young. Nobody would touch his arm for fear of getting a little push that was enough to make you fall to the ground.

(The WRITER rises, pulling a package of cigarettes from his pocket, indicating he will go to the fields for a moment since smoking is forbidden by the Sikh religion and those Sikhs who do smoke do so away from the house.)

No please, sit down and smoke here. We couldn’t care less. As you see, it’s a lonely place. The children’s grandma will never visit as. She says she’s got no company and no new faces to look at.

(Holding out her arms)

And she’s this fat. Another grandmother, our neighbor over there, she is really thin. She works all day long. That skinny old lady down the road. You may have seen her, brother. But the children’s grandma! She’s fat as a pig. (laughing.) This was all jungle in 1950. The minister of Nabha, Lalji, it was his land. There was a law limiting holdings to thirty acres in 1958. Nobody here has more than twenty-five. A few have only ten or fifteen but most have twenty-five acre farms. Our land is about half as fertile as Charan’s. Not such good rich soil. And much more alkaline. But it’s enough for a family. There are six tractors in our main village, two miles from here. Only two Jat families live within the village, all the rest are Harijans.* About thirty of the Harijans even own land, mostly five or six acres but four families own twenty acres apiece. It was a landlord’s village and they were tenants and could claim the land under the 1958 act. Then there are sixteen more Jat families like as living on their fields. About forty families in all live in the village. It’s not large.

WRITER

It’s beautiful here. I like living out in the fields. (SURGIT smiles)

SURGIT

Now, as you see, brother, I feel a little relieved. I had to really go through hell for years together and all the time I was praying to God, hey, Sadhe Padshah, O, Holy King, shall I ever be able to see good days again. Now He has heard my appeal and I am better off. I was only waiting for my children to grow up. Within the next few years I shall be quite free of all my burdens. I shall bring a bride for Pala and marry off this little girl. I have given the responsibility of marrying off both these children to Charan. I’ll just be sitting on a bed in the kitchen in a few more years.

(Smiling and looking out upon the fields.)

I’ll just be sitting and sleeping in the same bed. I will get up and start churning milk early in the morning so that the children can have a nice morning nap. I won’t give them any trouble. Now listen brother, God has heard my appeal and He’ll hear this also.

WRITER

Sister, I wish God will do whatever you want. But there is always a danger when the sons get married that the strange woman whom they take as a bride will make differences in the house. So it’s better if you get them a separate room before they demand one and make things worse.

SURGIT

Yes, I have a plan for that too. I’ll make two rooms on either side of this room and I’ll give one to the new couple so that they can enjoy the loneliness of their two beings. The only trouble we have now, you see, is that with only one room we don’t have enough covered places. So this year I shall make a room here where the cowshed is and I’ll take those tin sheets still further back to make a place for the cattle. I have faith in the Maharaj. He Himself will do everything for us. I have a heart as big as a lioness. One hundred people can come and stay with me. You won’t see even the slightest wrinkle on my forehead. I always treat things like that. Everyone brings his own food stamped by God. We are nobody in between. That’s why Gurur is kind to me. I have seen really bad days. Now they are over.

PALA

(Enters carrying cane from the fields.) The more you take out of this body, the nicer it becomes. After death, we can use animal skin for making shoes, but the human body doesn’t even serve that purpose.

Jat is the farming, usually land-owning caste of Sikhs, while Harijans or untouchable usually are laborers or landless sharecroppers. Although the caste system is expressly forbidden by Sikh religious teachings, it is practiced still today throughout the Punjab countryside, although, one suspects, for economic rather than philosophical reasons. The Harijans providing relatively cheap farm labor.

(Calling back to FATHER, who is carrying a light load of cane.)

Now you should work hard and get thin so that we can save some money and spend less on wood when we take you to the cremation ground.

FATHER

Son, you need not put me on a wooden pyre when I die. (To KAKA, who is behind him.

KAKA

Oh, no, Father, we will put heavy loads of sandalwood on your pyre.

FATHER

(Laughing)

Just throw me in the canal. My tiny body will be washed away.

(FATHER, PALA and KAKA return to the fields for more cane.)

SURGIT

Did you see my son-in-law while coming here?

WRITER

No, but we met your grandchild and daughter. They were coming to our village when we left with the tractor

SURGIT

Oh, yes, I understand. He must have gone with my younger sister to Delhi to see her off to Malaysia. You know he had some trouble in his head after drinking medicated liquor. Those harami, those bastards. Guru will never forgive them. His friends mixed some kind of pills with the liquor, I’ve heard. He was at a friend’s house, drinking inside all day. And when he came out into the open air, he couldn’t speak and for three days he lost his mind. He just sat on a charpoy, staring out into space. His relatives say an elderly auntie of his who is soon going to die bewitched him. I don’t believe such nonsense. I know he’s all right now. If he weren’t he would have gone with my daughter and grandchild to my father’s house. You would have seen him. He is also related to as by another marriage. We have every hold on him.

WRITER

What relationship is there?

SURGIT

The sister who lives in Malaysia. He is her husband’s brother’s son. She brought the offer for the marriage. It’s always good if we know the family.

(Her voice becomes bitter.)

Brother, you know these matchmakers. They will go to hell when they die. Sometimes they give completely wrong information about the property and land of the would-be groom. You find out afterwards he’s only a sharecropper. God will teach them a lesson when they die, those black-faced, black-tongued matchmakers. Oh, brother, I am fortunate to have good relations – whom my family knew before – for our daughter.

WRITER

When are you going to marry Pala?

SURGIT

If the Guru helps me I will do it next year. But it really depends on Charan. If he and father do this noble task with their own hands, I shall feel too happy. This year we hope to get a fine wheat crop. As it looks now. But the harvest is always in the hands of Him above as, the holy and true Maharaj with the blue umbrella. It will be according to his will. Brother, I have never used filthy language against anyone, not from my own tongue in my life.

WRITER

Why should He want to punish you? After all, you have not destroyed His field of mah. (a protein-rich pulse crop; there is a Punjabi folk saying about destroying God’s field of mah.)

SURGIT

(Laughing) Yes, brother, what to talk about, destroying mah. We have not even displeased Him once as far as my memory goes. I have always tried to be a good woman.

WRITER

Tell me about when you fled from Pakistan in 1947. Those must have been hard times.

SURGIT

(Pleased to have someone to talk to who is interested in her life.) Shall I tell you like this…. Let me see, when the trouble started…. It is so many years ago. There was a village, Kahawani, near ours. That village was a real den of Moslems. Moslems would come like an army to that village. They were always on the lookout, “When shall we attack the Sikh village.” our own. I had been married a year and had gone home to the house of my mother to have my first child. My husband stayed with his family in our village, which was in Pakistan also, Montgomery District. I remember, let’s see, the men in our village would hang big drums from the trees and they would start beating them when there was any danger. That meant the Moslems were coming. The people would cover their chests and heads with iron sheeting, like armor. The Sikh policemen would give as rifles and ammunition and said, “If you see any Moslem around your village, you can kill him.” When there was a lot of pressure from the Moslem side, some neighboring Sikh farmers and their families fled to our village. We kept dust and sand on top of their houses so if they came we could throw dust in their eyes.

That day when we saw the Moslems coming, I had had my baby, a son, nine days before. I was about eighteen and Charan was two years younger. In the days just before, when we saw Moslems pouring into their village in battalions, we stored flour, baked grams and other vegetables in case of an attack. We kept rations for ten days. People would say that on this date, August 15, Pakistan will be created. And we spent the first two weeks of August in real mental torture. If somebody would try to leave the village, the others would say, “You are a coward. You are afraid to stay in this village of two hundred families.” But as the days passed, we all began packing our possessions. There was a Moslem street in our village and one of the Moslems made a conspiracy with the outside Moslems that he would give them a signal if we started moving out.

Then we put our flour, gram and other necessary things on the bullock carts. It was noon, a very hot, sunny day. That Moslem he yelled something toward the fields. There were Moslems in the fields hiding to rush in and take their chances in looting as soon as we left the village. One of the bullock carts, the Moslems palled the bollocks away from the cart and took it and the load. The women and children were screaming and the men were chasing the bullocks. Their father caught the two bullocks but the poor fellow had to drag them on foot the whole long journey. I remember how hot and close it was. We let the cattle ran free at that time, in late morning. My father was quite rich then and we had many laborers and servants and no one in the family worked with his hands. Charan was a student in the ninth class. He was only a boy but he did not once ride in the bullock cart the whole trip. It took as twenty-seven days to reach India. My father and my uncle, Sarvan, led the family. Every one of the womenfolk were afraid. We had heard stories of what the Moslems did to Sikh women. I had my nine-day-old baby in my lap. I could not even eat, I was so afraid. Then we gathered the whole of the village at a distance of three miles. Some people were still working in the fields, plowing, and we shouted at them, “Come, we’re going!” and they dropped their plows and came with as, just as they were. All of our family had been at home that morning. We cooked double portions of roti (unleavened bread; the basic staple of the Punjab diet.) but most of as couldn’t down the food. We stayed there in the field for some time and neighboring villages also joined as. Then we made a line with the bullock carts. It was very long. There must have been thousands. On the way, more bullock carts joined as and it made a huge, long caravan. I can’t remember how many carts there were in all, but there were many, many. We would travel all day and make camp at night and the men would stand guard along the sides of the procession.

For nine days we kept on moving, until we reached Jaranwala. There was no water in the canal. Then came an airplane. It gave as signals to stop. They threw letters telling as, “Don’t move forward. You’ll be killed.” The airplane people managed to open the canal and when the water flowed in, we took baths, washed our clothes and stayed for the night. The next morning, around eight o’clock two truckloads of Dogra Hindu soldiers came. They would shout, “Sat Sri Akal!” and there were answering cries of “Sat Sri Akal!” all over the camp and everyone was happy that now we had some protection from the army. Then they told as, “You cook, you enjoy your food but we’ll march off again at three in the afternoon. Then again we moved on, but in a more disciplined way, making a long procession of bullock carts. Then, whenever it was dusk, we would halt and the Dogras told as not to leave our bullock carts, otherwise they might shoot as, thinking that we’re Moslems and they assured as of protection for the night. Three days later we reached Balokhead and they kept as waiting there for four days until the Gorkha army came to take as further. On the other side of the canal, at the bridge at Balokhead, the Gorkha soldiers appeared and they signaled as to move forward. When, as soon as we reached Ferozepur, on the Indian side of the new frontier, then the Gorkhas told us, “You are now in India and our responsibility is over. You’ll find Sikhs all around you. If you want to fight, you fight amongst yourselves but no Moslem will attack you here.” We crossed into Ferozepur at sunset. By midnight cholera broke out in the caravan. It was raining. We were twenty-five members of the family and half got cholera, most of them women and children. Mother; my sister, Nachhatar, who now lives in Malaysia; another sister, a brother eight years old, the youngest of the family; my uncle’s oldest son and four more of my cousins. So many. It was raining and we hid under the bullock carts, trying to keep ourselves dry. Throughout the night we had no medicine. We kept running out into the rain and vomiting. We knew it was cholera. In the morning, a nurse came to give as shots. All those who were not sick got them and I got a shot and Nachhatar, although we had cholera too. But the nurse wouldn’t give shots to those who were too far gone. They decided of the really sick ones, “Let them die,” for there wasn’t enough vaccine. My brother died while the shots were being given. We dug a trench and put him there to rest. I feared my baby would die also, since the cholera had dried the milk in my breasts and I could not feed him. When we were about to move forward, all of a sudden a goat came under our cart. I said to my uncle, Sarvan, “Look, Uncle, God has sent us that milking goat. Let as give the baby some milk.” My uncle tied the goat with a rope. In the meantime, the master of the goat came and demanded it back. My uncle said, “Look, brother, we have this tiny little life with as and I have tied the goat to feed him. If you want to take it back it’s your own sweet will but this is his only chance for life.” The goat’s master was a good man and he left the animal for my son. Then we moved on, putting all the sick people in the cart. My father went to fetch some onions and a bottle of country liquor to make medicine. My mother tried to fetch some medicine in the hospital in Ferozepur but thousands of people were there with cholera and they had none. But my father got some juice out of onions, some lemons and liquor and they soaked cloths in it and tried to get as to swallow it. Father tried to give some to my little brother, but it was not written in his name. He couldn’t swallow it and died. In the cart, they tried to give the girls the same medicine. When they took the cloth away from our mouths, they saw my sister, who was thirteen, and my cousin, my uncle Sarvan’s oldest son, were already dead. The caravan was already moving and we couldn’t even put them to rest. Moslem bands were still moving toward the frontier and no one dared to be separated. We just laid them in a ditch and threw some sand on them, and (Surgit’s voice breaks) in the name of God, we moved on. (She pauses and when she speaks again, her voice is hard.) By that night, we reached the town of Moga. We fed my baby with the goat’s milk. Poor little Gurmel. He was to die of measles four years later. At that time, I didn’t know if my husband was dead or alive. He didn’t know about us. At Moga, one of my cousins went blind of cholera. The next day we reached Jagraon. After we had the shots, we began to recover and in a few days we were aIl right but very tired. On the way from Moga, there was a village along the road. We asked our father, “Bapu, we want to have buttermilk.” And my father went into that village and brought buttermilk and roti back. I still remember how good it tasted. Father had a black beard then, but in a year or two it turned white almost over night, ek dum, all at once. One of my uncles had already reached Bija, our ancestral village, when he came to know we were coming. Then he came to Jagraon to receive as and we told him that so many of our family have died. From Jagraon, my uncle brought all the women and children by bus to Bija. I was very weak. When we got down from the bus at the Bija Bridge, I couldn’t walk. I just fell to the ground. My uncle had to carry me to the house. He had already occupied a Moslem house because he knew the family was coming. We women stayed in one room and the men in another. There was a Moslem woman still in the house, who had shut herself inside and said, “I won’t leave. This is mine.” We threw her out the next morning. She headed for Malerkotla, a former Moslem princely state protected by the army, but she had many ornaments and we heard she was looted on the way. We never heard what became of her.

Some of the people were good and some were bad. There was one old person who was an uncle to my father. He gave as food two times and then he took his flour and his grains to a neighbor’s and told as, “Now you have come here to eat my fortune. I won’t give you any more food. I have only enough left for myself. You have come from Pakistan empty-handed like beggars.” When we went to beg him for some flour, he snatched a copper platter from my sister and never returned it. And my sister came running home crying, “Grandfather has snatched from me the thali (copper platter) even.”

Then we borrowed some flour from some distant relatives and we bought a mound of wheat for forty rupees, although it was four times the market rate. Those rich merchants prospered on the trouble of the refugees.

There was a distant relative of ours who lived in a village the Moslems had abandoned and he invited us to come and help him harvest. They had left behind corn, chilies, sugar cane and cotton. A full rich crop. Our family moved to his village and took possession of the Moslem crop. We had a. tiny room we filled with gur from the Moslem’s sugar cane. And forty maunds of chilies and more than that of cotton and maize. So, in a way, we were again feeling ourselves in a perfect life.

Up until now my family had stayed together. But in this village my father’s two brothers asked him, “Now you are no longer rich. Now you can’t be moving around all day in white clothes with your hands in your jacket pockets. We can’t feed this battalion of chickens for you.” I have never seen my father work with his hands my whole life. That day he told his brothers, “I’ll keep my hands in my pockets like this the rest of my life. Nobody can tell me to take them out. None are yet born who can tell me what to do.”

Then my uncles said, “If you can’t work, then you and your family mast go and live separately.” So we went to my mother’s uncle, Mamaji, in Rajasthan, but Charan stayed in that village for the harvesting. When the crop was in, he and father sold out their share, put the cash in their pockets and joined as. They arrived with only one bullock, which they sold on the way, buying another when they reached Rajasthan. Then Charan farmed with Mamaji for six months, but the next crop was divided while it was still standing green in the fields. Then my mother’s father gave as a separate house and salt, spices, utensils, beds and everything we needed.

Charan alone saved the family fortune. In Rajasthan, he worked as a common laborer for daily wages for three years. Re was very hard working. Now lie seems to have withdrawn from things. It’s what we don’t understand. He’s altogether a different character now and even though he has laborers working for him he doesn0t attend to the fields.

FATHER

(Who has come up and heard SURGIT’s last words) Even I may not do heavy labor, but I’m always there to supervise my sons.

SURGIT

We think it’s his friends. There are many sorts of gentleman farmers in his village who drink and don’t attend to their fields but let their servants to do their work for them. Charan wouldn’t have finished making gur if I hadn’t sent Pala there to help him.

WRITER

Buldev was also there, helping to make gur. He is a very hard worker.

SURGIT

I heard he had a fight with Charan’s hired laborer and the man ran away. (When WRITER does not comment, she continues.) Then Charan’s a harsh-tongued person so his laborers won’t stay with him.

FATHER

He has fallen into a bad society, that’s his trouble. Charan is a good man.

(Scene Four)

The next morning. A bright sunny day. The air is full of the sound of birds, sparrows, bulbuls and bright green parrots. On the veranda, the WRITER is continuing to interview SURGIT, who is shelling peas. GURI kneels before the hearth, making wheat-cakes. PALA, FATHER, BULDEV, KAKA and BARA are grouped around a diesel engine, over by the pump house.

SURGIT

Last year when I gave away my land, eight acres on contract, I could fetch 1,600 rupees out of that. I took the money in advance. The children were not happy over it. Because the people around here started filling their ears with gossip. But I persuaded my children, “You’ll have double the crop next year with a motor and electricity. Don’t worry, my children. The people in the village are malicious. They don’t want us to progress.” So I had to persuade each member of the family that I was correct. What happened was that one day when I was passing through Chaswal village near Bhadson, I talked with the Harijans I asked to see those who were interested in having land for a year on a contract basis. Then I went and told my father and no one else and came back the next day and made the contract. We spend 1,400 rupees on the motor and fittings end two hundred rupees to meet our needs in the house. This man, havildar who lives nearby, he took a loan, about six thousand rupees, and he had to pay back much more than that. I’m complete against taking loans. I told my sons, “Whatever we buy, we’ll buy from our pocket.” They understood my language. We have applied for a small TD14 Russian tractor, which will cost us eight thousand rupees. By the time our turn comes around we shall have our own money, enough to buy one. Once I took a loan to buy that diesel engine. I took 2,500 rupees and had to pay back 3,200 rupees. But I told the moneylender not to send his peon to ask for the installments. It was insulting. “If at all you wish to convey anything to me, “I said, “you must come yourself. It’s move respectable.” Whenever he came I would ran to my father’s village. I wouldn’t have taken that loan but Charan was buying his tractor and father couldn’t spare any. I would rather borrow from my father than have to deal with government officials or moneylenders. Because I have to meet them myself. All the land is in my name. Whenever I went to my father, he would run to the office of the moneylender from the very spot where he was standing. He wouldn’t even stop to clean his shoes. And he always got some extension for me.

GURI

The roti is finished. We can eat now.

SURGIT

Come and eat.

PALA

Let as finish the work first.

SURGIT

(Proudly) Pala’s such a cruel man. He’ll let everybody starve but he won’t leave the work so easily.

PALA

Kake, go to town before eating.

SURGIT

Look, brother, he won’t even let him eat.

PALA

Go, Kake, go and fetch the electrician at once. There’s something wrong with the pump motor.

SURGIT

Let him eat first.

PALA

He can eat later. There’s always time.

SURGIT

Look, brother, he won’t even let him eat.

PAL A

Bring a screwdriver.

KAKA

Where in it?

PALA

We’ll look into this diesel engine after taking food.

SURGIT

(to the WRITER) Do you feel at home here? Pala won’t be satisfied until the motor works. Pala says lethargy hangs over him if he doesn’t work. He feels out of sorts.

(To GURI) Now you get up, get up. Go and bring the cattle into the shade. They’re burning outside.

(KAKA and BULDEV come to the veranda for lunch. KAKA sits beside the WRITER on the charpoy and SURGIT sets a small table before them. BULDEV sits on a low stool, not on the ground like a Harijan would be fed, but in a secondary position indicating that while he is a Jat, he is a landless poor relation. SURGIT serves wheat cakes, bowls of dhal or lentils and large glasses of buttermilk, giving KAKA and the WRITER plates bat giving BULDEV his portion of wheat cakes to hold in his hand.)

PALA

Kake, Oui.

SURGIT

Go run, Pala calls. (KAKA goes over to Pala, then returns to his lunch. To BULDEV) Eat, eat, eat, hurry. And relieve Pala so he can eat. He slept just in the morning hours. (BULDEV glares stonily at SURGIT bat makes no reply or apparent effort to hurry. FATHER

We must have the electrician.

SURGIT

Have food.

FATHER

Let me bring some water for you first.

SURGIT

Give the pail to me. I shall bring.

PALA

(Coming to veranda and sitting on the edge of the charpoy. SURGIT brings him food, the wheat cakes on a plate.) There is some defect in the wire but I think the motor will go now. (FATHER brings a pail of water and GURI goes to the pump and starts washing clothes. She uses almost no soap but instead beats the dirt out with a wooden pin.)

PALA

(gulping down food.) Has the motor stopped? Is the electricity gone?

GURI

No, the electricity is there. One of the wheels is running. The other has stopped.

SURGIT

(To Pala). Shall I bring more roti?

PALA

Bring.

SURGIT

How many?

PALA

One only.

SURGIT

(to GURI) Have you brought the buffalo calf to the shed?

KAKA

Does the motor go? Is it running?

PALA

Go and fetch the electrician. When he comes, the electricity goes. Give some oranges to him.

KAKA

(SURGIT offers him an orange). It’s all right. I won’t take. (He takes one and begins pealing it.)

PALA

It’s started again. But go and fetch the electrician anyway. Something’s wrong. It’s not carrying the load.

FATHER

I’m going to the crusher.

SURGIT

Shall I bring your food there?

FATHER

Yes. (To PALA) Just give me some space to sit. Push yourself a little to the side. (PALA edges over slightly and FATHER sits on the edge of the charpoy, pulling on a pair of ragged pajama bottoms to protect his bare legs from the sugar cane.) All the four nuts on the wheel went loose.

PALA

While it was running?

FATHER

Yes. Put some raas (juice from the crushed sugar cane) in the front pan. We will make gur this afternoon.

PALA

Han, ji. (Yes, sir)

SURGIT

Will those fit you?

FATHER

(They are very loose; he has lost much weight). So big?

GURI

You have only to sit at the crusher. What difference does it make?

SURGIT

Take a pair of shorts instead.

GURI

My scarf needs washing. Give me soap, Mama.

SURGIT

Put off your clothes. (To FATHER) I’ll wash them today.

FATHER

Shan’t I even eat first?

SURGIT

(Watching PALA who has returned to the engine) Now he wants to run the engine too. He may break something.

FATHER

Nothing goes wrong. Don’t worry.

SURGIT

Send Kaka to the electrician. He can also visit the tailor.

FATHER

Let them have time to go and attend to their work. They’ll go themselves. Don’t worry so much.

(PALA and BULDEV at the pump house)

PALA

Why don’t you keep the crusher clean? It’s fall of chaff. Just keep that staff apart. Now stop it. It’s jammed. You, put too much cane in. The current is quite low. We are forcing the motor when we ran it. It really doesn’t want to run. There is not enough power. So you’ve got to put less in the crusher.

FATHER

(Joining them.) Try and see if you can fix the retiming of the starter.

PALA

If it won’t work, we’ll know soon enough. Because the motor will get out. (The motor dies and the crusher stops turning.)

BULDEV

May the bastard turn to ashes. It has stopped again.

KAKA

(Joining them) The current is low.

PALA

We will fix the engine onto the crusher and do it with the diesel instead.

FATHER

(To BULDEV) Get aside. Why are you touching that? Pala is going to run it.

PALA

Bring some oil, Kake.

FATHER

(To Kaka) Well, what are you standing there for? Why can’t you pick up the oil?

KAKA

(Running to the shed and returning and giving it to FATHER) Take it.

FATHER

Why are you pashing the starter button? There is no power.

PALA

It won’t work anyway you look at it. But the diesel engine also needs some repairs. FATHER

(To KAKA, who bumps into him.) Look, look, look, see with your eyes.

PALA

(To Kaka) Are you sleeping or awake? I told you to bring the other oil. Come here a little. Just hold this tin.

(SURGIT goes to the pump with a pail of water and soap and begins to wash FATHER’s turban.)

FATHER

Give it a little starch.

SURGIT

You just wrap it around any which way.

FATHER

I would like starch. I must feel young sometimes.

SURGIT

You don’t care how your turban looks. (She uses no starch.)

PALA

We’ll try and see if it works. (Oil squirts out on the ground). Are you blind, Kake? See. You are standing with your eyes shut.

KAKA

I was just holding it. It’s you who bumped my arm.

PALA

Bring that oil to me. Let me see. The fools have brought kerosene oil instead of high speed. It doesn’t work. Oh. Kake, ran and fetch the electrician. (To BULDEV) Come and give a jerk. We’ll try to start the engine. (BULDEV begins palling the engine rope.) Slow, slow in a decent manner. Go ahead. Father, it will spray on your leg.

FATHER

It doesn’t matter.

PALA

Now tell me, are we doing the right thing? The chaff needs drying out.

FATHER

Buldev has already done it.

PALA

(To Buldev) Now move it slowly. It won’t give back a jerk. It still doesn’t run. (The exhaust begins to explode in a put-put blast, then stops.) It needs its rings changed. It’s weak at the rings. We can fix the engine to the cutting machine. (FATHER begins walking toward the house, bored with machines that won’t work.)

PALA

What should we do now?

FATHER

(Fading away) Do whatever you like.

(An impasse seems to have been reached. FATHER goes into the hut, followed by KAKA and BULDEV sits on the ground, eating sugar cane and examining his foot.)

BULDEV

My foot is beginning to hurt. I want to go in to the doctor. The pain is starting to throb. PALA

There’s no time today. We have work to do. Go tomorrow. (calling to Kaka.) Why can’t you go straight away?

FATHER

(Calling from inside hut) He’ll first take a bath, this prince, and then change into new clothes and then go, as if somebody’s waiting to engage him for his daughter.

PALA

Why can’t you without taking a bath? You can take a, bath later. We are badly stuck up. SURGIT

(To BULDEV) Haven’t you given food to the pig?

BULDEV

I thought Kaka had given. My foot is hurting. Where I stepped on a thorn yesterday. I want to go to the doctor.

SURGIT

It’s like a marriage of barbers around here. Everyone’s a gentleman and nobody will clean utensils. (Those of the barber caste clean utensils at everyone’s wedding but their own.)

PALA

Buldev, come here first. Let as give water to the cattle. Then after you feed the pig, go and start cutting fodder. (PALA starts taking the diesel engine apart.)

FATHER

(Coming oat from the house; he has stripped -to a cloth around his waist and goes to the pump to take a bath.) Why don’t you pull off the head of the engine?

PALA

It would be difficult to pat back on.

FATHER

No, don’t worry. We can fix it.

PALA

Kake, tell the electrician to bring the right kind of screw. (Losing his temper) This wrench slips. The bolt should come out but it slips. Buldev, why are you sitting there? Did you wound your foot in battle? Go water the cattle.

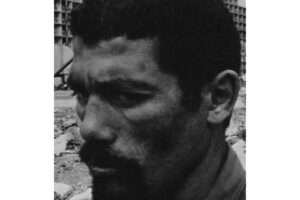

(Scene Five)

Later the same afternoon. An oat field. BULDEV is cutting the green oats with a sickle, putting the fodder into little piles as he goes along. His foot is wrapped in a dirty rag and as he works, squatting down, he drags it sideways, favoring it.

BULDEV

(Singing)

The bastard only gave me a two anna coin

After crushing my tail the whole night.

Naley de gaye duani khoti

Sari Raat gut Ragsi

Those who used to boast of death and sacrifice

See them now, running like cowards

Ran Naha ke chhapar chou nike

Safey di laat vargi

(a popular Punjabi folk song, many of the verses, like the Japanese haiku, are only two suggestive lines.)

(The WRITER and BARA, who has returned from school, approach and sit on a furrow on the edge of the oat plot.)

BULDEV

Has Gurmukh gone back to work yet?

WRITER

Who’s Gurmukh?

BULDEV

He was Charan’s hired man. We had a fight while I was there and he ran away.

WRITER

Oh, I know. No, he never came back. What happened anyway?

BULDEV

Pala and I went to work for Charan for a month. To help him make gar so we could bring the crusher back. Gurmukh, used to complain that Charan was hot tempered and hard to work for. One day we were oat in the fields, cutting fodder, Gurmukh, Pala and I, and I said, “If you’re really fed up with this job, why don’t we go and bay some sheep as a combined venture.” We were joking and having a gay time so I said, “Both of us will be grazing sheep and your wife will be milking the sheep. We could have some fun.” Gurmukh, he took it angrily and said, “Yes, and I’ll stick my penis in your sister.” I answered, “I’ll rape your mother, you bastard. Who are you abusing?” Then he muttered, “I’ll do more than rape your mother,” and he hit me over the head with a piece of sugar cane. I picked up some stones and threw at him but Pala intervened. Later Charan heard about it and asked me what happened .and I told him. He got angry because Gurmukh was only a Harijan and then he abused Gurmukh in the same language and said, “You are hurting my relations with other people. You are insulting my relations.” We were joking, we were playing and he gave an impression he was not happy with Charan anyway. Gurmukh planned to run away as soon as he had or worked off the advance money Charan had given him. One night we woke Gurmukh up about midnight and asked him, “Let’s go to the field and start cutting sugar cane so we can take the crusher to our home. We have a lot of cane and we fear we won’t finish it before the wheat harvest.” Gurmukh was a nice person but sometimes he lost his temper. He got mad that night and the next day he told Charan, “I’m not going to work here any more because your relations wake me up in the middle of the night and tell me to go to work.” Pala and Kaka do the same with me. They will Joke but when I joke back they get mad and say I am only their poor relation and I am abusing them. I want to go to the doctor tomorrow and show him my foot. It is swollen. I got a thorn in it yesterday. Once I got my finger injured while cutting fodder for the cattle and I went to a nurse who would just put something on it and wrap a little piece of cloth around it. Finally my whole arm got swollen and I had to go to the doctor. The doctor advised amputation of the arm but luckily it started healing up. (To Bara). Oh you, barber’s boy. You are sitting idle around us. Get up there end collect those small piles of oat cuttings into a big pile. Come, come. You are a nice boy. People like you. Don’t sit around. God will bless you with a beautiful bride and a couple of sons.

BARA

KAKA

(Entering from the direction of the farmyard.) If a bride brought ready-made sons to a wedding, she’d have to be as old as her mother-in-law.

BULDEV

(Grinning) No, no, young prince. She can be young. It is the groom who gets the ready-made sons eight months after marriage. My father was unlucky enough to get a couple himself. (to KAKA) Now, you go and take this bundle of oats to the house.

KAKA

We’ll take it later

MULDEV

What are you doing now? Giving milk? Go ahead, be a good man. (Grimacing with pain, BULDEV limps over to the pile of oats BARA has collected and helps KAKA wrap it in burlap sacking and lift it onto his head. BULDEV then limps back to cut more oats and KAKA and BARA go toward the house.)

WRITER

Did Gurmukh get his shirt torn in the fight? Some of the Harijans said he left because his shirt was torn away and he had no other one.

BULDEV

BULDEV

No, instead mine was torn. No, he was not happy working with Charan. No, not at all. He was just counting days so he could adjust the money he had already taken from Charan and go. You know Charan’s behavior. He will abuse anybody like anything when he is drunk and the Harijans are afraid of him. And drunk he gets every day. He would not spare even his own brother when the liquor gets into his head. Before I used to earn as a laborer, like Gurmukh, but I was a vagabond-type person. As soon as I had money I spent it for wine and meat. As soon as I had money, the people will get around me, everybody. In a village if a man has money, the poor men will send their women to him. But such women are blood and bone and promises until the money goes and then the day will come when the same women kick your ass.

You don’t know my life. When I was one year old my mother took me to the house of a man who was not my father. I’ve been earning my bread since I was ten. Nobody ever bothered about me or sent me to school or bought me clothes. They treated me as a servant or herdsman. Now I am a man and strong and sturdier than any of them and they have all started bothering about me. I want their cash and influence to get my lands back. And they want my labor. Now they know I can work like a man and carry heavier loads than any of them.

MULDEV

What are you doing now? Giving milk? Go ahead, be a good man. (Grimacing with pain, BULDEV limps over to the pile of oats BARA has collected and helps KAKA wrap it in burlap sacking and lift it onto his head. BULDEV then limps back to cut more oats and KAKA and BARA go toward the house.)

WRITER

Did Gurmukh get his shirt torn in the fight? Some of the Harijans said he left because his shirt was torn away and he had no other one.

BULDEV

No, instead mine was torn. No, he was not happy working with Charan. No, not at all. He was just counting days so he could adjust the money he had already taken from Charan and go. You know Charan’s behavior. He will abuse anybody like anything when he is drunk and the Harijans are afraid of him. And drunk he gets every day. He would not spare even his own brother when the liquor gets into his head. Before I used to earn as a laborer, like Gurmukh, but I was a vagabond-type person. As soon as I had money I spent it for wine and meat. As soon as I had money, the people will get around me, everybody. In a village if a man has money, the poor men will send their women to him. But such women are blood and bone and promises until the money goes and then the day will come when the same women kick your ass.

All my relations say that Mamaji (Mamaji means uncle. This is BULDEV’s way of addressing FATHER) will help me. I’m very doubtful about it. I don’t think he’ll help me. Inwardly, he’s with Charan’s family and Charan’s family are a bunch of crooks. They’re selfish. They will never do anything that doesn’t serve themselves. 0, Charan himself is all right when he is sober. Inside he is a good man. But it’s his old lady and the old grandfather who ran things and they’re mean. Mean, mean to the lowest. What Charan wants doesn’t matter. So he drinks.

I want to ask something of you, you are a learned man. Give me your truest advice. Don’t try to spare my feelings but speak whatever comes to your mind. It’s like this. There is a contractor, a real giant contractor, not of a liquor shop, he makes buildings. He promised to get a job for me where they’re building at the university in Ludhiana. Now I’m planning to go to him. If God permits, I’ll go soon.

(PALA joins them, gathering the oats BULDEV has cut into a large pile.)

PALA

Buldev, give me your chadra (a piece of cloth, worn sarong-like, by Punjabi farmers) to wrap these. (Instead BULDEV wraps the cloth around his waist). Help me carry these cane stalks.

BULDEV

My chadra is not for that.

PALA

O, the fine prince. He will first get himself beautifully dressed. He has been uprooted of his style of dress in our village.

BULDEV

You tell me, I am uprooted. Are you less? You are wearing pants like a gentleman and you are standing in the field. You expect me to go in rags?

PALA

(Taken aback) I don’t say anything. Do whatsoever you want. I am only suggesting that since you have to carry sugar cane now and will come back to this field, you let that dirty piece of cloth lie there. You can get it later.

(BULDEV gives him a smoldering look and limps away toward the house.)

PALA

The wheat needs water. If the electricity comes, maybe tonight we will water. I hope we can finish making the gar in the next twenty to twenty-five days. If we can get any person from the villages around here, we most start hiring them for the wheat harvest. It is very hard to find farm laborers in this area. There are no U.P. wallahs* here. You only get U.P. wallahs if there’s a rail link.

Come, I’ll show you our farm. We have two irrigation ditches. (PALA chases away a flock of doves.) Hait! Hait! They spoil the crops. Water doesn’t come up to this hillock so the wheat is in very bad shape. That marsh over there. We need to fill it in by leveling the high ground. Buldev, Kaka and I will have much to do, once the harvest is in. And tonight we must carry sugar cane back to the crusher. Everyone must pitch in if the electricity comes back on and we can use the crusher.

(Scene Six)

The farm hat again. It is sunset and flights of cawing crows pass overhead. Buldev, only a now soaking-wet chadra, is drying himself after taking a bath under the pump.

SURGIT

(Calling to him.) Now be a tiger. You have taken a bath. You look fine. Go and get the cow some water.

BULDLEV

I have just taken a bath. I’m resting. Why don’t you send one of your own children. You always treat me like someone else’s child.

SURGIT

(Furious, her voice rising) What have I done to you? Have I fired a bullet at you? I’m just asking you to do a little job because I want to milk the cow.

BULDEV

I won’t do it. I’m tired.

SURGIT

What have you conquered during the day? There were just two small bales of oats. You couldn’t finish even them.

*migrant laborers from neighboring Uttar Pradesh state

FATHER

(Calling from the house) Why can’t you wear the other shirt, Buldev? It’s cleaner. Now you have taken bath. It’s lying here. It’s clean. Now you have taken bath. You have put that old ragged thing on you again. It will be smelling all night.

SURGIT

What has come over your nephew? (Emphasis on your.) He goes ten days without hardly washing and now he has spent more than an hour taking a bath.

FATHER

Leave him be. Why do you bark at him so? His foot is hurting him. It will be all right. Everything will be all right.

(Scene Seven)

Two hours later. Darkness has fallen but it is again a bright moonlit night. The entire family and the WRITER sit on the veranda, finishing their supper. BULDEV’s foot is hurting him badly now and has swollen much larger than in the afternoon. He is huddled on the ground, alongside the pump house, nursing his pain.

FATHER

Buldev, come and have food.

BULDEV

I’m not hungry.

SURGIT

I know you are not hungry. I know that very well. Somebody has been whispering in your ears. One of the neighbors, I’ve been noting it for the last two days. You are listening to malicious gossip that we won’t feed our nephew if you don’t work. Well, you Just sit all day long on the charpoy and we’ll give you food. (Working up her anger.) But you see, you can’t expect as to touch your feet (gesture of obeisance among Sikhs and Hindus) if you don’t want to eat.

FATHER

I know what’s the matter.

SURGIT

I can’t stand this sort of attitude. You have been told wrong things by other people, Buldev, and your head has been tamed sideways.

(There is a long silence; the WRITER lights a cigarette and matters something about it being a good supper. SURGIT doesn’t respond; she is fuming with anger and seems oblivious to a guest in the house.)

Your nephew has not eaten.

FATHER

Let him not. I’ll treat him the way he deserves.

PALA

What he wants is a good beating, that’s what he wants. He will return to his senses then. SURGIT

And if he runs away? What then?

FATHER

Let him. We can’t be apologetic. It’s his fault.

SURGIT

And where would we get the money to hire someone in his place? (BULDEV, as if to avoid hearing more, rises and limps off toward the dark fields. PALA jumps up from the veranda and runs to follow him, catching up just as BULDEV enters the sugar cane field.)

PALA

Come and carry sugar cane. There is work to do.

BULDEV

I can’t carry anything. My foot really hurts now. I’m barefooted. I could get the other one cut also, then what would I do?

PALA

You’re lying. You just want to get out of work.

BULDEV

You bastard. I won’t do anything for you. You don’t realize I have a bad pain in my foot.

(PALA lunges at BULDEV. They both fall to the ground. PALA beats BULDEV until he recovers his surprise. BULDEV smacks PALA hard in the face with his fist. PALA rolls off, howling with pain. Blood is gashing from his nose. PALA runs into the dark fields. BULDEV returns to the farmyard where FATHER, SURGIT and the WRITER have rushed from the veranda to see what was happening. BULDEV is sobbing as he limps toward them. FATHER and SURGIT stand away, but the WRITER, abandoning his role of detached, silent observer, goes to BULDEV and puts his hand on his shoulder.)

BULDEV

(Sobbing and shouting at once) He was ordering me to bring canes. Why should I do that? Here I am dying with pain and no one bothers. I’m wise enough not to make a contract with you. Otherwise you would treat me worse than a slave. Pala was telling me last month that I should sign a contract. If I did with you, I’d be trapped.

WRITER

It’s his sore foot. He shouldn’t have been on it all day.

FATHER

(Angry at the WRITER’s intervention in a family matter.) No, that’s not the trouble. I know what it is. You don’t know. He had more pain yesterday. I told his to rest and he said, “I’ll go on working equally.” Today he has less pain. Today somebody in the village came and filled his ears and said, “You’ll get your leg amputated if you keep on working for them for no money like a donkey. Why do you put up with it?” It’s some neighbors. They’re down on us and take every chance they get to hurt us.

(To BULDEV) Take my bedding and sleep.

WRITER

(Unconvinced.) I shall take Buldev into the village doctor the first thing tomorrow morning. (Neither SURGIT nor FATHER replies) (BULDEV goes to FATHER’s charpoy beside the pump house and pulls a quilt over him. The WRITER takes one of his suitcases from the cowshed and props up BULDEV’s foot with it.)

WRITER

Keep it higher than the rest of your body so there’s not so much pressure of blood on it. That’s where the throbbing pain comes from. We shall take the bicycle and go to the doctor in the village first thing in the morning. (The WRITER returns to his cot in the cowshed, undresses and slips under his quilt. PALA comes out of the darkness and enters the house. The WRITER leans on one arm, listening.)

PALA

(His voice breathless.) We will tie him with ropes and teach him a lesson, the way he behaves. He must know that he cannot behave like an over clever man with our people.

SURGIT

(From inside the house) He’s in the habit of running from one place to another and we need to make him understand how things are.

FATHER

Go to sleep now. It doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter. Everything will be all right.

(Outside in the darkness, the WRITER sits up in bed and lights a cigarette. He sits there smoking for some time, the cigarette glowing in the darkness, until the voices in the hut die away and all are asleep.

(Scene Eight)

The following morning. SURGIT is cleaning up the hearth after breakfast. The WRITER and BULDEV are preparing to go to the village.

BULDEV

(Rummaging through a pile of ragged clothes he has taken down from a nail in the cowshed.) I want to go to the village and there’s no really good shirt with me.

FATHER

You can take one of mine. They’re lying there on the charpoy.

SURGIT

(Intervening) What do you think, Buldev? You have three shirts and now you want teryline. You’re copying Pala.

FATHER

‘Why do you bark so? Let him take my shirt if he likes.

SURGIT

Why not? You can give anything you like to your relation.

(To the WRITER)

Don’t give him any money, brother. He’ll buy chewing tobacco.

BULDEV

Why? Do you think I’m afraid of you. If I have to bay a small sack of chewing tobacco, I’ll buy. I’m not afraid of anybody.

SURGIT

Yes. You’ll never follow the advice of your elders. It’s in your blood.

BULDEV

Don’t abuse my blood. My blood has nothing to do with you. Just talk to me straight whenever you want to talk. You are in the habit of abusing my blood at every time. I won’t tolerate it any more. My blood was the best for you at one time and you thought it most honorable too.

SURGIT

(Wounded and afraid he will say more.) No, what is it to me? Why should I abuse your blood? After all, we won’t get poor if we spend ten paisa for your tobacco each day. (FATHER, dressed in fairly clean clothes, comes oat of the house and takes the bicycle, walking it out to the road.)

WRITER

Where’s he going?

SURGIT

He’s gone to town to find the electrician. Kaka didn’t bring him yesterday.

WRITER

But now we will have to walk. Damn, Buldev, shouldn’t be on that foot. (SURGIT does not respond and BULDEV, using a wooden staff as a crotch, begins to limp toward the road.) SURGIT

(When Buldev is oat of earshot) Brother, just take care of him. Don’t let him loose. Even if he says he has to make water. Be careful.

WRITER

Why?

SURGIT

He may run away. How can you believe in these free-eaters? How can you depend on such people? They have no house anywhere in the world. Brother, just go straight along the road. Don’t go to the bridge. Don’t go through Chaswal but go through Nanowal. And avoid the side streets of the town. Follow the main road.

BULDEV

(When the WRITER catches up to him.) Before when I was working as a farm laborer and later when I was at Charan’s, these people here used to come and say, “Why do you get your skin picked by them. Come to as, Come with Pala and farm.” (He laughs derisively while behind them SURGIT continues to cry out directions.)

(Scene Nine)

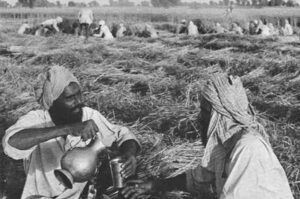

The farmhouse. Three hours later. FATHER, PALA, KAKA and BARA are cooking gur at the underground pit.

PALA

Last night we made bad gur. Because the raas was lying all day. It was too sticky. FATHER

(Feeding cane chaff into the underground fire.) Isn’t it ready yet?

PALA

(Working over a big pan of brown sugar) It’s a little soft still. Kake, go and see the canal so that the wheat field won’t be overflowing. Just turn the water into the second plot and ran back.

FATHER

What if they stop the electricity now? The pump is on. Oh, Pale, the pan leaks. Ooee, come here.

BARA

What?

FATHER

Just attend here to the fire for some time son. I’ll scoop the dirt off the top of the pan. (Clouds of steam rise from the boiling sugar in the large iron pan.)

PALA

Our wheat needs watering quite often these days. It’s getting dry. I went to the fields this morning to have a round. I saw some parts of the earth like stone. First, we will water the wheat, then the oats. Kake, have you done what I said?

KAKA

(Returning, carrying a hoe.) Yes.

PALA

What have you done?

KAKA

I turned the water into the oats.

PALA

Why not into the wheat?

KAKA

The ditch was not clean. It has long grass in it.

PALA

Shall I go myself then?

FATHER

It doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter. You stay here. It’s better.

PALA

Kake, go and fetch a basket to take the gur into the house.

(A little black dog-, one of several around the farm, comes to lick the gar pan, burns his tongue and scampers away, yelping.)

KAKA

(Returning) What’s this in the pan?

PALA

Gur.

KAKA

But it’s black.

PALA

It’s because of that old raas.

FATHER

I think we’ll have to crash more cane. The electricity might stay on all night today.

PALA

I’ll do this job. Forming the gar as it hardens. You don’t know it yet, Kaka. You go and take care of the fire.

FATHER

(Dipping his finger into the cooling gar.) It’s lighter. It’s good. Hand me the water pitcher. It won’t stand now, that funny little thing. Do you think it’s bad gur? It’s very good. You can make good small pieces out of it.

PALA

It’s getting cold. Kaka, put some raas before the pig. I wonder if that pan is leaking. We put quite a lot of raas in and the result is very small.

FATHER

The jackals were in here from the jungle last night. The dogs chased them away. The dogs will let you know if there’s something out there.

PALA

I’ll go and see how is the canal. If it’s not good I’ll stay and clean it. (Leaves for the fields.) FATHER

As you wish. Just help me to take that basket of gur to the house. (Laughs when he mistakes a chunk of wood on the ground for a fallen piece of gur.) Oh, it’s quite a good piece of gur, heh, heh, heh.

SURGIT

(Standing in the hat’s doorway). Look, they’ve hired a tonga. (The WRITER and BULDEV return, the WRITER carrying BULDEV on his back from the tonga offstage BULDEV’s foot is wrapped in a large white surgical bandage.)

WRITER

(Sternly, addressing SURGIT and FATHER) The doctor says Buldev should stay off the foot for a couple of days. He said there was some sepsis due to the thorn prick. It led to pain in the foot, edema and swelling. He dressed it and gave Buldev a shot of penicillin and something else for the pain. If there had been no treatment, the doctor said, then the foot would have taken a month to heal and the, infection might have worsened. They tried to find the thorn by making an incision bat it wasn0t there so they made a small hole to allow the poison to drain out. But Buldev should keep off the foot. Otherwise (he pauses, deliberately) the doctor said he might not be recovered enough to help with the wheat harvest.

(BULDEV, wearing a new shirt the WRITER bought for him in the village, hobbles to a cot in the cowshed and lies down. SURGIT serves the WRITER his lunch on the veranda and then takes back buttermilk, wheat cakes and a potato and pea carry to BULDEV.) (SURGIT speaks in a low whisper to BULDEV.)

SURGIT

You’re avoiding work. You have no trouble.

BULDEV

You heard him. Can’t you see the bandage. It’s hurting. I’m not making encases to get out of work. You know I work hard when I can.

SURGIT

You want to avoid carrying the sugar cane.

BULDEV

It hurts.

SURGIT

Have you got a bullet in it? It’s just a scratch from a thorn and you make herds out of a hair of a sheep. And he bought you a new shirt, did he? It’s insulting, to as if anyone should learn.

(Scene Ten)

Later in the afternoon. The family has received a message that their daughter and son-in-law are coming to spend the night. So they have gone to the nearest village to bay food and liquor to welcome their son-in-law and perhaps meet them on the way. Left behind alone, the WRITER interviews BULDEV on his life’s story.

BULDEV