Part Two: The City

A study in two parts of the human impact of agricultural change and urbanization in the Javanese village of Pilangsari and the city of Djakarta

Simprug

“You are millions…

But we are countless…”

Aleksandr Blok

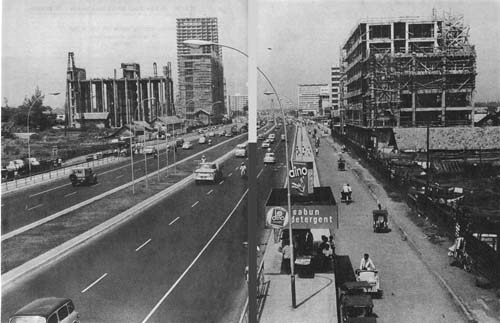

In the heart of Kebajoran Baru, the richest and most aristocratic suburb of Djakarta, lies a large, low, swampy hollow which for most of its existence was planted in rice. Wet and steamy, sometimes flooded waist-deep by monsoon rains and too low to catch the cooling breezes from the Java Sea, the hollow for many years remained an enclave of green, pastoral countryside as the modern suburb, with its big, solid bungalows standing in their leafy, spacious compounds, grew up around it. Then, during Indonesia’s Moslem rebellion of the fifties and the population pressure of the sixties, as the trickle of job-seeking Javanese peasants into the capital city became a raging flood, a sprawling shantytown of densely-packed wooden and bamboo huts began spreading down the sides of the hollow, in time forming a community of several thousand inhabitants which came to be known as Simprug. It was almost hidden from view by rows of shops which faced Sinabung Street, a curving paved road which formed the hollow’s northern and western boundaries. Only the occasional glimpse of a teeming alleyway and atap roofs reminded the residents of Kebajoran that the community existed at all. It was completely cut off from the city’s water, electrical, sewage, garbage collection or educational systems and, as the years went by, Simprug became a little world of its own, a world of little lanes snaking through tightly-packed huts of bamboo, salvaged wood or beaten tin cans. Some of the huts clung to the hillsides and could be reached only by endless little stairways carved from mud, down which waters rushed in the rainy season, scouring away rubbish and dirt and pouring sometimes into the shacks themselves. The alleyways were always crowded with skinny chickens picking in the dirt, women washing and preparing food, men smoking or conversing and multitudes of children.

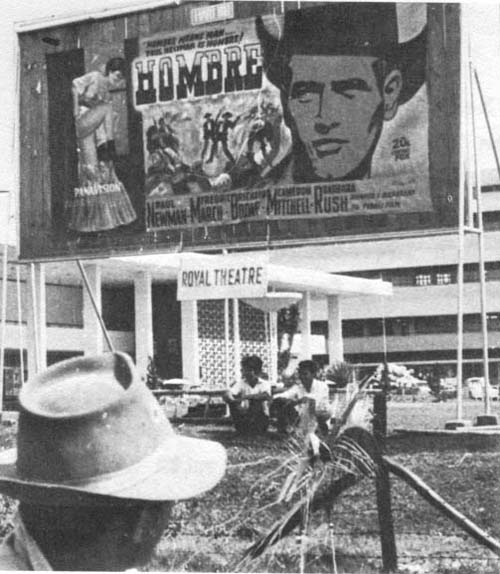

Yet one only had to emerge through the row of shops and cross Sinabung Street to enter the almost deserted, tree-shaded streets of Kebajoran Baru, with its handsome two-story white stone or plaster houses set amidst neatly-trimmed lawns and beds of marigolds, roses and bright red kana flowers, and every variety of tropical tree: the white-blossomed Cambodia, fiery red Flamboyants, groves of whispering Tjamara trees, thickets of bamboo and pink, lavender and orange bowers of bougainvillia. These houses and gardens, especially those nearest the kampong (literally, a village; in Djakarta, a slum community of bamboo, atap huts) as Simprug was called, were protected by high, barbed-wire fences; some, of them had been strung with coils of concertina wire and floodlit and guarded by uniformed men at night, resembling military encampments. But few of the houses were hidden from view and in the evening the people of Simprug could go for a stroll and look into the picture windows or the open terraces and see the draperies, rugs, television sets, book shelves, vases of flowers, gleaming silver and crystal on the tables and a way of life that seemed infinitely luxurious and refined, even if rather lonely and joyless. Some of Simprug’s inhabitants worked as chauffeurs, gardeners, guards, cooks, chambermaids or laundresses in the Kebajoran homes. In this way, sometimes it was the man of the newly arrived peasant family who grew sophisticated in the ways of the place, while his wife, like Husen’s, might be confined to the slum and remain largely innocent about the rudiments of urban living. Sometimes it was the wife, in service to a rich family, who first saw how the rich lived, what food they ate and the clothes they wore. And then in their little huts would appear a white cloth-covered table with a vase of artificial flowers or a framed watercolor or two on the walls. Many of the Simprug men were employed as construction laborers and cement and stone and paint was stolen, not only for cheap resale within the kampong, but to improve the facades of the houses so that in some of the alleyways one might come upon an impressive stone porch, gaily painted doors and window frames; there was even a picture window or two.

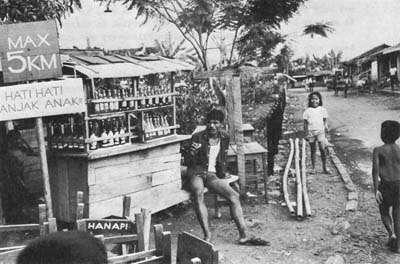

The shops along Sinabung Street supplied the basic needs of the kampong, grocery stores, little restaurants, a betjak stand, tailors, a baker and a barber shop, so that many of the tenants, especially those from the villages, seldom left the immediate neighborhood except to work; almost all of the wives were strangers to most of Djakarta. For a few pennies one could buy sate, a piece of fried mutton on a skewer stick; a coconut and lentil porridge, ice cream soda, coffee, tea, iced beer, rice, boiled eggs, fried chicken, sweet cakes, a pink lolly drink, roasted peanuts or peanut crisps, shrimp cakes and vegetable soup. The grocery shops sold dried fish, lentils, beans, dried peas, potatoes, onions, eggs, noodles, rice wafers, ketchup, coconut oil, kerosene, matches, tea, soap, mosquito repellent, noodles, cigarettes, apples, bananas, papayas, soap, combs, handkerchiefs, tooth brushes, toothpaste, little vials of perfume which men used to rub on their cigarettes or their upper lips, paper, ballpoint pens, notebooks, sugar, flour, rope, lamps and candles.

Many of the vendors had little moveable bamboo pole shops. At one of these a brush salesman sold enough merchandise to fill a storeroom: brooms, wicker laundry baskets, tin tubs, long-handled brushes, shoe brushes, whiskbrooms, hairbrushes and every other imaginable kind.

Sometimes there would be a cheap sale and the hawker’s voice magnified by a loudspeaker, would echo through the market, “I’m not a seller. I don’t sell anything here. I just give you prizes. Who wants to try? In all these packages are free gifts. All you have to do is…”

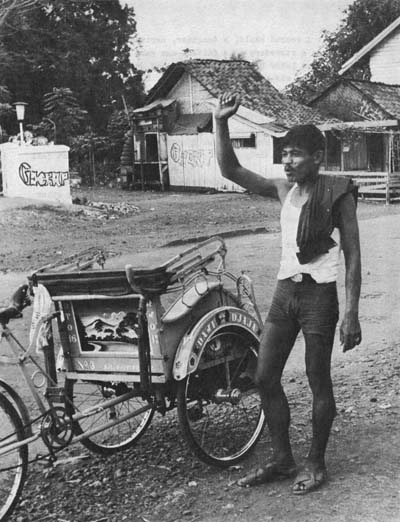

Husen and Karniti had moved into Simprug six months earlier. For Husen it meant pedaling his betjak nearly an extra three miles, usually without a fare, to the Hotel Indonesia and back returning home every night at two or three along dark and deserted Djalan Thamrin.

But he had wanted Karniti to have a more pleasant environment than the denser, filthier slums nearer in. As a betjak man he roamed freely about the city but Karniti was confined most of the time to the little shantytown. The night they returned from Pilangsari, snaking their way in the narrow alleyways past children playing ball – it was safer than the streets – women queuing up at the water pumps or calling to each other as they took in their laundry, and street vendors hawking their wares. Husen felt he had forgotten how crowded it was along the canal. Wooden toilets had been erected on stilts and a few people were squatting there visible to everyone. Along his lane garbage had been thrown in an open pile; no one seemed to collect it and Husen watched a black rat dart out of the refuse and then run back in again. But on the doorstep of their room, Karniti’s two cats were sitting, waiting, looking hungry and woebegone. As Karniti had feared, the inside of the shack they shared with another family was in a shambles: beer bottles and old newspapers were scattered about and a chair lay overturned. Without changing her clothes or another word, Karniti took a broom and started sweeping. Within minutes the place was in order. The room had been divided into three cubicles with bamboo partitions: a bedroom, a hallway for cooking and a living room. There was a big bamboo bed, an old cupboard, a primus stove, some pots and pans and dishes, a kerosene lamp, pillows and blankets, a water pail, and ten glasses. Karniti quickly unpacked her own batiks, jackets and underwear and Husen’s long-sleeved white shirt, his second pair of long trousers, six pairs of tight shorts he wore for work and six slip-over cotton jersey shirts, as well as a green windbreaker jacket and their toothbrushes and her mascara, lipstick, powder and perfume. Husen opened the three small windows in the living room that looked out on the alleyway and set about repairing the latch on the battered front door which someone had broken in their absence. Karniti scrubbed the cement floors so clean one could sit on them, covered the living room table with a clean white cloth and set three wooden chairs with plaited plastic seats around it, hung a silk print of an Arabian desert scene on the wall and prepared Husen a plate of cookies and glass of sweet black Javanese coffee. “You are a nice wife, Kar,” Husen grinned. He was aware that Karniti was an usually good homemaker.

Karniti laughed, happy to be in a household of their own again. She joked, “Maybe you want to take a second wife. Keep me to cook and clean the house.”

Husen laughed and reached out and slapped her bottom. “Maybe I want ten wives.” Then he added seriously, “No, Kar, I don’t want to marry another wife. Two-by-two, that is the best way in life.”

Within a half hour of their arrival, Bibi, Karniti’s aunt from Karanggetas, who lived on the other side of their shack, stuck her head in the doorway. “So you come back from the village again? How long are you going to stay this time, Kar?”

“I don’t know. Maybe long time.”

“Very good there? Many wajang and drama over there, Husen?”

“No. not much now. Before when the rice was harvest, there were many parties.”

“You know I have family not far from Pilangsari,” Bibi said. “My sister is in Wanasari.”

“You should go back when the mango season comes. There’s a lot of parties.”

Bibi sighed. She was a gaunt disheveled-looking woman in her forties. She had one son, a thirteen year old by a former marriage and was now living with a betjak driver of her own age. She was an old timer in Simprug, had lived there almost fifteen years, never went anywhere else in Djakarta and only visited Karanggetas once a year at New Year’s. “I almost never leave the kampong any more. I can buy everything I need here. You know Husen, before I was a maid and got around more. But now no job,” she sighed again. “More and more people are moving in all the time and they come from all parts of the country, especially on the south side of the kampong over by the road. It’s getting very crowded here. Not like the old days.”

Bibi’s husband, Kasum, joined them, “Hey, Husen,” he said, shaking hands. “I see you pasted newspaper on your walls already. If you want to paint it in color don’t buy Alkarim but imported paint. It comes on very good and doesn’t chip off. One can is only 1,300 roops. My friend has a couple of cans he’ll probably sell you. If you buy in a store it’s about 1,700 roops a can,” Husen assumed the paint had been pilfered from work.

“No, that’s too much,” he said. I don’t want to spend too much on painting. I can buy Alkarim. Never mind. If I have the money.”

“Like it is now is fine,” said Bibi. “Maybe you want to make it white?”

“White is best,” Husen said. “It makes the lamplight brighter. It’s good.”

A little boy of about six or seven joined them and pulled at Kasum’s shirt. “I want to sleep, uncle.”

“Waiting short time,” Kasum turned to Bibi, “Shall we take this boy and go home?”

“No, no, no, no,” the boy cried. “I want to stay with uncle.”

“It’s my sister’s boy,” Kasum explained. “He’s staying here with us.”

“Oh, in the village life is very, very good,” Kasum said in a weak voice. He was a weary-looking, wiry little Javanese with a worn down, deeply-lined face. “Many people sit around like this. If you are a village boy Husen, you always have good stories.”

Husen laughed. “No, I know only a little. You like one now? I can give one only. It is short.” He related the story of the monkey and the turtle. When he came to the end, Kasum said, “Oh, you have stories and tell them good, Husen.”

“If I am not forget, okay, can tell many stories. But sometimes forget.”

“Husen, I watch you,” Kasum went on. “You not yet a long time stay in Simprug and you are very friendly with other people, so many know you. You stay here only a short time but already you know more than me. And I’ve been here almost fifteen years. Maybe in your village there is more people than here, more friendly people than here in the city.”

Husen smiled. He felt sorry for Bibi and Kasum; they seemed to personify what happened to people if they stayed too long in the city.

“I am always looking for friends,” Husen said, “I think many, many friends in Djakarta is good.”

“You like to stay here a long time? Okay, if play rummy very quickly make friends.”

After Bibi and Kasum left, Karniti, who had been chattering cheerfully with Bibi, abruptly sat down and held her face with her hands, “Husen,” she said, “it’s better you make food for yourself tonight.”

“You are ill?”

“You must be hungry. Can you make it yourself? I’m feverish.”

“Don’t take a bath because it’s dangerous. If you have a fever you should not get wet. I’ll bring some water from the pump and you can wash off. Do you like some ‘Tiger Balm’ medicine?”

“No, not like.”

“Please take a pill, an aspirin with some hot tea.”

But Karniti was emphatic. “No, no.”

Husen busied himself in the kitchen and prepared rice, an omelette and cut some chilies for nasi goreng. Karniti was now lying down on their bed and he brought her a dishful. “Do you like to eat, Kar, all right?”

“No. no.”

“But, please, Kar, you must eat rice.”

“Please you buy some ice. That’s all I want.”

“You. That is very dangerous. You cannot drink ice. Please, if you like, you must drink many, many hot tea.”

Husen decided not to drive the betjak that night. He had picked up the keys from the stand on their way from the bus but now took them down the alleyway to a neighbor who was out of work and told him he could use the betjak that evening.

“Have you any rice?” the man asked after thanking him for the use of the betjak. “I have no money.”

“No. My wife is ill. Maybe if she is well, maybe, please you can come and eat in my house.”

“All right. I’ll wash the betjak before I bring it back.”

The next morning, Husen rose early. Karniti was still feverish and stayed in bed and he spent the morning cleaning the house, cooking and washing clothes and dishes. By noon he too felt a little feverish and went to sleep by Karniti’s side, not waking until he heard the evening prayers coming from the mosque. He jumped up and went to bathe in the canal near Sinabung Street, then came back and dressed in his betjak clothes.

Karniti stirred. “Kar, you rest, I want to drive the betjak.”

“Please don’t go,” she murmured.

“I must, Kar. We have no money to eat tomorrow.”

Husen put his head into Bibi’s door to ask her to watch Karniti. But she was sick too, her head wrapped in a towel, her eyes watery and sneezing. “I have a terrible cold,” Bibi groaned. “Where’s Karniti?”

“She’s ill too. Maybe we’re all getting influenza.”

Bibi sneezed again, looking even more miserable. “Where is she?”

“Inside.”

“If you’re going to everywhere, Husen, Karniti is afraid. Maybe you’ll have trouble in the street, maybe an accident. She doesn’t know. She doesn’t look well, Husen. Why didn’t she stay in the village?”

“She vomited tonight.”

“Oh, maybe she has a baby inside her that wants out. Send her to the dukun tomorrow, Husen.”

It took Husen more than half an hour to pedal to the hotel and when he arrived he already felt tired and a little feverish. He parked his betjak and climbed in resting. None of his usual friends seemed about, Tjasta, Tjasidi, Eddy or Jusup, all youths from villages close to Pilangsari. Nothing had changed at the Hotel Indonesia. Several betjak men squatted around a portable soup kitchen. There was the sound of a band from one of the top floors. Vendors moved by, yellow lights flashed as cars rumbled past, there was the sound of traffic. One betjak driver seemed sick at his stomach and sat with his eyes closed, his arms folded across his middle. Maybe influenza too, Husen thought.

He had no fare until midnight. He was thinking so much of life is spent waiting. The night seemed to grow sinister as time passed. Darting figures in the shadow down Djalan Thamrin, low murmurs of conversation. The headlights of speeding cars. It was getting late.

“Hey, mister! Where are you going?”

All the drivers moved forward eagerly, pushing their betjaks toward an elderly white-haired European who was approaching down the entranceway. By some stroke of luck he picked Husen’s betjak and told him to go to the Ramayana City Hotel, about half a mile’s distance.

He was a kindly old American and on the way asked Husen, “What’s the matter, son? You’re not looking well.”

“Because my wife is ill, tuan,” and Husen told him about returning from the village and that there was influenza in his kampong. When they reached their destination, the old man, to Husen’s surprise, pulled out a traveler’s check and presented it to him. It was for twenty U.S. dollars.

“One rupiah I not eat, tuan,” Husen promised his benefactor. “I give it all to my wife.” Husen hurried back to cash the check at the Hotel Indonesia but learned at the desk to his dismay that he needed the man’s passport number. He pedaled back again to the Ramayana City Hotel but learned from the desk clerk, a wavy-haired Balinese, that the guest had already retired and could not be disturbed. He was flying to Singapore the following morning at five a.m. Husen thought of spending the night in his betjak in front of the hotel but feared he might oversleep; he was also worried about Karniti. If he didn’t come home all night, what would she think?

In desperation he appealed to the hotel clerk once more. The clerk, who said he would still be on duty in the morning, agreed to give Husen five thousand rupiah in cash if he endorsed the check over to him. Husen knew the check’s real exchange value was seven thousand five hundred rupiah but he agreed. He was so relieved and happy as he pedaled home, he hardly noticed the distance. Five thousand rupiah meant he wouldn’t have to leave Karniti until she was well. With care they could stretch it out for two weeks, or even longer. He could buy some blue paint for the door and window shutters and some Alkarim to whitewash the walls. Simprug wasn’t like Bongkaren, where people were afraid to show if they had a little money. In Simprug, everyone wanted their house to be nice. He might even buy a guitar, he thought, and then remembered he still had his son, Rustam’s circumcision to pay for.

In the morning, Husen awoke early, listening to the voices of his neighbors; so thin were the bamboo walls and so densely-packed the houses, it sounded as if some of the voices were in the same room with him.

“In our family,” a woman said, “the man is number one.”

“That’s all right,” said a second woman. “I don’t mind if the man is kind with me.”

Through the kitchen wall he heard a policeman who lived behind scold a crying baby. “You don’t be cross, my girl.”

“Never mind,” said his wife. “She is only a baby.”

Karniti still slept and Husen, tying on his sarong more securely, stumbled out into the living room and lit a kretek. Bibi stuck her head in the door.

“Oh, Husen, already get up.”

“Yes, because I want to take a piss,” he growled.

Bibi was used to men being ill-tempered in the morning. She pushed the door open a crack wider. “Are you still sick now, Husen? Is your fever gone away?”

“Yah. I don’t know why I had it. Already I’m here in Simprug a long time and I never got sick before.”

“Where is Kar?”

“In the bedroom.”

“Husen, I know a man with three sacks of cement. You want to buy some?”

“No, because I haven’t money for cement.”

“Very cheap. Maybe he gives one sack for a hundred roops.”

“Tida apa apa. Never mind. If you have to buy in a shop, it may be seven hundred.” Seeing Husen was not interested, Bibi went back to see Karniti.

Through the rear partition Husen could hear the policeman’s voice. “Where is matches?”

“On the table,” his wife replying.

“Yah, yah. Titin, get me cigarette from the table.”

“Get it yourself. My hands are wet. “Quickly,” the policeman’s voice raised, now. “Get cigarette!”

“Please, wait a minute then. Okay here it is.”

Farini, another woman neighbor, stuck her head in the door saying, “Husen, tell Karniti there’s water.”

“Where is?”

“There. The pump is working again. Is Kar already good?”

“Maybe a little better.”

“Where’s my sarong?” the policeman called.

“Over on the chair.”

From the house to the west came another voice, “That’s bad. The baby wet this blanket already.”

Husen opened the door and stood surveying the alleyway and smoking his kretek. A neighbor youth, Kuntio, was washing a Vespa by the pump.

“Where did you go last night, Husen?” Kuntio called.

“Drive the betjak.” “You look sick. What’s wrong?”

“My head is still a little stuffed up. Maybe influenza yesterday.”

“I’m making good my Vespa.”

“Oh, you already have Vespa?”

Bibi brushed past him on her way out.

“She’s still nauseated. You better send her to the dukun today, Husen.”

Husen could hear Karniti stirring in the next cubicle. “Already up, Kar? How you feel?”

But she was already talking through the partition to the policeman’s wife, “Are you last night from the Djakarta fair, Titin?” he heard Karniti ask.

“Yah.”

“Your husband was asking everywhere for you about midnight.”

“Yah, I know, Kar. I know,” came a weary reply.

Husen poured some cold tea from the night before into a glass and drank some to clear his throat.

“He’ll never let me hear the end of it,” the policeman’s wife went on. “I went with my sister, first time out of the house in five months. He’s afraid to let me go anywhere because he thinks there might be a fire here.”

The two women began speaking in whispers and Husen could only hear snatches of their words. “Oh, he looks like his father…” “He never smiles…” “I think the baby’s shirt…” followed by Karniti’s high, infectious, tinkling laughter. “I know the woman who sells them…” “Walking all day…” Then they began talking in mock little girls’ voices and started giggling.

Husen smiled and went off to the canal.

Karniti prepared nasi goreng and a fresh pot of coffee and after breakfast she stood in their doorstoop. Titin, a pretty girl in her early twenties came by with her baby son. “Here, Kar,” she said, “Hold my baby. I want to go to the shop and buy bananas.”

Karniti took the baby and cradled it in her arms, rocking it gently and speaking to it in a hushed voice. “Are you a nice boy? When you are big, you mustn’t be cross. Oh, you are very clean. Like my little boy before.”

The policeman came. “Is that my boy with you, Karniti? Where is Titin?”

“I don’t know. She went to buy bananas.”

“It’s a long time already.”

“Maybe she is going to find her girlfriend,” Karniti suggested, “Because her house is just around the corner from the banana stall. She should come right back.”

“Here, I’ll take the baby,” the policeman said. “You look tired.”

“No, never mind.”

“Back from work, Husen?” the policeman asked.

“Yah. Very nice your son. Ours was like that.” Husen joined Karniti on the doorstoop. “White, like Holland peoples. With a long nose. And big. But he was too hot. Like influenza.”

Bibi stuck her head out her door. “If your little baby had only lived, Kar. It was very pretty. It could be playing with this little one now.”

“When did you get back from the village, Husen?” the policeman asked.

“Three days ago. Okay, very happy to be back in Djakarta. Do you like that policeman’s life?”

“Ah, you’re better off being a betjak man. You are only looking for money passengers. If you have money you can go home.”

“Yah, it is different for the policeman. But every month you can find rice, much money and eat fish and many good foods.”

“Yah, sure, but I must stay all the time in the station and if I want to do like you, going everywhere, I cannot. Okay let’s go, baby. Husen, please you come to my house. Now better I looking for Titin.”

“Thank you, I come later on.”

When they had gone inside Karniti sat on the edge of the bed and told Husen, “I want going to the dukun for a massage. I want to know about myself.”

“Please. Where is? Give me money, Husen.”

“How much?” He had not told her about the five thousand rupiah.

“Two hundred.”

“Where are you going, Dukun where?”

“Just over there. In Simprug.”

That morning a letter came from the village. Husen thought it was from his father, but when he opened it he saw it was from Abu. The student sounded a little discouraged:

“Sometimes the government leaves sprayers, fertilizer and insecticides but because of mismanagement in the village the help doesn’t get to the farmers. There is too little cooperation and too much mismanagement in the administration. If the government gives five sprayers and the people only get four…but I must write about the technical side only. If I talk about kortuptsi here, Husen, it is possible I will not get rice or a place to live. I could become persona non grata. But from year to year it gets better. Perhaps the chief is too old.

Then the letter brightened and Abu reported he had met a beautiful girl, Tarwi, who lived not far from Husen in Pilangsari.

Husen hooted out loud. Tarwi! She was only eighteen and had already had five husbands. The first was only her father’s household servant and the marriage had lasted only two months. Now Tarwi had given up matrimony in favor of singing at wajangs and dramas.

Husen read the passage to Karniti and laughed. “Be careful, old Abu,” he chuckled. “Awas! Watch out! You will be Tarwi’s sixth husband.”

“Her father is rich, Husen,” Karniti answered from the kitchen.

The letter closed with Abu urging Husen to return to the village and farm. “Your father’s is only the primitive agriculture, Husen. Only open the soil and drop the seed. What you need is a mixed economy, maybe have a shop on the road and sell things during the slow times. Your earth is good. All you need is to improve the soil texture and soil structure. Never sell your land, Husen.” Abu concluded by saying he felt very tired.

“Abu should take vitamins,” Husen called to Karniti. “He should exercise and get strong.” And he thought to himself, “No, if sell the land is finish for the farmer and he have not land again. If have not land, garden, life in the village is very difficult.” And he mused, “Maybe if I can ever get capital to open a small warung, okay, very good. I stay in village. Maybe buy mangos or bananas and sell in Djatibarang. If you have 100,000 roops or have four people who all together have 400,000, you can buy many mangoes from the farmers and sell in Djakarta.” And Husen decided not to buy paint but to secretly put the money aside as the beginning of savings to buy a warung, or small shop in the village.

That evening Husen stayed home and did not drive the betjak as Karniti’s fever returned slightly in the afternoon. Instead, after the evening meal, he sat reading aloud to her from a Djakarta newspaper.

“Oh, a robber was shot near the Ramayana Hotel.” Husen always enjoyed a newspaper and puffed on his kretek, absently slapping a mosquito on his leg. “Oh, a student kills his friend. Will get three years in the black house. They were friends of a professor at Bogor. An old Dutchman. He hired one to do it. Homosex. Fifty thousand roops to kill his boy friend.”

Karniti brought in a fresh pot of sweet, steaming Javanese, coffee. “Oh, a Japanese got stabbed in a betjak on Djalan Thamrin. You know, Kar, if I see some men who look like robbers I smile and shout, ‘Hello!’ and I think they don’t rob me. That is my tactics. Fifteen years in Djakarta and never been robbed.”

“Yah, maybe someday you smile and shout and they stab you anyway. You must be careful, Husen. Not going to everywhere.”

A husky youth with high cheekbones and an unruly shock of coarse black hair stuck his head in the doorway. It was Tarman, a fellow betjak driver.

“Hello, Husen.”

“Ah, Tarman, what do you like? Come in. Please sit, down. Have some coffee?”

“You not drive your betjak tonight?”

“Yah. How about you? Are you driving tonight?”

“Yah, am. It’s over on Sinabung.”

“How come you’re out here so early? No business at the Hotel Indonesia?”

“First, I wanted to find you and, second, I wanted to tell you about my boy. I want to take my boy back to the village for to get his pipe cut (Djakarta vernacular for circumcised). But my only pair of pants is dirty and I wanted to go tonight. Can you loan me one pair of pants?”

“Oh, yah. All right. I have. Wait a short time. I’ll go and get.” Husen went to the bedroom where Karniti was already lying down and took his clean pair of pants from the cupboard.

Tarman was very grateful. “Oh, thank you very much, Husen. Because I got a letter from my uncle this evening. I must go quickly to the village. I must go right away tonight.”

Husen: “I don’t know if these will fit or not. Try first. If they don’t fit you can take the ones I have on.”

Tarman: “Oh, I’m sure. I mean you and me are the same size. If I think I want to borrow from another friend, I think I won’t get. All the betjak drivers aren’t like you. You all the time wear good pants and clean ones.”

Husen: “Yah, for me it is custom already. Maybe if dirty pants and shirt, much sweating maybe, not good for me. I must change all the time.”

Tarman: “Oh, yah, your friend, Kanil, he is already working again. I forget the street. If you want to find him, you can go there.”

Husen: “Oh, is he already working?”

Tarman: “Yah.”

Husen: “Before he is one place with me. You can ask him about me and him. If he hasn’t money, I give him. It is the same with him. All the time, sama sama. We were good friends.”

Tarman: “You are all the time easy-going. If somebody’s in trouble, you always help, so I come to you. In Djakarta I always tell myself, if I am this minute want to go back to the village, okay, I’ll leave right now. If time of trouble or dangerous in the streets in Djakarta, okay, I’m not afraid. I can go home.”

Husen: “Yah. This is very important. You must go home because they’re cutting your boy’s pipe. You must be there.”

Tarman: “Before also, if I want to go home, okay, any time, day or night, I go home. From Pilangsari you have to cross the rice fields. There’s a short cut of about ten kilometers. One time I was robbed there. Four men were waiting in the field with knives and I had to jump into the Tjimanuk. Halfway from Tjelang to my village. I must jump into the river because I’m not strong enough to handle four men. My money and cakes got wet and my clothes were dripping wet but I swam across the river. I left Djakarta by bus at three o’clock in the afternoon but didn’t reach Tjelang until after midnight. And so I must go through empty streets and across the rice fields. My money got wet in the river but I could dry it out. I had seven thousand roops with me to get married with. And the river was full after the rains. Very dangerous to jump in. But I thought it’s up to Allah. And after that I am walking along the bank and it gave way and the river flooded into the rice field. Maybe twenty meters or so. By that time I was far from Tjelang but I couldn’t get across so I had to walk all the way back again. I thought, okay, I’ve survived robbers and snakes so I can go back and try swimming across the river in a low place. The water was up to my chest. When I reached my girl’s house finally and knocked and called, “Marmar!” she shouted back like she was really angry. ‘Who is that? Who do you think you are to pound on the door and call out my name at this time of night?’ Wah! She was angry! And I shouted, ‘It’s me! Tarman!’ She recognized my voice and said, ‘C’mon inside. What time did you leave Djakarta?’ I told her the story and she wasn’t angry any more. We got married and now my boy is seven.”

Husen: “When will you get his pipe cut?”

Tarman: “Very soon. Maybe Friday. Are you coming back to the village by then?”

“No.”

“I’m just staying a short time myself. Maybe just a week and then come back here again. Okay, Husen, trimakasih, I’ll go now.”

Karniti, who had been listening to them talk, called to Husen, “Why did you give him your pants? He’ll be gone for a week.”

“Oh, Kar, I think it could be me. Tarman has no money and I know he has no pair of long pants. All he has got are those ragged betjak clothes he was wearing. Maybe someday I could fall down like that in Djakarta and have no long pants. I think difficult.”

Tarman stuck his head back in the door. “Oh, Husen, I forgot. Kanil said with me he is looking for you. They want to have a sampion* match here next week. Kanil wants to know if you’ll fight.”

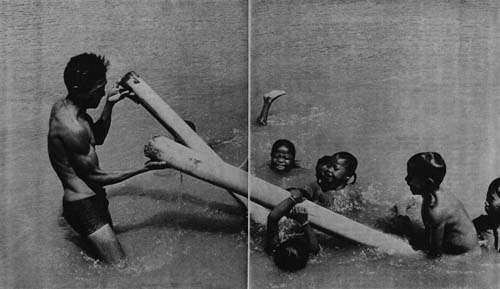

A sampion match is peculiar to western Java’s Tjirebon region. Two teams are paired off, one by one, to beat each other on the ankles with staves; it is rather like a cockfight and anyone who flinches can be hit on the head.

When he had gone Bibi stuck her head in the door. She said she was upset. “Somebody told me my boy got into a fight and I can’t find him. If Kasum comes, tell him I went out looking for my boy.”

Alone, Husen went outside to join some men who were sitting in the cool of the evening on a porch across the alleyway. One of them had a guitar and Husen asked to borrow it, first strumming some chords and then singing a few strange, melancholy Tjirebon songs, his voice sliding up and down the scale from bass to falsetto.

Thousands of stars in the sky

But the moon shines unconquerably

Thousands of girls of beauty

But my love is unconquerableA black cloud covers the sky

Like Armadillo’s broad shield

Take, hear and remember

The moments of our loveVolunteers, volunteers, men and women

Virgins must be cautiousAdiguru is a king of the universe

Narada crowns himself with a basket

Don’t hurry for a divorce

Beware of the life of a grass widow

Then, warming up, he sang a couple of tunes in English he had learned in his schooldays in Indramaju:

Twinkle, twinkle, Little Star

How I wonder what you are

Up above the world so high,

Like a diamond in the sky

When the blazing sun is gone

When he nothing shines upon

Then you show your little light

Twinkle, twinkle, all the night.

“What’s it mean, Husen?”

“Ah. Twinkle, twinkle, Little Star. I am not understand about you. Very high in the sky. Maybe something like a diamond. What you like to hear now?”

Oh, I went down south for to see my Sal

Singing Pollywollydoodle all the day

My Sally Ann was friendly gal

Singing Pollywollydoodle all the day…My Bonnie is over the ocean

My Bonnie is over the sea

My Bonnie is over the ocean

Oh, bring back my Bonnie to me…Dashing through the snow

In a one horse open sleigh

Over the fields we go

Laughing all the way

Bells on bobtail ring

Making spirits bright

What fun is this to ride and sing

A sleighing song tonight.Jingle bells, jingle bells, jingle all the way

Oh, what fun it is to ride

In a one horse open sleigh.

“What’s a one horse open sleigh, Husen?”

He chuckled. “I am not know. Maybe something, and so on and so on.” And he went back to Tjirebon tunes:

Jingling of the lollypop seller

Even though not sold it is offered

The beautiful girl with the waving hair and yellow skin

I know I can’t have her. But I’ll ask.Oh, passing the Pegagan River

I saw that Slijag Village had no chief…

“Hey, Husen!”

It was Muri, a very tall, powerfully-built Javanese in his forties who lived down the alleyway from Husen. He had bushy black curly hair. His forehead was broad and high, and when he grinned, as he almost always did, the skin in the corner of his eyes would wrinkle into crow’s feet. Muri was almost always amused about something, giving him an ironic air. Now he looked sleepy; he practiced sorcery and claimed to have not slept for forty nights, although he went to work every day at his job in the Djakarta mint. Like most Javanese, Muri believed that unless you fast and deliberately deny the body sleep you cannot understand magic and the occult. Back home in the village, Abu, although fasting was forbidden by Islam, once went without eating for five days to see if it would improve his work effectiveness.” Husen, who did not even observe the Moslem month of fasting, Ramadan, when it is forbidden to eat between dawn and dusk, had once gone without food for three days. At the end of the third day, Husen thought, Wah! I’m hungry. And he ate.

But Muri was a serious sorcerer and was believed to have occult powers, even over some of the foreigners who were employed by the mint. Through the thin bamboo walls of his shack, where Muri lived alone, having left his wife in his village, Husen had once heard the sorcerer chanting in a low voice.

As the head of the buffalo hangs down

Stiff as a seashell

May Sujono lower his head as my servant

Bow down as if he were the servant of my penis.

But whatever magic deeds, for good or evil, Muri had ever performed, Husen did not know. But he liked Muri’s joking manner and air of amusement, and he and Husen had become good friends.

“Husen, when you come back from the village? I want to speak with you. Come, we go to your house.”

As they sat down, Husen noticed Muri was carrying a small stone idol in his hands. It seemed to have once been in human shape, that of a man sitting Buddha-like with his hands raised. But it was very old and had been worn smooth and almost shapeless. Husen knew that this was Muri’s djimat (magic talisman) and that like some krises, or ceremonial daggers, and even certain human hair, possessed the quality of magic. Muri claimed to have found it one moonless night in a field, when it suddenly erupted with a fountain of sparks. He said he turned his flashlight on it and the light slowly went out, the last faint ray falling upon this stone.

“Last night this stone had a fight with another ghost,” Muri now said with a straight face, even if he grinned as he always did. “My friends called me – I was outside – and said, ‘Muri, Muri, come here!’ We could hear drum beating in my room where the stone was. ‘Tomtom te tomtom, tom te tom te tom, tomtom, tomtom, tomtom!’ ‘Please, what is, that?’ my friends ask. I went inside and the room was empty. Came outside again and the stone started making the sound of drums again. My friends said, ‘Muri, you take your stone outside tomorrow night. We’re afraid to sleep in the same house with it.’ So, Husen, maybe you want to borrow my stone tonight and I can leave it here.”

“What for?” Husen chuckled. “If I get your stone I’ll break it with a hammer. And if your stone is really a setan or ghost, I’ll die.”

Muri laughed. “Okay, please try.”

Husen took the djimat and a hammer and squatted on the floor, moving as if he were really going to hit the stone.

“Okay, already,” he chuckled.

But Muri was alarmed now Husen might be serious. “No, no, Husen, please. I’ll have trouble finding another one like that.”

“Wah, Muri, I’m not afraid of setans or ghosts. I’m not afraid of this stone.” Okay, leave it here. If it has magic maybe I’ll be like you, Muri. Not much work, at night going to everywhere, not sleep.”

Muri stripped off his shirt, revealing his powerful shoulders and biceps. “Okay, Husen, here’s Titin’s father. He wants to play cards. Bring two friends more and we’ll play some rummy.”

“No,” Husen said. Karniti is sick. You go play cards. I am very tired if I have to wait for you all the time in rummy. I like to play quick.”

Titin’s father, a wiry old man with a brown, wrinkled face, like a walnut, joined them. “Oh, never mind, Kar,” he called into the bedroom. “We won’t play for money.”

Karniti, whose temperature had risen steadily during the evening, called back in a faint voice, “Yah, father, but it is difficult. Once Husen takes the cards in his hand, he doesn’t like to come home.”

A third player had been found in the lane and he too came in and urged Husen to join them, saying “C’mon, brother Husen. Please, if you don’t play where can we find a fourth man? Because my uncle, he will get angry if you don’t play.”

Husen went back into the bedroom. “Wait a short time, Kar, and I’ll make you some hot tea. I want to play cards for a short time. Just across the lane at Titin’s father’s house. We’ll be out front on the porch and you can call.” Karniti murmured something which Husen took as assent. Outside he could hear the murmur of voices, especially Muri’s deep-throated chuckle and he hurried to join them.

A table was brought and once seated, Muri shuffled their cards rapidly and expertly.

Husen began to enjoy himself. “Muri, please, your magic and your setans are helping you to get good cards.”

Muri laughed. “Oh, play only for fun. Not money. I don’t need help from my setans.”

A very old man, the local masseur came in to watch them.

“Uncle, uncle, you have money?” Husen greeted him.

“No, no money.”

“All right, if you have no money, you sit behind Muri.”

“Why?”

“Because Muri is such a fast dealer, he’ll get tired soon. So uncle can massage his shoulders.”

Muri cursed Husen under his breath, “Bohong, Husen. Kurang adjar, sialan!” [Roughly translated, “Damn you, Husen, you have no education; I wish you bad luck, you bastard.”] Husen chuckled, “See, he is tired already.”

“That’s a damned lie. Goddamit, Husen, go to hell. Shut your mouth.”

“Oh, Muri, you are taking a long time shuffling those cards. You looked tired. Please, the massage man is already behind you. If you’re broke I can give you a little money. Here, here’s fifty roops for a massage. Get change for this hundred.”

Muri chuckled. “Husen, okay, if you want to try to play cards with me, okay. Please stand behind me, then you can see my cards.”

“Ah, so slow. I am must wait for you to finish shuffling all night. Better I go to sleep now.”

“Wah! Husen, you must play with the children. Not with the men. You are a stupid.”

Titin’s father joined in the good natured banter. “Oh, please, Muri, Husen. If Muri keeps shuffling those cards all night, I’ll cut his ear off. You must be careful with Muri. He has ilmu (has supernatural powers). Sometimes he has four eyes. Two for his cards and two for yours.”

“No,” said Husen. “Because Muri has magic. All time not sleep, for forty nights. Oh, Muri, please scratch my back. Something bit me and I can’t reach it.” Muri, taking him seriously, reached over. “No, not there, further down.” As Muri leaned over, Husen broke wind and all four men roared with laughter at the success of the old Javanese ruse.

“When you go back to the village, Husen,” Titin’s father said, “after you cut your rice, you can buy shirts in Djakarta for three hundred fifty roops and sell them for five hundred.”

“Yah,” Husen agreed. “It is not difficult to buy things here and sell them in the village. If you have money. One time I bought straw hats in Djakarta for four hundred and sold them in Pilangsari for five hundred fifty.”

“C’mon, Husen,” the fourth player said. “This table is empty of cards. We’ve got three already. You play first.”

For several hours the men played; all the people in the nearby houses could hear the hum of their voices.

“If somebody has the eight of spades…

“All right.”

“Up to how much?”

“Oh, one thousand.”

“Hey, I am first.”

“Who dealt this?”

“Loser deals.”

Near one o’clock in the morning the fourth player, a man from central Java, yawned. “Wah! I am tired.”

The game went on.

“A, b, c, d. Twenty-five for Husen, Forty, thirty-five, five.”

“Okay, please deal.”

“Quickly.”

Muri’s voice. I can close now if Husen will give me.

Husen chuckled. He had taken a “little look” at Muri’s hand and knew Muri was waiting for him to discard the ace of spades. He threw the jack of clubs down.

Muri drew from the pack. “Oh, maybe this time.”

“Wah! Maybe under from you, that card you want, Muri.”

“Noooooo, I’m sure it’s in the deck.”

“How many fingers do you, have?” the central Java man asked.

“Ten.”

“Oh, you bodoh tolol (stupid ass). What a stupid!”

“Why you calling me stupid?”

“Count your fingers. How much?”

“This is ten again.”

“No, twenty, stupid.”

“Oh, you mean counting the toes as well.”

“If ten, okay. You can close.”

Muri drew for the last time. Only three cards were left on the table.

With a shout, Husen slammed down the ace of spades and laughed, “This is for you, Muri!”

“Ah, you are a bastard. You don’t give me.”

“Maybe I was sitting on it. I think you are going to take until sunup to shuffle the pack, Muri. C’mon, don’t take all night.”

“I’m in my village; I play first.”

“All right, all right.”

“Let’s go.”

“Deal.”

After each picked up his seven cards, Husen pretended to knock some ash off his kretek so he could lower his head and glimpse Muri’s cards. He left the burning kretek lying on the floor, then reached down and picked it up again. Muri needed only the deuce of clubs which Husen had in his hand. “Okay, let’s go,” Husen said with mock impatience.

Muri wanted to close. “I’m sure all are less,” he said. Husen teasingly played the six and then the seven of clubs but not the deuce.

This time Titin’s father discarded a deuce, giving Husen three and he played them on the table.

Muri swore, “Wah, a triple three and I have two fours and two fives, both clubs. Husen, you’re crazy. You always give me the wrong cards. Kurang adjar! Sialan! Yah, I’m waiting for you next time. For I know you’re clever about cards.”

Husen laughed.

“If I play all the time with you, I watch my cards every minute, Husen, you bastard. Okay, deal. Please, Husen, try again.”

“Maybe it is I have magic.”

“I understand now about you and your magic. Deal.”

“Okay, please.”

“You’re a clever bastard.”

Husen grinned. “I’ve got 955, only forty-five more so maybe I quit, okay. I like sleep.”

It was after two. Husen shook hands with the other players and went down to the pump to splash water on his face. Wah! Too many cigarettes. As he moved back toward his shack he heard a series of moans and what sounded like terrified gasps. He started to run. Maybe Karniti was having a nightmare. Then he heard a scream such as he had never heard; no one would have thought so small a girl as Karniti could have uttered such a scream. A silence fell over the lane and Husen burst into the house.

Only a small oil lamp lit the bedroom. Karniti was sitting up, her hands to her mouth, staring with wide, terrified eyes at the far bamboo wall, “It’s there! It’s there!” she cried.

“Where?” Husen called.

“There, there!” Husen took her in his arms. “There’s a ghost, Husen. Oh, I was so afraid!”

“I can’t see anything. What is it?”

He took the broom and flayed it around the dark corners of the small room.

“He’s gone! He’s run away already!”

“Oh, already gone. If go away, why you ‘fraid, Kar? I am not ‘fraid with ghosts.” He felt Karniti shivering in his arms and with her head on his shoulder she began to cry. “Before when I am buffalo boy, must stay out in the fields after dark. I not ‘fraid of setans and ghosts.” Husen could hear people calling from the neighboring houses. There were excited voices just outside in the lane. “You wait here, Kar. I want to go out a minute.”

Karniti clung to him, sobbing and gasping for breath. She had been sleeping, she said, and was awakened when the figure of a man dressed in black and much taller than Husen entered the little bedroom. She had instinctively reached out on the bed for Husen, but he was not there. She continued to clutch out for Husen as the setan’s body had closed over hers; struggling, choked with fear and horror, she felt his arms tightly embrace her; the weight of his heavy body, his panting and rasping breath. Paralyzed with fright, it was only when she opened her eyes wide and saw not the man’s whole face but his black, open mouth with pointed, fang-like teeth, that she was able to scream.

“I cannot see; there is nothing there,” Husen kept telling her. Someone started pounding on the door outside, and Husen rose to open it. It was Muri and a dozen or so anxious neighbors. Husen explained what happened. He said his wife must have had a nightmare.

“No,” said Muri. “I also saw him, but I did not know he comes from your house. Like a very big man dressed in black. It was a setan.”

“Are you sure you saw the ghost?” Husen was doubtful.

“Yes, he ran through that alleyway.”

Bibi, pulling a batik around her shoulders apprehensively, was thrilled with excitement. “That girl, Karniti’s cousin, ran away one night while you were in the village after seeing the same setan. He tried to embrace her too.” Bibi rushed past Husen into the house. He and Muri followed her.

“Why? Why?” Bibi shrieked at Karniti, who began to cry again.

“I don’t know,” Husen said. “My wife, she sees the setan. But I cannot see. I don’t know.”

“You must read from the Koran, Husen,” Bibi advised and Husen recited a short prayer.

Bibi sat on the edge of the bed, wrapping her arms around Karniti and gently rocking her as one would a small child, “All right, Kar. Better you come and sleep in my room, get out of this place.”

“No, no,” Karniti sobbed.

“Never mind,” Husen interjected. “The ghost won’t come again now.”

“Before also, your cousin like you also,” Bibi went on in a soothing voice. “Last week she saw a setan and ran away in the night. Then she came and slept at night in my house.” Bibi looked accusingly at Husen. “Where were you? Play cards all night, going everywhere, leaving your wife alone. There, there, Kar. So all right. If you can already get up, come, we go to my house.”

“Wah! You don’t be afraid, Kar,” Husen was getting impatient with Bibi. “Setans don’t eat people. Where is the setan that eats people? No.”

“I saw it running down the lane,” Muri offered. “For forty days and forty nights I not sleep and so I can see him. If in Java, many, many setans” (a generic term for ghosts, not necessarily the Christian “satan”).

Husen remembered that Muri had left his djimat in their other room. “Okay, Muri, better you take away your stone. Better you take it back to your place.”

They went to look for it and Muri told Husen he had seen setans before on Dieng Mountain. To gain supernatural powers, he said, he had also visited the Bantan village of Bodwe, west of Djakarta, where the men wore only black shirts, black pants and black capes and carried suitcases made from pandan. One was called Kaneron. The Bodwe men never traveled by vehicle but always walked and no white man had ever dared visit their village.

When all the neighbors had gone home, Husen took his flashlight and went about the two small rooms, flashing its beam in all the corners and crannies, even crushing an ant crawling up a wall to be on the safe side. Then he sat on the bed by Karniti’s side, confused and so worried and apologetic, his eyes watered. “I thought you were good, Kar. That’s why I played cards. Oh, Kar, I’m so sorry. In all the world, I have only you to look after me and in all the world you have only me to look after you. Your mother and father are in the village.”

Karniti smiled. Now that Husen was back by her side, it seemed as if she had come to the end of her strength. Her fever was higher now and she felt drowsy and sinking into sleep. Husen rose and poured her a glass of steaming hot tea. Her voice heavy and drowsy, Karniti murmured, “Go back to your game. Go to bed, Husen. Why do you just sit there? I’m all right now. Go to sleep.”

But Husen was too confused and bewildered now to sleep. “I’ll just sit here, Kar. If any setans come, I have this,” and he brandished the heavy flashlight. “I remember how it was when I was sick that time in Bongkaren, Kar. With no one to help me, even to go to the toilet. I wanted to die, Kar.”

Karniti opened her blurred, feverish eyes and stared at her husband’s worried face. There was something she had wanted to tell him, she thought drowsily. What was it?

Husen wiped her wet, feverish forehead with his handkerchief. “Go to sleep now, Kar. Everything’s all right. I’ll be here beside you.”

“I went to the dukun today…”

“Just go to sleep now.”

“Husen. I have baby now in myself. Two months already,” she said calmly. He looked at his wife and she looked back at him. Her hair was wet with her fever and her eyes were sunken. Beyond this, she was as she always was. To Husen, she was unbearably touching lying there. His heart rushed out to her and he said, not knowing what else there was that could be said, “Alhamdullillah!* (“Allah be praised!”) I hope God gives us happy.”

“Yah,” she whispered. “I am also.”

“Kar, if this time I have a little success finding money in Djakarta, a little success, if not too bad; then we save everything and go back to the village.”

“Yah, maybe in the village…the air is good…” She was drifting off to sleep.

“In Tjirebon there’s cholera, Kar. I read it in the newspaper. I think better you stay here until the rains come and I will try to find money and if success, then maybe we go home to stay this time.”

“All right.”

“If Abu helps me, I want to know the new ways and the different things about planting. I want to try, Kar. And I want to build you a little warung by the road, where you can sell things like you want, maybe a little tea, coffee, cakes. Not big.

Just a little one at first and maybe little by little…”

Her voice was barely audible. “Yes, I hope it is success. Do what you like.”

Karniti slept. But Husen, in his bewilderment, remorse, confusion and happiness, talked on. “I will ask my father to give me a little land along the road, yah, better, because maybe next year the government will widen for the Tjirebon bypass. A little land from father’s rice field and I want to carry earth from the garden and sand from the river to make the ground higher. I will get Tarja and Djuned to help me. Yah, also better, maybe plant some banana, kersem, papaya and so on. I think maybe I can make the house for twenty thousand. Because we are poor, Kar, we must go slowly. Maybe long time complete. Yah, and buy red stone from my uncle and djati trees from Tjibanteng Garden. Three rooms, one for the warung, a little kitchen and one for us to sleep. Maybe five or six months more and I can find the money, Kar. Yah, we’ll go back to the village. You must eat good and have good air so the baby will be happy. And now I must be a good man, not drinking or going to everywhere so the baby will be a good boy. Because I am tired, Kar. Fifteen years in Djakarta, a long time already. I think better we go home now. Stay in the village. I want to try…” In the morning when she awoke, refreshed by a deep sleep and her fever gone, Karniti found Husen still sitting there, one hand on her arm, his head toppled to one side and the flashlight still clutched in his hand.

Forty Dollars And A Wedding Ring

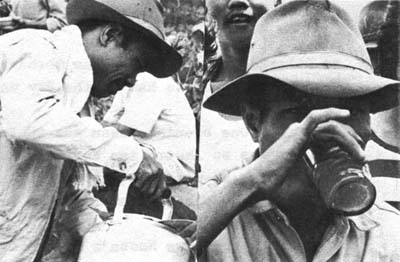

Twilight at the Hotel Indonesia. In the traffic of Welcome Circle, polished cars glistened in the setting sun. There was the pleasant, clear atmosphere of the Djakarta evening, a deep blue sky overhead and a fresh breeze. European guests moved along the lighted, open terraces of the hotel, looking expensive and luxurious. Some betjak drivers gathered around a food vendor’s stall; others sat in their betjaks, resting and waiting for passengers. A few were playing paper dominoes on the sidewalk and others squatted over a betjak cushion, gambling for money.

Twilight at the Hotel Indonesia. In the traffic of Welcome Circle, polished cars glistened in the setting sun. There was the pleasant, clear atmosphere of the Djakarta evening, a deep blue sky overhead and a fresh breeze. European guests moved along the lighted, open terraces of the hotel, looking expensive and luxurious. Some betjak drivers gathered around a food vendor’s stall; others sat in their betjaks, resting and waiting for passengers. A few were playing paper dominoes on the sidewalk and others squatted over a betjak cushion, gambling for money.

“Hello, Mister! Where are you going?”

A foreigner was approaching – a man of unusual height. His balding head was uncovered, he was dressed in black and smelled of alcohol. On his pallid, bony, corpse-like face stood out a damp, lank black moustache. Nodding politely in Husen’s direction, the man passed several other betjaks and noiselessly climbed in Husen’s. As Husen started pedaling, the man said softly, half turning in his seat, “Better your betjak.”

Husen grinned. “Do you like going around with me? Okay, let’s go. Where are you going, tuan?”

“That’s up to you,” said the man, half-turning and smiling faintly. Husen noticed he had yellowish, protuberant teeth and that, his hand, resting on the back of the betjak, had long, bony, nicotine-stained fingers.

“Maybe you want going to the bar, okay?”

“No, not to a bar.”

“What do you like, mister?” They were moving down Djalan Thamrin now and when they passed Sarinah department store, Husen turned the betjak into Kebon Sirih, a large thoroughfare leading to many bars, and restaurants. Under the heavy foliage, the street was dark and the man, stirring slightly, reached back and clasped Husen’s leg just above the knee in a tight grasp. “This…your leg is very strong.”

“Okay, mister, of course, because I am long time driver of betjak.” Husen was not unfamiliar with such approaches from foreign guests at the Hotel Indonesia and he quickly asked, “Do you like boy, tuan?”

“Yes.”

“Do you like with me?”

“Okay.”

“If you like with me, tuan, I am not like. Because I have wife.” Husen, who had been working very hard since Karniti had told him she was pregnant, did not want to lose the fare. He thought for a moment and considered looking for Rodon, another betjak driver, from the Hotel Indonesia stand who was unmarried and sometimes slept with the bantjis (male prostitutes; transvestites).

“I have friend, tuan, if you like boy,” Husen said after some time. His name is Rodon. He is very smart and tall. He is a betjak driver sometimes at the hotel.”

“Where is he?”

“Over there in Senen Market, tuan. Over there I can look for my friend. He is many times stop in Senen Market, in a small restaurant there.”

The passenger agreed but when they reached the crowded marketplace, with its thousands of electric bulbs gleaming like fireflies in the night, its glare of moving cars and the smells of food exuding from the stalls and restaurants, the man said again in his soft voice. “Okay, driver, stop here. I want to drink beer. Please go look for your friend. Hey, what’s your name?”

“Husen.”

“Okay, Husen, I’ll wait for you here.”

Husen searched through the bazaar for an hour but could not find Rodon; it was ten o’clock when he returned to the restaurant, and found the foreigner sitting with a youth with a pale, sorrowful, sickly face; he looked a mere boy. The two were speaking English and six empty beer bottles were on the table. Their glasses were still about a third full so Husen approached them and the foreigner offered him a glass of beer, saying, “Okay, Husen, this boy is also all right.”

Husen said to the youth in Indonesian, “Do you really want to go out with the gentleman? Are you sure?”

The Indonesian youth, who looked ill and frightened, asked Husen, also in the vernacular, “Where does he want to take me?”

Husen asked the man where they wanted to go.

“Surapati Park,” he said.

They returned to the betjak and the tall foreigner squeezed in beside the youth, first taking off his black coat and spreading it over his lap. Husen pedaled them toward the park without attempting conversation. But as they neared the park, the youth, who told the foreigner he was a student, and seemed small, sickly and feeble, suddenly turned back to Husen. “Oh, let’s find another place. I’m afraid here.” Husen answered him in Javanese also, “All right, better find another place. Maybe he wants to rent a room in Pedjampogang?”

The student spoke with the foreigner, who reached back to pinch Husen’s thigh with his bony fingers and said impatiently, “All right, whatever you say is okay with me.”

Husen turned the betjak toward Pedjampogang once more passing the Hotel Indonesia and having to dismount and push the betjak over the big bridge behind it. Neither the foreigner nor the student got out and it was all Husen could do to bring them up the long incline. Then he turned off broad, brightly lighted Djalan Thamrin onto a dirt road by a canal and passed Rodon’s house. There Rodon, a healthy, muscular driver with broad shoulders, was standing in front of his father’s tea stall. He grinned at Husen, stroking his moustache and was wearing a clean white shirt over his betjak shorts.

“Who is that?”

“That’s Rodon.”

“Oh, that one is better.” The foreigner gave a faint laugh. “That one is better.”

“It’s up to you, tuan.”

Husen asked Rodon in Javanese, “Well, Rodon, what do you think? Do you want to go with this white man? He’s looking for a boy.”

Rodon ignored the question, but when the foreigner got out, handing his coat to the student, and said, “Ah, this one is nice. I’m going inside. You wait here,” the betjak driver, without a word, led the man into a dark alleyway.

The foreigner emerged alone in half an hour and told Husen, “Let’s ride back to the hotel.” He did not speak to the student but told Husen to stop the betjak when they reached Djalan Thamrin, where he gave the student some rupiah and the youth vanished into the crowds.

The next afternoon as Husen sat in his betjak in the line in front of the hotel, a bellhop brought him a note from the man written in English. It asked him to bring Rodon to his room that afternoon. Husen pedaled to Rodon’s house where the other quickly dressed in a white shirt and long trousers and they returned to the hotel.

Rodon was inside less than twenty minutes and when he returned he brought with him a note and a package of Salem Cigarettes. The note said, “Last night I lost some money – $40 in American money and 20,000 Indonesian rupiahs. Help me to find this money or I shall notify the police.” Husen was worried. “Did you take the money, Rodon?” “No, no. I didn’t.” “Okay, Rodon, we’d better go find who stole the money. If you didn’t take it I think the tuan means me.” He felt himself getting angry. Husen had never been in trouble before and now, more than ever, he had reason to stay out of it. He and Rodon borrowed a betjak and returned to Senen Market where the foreigner had met the student the night before. It was around seven o’clock and the evening crowds were just beginning to gather. When Husen saw a youth who looked like he might be a student, he approached him and asked if he knew the boy who was with a tall foreigner in black the night before. With luck, the student knew his friends address in Kali Barutim, a nearby slum neighborhood, and gave it, thinking the foreigner again, wanted to see his friend.

“Do you know how much money he got last night?” Husen grinned, trying to hide his anxiety.

“No, except he has two pieces of green money with ‘twenty’ in the corner.”

With great relief, Husen went back to the betjak and told Rodon, “He has $40 so it must be he who took the money.”

A few minutes later the student himself entered the restaurant. Husen went up to him, trying to be calm.

“Hey, how are you?” he grinned. “You were with the tuan here last night, weren’t you?”

“Yah. You took us around in your betjak.”

“I think you got a lot of money last night.”

“No, only five hundred. You saw him give it to me.”

“Only five hundred,” Husen laughed, “Why he gave me fifty thousand roops with two shirts and two trousers. That tuan is really rich. I came here especially to meet you and bring a message from him. He needs you to come to the Hotel Indonesia.”

“Why?”

“Because he’s going to Tokyo tomorrow.”

The student narrowed his eyes and said in his sickly, nervous voice, “I don’t want to go.”

“I think you better,” Husen smiled. “I have come here especially to call you. I think the tuan was very nice to you and he wants to give you a souvenir.” At last the student agreed to go, but he cried out in protest as Husen and Rodon squeezed into the betjak on either side of him, getting a friend to pedal it back to the hotel. As they neared the hotel, the student looked with terror first at Husen, and then Rodon. He blinked and little drops stood out on his brow. He wiped his forehead with his sleeve and drew a deep breath.

“I am not student,” he cried in his sickly voice. “I only sell cigarettes in the street. Please, I am a poor man.” His eyes filled with tears, almost moving Husen to pity, and then the boy confessed that he had taken the money. Together they went up to the man’s room in the Hotel Indonesia. It was a large suite, expensive and luxurious, and Husen knew it must have cost almost twenty or thirty thousand rupiah a day.

The foreigner again wore black but now he had heavy-rimmed spectacles and the air of a stern businessman. After he heard Husen’s story, he asked, “Where’s the money now?”

“I sold the dollars for eight thousand rupiah,” the cigarette man cried.

“No, impossible! If you changed the dollars you could have got fifteen thousand. If you cannot give me back all my money, I’ll bring you to the police.”

The youth was terrified. He asked the foreigner to wait an hour and with Rodon and Husen went back to Senen market where he borrowed seven thousand rupiah more from a Chinese moneylender. As they returned again to the hotel the student said it might take him half a year to pay it back.

Some nights later the foreigner, again apparently coming from the bar, passed Husen’s betjak and laughed. “You should be a detective, Husen.” Husen grinned back but he thought to himself, “And if not find the student, what then? Maybe jail for three months.”

But after that Husen enjoyed some reputation among his fellow betjak drivers for shrewdness in dealing with the foreign tuans. Some weeks later, when a friend, Tardja, got into similar trouble, he came to Husen.

Tardja said a foreigner had come out of the hotel one night and asked for “a good girl.” He had taken him to Planet, the city’s center of prostitution just behind Senen Market. The next day a security man or plain-clothes detective from the hotel had approached Tardja and told him someone had stolen his passenger’s wedding ring the night before. Tardja told Husen he feared he might be arrested and beaten by the police. “Don’t be afraid, brother,” Husen told him. “Because there is a Javanese proverb: ‘An innocent man knows not fear.'”

Together he and Tardja went to Planet, searching among the girls, with their powdered and rouged faces, trying to find the one who had gone with Tardja’s passenger. It was early and the little alleyways of Planet, formed mostly by abandoned freight cars from nearby Senen Railway Station, were just filling up with youths looking for girls among the tables and small orchestras. There were many soldiers sitting around drinking beer. Husen had not been inside Planet before – he usually waited outside at a betjak stand if he brought passengers there – and he was relieved when Tardja finally cried out, “Look, ‘Sen. That’s the girl. The girl tuan had last night. Let us stop her.”

Husen did the talking. The girl, with a plump, cheerful village face, listened with an air of bored indifference.

“You were with a white man, who wore a batik shirt, last night, weren’t you?”

“Sure. What’s wrong?”

He decided to repeat his tactic. “Oh, nothing. The tuan just wants to meet you. He sent us here to ask you to come to him. He needs you right now in his hotel room.”

“Okay, let’s go.”

Husen said nothing about the wedding ring until they reached the hotel. The man was waiting in his room. He was an American of middle height, gray-haired and stout, with a paunchy stomach. Two heavy-lidded, black mustached security men were waiting with him.

“That’s not the girl I was with last night!” the American protested.

“Oh, honey, I sure was. You forget me already?”

“Oh, yeah. I guess she was. Hmmmm.”

A security man spoke, “Sister, where is the ring of this tuan?”

The girl made a face at Husen. “Is that why you brought me here, you?”

The security man went on. “You stole this man’s ring, eh, yah?”

The girl laughed a rich, warm laugh. It seemed to Husen that the American gentleman turned a shade paler.

“No. Pak. I didn’t steal nothing. I was given the ring by this tuan. He said he was in love with me. He said that he never wanted me to forget him. He was happy, happy.” Her eyes shone with amusement. “He wanted me to have the ring so as not to forget him. But it was only white, not gold. I figured, who wants a ring like that? So I sold it to my boyfriend for two hundred roops. He’s wearing it. Why? Is it valuable or something?”

“It was platinum,” the American muttered in a small voice.

“Where’s your friend now?”

“He hangs out at the Djakarta Fair.”

The girl, Husen, Tardja and the two security men, with two betjak men pedaling them, all proceeded down Djalan Thamrin to the fairgrounds at huge Merdeka square.

The boy friend was there, standing idly outside the casino. “Hey, what’s up?” he grinned, holding a kretek jauntily in his, teeth.

“C’mere, Tjas, give me that ring back.”

“Okay. Take it. What the hell kind of ring is it anyway. It is not even gold. What’s it got? Some kind of magic?”

On the way back to the hotel the security men were apologetic. “This is a foolish tuan to give his ring away and want it back again. But we have to worry about our jobs too.”

The American was delighted to have the ring recovered. He gave Tardja a six thousand rupiah tip, half of which the betjak man promptly passed on to the detectives, sharing the rest equally with Husen.

They were ready to leave but the American wanted to pour everyone a glass of whiskey to celebrate and he, the girl, her boyfriend, Tardja, the two security men and Husen all raised their glasses in a toast. “Forgive me, everybody,” the tuan said, pouring another round. “If I hadn’t got this ring back I couldn’t go home to my wife. I dunno. Maybe she’d even divorce me.” Everyone laughed and Husen, feeling the warmth of the whiskey and the one thousand five hundred rupiah tucked in his pocket, told the American, “Tuan, I believe if you don’t do bad things, God will take care of you. That’s what I tell my friend Tardja here. So. I think, just don’t suspect someone in the future. Who knows? Maybe that one doesn’t do anything wrong. I myself was once accused of stealing.” With that, they all drank another toast.

The Bantjis

“Hello, mister! Where are you going?”

Another night in front of the Hotel Indonesia. A chubby, smiling, bespectacled Japanese businessman settles into Husen’s betjak.

“You like round the town?” Husen asks cheerily. “Aruku kah. Sampo sampo? Maybe you going to Casino? Bar? Senen Market?”

“Oh, thank you. Just around. I want to see Djakarta.”

“How are you tonight, sir?” Husen took the betjak out in the circle and crossed to Deponegoro Street.

“Oh, you can speak English very well.”

“No, just a leetle. You like going for round. Casino? Night club?”

“Just around the hotel. Because it is late.”

Husen pointed to the dark frame of an unfinished skyscraper.

“This is Wisma Nusantara. Japanese construction.”

“Oh, Japanese construction. Ah, so.”

They turned into Deponegoro. It was a cool, pleasant evening and not much traffic in the streets. From out of the darkness under the heavy foliage of some tamarind trees a feminine voice called out invitingly, “Hello, mister! Where are you going?”

“Oh, stop, stop,” said Husen’s passenger. “I want to talk to that girl there. Very nice, the young girl.”

“No, tuan,” Husen told him . “That is not woman, that is queer.”

But the creature that emerged from the darkness now gave every appearance of being a beautiful young girl. She was tall and slender with wavy long black hair, heavily-mascaraed eyes and moved with mincing steps, her hips swaying back and forth like a heroine’s in a sandiwara drama.

“No, no, tuan, that is queer,” Husen hissed in the ear of the Japanese, recognizing under the disguise Yan, a farmer from Babadan village, not far from his own.

“No, no, no, no! Stop! Stop!” his passenger sputtered and Husen put on the brakes and pulled over to the curb. Yan came over to the betjak and stood, running his hand up and down the sleeve of the passenger’s jacket. “Hello, mister.”

“Hello, there, heh, heh, heh. Do you have a room?”

“Oh, yes. I have a room. Just behind the Kartika Plaza hotel in Badu Radja Street.”

“Oh, that’s too far,” the Japanese giggled nervously.

“No, it’s very near,” replied Yan in an emphatic voice, climbing into the betjak beside him in an elaborately grand manner. “C’mon, please, let’s go.”

Husen started to pedal. But when they passed under a streetlight down the street, the Japanese backed away from Yan a little and stared at him for a better look. “Are you a woman?” he asked.

“Yes,” Yan answered, caressing his cheek. “I am a woman.” The Japanese, encouraged, put his arm around Yan.

For a few moments they rode on in silence. Then Husen heard Yan mumble in protest, “No, no. Don’t do like that.” Another silence and only the sound of the Japanese’s labored breathing when suddenly he exclaimed, “Hey, you’re not a girl! You’re a man. Stop this betjak! Please get out!” His voice rose to a shrill cry. “Get out! Get out!”

In his own male voice Yan said gruffly, “Please give me money.”

“You must be a girl to get money from me,” the Japanese sputtered angrily. “Now, get out, get out.” He half turned to Husen, looking for help, but the betjak driver’s countenance was one of studied neutrality.

“Look, mister,” said Yan, getting tough, “you already brought me too far. And not pay. Maybe I lost a customer back there. Give me two hundred roops.”

With relief that the price was not higher, the Japanese pulled out his billfold and thrust the money into Yan’s outstretched hand. Once paid, Yan got out of the betjak and disappeared down the dark street once more.

“Take me back to the hotel!” cried the Japanese.

“Okay, right or not?” said Husen. “That is not girl. What I tell you?”

“Yes, yes. Just take me back to the hotel!”

When Husen related the event to some of the other betjak drivers back at the hotel they all laughed. One said that some of the bantjis wore foam rubber vaginas and turned the lights out so that sometimes foreigners never did know they were men and not girls. Tjasidi, a friend of Husen’s, said that he had heard that recently one of the bantjis had washed his foam rubber apparatus and left it on the roof of his house to dry. A cat had come along and carried it down into the street to every neighbor’s amusement. Just then Husen saw Yan crossing Djalan Thamrin past the hotel entrance and he pedaled off toward him, telling the other betjak men, “Ah, I go speak with the bantjis. I am very much like joking with queer.”

Yan was sitting with two other bantjis, Ringit and Moomoo, on a low cement wall in back of the hotel along Djalan Thamrin; they were screened off from view by a thick hedge which surrounded the hotel’s gardens and swimming pool.

“Hey, Yan!” Husen called as he pulled up beside them. “Now my Japanese tuan won’t come back outside for a week.”

He parked the betjak and walked over to sit beside them. In their heavy makeup and false eyelashes and wigs, all three youths looked alike. Unlike Yan, most of the bantjis were Javanese from the city of Djogjakarta, or Sundanese from around Djakarta. A few of them were educated students or even professional men with families who chose to become transvestites in the evening either for money or their own sexual preference. But most of them, like Yan, were village boys who farmed some of the year and had turned to this way of life to earn money without the hard physical labor of driving a betjak or working as a coolie. They were to be found in several places in the city at night, even the spacious, leafy residential streets of Kebajoran Baru; but the biggest concentration was around the Hotel Indonesia and it was widely said that most of their customers were foreigners, although this seemed highly doubtful. The governor of Djakarta, Lieutenant General Ali Sadikin, a tolerant Javanese, had arranged for the bantjis to have their own stand at the Djakarta Fair, and there they gave musical and dance performances. Like the kangkung welanda, they only came forth at night; one almost never saw a bantji in Djakarta before the sun went down.

“Now are you looking for money?” Husen asked them in his good-natured way. “Give me fifty roops and I’ll go and bring a foreign tuan for you.”

“I know you, Husen,” Yan said in his own male voice. “We give the fifty roops and when I ask where’s the foreigner you say, ‘Oh, he’s sleeping now.’ Husen chuckled. It was a trick he had played on them before.

“Not yet find money, Husen,” complained Moomoo.

“If I am looking for you these days, Husen, I not see,” complained Ringit, whose falsetto voice and padded red dress could not conceal the broad shoulders and muscular legs of a farm youth who had worked in the fields most of his life. “You are not stopping here for a long time. I always watch you. All the time you stay with the other betjaks in front of the hotel. You look very happy. Joking with friends.”

“Why are you sitting here, not standing under the bridge of Dukuhatas?” Husen asked. “It is late already, maybe eleven o’clock.”

“If I am seeing you, you look very happy,” Ringit went on, “I know about you, Husen. You are nice boy. You are sometimes many joking with your friends. You never look angry, but many joking.”