A Study of the Human Impact of the New Seeds and Methods of Cultivation in Ghungrali-Rajputan, a Prosperous Village on the Punjab Plain in Northwest India

Part One: Charan

As a team of oxen are we driven

By the ploughman, our teacher

By the furrows made are thus writ

Our actions – on the earth, our paper.

The sweat of labor is as beads

Falling by the ploughman as seeds sown.

We reap according to our measure

Some for ourselves to keep, some to others give.

O Nanak, this is the way to truly live.

— From The Granth Sahib, the sacred scripture of tri Sikh religion

Contents

I CHARAN

Morning

Two Old Friends

The Mela

The Massacre

Charan

Honor

Il SEEDS OF CHANGE

Green Revolution

The Hunt

The Storm

III JATS AND HARIJANS

The Bullock Cart Race

The Boycott

IV THE HARVEST

Reaping

Threshing

Evening

Introductory note:

In an Article, “INTO THE 1970s” published in its December 27 1969 issue, the London Economist noted:

The 1970s have already been indelibly marked by the 1960s, but they will have their own successes, most probably in economic and technical advance, and their own lost opportunities, most likely the failures of liberal intelligences.

After a review of global security, the Economist considered at length five issues it felt were among the most important hopes and fears for the decade ahead. These included the likelihood of the rich countries attaining a 50 per cent increase in real income, the growth of giant international corporations, the race and generation gaps and the danger that political conditions and emotions might impede technological advance. The fifth issue, discussed in an article titled, “Green Revolution or Red?” was summarized:

In the poor two-thirds of the world there is likely to be a sharp increase both in the production of food and the number of unemployed farmers. In some of its overcrowded cities there may be mob-led revolution, as in France in 1789.

This is also the central theme of the following study, confined to a small group of farming villagers in the Punjab of Northwest India. The purpose of the study was not to seek answers but to further discover, define and describe the questions. It is part of a larger project exploring in a Mauritian fishing village the human impact of overpopulation and in villages in Java and the Nile Valley, the problems of mass unemployment and the flood of rural peoples to the cities, all aspects of the same overall theme.

This particular study, “Sketches of the Green Revolution,” which I have divided into four parts, is intended primarily to be read by economists, sociologists and agricultural technicians who are professionally involved in the agriculture revolution now taking place from Tunisia to the Philippines but who do not have the time to spend several months living in a village, as I did. Although I had no idea what I would find, my study mainly turns around a social confrontation and polarization, rooted in the economic change brought by the new seeds and methods of cultivation, between the Jats, or farmer-landowners of the village, and the Harijans or untouchables, who, whether they be Chamars, the traditional leatherworkers of the village, or Mazhbis, the sweepers, are being gradually forced into the role of either a rural proletariat or urban migrants.

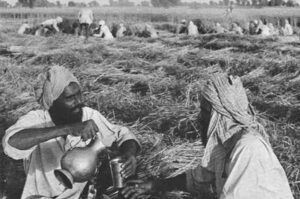

Initially, I attempted to follow the familiar approach used Oscar Lewis in his “Five Families.” in which he presented Mexican case studies in the culture of poverty through portraying a village family on a typical day, drawing upon detailed observation, interviews and recorded dialogue. Very early in my stay in Ghungrali I shifted from the family in a single day approach and instead focused on a single farm operation over a period of six weeks, from the first of April 1970, to May 5, the day I left Ghungrali. I did keep to the Lewis method of recording dialogue or “selective eavesdropping” as it has been called. As a journalist who has always relied on interviews, I was amazed how much more valid natural conversation is. The Punjabis, as the one autobiographical monologue presented may suggest, tend to “go dead” in interviews, just as they stiffened up at first when I started taking photographs. All the conversation in “Sketches” is drawn verbatim from some 120,000 words taken down, mostly in the fields, from February through the first week of May. I have taken the liberty of using some of the material gathered in interviews as thoughts by the villagers.

The present study is not complete. I plan to spend the month of October in Ghungrali during the sowing season, hopefully gathering in some of the loose ends. A final word on methodology: As in the Mauritian fishing village, I found it necessary to actually work with the farmers in Ghungrali, helping them cut fodder, harvest and so forth, in order to gain enough empathy and rapport. I knew no Punjabi and except for a few cultivated villagers who spoke English, I relied mostly on an interpreter, Krishanjit Singh, a distinguished Punjabi writer and translator who not only did an excellent job of interpreting but was blessed with a writer’s sensitivity and a Punjabi’s sense of humor. Two exceptions were the leading two characters, Charan and Mukhtar, with whom, working together every day, I was eventually able to converse at length in a mixture of fractured Hindi and broken English. A word about names. All Sikh men have the surname of “Singh,” which means “lion” and all Sikh women have the surname of “Kaur,” or “young prince.” Use of the last name connotes respect and formality; I have kept or dropped the Singh from the names of the villagers depending on the usage of those to whom I was closest, which seemed the most natural. Also, since I have used a smattering of Punjabi words without footnotes, a short glossary will follow part four.

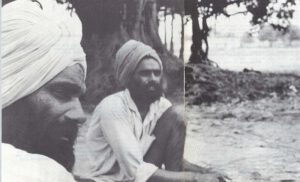

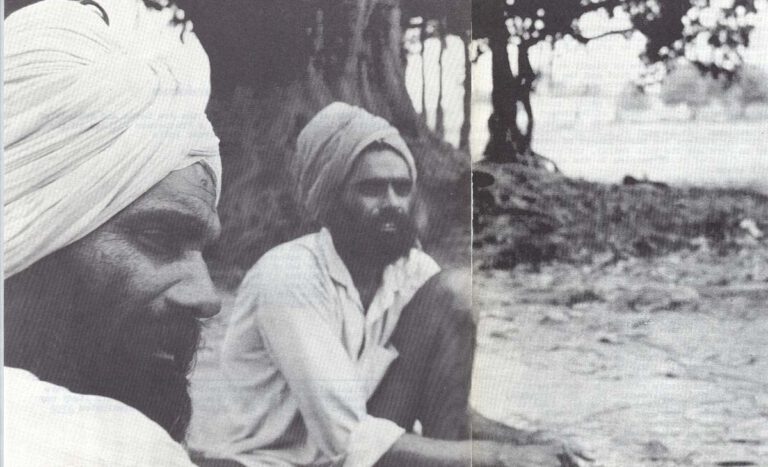

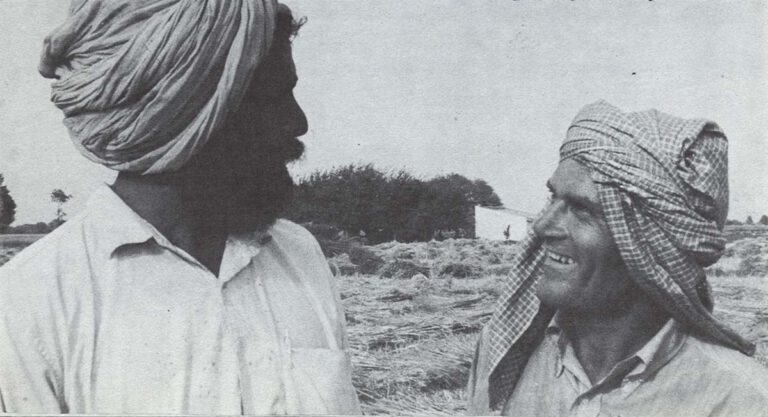

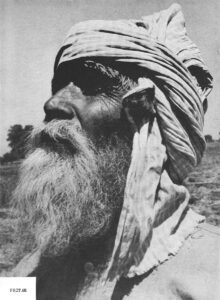

As will be self evident, I owe a great debt of gratitude to my interpreter, Krishanjit. I am also grateful to officials of the External Affairs Ministry and Food and Agriculture Ministry, Government oil India; Dr. M. S. Randhawa, Vice-Chancellor of Punjab Agricultural University and Dr. T. S. Sohal, professor of extension education for recommending Ghungrali and introducing me there; Wolf Ladijinsky of the World Bank and Chadbourne Gilpatric of the Rockefeller Foundation staffs in India. Finally, it is to Charan himself, who appears on the previous pages making rope and below with myself during threshing, that my deepest gratitude is owed. Not only for his hospitality but for encouraging me, as best an outsider could in a limited period of time, to make the study of Ghungrali as honestly true as I was able. It is at his request that I have used real names and made no attempt, to preserve anonymity. Photographs of Charan and the other principal characters, in the order of their appearance, follow on the next few pages.

Richard Critchfield

New Delhi-Singapore, May 27, 1970.

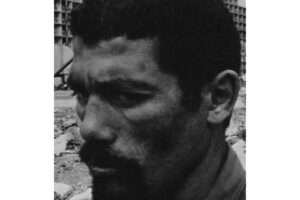

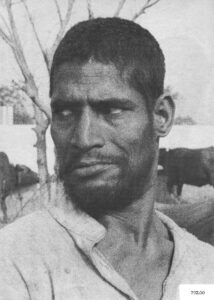

CHARAN

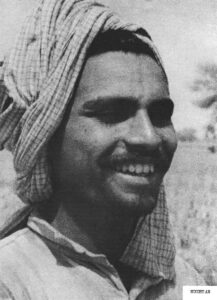

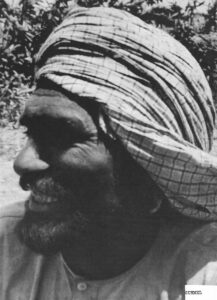

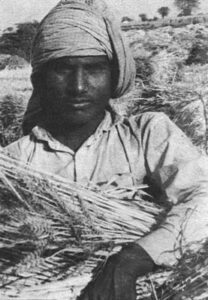

MUKHTAR

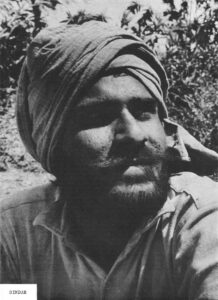

PRITAM

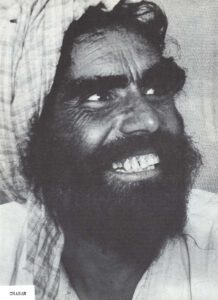

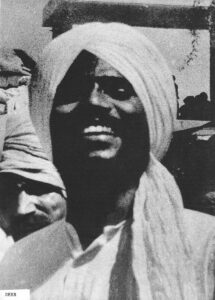

DHAKEL

GURMEL

SINDAR

SHER

PELOO

SURGIT

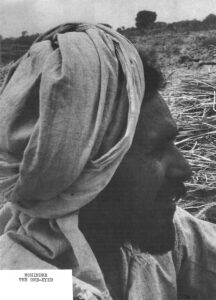

MOHINDER THE ONE-EYED

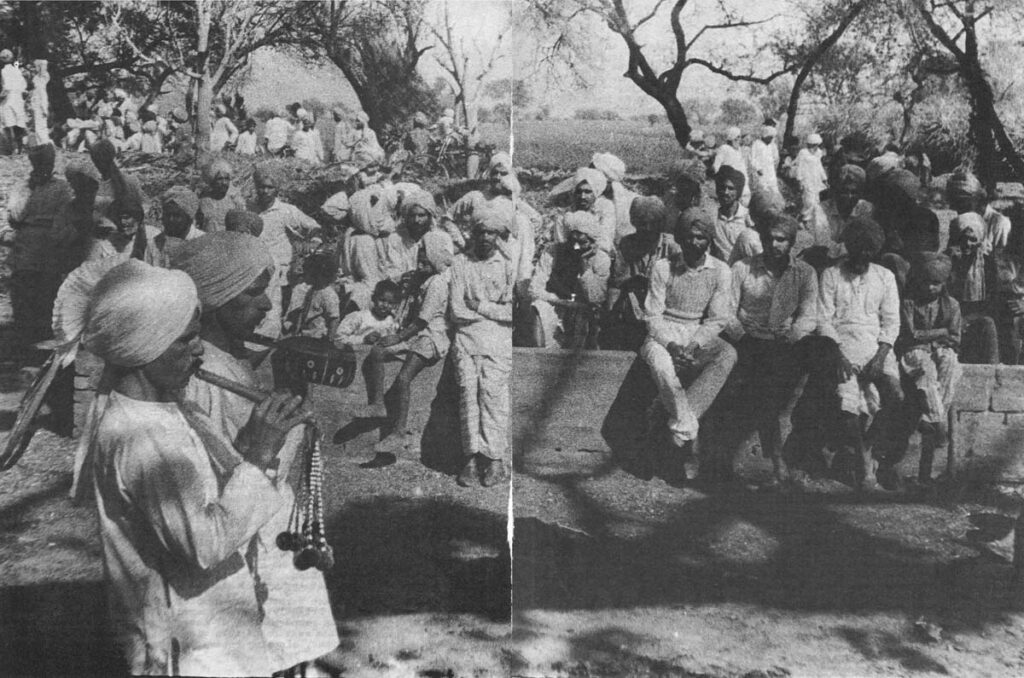

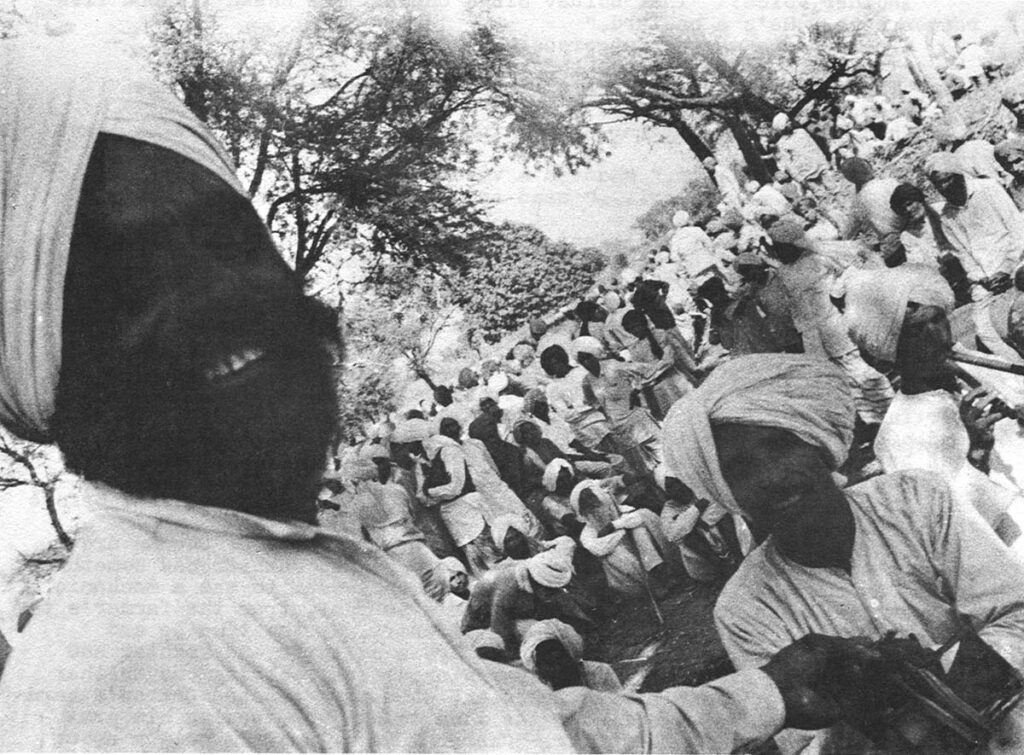

AND…THE MAZHBIS

DARSHAN

OLD CHANAN

BAWA

KAPUR

PART 1: CHARAN

Morning

Early one April morning a springless, bone-shaking bullock cart rumbles oat of Ghungrali-Rajputan, a prosperous Jat farming village just a few miles southwest of the Grand Trunk Road, that celebrated thoroughfare which stretches from the Khyber Pass across the Indus Valley to Delhi and on down to the Ganges and Calcutta; the villagers have only to go to the Road and see all the life of India flowing by and this is nowhere more true than where it crosses the vast, flat expanse of green and golden wheat lands that is known as the Punjab Plain.

The cart groans and utters a load creak at the slightest movement; a copper drinking vessel, hanging from a pole fixed to the cart’s side, chimes in, like a bell. By these sounds, apart from its pathetically worn wooden flanks, you might conclude as to the cart’s age and readiness to fall to pieces. In the cart sit two inhabitants of Ghungrali, Gurcharan Singh, a Jat farmer known as Charan to his friends, and his hired laborer, Mukhtar. As they move, Charan crouches on his haunches on the cart’s tongue, holding the reins and coaxing on the bullocks in that strange high-pitched falsetto language of praise and curses with which Punjabis address their cattle: “Tat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat. Ta-hah, ta-hah!” Charan calls. “O, your good fates. Go quickly or I’ll pull out your testicles. Tat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat, ta-ha-a-a-a-h!” The bullocks, grave and dignified, ignore him, keeping to the accustomed rats they have followed to the fields in the morning and back to the village at night these many years. This path is as much of their existence as the dusty, flat road in the countryside or the grassy, cool shade at Charan’s well where they munch on berries or sleep, rolling over on their sides, all day long.

Charan himself is in a sullen temper. That morning his father, the old patriarch, Sadhu Singh, showing nothing bat a towel-wrapped head and white beard above his down quilt, called to Charan from his bed, complaining that the buffaloes looked thin; the old man had grumpily fretted to his wife, “They don’t feed the cattle properly.” The Old Lady, busy churning milk, shouted to Charan’s second son, Kulwant; in the fierce-sounding screech in which she always spoke. “You! Go help Peloo feed the cattle!” The boy, sipping tea in a corner had replied in a defiant, bat low voice so his father would not hear, “I’m not used to it” and had stayed where he was.

Fed up at seeing the old man’s comfortable pot-bellied figure bundled warmly in its quilt, Charan for once lost his temper and told his father, “Then why don’t you get up and go feed them? You won’t lift your finger but you criticize as who do work all day. It’s very easy to find fault.”‘

The Old Lady, his mother, alarmed by this unusual outburst, had screeched to her husband, “He’s responsible for the wheat crop. Why should you talk aloud? Let him do whatever he likes. We’ll see when the wheat is harvested.”

“He acts as if I’m going to throw everything away,” Charan had stormed. “That anybody could take all I’ve built up all these years. I’m not doing that. And if you’re so worried about the cattle, go and attend to things yourself.” At that threat, Sadhu Singh, who had never done a day’s physical labor in all his sixty years, stayed silent and feigned sleep. Charan had strode out of the courtyard and down the village lane that led to the family’s cattle barn. There, hidden under a pile of freshly cut fodder, was a bottle of country liquor and Charan filled a glass to the brim and downed it in a single gulp. Peloo, the crippled, deaf and dumb stableman, who loved Charan as one of the few persons in the world who was kind to him, hobbled over to the pump to bring him water to wash the fiery staff down. Now, still angry over the exchange, Charan curses the bullocks, “Go quickly or I’ll rape your mother.”

Mukhtar, crouched on a pile of jute sacking-in the back of the cart, hears Charan and guesses why he is ill tempered. “Charan is a good man,” he thinks to himself, “but the old man and lady are always intervening. And they are mean, mean to the lowest.” Mukhtar is still half-dozing, even after a hot glass of tea and putting the bullocks into yoke. Charan has them well trained and only a command of “Tuk tuk, tuka. Get in place,” is enough; the bullocks understand and gravely step under the yoke themselves.

Mukhtar yawns. His wife awoke him at four o’clock so he could see a giant star with a long fiery tail like a comet’s which-had mysteriously appeared on the southern horizon three days before. It was said in the village to be an omen. The old men said such a star had only once before appeared and that was on the eve of the village massacre in 1947. Mukhtar himself was too young to remember. He was born just three days before thousands and thousands of Ghungrali’s former Moslem inhabitants had been slaughtered by the Sikhs and Banda soldiers.

“Charan, ji,” Mukhtar says, “I saw that star this morning.”

“I saw it too. I had a bad attack of asthma last night and had to wake up the doctor for an injection. They call it the star with a tail.”

“Some say it last appeared, in 1947.”

“Yes. They say that when such a star appears there will be a disaster in the village. But it has been there for some days now and nothing has happened.”

After that there is a silence. Mukhtar recalls how he lay in bed listening to the pre-dawn sounds. First, the chirp of the black sparrow who lived like a rat in holes in the fields. Then the women rising to churn milk, followed by the sound of the jupji or morning prayer from the Gurdwara’s loudspeaker.

There is One God.

He is the supreme truth.

He, The Creator….

Before time itself

There was truth.

When time began to run its course

He was the truth….

The prayer went on and on and Mukhtar lay in his cot, listening, to it. Finally, came the beginning of the final chorus, sang by the old people and children who always went to the Gurdwara in the morning:

Air, water and earth

Of these are we made….

At the end of the prayer, Mukhtar heard-footsteps in the lane outside his house; shrouded men wrapped in shawls and blankets, going to the fields to answer the call of nature. Mukhtar knew it was time to get up, hurry to Charan’s house for a cup of tea and then go and harness the bullocks.

Now as the cart passes the Gurdwara, Mukhtar looks up through the gate and sees the priest up on the hilltop raising prayer -flags over the holy place’s still shadowy white towers. Unconsciously, Mukhtar observes all the familiar houses on both sides of the lane, the usual huddle of brick and earth houses, some with high walls enclosing their cattle yards, vegetable gardens and verandas. Here is Bhoondi, the sweeper’s, whose four sons have already left for work in the fields; the house of Sarvan Singh, Charan’s uncle, with its green-painted baithak facing the lane; in its courtyard Dhakel, Sarvan’s son, and Sindar, a vagabond cousin who is the black sheep of the family, move around, putting their bullocks under the yoke; but the bullock cart Boon rumbles past them, leaving them and their sleeping occupants behind. And next, the square yellow schoolhouse, also built on a rise and almost hidden by the high brick wall around it, which also encloses the post office. Beyond the school stretches the spacious open ground around the village pond, now almost dried up. A faint pink tinge of heather has been brushed across the dusty earth. And beyond the pond is the village’s giant banyan tree. Some say it is more than a hundred and fifty years old.

Mukhtar wonders what tales the banyan tree could tell if it could speak. What elopements, swordfights, drunken quarrels, to say nothing of the massacre twenty-three years before. The banyan tree’s fantastic heavy branches extend thirty or forty feet in every direction; roots dangle from them, hanging straight downward like gray icicles. Under the banyan tree it is completely dark and the black shadows cast by its branches are just beginning to creep across the dusty earth and over the road.

The village comes to an end at the banyan tree and then begins the open country. Here the dirt road splits, one direction going toward the Grand Trunk Road to the east and the other, which the cart takes, toward the land allotments where Charan has his fields to the south. Beyond Charan’s new white-washed cattle yard and shed and the banyan tree and behind them farther down the road the small earthen hat where Mukhtar’s wife and baby still sleep, is only one more house, that of old Pritam Singh, a gentle, white-bearded giant of a man, who at seventy rivals only Charan as the strongest man in the village.

“Chota,” says Charan, who has called Mukhtar “Little One” ever since he was a child, “we will water, the south wheat field today from the canal. Take a hoe from the well shed and walks to the khal that brings the snow water from the Himalayas. If someone else is using, you will have to open ten or twelve bunds, if not, only one or two.”

“Han, ji.”

Meanwhile, the cart has moved out on the broad limitless plain, broken only here and there by clumps of trees around the wells and pump houses. One after another, almost identical in appearance, these small landholdings unfold before the eyes of the two men in the cart. The farms stretch on both sides of the dirt road as far as the horizon, flowing into a faint dusty white atmosphere. You can go on and on in the Punjab and never see where this horizon begins and where it ends. The scattered trees at the wells create the illusion of a distant jungle hang with mist but there is no jungle; the rich land is too valuable. Almost all of it is planted in wheat, mostly still green but a field here and there sowed early and already ripening into a golden hue. But what wheat! It is all short, stunted and dwarfed! A thick tangle of plump heads on short, stiff stems, growing in a carpet all the way to the horizon and beyond to cover the whole of the Punjab and Gangetic plains. To Muktar this wheat still seems a miracle after five years with its lush, almost artificial appearance and its many strange names: Khalyan Sona, PV 18, 227, RR21, Triple Dwarf. As the cart moves, Charan comments on each field, “This wheat is sick. It has a disease,” “Not enough fertilizer; he’s a poor farmer,” or “Now that’s a good crop. Yes, that’s right.”

The sun has already made its appearance, across the fields southeast of the village and slowly begins its day’s work. At first, a long way ahead of them on the dirt road, where the sky is divided from the earth near the misty white tree line, a broad yellow streak of light creeps across the fields; in a few moments that streak of light has come a little nearer the cart, crept to the right and acquired possession of the banyan tree’s upper branches behind them. Something warm touches the faces of Charan and Mukhtar, a streak of light rises steadily up in front, slips past the cart, rises to meet the other streak and suddenly all the wide plain casts aside the grayness of dawn, smiles and begins to sparkle with dew. Almost instantly the chill of the night is gone. The fields and fields of strange dwarfed wheat, pale green, dark green, here brushed with gold-at the grain head as the harvest nears, the green grass alongside the road, the wild roses in the ditches, the ripe silver oats, all a rusty brown-grey and half-dead from the April heat and dust the evening before, now bathed in. dew and caressed by the sun, revive, ready to flower again.

A flock of black crows, cawing and scolding, flies toward the village from their night’s roosting in the treetops of the fields and in the ancient oaks along the Grand Trunk Road, flapping their wings with eager cries. Sparrows twitter to each other in the grass; far away to the left somewhere a peacock wails, a strange sorrowful sound; the turtle doves begin to coo and a covey of partridges, startled by the cart, rise up, and with their soft “trrrr” fly away to the wheat fields and field mice, rats, mongeese and dusty green lizards rustle in the grass.

But hardly has the cart gone two furlongs more than the dew starts to evaporate, the air loses its freshness and the great Punjab plain begins to reassume its languishing April appearance. The grass droops and the sounds of life die away. The dying green of the sun-burnt wheat, the white distance with its tints as cool as water but really dry as dust and the perfect blue sky appear at this moment to threaten a day limitless and listless with heat.

“It will be hot today,” says Charan. The bullock cart creaks along and turns around a bend in the road. It is not far to Charan’s fields now. Mukhtar sees all the while the same thing: sky, wheat fields, the hazy dust of the distance in the bright sun. The sounds in the grass are gone, the peacock has flown away, there are no partridges to be seen. Tired of chirping, the sparrows hop toward shady places in the grass; they all resemble one another with their little brown heads and render the plain all the more uniform.

An Uncle’s Sparrow with a flowing movement of his wings soars in the air, then, shaking his wings, darts off like an arrow across the plain, and no one knows why he is flying off or what he seeks. In the distance, water is splashing from a tubewell, the outlet set high in the air so the farmer can see it from all his, fields; it resembles a small, artificial waterfall. The cart passes a very rich field of wheat. A black pot has been propped onto a stick in the midst of it, to scare off crows and keep away the evil eye of jealous neighbors. A chipmunk runs across the road; then once more Mukhtar settles down to reverie, watching the long expanses of wheat, the unvarying trees and pump houses. But now, thank God, a cart laden with dried cotton sticks is coming toward them. A man is lying on top of the load; he has been watering his fields all night. Sleepy and dozing in the sunlight, he just raises his head to look who is coming. Charan laughs, a surprisingly joyous, deep-throated laugh, and calls a greeting, the bullocks put out their heads toward the cotton sticks, the cart gives a piercing creak in salute.

“Sat Sri Akal, ji!” laughs Charan. “Ki hal chal hai? Are you hale and hearty?”

“Tik hai, maharaj, maaj hai,” comes a grinned reply. “Kush hun. I’m enjoying. I’m happy.”

“Pani lugya? Have you finished watering?”

“Yes, all night.” The man, whiskered and hard-faced with a curled, waxed moustache, is known in the village as the Bandit and has spent twenty years in prison. This has left him more worldly and easygoing than many of the villagers and he is popular, although he carries a flick knife in his pocket.

“Why is this sun so bright so early in the morning?” the Bandit asks, blinking his sleepy eyes.

“There is so much darkness inside you.” Charan laughs again, his eyes sparkling and his teeth flashing in the sun against his bushy black beard and prods the bullocks forward.

The Bandit smiles sleepily, moves his lips and lies down again. As they move on, Charan tells Mukhtar, “You know, he had no enmity with the man he killed. What happened was Gurbachan Singh was his friend. This Gurbachan had a dispute over land with another man. One day he and the Bandit got drunk and the third man was sleeping, in the Gurdwara. The Bandit hit the sleeping man with his sword and cut his hand off. The man awoke and raised his arm but blood was coming into his eyes and he couldn’t see properly. Gurbachan Singh then hit him with a sword seventy-two times. Gurbachan Singh was hanged. Now his land to the west of ours is held by his cousins. The Bandit went to jail for twenty years and last year got oat. They had been drinking that time for five days because Gurbachan had been blessed with his first son.” Charan shakes his head and praises the bullocks, “May you have many sons.”

And now, behind the fields of the stunted green wheat a single poplar tree is standing. Who put it there and why, no one knows. Mukhtar can hardly take his eye off its pale green color and cool shadow. Behind it is a bright yellow carpet of mustard and a field where the oats have been oat and gathered into sheaves. Elsewhere Mukhtar sees nothing but the green, green wheat. It will begin to ripen and tarn gold and then a dull, whitish brown in a week or two.

The cart passes two boys squatting side-by-side and rocking from foot to foot, swinging sickles and cutting fodder. Together they slash their sickles at the green barsim, grasping a handful at a time, advancing slowly, steadily, on and on until a dozen bales are cut, crouched low and nearly buried in the tall grass. The barsim swishes before them, as if tossed by a breeze. The sickles flash brightly and rhythmically; and both together make the same sound: grrch, grrch…. From the way the boys gather up the fodder after cutting, from their faces, by the glint on their sickles and their wet shirts, it is not difficult to see how oppressive the heat is going to be. A big Dalmatian with his tongue hanging out runs from the boys towards the cart, no doubt with the intention of teasing the bullocks. But he stops halfway and looks with indifference at Charan, and Mukhtar; it is too hot for such play.

One man, pausing in repairing an irrigation ditch, stands and holds his back with both hands, mops his brow as the cart passes and follows with his eyes its progress. He stands a long time looking at the cart without moving before he finally picks up his hoe and goes back to work again.

“Hat! Hat!” Charan coaxes the bullocks. Mukhtar now looks at the landscape with indifference. The prospect of the heat to come exhausts him, It seems they have been creaking and rattling a good long while although they have come less than a mile.

The look of geniality on Charan’s face too gradually wears off after they leave the Bandit, leaving only a sweat-beaded forehead and ferocious expression between the grimy yellow turban and the bushy black beard.

An old man, with a clean, faded blue cloth loosely wrapped around his head and holding in his hand a long staff – quite an Old Testament figure – rises from feeding sugar cane stalks into an iron crusher and, with a word to his laborers to keep the bullocks moving around in a circle to keep the crusher turning, and, folding his hands palms inward in the traditional Punjabi greeting, walks up to the cart. It is Pritam Singh, Charan’s neighbor and his father’s first cousin; he is known for his simple, hardworking life and humility. Above Pritam’s door in the village are inscribed the words, “O Nanak, I am drunk with the wine of God’s name day and night” and Charan has never heard him say a word in meanness or anger. A similar old Testament figure sits without moving on a bank watching Pritam and his workers crush cane; he looks unconcernedly at the passersby. It is Charan’s maternal uncle, Mamaji, whom Charan has already greeted early in the morning. Mamaji has come for a few days visit with Charan’s father and is an old friend of Pritam’s from the days both were neighbors in the family’s old village in Pakistan.

“Sat Sri Akal,” says Charan.

“Sat Sri Akal, ji,” loudly answers old Pritam.

“Sat Sri Akal,” repeats Mamaji standing now near the cane crusher.

“Are you hale and hearty, young man?” asks Charan.

The cart moves on and the old men remain behind, turning back to the cane crusher and their conversation. Charan’s fields are just through a grove of trees around Pritam’s well.

Mukhtar involuntarily looks into the white distance as the cart goes to the right, lurches into a rut and then creaks round a bend. Now Charan’s wheat is on both sides of the road. The cart turns off the road, goes a little distance over a bumpy canal ditch and then comes to a standstill in the shade of the oak trees. Mukhtar jumps off the cart and unhitches the bullocks, tying them in the shade. The two animals at once begin to gravely brose and munch on the grass. Three crows fly up to the oak branches above them and by their cawing express their agitation and annoyance at being driven from their grassy shade.

Old gray-bearded Chanan and Sher, the oldest son of Bhoondi, who cleans Charan’s barn, both of them cheerful Mazhbis, hired for a week to help with making gur, are already at the well. Chanan has lit a fire in an underground pit below a big iron pan and sits feeding cane husks into it. Sher waits for Charan to come and start the diesel engine, which will supply power to the iron-crashing machine, unlike old Pritam Singh’s old-fashioned method of using bollocks next door. Charan unlocks the white brick tool shed that gives his well its distinction – none of his neighbors has one yet – and utters an oath. Someone has emptied out a dram of residue from the crashed sugar, which he had planned to use for distilling some country liquor.

“It was your father, Sadhu Singh,” volunteers Sher to Charan. “He came last evening after you had gone and had as pour it oat. He said, ‘It does not behoove us. It is beneath our dignity.”

“It would have made thirty bottles.” Charan says with a shrug.

Mukhtar takes a hoe from the shed and starts across the fields. After a short distance, he stops and straddling an irrigation ditch in his bare feet, he bends over and carefully opens a small earthen band to let the flow of water through. Then he dredges the channel with care, deftly repairing the ditch as he moves to the canal like the natural farmer that he is. On his way back he stops at the well of Sarvan Singh, Charan’s uncle and closest neighbor, for a drink of water. The tubewell of Dhakel, Sarvan’s son who farms the land, is running and as he approaches it in the hot sunlight, Mukhtar hears a soft, very soothing murmur and feels something cool and refreshing on his face like another kind of air. From a deep hole in the earth runs a narrow stream of water through a steel pipe, installed there six years ago, as was Charan’s own tubewell. The stream of cold water, which runs into an irrigation ditch and alongside a field of oats, is as clear and mossy as a woodland brook; from the pipe the water playfully splashes to the ground, glistens in the sun and babbling gently, flows smoothly toward the fields. At the well itself, a little pool has been formed around which grows some green thick luxuriant grass.

Near the well Dhakel, his sharecropper Gurmel and Sindar, another of Charan’s cousins, are planting vegetable seeds.

“This small hoe is better than a big spade,” Dhakel is saying, “We must go to Bhambadi today and get more seeds.”

“We shall show them how our bollocks ran like railway engines,” says Sindar, who always has a comment for everything.

“There is just a little left,” says Gurmel. “I’ll finish it in just a few minutes. I’ve completed six rows.” The sharecropper starts singing as he works:

Oi, a scorpion bit me when I was picking

berries from a thorny bush.….

O, my fancy, it you come to see me in the

guise of a cousin and bring your bride, I shall

give her earrings but to you only a big round plate

full of sweet juicy milk….

“There are many people in the village,” observes Sindar in his rather high nasal voice, “those who won’t sway their limbs at the time of sowing vegetables and they’ll be buying by and by, throwing away a bucketful of wheat grains just for nothing. Look how lethargic they are.”

“Yes, they are Used to it.” says Mukhtar, joining the conversation. “In fact, they are really eating the wheat instead of vegetables.” Sindar laughs and the men talk on while they work in the rambling style of men conversing at labor, drifting from one topic to another and back again.

“These are really big seedlings. They are hard to grow. Aren’t you going to plant watermelons?”

“We should. Let’s do some in the next few days.”

“Yes, just sow some watermelon seeds and forget about it. You’ll have enough for your family.”

“You can bring some lady fingers and eat chilies with them.”

Sindar chuckled. “If you eat green chilies you won’t have enough stamina to satisfy a woman,” Sindar calls to Gurmel, who is slightly hard of hearing in one ear, “O, Deaf Man, this land dispute I have at Isaru. You see I want to take possession. They’re my uncles who farm it now. Four acres that are legally in my name. They’re real bastards.”

“Most of the people are, there in Isaru,” agrees Mukhtar, “They are really furious. They drink every day and abuse people who pass through the village. On which side is your land?”

“It’s just this side, by the brick kiln.”

“Yes, I know where that is. If you go to the kiln, it will be toward Gharala on the left side. If you go to village Gharala near the well of the sarpanch.”

“O, I know. We have not been that side for a long time. Not since the mela last August.”

Gurmel finishes planting a row and straightens up, both his hands holding his back. “O, have you heard?” he asks. “There went, a Jat to Majari to seduce this Harijan girl. He was chasing this girl. Before that he had been in that village and had abused the Harijans. He was just riding that girl when the Harijans came and caught him. They started cutting him with spears and swords. He’s in the hospital now. He’ll die, they say. Ruthlessly, they started killing him. He was forcibly raping this Harijan girl. He had some enmity with her brothers. But she was not their real sister. Perhaps a cousin.”

Gurmel watches Sindar for a response but Sindar instead tells him to keep more distance between the seeds. Gurmel changes the subject. “Shall we ask four or five people with rifles if you really want to take possession of your land?”

“I have enough men with rifles.”

“The men I’m talking about have a passport for shooting people. They’ll set them right.”

“Will you come with me, O Deaf Man?”

“Will you give a pension for my children?”

“You’d be useless anyway. Sitting by the well, drinking wine and getting drunk.”

Sindar wants to water the seeds but Dhakel, Gurmel and Mukhtar disagree. Then Gurmel says he will bring two pitchers of water, “That will be enough for them.”

“Yes. We don’t need much water,” agrees Sindar. “Just bring a bucket and a pitcher fall. That will be enough.”

“The best vegetable is small pumpkins.”

“If we throw the hay somewhere else we could plant watermelons where that haystack is.”

Gurmel brings some water but Dhakel is impatient to start some other work. He calls, “Hurry up, hurry up, are you killing flies?”

“I’m doing my best. Now I’ll make distances between them because these plants will grow all sizes.”

“I’ve heard Amar is the same,” Sindar says to Dhakel, referring to a cousin whose mind went blank after drinking country liquor all one day. “He doesn’t speak and talk. Always keeps lying in bed.”

“Have they brought him home?” Dhakel asks.

“Yes, he’s lying there deaf and dumb, looking always in the air. He has become useless. After completing this job we should start cutting sugar cane. There is enough moisture in the fields. We don’t need to water for another eight or ten days.”

Dhakel sighs. “Our labors are yet to come, cutting the sugar cane.” “Now the wheat is all right. We don’t have to bother about it. We should look to the sugar cane. It will be too late otherwise.”

Dhakel notices the seedlings are withering in the sun. “They’re going to die.”

“They’ll die once and then they’ll come up again,” Sindar reassures him.

Gurmel returns and Dhakel tells him, “One pitcher will be enough for one row.”

“Once they start growing up then you, should spray some cow dung on them. Then you’ll see those plants shoot up like pistols,” advises Sindar.

Gurmel finishes watering and turns to the sky. “Now you food giver,” he tells God, “you stay sunny and clear.”

“Now the bastard will pour more rains when we don’t need them.” says Sindar. “There shouldn’t be rains in March. We don’t need at all.”

Gurmel laughs. “This month farmers are afraid of Old Grandfather up there. They say, ‘Grandfather, just be nice to us.'”

Dhakel gestures toward the hoes. “Now, pick up these weapons. Let’s move.”

As they walk to the well, Sindar observes, “We must pick that banana tree because it is squeezing the roots of the mango beside it. O, Dhakel, there is a lot of that new foxtail weed in the wheat.”

“I know. It never happened before.”

At the well, Sarvan Singh is waiting. He has brought tea. Like Dhakel he is a man of strikingly handsome features, but a humble and mild disposition. Some of the villagers say it is because he has been eating opium for almost forty years.

He tells them he has passed a field of wheat, which has fallen in the wind. “Yes.” Sindar replies, “Nobody can help it.

“Now start cutting the sugar cane,” Sarvan goes on. “It also has been affected by the winds these days. And look how those oats have been twisted around and bent over. This was Gurmel’s share and he wanted to make it strong and put too much fertilizer on it.” Gurmel answers, “Mine has already had one more cutting than yours.”

“They say at the university put five quintals of fertilizer per acre,” says Sindar. “But we should give two and a half. Our land is very rich. Otherwise the crop will go off its feet and fall over. Where the land is poor, fertilizer works the best.”

“O, one thing happened today.” Gurmel tells old Sarvan. When I got up a snake fell from the roof. Maybe it was trying to catch sparrows.”

“Once when a snake came here.” says Sindar, “he was hypnotized by the sound of the engine and stood erect. Sometimes watering at nights we really come across so many snakes but they don’t harm as. Once I was sleeping on a charpoy under that tree. When I got up I saw a snake slipping under my bed. I thought, ‘O, my sister’s husband. I would have been eaten by that. But I’m saved.'”

“Gurmel, how long was that snake that fell from your ceiling?” asks Mukhtar.

“An arm’s length. Black.”

“When we were picking up that hay,” Sindar says, “there was a snake about three arms long.”

“There lives a snake there, near that kikar tree,” says Dhakel.

“Let’s kill him.” But as usual Sindar keeps sitting. The men sip their tea and Sarvan offers a glass to Mukhtar.

“Are you going to the Jarg Mela?” Mukhtar asks. “Charan is taking the tractor.”

“No,” answers Dhakel. “We have to cut our sugar cane. Otherwise we must go.”

“I have not seen many melas except once in Khanna,” Sindar says. “In fact, there is no good mela except Hola Mahalla in Anandpur Sahib. The rest of the melas are the cause of fights. People get drunk and start abasing each other. If some fool makes the mistake of abasing someone like me he would find his head apart from his body the next moment. What are these melas? What does a mela mean if you don’t beat someone to death? Some owls never stop abusing some unknown man. And they get a good beating. A few men tolerate abuses. But those like me can’t stand this sort of nonsense. My way is first never go to any mela. If at all you do go carry a kirpan with you. But I like bullock cart races better. Whenever I hear of one arranged I am the first person to reach there. But these dirty melas are generally for these Mazhbis and Chamars.”

“Yes, that last dose of fertilizer made this mess,” sighs old Sarvan, who has not been listening to his nephew’s aimless talking. “You must spray when you, sow wheat. But afterward in applying extra doses you must be very careful. Otherwise this new wheat goes app immediately up, and lodges in the first bad wind.”

“Yes,” agrees Sindar. “We made a mistake. Next time we’ll put on only desi manure after the first time. If we follow these university wallahs, due to overdoses of fertilizer, there won’t be any wheat at all. We don’t follow their rules.”

Two old men wearing spectacles and carrying cloth sacks approach.

Dhakel says, “They’re Harijans. They want to weed our wheat fields to get fodder for their buffaloes.”

Sindar says, “Let them. But they should be careful. They should not break the wheat stalks.”

The two old men greet Sarvan and there is an exchange of “Sat Sri Akal’s.” One of them tells Sarvan, “Your garlic will take another month or two to ripen.”

“Yes.”

As the Harijans move on, Dhakel and Sindar go with Sarvan to see how much wheat has lodged and Mukhtar follows Gurmel who goes to cat oats for fodder. When they are out of earshot of the three Jats, Gurmel asks, “Well, how does it go with Charan? Two sharecroppers have already run away from him this year. Of course, you, Mukhtar, you are a daily laborer and can quit when you like. You are not chained to these Jats on a year’s contract like I am.”

“Charan himself is very nice,” Mukhtar says, “but it’s the mother and father who are really mean. I needed two rupees this morning and they wouldn’t give although they had it and they owe me forty. I told Charan and he got it for me.”

“They’re so mean,” Gurmel nods, cutting the oats as they crouch and talk, half-buried in the oat field. “Everyone in the village knows it.”

“The mother is the meanest. She’s mean to the lowest. There was a person, a Mazhbi, who wanted to buy an old fodder-cutting machine from Charan. Charan told him one day, ‘Are you looking for a fodder cutter? Look, I have one there, lying there rusting.’ The man saw it and decided to bay. They reached a bargain. The man would pay forty rupees. When this person came back to take the machine, Charan had gone away and the mother and father were in the barnyard and accused him of theft. And the Mazhbi was very angry and insulted. The old lady said, ‘You have come to loot our barn like a bandit.’ They should have asked their son before insulting someone like that.

“Yes,” Gurmel agrees. “If it had been a Jat they might-have had real trouble. I am fed up with working for these Jats. These days we Harijans are more inclined to take odd jobs instead of being sharecroppers for these Jats. In my case, I have a goat I bought for one-hundred-fifty rupees. If Guru is in my favor, this goat will give me two lambs worth a hundred rupees each. I have a cow, a buffalo, also which will give me calves in two or three months. Last year I bought this buffalo for a thousand rupees and now I sell milk worth ten rupees every day. The government is a big addition to my assets and now they have opened a new dairy and milk collecting station at the Bija bridge. Why should I be a sharecropper and get my skin eaten up by these Jats when I can earn more than I am earning here? I shall be having milk all over my house soon. And you know from seeing my house that it is as good as Charan’s.”

“Before you came, Mukhtar, they were talking about my meals, that I eat too much. What do they give me? Just two chapattis a day. This is part of the contract. They must give me hazri. Next year of my seven brothers only one will be a sharecropper. But I won’t be if Guru grants me healthy limbs.”

“The Jats may be strong, but they can’t work as hard as we Harijans,” says Mukhtar.

“Aye. Take Basant Singh. He used to treat Harijans like animals. Give them the worst food to eat and try to take the most work out of their skins. Harijans stopped going to him, even as daily wageworkers. Now he has taken a right line. He has had a lesson that if he treats Harijans like animals they will also start treating him like an untouchable. It was a sort of undeclared boycott.”

“When did Sindar come back? He has not been around here for some weeks.”

“He?” Gurmel cursed scornfully. “Now he is telling people he is Dhakel’s brother, that vagabond. He is only a cousin,” Gurmel looks over the oats and sees Dhakel and Sindar have moved far away across the fields. His voice becomes confidential. “Now I shall tell you the real story. The truth is that Sindar is a bastard. His mother was married to a man in Isaru village. She left him and went to another person near Kharar. He was an old man and used to do bad works. He was smuggling opium. Sindar was born in Isaru and one brother and sister from that bad man. Both fathers are now dead. His mother lives near Kharar and has land. It is about sixteen acres oat of which she has put six in Sindar’s name bat she will never let the bastard touch her property now. Legally, it’s his right.

“In this village of Isaru he also has four acres of land, about which he was talking this morning. His uncles and cousins are plowing there. So now he takes opium. It is not known to everybody. Only I know. Now he’s here for some days. He’ll run away when the harvesting starts. He knows they won’t give him food unless he works on their land.”

“What was that story you were telling about the Harijan girl being raped in Majari?”

“Ah, that. There is a man in village Kishangahr; he has some property in Majari. About six acres of land. In his mother’s name. And the Harijans involved, they are seven brothers, Chamars like us. One of them is a murderer. He was in jail for many years. But now he is out. His main job was to murder for money. He is the girl’s brother. He charges four thousand rupees for a killing. One day he was not at home. And this Jat from Kishangahr came. He has a grudge against Harijans because they were once tenants of his land and they tried to claim possession. This Jat went to the house of the seven brothers. It was Lohri, the 13th of January and the Harijans were burning fires to celebrate. So this Jat came and abased every one of the family members and went home safely. Four days ago he went back again and crashed his tractor against the door of the Harijans house. He was real drunk. He was immediately caught by all seven brothers and beaten with lathis, spears and gandasas. Now he’s in the hospital. I said he was raping the sister. That part is not true. The Harijans of Majari made up that story to excuse their beating of him. So the Jats will not know it was a land issue and unite against them. So we are spreading the story around all the villages. The dispute was over land only. But the Jats must not know this. They mast think the seven brothers were avenging their sister’s honor. He may die in the hospital. His head and arms are cut. He had a grudge against them because they used to plough his land and he repossessed with difficulty. They had been working the land more than three years and under the new law had legal claim to it. But tell everyone the story about the sister, Brother.”

Gurmel’s voice drops to a whisper as he sees Charan approaching across the oat field. Charan stops at a haystack and calls Mukhtar to come and help him. Charan tears off the top crust of the hay because it is encrusted with dirt. He pitches the hay onto jute sacking the two Harijans spread out on the ground and Gurmel and Mukhtar each takes a bundle on his head back to Charan’s well.

“Dhakel Singh should not have started cutting those oats until the plant is fall and gets some grain on it,” Gurmel observes.

“Yes, with grains it is good for milk cattle,” Mukhtar agrees. “Why are they in such haste?”

“They always know better themselves, these Jats.”

Charan, overhearing, comes up impatiently behind them carrying his fork, “Come, come, give me way to pass.” Mukhtar moves aside, balancing the huge bale on his head. Gurmel and He leave the bales on Charan’s bullock cart and stop at the pump for a drink of water. Gurmel looks across at Pritam Singh’s well where Pritam and his workers are making gur.

Mukhtar: “Pritam Singh used to draw four and a half maunds of water from a well eighty foot deep. (one maund=82 pounds) Everyone knew that Pritam was very strong. But once some men in the village played a trick on him. While he was coming from the fields, they tied a big rock weighing about thirty kilos to the bottom of a water bucket and lowered it into the well. When Pritam came by they asked him to see if he could help them and draw the bucket up. He drew about five and a half maunds of water and rock from a soft deep well with ease and asked them, ‘Brothers, is there any more help I can give you?’ He never knew it was a joke and since then nobody ever dared try another trick on him. Instead they respect him and he goes his way and does his work and doesn’t bother anyone. He is very modest and will never say he is the strongest man in the village. Maybe, perhaps, after Charan.”

Charan, hearing his name, calls to the two laborers; “There is a new record in our village. Two sons with one father and two different mothers. They came to the field yesterday. One with bullocks and plough, and the other with seeds. One ploughed all day and the other sprinkled seeds in the furrows. They sowed half an acre of land and came back to the village. Then they brought back a plank to smooth the earth. But they never spoke a word to each other all day.”

“I know them,” Mukhtar calls to him. “It’s their manner. Some people are like this.”

Gurmel returns to his oats and Mukhtar takes up the hoe and turns toward the irrigation canal again. He looks at the landscape, seeing exactly the same as that which he had seen earlier in the morning in the bullock cart and on his walk through the fields: the ripening bat still green wheat, the trees and pump houses, the sky, the white dusty distance. He looks back at the village and can see only three or four houses in the mist. There is no life to be seen near the walls or roofs from this distance, nor water, nor shade, just as if Ghungrali had been overcome by the burning rays and dried away. Mukhtar turns to his work; the wheat must have water.

Two Old Friends

“Putchkar, putchkar. O, may you die!” the boy aimlessly called to the bullocks, swatting their flanks with his stick as he followed them round and round the cane crusher. “Ham bol de. You remember God.”

Then, for a time, no sound of voices; one heard the bullocks, one white and one tawny, munching and snaffling; somewhere quite far away came the plaintive cry of a peacock, the mated song of the cuckoo and the persistent irritable cawing of crows and the high, twitter of the sparrows. But all these sounds and the boy’s occasional cry to the bullocks did not break the silence, they did not stir the stagnant air, rather they lulled it to sleep.

Gurdev, the sharecropper, oppressed by the heat and the silence, paused in feeding husks to the fire below the gur pan and called to the boy, “You’ll have rice with milk and sugar today.”

“O, no, I’m not that lucky.”

“If you put black peppers in it, it’s good.”

But the boy has started singing, tapping the bullocks’ flanks to the beat.

Come and dance, Nasid Kaur, come and dance.

“Hey, Scooter!” Gurdev called to a Mazhibi cutting fodder in the next field. “We had a bet yesterday for two bottles of liquor. Our sardar’s son and one Chand Singh. They told as they had seven bales of oats to cat on the machine. They gave as a ten paisa coin to fetch some hot cakes from village Chazipur. ‘If we finish cutting these seven bales and load them onto the bullock cart before you return,’ they said, ‘you will have to give as two bottles. But if you return before we finish cutting, we’ll be giving you.’ When we returned they hadn’t even cut half the oats on the machine yet. What to talk about loading them on the cart!”

“We will get the bottles out of them,” the boy said, “Now they’re making excuses. When it went into the machine, they say, sometimes the oats got stuck. Haphal gaya.”

Gurdev laughed. “When they saw me coming back there was muck panic and confusion among those two.”

Surjit, a tall, stout Jat and the youngest son of old Pritam Singh, listened to Gurdev as he approached carrying a load of sugarcane to the crusher. “It was the machine’s fault,” he called to Scooter. “Now we have decided to give them one bottle instead of two.”

The boy was singing again.

Come and dance, Nasid Kaur, come and dance.

Gurdev grinned. “The decision was one bottle which they promised to give as today. So it’s decided to give as one bottle, is it?”

“We’ll give you in the evening.”

“See our bravery,” Gurdev said laughing. “We agree to one bottle instead of two. We are Harijan sharecroppers and they are Jat landlords.”

“They’re afraid they may lose that one also.” Surjit said. “They think that we, husbands of their sisters, won’t give them that bottle also. Then there will be a quarrel between them, because Boy was one field behind Gurdev.”

“No, we came together. He’s lying,” called the boy from behind the bullocks.

“Why don’t you pick a quarrel with the Boy, Gurdev?” Surjit asked. “Don’t talk to me. Iron it out between yourselves.”

“Look I’m an old man and he’s a young boy,” grinned Gurdev.

“You were running like a jackal last night.”

The boy sang:

O, sealed bottle of Nabha town

If we see you we get drunk at the sight of you

O, sealed bottle of Nabha

We’ll break your cork at four in the afternoon.

“Maybe you had bicycles hidden in the fields and went by cycle,” said Surjit.

“No, no, we went jumping through the fields,” Gurdev answered him. “Then we bought ten paisa cakes from the shopkeeper. If we couldn’t have got the cakes, we would have brought gold sugar candy. We ran straight to that white house. People were calling on the way, ‘Why are you running?’ I shouted back, ‘Brothers, we have a bet.'”

The boy said, “To some we called, ‘There is a hare running before us and we are going to kill him.”

“You were covered all over with sweat from cutting the oats and we were wet all over from running.”

“We had a lot of fun,” said the boy.

“Come in the evening,” said Surjit. “We’ll give you. Was it a mile from here?”

“It was about twenty-five acres.” Just then a Shikara hawk flew overhead, stopped, changed direction in mid-air and flew off in pursuit of sparrows.

Come and dance, Nasib Kaur, come and dance.

The boy stopped singing, “Uncle, today we’ll go to the circus. I saw a searchlight from Khanna last night. O, Scooter is coming to join as.”

Scooter, a short-statured but stout Mazhbi with a black beard evenly fringed white beneath the chin, sat down on the canal bank near Gurdev at the fire and lit a cigarette, his sickle dangling over one shoulder.

“Are you hale and hearty, Scooter?” laughed Gurdev. “Sit down. So what do you think of our bet, yesterday?”

“Be careful.” warned Surjit, who was stirring the boiling gar. “You’ll lose the second bottle also.”

“Something must have stuck inside the machine,” grinned Scooter. “Otherwise you couldn’t have beaten these Jats.”

“We brought seven bales and we sharpened the cutter for them and we spread jute sacks on the ground.” said Gurdev. “They started running the motor and we started running. They called ‘Wahgru!’ and started pushing oats into the cutter and we shouted ‘Wahgru!’ and started running to Ghazipur.”

“Chand was just blind.” laughed the boy. “Re was running every which way, like a blind man.”

Surjit growled, “This black boy was two acres behind Gurdev when they got back and ultimately we decided to pay just one bottle.”

“When we came to yoke the bullocks we couldn’t walk.” said the boy, “Our legs were stuck. Chand started abasing as, ‘For what do you want the two bottles?'”

“We tried to find the person who sells liquor but we couldn’t find him,” said Surjit. “Now if they keep on talking about it, they’ll lose the second bottle.”

“Yes, they have no right to make such a fuss,” laughed Scooter. “Let them lose the second bottle.”

Gurdev said, “Today we’ll ran to Karnail Singh’s house in Ghazipur and break a twig and bring it.”

Scooter laughed, “If you like we’ll bring his wife also.”

Surjit said, “Get ready, Scooter. Do you think you can run so far?”

Scooter sighed. “We’ll run the day after tomorrow. I’m not, greedy for drink like Gurdev.”

“Here, have some sugar juice,” offered Surjit.

Scooter went to the crasher and dipped his finger into the bucket of raas or sugar juice. “O, I can’t relish this today.”‘

“It’s because you’re weak.”

“Now you have grown old,” said the boy. “Your hair is turning gray. I used to drink one kilo myself.”

“I’ll drink five kilos if you like,” said Scooter.

Gurdev laughed. “If you drink five kilos you will be sitting all day in the field with your shorts down.”

“The searchlight last night came from a circus,” said the boy.

“Elephants, camels, ladies,” sighed Gurdev. “And me with no money and no bottle.”

Just then Pritam Singh approached, through the fields, carrying a brass container of hot tea. The men paused in their work and gathered in a semi-circle, squatting as Pritam poured tea into their upraised glasses.

The old man, who still at seventy worked in the fields all day, had a gentle, saintly expression of face. Pritam would never see the Sistine Chapel, indeed, he had never heard of Michelangelo or was even aware of his own physical beauty; he would have been humbled and amazed to learn that the greatest artist of the Western world had once fashioned his image of God in a face and physique very close to Pritam’s own.

After tea, the men return to work and Pritam goes to the crusher and sitting on the ground, feeds the cane into the rotating iron cylinders. The bullocks are attached to the crusher by a log and each time they make a round Pritam must duck his head because of his great size. But he is used to it and seems to do it almost unconsciously.

Gurdev called to the boy, “You work seriously now, Boy, like a man.”

“If you don’t think me a man.” the boy called back, “what are you, a pair of trousers?” The boy turned to Pritam. “He called me a chicken earlier so there’s no harm if I call him a pair of trousers. O, bullocks move forward. May you live long. The crusher makes noises.

Pritam answered, “Yes, a little.”

“Don’t worry. We’ll fix it tonight if we can.”

“What about your bottles?” Pritam asked.

“We’ll have tonight.”

“I heard you had last night.”

“We didn’t find the man who sells the bottles.”

“I know everything,” Pritam teased the boy. “You had last night. Don’t try to fool me.”

“Have you finished?” the boy asked Pritam, meaning had the sugar cane all been cut.

“Why should we be finished,” Pritam smiled. “The finished are those who don’t come back to this earth. We are the living.”

“Some will go on working until they die,” said Surjit. “Those who can afford it they stop working at sixty; those who can’t go on working until they drop dead in the fields. But a person who sits on a charpoy all day must sell his lands or he can’t eat. While a man who works remains healthy.”

“It’s true,” agrees the old man. “Work can keep your health. An idle man gets lead in his bones.”

Another old men, very much an Old Testament figure like Pritam himself, approached their well along the road. Pritam recognized Mamaji, Charan’s uncle, an old friend whom he had not seen in many months. “Sat Sri Akal!” he called out, chuckling.

“Sat Sri Akal, maharaji,” Mamaji called back. “Kya hal chal hai? Are you well?” The two old friends shook hands and Mamaji oat down on the canal bank with a sigh while Pritam went back to his place at the crusher.

“There in Hissar district where I live now we sometimes sow desi wheat.” Mamaji said. He had to raise his voice as the two of them were quite far apart and the crusher groaned and the bullocks’ yoke creaked as the animals went round and round.

“Because we can rely on rain,” Mamaji went on. “We have twelve acres without irrigation.”‘

“What about sugar cane?” Pritam asked.

“I have a good deal of that. I don’t have an engine but I have a camel. When we came and took possession of the Moslem lands, let’s see, can it be twenty-three years already? – we had twelve acres of good, lash sugar cane and there we didn’t use to grow cotton. Sugar cane was the main thing in Bahalpur district.”

“If it’s a wet day, we just can work the crasher. This raas gets soar. Yesterday it was like deep winter here.”

“It’s like winter of course, but in Ludhiana there’s so many mosquitoes already.” Mamaji complained.

“There was a procession in Ludhiana yesterday I heard.”

“I didn’t see it. I came at noon. I stayed with a cousin of mine. He’s an overseer and lives in Modeltown.”

“I heard there were a lot of tractors of our Sikhs in the procession because the government may impose income taxes on farmers.”

“In Bikaner, we had a flat income tax of five hundred rupees on twenty-five acres each year.”

“There is also some tax in Kadhur, I’ve heard.”

“It’s not that direct tax. It’s a hearth tax. Some of those tax collectors eat it up themselves; they just make fools of as.”

“Indira Gandhi will drown the boats of the Jats if she imposes income taxes,” said Pritam. “They have already imposed in Rajasthan.”

“Did I feel a rain drop?”

“It’s only that one small cloud overhead. It will go away.”

“We are not salt that will melt away,” said Pritam.

“Those tax collectors will go on scratching round your houses,” said Gurdev while stoking the fire.

“Your raas bucket is full,” observed Mamaji.

“Yes,” said Pritam. “Let the boy take a round with the bullocks first. We’ll stop at this side.”

“All the gram fields have vanished since the last time I was in Ghungrali,” Mamaji said. “In our area, there’s really a big crop of grams.”

“If they’re there, they’ll come here also. Previously people used to plant them in cornfields. I had two or three acres over there. We sowed grams. They were about twenty-five maunds. Boy, bring some more canes, would you?”

“We used to feed grams to the cattle. Sometimes they didn’t eat anything else. I see Charan is making gur today also. He has that diesel engine.”

“Yes, they’re over there.”

“These days bullocks bring very high prices in Hissar.”

“This side of the country they’re cheap,” answered Pritam. “It they’re not really good bullocks, they don’t fetch good money.”

“Like my own fine white bullocks can fetch two thousand rupees. Ours are three years old.”

“These you see are four years old,” said Pritam.

“My brother just brought-one for two thousand and sixty rupees.”

“Ah.”

“The camel is best for crushing sugar cane,” Mamaji said. “O, Boy, you have broken that rope.”

“You should have tied it nicely,” scolded Pritam. “You just do half things. Now it is all right.” Silence returned from some moments with only the sound of sparrows chirping. “These days camels are cheaper.”

“Camels in Bikaner are very dear.”

“Yes that side they are. Here, there are no Persian wheels any more.”

“Yes,” Mamaji agreed, “now camels are not sold here in Ludhiana district. In the old days we had beautiful saddles for oar camels. These days if a man comes riding by on a camel, people don’t like it. They expect everybody to have a tractor or a motorcycle. We had a saddle one time that cost as eight scores of rupees. We made the floor end rug in our own house.”

“We bought a saddle from Maghiana one time. Even if you put it under a bullock cart it wouldn’t even jerk. It was so nice. If you are once on a camel with a proper saddle it looks like you’re riding a horse. “

“Heh-heh-heh-eh.” Mamaji laughed, ending in a coughing fit.

“There are few persons around here who have not yet started crashing their sugar cane,” Pritam said.

“Sadhu’s daughter, Surjit, has only started. They bought a new gar pan from khanna. And one of the old ones they mended. Charan took them the crasher from here. Let’s see, today is the third.”

“Charan went on the 27th. It was then that we sent the crusher.”

“Yes, I know. The days pass so quickly now.” For some time neither spoke and the silence around the two old friends was like a tomb, as though the air were dead too. The old men sat silent, thinking.

“When we used to make white sugar there was a great hue and cry that there would be taxes on the land and this and that,” Pritam reminisced.

“Yes. White sugar is more expensive and you really can’t compare it with brown sugar. Nothing is better then gur.”

“Is Charan bringing in hay today?””

“Yes, he is just carrying two bales in the cart. He has no place to put it at the barn.”

“He should make a storeroom.”

“They must have spent three to four thousand rupees on that barn. My guess is about one thousand rupees on labor and the rest on material and lumber.”

“You know Sadhu mortgaged three acres in Bija to pay for it.”

“He mortgaged three acres in the old days in Lyallpur also.”

“Yes, do you remember how he would go here and there, gossiping and doing nothing. There were so many like him in those days. We used to call them the safe posh, those in white clothes. They used to bay hay from as and seeing as, they too began to work hard with their hands. Some of them made fortunes. Ah, if a man without enough land wears white clothes he will do badly. We also want to wear white clothes, but we can’t afford it.”

“But Sadhu is a clever man. Look how he brings all these machines from the university to do his work.”

“Yes, times have changed. Now cleverness is almost as important on a farm as hard work. But it is Charan who saves that family. He would be a very good man if he didn’t drink so much.”

There was a sound of barking. “O,” Mamaji called, “look! That dog will attack Sarvan.”

“No, no, he hasn’t attacked him. He is chasing that bitch.”

“Ah, yes, it was a bitch he was after.”

“In Nagor,” said Mamaji, “this time of year was always cheap for bullocks.”

“If Nagor was cheap, why was labor always so expensive?” Pritam asked.

But Mamaji was lost in his own memories. “Yes, it was every month a cattle fair in Nagor. But the biggest is in Hissar these days.”

“There was one person who used to go to Hissar.”

“Who, who used to go to Hissar?” Mamaji asked. Pritam stopped to empty the bucket of raas. “Put it here,” he told the boy.

“There were some foreigners in Hissar,” Mamaji said. “They won’t take as to America. Why should they take us? A person took seven thousand rupees from me one time promising to take me to America and he was really a thug. It was all a swindle. Because he never took me. We told other men not to believe him but the foolish didn’t believe us.”‘

“I’ve heard it costs three thousand rupees on fare,” Pritam said.

“Another man sold his lands to go to America. He sold one piece for seven thousand and told his father-in-law, ‘You take care of the fields and I’m going to America.’ But who was go and who was to take him? The poor fellow remained there, losing his land.”

“It is enough only if we fill our bellies day and night. There’s no money in farming.” Pritam sighed. “There came an Englishman in a car one day. His tire was punctured on the Grand Trunk Road. I was coming on a bicycle. It was sunset. I was also very much tired. There were two of them. One was his wife and the other this Englishman. He started mending his car so I also stopped to watch them. There was a big crowd of young men bothering them. He took oat a revolver and told them to ran away.” Pritam chuckled. “They never looked back, those brave young men. They had been looking at his wife. I remained sitting on my bicycle. He said, ‘We’ll put your cycle in the car and you come with as to Khanna.’ So he gave me a lift. I sat comfortably in that car. The Englishman had traveled a lot and could tell a bad man from a good man. Shabash, my son that is good you have brought more canes. The raas we used to take in Lyallpur in the summer months you can’t compare this raas to it. It is very warm today. “

“It will rain, don’t worry. What to say of warm.”

“Have you prepared cane for crushing, Mamaji?”

“No.”

“That’s good. There surely will be rain. It’s too hot today.” Pritam’s eyes looked far across the fields. “You see that fire coming from the earth? It shows there will be rain.”

Pritam knew the names of all the wild flowers, animals and stones. He could tell the age of a buffalo or bullock that first would come the milk teeth, then after two and a half years, two new big ones; after the age of three two more in six months and another pair after the four and a half years of age. Pritam said you could put a bullock under the yoke after it started growing its first two big teeth bat that between the age of five and six it was in the prime of life, even though it was good for labor for another six years. Bullocks, like people, he said, can no longer walk nicely and lose their teeth when they get really old.

Looking at the sunset, at the moon, or hearing the cry of certain birds, Pritam could tell what sort of weather it would be the next day. Whenever the bambiha bird started chirping, Pritam would say. “It will definitely rain tomorrow.” And indeed, it was not only Pritam who was so wise. Charan, Mukhtar, Dhakel, Sindar, Gurdev stoking the fire, Scooter cutting his oats, and all the villagers, generally speaking, knew as much as he did. These people did not learn from books, but in the fields, in the jungle, on the canal banks. Their teachers were the birds themselves, when they sang to them; the san when it left a glow of scarlet behind it at setting, the very trees and the grain of the fields.

Suddenly Mamaji remembered a local gossip. “O, that boy, Surjit’s son-in-law. You know what he did? They were drinking inside all day. When they came out the air went to his head and he turned mad. He lost his balance of mind and he’s still not all right. I advised them to take him to the hospital and get him some electric shocks. But they were saying he has some outer spirit in him. They were drinking all day inside. In the evening he came out. The air got into his brain and he’s still like that. He doesn’t speak. He sits all day without talking to anyone. Not attending his fields or moving his limbs. His parents say he has some mysterious spirit in him.”

“There was a person from Budwar,” said Pritam, remembering. “He was kin to my uncle. He was a very well educated, clever person. He went to America and he didn’t return for sixteen years. When he came back he was very famous but blind also. He met his mother who started weeping, seeing him blind. ‘It you weep I won’t let you see my face’ the boy said. ‘It is my destiny.” That boy came back after sixteen years.”

“Yes, some people tarn like that when they go there to America.” Mamaji sighed. “A man from our village came back after many years. Nobody could recognize him. Only I could recognize when I looked into his eyes.”

“In fact that man ran away from America. He was hard up there.

“He told me, ‘When you were a little child I used to play with you. You are my sister’s son. You, don’t recognize me.’ You see what fate makes of a man, Pritamji. What he was and what he became.” Mamaji again sighed. “Another man from our village, he was very sturdy. He used to go and take part in all the wrestling bouts before he went to America. He came back after six years. Now he’s running a big shop in Hissar. He was of my age. He brought back good money with him and, late as he was, he got married and last year he was blessed with a son. Imagine, he was of my age.”

“These are the little jokes of God.” Pritam said solemnly. “Nobody has any power over it.”

“O, I forgot what I was talking about,” sighed Mamaji.

“Ah,” Pritam, sitting at the crasher, was reminiscent again. “I was a small child and once a man who was a wrestler had a bout with a person named Ram Singh; when the match started Ram Singh just, took that professional wrestler on his shoulders and threw him down.”

“Ah, I remember Ram Singh.” Mamaji said, brightening up. “Two men were wrestling one day in our village in Lyallpur. Sturdy and strong. His sisters came to know that Ram Singh was wrestling. They got angry and one of them came and hit Ram Singh with a shovel. Ram Singh left that man and gave his sister three strong slaps, saying ‘Why do you worry? We are just playing.'”

“Ah, Ram Singh. Once he was bringing cane from the field and he told his women to beat some corn to get grains. He said he was going to wrestle. But his women, five or six or seven of them, started beating him up instead. But you know, he was never thrown down by anybody.” Pritam chuckled. “My grandfather used to tell me if I was naughty that he’d go and bring Ram Singh from Ludhiana. Poor Ram Singh. He has been dead now, these many wars. Did you ever know Babu Chapria?”

“No, I didn’t know him. There is a man in Bikaner who was deaf and dumb but he held the crown of Punjab for wrestling.”

“Do you remember that person named Ishar. He weighed five maunds.” Pritam’s mind wandered off as he stopped to arrange the pile of cane by his side. “It is close and hot today. There will be rain.”

“Now God is after our mustard and grams in Hissar.”

“Why? Do you think Ire’s not after our wheat? With these thundershowers it goes down and becomes shaky at the root.”

“You used to have another pair of reddish-brown bullocks, Pritam.”

“One of them is dead now. He was swift.”

“Bullocks work without food.”

“For a time. But if you don’t give them good food over the years, they don’t work nicely.”

Pritam worked in silence for a time, then he frowned. “When we first came here the people from Bhambadi would tease as because we wore white clothes. They told as, “You only wear white clothes. You are not good farmers. Now we have shown them.”

“When we started sowing wheat in Hissar, the people of that area would come and quarrel with as. ‘You fools.’ they would say, ‘you will starve. Why don’t you sow gram and mustard?’ That first year we got two hundred maunds of wheat and how everyone was praising as then. Now they are all growing wheat too. They are bad people in our area, worthless. They don’t work hard, really. So that’s why they never tried wheat before. Now they’ve learned. Now I’m running for a piece of land and going to the courts in Jullundur every third day. This area is only half so good. If you go there you’ll see the wheat standing as high as a man’s head.”

“Ah, that is the old kind.”

“You still work as hard as ever, Pritam. These youngsters can’t beat you.”‘

“When we came from Pakistan, how long ago it seems. One person, Wiryam, he died only eight days after we reached here. He brought my children here for me. I was left behind with the bullock cart. He brought the children and then died eight days later. He was like a god for us. Another of God’s jokes.”

“He makes them sometimes. I’ve noticed it before.”

“There was another person also, a real budmash, a bad character. Where he is now, I wonder. He killed one Telochin who was an even bigger budmash. He’s now in Jagraon, I think. You, remember there was one person, Alah Singh, he used to say, ‘Every crippled and disabled man has to fall back from the wagon train to Jagraon town.’ So now everyone of the budmashes has ended up settled in Jagraon instead.”

“There is one Atma Ramdah in our area. He is an eye specialist. Some days back bandits caught him and asked him to pay ten thousand rupees or otherwise they’ll kill him. The poor fellow had to bring the money. He said, “They aren’t really taking anything from me. I can earn ten thousand rupees in a month.’ There were three dacoities this month in Batinda district. Bandits caught two more persons and charged them ten thousand rupees and fifteen thousand rupees.”

But Pritam was not following the other’s words. He was thinking about the mysterious ways of God. “There was a man from Peshawar in the old days, one Bapa, I was thinking of him.”‘ Pritam said. “I met him once not long ago sitting on a road crossing. He was sitting there penniless and he asked if some bus wallah would give him a lift. I told him, ‘You can’t go on a bus nowadays without money.’ He had been very rich in the old days. In 1947, he and some other men deposited seventy thousand maunds of wheat in a princely state which bordered oar village only six miles away. When they demanded it back the prince refused to part with even a single grain. Ah, well, most of the others to whom the wheat belonged were killed coming south.” Pritam rose and stretched. “Older people like me have joint pains.”

“It’s the greed of work,” admonished Mamaji. “You are doing your work and you’re so greedy to get it done you don’t pay attention to the hot sun.”

“No, my friend,” said Pritam. “Our life is easier now. If people go on minding their own business, the villagers here in Ghungrali can become very rich. We’re getting rich day by day, there’s no doubt about it.”

“Are the hard times really over?” Mamaji asked.

His old friend thought a moment, then said, “How can we tell?”

The Mela

The day of the mela arrived; it was a bright, clear, joyous April day. From early morning bullock carts and tractors piled with people and bicycles in two’s and three’s and four’s were moving furiously along the road toward Jarg; there was a jingle of cart bells, the pup-put of tractor engines and a flow of pink, yellow and green turbans along the country road. In the dusty luminescent sunshine the crows were cawing from the neem and shisham trees, disturbed by this unusual stir and bustle and the sparrows sang unwearyingly as if rejoicing that there was a mela at Jarg.

Charan and Mukhtar, dressed in clean white shirts and pale yellow and blue turbans, joined the traffic on the road, Charan driving the tractor, Mukhtar on the shiny red fender beside him and a crowd fall of men and boys in the trolley behind. As they left Ghungrali a man came running alongside them, shouting, “Take my child to the mela.” “We are leaving the trolley there,” called Charan. “The trolley won’t come back. How will he get home?” called Mukhtar. Another man came running up and jumped up on the back of the trolley as it moved along, shooting, “We have been ransacking the village for you.” Charan laughed, “O, how mach fine will you have to pay now? I have already told you it will cost you a bottle to go to the mela.”

Ahead in the road Charan’s friend Prit was running with his bullocks, training for a cart race. Charan roared with laughter and shouted, “Show as your speed! Till the path is clear, just show as your speed!”

As they drive along in the splendid morning, Charan is in a good mood and shows Mukhtar a long sear on his ankle. “Once I was going up to the top of the house with a ladder and a rang broke.”

“There was a brick sticking out right at the corner and it gashed my leg; six inches long and about two and a half inches deep was the wound I got. I didn’t say anything to anyone but went straight to the doctor. I told him, ‘O, I’ve hurt my foot a little.’ He took nine stitches. Everyone gathered around with hot milk. After six or seven glasses, I wanted liquor instead. The doctor said they would have to carry me home on a charpoy. But I said, “No, you don’t. It looks funny to me to be carried that way while I’m alive.” Charan laughed. It felt good to be going to the mela.

“Ah, look,” cried Mukhtar. “They are going on the cycles in three’s.”

Charan accelerated and caught up with a cycle, reaching down with his long arms and palling a bottle out of the rider’s shirt with a great roar of laughter.