Le Témoin

Suse, capitale de l’Elam, est situe’ dans la province autrefois fertile du Khuzistan qui prolonge, en Iran, la grande plaine arrosee par le Tigre et l’Euphrate. Aussi sa civilization est elle plus etroitement lies a Celle de la Mesopotamie qu’a celle du Plateau Iran…. Au 13 siecle la celebre ville dont les vestiges presentent un exemple de continuite peut-etre unique dans l’histoire des civilisations, fut abandonee…. Il y a une trentaine d’annees, encore Suse ne comptait plus que quelques maisons groupees autour du tombeau de Daniel. Depuis, cet humble village ne cess de s’agrandier.Peut-etre qu’un jour, graceaux travaux d’irrigation entrepris dans la region, l’antique cite’ retrouvera-t-elle l’éclat de sa grandeur passée.

A brochure of the French Archeological Mission in Iran, 1971Listen again. One Evening at the Close

Of Ramazan, ere the better Moon arose,

In that old Potter’s Shop I stood alone

With the clay Population round in Rows.

And, strange to tell, among that Earthen Lot

Some could articulate, while others not;

And suddenly one more impatient cried –

“Who is the Potter, pray, and who the Pot?”

Then said another – “Surely not in vain

“My Substance from the common Earth was ta’en

“That He who subtly wrought me into Shape

“Should stamp me back to common Earth again.”

The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

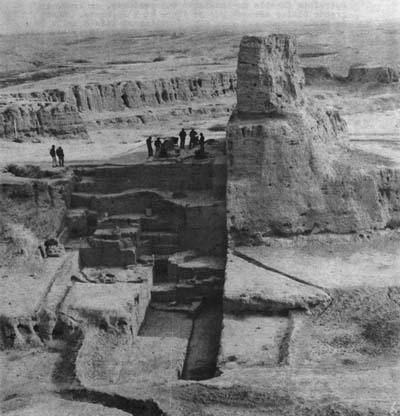

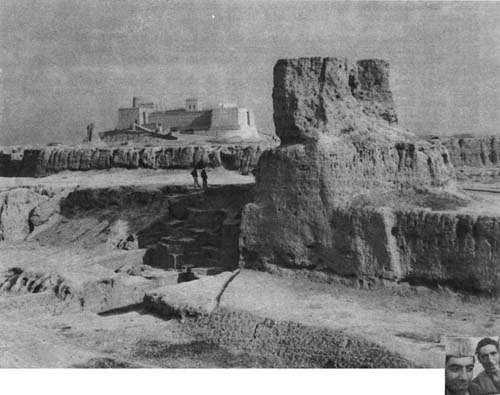

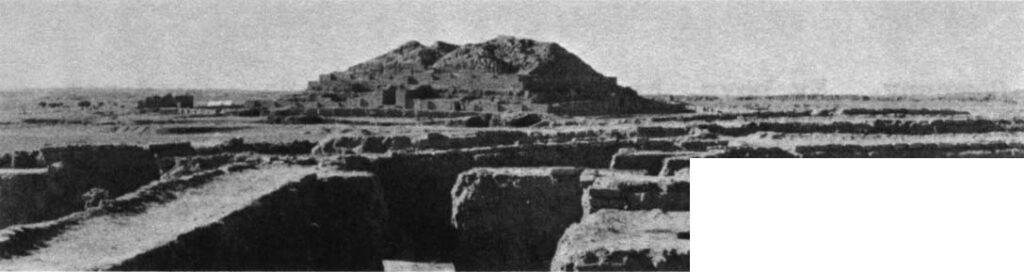

The French archeological mission called it le temoin or “the witness,” the great outcropping of earth and rock that, some distance to the west of the towering Citadel, alone preserved the original height of plateau before excavations were begun a century earlier. To the traveler crossing the Mesopotamian plain, the witness, the Citadel and, indeed, the entire mile-long mound of Susa appeared to rise to a great height; it was not difficult to imagine how imposing the succession of great cities had been, crowned with splendid edifices and probably set in palm-groves and cypress gardens with range after range of the Zagros Mountains rising in the blue distance to snow-capped peaks.

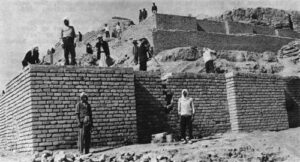

Now it was a vast desolation, diminished and mutilated by man, time and weather. The ruins were divided into six chief quarters. There was the Citadel, its steep-walled pink-bricked ramparts dominating the little village of Shush below and the plain for miles around, built seventy years ago to protect the earlier archeologists from attacks by marauding Arab Bedouin tribes from the desert. To the east of the Citadel, and separated from it by a large depression known in ancient times as the Bazar, sprawled the ruins of the Achaemenian palaces. Here some two hundred workmen toiled, reconstructing the foundation bricks of the palace of Darius the Great, on the basis of its charter found inscribed on stone only a year earlier in February, 1970. Beyond was the Apadana or throne room, a vast structure supported by 72 stone pillars each 22 meters high, identical to the great hall at Persepolis. Some distance to the south, half-hidden in the furthest reaches of the mounds, portions of two Elamite cities had bean excavated, one going back 4,000 years and a second, containing a vast necropole or burial ground, 5,500 years. Below, almost in the village itself, just across the Shauer River from the central square in what had been two years before a wheat field, another group of fifty workmen were unearthing from just a few feet below the surface a pleasure palace built by Ataxerxes II (ascended the throne in 404 B.C.)

While the Citadel appeared to have been inhabited without interruption from prehistoric times down to the Graeco-Persian age, the existence of the towering fortress had precluded excavation there and the oldest dig at Susa was le temoin, which early expeditions had named the “Acropole.” Here giant cuts undertaken over a century by such French as Dieulafoy, de Morgan, Professor Ghirshman and the Comte de Mecquenem had uncovered two prehistoric periods, the earliest dating back to 6000 B.C., 2,000 years after man settled on the plain. Just above the prehistoric zone was a layer of earth some six feet deep in which nothing was found, suggesting the prehistoric city had been destroyed by some higher race. In the next or Archaic zone were found tables of unbaked clay with proto-Elamite cuneiform writing dating from about 4,000 B.C. and in the levels of earth above began the era of written history.

Thus the Acropole, with its diggings reflecting all the ages of civilized man, was rather like a time chart, but not, since digging techniques in the early days were often rudimentary, as exact a one as modern archeologists desired. Some of the greatest treasures of all archeology had been discovered at Susa – the Code of Hammurabi, the stele of Naram Sin, the pyramid of Manishtusu and some of the most exquisite pottery ever designed. It was thus decided to peel away the edges of the cuts made by the early French expeditions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to establish the exact stratigraphic position of the masses of material discovered at Susa in the past.

It was extremely delicate work, especially since the prehistoric Elamite architecture was mud brick which crumbled very easily until the stone palaces of the later Achaemenian kings. One had to carefully clean off layer by layer of earth, inch by inch, from the vast cut in the mountain of erosional debris, applying the latest scientific tests to the substance of the earth, the colors of the soil. To make the work more difficult, the various time zones were not always clearly differentiated, since many of the early inhabitants of Susa had rebuilt their houses from the debris around them, some of it already thousands of years old. Bones had to be sent to Teheran for analysis. Seeds subjected to the developing science of paleobotany to see if the grain had been irrigated and whether it was already domesticated or still grew wild.

So the work progressed slowly, but in this way a relatively accurate sequence of events or “time chart” was being established.

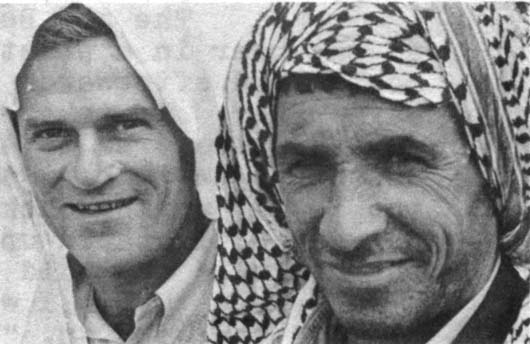

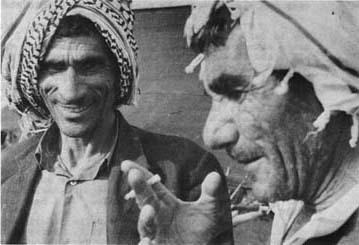

On this particular morning it was very cold, le temoin itself blocking the suns warming rays from the small group of men at work. These included Alain Le Brun, a frizzy, grey-haired but still youthful archeologist; his assistant, Gilvert, [The worker’s version of Gilbert] and their seven workmen, all of them brought from Arrak, a town on the Iranian plateau halfway to Tehran since the local Arabs were too garrulous, sometimes fought among themselves and were not adverse to slipping coins or whatever they found that might be sold for a few riyals to tourists, into their pockets.

“…cinque metre longue et cinque metre de large, n’est pas?,” the archeologist, who was known as “Monsieur Alain” to the workers, was telling his assistant. Then he turned and spoke to Suleiman, the Persian foreman, in the Farsi language, “Dig this deeper. What’s he doing?” Alain gestured toward the gully far below – at the 6000 B.C. level – where one of the workmen, Terabi, sat filing down the spout of an earthen water jug used by the Persian laborers.

“He wants to fix that water jug,” Suleiman, a sunburnt man with his head wrapped in a green cloth against the dust, told the Frenchman. “If the lid doesn’t fit tight, Monsieur, all the dogs, foxes and jackals come and drink our water at night. We leave the water there and we can’t close it now. He’s filing it so we can fit the lid on.”

Alain said nothing but walked to the edge of the cut and shouted down at Terabi, “Don’t do that now. The watchman can fix it tonight. You should be working now.” With that, Alain and Gilvert, wrapping sweaters around their shoulders, went off to talk, pacing back and forth near the dig, their hands in their back pockets and their eyes studying the ground, as was their custom.

When they moved out of eye range one of the workmen, a dark, huskily-built youth known as the “Turk,” jumped with rough gusto down the levels of the cuts crumbling a bank and sending up puff clouds of dust.

Suleiman at once reproofed him. “Monsieur see you, trouble. Don’t you go down like that every time.”

“That’s all right,” the Turk grinned. “Monsieur is not here.” “Go around on the side.”

Kairola, one of the older men, looked up. “Here, Turk, you come and help me dig.”

“No, my job is to put dirt in the basket and throw it into the cart.” Along with Safar Ali, a blond youth with a light-brown moustache and broad, somewhat heavy shoulders, the Turk had early staked out a job for himself that, while more physically demanding, was not so tedious as the slow chipping away of the earth. This task fell to Suleiman, the foreman, and three older men: Kairola, Terabi and Uncle Feruz. A 17 year-old, whom everyone called “Boy,” and who did odd jobs, completed the small work crew.

“Before when I came on the train,” the Turk announced in a loud voice, “one woman wanted to sit by me. I told her, ‘Don’t sit by me; go over there.’ She said, ‘Oh. I didn’t know you are a Turk; I thought you were a Persian.’ Hey, Suleiman, move that way. I want to clean under you.”

Alain and Gilvert returned and stood watching the workmen.

Turk: Put one more basket in the wagon, Ali, and let’s push it down.

Alain: Don’t cut like that’, Suleiman. Just peel it off. Be careful. Be careful.

Suleiman – There’s only one brick and below it is dirt.

Alain: Yes, I know.

Suleiman – Two years, three years, I work for you. You like me, I like you, is good.

Alain: Oui.

Suleiman – C’mon, quick, Ali, gather this dirt

Uncle Feruz: What is the other gentleman’s name?

Alain – Monsieur Gilvert.

Suleiman: How old are you?

Gilvert: Twenty-eight.

Suleiman: I’m thirty-nine years.

Turk: I’m twenty-three.

Suleiman: Here, Turk, clean it up, clean the dirt off, quick.

(The men continue to work as they talk.)

Terabi: One man, Italian. I worked for him. I was assistant to him. He was a carpenter. He worked on Chogha Zanbil.

Turk: How do you say, “Bring this” in Italian?

Terabi: I asked this man, Italian. I said “Monsieur.” He said I am not monsieur. I am signor.” That man, he came to my house and said, “How many boys do you have?” He kissed all the children and then, he kissed all their pictures too, He was very happy man this Italian. He can do every job – pipeman, carpenter, mason, bulldozer, tractor driver, he can do every job. Any job he like. He can do everything.

Turk: is he still in Iran?

Terabi: No, he’s in Italy. He went home.

Turk: You poured out all the water? You didn’t leave a little in the jug?

Terabi: No.

Turk: Before I worked as a mason’s helper. Too much I’m working. This is a lazy job, like playing. The men working over there on the Apadana they have two men just to push the wagons and two men to shovel the dirt out. My old boss, that mason, don’t nobody want to work for him now. Very hard work and he don’t give you good money. In my village. Sometimes I help this mason. He only puts down the lines and a few bricks and after that drinks tea and finish the work for him. He starts it out and I put bricks on top.

Terabi: That water jug looks old but it came from the bazar in Shush.

Turk: I heard that Shush once reached all the way to Shushtar, Seventy-two kilometers. A rooster hopped from one roof to another all the way.

Uncle Feruz: It was a big city in olden times.

Kairola: You know Rustam when he first went to Hindustan, his mother told him to kill a wolf. She told him she’d put his name and what he did in Hindustan in the news. His father, he went first to Hindustan and killed that Baber. His father went to Hindustan and somebody said, “You don’t kill like that. If Rustam comes, we’ll give him a sword and maybe he’ll kill him.”

Terabi: Rustam’s dead. He was a big man. He roamed around England, Hindustan, everywhere.

Kairola: When Rustam, he went to Hindustan, he told the King he wanted to kill that Baber. The king said, “You must have a special weapon, a kanjar.” One time Baber threw Rustam on the ground but Rustam used a Kanjar and killed him. He killed that Baber and brought it home for a cloak. Rustam had this magic cloak…

Turk: You know about his son fights Rustam, without knowing it. His son fights Rustam and throws him to the ground and Rustam says, “You can throw me three times to the ground. If you can do that, the third time you can kill me.” But after two times Rustam, he threw the boy on the ground instead and killed him. He didn’t know it was his son.

Alain: (impatiently) This box is full. Suleiman, have the men bring me two more. Suleiman: Turk, Ali, bring boxes if you want to tell Rustam’s story, why don’t you go and tell it in the teahouse?

Kairola: What time now please?

Suleiman: Ten twenty.

Turk: Take it easy there, Uncle Feruz. Be careful and don’t cut your finger with that pick. You might cut if off.

Alain: This is very interesting, Suleiman. Easy, easy there on the brickwork with your pick.

Turk: How much they pay a man at the Apadana?

Suleiman: Eighty-eight riyals all day. Sometimes they pay overtime.

Turk: My friend, he says he won t come work over here with me. I tell him, No, I got an easy job.” Here we work seven to twelve. Two hours for lunch. Quit at four. Wash. Take a round in the-bazar. It’s all right How many years are you, Uncle Feruz.

Uncle Feruz: I don’t know how many. Many.

Ali: You put one basket, Turk, and I’ll put one. Easy, easy. One time you go first and one time I’ll go first.

Turk: (grinning) Oh, you son of a bitch, Ali, you think you’re working too much. Should I carry this box to the castle, monsieur?

Alain: No. Leave it over there with the toolbox. Did you break this tile? It is broken now.

Terabi: No, Monsieur, it was broken when I uncovered it.

Suleiman: It seems you dug too far. You are not so experienced as yet.

Turk: Let Suleiman play with it. He is more experienced. Whatever more you try to do, the worse it gets.

Uncle Feruz: My feet are frozen. (He sneezes)

Suleiman: Why do you sneeze so much, Uncle Feruz? Did you catch cold?

Uncle Feruz: It is no colder than yesterday but I feel it more.

Turk: We are too tired today from all this hard digging.

Kairola: Hey, Suleiman! I heard you paid five hundred riyals, for a pilgrimage to Meshed.

Suleiman: We paid 220 riyals to go and 230 riyals to get back. (Alain leaves the site to put his sweater with the toolbox some distance away.)

Turk: The Frenchman took off his horse blanket. (Then, calling, in a polite tone) Do these trenches need to be dug out Monsieur?

Alain: (lighting cigarette) Oui.

Suleiman: These French people don’t like anyone to disturb them. Yesterday they told me to prevent anyone from coming near the site. But I don’t always follow their orders.

Alain”, (returning, to Suleiman) the dig begins to become interesting.

Suleiman: Yes, monsieur, it’s becoming interesting. (Alain leaps up to a higher level.)

Turk: He’s jumping too much today. Somebody has brought him some beer today.

Suleiman: Two diesel trucks cannot carry these long names the Frenchmen have.

Terabi: Look! A charred grain of wheat. There must have been a fire here. (Alain comes to examine.) All the famous battles and wars made in this place were only for this one measure of grain.

Turk: I’m hungry already. (A man with a camera appears on the cliff above them. Alain waves him away, calling, “Si vous plait! No photographs.”)

Turk: This Frenchman is like the Mulla Nasrudin; he is of bad temper today. Hey Terabi! You are like a wolf digging with his paws. (Alain and Gilvert stroll off again.)

Suleiman: These French seem ill tempered today. What did they take today? (Two Frenchwomen and two children, clad in bright pink snowsuits, approach the site. Suleiman stands out of respect.)

Suleiman: Salaam khanom. Good morning, ladies.

Turk: Why so polite? A Persian is a Persian to them. Do they understand our language?

Suleiman: No. (One of the Frenchwomen lights a cigarette and stands smoking it, watching the workmen. Alain and Gilvert return and exchange greetings with them. Gilvert stays to converse while Alain abruptly returns to the site and busies himself with some charts as if to indicate he is annoyed by the presence of visitors. The smallest of the two children stumbles and falls and starts to cry.)

Uncle Feruz: Is its foot paining?

Boy: (lifting a heavy box of artifacts) Yah Khoda. Oh, dear God.

Suleiman: If Allah will make the other world so good for these Frenchmen as they enjoy now, then they will have two paradises.

Turk: Yah. I got a four-year-old brother who has a big belly like a pumpkin. Let me bring him here to make a wrestling match with this French kid. My brother is living by eating crumbs but this kid is fattening on enchanted food and is so well fed. He or she is nourished so perfectly while my poor brother must scratch for crumbs to avoid starving.

Suleiman: Those having such a good living on earth may not have salvation in the other world.

Ali: It is not even eleven yet. How slow the time passes.

Turk: These children are so clean. Everyone has a servant in Zoroaster Castle.* This kid is about five years old yet he could not take a cup of tea without someone helping him whereas my poor four-year old brother has to pour even water for himself.

*As the, Citadel is locally known

Terabi: Oh dear, don’t go on so. Let me ask you, who is stronger, you or them? Let there me a wrestling match between you. I am sure you have the power to beat the French. But they work with their heads and that is a drain on the body.

Turk: We always are unshaven but these kharrjoha* shave every morning and get a hot shower every day and we don’t get to bathe sometimes for even a week.

Suleiman: Ah, but, Turk. We are Moslems and a Moslem is like a golden coin which will not rust even if it is buried in the earth for hundreds of years. These people would give off a bad stench if they were not being cleansed every day. (Turning to Alain and shifting from local dialect to standard Persian). Monsieur, Monsieur Alain, look at this piece of stone. It broke by itself. Don’t say afterward that I cracked it by mistake. We must take these stones out.

Alain: What are they?

Suleiman: Only soil; no wall is in evidence here. Look, Monsieur Alain, how all the tiles have fallen. They are all from a fallen wall which has been ruined by water. They were all sun-dried brick which fell at some time into water. Monsieur, from this point up we can find no mud bricks. We should dig the lower parts. This is all rubbish washed down by water. Perhaps a flood. (Alain nods.) Monsieur Alain, what time is it by your watch?

Alain – Ten minutes to twelve.

Suleiman – These tiles are belonging to the upper part. (The Frenchwomen and children go and Alain and Gilvert walk some distance away with them.) These French are of short temper today. Monsieur Alain does not like people to come to the site.

Terabi: Believe it. These French cannot afford to see someone sitting at their table.

Suleiman: Professor Ghirshman was so hot tempered he could see no one stepping into his site. He said people coming here might be harmful. He was absolutely a difficult man to handle. (Alain returns.) Here are two tiles, Monsieur Alain. Let this stay untouched until we dig the other side.

Terabi: Khan went to Mecca.

Uncle Feruz: He is due there today.

Suleiman: He will give us a good story of his trip when he returns.

Turk: Did he go a second time? He is a hadji already. Did he take his wife with him on this journey? He will be called Hadji Ahmad henceforth.

Suleiman: When he is back from Mecca I wish to have sufficient time to sit and hear his story about the journey.

Turk: Who is Ghirshman?

Suleiman: Ghirshman was a man who was wishing to excavate all of Shush within 24 hours. He was such a difficult man who was ever insisting to prove his words.+

Turk: What kind of a gigantic black man was that in the bazar last night?

Suleiman: Maybe from Kuwait or Saudi.

Terabi – Someone said there is a large quantity of snow in Arrak. Last night I wrote my family in a letter to inform me what the thickness of the snow was over there.

Suleiman: Hey, Turk, and Ali! Go slow with the cart. Otherwise you might break a leg.

Uncle Feruz: These young men, are all childish.

Terabi: Remember how Ebrahim’s foot was cut off because of his independent ways. He was too careless.

Alain: (looking over Suleiman s shoulder) It’s red soil but the upper strata is even more reddish.

Suleiman: Yes, yes.

*foreigners

+ R, Chirshman, the eminent French archeologist

Alain: One, two, three….four bricks there.

Uncle Feruz: When I was a boy Monsieur de Mecquenen gave me a ten riyal coin one time. He was fat and carried a parasol. There was a tunnel and I found a gold piece and he took it and put it in his watchcase and I ran home to tell my mother and father. In those days we got only one-and-a-half riyals a day. Now some of the workers get as much as 120 riyals. (A tall, gaunt beggar woman shrouded in a black abas appears and comes up to the site, holding out her hand.)

Uncle Feruz: Why come here? Go to the bazar. Here men are working.

Beggar woman: I have five children. No father. No room.

Uncle Feruz: You are too much lying. My king will give you room. You go around, saying, “Give me baksheesh,” people will think too many poor people in this country. My king not like that.

Woman: Haji, you give me baksheesh.

Boy: Go, go.

Suleiman: It’s not good, to come around here. You go and beg in the bazar. Many gentlemen there, (Gilvert walks off toward the Citadel. The woman follows him, holding out her hand and whining.)

Turk: (laughing) She wants to marry the Frenchman. (all laugh.)

Suleiman: Stop laughing. Monsieur Alain will get angry. I’m digging in the ground. That beggar woman comes, I say, “No, I have no money.” If you give money they’ll come back every day.

Ali: Why should she come here? She can work. She looked very strong.

Suleiman: It is not for bread, for food, this money she wants. Maybe her husband smokes opium. Not only because she is hungry. Maybe her husband is an opium smoker. And she is too.

Ali: Food and bread are very cheap. If she finds some riyals maybe she wants to buy opium.

Suleiman: These Shush people. They get up and go to work early. Four o’clock. I’ve got a room with some workers at the sugar plantation. Some of these Shush people have a good life. If have a shop can open early and close early.

Ali: Yah, the Shush man has a good life. (

Alain gets out a measuring tape and starts to mark the earth.)

Terabi: Was this room a bath room or a sitting room?

Suleiman: Monsieur, look at this. (He has uncovered an alabaster opium box.)

Turk: How do I know if it was a bathroom or a sitting room? My job is to fill the boxes with things we find. We carry them to the castle. The Frenchmen wash and want to see.

Uncle Feruz: For thirty years of rain I’ve seen that earth and it never came down. (He is looking at le temoin.) Thirty years of rain, an earthquake six years ago and a flood two years ago and it never came down.

Alain: (to Turk and Ali) Ca suffit. Don’t overload the wagon, (They push it along some miniature-railroad tracks to a cliff and dump the earth out.)

Turk: The cart holds 500 kilos.

Boy: No, a thousand kilos.

Ali: No, 400.

Suleiman: Maybe 600 kilos.

Terabi: What time now?

Kairola: His watch goes two minutes fast.

Suleiman: No, your watch goes two minutes slow.

Turk: Who’s worked here the longest?

Suleiman: Kairola was here before my time. Before Professor Ghirshman’s time. I worked every year but one with Professor Ghirshman. I only missed one year.

Terabi: I’m sick. I’ve got some dust in my eye.

Alain: When you finish this afternoon you can go to the doctor.

Terabi: It’s too late. The doctor is closed. When I asked before the monsieur in charge let me go to the doctor for one hour.

Alain: All right. You can go to the doctor at three o’clock. Quit work one hour early.

(For some time all work in silence. Then Turk, seeing Alain’s back is turned, picks up a Pebble and throws it at Boy, who retaliates with a handful of dirt. Turk throws another stone and Boy throws more dirt back and then Turk chases Boy behind the cart of dirt. Ali and Turk start to push the cart to the dumping ground but start to run when Boy tries to throw on another basketful of earth and the cart plunges downhill, almost jumping the tracks and going over the cliff.)

Alain: Yewash! Slowly!

Uncle Feruz: Monsieur, I think this is a hoof or horn. (Alain examines what Feruz hands him.)

Turk: (singing)

Don’t go with others

Don’t go with others

You pay no attention to me

In this strange town

(Turk shouts something unintelligible to Ali.)

Ali: Turk, this is the second time today you are abusing me. Watch your tongue.

Turk: I can’t understand you as you speak in your village dialect, Safar, Ali. You say khayah for “egg” whereas we use khayah for testicles. When you say khayah I become angry.

Ali: If you tell me, “Come and drink water from this doul I will be angry too. Because in my village we use doul for penis.

Suleiman: Monsieur, I found this stone.

Alain: Give it to me.

Ali: Hey, boy, did you kill any kaffar last night or not? Hi! What?*

Turk: Hi, did you kill any last night yourself? (Both laugh)

Ali: Hi, Turk don’t you want me to take you to Shush?

Turk: I know Shush better than you do.

Ali: No, you don’t know what places to go where you can have a good time.

Turk: We came here from Arrak just to get out of the cold weather and earn some money here.

Ali: I will kill three kaffars a night if I reach my wife in Arrak. The main problem in winter is this: that you should have a good bath at your house if you would like to get in touch with your wife just to kill a kaffar. [“to kill a kaffar,” literally means to kill someone not included among the “people of the book,” that is Moslems, Jews and Christians; here it is used as a slang phrase meaning sexual intercourse.]

Turk: (laughing and starting to sing again:)

I didn’t do anything bad to you, my darling.

I didn’t.

My only evil deed was to forget you.

Turk: Oh, you son of a bitch, Ali.

Alain (suddenly exploding with surprising vehemence) Shaket! Be Quiet! (For a moment all are frozen. The Turk’s face darkens and he clenches his fists but says nothing. Alain glances nervously at Gilvert and smiles with embarrassment for having lost his temper. The men, all with their faces turned to the ground, seem absorbed in their work, if humiliated.)

Suleiman: (finally breaking the silence) It is twenty minutes after twelve, Monsieur Alain.

Alain: (With some relief) Tatil, tatil! [literally “holiday,” but here means “quitting time.”]

Uncle Feruz: (much louder) Tatil, tatil!

Terabi: Ya khoda. Oh dear generous Allah.

Suleiman: Turk, you stay here today. I’ll send Ali back with tea and kabob.

(Turk does not reply but stands exactly as he did when Alain shouted at him. Alain and Gilvert gather up their sweaters and notebooks and begin to climb the pathway toward the Citadel, chatting with animation. Suleiman end the rest of the crew gather up their picks, shovels and baskets, stack them up neatly by the toolbox and follow the Frenchmen. All of the laborers seemed subdued; even their shoulders seem to sag a little as if all of them, not just Turk, had been reprimanded and humiliated.

Turk waits, until he is alone, then goes to the center of the dig and climbs up to a high ledge of earth on le temoin, crumbling with his heavy boot heels as he goes one of the carefully peeled away edges Alain has been preparing to determine the stratagraphic position of the major finds of the twentieth century. Standing on the high ledge, Turk falls prostrate, then rises to his knees, then stands, during the noontime Islamic prayers toward Mecca. In such a setting, however, he appears less an ordinary Moslem than a prehistoric man, astride this great jutting slab of earth, performing some primordial rite. His prayers completed, Turk turns in the direction of the Citadel.)

Turk: (muttering but with savage anger) I….am….not….dirt.

640 B. C. To The Present

By divine decree destiny was potent of old, and enjoined on Persians to engage in wars, and cavalry routs, and the overthrow of cities.

AeschylusI am Darius, the Great King, the King of Kings, the King of all lands, the King of all the earth, the son of Hystaspes, the Achaemenian.

Inscription on a foundation stone of the palace of Darius at Susa I discovered on February 17 and 18, 1970

[Just as Mark Twain observed when first visiting the Holy Sepulcre in Jerusalem that it seemed Jesus had been crucified by Catholic priests and nuns, so one gets the impression from the new little museum at Shush that Darius was a Frenchman; I envisaged him looking rather like Jean Marais as the prince in “La Belle et le Bete.” One is confronted with a large sign presenting the inscription in French: “Je suis Darius, le grand roi, le roi des rois, le roi des pays, le roi sur cette terre, le fils de Hystaspe, l’Achemenide.” For those interested the ancient Babylonian text read: “A-na-ku M da-ri-ia-mush sharru rabu ‘ (u) shar sharranu shar matatti shar gag-ga-ri mar M ush-ta-as-pi a-ha-ma-ni-ish-shi,” and the ancient Elamite: ” u da-ri-ia-mas-u-ish sunki ir-shair-ra sunki M sunki M sunki-ip-ir-ra sunki sunki da-au-ish-pe-na sunki mu-ru-un-hi uk-ku-ra-ir-ra mi-ish-da-ash-ba sha-akuri M na-ak-ka-man-ru-shi.”]

Ironically, in 640 B.C., the year Assurbanipal vanquished Elam and retired to Babylonia to amass a library that today is the greatest archeological treasure in the British Museum, a new king, Cyrus I, was crowned in the obscure Persian principality that had sprung up in the Bakhtiari foothills west of Susa fifty years before. But so entirely had the grandeur of Susa been forgotten, that when his grandson, Cyrus II, known as Cyrus the Great in history, decided to place his new capital at Susa, Strabo, the Greek historian reported that he did so not only because of the situation of the city on the Elamite plain but also because “it had never of itself undertaken any great enterprise and had always been in subjection to other people.” Sic transit gloria mundi.

Cyrus is, of course, one of the towering figures in human history. Within a single lifetime he toppled the Medes, the semi-overlords of the Iran plateau, and swept over the entire Fertile Crescent to create the first world empire and, incidentally, freeing the Hebrews from the Babylonian yoke.

As put forward in the Book of Ezra: “In the first year of Cyrus king of Persia, the Lord stirred up the spirit of Cyrus king of Persia so that he made a proclamation throughout all his kingdom and also put it in writing: “Thus says Cyrus king of Persia: The Lord, the God of heaven, has given me all the kingdoms of the earth, and he has charged me to build him a house in Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Who is there among you of all his people? His God be with him and let him go up to Jerusalem….”

Cyrus, who ruled from 559 to 530 B.C., also figures prominently in the Book of Daniel, as do his successors, Darius the Great and Ataxerxes. In the year 612 B.C., just 28 years after the fall of Elam, the Assyrian capital of Nineveh had fallen to Babylon and the great Assyrian empire quickly faded into history. Around the year 600 B.C., King Nebuchadnezzar had rebuilt Babylon, creating the famous Hanging Gardens of Semiramis, gigantic palaces, the wide Street of Processions and the great Euphrates Bridge so that the city’s grandeur was unsurpassed in the Fertile Crescent.

In mid-539 B.C. Daniel was a palace page grown to chamberlain in Nebuchadnezzar’s court. When he alone of the royal seers was able to explain a dream of the king, Nebuchadnezzar set him “over all the wise men of Babylon.” In one of his visions, Daniel imagines himself to be in “Susa, the capital, in the province of Elam;” where he was later to serve in the court of Darius the Great and eventually be buried. When Prince Belshazzar, ruling as regent, feasted with vessels from Solomon’s temple, only Daniel could read the words written on the palace wall by a disembodied hand. Daniel told the prince, “Thy kingdom is…given to the Medes and the Persians.” The next morning Belshazzar lay dead; Cyrus the Great ruled Babylon. Daniel still held office but jealous rivals plotted his downfall when they found him flaunting a royal edict by praying to his God; they forced the king to invoke “the law of the Medes and the Persians, which altereth not.” “And they brought Daniel,” the Old Testament tells us, “and cast him into the den of lions.’ The next morning found him unhurt. “My God…hath shut the lions’ mouths,” cried Daniel and his accusers died in the den instead.

The episode over the lions’ den appears to have taken place after the accession of Darius to the Persian throne in 522 B.C. For we are told that Darius was so impressed he “wrote to all the peoples, nations, and languages that dwelt on earth: ‘Peace be multiplied to you. I make a decree, that in all my royal dominion men tremble and fear before the God of Daniel, for he is the living God, enduring for ever, his kingdom shall never be destroyed, and his dominion shall be to the end. He delivers and rescues, in works signs and wonders, in heaven and on earth, he who has saved Daniel from the power of the lions.” And the Bible says, “So this Daniel prospered during the reign of Darius and the reign of Cyrus the Persian.”

This should not suggest that Cyrus and Darius were converted to Judaism; but like the Hebrews the two great Persian kings were monotheistic, worshipping Ahura Mazda, the god of the Zoroastrian religion which had emerged in Persia about a century before their reigns. By now the cultural life of the Middle East had polarized between sacred and secular, temple and palace, priest and courtier and the religions of Zoroaster and the Hebrew prophets were to survive long after the palaces of Nineveh, Babylon and Susa lay in ruins. Zoroastrianism expressly forbade the bloody sacrifices and ritual orgies of the earlier fertility cults. In doctrine it had some similarities with Judaism: the expectation of a fiery day of judgment, when evil would be banished and God’s power be manifested on earth; the belief in immortality combining reward for the righteous and punishment for the wicked; and in such details as the belief in angels. Like Judaism, Zoroastrianism was an attempt to adjust ancestral religious beliefs, formed in nomadry and desert life, to an agricultural and civilized pattern of existence. But in their national careers the Persians and the Hebrews could not have been more different; one had gained the world, the other had lost the Promised Land. So far it has been established that only Darius and his son and heir Xerxes, (the Ahasuerus of the Book of Esther) used definitely Zoroastrian language in their inscriptions. By the reign of King Ataxerxes” (404-359 B.C.) there had been a definite backsliding to the setting up of fertility cult statues in temples, a practice which would have been repugnant to either Cyrus or Darius.

Cyrus divided his realm into twenty administrative regions, each ruled by a satrap, or governor. After his death in 529 B.C., his son and successor, Cambyses, took the obvious step of stretching the empire into Egypt and captured Memphis. Trying to win acceptance as Pharaoh, Cambyses visited the Nile temples and wore Egyptian royal robes but his expeditions up the Nile toward Ethiopia failed.

Darius took the throne in 522 B.C. To consolidate his empire he built a canal between the Nile and the Red Sea noting, “After this canal had been dug as I commanded, ships went from Egypt through the canal to Persia, according to my wish.”

A year after he assumed power, Darius, who had lived as a simple soldier under Cyrus and as the commander of Cambyses’ royal bodyguard, the famed “Ten Thousand Immortals,” in Egypt, sumptuously rebuilt Susa, completing a vast new palace in seven years. It was constructed of cedars from Lebanon, carried by Assyrians down the Euphrates to Babylon where Carians and Ionians took them to Susa. Another precious wood, ebonite, was brought from Gandara and Kurmana; gold from Sardis and Bactria but worked in Susa; silver from Egypt and ivory from the Hindu Kush and India and stone for the throne room’s 72 22-meter high columns from the Iranian plateau but carved by Ionians and Sardinians at Susa. Ivory work was done by Medes and Egyptians and the brickwork by Babylonians. In the palace charter Darius says it is by the favor of Ahura Mazda that so many beautiful things came to Susa and he asks the protection of the divinity for himself and his empire.

As soon as Susa was built Darius constructed an identical series of palaces at Persepolis, far to the east where he wanted a ceremonial capital that would be “secure and beautiful.” The splendor of life at the court in Susa is best described in the book of Esther, the beautiful Jewess who married Darius’ son, Xerxes. (“The King loved Esther above all women….So that he set the royal crown upon her head.”) As is familiar, Esther and her kinsmen foiled a plot to kill the king, then thwarted a pogram against the Hebrews in Susa. Jews today still hail Esther in the Festival of Purim. Xerxes, her husband, is chiefly noted in history for sacking Athens and galvanizing the Greek city states into the great cultural flowering known as the Golden Age of Pericles.

Curiously, there was no apparent extensive program of agricultural development on the Khuzestan Plain (during this period, the province of Elam) when the Achaemenian dynasty ruled much of the civilized world from Susa. (As mentioned earlier, no agricultural settlements definitely dating from this period have been found. On the right bank of the Karun river below the town of Shustar, there are a small group of village ruins which were linked by a new canal dug either by Darius or a successor, but this is some distance from Susa.) Yet it is known that the court of Darius numbered well over fifteen thousand people, two-thirds of whom were soldiers, part of imperial army of 120,000 men. Darius introduced coinage to the empire which was the only gold currency of the ancient world and taxes in kind were also heavy, Babylon feeding the court and a third of the army and Egypt providing corn for around l50,000 persons annually. The Medes furnished the court horses, mules and sheep, the Armenians foals and the Babylonians eunuchs, some of whom became royal chamberlains and were a powerful influence in the palace. The Greek historian, Herodotus, provides a great many details about Darius’ military campaigns, but of the basic agriculture around the capital city we remain largely ignorant.

The introduction of coinage did allow for the development of banks which we know held leases, dug canals and sold water to peasants. And there was a high land tax that discouraged individual farming. As developed late in the Elamite kingdoms of the earlier age, estates and temples, with large retinues of serfs and slaves, continued to be the heart of agricultural and economic life. These large estates could be bought and sold and their serfs, mostly captured slaves, were part of the sale. Only in the highland province of Fars, the original home of the Persians, did many owner-farmers seem to till their own land. Wheat, barley, oats, grapes and olives were common crops and cattle, sheep, goats, donkeys, mules and horses raised. Bee-keeping was becoming widespread as a source for sugar.

Especially on the Iranian plateau life had become much as it was in Medieval Europe with prince, nobles, free men, owning or not owning land and slaves. Already there were signs of slaves and peasantry and the non-propertied classes beginning to struggle against the nobility.

The camel, first domesticated in 1,000 B.C., now came into common usage and was even used by Darius for his cavalry. But the diet of the common man was now poorer than it had been in the early days of Elam and consisted of little more than bread, fish, a little oil and wine.

Also, during this period we see the growth of a hybrid economy, with agriculture starting to experience a splitting up into smaller and smaller subsistence units while the kings and rulers were primarily interested in the great traditional centers and trading entrepots. Toward the end of the Achaemenian period, around 350 B.C., we find the first evidence that the plow has been introduced in China.

One last note on the Achaemenians. It is interesting to note how many of the Hebrew prophets either lived in Susa or refer to the reigns of the successive Persian rulers of the time. These include, besides Daniel, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, the second Isaiah and Ezra, Nehemiah, Haggai and Zechariah. On the eve of Alexander the Great’s march into Asia in 334 B.C., the Old Testament ends, with its future promise, perhaps best put in Isaiah 52: “How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of him that bringeth good tidings, that publisheth peace….”

The second Isaiah lived and wrote during the lifetime of Cyrus the Great and it was at the tomb of Cyrus at Pasargadae, that the young Macedonian, Alexander, would read: “O man, whosoever thou art and whencesoever thou comest, for I know that thou wilt come, I am Cyrus, son of Cambyses, and I won for the Persians their empire. Do not, therefore, begrudge me this little earth that covers my body.” (The source for this scene was Plutarch.)

The court of Susa had been implicated in the assassination of King Philip, Alexander’s father, but after crossing the Dardanelles and capturing the mother, wife and children of Darius III, the last of the Achaemenian rulers, and defeating him at Gaugamela in the foothills of the Assyrian mountains in 331 B.C., Alexander treated the family well and restored them to their palace at Susa. Why he should later burn and sack Persepolis, which was in effect already his possession, remains a mystery and many historians simply believe Alexander was drunk at the time.

At any rate, Susa’s last great blaze of glory came in 325 B.C. when Alexander returned to the City from India for his triumphal celebration. During five days of festivities, Alexander married Statira, the daughter of Darius III (who was murdered by his men while fleeing the Macedonian forces), and ten thousand Greek soldiers took Persian brides in what Alexander hoped would be a fusion of peoples. Alexander rested in Susa almost two years, embarking in 323 B.C. on a campaign against Carthage. But he got no farther than Babylon, and, after his entire army passed by his deathbed, expired at the age of 32. (Statira was murdered soon after by Roxana, Alexander’s Greek wife, during the bloody succession struggle that followed.)

From then until the rule of the Parthians began in 140 B.C. Susa and the Elamite plain were ruled by Alexander’s Seleucid heirs. The people of Susa adopted Greek culture, spoke the Greek language and there was a general renaissance of settled urban life in what had been ancient Elam. Under the Parthians, a Greek garrison remained at Susa, and some impressive irrigation works were undertaken which can still be seen in aerial photos today. A considerable program of canal building was underway, the population grew but, with the center of culture and power now shifting to the Iranian plateau, little of major historical importance occurred.

Then, during the rule of the Sassanides (226-637 A.D.) a massive transformation of the Mesopotamian plain east of the Tigris or what is modern Khuzestan was undertaken to extend irrigation over all arable land. Much of the engineering is believed to have been done by Romans – some of the 70,000 Roman legionnaires captured in 260 A.D. with the aged Emperor Valerian by King Shapur at Edessa.

Most of these captured Romans are believed to have eventually settled down near Susa, forming the still-existing town of Dezful, whose inhabitants even today look more Italian than Persian. Valerian himself, according to legend, was forced in his hapless old age to serve as a mounting block for his conqueror and that his body was flayed after death and the skin kept on as a trophy. Certainly, the capture of a Roman Caesar in his royal purple produced a great moral effect on the young Sassanian dynasty.

Even today, the great irrigation system the Sassanians built on the Khuzestan plain has never been surpassed and must have required a great deal of planning and administration, many technical innovations and a massive investment of state funds.

Unlike most modern agriculture development programs, however, it aimed at increasing food production by extending the area of cultivation rather than by introducing more intensive farming and increasing labor productivity. In this way it can be compared with the efforts of India and Pakistan to expand their areas of cultivation after independence in 1947.

Great weirs of stone and brick were constructed across the Karkheh River at Pa-i-Pol, the Dez River at Dezful and the Karun River at Shushtar and the present city of Ahwaz, which radiated canal networks to provide more reliable winter irrigation to the whole of Khuzestan.

There was no storage system; a weir, or what we call a diversion dam, diverting low flows but allowing flood waters to pass over it. The major construction work took place during the reign of Chosroes I (531-579 A.D.) There was an extensive use of tunnels with periodic vent holes – usually a shaft going down every 25 meters – not only as subsurface conduits through ridges but also as collection for ground water. Essentially these were of two types: (1) tunnels to tap ground water extending horizontally down sloped ground until daylight was reached, and (2) tunnels which ran from deep river beds straight across until a slope reached daylight. The longest was fifteen kilometers. While dozens of such tunnels were built, most of them have caved in or been destroyed although five still remain in use today! (as well as hundreds elsewhere.)[ Reference here is made only to Khuzestan] Another innovation was the construction of an inverted siphon to carry a large canal across a seasonal water course. Such siphons were introduced in the United States only five years ago.

As part of this agricultural development program, the Sassanians put great stress on commercial crops and handicraft industries, including the manufacture of fine silks, satins, brocades, cotton and woolen textiles. In some areas, new populations were added through the settlement of prisoners. Cities grew up and Susa, which had risen and fallen so many times, was once more extensively reconstructed. The total population of Khuzestan (Elam and the southern reaches of the plain) reached an all-time high, perhaps four to five million people. At its zenith greater Mesopotamia in ancient times was believed to have reached more than 12 million people as compared to modern Iraq’s population of around 7 million.) For the first time in history, agricultural settlements began to thrive well south of Ahwaz on land that formerly had been below sea level and was covered by the Persian Gulf. A university was founded at Jundi Shapur by King Shapur II which became a famed center for astrological, theological and medical learning. A hospital was built, as well as a great pharmacopoeia and the growth of a market economy had spurred trade with all the great entrepots of the Middle East.

It should be remembered that all this happened nearly a thousand years before the first, medieval, revolution of agriculture in Europe. And then in 570 A.D., Mohammed, whom I have previously called the last of the desert prophets of the Hebrew, Christian and Islamic religions was born. This, I believe, represented a significant setback for technological development in the Middle East, especially in agriculture, because Islam represented a return to the stern and just God of war and the desert, a return to the old religion of Abraham before it had been adapted to meet the needs of agricultural and civilized, indeed, Hellenized, societies.

It seems quite clear from any careful reading of the Koran that Mohammed regarded himself as only the latest in the long line of prophets that began in 750 B.C. with Amos, continued for six hundred years to the author of the Book of Daniel (ca. 150 B.C.) and beyond to the teachings of Jesus of Nasareth (ca. 30-34 A.D.) The themes of his early preaching were simple; he proclaimed the existence of one God, Allah, the terror of Allah’s impending Day of Judgment, and the duty of each human being to obey the will of Allah as revealed by his latest prophet, Mohammed. Allah was conceived as the same deity who had earlier revealed himself through Jesus and the Hebrew prophets. In his early years, Mohammed appears to have assumed that the adherents of Judaism and Christianity would recognize him as God’s last, latest, and hence most authentic messenger. The Koran, after all, is mostly peopled with figures out of the Old and New Testaments. Only when he removed with his followers to Medina (622 A.D.) and came into close contact and conflict with the Jewish tribes already settled in that oasis did he recognize the futility of his assumption. Thereafter, he declared that Jews and Christians had so corrupted and forgotten the Divine revelation as to reject undiluted truth. He declared himself spokesman of the authentic “religion of Abraham.”

The preaching’s of Mohammed in the past twelve hundred years seem to have had two main effects on the Middle East, the birthplace of the religions of both Abraham and Jesus. One is that nowhere else in the world has agriculture remained so backward and technologically retarded and the second is that nowhere else in the world does any religion have such a strong and profound effect on the daily lives of its adherents. In a secular, spiritually rootless age, Moslems seem about the only “true believers”[Figures from George M. Adams, see earlier reference] left in large numbers. Indeed, where much material progress has been made in the Middle East, the modernizers have been men who have had to virtually compartmentalize their minds to keep their religious beliefs and their secular concerns entirely apart.

Also, logically, a Christian or Jew cannot peacefully coexist with a Moslem, as easily as -they can, theologically speaking, with each other. For them either Mohammed was an imposter or the latest and hence the most valid prophet through which God has revealed his divine will. This contradiction and the accompanying tensions that go with it, has yet to be resolved.

In 639 A.D. the Arab armies, bearing the banner of Islam before them, came to Khuzestan to conquer and convert. At first, the effect was relatively mild. By this time, Khuzestan’s tax payments included twenty tons of refined sugar and most of the sugar traded at the eastern Caliphate in Baghdad. At a normal market price of about $3.30 per kilogram – enough to keep a couple in modest circumstances for a month at contemporary prices – Khuzestan was flourishing. Rice, observed growing in Khuzestan by Alexander’s time, only now became an important item in the diet.

Indeed, in the early days of the Arab rule, Susa experienced a cultural renaissance, especially in lustrous polychrome ceramics and a great variety of vases and dishware. The tomb of Daniel, whom Ali, Mohammed’s cousin and son-in-law, called the “greatest of the prophets” became an important place of pilgrimage for Moslems of the Shi’a sect, (who, unlike Sunni Moslems, support Ali’s claim to the Caliphate in Baghdad.)

Agriculture, however, began to decline with the arrival of Islam. In late Sassanian times, tax receipts from Khuzestan had been over $5 million, around 12 times more than the tribute exacted from the same area by the Achaemenian kings a thousand years earlier. [As compared with the nominal religiosity but actual secularism of the Punjabis and Javanese.]

By 900 A.D. they had fallen below $2 million, which indicates that a gradual but steep decline had set in well before the onset of Genghis Khan and his Mongol hordes and the massacre of millions of Persians and destruction of the Persian cities plunged Iran into a setback it is only now recovering from. By 1,300 A.D. tax receipts had fallen to less than the equivalent of $300,000 or considerably below what they had been in the sparsely populated days of Cyrus the Great.

Various reasons have been cited for the decline of agriculture under Arab rule. Aside from my own thesis of the incompatibility of technological progress and orthodox Islam, farming in Elam was heavily taxed, the Abbaside Caliphate after 900 A.D. grew increasingly corrupt and inefficient, the citizen soldiers of the Hellenistic period were replaced by mercenary bands who looted the peasants, the instability that accompanied the breakup of the Caliphate created unrest in the countryside and finally, the death blow dealt by the barbarian Mongols.

Another contributing factor might have been the increasing reliance during the eighth and ninth centuries on slave labor, which culminated in the Great Slave Rebellion in lower Khuzestan and the lower Tigris Valley from 864 to 883 A.D. In this wet country of swamps and marshland, hundreds of thousands of slaves were employed in the attempted physical removal of the saline surface crust. The slaves mostly known as Zanj (after the East African slave city of Zanzibar), fought for fourteen years during which many of the Khuzestan towns were damaged. (One still sees an occasional black descendant of these slaves in the streets of Shush.)

In the 12th century there were still references to Susa as a thriving mercantile and textile center and in 1170 A.D. a visiting rabbi reported 7,000 Jews numbered among the inhabitants. After Baghdad was sacked by the Mongols in 1258 A.D. little more is known, although there is a record of Susa. Having been precipitately and temporarily abandoned in a local military action. Local tradition holds that Tamerlane finally destroyed Susa in the 14th century and although a local village bears his name the French archeologists maintain that Tamerlane never came that far (it is known he reached nearby Dezful, where he built a still-standing mosque.)

What is known is that Susa, having endured as a great world city longer than any other in the history of man, had vanished entirely when British and French explorers ventured into Khuzestan in the l9th century and that Ahwaz, today a city and the provincial capital, was then only a small village. By then the only other surviving villages were near the small towns of Shustar and Dezful, just below the foothills of the Zagros Mountains, although it is possible these had indeed preserved some agricultural continuity from the earliest Neolithic times. (In a similar example of depopulation, the number of people in Mexico fell from 11 million at the time of the Spaniards’ arrival in 1519 to 2.5 million by 1600 and to 1.5 million by 1650 A.D.)

(A somewhat similar agricultural decline occurred in 18th century China. Peasant distress arose because (1) excessive population growth caused too much subdivision of the land until in bad seasons the tiny farms could no longer sustain a family and (2) amidst the helpless peasant indebtedness and sporadic foreclosures that followed both opium smoking and peasant rebellions became widespread.)

One can probably put 1000 A.D. as the date when agriculture, the basis of civilization until the industrial age and to some degree afterward, was conspicuously in decline in the Middle East and rapidly beginning to ascend in Europe. For by 1000 A.D. heavy mold-board plows were generally in use in Europe. This technological breakthrough made possible and necessary the new manorial system of farming in Europe which in turn created the agricultural surpluses on which the military advance of Northwest Europe depended.

Between 1000 and 1500 A.D. European farming went commercial. This, of course, reflected the expansion of the commercial economy of the medieval towns and cities (and the Protestant Reformation, which, though intended to achieve a sanctification of all human activities before God – not only crop-raising and sheep-herding – led to an application to the business of making money such as the world had never before witnessed.)

In the most active centers, calculations of price and profit began to introduce modifications in crop rotation and methods of cultivation and in the balance between animal husbandry (mostly sheep raising) and crop production. The treatment as commercially negotiable commodities even began to extend to lands and rents. In result, for the first time in history, an absolute majority of the peasantry ceased to find their lives circumscribed by traditional agricultural tasks and traditional ways of thinking and values. Instead they faced the troubling ups and downs of a market economy in which a few grew rich, some prospered, while many became paupers, so many indeed, that by the 18th and 19th centuries, some forty million would migrate to the United States in human history’s greatest mass movement of peoples.

The cost, in uncertainty about the future, in the substitution of monetary for human values, in removing life of much of its poetry, was very great, especially for the poor. (This is the process now taking place in Asia’s agricultural revolution of the 1960s and 1970s). But the growing market economy of Europe, supported by cheap water carriage of bulk commodities, was a potent lever for raising up European power and wealth far above that attained elsewhere. In the 14th and 15th centuries Russia too began to undergo its agricultural revolution. First under Mongol (or Tartar) overlords and then under Russian princes a vast work was carried out of cutting down forests and taming the land for agriculture so that the Russian population ceased to be concentrated principally along the river banks, as in Kievan times, with the hinterlands left largely to hunters and fur trappers. A numerous agricultural population developed, which, under a unified and centralized state, formed the basis for the emergence of modern Russia. This story, though less familiar than that of the settlement of the United States, centered around the problems of labor shortages encountered on any expanding frontier. These could be solved in either of two ways with the Russians favoring the first and the Americans the second;(1) drastic compulsion to sustain social stratification or (2) drastic liberty with concommitant regression toward an equalitarian neo-barbarism (as in the old Wild West, where man came close at times to reliving his lost Neolithic, anarchic Paradise.) [As he does in contemporary, urbanized America watching television ‘Westerns; the old atavistic, hunting instincts are still strong.]

During the 19th century, man undertook an unparalleled amount of tinkering and manipulating with the forces of nature, as he had first started to do by introducing the traction plow and the irrigation ditch in Elam at the beginning of our story. In agriculture, Britain took the lead in developing new technology such as the systematic-selection of seeds, careful breeding of animals for special traits and the introduction or spread of new crops like clover, turnips, potatoes, maize, cotton and tobacco, which worked tremendous new increases of productivity on the farms. Tests were undertaken to learn the best shapes for plowshares, the benefits of repeated tillage, elimination of weeds, drainage and application of manures and chemical fertilizers. This British breakthrough seems to have been caused by the English landowners being in a position to impose new methods on farm laborers, since in most parts of Europe peasants stuck to old methods and only slowly adopted the new agricultural methods.

Charles Darwin (d. 1882), of course, had an enormous influence on agricultural research with his famous book, On the Origin of species, which brought all living things within the scope of a single evolutionary process. (Part of Darwin’s data, on his voyage with the Beagle, was collected on the island of Mauritius. See RC 1 & 2). Geologists and paleontologists soon added to Darwin’s picture of human life and history dwarfed by the immensity of geological and biological time. [Not to slight Gregor Mendel (d. i884), who, although he wrote his great paper in his Austrian monastery in 1865, was not confirmed by de Vries, Correno and Tshcernak in three -separate researches until 1900.] Most important, Darwin, by reducing human beings to the level of other animals, subject to the same laws of natural selection and struggle for survival, shook the very foundations of the religious and social order as well as the refinement of all human culture. There were those who seized on Darwin’s theory to justify a ruthless economic individualism at home and an equally ruthless imperialism abroad. It was not long before Sigmund Freud (d. 1939) concluded the ruling drives of mankind resided in an unconscious level of the mind or Karl Marx (d. 1883) produced his vision of the stages of the human past and future – from slavery to serfdom to the financial exploitation of the free market onto the perfect freedom of socialist and communist society. And only in the past decade have we seen the application of all three men’s ideas, plus those of Lenin, to the frightening mass manipulation of a society through exploitations of internal contradictions as has been done with such signal success in his struggle against South Vietnam and the United States by Hanoi’s Le Duan, b. 1907). [Who is but one of many now developing revolutionary ideologies.]

But one of the great contributions by Darwin was to the science of plant genetics. The technological lead in agriculture held by the English shifted to the United States in about 1890. During the period that began just before the Civil War, or about 1860, to around 1910, the United States experienced the accumulation of a great deal of basic agricultural research, mostly due to the creation of land grant universities and colleges, the establishment of the agricultural extension services and the passage of the Hatch Act. [Key legislation was Morrill Land Grant College Act of 1862 end the Hatch Experimental Station Act of 1887; today USDA employs 108,500 employees] Then from about 1910 to 1940, the eve of World War II, there followed a tremendous increased in total American farm production, much of it due to the farming of new, virgin lands, especially on the Great Plains of the Middle West. The third phase of American agricultural development took place starting around 1935 but did not really pick up speed until the start of the war in 1941; this was a tremendous increase in production per acre through new seeds, irrigation, more efficient usage of tillage tools and the massive application of fertilizer, as well as mechanization. This resulted in what can be called the American Agricultural Revolution of the 1940s which left Congress and the White House with headaches unsolved to this day.

Developing simultaneously with the changes in America was the quiet, patient research by Dr. Ernest Borlaug and others with the Rockefeller Foundation in Mexico of the dwarf wheat – and later in the Philippines – rice, that is now transforming – since 1964 – agriculture in much of the rest of the world. This phenomenon has been discussed in some depth in earlier reports.

Perhaps the most scientific agriculture – since most easily man controlled – has been that developed in the formerly semi-arid deserts which are now irrigated farms in the Imperial Valley and San Joaquin Valley in California and a few other irrigated areas in that state and Arizona. Here deserts have literally been made to bloom with the construction of such works as the 500-mile-long California Aqueduct (which was seen by the astronauts from the moon in 1969). Once the success of such mammoth reclamation projects in the American southwest was dramatized, the obvious question was: Could the same be done for the Middle East? Can the Fertile Crescent be reclaimed?

The question was – and is – an urgent one and during the past few years Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, Egypt and Israel have been either digging canal’s or been planning them. Israel, where most of the preliminary canal work was done in the early 1960s, and Egypt which has dug more than 400 miles already aside from the huge Aswan Dam project whose completion was dedicated last month, have taken the lead.

The problems facing the nation-states of the Middle East today are, in a political sense, not so unlike those faced by the neighbors of Sumer or Assyria or Persia during each one’s period of ascendancy. Sumer was predominant because of its literacy and early civilization, the Assyrians because they developed the wheeled-chariot and use of a horse cavalry, Persia, partly because of the camels introduced into his cavalry by Cyrus and his very wise politics. For the past fifty years in all of the modern Middle East countries, history has been rather like a race between the growing powers – Russia and America, now that Europe has faded, however temporarily, and the increasingly desperate efforts of the small Middle Eastern nations to stave them off by appropriating the West’s technology in the hope of thereby finding means to preserve their local autonomy. At present the greatest threat to national survival in this part of the world is the new element of Soviet expansion into the Indian Ocean. In the 16th century, tiny Portugal was able to control the trade in the Indian Ocean by holding Goa on India’s coast, Malacca and Diu. A century later the Dutch were able to do the same thing – that is, dominate trade in the world’s most strategic waters by holding Java, capturing Malacca and seizing some bases on Ceylon. There is little reason to question the Soviet Union’s ability, in light of its vast naval buildup of recent years, to repeat the experience of the Portuguese and Dutch, now that the British have effectively withdrawn East of Suez. Then there is, of course, the population explosion, caused by a cataclysmic fall in the death rate of most countries with the introduction of modern medicine and sanitation fifty years ago and sharply intensified by the post-war use of DDT to eradicate malaria.

In Iran alone the death rate has dropped from around 30 or 40 to 15 per thousand while the birth rate has remained at 50 per thousand. This means Iran’s present population growth rate of 3 per cent will soon reach 3.5 per cent. The conclusion of most experts is that Iran’s population will reach 50 million (it is 30 million now) by 1980 and that it could even double, Elsewhere in the country a water shortage could be a drag on rising living standards, even if Khuzestan is transformed. Much of this was forecast in the population and resources projections made in the 1950s. At that time, Mohammad Resa Shah Pahlavi, the present Shah of Iran, or, if you will, the king of Persia, was still a young man in his late thirties who began to think of Khuzestan, the deserted plain of ancient Elam, as “our national salvation.” At about this time Iranians themselves had begun to talk of a new renaissance headed, as all the previous ones had been, by a fresh dynasty. Iranians referred to the king, as they now do, as His Imperial Majesty, King of Kings, Light of the Aryans. If this sounded self-conscious; it was meant to be. There were hopes that given the king’s longevity and a period of stability, there might indeed be another Persia. At a World Bank meeting at Istanbul in 1955, some of the Shah’s planners invited David E. Lilienthal, former chairman of the Tennessee Valley Authority to tour Khuzestan. During the tour, in 1956, Lilienthal was persuaded that his New York based consulting firm, Development Resources Corporation, should produce a blueprint for Khuzestan.

By 1959, Lilienthal’s staff produced a plan for the unified development of the natural resources of the Khuzestan region.” It was a multi-billion-dollar undertaking that would take many years to complete, it called for fourteen dams in Khuzestan, 66,000 megawatts of power production and hundreds of miles of canals to irrigate some 2,500,000 acres.

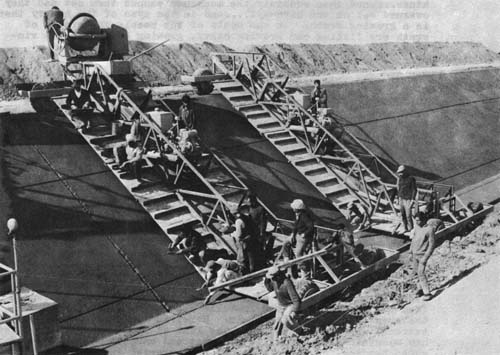

The Shah ordered work begun at once. While the first project – dam, powerhouse and canal – was being constructed on the Dez River, Lilienthal’s experts sought a quick showpiece that would convince prospective investors that large scale farming could pay off in the province. (The basic difference between what is called he Dez River and the Sassanian irrigation scheme for Elam 2,000 years before is that the Roman engineers of the Sassanians built their major dam on the Karkheh River not the Dez, a few miles to the east. The Dez flows down a steep gorge and provides a perfect setting for a storage lake to guarantee a minimum summer flow. The Sassanians and the Romans could have built such a dam – they had the materials and manpower – but lacked the necessary technology to construct a tunnel or conduit at the bottom of the dam to let a controlled amount of water through. In this the new Pahlavi Dam and the other dams planned, including one across the Karkheh near the old Sassanian site, and other advances planned by the Khuzestan Water and Power Authority (modeled after the TVA) represent a much greater manipulation of nature since they will eliminate the danger of floods and drought entirely.)

A showpiece was found in sugar cane. Arab historians in the 12th century had written of cane growing “in the plain as far as the eye could see.” But modern Iran was short of sugar. Today at Haft Tapeh (or “Seven hills,” named after the existence of seven large burial mounds in the area) 13,000 acres produce one of the world’s highest unit yields nearly five tons of refined sugar per acre. The acreage is currently being doubled and a new $30 million paper plant, Iran’s first, is now running to make better use of cane fiber.

The initial intent of the Shah and Lilienthal and his planners was that the renaissance of Khuzestan could be done by the scattered population of traditional farmers living there. (At the present time the total population of Khuzestan is 2.5 million of which 60 per cent live in the big oil towns near the Persian Gulf on lands that during ancient times up to the arrival of Alexander the Great and after were still underwater as part of the Persian Gulf. Thus the real current population of what was ancient Elam is only 173,888. Of these only about 68,000 people live in villages and the rest in the presently booming towns of Dezful and Andimeshk. Shush today has about 7,000 inhabitants.)

The aim was to reclaim the land and productivity which had existed 2,000 years ago under the Sassanians. (One is commonly told the period of agricultural decline only lasted 700 years but this is highly inaccurate.)

At first the government gave the local farmers free fertilizer. When some refused to use it, arguing it was against the will of Allah and unnatural, the Khuzestan Water and Power Authority (KWPA) forcibly put it on. After that fertilizer gained acceptance and even popularity. But the area did not develop into huge mechanized farms or show any signs of moving that direction. The canals and water distribution system had been built to serve traditional farming but it was decided some other way had to be found to get the region into huge mechanized farms using the latest technology.

The Shah first had to break the back of the area’s landlords, mostly feudalistic Arab sheikhs. In sweeping land reform, as throughout Iran, by four years ago he had pretty well seen that each strip of land in the villages was distributed to those actually farming it. While production jogged along fairly well, the farmers still found they lacked the means to really modernize. No credit, no money, no machinery on a big scale. Individual farmer-owners couldn’t make it.

By then, around the town of Andimeshk some 30 miles north of Shush (Susa), a regulated supply of Dez River water was already available, coursing through concrete channels to the first 50,000 acres of the Dez Irrigation Project. When the canals are completed in 1973, water will be available for 250,000 acres, many of them long desert. The new Dam, named after the Shah or Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi Dam, which blocks the Dez River in a narrow gorge above Andimeshk is the highest in the Middle East at 647 feet and cost $85 million; it will produce 520,000 kilowatts of electricity…plus provide a year round supply of water for the plain.

In the end a decision was made to try bringing in big, privately financed developments, the kind of “agribusiness” which had transformed the desert valleys of California with its big capital and big technology. Two American companies came first and each was given a thirty-year lease. The land of 58 villages was preempted for their use and the farm families who owned them reimbursed.

The biggest company was headed by Hashem Naraghi, a 52-year old native-born Iranian who had learned English from some of the 28,000 American troops stationed in Andimeshk during World War II. (The highway from the Persian Gulf to the Caspian Sea, Russia’s sole lifeline during most of the war, passes a mile east of Shush.) Accompanying the troops to the U.S., Naraghi arrived with only $1,400 in 1944. He bought a tractor and started leveling land for California farmers. In time, he made enough money to buy his own spread in San Joaquin County, where he now has 11,000 acres in nuts, fruits and row crops. Now the “world’s largest almond grower,” with a country home that resembles a medieval castle, Naraghi had made himself a millionaire several times over. In an interview with Fortune magazine last year, he was quoted as saying, “with enough water for irrigation, enough power for processing plants, and enough insecticides and fertilizers from petrochemical plants nearby, success is almost guaranteed. Anyone who can’t make it in Khuzestan has no business being a farmer.”

The second company (a third has just been announced, owned by Royal Dutch Shell) had a somewhat different character. It was headed by George Wilson, 78, who headed the California Farm Bureau Federation from 1951 to 1955 who had first laid eyes on Khuzestan back in 1949 when he flew over it enroute from Iraq to Pakistan. Fortune quoted him as saying, “I saw those big rivers and all that land laying there, and it looked gol-darned good to a farmer like me. I thought then I’d like to have a piece of it someday.” Wilson’s company, in which some $10 million will eventually be invested, is a joint venture of Wilson’s Trans World Agricultural Development Company, Iranian private investors, Dow Chemical, Deere Company and the Bank of America. Called “Iran-California Co.” it plans a broad agricultural mix of wheat, cotton, sugar beets, alfalfa, oil seeds, winter vegetables and dairying.

Naraghi has invested $3 million in his first 10,000 acres and expects to invest a total of $10 million into the 45,000 acres he ultimately plans to work. Fortune also quoted him as saying, “Labor cost is one tenth of what it is in California and almost everything does well. Asparagus grows faster here than in California and with a better root system. I can get ten cuts of alfalfa here a year and the protein content of Khuzestan alfalfa is higher than any other in the world.” By early 1971, Naraghi was airlifting asparagus to Europe’s winter markets, pelletizing alfalfa for export to Japan and planting 5,000 acres in oranges and lemons, tomatoes, table grapes and strawberries, planning to can what he couldn’t sell fresh.

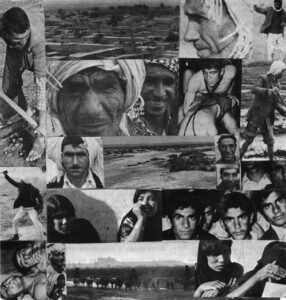

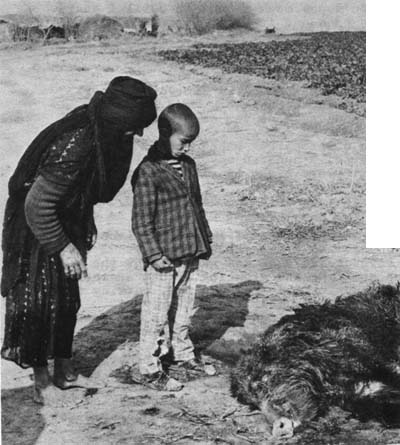

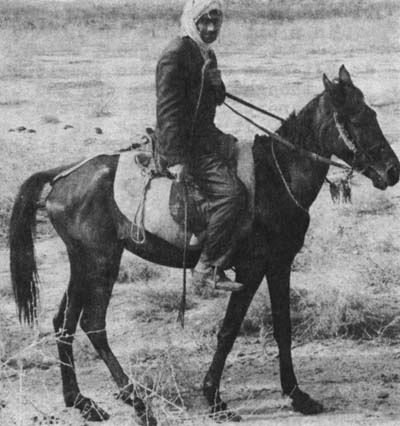

Understandably the transformation of Elam, where the first breakthroughs in agriculture had come eight and nine thousand years before, attracted widespread attention. There were some critics. The World Bank’s Wolf Ladijinsky pointed out, not always coolly, that a disproportionate share of Iran’s resources was being awarded a minute part of the farm land that needed help. Iran had not the resources, he argued, to absorb in industry and agribusiness the huge new labor force that would be created by a modern equivalent of a wholesale “enclosure” movement. He favored devoting more attention instead to the nation’s largest semi-skilled force: the small farmer, who in many parts of the country had not progressed much beyond the agriculture of the Neolithic age. If there were ghosts in the old ruins of Susa they could only watch and wait. Until thirty years before the few houses clustered around Daniel’s Tomb had been at the mercy of roaming desert Bedouins who four times since then had burnt and sacked the town. Even as late as November, 1970, a dozen horse-borne Arab Bedouins one night had ridden up to Shush after dark and, in a furious exchange of-rifle fire with the local police post, had shot and killed a village farmer in a still unsettled blood feud.

Just west of Shush in the jungle along the Karkheh River, leopards and hyenas roamed and great yellow-tusked boars as big as oxen thrashed through the underbrush; beyond the river was a no-man’s land where no law existed but tooth and claw and a man could be picked to pieces by the Bedouins and left for dead. Most felt it was a blessing that civilization, in whatever Garb, was coming home again, back to its birthplace.

Fellahin