Trudy Rubin

- 1974

Fellowship Title:

- The Impact of the '73 Middle East War on Egyptian and Israeli Society

Fellowship Year:

- 1974

Conversations About Peace

These conversations took place in Cairo during the summer of 1974, but they remain just as relevant today as they were then. Mr. Said (a pseudonym) is a highly placed, well-respected official in the Egyptian foreign ministry. He is deeply sympathetic to the Palestinian cause, both personally and politically, but is remarkably objective in his overall assessment of the Middle East conflict. He is convinced that peace cannot emerge out of a simple “deal” between the combatants, but will require a new, dynamic process through which forces on each side will strive to appreciate each other’s differences and to establish useful channels of contact with each other. The key to this process, he believes, is the future relationship between the Israelis and the Palestinians. Mr. Said: “The first aim of Egyptian policy is to preserve our security and territory. Now look at the October war…. It was designed to end the holocaust philosophy, the mentality which believes that all the world is out to destroy every Jew. We made it clear that we were not

Talking to the Fellahin

Cairo — Although sixty percent of Egyptians live and work on the land, the thinking of the great mass of fellahin (peasants) seems a mystery to outsiders and educated Egyptian city dwellers as well. Both supporters of the left and the right in Egypt concede that it is the middle class, grown large and strong under Nasser, which controls the political levers in the country. The right pictures the fellahin as a passive, infinitely patient mass, which will accept any regime imposed on it as the will of Allah. The visible left, limited now in Egypt to a small but articulate group of journalists, students and intellectuals, pictures the peasantry — without too much conviction — as a potential seedbed of political unrest, especially as the fellahin watch living standards in the city rise while the lot of the peasant remains basically one of poverty. “Not even the government knows what the fellahin think,” an Egyptian friend told me. Another friend, an observer of his country’s peasantry, explained, “There are many different kinds of Egyptian

Salah Jaheen: An Egyptian political cartoonist looks at the conflict

CAIRO — When Salah Jaheen, Egypt’s leading political cartoonist, was visiting the United States in 1964, he was invited to the home of a Jewish family in a small town whose name he has forgotten. “The wife brought me a cartoon from an Egyptian magazine with a Jewish stereotype — a crooked nose. I said that this was a stupid cartoonist who doesn’t know anything. “For years our cartoonists made a terrible mistake by drawing horrible Israeli characters. There is a joke that when the Egyptian soldiers came back from the front they said1we weren’t fighting Jews because they didn’t have dark beards and horrible noses.” If one is looking for the image that a country has of itself and its enemies, political cartoons are a good place to start. All the more so in a nation like Egypt where the illiteracy rate approaches 70 per cent and a picture can truly be worth 1000 words. In Cairo, political cartoons begin with Salah Jaheen, who draws for Al Ahram, Egypt’s leading newspaper. Jaheen is a

The Jews of Egypt

Looking Backwards The Jewish cemetery in Alexandria lay silent as I walked down its middle, the quiet broken only by the occasional bark of several vicious-looking guard dogs chained to rocks along the path. The language on the gravestones changed from one to the next: Italian, Greek, English, German, French, Hebrew — mute testimony to the polyglot make-up of the once fabulous Jewish community of Alexandria. The wealth of the dead was reflected in their tombs. The Austrian Baron Menasche, scion of a family, which arrived in the last century and founded Jewish schools, a temple and a hospital while making a fortune in banking and trade, lay under a marble canopy supported by four huge pillars and inscribed with the crest of his house. Many elaborate family mausoleums stood apart from the ornate marble headstones. At the far end of the cemetery small markers bearing a simple Star of David carried the names of Jews of French, English and Spanish descent who died fighting in Palestine and North Africa during World Wars I

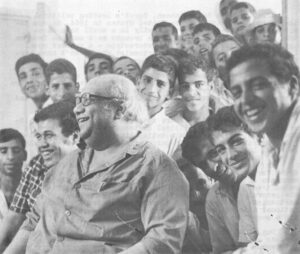

Students in Egypt After the October War

Cairo — Hisham met me in Lappis, the second most popular cafe and patisserie in Cairo, where the young, well-dressed middle class Egyptians — male and female — meet for ice cream and Turkish coffee and gateaus. Tall, with the broad-shouldered physique of a football player, brown hair curling over his forehead, his English excellent and eager, a son of the solid middle class, he was not exactly a typical Egyptian student (a little too well off, a little too worldly). But his emotions did not differ much from many others I met. He was studying journalism at Cairo University. He worked after class on the student newspaper which is put together in a bare, small room in the offices of the mass daily Al Akhbar, but has a circulation of 15,000, is sold at newsstands, and as a student run paper is less vulnerable to censorship than the big-time papers. Entrance to Cairo University Student cafe Cairo University Now that the atmosphere in Cairo is freer, he is rushing around to try to arrange