A study in four parts of the human impact of the new seeds and methods of cultivation in Ghungrali-Rajputan, a prosperous farming village on the Punjab Plain in Northwest India

Part Three: Jats And Harijans:

The Bullock Cart Race

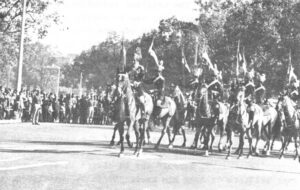

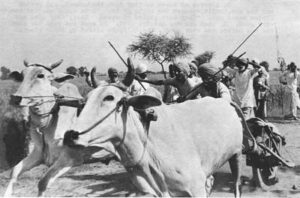

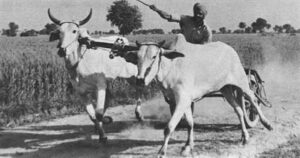

On the afternoon of 12th April, a day before Baisaki, when the harvest traditionally began, the Jats invited farmers from all the neighboring villages to compete in a bullock cart race, the first ever held in Ghungrali.

The invitation had gone oat before the Jats had declared their boycott of the Harijans and banned them from their fields and the Harijans had retaliated by threatening to help no Jat with his harvest, at whatever terms. And so there was uneasiness that there might be trouble when everyone started drinking and crowding together to watch the race. But no one need to have worried; both the Jats and Harijans were relieved at the chance to enjoy themselves and forget, for a moment, the hard labor of the harvest to come and the gathering tension in the village.

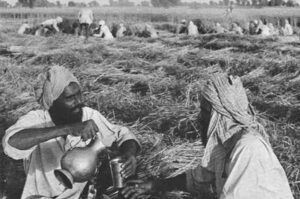

It was a splendid day, the wheat had ripened into a burnt gold and the oats too were ripe and shone in the sunshine like mother-of-pearl; the sky was a pale blue, there was dust and it made a white mist among the trees in the far distance and as the hot breeze came up in sudden gusts, little whirlwinds twirled through the ripe wheat. But no one had watered for some days now and there was no longer fear of the wheat lodging before it was cut.

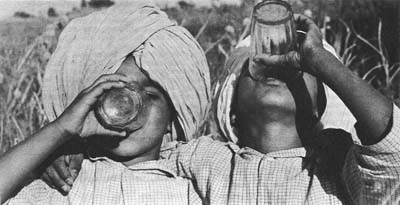

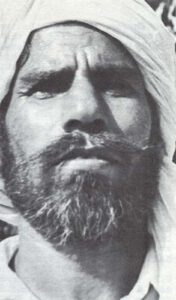

At the well of Sarvan Singh, Charan’s uncle, there was a festive air. Sindar, the cheerful braggart, had been goaded by his cousin, Dhakel, and Gurmel, the Harijan sharecropper, into entering the race and he fussed about importantly, washing and brushing down the bullocks and talking incessantly to his cousin, who sat hunched over their, irrigation ditch, cooling some bottles of homemade liquor to drink that afternoon. The son threatened to be as scorching as on previous days but the air was not yet suffocating and water gushed from the tube well, looking maddeningly inviting. Gurmel’s two little boys, Ranjit and Surindar, sat hunched and laughing on the bank, watching Dhakel and wearing the pale pink and yellow turbans the men had brought to wear to the race.

“See, O, Deaf Man,” laughed Dhakel, pouring each of the boys a tiny drop in the bottom of a glass, “they are drunkards like their father already.”

“O, today, you shall ran like the wind,” Sindar told the bullocks. “Stop, O, Balda, why are you dancing so? Stand still. Pour me a little, Dhakel. If you take a little now you’ll get yourself warmed up for the whole day and you won’t need more.”

Dhakel poured them each a glass, which they swallowed in a single gulp each. “Ah.” Dhakel smacked his lips and wiped his moustaches. “It’s all right. It will serve our purpose. We don’t have to spend money.”

“Ah, yes, the price of a bottle has now gone up to ten rupees since the first of April.”

“Leave the rest in water,” advised Gurmel. “It will get cool. Now there is a brim. That’s a sign of good liquor.”

“Hm-m-m-m.” Dhakel had poured himself another half a glass.

“Now the dove is cooing,” said Sindar. “It means that it will be a very hot afternoon. For eight or nine acres you don’t know where the cart goes. It’s a very good cart we have. And today you’ll see them falling in the ditches.”

“You’ll break your leg,” chuckled Dhakel.

“When you have to fight a battle, why worry about your legs and arms,” declared Sindar grandly. “We have so many entries from our village. I don’t know about the others. But in this village, no one can beat me. “

A crow squawked noisily in the oak branches, as if it had been eavesdropping. “Kill that bastard,” Sindar cursed. “I’ll rape his mother.”

“Just hit him with a big stone,” said Dhakel. “Then he’ll understand.”

“Better you go home and rest,” Gurmel suggested.

“O, Deaf Man, what should I do there? Should I grab someone’s penis? We’ll go straight to the race. Come and start the engine. Let’s get the fodder cut.”

“Wait,” said Dhakel, “here comes father with food.”

“Ask Lanedar,” said Gurmel, using the respectful Punjabi title for the head of the family, “how many carts have reached the village.”

“O, there are many,” Sarvan said, unwrapping the chapattis and curry from a cloth. “Where did you bring those bottles from?”

“They have come up from the earth,” laughed Gurmel.

“Now it’s time,” said Sindar. “You finish taking food and then we’ll get going to the race.”

“O, it doesn’t start for three more hours,” Sarvan said. “Even then they will first put all the entires into a jug and they’ll pick them out one by one to see who goes first.”

“That’s good, that arrangement,” Sindar approved. “Some of the people will want to put themselves at the top of the list.”

“There’s a lot of entries, I have heard,” said Sarvan.

“O, then why should we kill our animals and play hell with them,” said Sindar, suddenly feeling very concerned about the bullocks.

“The first prize will be sixteen kilos of ghee, with eight kilos to the second man.” Sarvan looked into the ditch. “What will you do with all these bottles?”

“They’ll go in our bellies,” laughed Dhakel. “Nobody will be able to find them there.”

“Have you used all the sugar that was left?”

“No, just to serve the purpose for today only. If we get time we shall finish all four jars in the evening to have plenty for the harvest.”

“You shouldn’t leave them lying there like that for long.”

“O, Deaf Man, if you’re strong these days with all the Harijans on strike it will be good,” called Sindar.

“I would be with them if I wasn’t a sharecropper,” said Gurmel. “Only the daily wage laborers are taking part in the boycott.”

“When I was young,” Sindar went on, “they used to feed as with mustard oil. It makes your limbs strong.”

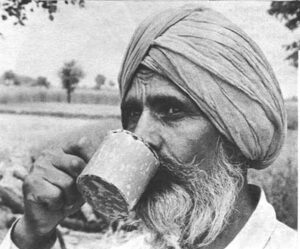

Sarvan poured some of the liquor into a mug and tasted it.

“O, you must not eat mustard oil during harvesting; it makes your limbs soft,” he said.

“If you feed bullocks full they can really run,” said Sindar.

“Yes, mustard oil makes your limbs supple, but you lose vitality.”

“No.” said Sarvan. “You most not feed the bullocks mustard oil too long.”

“I want some mint,” one of Gurmel’s little boys suddenly announced.

“What happened with you,” said his father. “You were playing here since morning and now you want to give birth to a child.”

“I want some mint!” the little boy demanded. Sarvan took the boy by the shoulder and went to the mint patch with him as Gurmel and Sindar pat the bullocks under the yoke.

“Why don’t you come and have food?” Dhakel called to Sindar.

“I told you, I wouldn’t eat today.” Sindar took a deep breath and held out his chest. “Ah, today, I shall crash someone under the hooves of my bullocks. I shall ride them across the wheat fields like the wind.”

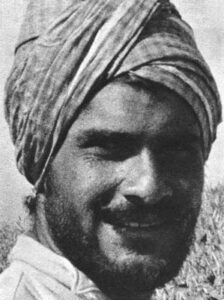

By three o’clock, when old Sarvan joined a group of men at the starting gate, the dirt road past Basant Singh’s lands on the northeast corner of Ghungrali was lined with hundreds of men and boys and the race was just about to begin. The sun was scorching, a gray haze of dust hung over the road as the carts drove back and forth on practice runs to show the bullocks the course and a hot wind stirred the ripe wheat and raised swirls of white dust. The sun looked almost white and in the luminescent light, everything was a beautiful pastel color: the wheat, the sky, the trees, the men in their white shirts and colored turbans, yellow, pink, pale green and lavender. “Clear the way! The first is coming now!” rose the shouts. “O, come with pomp and show,” shouted the starter. “Come with courage. Come, O, Bhajan Singh of Mal Majra, come!” And in a great cloud of dust and a pounding of hooves and snorts and shouts, the first cart passed down the eleven-acre course. “Have you seen that bullock cart going at forty-two knots,” an excited man shouted to his neighbor. Prit, Charan’s handsome young friend who was to race later, came along the road, calling out, “O my brethren. O, fellow men of my village, go and pass the word and tell people, O brethren, my sweet and nice people, go and tell the people they shouldn’t rain the farm of some poor brother.” “We’ll announce it over the loud speaker at the starting gate,” Sarvan called to him.

At the starting line, the second entry was having trouble controlling his bullocks, who snorting and jittery, wanted to rush forward away from his place. “Hold them!” shouted the starter. “We’ll scratch your entry if you cross this line before the flag falls.”

“Go that side,” Sarvan shouted at two boys. ” Don’t stand here.” “I won’t put my bullocks into the yoke until the way is cleared,” called the third entry, a tall, stout man all in white. “Why are you standing there?” Sarvan called to men stepping into the road. “Move one way or another. Get back! Get back!” At the finish line, an announcer called over a loudspeaker: “Bhajan Singh of Mal Majra. One minute and sixteen seconds!” There were cheers up and down the line. “Next entry. Mehar Singh of Bhambadi!” called the starter. “Now, please, come, come, come. The flag is waiting to come down! “He’s off! “Ha la! La la la!” “O, fools, now you be strong. O, no, they ran before the flag was down! Scratch that team. O, give those boys one slap each on the back of their necks: Why are they blocking the way?” The starter seemed to run around in circles, beside himself, “They must have given something to their bullocks,” called a man. “All the good bullocks are dead drunk,” cried another.

In a grove of trees halfway down the course, old Pritam and his son, Surjit watched the carts go by. “Here comes another one,” Pritam would say. “They have picked up speed. Look, they also are very good. O, that one was not too good. He used the pins too much. The one before was very good. The bullocks picked up their stamina and ran. You only enjoy the bullocks running when they’re brave.”

“Some persons wreck their game by using pins,” Surjit would answer. “Now keep watching, father. See how much time they take. They’re only two in competition so far, the first man and the cart from Bhambadi.”

“But where are the young men from our village?” Pritam asked. “Young Prit has already taken his bullocks to the starting line but I have not yet seen our Sindar go by. O, there’s Dhakel on a bicycle. Perhaps he is looking for him.”

Ahead on the course, Charan and his friends, who had been drinking since noon, roared with laughter as a drunken, red-faced man in a black turban came staggering down the track, waving his arms and shouting, “For God’s sake, please clear the way. You are masters of your own wills. It is your village. But clear the way.”

“That last was very fast,” said Kaka Singh, the Bandit. “That driver was the same as for another cart. He is damn good.”

“Don’t worry. A Ghungrali wallah will win in the next round,” said another crony. “Look, the flag is up again.”

“It’s Avtar,” said Charan I recognizing a neighbor.

“Avtar’s bullocks will take minutes, not seconds,” said the Sarpanch. “Don’t think that they are the best. O, clear the way on that side, you little children, or ask your fathers to join the race.”

“That Isaru wallah got his bullocks too drunk,” said the Bandit. “That’s the sort of people they are. They worry about winning instead of enjoying the sport.”

“O, children, get out of the way, O, children!”

“One minute sixteen seconds is still the best time so far!”

“Come, Charan, let’s slip behind those trees and have another bottle. This will go on all afternoon.”

Over their voices came the sound of a loudspeaker from the top of a parked truck at the finish line. “Bring that red flag up, just watch the red flag,” it called. “These bullocks are running eleven acres. That is something. Run, go! Shabash, shabash. O, green and red turbans, please clear the track. Mukhtar Singh of Jarg. One minute and twenty-nine seconds. O, get down children. Now it’s number twelve, Ajit Singh of Majari. Shabash, shaba-a-a-ash!” One minute, seventeen, ties for second place so far today, all dear friends. We have two stopwatches here. Look at your watches, judges. It all depends on what you feed your bullocks, my good friends. Ghee and good grains. Look how the bullocks come. Shabash, shaba-a-a-a-ash! Like air. Look with your fall eyes wide open but clear the way, my friends. Slow! One minute and forty-five seconds. Anybody who wants to race can still come and pay his ten rupees. You must take care of your bullocks, friends, feed them. Spend good money on your bullocks and you’ll get good results and honor too. Can somebody serve as water up here as a social service to his friends. Come forward, O, waterman. Now, Sardar Sahib, take the flags up. He’s an old army officer and knows how. You can kill a battalion for one flag. Shabash. Sh-a-a-a-ba-a-a-sh.

“Just watch. Watch for the flag. The red flag will come up, the white flag will go down and they’ll start running. Now Mohinder Singh of Isaru. Bring the flag up, brother. O, red flag people. Watch out for the flag. Mohinder Singh’s cart is flying. That’s how he runs. That’s how the flag goes down. Shabash, shabash. What’s the time? Its one minute, twenty-two-point-eight seconds. Gurbach Singh of Ghungrali is coming. Away. Push away that cycle. Gurbach Singh is coming. What? He’s running like a railway train. O, you. One minute, twenty-four seconds. Shabash. Now watch the flag. It’s Darshan Singh of Rajewal. See how he comes!”

“Darshan Singh of Rajewal at one minute twenty-nine seconds,” the voice of the announcer went on. “Look at that man over there. He’s making mischief. O, black turbaned man, don’t make mischief. Stand apart, stand apart. You must stand out of the way, my brethren. People are standing in the way. Please, number-seventeen. The flag is up! The cart is coming at fall speed. Watch out with patience and wide eyes and see with pleasure but stay out of the way. And now Pritam Singh of Ghungrali. Shabash, shabaa-a-ash! One minute twenty-nine seconds. Pritam Singh of Ghungrali. We’ll shout with great applause and the winners will take their awards, ha, ha, ha, A-ha, hat ha. Shabash, Jugendar Singh of Rauni. One minute and thirty-four-point-eight seconds. And now comes on line – who is it? – Harcharan Singh of Monepur. We don’t have to hide anything. Everything will be before you. What has happened? The flag is down. The cart is coming. It’s Harcharan Singh, Monepur wallah. Shabash, Harcharan Singh of Monepur at one minute thirty-one seconds. Who’s next? Surindar Singh of Ghungrali. Come on, Sindar! Friends, clear the way, Sindar Singh, Ghungrali wallah is coming. See how he flies!…

…Oop! What’s happened? Friends, clear the way so we can see! Stop running this way and that! Ah, the bullocks are running towards Bhambadi into the wheat field. What? Friends, clear the way! We can’t see! What, has happened to Sindar? O, he’s turned them around. O, they’re back on the road again. Clear the way, clear the way! Friends, the cart is coming, Sindar Singh, Ghungraliwallah. Clear the way. The bullocks are coming with great dignity. Don’t worry, they’ll reach here some day. Now they’re back on the road and the cart is coming. Shabash, Shaba-a-a-a-a-ash, Sindar Singh of Ghungrali!” And a great roar of laughter came up from the crowd. “Time, what is the time?” voices shouted. “Two minutes and five seconds. Sindar Singh, Ghungraliwallah, two minutes and five seconds.”

“O, no!” “Poor Sindar.” “It is the slowest, time of the day!”

Charan and his friends, seeing Sindar was not hurt when his bullocks turned and ran into the fields, whirled around and got back on the road, laughed and laughed. Charan shouted, “After seeing Sindar who needs a bottle to get drunk?” and he almost doubled up with laughter, slapping his thighs and rocking back and forth.

Charan and his friends, seeing Sindar was not hurt when his bullocks turned and ran into the fields, whirled around and got back on the road, laughed and laughed. Charan shouted, “After seeing Sindar who needs a bottle to get drunk?” and he almost doubled up with laughter, slapping his thighs and rocking back and forth.

There were half-a-dozen more entries before the prizes were awarded. The announcer shouted, “The winners are Bhajan Singh of Mal Majra, one minute and sixteen seconds, Ajit Singh of Urna and Arjan Singh, Rampurwala, tied for second place….” A great round of applause and cheers rose from the crowd. “Now we must thank these sons of the sacred cow, our bullocks. The great Maharaj will help them in the future too. We thank all those who have participated and who have come and we’ll have every year from now on. Good brethren….” Charan looked to see if Sindar was with the entries at the judge’s stand. But Sindar had disappeared….

The next day, braiding ropes for the harvest under the shade of the big banyan tree, Charan shouted to Sindar, who was working with Gurmel, “Hey, Sindar, how was your bullock cart yesterday?”

Gurmel, who held onto one end of the reed rope and stepped back as Sindar braided the strands, laughed. “I heard you, were ill.”

“No,” Charan chuckled, “he got frightened like his bullocks to see the crowd.”

“Now we’ll have races again without the crowds around ” Sindar replied wearily. His head ached from finishing two bottles after the race the night before. Following his humiliation, he had driven straight for the well in the fields, and was just starting on the second bottle and beginning to feel better when Dhakel and Gurmel came to pick up fodder.

“My best timing on that road before was one minute and fifteen seconds, a second before that Bhajan Singh of Mal Majra who won.” Sindar told them, when they found him sprawling on a charpoy under the oak trees.

“Why don’t you put fodder for the bullocks?” Dhakel asked. “What sin have these poor things done?”

“The bigger one got scared because people were in the way.” Sindar went on, not listening. “If they had just stood on both sides and watched quietly, we would have got the prize, by God. Those bullocks that came in first, I can beat those husbands of their sisters. I used to do eleven acres in one minute fifteen seconds. Now my bullock is too young to know people with different colored turbans and they got frightened. One person threw a bicycle out just to distract the bullocks’ attention. Next year I’ll win. My bollocks will talk to the winds. I’ll take them to two or three races more – to get used to crowds. Next year either we’ll deploy the police or if anybody gets in the road, we’ll use gandasas and behead them.”

“Why did you go to the starting line so late? We thought you mast have got drunk.”

“I deliberately stayed back because if you take the bullocks a couple of hours before the race, they won’t ran. If you take the cart a few minutes before, the bullocks run faster. Some people poor half a bottle of liquor in their bullocks’ stomachs and then he gets brave. He doesn’t get frightened. I was sure that my bullocks weren’t frightened; that I’d stand first.” Sindar poured another glass and gulped it down. “The fault lies with those bastards. Those who blocked the way. Those seeds of a dog, penis of the great God, I’ll rape their mothers!”

Sindar stood up and staggered over to the well to help Gurmel lift a bale to his head. Gurmel motioned him to stay back. “Lie down, I can handle these oats with Dhakel. You, take your rest.”

Sindar ignored him and grasped the other corner of the bale, helping Gurmel to balance it, and cursing all the while, “What shall I be doing all this time? Lying on the charpoy and scratching my testicles?”

“What is tattooed above your knee?” Gurmel asked. “The goddess Chandi?”

“Yes, Chandi helps me everywhere.”

“She didn’t do much this afternoon. Maybe you should have had it tattooed higher.” Gurmel laughed and the two of them went to lift another bale. “If I asked your opinion where to get it tattooed, I’d probably have it right on my penis. Then I could screw you with the help of Mata Chandhi. Here, take that corner. Up, that’s it.”

“All right, I will. But take care of your penis. Chandi Devi might affect it in a bad way.” Gurmel pat his hand to his chin. “O, I have a pain in one of my teeth. “

“I have a wrench,” Sindar said, “If you like I can pull it out.”

“No, God bless you and your tools. Try your hand on someone else instead of me.”

“Once I got a toothache and I went to one doctor in Ludhiana. He broke my tooth, that dentist, I rape his mother. O, I was yelling. O, save me! Don’t kill me, my father. But after that he paid me a fiver to take a glass of milk.” Sindar chuckled. “But you know what I did? I bought a bottle instead. I raped my tooth after getting drunk and did not feel any pain that night. But, O, the next day it was terrible. I had to buy some liquor again to subside the pain. I had to buy some liquor again to make the pain go away. I suggest to you, never go to these dentists, they are real husbands of their sisters.”

Gurmel winked to Dhakel, who was pouring a round from the second bottle. Sindar was back to normal.

Now, under the banyan tree, Charan said in a kindly manner, “At least today you’re up and moving around in the streets. But if you had really lost the game, you’d be in bed the rest of your life. I would feel scared racing a bullock cart. If somebody else is driving then the control is in his hands. If Sindar or anybody asks me to drive with them, I won’t.”

“O, Shabash, Deaf Man, move back quickly, “Sindar called to Gurmel.. “Best of all. Go back, go back. We’ll be through in half of the time Charan is taking. Nobody dares beat us.”

“Nobody dares beat you in bullock races also,” called Scooter, who was holding the other end of Charan’s rope.

“Our game was wrong. The people frightened as. Those Ghazipurwallahs. They kept standing in the road.”

“Sindar has been having diarrhea all day because he lost,” Scooter laughed.

“Why should I have diarrhea?”

Charan laughed. “Seeing you race, I got so drunk I didn’t need any more liquor.”

“Even if my bullock cart falls in a well I won’t have diarrhea.”

“If you told as before,” Charan said, “and we’d treated you with liquor you would have won.”

“What way was your cart going? To Bhambadi?” Scooter laughed.

“Our cart came straight.”

“That’s why you took two minutes, five seconds.”

“In the evening, I’ll show you I can come in one minute and fifteen seconds. I can show you today. It I take twenty seconds I’m ready to buy you a bottle of wine.”

“At that time you will have your own watch. It makes a difference.”

“We should have given a prize to the man who came in last,” the Sarpanch called, approaching along the road.

“A Harijan can make a child in two minutes, five seconds.” joked Gurmel.

“There goes Prit. Hey, Prit!” the Sarpanch called. Prit came up on his cycle from the road, west.

“We have given a good name to your village,” he said apologetically, putting down his cycle and coming to shake hands with the Sarpanch and Charan.

“Yes,” laughed the Sarpanch. “Sindar really did. We just wanted to show those outsiders we had a bullock cart in Ghungrali. We didn’t mean we wanted to race it.” Everyone laughed. “Move back, move back.” Sindar called to Gurmel irritably, pretending to be absorbed in his work and not listening.

“I told Dhakel we could make a good pair,” the handsome Prit went on. “One good bullock is with them and one with me.”

“You know bullocks are sometimes in the habit of running into fields.” Sindar said, half-heartedly. Prit ignored Sindar. “I have one really good bullock,” he told the Sarpanch. “You can try him with a cycle if you like. He’ll run alongside a cycle for two miles.”

“Bring a bottle and we’ll take a bet now.”

“It’s difficult to make eleven acres in a minute, fifteen seconds,” Prit continued. “I can do it in a minute, twenty. Bhajan Singh’s bullocks were too eager to run. They couldn’t even wait until the black flag was down. We had them go back again. In the meantime, one person from Majari, he was dead drunk, he came and pulled their bit. Ultimately, we had to throw that man out. But the Rampuria wallah had the best bullocks. They must have won if it was a short sprint. Those others could run for miles together. They only did one twenty-two but they are really good-on sprints.” Prit spoke with brisk assurance.

“We had hopes that your bullocks would stand first,” said Gurmel, slyly.

“You’re a fool. I had only one good bullock. I took a minute twenty-nine seconds. My feeling is never touch your bullocks and you’ll run better. I’ll stand first one time without beating them, one drunken man yesterday gave a half bottle to each of his bullocks. He made a mess out of a real pair of bullocks by giving them liquor.”

“Your bullock was running toward your own well,” muttered Sindar.

Prit again ignored him. In fifty-two seconds, I can cross eight acres but the last three take a lot of time. Today is a good day. It’s a fine day and it’s better we take some bet. We could arrange to drink together.”

Charan laughed but said he had to make ropes for baling.

“We’ll start making ropes tomorrow,” Prit said. “The wheat should be a little green; it shouldn’t be overripe. Now a lot needs cutting but who is to cut it? The Harijans are bent on teaching the Jats a lesson and they will. We’re going to wait for two days more to start reaping. The best way is that we should switch to the old system. If your wheat is ready, everybody should come out and cut and then the next and next. I’m ready to throw a big feast if everybody comes out and cuts mine. But, on the other hand, it this boycott isn’t settled and we calculate at the end, I bet we’ll save at least a lakh of rupees in the village.”

“You don’t know,” muttered Sindar under his breath and braiding the reeds more vigorously than ever. “God will rain this village because you’re really hurting the poor.”

“Where will you get your laborers, Prit?” Charan asked.

“I don’t know,” answered the other, moving off on his bicycle. “Tomorrow we’re going to other villages to hunt for some.”

There was silence for some minutes as Charan and Sindar settled down to braiding. Then One-Eye came by on the road from the village and took a place under the banyan tree to watch them working.*

“Do you know how far things are going?” One-Eye said after a pause, in his whiny, obsequious voice. “Do you know, Charanji, that today they stopped cleaning Basant Singh’s barn, these Harijans. Tomorrow they’ll stop cleaning all the others if this keeps on.”

“It doesn’t matter,” Sindar, who disliked One-Eye, said cheerily. “The Jats should install underground drainage anyway. You can have manure pouring right into the fields. The Jats can: dig deep ditches and when their cows and buffaloes want to piss, they can just lead them to a ditch.” Sindar chuckled.

“You brag too much and you were the last in the races yesterday,” hissed One-Eye.

Sindar’s smile died and he did not speak again until One-Eye had gone away. Then with a grin he called to Gurmel, “O, shabash, Deaf Man. Beat all of them. Go ahead, get back, get back. We’ll beat them all. I’ll see to it.”

“That One-Eye,” Gurmel called back. “His father must have had his mother at some odd time and he’s the seed of that. He’s like a mad dog. If he sends his wife to my father, only then will he get. a child. The impotent bastard. That’s why he abuses people, He will be worst hit by the boycott. He has the worst crop in the village. A real weed patch.”

* As the poorest Jet in Ghungrali, Mohinder Singh (One-Eye) had only four acres and hence, much free time.

Charan turned and looked down the road at Gurmel, the anger in his outburst taking him by surprise.

The Boycott

Cruelties of Landlords Against Untouchables in Village Near Ludhiana

Orders of Inquiry from Deputy Commissioner

Believed to Have Been Lost at the Police Station

April 16 – In Village Ghungrali-Rajputan, near Khanna, the Harijans are being cruelly mistreated by the landlords. The samidars have totally blocked the women of the Harijans inside their houses. Harijan women, young girls and children are sitting inside the four walls of their little houses and have dug small ditches for answering the call of nature in their own courtyards. They are not allowed to move outside in the streets and the fields. In the village there are about 125 Harijan families and 60 landlords. During the last harvesting Harijans were compelled to take minimum wages and work for cutting their crops and threshing their crops. On these wages they cannot meet their ends.

But this year, the landlords have imposed another cat in daily wages. When the Harijans refused to accept such a meager amount, the landlords totally boycotted them. The panchayat of Ghungrali has appointed a 13-member committee which always goes on imposing such new orders so that if any Harijan tries to lift his head a little he will be totally boycotted. The Harijan’s deputation from this village met the Deputy Commissioner in Ludiana who ordered the officer in charge of the police station in the nearby town of Khanna to go to Ghungrali and inquire into the matter. But today, six days have passed. And orders of the Deputy Commissioner were lost in the police station. And Harijans of this village go on leading a miserable existence. Even the Akali Harijan member of the Legislative Assembly in Chandigahr seems unable to do anything to alleviate these cruelties against the Harijans.

(DAILY HIND SAMACHAR, April 18, 1970, page four)

This newspaper story, which appeared in organ of the Hindu right wing in the Punjabi city of Jullunder, was the first sign the trouble in Ghungrali was getting outside attention. The newspaper was notorious for its position that Chamars and Mazhbis were not really Sikhs but Hindus, which if accepted in every village in Punjab would have given the Hindu minority control of the state government. But the story, as it appeared, was a mixture of truths, half-truths, distortions and outright falsehoods and was, in the main, not true. Nor was a second story, which appeared a few days later, presumably planted by the local authorities, reporting that the boycott had been settled and normalcy restored to Ghungrali.

In actuality, Harijans were not prevented from entering the fields of the Jats except for the purpose of weeding and gathering fodder and no one, man, woman or child, had been confined to his house. What had happened were two very minor incidents.

A Jet youth named Baj had called out tauntingly, or perhaps jokingly, to a Harijan passing under the banyan tree, “0, you’re walking on the road!” And a Harijan youth, Zhora, was relieving himself in a wheat field when the owner’s son, a classmate at school, shouted, again perhaps as a joke, “Hey, Zhora, you get up! You can’t use my fields for answering the call of nature.”

Gurdial Singh, the Chamar who had prospered with his poultry farm and was asserting himself as the leader of the Harijans, seized on these incidents to involve the police as the local representative of an Indian Government, constitutionally committed to ending untouchability and all forms of caste discrimination. Gurdial’s strategy, was in making it seem to appear that the Jats had infringed on the civil liberties of the Harijans in Ghungrali whereas the real issue was the survival of the village’s traditional social structure during the transition from the traditional jajmani system to a modern money, economy, a process accelerated beyond anyone’s expectation by the new high-yielding varieties of wheat.

Hence, Gurdial, with the help of a lawyer in the next town, drew up charges the Jats of Ghungrali had been “insulting women…not allowing Harijans in the fields to answer the call of nature and not allowing Harijans to enter their fields or enter country roads and lanes for the purpose of grazing.” Gurdial’s intention was to turn an economic confrontation into a legal one in which the law was clearly weighted in the Harijans’ favor. It was he who had also sent the story to the Daily Hind Samachar‘s local correspondent. The government of India was also considering direct village elections for the office of village chief or sarpanch, who was presently elected by the five-member village council or panchayat, who themselves were chosen by direct ballot. Many of the Jats believed Gurdial sought to polarize the village along caste lines with the aim of being elected sarpanch himself. Indeed, after reading the first newspaper story, Pritam. Singh, the current Sarpanch, commented, “Now the Harijans are in Gurdial’s hand. Once they fall apart he’ll lose them. I’m still trying to bring in a neutral Mazhbi who can talk to them and get them to arrive at a reasonable position for reaping the harvest. Then I’ll compel the Jats to compromise.”

Events, however, were moving on and the positions of both the Jats and Chamars were hardening with the relatively small group of Mazhbis still undecided whether to join their fellow Harijans in the boycott. By the eve of Baisaki, some 52 Chamars who earned their living were directly affected by the boycott and had no work. If one included Chamars who made their living through poultry or dairy operations and who had depended on the Jats for fodder and the year’s wheat supply obtained in a week or two’s reaping and threshing, and the wives and children of all these men as well, then a good half of the village’s population was suffering economically.

The Chamars, under Gurdial’s leadership, themselves formed a 13-member committee as a counterpart to that of the Jats and since Mukhtar was the leader of one of the village’s four Chamar factions, he was asked to join although he opposed the boycott and questioned Gurdial’s leadership. This committee then decided that any Chamar who broke the boycott and labored for a Jat during the harvest would be fined-fifty to one hundred rupees in cash and prepare free rice for the entire Harijan community, which meant economic rain for the poorest of them.

On the Jats side, old factional struggles were shelved and Ghungrali’s four Jat factions, those of ancestry from Bija, Jabbadi or Mehndipur villages and the fourth hodge-podge group, unified for the first time in many months. But clear divisions of opinion still lingered.

Basant Singh, with his overriding interest in economy of operations and returns, and perhaps seeing a chance to embarrass the Sarpanch’s rival faction, took the hardest line from the first. “The Harijans are plainly in the wrong,” he declared. “For the past two years the Jats have been suffering a loss, giving them fifty to eighty kilos of grains per acre. We’re not going to repeat that ever. These laborers have progressed more rapidly than the small cultivators. That’s why they’re complaining so. They’ve had a taste of prosperity and they want more. Well, they’re not going to get it. The main issue is that since all over Ludhiana district the going rate is for Harijans to take the 35th to 40th bale of every field harvested, we’re being generous in deciding on the 30th bale.”

Charan knew this to be untrue. When the boycott first started he asked the village electrician, who was a Hindu who lived in Ghungrali but served the government in five surrounding villages, what was that year’s rate elsewhere. The Hindu had told him, “In no other village around here are the Jats trying to get a fixed general rate like this 13-member committee here in Ghungrali. Since the trouble started I make it a point to ask people, “What rate will you pay?” In all the villages the rate went from the 15thto 30th bale, negotiated individually between each Jat and the Harijans themselves. Most other villagers know about this trouble and seem to be of the opinion that if the Jats and Harijans reach a settlement soon it will be good before the trouble spreads.”

“What we have sown, we will reap also,” said old Pritam, who opposed the boycott but respected the Jat committee’s authority.

“We didn’t pat those seeds in the earth, thinking some Harijan’s name was written on it to cat and reap,” said Sarvan.

Surjit Singh, the former sarpanch, stood staunchly by Basant Singh. “Either we shift to machinery or get labor from outside,” he said. “It’s the only solution. We had a bad experience giving grains last year and we don’t want to repeat it. The Sarpanch says, “I won’t intervene.’ He has no real guts. After the Harijans didn’t answer our request for a meeting to discuss working on the 30th bale, we proclaimed, ‘You are banned from our fields.’ Two unrepresentative Chamars came to see me and one, that Teja Singh who always speaks in such inflammable tones, told me, “Look, if you give as labor on even the 10th bale, we won’t accept it from you now. You just bring your bombs and drop on our houses.’ Those Chamars who have no relation to the farmers except for taking weeds and grass from their fields are the real troublemakers. Gurdial is aloof; he’s not a troublemaker. I feel strongly that this boycott will be harmful to the village. But the poor are making more money than ever and spending it on narcotics, liquor and tobacco. Their real enemies are their bad habits. In our villages, Harijans do better than the small farmers.”

Some of the Jats felt like Charan’s father, old Sadhu Singh, who said, “Among the Jats, the real dahulis,” he used the Punjabi word for foolish wastrels and troublemakers, “are those who have small land holdings like One-Eye who can cat his grain himself. And from the Harijan side the dahulis are those who have some business of their own like poultry or dairy and don’t depend on daily wages. The whole thing is so much nonsense. But you’ll see. Once the wheat gets too ripe and starts to shatter how the Jats and Harijans will go running to each other!”

On the morning of April 13th, Baisaki, the Jats and Harijans of the village traditionally went to the Gurdwara to pray together for a good harvest. This year the ceremony was held as always but almost no one went, aside from old Chanan the Mazhbi, Sadhu Singh and a few other elderly village traditionalists who always observed the ceremonies. Instead, the Gurdwara ground, on a neem-shaded hill overlooking the whole village surrounding it, had become the center of economic activity. On a terrace toward the back sat the Jats’ 13-member committee while clusters of farmers representing almost all the Jat families of Ghungrali stood around the courtyard or rested under the neem trees. Near the gate, somewhat aloof from the rest, stood Basant Singh, Surjit Singh and some of the village’s richest farmers. They had been waiting for an hour, after sending a messenger to the Harijans, summoning them for discussions.

Now there was a stir, as the village messenger returned from the Harijans quarter and told Basant Singh and the others at the gate, “They were all sitting there and they said, ‘We’ll come some other time, not now.” Then feeling this message seemed rather insignificant for such an important audience, the messenger I an old whiskered man, added, “When I asked them, all four Chamar factions were there, they frightened me with their eyes.” Surjit Singh and his younger brother, Sudagar, a stern, greybeard who was one of the wealthier farmers, relayed this message to the 13-member committee. The messenger, happy to be the center of attention, began gossiping, “I went to Khanna to bring this woman….” After some discussion back and forth, the 13-member committee decided to send three leading Jats to the Harijans to ask, “What is it you want? Why don’t you come?”

This settled, Surjit Singh wandered over to where Charan was sitting with some of his cronies in the shade of a neem tree. “We have decided to try for a settlement this morning,” he told them. “If the Harijans don’t come today, then it’s finished. More than forty-five Jet families of the village are represented here. We told them, ‘You discuss among yourselves but if you want a settlement, come now. If you don’t come now, we’ll never talk.”

When Surjit moved on to inform the other Jats, Sukhdev Singh, a retired sepoy of the Indian army who with his brothers was one of the richest farmers in Ghungrali, told Charan, “This is all village politics. The big ones like Basant Singh don’t want to come in front. Those committee members are dahulis, fools. We’ll need fifty laborers this year. We’ve planted seventy acres of wheat. Don’t think we can afford to rely on these fools. We’re getting men from outside ourselves.”

“I think the Harijans may be waiting for the police,” Charan said. Just then, two Jats returned to the Gurdwara. “They have left their Dharamsala and are moving this way,” they reported. Old Pritam wandered by, looking confused-by it all. “I understand we have been sending them messages since morning,” he said.

The Jats turned to the road. About twenty Harijans were approaching, mostly in the gray and grimy rags they wore for work but a few in white shirts and colored turbans who were hardly indistinguishable from Jets. They assembled in a semi-circle in an open ground by the village dispensary. Basant Singh and the other Jats in the courtyard descended to meet them, but the 13-member committee remained where it was, apparently staying in the background this time. The Jats grouped themselves in a semi-circle facing the Harijans and all the men sat on the ground, only Surgit Singh and his brother, Sudagar, rising as spokesmen. A bareheaded, clean-shaven youth rose to speak for the Harijans.

“Now come forward with your conditions and demands,” Sudagar declared, but his voice was drowned in the sudden chanting of prayers from the Gurdwara’s public address system. “Turn off that loudspeaker,” he snapped with irritation.

Charan noticed that his friend the Sarpanch, although the chosen leader of the village, had stayed away. It seemed to be Basant Singh who was running things, since Surjit and Sudagar were his usual spokesmen in public.

“We want according to the field, that we should be paid for reaping according to the crop of each field,” said the Harijan youth nervously.

“If we do it like that we can’t form a committee to go to each and every field to decide the worth of the crop,” Sudagar said testily.

“We don’t know about everyone’s field, but each Jat knows his own crops,” said the boy.

Surjit intervened, speaking in a calmer and more reasonable tone than his brother. “The Jats want that they should be giving less and less,” he said. “You want more and more. We have to decide where the common area of agreement lies. Traditionally the wheat was cut for the 20th part of the crop. But now new varieties of wheat have been introduced. If you go to Basant Singh’s fields you can cut cheaply because the crop is rich, but those with poorer crops will suffer.”

The Harijan youth did not know what to reply. As he hesitated, Gurdial rose from the back of the Harijan group and came forward to face Surjit, some twenty feet away across the open ground.

“We have thought things over the past three days,” Gurdial said with authority. “We have decided we do not want a fixed rate but to settle field by field, farmer by farmer, as do all the surrounding villages. We can only judge when reaching the field what payment will suit as. Now you can go and decide if that is agreeable to you.”

But instead of moving back for a discussion among the Jats, Sudagar said, with even more testiness than before, “If anybody wants to make trouble, he has no place here. We are here to get a reasonable settlement. We want a generalized rate, which can be adjusted to the field. “

“Some people can be cheated on a field by field basis,” said Surjit, again in a more mollifying tone.

“That depends on the man,” Gurdial replied. “A Jat should think about who he is hiring. This trouble is quite serious for as. You don’t allow as into your fields although Harijans have enjoyed this right in all other Punjabi villages for centuries. You must decide, once and for all. But I suggest you consider the enormous consequences of your actions.”

“If you don’t want to reach any conclusion,” said Sudagar, “well, that’s up to you. You do what you like and we’ll do what we like.”

“You must fix rates according to each men’s field,” said Gurdial. “That is the way it has always been in Punjab.”

“We can’t do that. We only want to fix a generalized rate. Then if it’s a weak or good field, you can work something out between yourselves. I have been authorized by the committee this morning to offer you two rates, one for a good field at the 30th bale and one for a bad field at the 28th bale. An individual rate for each farm would be too much trouble. Too much trouble.”

“It can’t be any more trouble than this village is facing now,” Gurdial went on, his voice betraying an edge for the first time. “We can’t go into your fields. We can’t cut grass for our cows and buffaloes. If you cannot adjust each field separately as was the custom for years past, then we are not willing to accept a generalized rate.”

Sudagar said with finality, “If you are not willing to accept a generalized rate, then there is no reason for farther talk.”

For some moments there was a silence as if no one wanted to speak the words that could mean a final break. And then the gray-bearded Sudagar bowed his turbaned head and raised his hands, palms folded together in the formal Sikh gesture of greeting – or farewell. “It’s all over. Finished,” he declared in a low voice. Now you are free to do what you will and we are free to do what we will. Sat Sri Akal!”

Suddenly the confrontation was over and Jats and Harijans were milling toward the gate or climbing up to the Gurdwara. Charan could not believe they had reached no settlement. Then he saw the Sarpanch standing in the back of the crowd. “The Harijans were very strict,” the Sarpanch said. “But we’ll try to bring them around. I’ll arrange another meeting,”

Surjit Singh came up. “The Jats have decided and we are to tell everyone that they are to hire from outside. The boycott stays. Arrange for workers according to your needs. We cannot depend on these Harijans. The Jats think the police had encouraged them to seek stiff terms. Told them, “O, don’t worry, we’ll settle everything all right. According to your wishes.’ How can you go to 1,500 acres and adjust payment field by field? It’s not practicable.” But Charan remembered that Surjit had told him earlier only some 800 acres were affected by the boycott and that the rest would be cut by sharecroppers or men already arranged from outside. Why hurt the poor of the village this way? But he kept the question to himself.

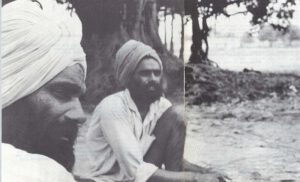

Gurdial returned to the Harijan quarter with the others where a crowd of men had gathered to hear what had happened. He seated himself on a charpoy beneath a banyan tree in an open space where their cattle were tethered and looked around at the anxious faces.

“They want to be dictators,” he said. “But this country is free and we want to live like free men in a free nation. They will not share their prosperity with as if they can help it. We don’t want to commit anything but we were ready to take the 30th bale on a good crop and lesser for a weak crop. We told them we wanted to adjust field by field like they do in all the other villages. But since their 13member committee is there, they said these 13 members can’t go to every field.”

“Those dahulis,” said a man from the crowd. “Opium addicts, drunkards, that one-eyed person, they are an insult to us!”

“What ingratitude!” Gurdial went on. “I went to cat the harvest in recent years not because I needed the money but because some Jat friends would tell me, ‘My crop is going to shatter.’ I left my brother with the poultry farm and took the members of my family to the fields, as you all know. We earned some grains and kept our friendship with the Jats by helping friends in need.”

“What can we do now?” asked a man.

“We have decided that anybody who wants to help any Jat can do so, at whatever rate he wants. The only condition is that this Jat must open the boycott. He must declare his field is open to all Harijans. If this happens the boycott is automatically broken. Now, the Jats didn’t come to terms this morning. Collectively, nothing is solved. Individually, you are free to do what you want. They asked us, they made a demand, for a generalized rate, with 30th bale for a good crop and 28th for a bad one. But a Jat with a bad crop, he will say, ‘Mine is A-1.’ So what kind of a solution is that?

“Why is a fixed rate bad? Because if tomorrow the price of wheat rises or drops, we’re stock at a fixed rate. Even if they offer as the old 20th part, we won’t fix a permanent rate.”

Just then, Kaka Singh, the Bandit, who seemed a little drunk, came striding up to the Harijans. The crowd parted and he advanced to Gurdial, greeting him and the others, “Sat Sri Akal.” Then the Bandit turned and faced the men, and weaving a little, declared in a load voice, “Come and cut my wheat! You are allowed in my fields. I have seven acres of wheat and one acre of jowar. Who wants to come? I damn this village and the Jats’ decision!”

When the cheering died down, Gurdial hastened to speak, “Even if Kaka Singh needs only one person he can take from as. But he mast declare over the Gurdwara loudspeaker, ‘I won’t stop any Harijan from coming into my fields.’ If any Harijan goes to a Jat without satisfying this condition* that the Jat publicly declares all Harijans can enter his fields, that that Harijan will be punished.”

At this the meeting broke up and the Bandit was left to scratch his head and wonder if he would get some workers after all. For he had not entered the Gurdwara since his release from prison two years before.

Meanwhile, as Gurdial was speaking, Basant Singh, rifle over his shoulder, met old Marata, his Mazhbi laborer of many years, on the road to his farm.

“Why are you wandering around so?” Basant Singh asked the old man. “I want you to go and help make ropes for the harvest.”

“When this boycott is over, then I’ll come to you and make ropes,” Marata replied. “We are on boycott.”

“We haven’t boycotted the Mazhbis, only the Chamars.”

“We are with our brethren, our fellow Harijans,” the old man maid with dignity.

At that Basant Singh lost his temper. “Where are you coming from?”

“From the melon patch you gave me.”

“Aha! So your community won’t boycott you for watering your melons on my land,” fumed Basant Singh.

“What do you mean?” Marata asked. “You want to eat up my labor when I have sown, ploughed and labored over that melon patch all year?”

“Don’t get funny with me,” Basant Singh-growled. “Or I’ll throw you out. I’ll throw you out of my fields, you black seed of a dog. I’ll put my penis in your daughter. I’ll rape your mother.”

“I won’t pocket this insult, Sardarji,” the old man shouted and ran down the road. Within an hour the episode was all over the village. Charan, meeting Basant Singh later, asked for his version. They encountered each other by accident in the village and Charan slyly said, “What happened with Marata? I heard something.”

“You know he was playing funny,” Basant Singh said. “I told him to make ropes. He said, ‘If I make ropes my community will boycott me.’ I wanted to tease him. I said, ‘Won’t your community boycott you for watering your melons in my fields? If you want, to save your prestige, I can water your melon patch also.’ I said this tauntingly. At this he jumped right oat of his clothes and yelled, ‘Well, now, you want to eat up my labor which I earned and you don’t want to give me that melon patch that I was plowing and sowing and earning?” And I told him I didn’t mean that and again he was funny. ‘What else then did you mean?’ At this point, I lost my temper and said, ‘If you play up things like this, you, my brother-in-law, I’ll throw you out. And I can physically drag you from my fields if you talk like this, don’t think I can’t.”

Charan, who knew the true version since the fight had been overheard by some Jats working in the fields, was slyly sympathetic. “You didn’t really abuse him. Brother-in-law is nothing. It doesn’t necessarily mean you have slept with his sister. The foolish man didn’t understand you were being friendly, that’s all.”

“I know he was just playing up to his community,” Basant Singh snapped and marched on. But in the Harijan quarter, where Marata was one of the most respected and saintly men, there was real anger. “Marata’s a poor man and he’s hardworking,” said Sher. “Why should he be insulted like that? He’s a poor Mazhbi and Basant Singh knows he can’t hit back or would never abuse him. That’s why he picked on Marata and Marata had to pocket the insult. Basant Singh would never abuse some really strong person; he’s a cowardly bastard without that rifle.” From then on none of the Mazhbis would clean Basant Singh’s barn.

Without the Chamars and with the Mazhbis still hanging in doubt after this incident, the Jats informed the 13-member committee they would need at least three hundred laborers within the next day or two and it was decided to try and obtain them from the town of Saharanpur in neighboring Uttar Pradesh state where the harvesting was already completed.

The committee members were sent around to inform all the Jats and Sarvan, coming to tell his older brother, found Sadhu Singh at the cattle barn, enjoying a leisurely bath. Sadhu was seated with only a towel wrapped around his large stomach and was pouring hot water over his shoulders and head from a silver vessel before sudsing down.

“We have decided to send two or three persons to Saharanpur on the U.P. side,” Sarvan announced. “Brother, you can give your demands, how many laborers you want and deposit five rupees per person, These five rupees will be utilized for their bus fare and apart from this we have decided that if the Chamars attack someone or entangle anybody in some legal case, the whole village must fight his case on his behalf and for that everyone mast deposit ten rupees per acre of their holdings. This money will be kept for fighting any case or for any situation that arises out of all this trouble. And suppose a person goes into the street and they start beating him on the pretext he has joked with their women or abased their women like that incident in Majari. Then we’ll use this money for fighting a court case against them.”

“Uh-huh,” said Sadhu, absorbed in trying to reach the soap to that difficult place in the small of his back. “Ah, yes, just hand me that bucket of warm water. Just push it a little closer, please. Ah, that’s it. O, yes, it is very good if you, have this arrangement. It’s safe for everyone. Oop, I can’t reach it yet. Yes, just a little closer; ah, that’s it. This water is not as hot as I wanted it.” He poured the warm water complacently over his head. “You take an active part, don’t worry.”

“For the time being,” Sarvan went on, exasperated and getting wet from his brother’s splashing, “we’ll take five rupees apiece. Now you give me twenty-five or thirty for the men you want.”

“Right now?” Sadhu Singh’s indignant bellow could be heard down the street.

“Yes,” said Sarvan, persistently, knowing his brother.

“Yes, but not right now, when I’m taking a bath.”

“Very well, you send it to my house in half an hour.”

“I’m not certain who we need. I will have to ask Charan.”

Sarvan left and Sadhu shrugged and went on leisurely splashing himself. He had worked up a good suds now and the san was very pleasant on his back. He had no intention of giving a single penny for such foolishness and within the hoar would be on the bus to Ludhiana to see if the university could arrange a reaper or cutting machine for him. While the old man had planned to spend the day resting on a charpoy, inviting a few friends for tea and listening to music on his transistor, he now raised his great bulk and hurriedly dried and dressed himself in a clean white shirt and pajamas. Then, pulling on his vest he harried across the fields toward the bus stop at the Bija Bridge with a vigor and briskness that would have startled anyone that knew him. For the old man knew there were times in life when it was necessary to stir oneself into action, and with all this foolishness in the village, this was one of them.

Under the banyan trees, Charan and his oldest son, Suka, Sindar and Gurmel and several others who were making ropes under its shades saw Sadhu Singh streak off. “Lanedar has really big steps when he’s going someplace,” laughed Charan, who guessed his father was going to the university to try and get a reaper.

“After taking bath he gets light and walks fast,” said Sindar, never at a loss for something to say.

“I heard they were not able to decide anything after the meeting this morning. All I saw was that the Harijans didn’t agree to a general rate and want to set payments field by field,” Charan went on. For a time they worked in silence with the only sound the coo of doves from the banyan tree.

“The Bandit’s a real man,” said a man in a red turban working on the other side of Sindar. “He won’t betray as and go to the Harijans.”

“O, he’ll get some Harijans,” said Charan. “He doesn’t give a damn about this boycott.” A man on a bicycle passed and Charan, who could never let anybody go by without some human contact, lunged out at him with laughter. “You always cut jokes when you pass this way.” “Not me,” called the man over his shoulder. “I never cut jokes.”

“My wheat is already too dry,” one of the men complained.

“You shouldn’t have burnt your sugar canes,” Charan said. “It affected your wheat.”

Peloo, who had been feeling lonesome as he often did alone in the cattle yard, came hobbling up and took over the other end of the rope Charan was making. “Wah-ee-wah!” Charan laughed. “Peloo has relieved Suka. Now don’t be at high speed, you raper of your mother. Don’t drag me.” Charan gave a roar of laughter then went into a coughing fit. “Tonight Peloo will go to his sister-in-law’s house. Sindar doesn’t know she’s secretly invited Peloo to spend the night.”

Peloo could only grin bat Sindar asked, “Is it true what the Sarpanch says about Peloo. That he’s really very strong and that he only comes once while his sister-in-law comes twice?” Peloo laughed in a strange mixture of gargles, gasps and sobs. Despite his affliction, he was an intelligent man and also a rich one; he had saved everything he had made for the past twenty years and Charan and his family sometimes secretly borrowed money from their stable hand.

“One hundred per cent correct,” said Charan.

One of Charan’s cronies wandered by, pausing to tell Charan, “I can die for liquor.”

“There’s still half a bottle from last nights,” said Charan, half-joking. “Where do you want to sit, here or in the barn? You’ve been drunk since morning, I bet. It you’d help me make ropes we’d have finished by now and we could drink easily. O, Peloo, you are just spoiling my son by taking his place. If we don’t start cutting in two or three days, the wheat will start shattering. The difference in its color is enormous now. One day that which was quite green the day before is now yellow.” Charan called to another man passing by. “You are also drunk during the day. Today I don*t see anyone who is sober.”

“It’s all this trouble,” said the man, who was drank. “These Harijans have a wrong bug in their heads which won’t let them settle anything. They think the Jats are really in a fix, which they are, and they exploit the situation. I’ll arrange a cutting machine and then you’ll see the doves fly over.”

“Still there are still sensible people among the Harijans,” Charan said seriously. “They feel they should settle. You talk about cutting the harvest. People won’t even get food to eat if it goes on like this. Mukhtar’s brother, a Harijan, told Surgit Singh, ‘If you’ll intervene we’ll come to terms, bat we won’t deal with that dahuli committee. ” Charan paused to shout, “Hat!” at a passing bullock cart to scare it in a roar of laughter. “I heard there are some new machines, combines, in Ludhiana. They cost a hundred rupees for an acre but they do everything, cutting, threshing, everything. If we use the old methods you have to spend fifty rupees per acre cutting and one hundred and twenty rupees or so threshing but a combine takes only a hundred for everything. I read about it in the Ludhiana Tribune. Slowly, slowly, Peloo, boy.”

“O, Shabash, Deaf Man,” called Sindar, who was sitting next to Charan. “Beat all of them. Go ahead, go ahead, get back. We’ll beat everybody.”

“Hey, Peloo,” Charan laughed. “Try to beat the Deaf Maui. Ah, here comes Scooter, Scooter, you can take over from Peloo and give him some rest?”

“O, Scooter.” called Sindar. “Do you want to go to the moon?”

“I’ll go, but I won’t come back. I’ll build my house there.”

“But on the way you’ll be torn to pieces by high winds.” Sindar, unlike Charan, never read newspapers. “We don’t need any laborers,” he went on. “Our big lion, the Deaf Man, is here. He’ll do as much as any three other Chamars.”

“They say they have eighty applications for that combine in Ludhiana,” Charan said.

“We should bury this boycott and forget the past,” said Gurmel.

Suka, Charan’s oldest son, brought tea. “All Charan’s sons are quiet like his wife,” laughed Sindar. “That’s because they’re not really his. “

“O, Suka, Suka,” Charan called to his son, who had gone to chase birds with a slingshot. “Probably he’s tired. But he still has to cut fodder now that Mukhtar’s gone. When you have to train a bullock, you have to take him along with the cart without any yoke and then you put a yoke on his neck and walk after them and finally you put the bullocks in the yoke of the cart. So that’s how we train Suka. He’s like a young bullock.” The others were silent. They knew Suka cursed his father behind his back and was insolent but that Charan closed his eyes to it.

“Peloo is yelling from the barn,” Sindar said, pointing back to the cattle yard. “He’s waving at Suka.”

“Suka didn’t fill the water tank like his father told him,” Scooter said, “Now catch Suka’s tail.”

Charan looked around but didn’t see his son. “He must have gone home. Peloo, go and tell him to finish his work.” For some moments he braided in silence, then said, “We’ll arrange for some men from outside. They’ll go straight to UP today to bring some men. If I ask for men, they say, it’s my duty to provide them food, shelter and work.”

“You come and pull my penis if you’re so found of pulling,” shouted Sindar to Gurmel, who was tugging at the rope.

“Two days after the boycott started, one Harijan came crying to me and said, ‘We are starving. We don’t have anything to eat. My son and I got eight rupees a day before and also cut grass and fodder for our buffalo. Charan sighed. “I told him, ‘You come to my field and take fodder for your buffalo and I’ll give you ghee to eat.’ But he said, ‘I can’t do it because there is a heavy fine.'”

“I know a man who sent his four sons to school like you do,” said Sindar, still thinking about Suka. “All four were fashionable students.

They wouldn’t work with their hands like your boys. The father waited in a queue at the railway station to get all-route tickets for them, so they could travel all around the world, anywhere just so he could get rid of them.”

Sukhdev, the rich farmer, passed on his motorcycle, calling out to Charan, “They’ll go to Saharanpur today. But we’ll settle ourselves because you, can’t rely on these dahulis.”

Two Harijans approached; one was smoking a hookah pipe.

“If you stop smoking,” Sindar said amiably to them, “the poor tobacco contractors will be starving. Now, my son, you stop smoking. You are on boycott.”

“O, the Jat has called you his son,” laughed one of the Harijans. “Are you his son?”

“It doesn’t make any difference if he is my son or I am his son,” the other told him.

“If you, are his son and he is your son, you must have good relations with the mothers, really enjoying,” Sindar joked and everybody laughed.

“O,” said Gurmel, “here comes that one-eyed person. That gossip monger wanted to make trouble the other day and I shut him up.”

“After he went away,” laughed Charan. Mohinder, dressed up for a change and wearing his glass eye, appeared fairly presentable. He shook hands with Charan and squatted under the banyan tree. “Now I’ll tell you the real story about Basant Singh,” he said. “So many people are making gossip that he abused Marata.”

“I know the real story,” said Charan, shutting the other up.

“‘Now we will go for men,” said One-Eye after some time. “Myself and two men more. We would have left by now but we haven’t been able to collect money from all the people. We will bring back a hundred men. We’re not hopeful of a settlement. Even if the Harijans are ready, we won’t agree. Some of their men will break discipline and come to terms, I’m hopeful as many as seventy per cent of the Harijans will desert their leaders and join the Jats when the harvest is ready. We will break their will.” He leaned forward toward Charan and lowered his high voice conspiratorially. “We don’t want that the Harijans and Jats should get loose from oar fingers. If we settle wages individually, we tell the Jats, you all will have to pay more. Then our leadership of the 13-member committee would have no meaning. We told the Harijans this morning that where there is a weak crop we must give three extra bales per acre. It may be any weak crop. But still they didn’t agree.”

“I was there,” said Charan. “I don’t remember anything about three bales.”

“O,” said One-Eye, quickly retreating. “But it happened so quickly. We didn’t have time to explain our position fully. He paused and giggled. “The Harijans can’t stand this for more than six months. It’s impossible. They’ll starve.”

“Maybe they will move away, get jobs in the city,” said Sindar.

“They won’t leave the village altogether. But we won’t bother if they go. We’ll bring more here and give them places to live.”

“How is everyone going to harvest?”

“Everyone will arrange individually outside and from their relations. And about seventy thousand U.P. wallahs are coming into Ludhiana District alone for the harvest. I heard it on the radio. We’ll bring one hundred, two hundred for you here. If we don’t get outside labor, our local labor will eat as up.”

Just then a police constable, in a red and khaki turban, rode up on a bicycle. He stopped between Charan and Sindar and asked, in stern voice, “Where is the 13-member committee?”

When One-Eye merely stared at the ground for some moments, Sindar pointed to him and volunteered, “Here’s one member, Mohinder Singh.”

“Ah, so you also are a member of the committee,” the policeman said, turning to One-Eye.

“Uh, yes. What do they want? Do they want as to gather?”

“Our inspector says he’s coming right now.”

“You’ll have to give advance warning. If you had told as last night we could have arranged a gathering. Even the Sarpanch is not in the village,” he lied. “If it’s suitable to us, you come tomorrow evening. If you would have informed us last evening, we could meet now. Unless you have all the members present, there’s no purpose in seeing the inspector.”

“My inspector told me he’ll be here at eleven or an hour from now and at that time collect as many as you can. Because he’s coming. Definitely. You just sign here against your name and don’t run off. The inspector told me last evening to come, but after some time he told me to go some other place. I suggested later but he said ‘No, I must come today only.'”

“Well, if he comes, we’ll try to gather as many as we can. Maybe four or five persons are in the village now.”

The constable nodded. “You go and collect your men and I’ll go to the Harijans and collect them. Even if we get only three or four, we can talk a little. I’ll take the village watchman with me.”

“The main boycott is that we won’t let them come into our fields.” One-Eye said as the policeman moved on. He turned to Charan, “The police seem to want that we reach an agreement.”

The police constable found the Sarpanch at home, washing his hair.

“I suggested to the Harijans not to break off any negotiation possibilities,” he told the policeman. “There is no point in trouble. It’s just a misunderstanding. If the boycott opens, everyone will go to work with some Jat with whom he’s had good relations. Who is coming?”

“Assistant Sub-Inspector Harchan Singh.”

“Good. Put the charpoys under the shade of the neem tree at the Gurdwara. It provides a good shade.”

“The boycott will have to end because anyone is mad to think otherwise,” Charan said after the policeman had gone. The Harijans earn their quota of grain for the fall year in these fifteen days. So they’re not so foolish as to lose their food for the full year.”

“Karam Singh of Kishangahr,” said Sindar. “I heard he gave the 30th bale before but another family has announced it will give the 25th. Because they want to take labor away from his fields. It is good if there are more enemies like that. It will help the Harijans.”

Gurmel called, “The Jats are making gossip because they boycotted us. O, somebody told me the Harijans would move to another village.”

“What village?” Charan asked.

“We won’t let you know. Otherwise the Jats would make mischief.”

Two hours later, when the men were still patiently braiding ropes and gossiping, the policeman returned, followed by One-Eye and Charan’s drinking companion, Nirmal, who was also on the 13-member committee.

“Now tell your officer,” One-Eye was saying, “We are leaving. He must come before tomorrow evening or our people will start reaping the wheat.”

“My officer didn’t turn up. I feel bored,” said the policeman, taking off his large turban. He was bald.

“Just take rest,” said Nirmal, “If he hadn’t sent you here, he would have sent you someplace else.” The policeman shook hands and bicycled off.

“Are you on your way to Saharanpur?” asked Charan.

“No,” said Nirmal. “We’ll go and sit in the railway station in Ludhiana and get people there. We heard there’s no point in going all the way to U.P. Two years ago, there was a government survey that seventy thousand men came from U.P. So we’ll go and sit there in the station, five or six of us. And as soon as we catch some laborers we’ll have one man bring them back here.”

“O, don’t ran to Ludhiana,” joked Gurmel slyly. “Come and talk to us.”

“Here comes the Sarpanch,” laughed Nirmal. He called out loudly, “Last night his wife was sick. He was riding her all night. Hey, O, Sarpanch Sahib, no matter how loud you cry now, the Harijans won’t elect you next time.”

“You’ve left all those poor people at the Gurdwara to be harassed by the police and you’re running away to Ludhiana,” the Sarpanch said.

“We should settle on the fifteenth part and let all the rich Jats suffer,” said Nirmal, sprawling his fat body on the ground. “Because now we know the Harijans won’t cut our wheat anyway. We’ll announce the 15th part and watch the biggies yell.” He yawned. “We know even at the 15th part nobody’s going to cut our poor crops.”

“The Sarpanch, Basant Singh and Surjit Singh are really behind this boycott,” whined One-Eye. “It’s not our fault.”

“We should create some real trouble so we can go to jail and other people in sympathy will cut our crop.” Nirmal yawned again and then chuckled. “Tonight we’ll enjoy a good girl in Ludhiana. O, Sarpanch Sahib, I heard your wife had to get dark glasses. His wife has to get special glasses because he’s always after her in the dark.”

After One-Eye and Nirmal had gone their way, Gurmel said, “If we accept anything from this 13-member committee, we’re fools. Who respects men like Nirmal and One-Eye?”

“Those U.P. wallahs know how to cut wheat but they’re not like Punjabis,” the Sarpanch said. “You have to have twice as many U.P. wallahs as Punjabis for the same field of wheat. Basant Singh just wanted to be goody nice in the eyes of the Jats but he’s the man who created the worst incident so far in the village. I told Mohinder and the others, ‘What do you gain by all this trouble? You are just making things unreasonable. We can calculate field by field if the Harijans want it. Why don’t you put your demands before the people and discuss them. Not just this fall stop, period.’ One-Eye replied, ‘O, not us alone but full stops from both sides.'”

“You know,” said Charan, who was thinking, “if one man breaks it, everything will be all right.”

“Yes, but soon.” The voice of the Sarpanch fell. “Don’t tell anyone else, but Nirmal and that one-eyed creature told me, ‘If anyone breaks the boycott, we will burn his fields.'”

Charan turned to see if anyone else had heard. “Next time we’ll have a tractor race also,” he shouted cheerfully to Sindar. “This time I challenged everybody but nobody was in the field.”

“Nobody can beat oar Charan on a tractor because he drinks too much.” Sindar said. “He won’t stay on the road but goes into the fields in all directions. Who else can do that?”

“You’re just bragging,” called Gurmel.

“If you think I’m bragging,” Charan laughed. “Come and test your arm.”

“He’ll make you piss, boy,” laughed Sindar.

“Bring anybody from the village who says he can bend my arm. I’ll give him a bottle.”

“Those who don’t want to harvest their wheat can test their strength with Charan,” said Sindar. “Then they can rest on their beds for a week.”

Sindar laughed. “My bullocks walk in the field like the chariot of a god. O, Deaf Man, why are you looking towards Mecca? Keep your eye on your partner at the end of the rope.”

“City life is good, Sindar,” called Gurmel.

“Take your children in big baskets if you go there. When they go hungry you can always thrown them on the railway tracks.”

“We’re afraid our children won’t be allowed in the school if the boycott keeps on. I’ll go to some big city after harvesting.”

Sindar laughed. “If you throw cow dung in a clean sack it will still give a bad smell. Wherever you go, they’ll know you’re a Chamar.”

“Never mind,” retorted Gurmel. “A law is going to be enforced where we’ll only work eight hours a day. Then we’ll apply to Indira Gandhi for a new road and we’ll buy bicycles and go to Khanna every day.”

Charan joined the joking. “Why don’t you, build an airstrip for Indira Gandhi’s airplane? You’d have to dismantle your houses, of course, since the Jats won’t allow you in their fields.”

“Look how the Chamars are sitting in their houses and enjoying while we make ropes in the heat,” Gurmel called. “This boycott has been a blessing in disguise. The Mazhbis are also on strike. Because Basant Singh abused a Mazhbi. This boycott is a loss to all.”

“If we had known beforehand,” said Sindar, “We would have mixed some poison in the cakes at the Gurdwara and poisoned all of you. I think today the Deaf Man has taken two rupees of opium. That’s why he is dancing so in the son.”

“No, I’m drunk because I can see your grains coming into my house after some days.

“If you Chamars want our cooperation, then you should give laying hens to all us bachelors.”

Gurmel laughed. “You’ll see Sindar’s face after harvesting. He will look as black as a railway guard. This time half the Jats will die of hard work. We’ll make them really skinny, out cutting their own wheat. They have too much fat on them. And now the Mazhbis are thinking of joining us.”

“C’mon, Deaf Man, move back. When the harvest comes, you’ll get your bottom torn by the stubble.”

“I’ll watch out for my bottom. I won’t cut too high. Last year we were cutting with the Jats and the Jats were far behind.”

“Move back, O, Deaf Man. Don t let your shadow fall on me. I’ll get lazy like you. Shabash, O Deaf Man, Shaba-a-a-ash.”

That evening as Charan went to his fields to bring fodder for his cattle, he passed Sher on the road and stopped to ask him if the Mazhbis were joining the boycott too.

“I don’t know,” Sher replied. “It’s our common problem, Sardarji. The issue is just nothing but both the Chamars and the Jats have taken a stand on an issue that is really no issue. And nobody wants to go back. Last year some of as used to cat on the 30th bale; about twenty or thirty men accepted this rate instead of grain.”

“You don’t see any problem and we don’t see any problem,” Charan said. “Then what’s the problem?”

“We have just taken stands. It’s a question of honor. Some of the men want to challenge the Jats’ authority, nothing else. If they have to go outside for work, sell their cattle, they’ll do it, that’s all.”

“Will you come with me on lavi, just take as much wheat as you can carry each day?”

“I don’t know. Come tomorrow night. Let me discuss it with the others.”

As they spoke, old Pritam approached on his way in from his fields on foot. Charan told him what Sher had said.

“I told the Mazhbis,” the old man said, “We have no grudge with you and we have no complaint against you, but if you stand with the Chamars we will have to treat you the same.'”

“If you ask us the truth, we are really in a fix,” said Sher. “Because we can’t pull on without working.”

“There’s no harm if you come on some other terms,” said Pritam.

“O, God, who tells you to come on the 30th bale,” said Charan. “You can come on other terms. We can agree to a settlement.”

“We are caught between the Jats and Chamars,” said Sher. “It’s a question of community prestige. After all, we have to live in this village and we know what’s happening here.”

Charan frowned. “Tomorrow the Chamars will tell you, ‘Don’t go to the Jats’ barns.’ You must suggest to the Chamars that they should compromise some way or another.”

Sher said, “Where the question of honor is concerned, when we work for daily wages, how is that a question of honor?”

Old Pritam sighed. “It is a dangerous day. There is every possibility of a storm. My body tells me because of these thin clouds and it is perfectly close.”

“How many days are left until you must reap?” Sher asked Charan.

“We have no such system of days. If you will come, come whenever you want.”

“Who would leave this lush grass by the roadside if the Chamars were allowed to cut fodder for their cattle?” muttered old Pritam. “O, a dust storm is coming. O, look, it is already there in the north.”

“Did you hear about Basant Singh abusing Marata?” Charan asked the old man.