Cairo — Hisham met me in Lappis, the second most popular cafe and patisserie in Cairo, where the young, well-dressed middle class Egyptians — male and female — meet for ice cream and Turkish coffee and gateaus. Tall, with the broad-shouldered physique of a football player, brown hair curling over his forehead, his English excellent and eager, a son of the solid middle class, he was not exactly a typical Egyptian student (a little too well off, a little too worldly). But his emotions did not differ much from many others I met.

He was studying journalism at Cairo University. He worked after class on the student newspaper which is put together in a bare, small room in the offices of the mass daily Al Akhbar, but has a circulation of 15,000, is sold at newsstands, and as a student run paper is less vulnerable to censorship than the big-time papers.

Now that the atmosphere in Cairo is freer, he is rushing around to try to arrange interviews with government ministers and get “scoops” for his newspaper. Our meeting is just prior to the arrival of Richard Nixon in Cairo and he asks me breathlessly, “Does President Nixon read his mail? I have written him a letter saying that I think he should talk to a group of students while he is here. If he gives political information to Al Ahram or Al Akhbar (the two major dailies) it will not be so unusual, but in our paper it would really make a sensation — you know, his being so concerned about the youth, the future leaders of Egypt!”

He is a bit of a radical and a bit of a pragmatist with a dash of romantic patriotism thrown in. “You know, my father (a writer) used to write radical books but then when I was born he needed money to send me to a good school and so on, so be started getting commercial. I once wrote an article attacking him in our newspaper saying what he wrote was shitty. He smiled and said ‘interesting, but without this money you wouldn’t be able to travel abroad or have an allowance.’ I said ‘that’s your problem, how to earn money but still make good books.’ I must believe these things. Maybe when I graduate I will find too that I must do things for money, but for these years I must speak out for my principles.”

We are joined by Hassan, a skinny, tall, frizzy-haired young man with Los Angeles mod clothes which turn out to be the fruit of a nine year sojourn in Hollywood, studying film and struggling (not too successfully) to crack the Hollywood filmmaking scene. He has just returned to Cairo and is searching out anyone who will listen to him verbalize the agonizing arguments for and against remaining in Cairo or fleeing back to the California coast. “The crowds,” he moans, “I can’t stand it. It’s gotten ten times worse since I left. No privacy anywhere. How did I ever grow up here? And the films, my God! Music, belly dancing, and belly laughs. You can’t get money here to make anything else.”

He moves on to another table of friends and Hisham mutters crossly, “The university here gave him money to go abroad and study. Now he must come back and revolutionize the cinema here. I would never leave Egypt. Even if I were in prison, I would prefer it if it were in Egypt.”

Hisham would like to visit Israel. Partly it is the journalist in him, anxious to see what it is REALLY like (“the first thing I would like to do is talk to Dayan and see what makes him tick”). Hat there’s something more…a newly liberated curiosity I sense among the young, which seems to have become kosher since October 1973. Now that we know the Israelis are human, the vibes seem to say, why not find out more about them? Or, better still, why not stop worrying about them altogether and get on with our business here.

There is this contradiction of rampant curiosity and nervous impatience about Hisham as he talks about peace with Israel. “When I was small they taught me in school that the Israelis wanted to expand from the Nile to the Euphrates. In the last few years the books have differentiated between Jews and Zionists…. Unless there is a fanatic government here suddenly, I can’t see any new war occurring in the next ten years. Everybody just wants peace, development, and to be just like Europe.

“We fought for the Palestinians enough,” he says emphatically. We just want our land back and for the Israelis to give back to the Palestinians some of theirs. Now people mostly accept the existence of Israel as a state. They couldn’t before the 6 October war.”

At times Hisham’s pragmatism becomes unhinged, uncertain. “Can any Israeli really tell me from where to where is his country? Every Israeli has a different idea, one just the old Israel, one to Iraq. I think the new generation in Israel — the black panther people (a group of poor oriental Jews), Rakah, (the Israeli communists) are the only people we can talk to.” At times he doubts whether real dialogue can happen for twenty years — “the next generation.” But in the next breath he talks about meeting Israelis and forming friendships.

“I was at Brighton Beach in England when I was 17, for the summer, and my roommate in the pension was an Israeli. I looked at him and he looked at me and we decided we could get along. He was dating a Swedish girl, and I was going with an Israeli girl whom I met in a cafe owned by Iraqi Arabs. We all hung around together the whole summer — never talked politics. When I was leaving he looked at me and said, ‘It was nice, but you know if I meet you on the battlefield I’ll have to kill you.’ I said ‘Yeah, I know, I’d kill you too.'”

But somehow this talk of killing seems like glamorous bravado. His life seems to have little room for var. He is too busy thinking of the articles he wants to write about the educational reforms the government is going to have to make now that there will be peace, and about the new cities along the canal, and maybe, if he is really lucky, he can be one of the first Egyptian journalists to go to Israel now that things have changed.

The mood of Egyptian university students has totally flip-flopped since the October war. In the seven grim years following the bitter defeat of the Six Days War, students had exploded several times, pouring into the streets under Nasser in 1968 and again under Sadat in 1972. These eruptions took place despite the lack of any real student movement and an almost total lack of student political activity (other than the government-sponsored variety) since the Revolution of 1952.

The 1968 demonstrations, coming on the heels of the June defeat, were not specifically directed against Nasser, but were, in the words of one former student who took part, “against the shattering of the ideals which he had taught”, ideals exploded by the government corruption and ineptitude exposed by the Six Days War.

In 1972, the protests were a result of student frustration at the “no-war, no-peace” stalemate which had existed since 1967. They were largely spontaneous and relatively non-ideological, although some communists and Moslem activists did take part. Like American students in the 1960’s, radicalized against the Vietnam War by the fact that they faced the draft, Egyptian students had a very personal source of discontent. After the 1967 defeat, the Egyptian government began drafting university graduates wholesale — and KEEPING them in full-time service indefinitely. I met one graduate of the Faculty of Commerce at Cairo University who was released in 1974 after seven years of service, three of them spent on the canal guarding the tiny pocket the Egyptians held on the Israeli-occupied east bank, and one of those three spent perched in a tree as a lookout.

The student draft was based on the logical premise that a better-educated military would offset the technological gap that many felt was responsible for the 1967 defeat. But while logical, it meant that by 1972, at least 30,000 former students had been in the military for up to five years and neither they, nor the later arrivals, faced any prospect of being released so long as the conflict was left unresolved. And, their younger brothers and friends at the university, knew the same fate was in store for them.

When Anwar Sadat began to retreat from his promise that 1971 would be the “year of decision”, the students felt they were being lied to. They wanted facts.

One former activist recalled, “We were portrayed in the Egyptian press as communists who wanted war immediately, but it was not so. We wanted to know what was the government’s program, what were they going to do. We wanted them to do something, anything, and to tell us the truth about it.”

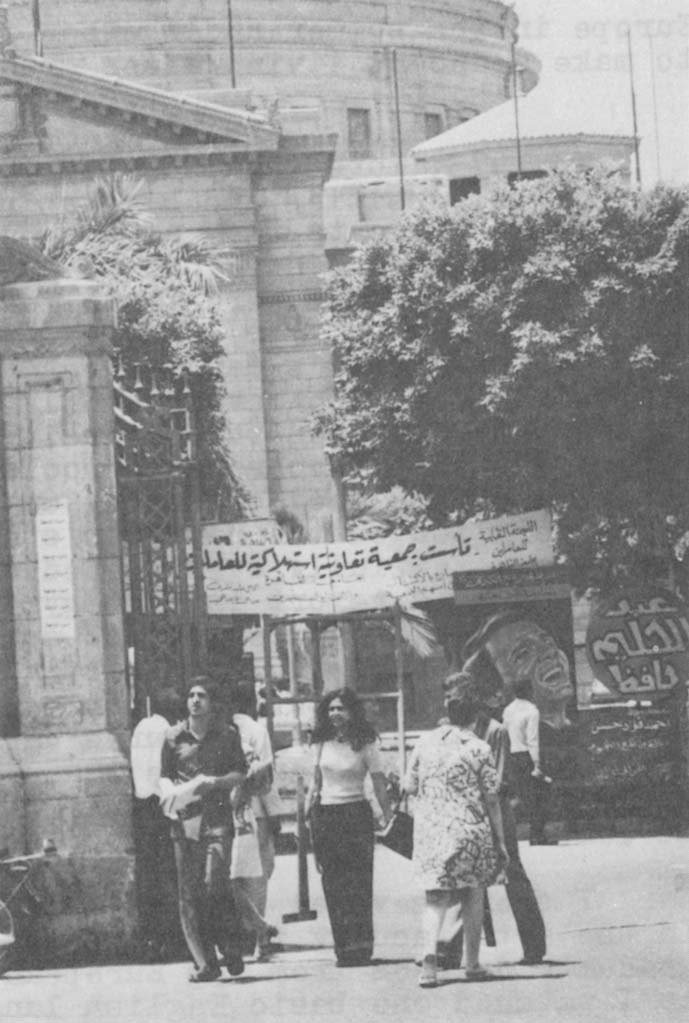

When the student demonstrators poured out of the Cairo University campus into Midan Tahrir, the city’s best-known square, Sadat cracked down and hundreds were arrested. Most were let out after two months.

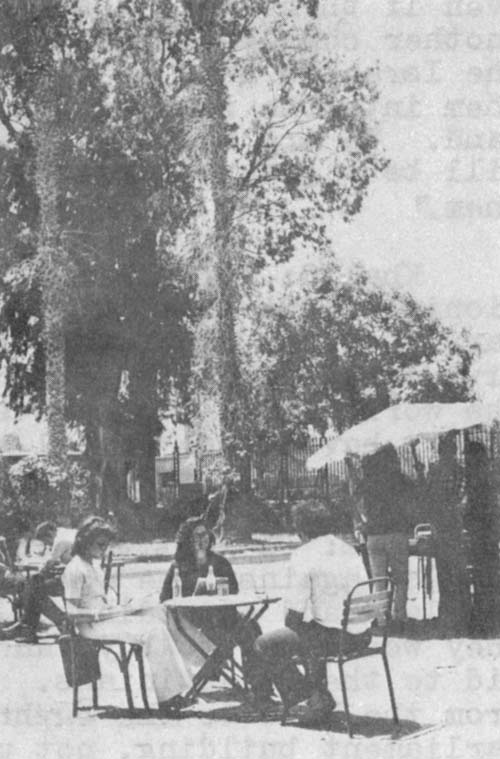

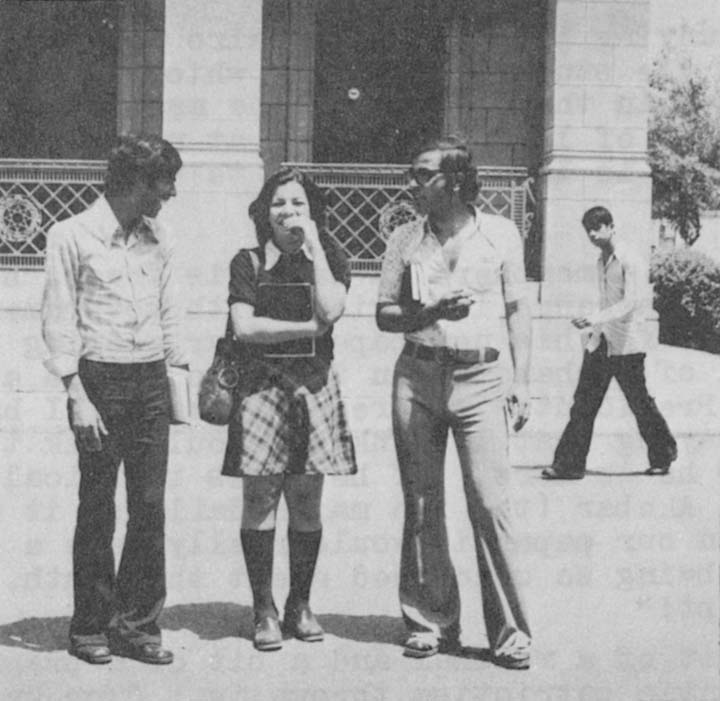

The 6 October War and subsequent ceasefire seem to have drained the discontent from the campuses. The left is silent. Religious activism is visible only in the persona of the many girl students wearing white kerchiefs and long sleeves and skirts. The students lounge on the campus of Cairo University, sitting on the grass under palm trees in front of the yellow brick buildings or at tables under beach umbrellas at the outdoor cafe. There is some talk of politics — mainly about the likelihood of American aid and Kissinger (with many jokes about why he picked such a homely wife) and Watergate and finally, Ford.

But the focus has shifted. The military seems only a one-year threat (though there is a small revival of talk of possible war). The new grumbling is personal and low-keyed — about overcrowded classrooms and the cost of books, about finding work in Europe in the summer and whether it is necessary to emigrate to make a decent living after graduation.

In 1973, more than 250,000 students were enrolled in Egypt’s universities and higher institutes of learning.

These students face an accumulation of all the problems Egyptian educators have had to overlook for the past seven years while all resources were funneled into the military effort.

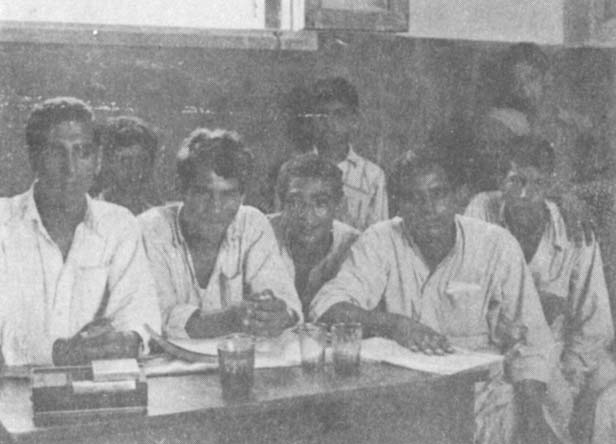

One of Nasser’s major reforms was to make higher education virtually free. Now every family, including peasants, aspires to send its children to university and see them settled into a government job. (Technical schools, which turn out much more needed — and in many cases better paid — skilled workers, are still very low on the Egyptian status pole.) As a result, universities are fearfully overcrowded, understaffed and under equipped. According to a report in the Egyptian newspaper Al Ahram, there is one professor for every 666 students and seven students work on every microscope. Students in the medical faculty of Cairo University protested this year — not for political reasons — but because their anatomy lectures were so crowded that many of the students could not even see the cadaver. (The university promised to install closed circuit televisions so the students could at least see the cutting second hand.)

I spent several days at Cairo University visiting classes. In the arts faculty the professors are highly qualified with graduate degrees from top European and American universities. But As I watched one basic English language section, the teacher could barely be heard, let alone answer questions, across a crowded sea of over 100 faces.

“The students are anxious to learn,” explained one faculty member with an American Ph.D., “but conditions are difficult. There are few books in the library, and usually only one copy. If they have a literature course with seven novels, they often can’t afford to buy them, especially since they have to be imported at high prices. And although I want to change the impersonal tradition of students’ memorizing professors’ lectures and spitting them back on exams, this is hard to do in conditions which discourage discussion and wide reading.”

When I asked some students what they planned to do when they graduated the answer was generally, “go into the army for a year” for the men, and then for both sexes, “well, I don’t know what job the government will give me.” In a bold move to prevent masses of unemployed college graduates, the Egyptian government some time ago decided to guarantee every graduate employment within a year from graduation. Since supply far exceeds demand, those students without professional specialties may wind up in ministries with little connection to their field — literature majors in the customs house, zoologists in the tourist ministry, etc. Most ministries are vastly overstocked with graduates, while fields with shortages, like teaching, somehow are undersupplied, perhaps because teaching has not yet acquired the prestige of a desk job.

Students also have to worry about their economic future. Graduates with a B.A. earn only 20 Egyptian pounds (EL) monthly after taxes (engineers and doctors make more), about $52, and thus must bank on marrying a spouse with a degree if family income is to cover the cost of an urban apartment and inflationary prices. For this reason, there is an enormous brain drain of teachers and engineers to other Arab countries, as well as badly needed scientists and professionals to Europe and North America.

Earlier this year, both President Sadat and Finance Minister Hegazy accused students of being less than patriotic. Mr. Hegazy scolded students for rushing abroad in the summer rather than staying home to help fight the cotton worm or rebuild the canal zone cities. (The lines in front of foreign embassies for visas in early summer often stretched around the block as students took advantage of the abolition of required exit visas to flock to Europe with a minimum of cash in hopes of finding summer jobs.)

Indications are, however, that the students do not lack patriotism so much as a clear idea of how they can be useful. Sitting in a small, sun-baked concrete bungalow adjacent to a one-story concrete elementary school serving three small villages in the Nile Delta to the northeast of Cairo, I talked to several student sons of local farmers who were working as summer volunteers to teach their elders in the village to read and write.

“These students are not going abroad to avoid working in the fields,” one dark-skinned young man, a student at a teachers’ training institute, told me angrily. “We have more than enough volunteers to teach at night. We have to turn people away. The problem is that the government has not organized enough projects for the young people to do.”

Whatever the problem, the government is taking steps to try to harness youth manpower. Extensive programs were set up this summer for youngsters to work clearing canal cities of rubble. And starting this year, university graduates, including women, who are not eligible for military service, will be required to do one year of public service, such as teaching in the provinces.

I wanted to talk about politics with students so Hisham brought some of his friends to the Cafe Riche. Riche is a hang out for students and literary types. It amounts physically to little more than three rows of small tables and uncomfortable wooden chairs set up in a small alleyway between two of the more fashionable downtown streets.

They were a good-looking group, all students at Ain Shams University, an ancient institution now situated on a new campus in the Cairo suburb of Heliopolis, almost American looking with a long central grassy campus surrounded on three sides by oblong unimaginative cinderblocks of classrooms, each building housing one faculty.

All had taken part in the student demonstrations in 1972 though none had been arrested. All were children of the urban middle class, their parents holding good jobs in the bureaucracy. We sat for hours, sipping mint tea and wiping away the perspiration, and discussing their attitudes towards politics and peace after the October 1973 war.

Hoda Hassan, the daughter of a judge, was studying to be an engineer. She pushed her long black hair back from an oval olive face with a smatter of freckles, as she tried to explain the students’ anguish before October 6: “After the 1967 war, with the military draft, students were tense and desperate about their future. There was no one ideology uniting them. There was the left, including some who were being paid by outside countries and there were the religious groups on the right. But the biggest group was the real Egyptians who wanted their country to have its freedom and not be occupied. Remember, the students had no idea that all this time Sadat was really planning war. I was really surprised to find this out later on. And you know, he didn’t want war but just to finish the whole thing so he could concentrate on development. The students believed there was no choice but war. I think they had a great influence on him. He started the war before the university term started.

Imam Mabrouk, also an engineering student whose widowed mother works for the Ministry of Education, sipped lemonade between sentences, her short curls brushing a clinging yellow sweater. “I was only a secondary student during the 1972 demonstrations but I was sympathetic to the soldiers standing in the sun for seven years.

“But now things have changed. The movement came last year because the students didn’t feel the rulers were sincere. After the October war we feel Sadat is a real nationalist who wants to serve his country. Even though we haven’t finished the war we have trust in our leader.”

Do they believe that peace with Israel is possible, I ask?

Khalid Yusuf, slim, serious, with spectacles, the son of a doctor, says slowly: “Peace between the Israelis and the Palestinians can take place…maybe…. Israel has the sympathy of the whole world because the whole world thinks the Arabs want to throw them into the sea. At the same time the Palestinians have rights and they have to go back. I believe that Egypt can live in peace with the Israelis but the problem is to create a compromise between the Palestinians and the Israelis who believe now that they own the Palestinians’ land.”

Ismat Essa, another engineering student, daughter of a scriptwriter, with short curly hair and a gap between her teeth: “Peace with the Israelis is expected but there are some things which must come first. The Arabs can’t live with a country which has done like Hitler with the Palestinians. It is difficult to forget 1948 and that the Palestinians live in tents. Moshe Dayan is supposed to be a genius but he is no more than a military man building everything on war.”

Imam: “You can’t believe Israel. Many times they said they would make peace and then they didn’t. They started three out of four wars.”

Hisham: “We don’t say Israel doesn’t exist. It must have a place, but…. They have a different mentality, European, not Middle Eastern….”

Ismat: “If you look to cities all over the world, Jewish communities are closed. They don’t open or give any link so any person can come inside. They are a kind of society which can’t easily mix with other societies.”

Hisham: “They are a strange people which makes it difficult to trust them. They are very intelligent and we admire them. They can still exist despite hatred all around the world.

“I don’t believe the Israelis could come here right away even if there were a settlement. We would have to have another complete generation, which existed after the war. The Israelis hate me because they think I want to throw them into the sea and I hate them because they took our land. We are enemies. After 40 or 50 years maybe there will be a generation which has love and friendship for them.”

Khalid: “Of all the Israelis, some are Jews, some Zionists. We lived at peace with the Jews before the war. But the Zionists. I think we could not at any instant live with them. They think they are the only people in the world and all others should be destroyed. We cannot always have these tribal wars which will continue if Zionism continues, because they want all the land.”

Imam:” I feel the Israelis are very intelligent. I’m not against the Jews but I am against Israel occupying the land and expanding. If we opened our country to them they would try to buy land and do the same thing they did to the Palestinians. They want to take the land from the Nile to the Euphrates; they wrote it on their parliament building, not us. I must not trust them. If they want to make me trust them let them destroy all the old books and the old ideology of Zionism and start a new thing. But no, they want to build on their own point of view.”

Do you approve of Sadat’s new relationship with the United States and his cooler relations with the Soviet Union, I asked?

Khalid: “I approve, because I think the United States has changed her policies. The United States made a wise decision because if they didn’t back justice they would lose the Arabs for good. This was also a decision for their economy. And also they were afraid to rely only on Israel because her image was not anymore that she was a strong country in the Middle East which could defend U.S. interests.”

Ismat: “Sadat was right. The Soviet Union was giving us weapons to use us in their campaigns, but we will never be communists. We have an Egyptian look for socialism. They wanted us to be Russians. They always wanted to limit our movement. They thought that there was no need to make war.”

Hisham: “The Russians have to change their look to the third world in the underdeveloped countries. What is the meaning of1third world’? It means the country is open to the whole world. We don’t want the Russians to look at us as useful for their ideology. We always pay for our weapons.

In the last war we paid cash. We are dealing as a customer and a seller, not more.

“We’ll never be Americans and never Russians. Now we are in the best situation. We want to make friends from the whole human community. We are putting our hands out for any friendship.”

Unlike their elders in the middle class, their admiration for Sadat is not accompanied by frequent criticism of his predecessor, Gamal Abdel Nasser. These are the real children of the Revolution, born after the 1952 coup by the free officers, and they still admire the man who created “Egyptian socialism.”

Ismat: “Nasser was a great man, a great leader in thoughts and ideology. Without Nasser we would never be sitting here. We can’t say he was a failure because anyone else in his position would have made greater mistakes.”

Khalid: “Nasser’s problem was that he liked all the world and wanted Arab unity. He died because of trying to solve the problems of Jordan and the Palestinians. If he died for unity it means he was very great.”

Hisham: “It is difficult to compare Nasser to Sadat, Nasser’s age with Sadat’s age. There is a great difference between Egypt in the 1950’s and 1960’s and now, and in the way that Arab countries relate to each other. Nasser’s great mistake was that he didn’t change with the times, with the change of great power relationships. The war of 1967 proved that wars between the great powers are over. The people who hate Nasser are capitalists. A real Egyptian who loves his country cannot dismiss him.”

Given the changes in Egypt and the world situation, I asked, are you willing to compromise with the Israelis for peace?

Hisbam: “This country would fight for thousands of years to defend its rights, but we hate war. I think in Geneva we will compromise. We will lose a little of our land.”

Imat: “We’re not going to fight for twenty kilo meters, but we are looking to eliminate the occupation. It is a matter of dignity, not kilometers.”

Khalid: “I think peace is possible. Why should we look for war? We will have a war only if we are occupied. If we are at peace there will be no war if they don’t come again.”

Received in New York on September 16, 1974.

©1974 Trudy Rubin

Trudy Rubin is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Ms. Rubin, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.