Looking Backwards

The Jewish cemetery in Alexandria lay silent as I walked down its middle, the quiet broken only by the occasional bark of several vicious-looking guard dogs chained to rocks along the path.

The language on the gravestones changed from one to the next: Italian, Greek, English, German, French, Hebrew — mute testimony to the polyglot make-up of the once fabulous Jewish community of Alexandria. The wealth of the dead was reflected in their tombs. The Austrian Baron Menasche, scion of a family, which arrived in the last century and founded Jewish schools, a temple and a hospital while making a fortune in banking and trade, lay under a marble canopy supported by four huge pillars and inscribed with the crest of his house. Many elaborate family mausoleums stood apart from the ornate marble headstones. At the far end of the cemetery small markers bearing a simple Star of David carried the names of Jews of French, English and Spanish descent who died fighting in Palestine and North Africa during World Wars I and II.

Despite a scarcity of visitors, the cemetery is well taken care of. It is protected from thieves by high walls and locked gates along with hired Moslem guards and watchdogs, (as are the neighboring Moslem and Christian cemeteries.) Its grass is trimmed and the pathways clear, but the marble of many stones is chipped or stained, and a few pieces, like the acanthus leaf clusters at the tops of the columns of a Menasche mausoleum have been lifted by thieves, despite the precautions. My guide from the Jewish community told me that it felt it would rather use its income to support those few Jews who were still living rather than to make expensive repairs on the graves.

We stopped at the small cemetery chapel on the way out. “We have no more Jews capable of washing the bodies (as required by custom),” my guide told me, “so we pay to have it done by Moslems now.”

Alexandria

I met Mr. T. in a small cafe and patisserie on one of the main shopping streets of Alexandria. The cafe has become a meeting place for those Jews who remain there. “About fifteen of us came here to sit and talk during the Kippour War,” Mr. T. recalled. “We were really nervous. We figured if they were going to arrest us we were making it easy for them. But no one paid any attention to us.”

Mr. T., whose parents had come from Greece, spoke Greek, Italian, English, French and Arabic. As we sipped chocolate ice cream sodas, we were joined by his sister, now living in Europe and making her annual visit, and another Jewish lady, vivacious and smartly dressed, who was about to leave for Europe to visit her son.

The conversation was largely in French, with bursts of English for my benefit. They talked of the past and the former rich life of the Jews of Alexandria and for the first time I began to understand the Levantine opulence, which characterized Durell’s novels about this city but was nowhere evident on its present-day surface.

“Why haven’t I left?” Mrs. L. asked rhetorically. “Where else could I have the life I have now? My husband is retired. We have a large apartment and servants and a car and the ocean. But we could not take this with us. How could we start over at our age somewhere else?

“Life here used to be marvelous. There were always parties and dances. In our building were fifteen apartments and you could be invited to a party there every night of the week. Yes. We socialized much in the Jewish community, but we were also invited to Italians and French and Greeks and Arabs, Christians and Moslems…. They were all our friends.

“Now there are no more parties. Most of the foreign communities are gone. We are the only ones left. After 1967 most of our Arab friends stopped inviting us.

“I haven’t seen my son for five years. I kept trying to get a visa but they always refused me and wouldn’t tell me why. I asked them whether they really thought I was Mata Hari. But things have loosened up since the October War. Now they have finally given me the visa and I am leaving next week.” (The problem is not to get permission to leave, but to get a reentry visa permitting one to return.)

Alexandria had by far the richest Jewish community in Egypt before the start of the Israeli-Arab wars. The community dates back to the Ptolemaic era, around the time of Christ. The treaty of Alexandria which sealed the Arab conquest of Egypt in 641 A.D. expressly stipulates that Jews be allowed to remain there.

In the 1930’s the city held 30-40,000 Jews. Today there are 200 left. They were a cosmopolitan group, engaged largely in trade, banking, and commerce, owning rich villas and apartments, traveling frequently to Europe, and sending their children to Jewish or European-run schools. Their first language was French, followed by Italian, but many also spoke some Greek and English, and the men at least usually spoke Arabia. They moved in the extensive foreign communities, which have nearly disappeared since the French-British-Israeli invasion of Suez in 1956, and the nationalization of most large businesses by 1961.

Their origins were diverse, some with families who had lived in Egypt or in other parts of North Africa for centuries. Many had come from Syria or Palestine to Egypt to escape the battles of World War I. There were Jews from Turkey, Rumania, Greece, Italy and France, and even some — though not many — with Eastern European origins, usually having passed through Palestine.

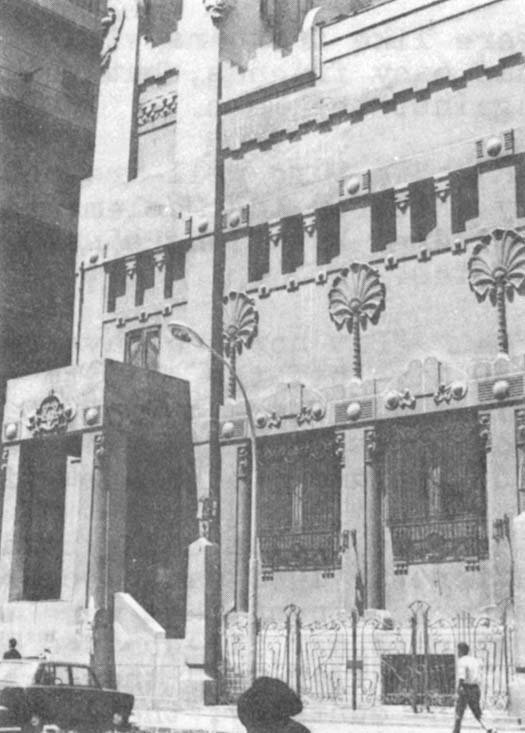

Besides eight major synagogues, the community in the 1940’s — headed by a Community Council owned a hospital, an old age home, several elementary schools, a lycee and ran several charitable organizations as well as a handful of periodicals, mostly in French.

Today, only two synagogues are still functioning, including the magnificent Temple Eliahou Hanabi with its stained glass windows and four rows of pink marble columns three stories high. There is no rabbi, although a layman performs his functions, and the community maintains the daily minimum of ten men required by religious law in order to conduct a service by paying them each the equivalent of $18 monthly. The temples are maintained with income from property still held by the community. But there are no weddings and bar mitzvahs any more, only funerals.

The Remnant

The Jews of Egypt — about 500 souls — are but a tiny remnant of a once wealthy and powerful community. Those who remain, nearly all elderly and most now retired, live on their memories and their photograph albums, pulling out endless piles of snapshots at the slightest indication of interest, to complement the photos on mantels and walls and bureau tops of children and siblings who have long since left for Europe or the United States or in fewer cases than from other North African countries for Israel.

So the second exodus of the Jews from Egypt is nearly over. But unlike the departure of Moses’ flock, the latter day flight was less a consequence of the persecution of the pharaohs (or the colonels as the case may be) than the tragedy of a successful and wealthy minority caught in the crossfire between their ethnic co-religionists in Israel and their compatible hosts of several centuries’ duration. While relations between Jews and Arabs in Egypt deteriorated after 1948 (and there has grown up a whole new generation which never experienced the era of peaceful co-existence), I was repeatedly assured by Egyptian Jews that there has never been persecution like that reported in Syria and Iraq and that religious rights have always been respected.

Many wealthy Egyptians spoke with regret about the loss of their Jewish friends. One Moslem matron confided to me that she visits her old. Jewish friends in Switzerland every year where their villa far outdoes their old home in Egypt. Another, a Copt, recalled attending “Suzie’s wedding”, Suzie being the present Mrs. Abba Eban, an Egyptian Jewess who married the former Israeli foreign minister when he was studying and lecturing in Egypt before emigrating from South Africa to Palestine.

Once, I was sitting in a Delta village asking some peasants if they could live side by side with Jews and they launched into a long description of “Mr. Weizmann” who had owned orange groves beside the village and had emigrated to Israel where his son was now a general and would certainly be welcome to come back if there were peace and he were still alive.

Every Egyptian Jew I met, without exception, assured me that the Jews had led a good life before 1948. One elderly Cairo Jew, still wealthy, whose family has lived in Egypt for centuries, told me, his eyes misting over, “We had everything then. The Jews owned the banks, the shops; they owned and managed all the big societies of credit — the bourse and the cotton exchange. The banks used to close on Rosh Hashonah and Yom Kippour (the Jewish New Year and Day of Atonement).”

As we sat in his comfortable downtown apartment, he reeled off the names of famous Jewish families: “Yusuf Cattaui Pasha, he was Minister of Finance in the ‘30’s and one son was a deputy and another a senator: Madame Cattaui was first lady-in-waiting to the queen: there was Chicorel and Chemla and Addis — they owned the big department stores — and Green, who owned many buildings and was a cereal merchant and Alfred Suares, who founded the National Bank of Egypt at the turn of the century and of course, the Mesnasche family in trade and banking….

“In Cairo we had 15 synagogues and a big Jewish school and a hospital. The Jewish doctors had many Arab cust9mers. They recognized that the Jews were clever. Before 1948 we were like brothers with the Arabs. The older generation still has many friends, but the new generation under Nasser has turned against the Jews.

“We were well-treated and had all our satisfactions here. My children had Moslem friends in the Lycee Francais. (His children have long since emigrated to Europe and the United States.)

“But now, we have nothing, nothing. Of 250 Jews in Cairo, 150 live off the charity of the Jewish community. They are all old. There aren’t 50 families, which still work for a living. Sometimes we can’t even get a minyan (ten men) in synagogue. Why, we used to have parties with 150 people….”

The exodus of Egyptian Jews did not start immediately after the 1948 war. According to members of the community, many prominent Jews were interned after 1948 and held in camps, but were not ill-treated and were finally released. I was told, “After 1948 there was no intensive official hard feelings. On the contrary, there were still very good business relations and Jews were respected and appreciated.”

In 1952, a wave of nationalist Xenophobia swept Cairo and many big shops and a hotel were burned down during a rampage known as the ‘Cairo fire’. The Jews, many of whom held foreign passports and were lumped by the nationalists with the other non-Egyptian owners of most of Egypt’s business and industry, were one of the targets of this rage. But the wave passed, and King Farouk reimbursed property owners for damages. However, in July 1952, the Free Officers Movement, including the then unknown Gamal Abdel Nasser, overthrew King Farouk. At this point many wealthy Jews began to leave.

During the next four years, “there was no open persecution, but you felt if you needed a special signature, people were reticent about giving it to you.” Young Jews holding non-Egyptian passports found it hard to get jobs, although Egyptian Jews did not feel so much animosity.

The invasion of Sinai in 1956 by Israeli, French, and British forces sparked a full exodus. Many Jews were temporarily interned and their property sequestered. All British and French citizens, which included many Jews, were ordered to leave. Among those Jews who remained, many were dismissed from all official positions and kicked out of all clubs. (They were later allowed to return to some jobs, at lower levels, and club memberships were eventually restored.)

“Feelings against Jews were high but were restrained,” one Cairo Jew recalled. “You could leave the country but you had to leave everything behind. But they never threw Jews out of the university, and we were not limited in movement within the country. They were reasonable, not like in Syria or Iraq.”

In 1961 the Nasser regime nationalized all large firms and foreign banks which included, of course, Jewish-owned firms, leading still more Jews to leave. In addition, many families whose children had been sent abroad to university and could not return began leaving to join their children.

By 1967 about 5,000 Jews were left in Egypt. The Six Day War spelled the virtual end of the community. During the war, 400 men between the ages of 18 and 50 were interned as a potential fifth column. About 150 were released after several weeks, mostly holders of foreign passports, but the remainder were held for three and one-half years. During the first few weeks they were treated badly, including beatings, but after that treatment was adequate, and visits allowed. Ironically, they were held in a camp for political internees, which included members of the fanatical Moslem Brotherhood, apparently leading to better understanding between the two groups, according to Cairo Jews. The internees were finally released upon agreement to leave the country immediately. Seventeen refused to emigrate, preferring prison, and were finally let go. (For some inexplicable reason, when recently questioned by a group of Jewish journalists about the internment incident, Egyptian Information Minister Kamal Abul Magd denied that it had ever happened, and asked one journalist to bring him specific details. Several other Egyptian officials spoke openly of the affair to me, some defending it as necessary for security reasons, others feeling it was a mistake.)

Those Jews who remain live quietly and inconspicuously. The community is elderly and increasingly depleted by funerals. There are still some lawyers, a doctor, a few teachers in private schools, skilled workers, some government workers (but only in unimportant posts) and of course, the retired. One Cairo Jew is part owner of one of the city’s newest and poshest restaurants along with a Moslem and a Christian. I met three Jewish youngsters studying at the university.

In both Cairo and Alexandria, the communities depend heavily on income from property, which has not been disturbed by the government. This goes for upkeep of synagogues and cemeteries, and stipends for the poor. In Alexandria, where the property is worth about $2,500,000, it also supports a home for the aged with a communal kitchen, and a small monthly grant to nearly every Jew according to need. Some former Jewish school buildings are used by the Egyptian government and they pay rent to the Jewish community.

Jews with whom I spoke concurred that the Egyptian govern — has respected their religious practices. The Jews still own all their synagogues, and there has been no desecration, with the exception of petty thievery inside closed-up synagogues after the 1967 war. The Jewish cemetery in Cairo is in bad shape, with many of its marble stones looted. “I don’t think it is anti-semitism,” one Jew told me. “Gangs come at night. The Christian cemeteries are robbed also but ours is easy because it is open and not well-protected and near the desert.” In Alexandria where the cemetery is well protected, thievery is a minor problem.

There is no shortage of religious articles in Egypt. In Cairo’s Adli St. Synagogue, the only one open in the city, there is a surfeit of prayer books and torah scrolls encased in beautiful silver and inlaid mother-of-pearl cases. There is a kosher butcher in Cairo and both the Alex and Cairo communities bake their own Matzoh (unleavened bread) for the Passover holidays. But the last rabbi left Cairo more than two years ago, and the brief Saturday service seems more an excuse for the participants to commune with each other and their past than a religious service.

Synagogue functions are protected by government police. During the Yom Kippour War last year services were held: Jews entered by the back door while the police protected the front. There were no incidents. There is a policeman in plain clothes on duty all the time inside the Cairo and Alex synagogues. He serves two functions: He reports to the government who — especially foreigners enters, and he handles any complaints of the worshippers.

For the Jews of Egypt, the thorns in their existence are loneliness, and political uncertainty, and, on occasion, petty bureaucratic harassment. This is most noticeable in the area of travel abroad. There are no restrictions for Jews on internal travel (unless they are holders of foreign passports in which case general restrictions on foreigners apply to them But before the October War it was almost impossible for Jews to return to Egypt once they left it. Since the October war restrictions have eased and several Jews have received permission to leave and return. But the process is a long one with constant security checks and unexplained delays and constant questioning about the whereabouts of émigré relatives.

While there has never been any ban on Jewish tourists visiting Egypt, since the October War there has been an influx of Jewish visitors and Jewish journalists, including the editor of the Zionist magazine, Hadassah.

But when I asked members of the Jewish community whether they thought some former Egyptian Jews might try to return now, all echoed the words of one old man: “Before 1948 we were living perfectly. But I don’t see any solution now for the Jewish community here. We are living out our lives and in a few years it will all be gone.”

Cairo, August, 1974.

Received in New York on September 17, 1974.

©1974 Trudy Rubin

Trudy Rubin is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Ms. Rubin, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.