Cairo — Although sixty percent of Egyptians live and work on the land, the thinking of the great mass of fellahin (peasants) seems a mystery to outsiders and educated Egyptian city dwellers as well. Both supporters of the left and the right in Egypt concede that it is the middle class, grown large and strong under Nasser, which controls the political levers in the country. The right pictures the fellahin as a passive, infinitely patient mass, which will accept any regime imposed on it as the will of Allah. The visible left, limited now in Egypt to a small but articulate group of journalists, students and intellectuals, pictures the peasantry — without too much conviction — as a potential seedbed of political unrest, especially as the fellahin watch living standards in the city rise while the lot of the peasant remains basically one of poverty.

“Not even the government knows what the fellahin think,” an Egyptian friend told me. Another friend, an observer of his country’s peasantry, explained, “There are many different kinds of Egyptian peasant: those who live in the Delta of the Nile between Cairo and the Mediterranean the more conservative peasants of upper Egypt, those who live on the river, those who live by the canals, those who grow cotton and those who tend citrus: those who farm land given them by the Revolution and those who had land before and those who still have no land at all. Don’t make the mistake of taking them all to be the same.”

In the end I only met peasants from one province of the delta, El Sharkyia, stretching from Pt. Said at the northern end of the Suez Canal south to lush Ismailiya, midway on the canal and westward through the desert, stopping just short of the Damietta branch of the Nile. Government permits must be obtained by foreigners to visit anyplace other than tourist cities, and after much difficulty, I obtained one to travel to Oshkar, along with an Egyptian journalist friend as interpreter. Oshkar is a small village at the edge of the desert, about 75 km west of East Kantara on the Suez Canal.

The road to Oshkar runs along the sweet water canal, which was cut through the desert to supply the lovely city of Ismailia, base of the Suez Canal Authority, with fresh water after the opening of the canal. To the right of its banks, only a shallow strip of vegetation, fed by the canal’s waters, separates the canal from the desert.

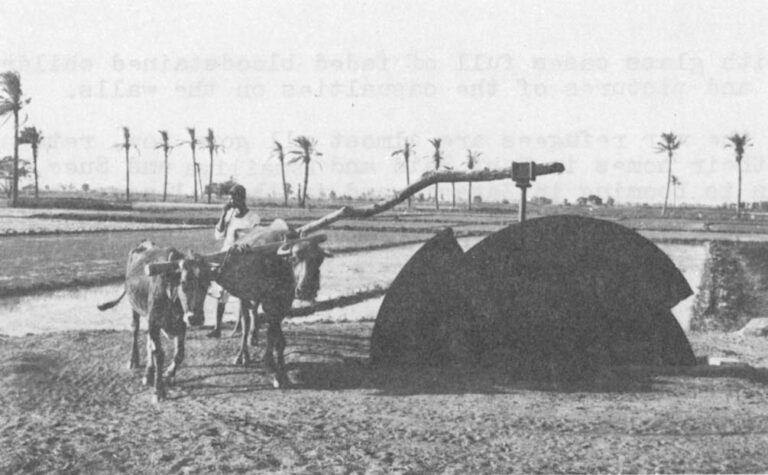

Near Cairo, the canal is lined with small industrial plants, and fishing dhows with long curving masts and sails anchor in its waters. Further along, stretches of wheat alternate with fields of sunflowers, or rows of giant cacti displaying prickly yellow fruit, which is sold in the markets of Cairo. Oxen, blindfolded with cloth strips turn wooden water wheels in the fields. Our battered taxi passes processions of women in black peasant gowns balancing baskets of mulhaya (Egyptian spinach*) on their heads: endless donkey carts loaded with fruit and watermelons: old ladies in black sitting motionless by the side of the road; an old man on a bicycle carrying a box of chickens on his back; tiny refreshment shacks, tin roofed with a butane gas burner burning tea, and warm dusty bottles of Egyptian cola on the shelves; and several open truckloads of young Egyptian soldiers returning from Ismailiya.

The war has left its imprint here. The province is near the Suez Canal and so became a haven for many of the more than 750,000 refugees who left the canal cities during and after the 1967 war when they were threatened by Israeli shelling from the occupied east bank of the canal. According to provincial officials, about 150,000 flooded into the provincial capital of Zagazig alone, and half a million into the province as a whole. They were housed with relatives, or in public housing, or in some cases in schools or mosques — sometimes for several years. Families were given grants of up to $30 per month, and attempts were made to find work for craftsmen or former government employees. This shift of resources slowed down the growth of construction and industry in the province.

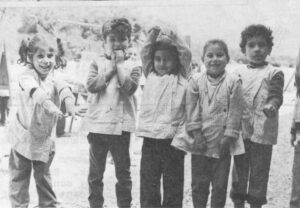

The war did not touch the villagers of El Sharkyia province so greatly in terms of casualties, since the population is so huge that each village seers to have lost relatively few men. But each village has many more men in service and has its wounded to bear witness. And being near the canal the province has had its bitter incidents. Most vividly remembered are the Israeli bombing of the basalt factory at Abu Zabal, killing about 70 workers, and more bitter — the bombing of the Bahr Bakr school in April 1970 killing 50 children. In Zagazig, a museum commpmorat6s this incident with glass cases full of faded bloodstained children’s garments and pictures of the casualties on the walls.

But the war refugees are almost all gone now, returned to rebuild their homes in Port Said and Ismailiya and Suez. Construction is booming in Zagazik and in the villages there is talk of new jobs along the canal if the plans announced to his people by President Sadat for now cities and industry in the canal zone are completed.

A Visit to the Omdah of Oshkar

The village of Oshkar sits at the edge of the province about 75 km from the canal. To reach it we drive along a rutted dirt road parallel to a narrow canal. The village is a small island surrounded on two sides by fruit orchards and on the other two by cotton fields. There are 2000 people here and about 60 per cent of the farmers own their own small patches of land. It is nearly dark as we walk through the sandy streets of the village. There is no electricity and we pick our way by the glow of kerosene lanterns shining out of the entryways of one-story mud brick huts, with figures of peasants and their animals dimly outlined inside the entry rooms.

We arrive at the house of the Omdah, the traditional village hood, a house distinguished from the others by its concrete facade, painted blue, its size, and its metal frame windows. We step into a dark cool hallway off of which is a sitting room with European style chairs and settees around the walls. A kerosene light hangs from the coiling, barely illuminating the severe portrait of the father of the current omdah, who also served as omdah until he was nearly 100 years old.

The omdah is away. We are greeted by his brother in galabyia and turban, a tall, sharp-faced fellow: and by the omdah’s wife, plump and uncomfortable in a western-style print dress. She is joined by his oldest living daughter, in her last year of high school, wearing slacks and a print blouse. We are seated and brought warm Egyptian cola (in old Coke bottles) and watermelon. Mrs. Omdah listens intently to the description of my work. She seems anxious to talk, to tell me of the progress of her children. Her face is round and serious: she speaks firmly and has read about the United States in newspapers and even seen two American films.

“My daughters are educated,” she announces through my interpreter. “My girl will be the first from this village to enter university. She wants to study medicine. All the young girls here arm learning in the primary school now, but few continue their education.” (I learn later, in one of those paradoxes, which characterize Egypt, that Mrs. Omdah’s oldest daughter died last year at age 17, just as she was about to enter university. She died because a childhood ailment, which had never been treated properly, was handled with traditional peasant methods rather than calling a doctor. Somehow, I feel that Mrs. Omdah must have fought for a doctor against the overwhelming refusal of the men in her family. )

“We have a club now for the youth,” she goes on. “There is a library and sports, but only for the boys.” When the Omdah’s brother serves my companions their cola before me, she notes loudly, “Unlike the American tradition, people here serve men first, but I do not agree.”

At one point, when we are speaking of education in the village, her brother-in-law interjects, “Why are we telling her the truth?” not realizing that my friend is still interpreting. She answers, “We must, because things are not so bad as people think they are.”

The Omdah’s brother, Mr. Mahmoud, is the head of the committee of the Arab Socialist Union (ASU) in the village. The ASU is the only civilian political organization in the country. Mr. Mahmoud’s role represents a key change in village structure, instituted by the government in recent years. Once the omdah was all-powerful. A major landlord in most cases, he alone maintained contact with the police and the central government. He inscribed the names of all the newborn (so he knew everyone), had the only telephone and — 40-50 years ago- the only radio in the village so that he maintained a monopoly on the means of communication.

But times have changed. In a move to modernize authority, the government has set up a local ASU office in every village, along with an elected ASU council, and appointed a village chief who is raid to check the schools, water, electricity and the streets. Since he is the contact with the central government people now consider him the leader, although the omdah still settles personal feuds.

In the village of Oshkar, the Omdah had maintained power through his brother’s post in the ASU. When his brother began to speak of the changes in the village since the revolution, I understood that this would be the official voice of the ASU.

“Life is more comfortable in the village since the Revolution,” Mr. Mahmoud told me. ”Now there is mechanization and the farmer can do his work in half a day. He has rights in the face of landlords. He has fertilizer and machinery and our village will have electricity next year (as part of a five year plan in cooperation with the Soviets to electrify all Egyptian villages with power from the Aswan high dam.)”

He is worried about the continued population increase — ”new housing is eating away land from the fields”. Madame Omdah says that -omen can come to her house and get birth control pills and that many are interested, but I learn later that few actually do come. The pills are given to her to distribute because the nearest doctor is 3 km away at the clinic in the next village. The Omdah’s brother is also worried about inflation in Egypt, but says that food costs are still low for the villagers although they have to nay more for things distributed centrally like cloth, soap or tea.

As for matters of war and peace, the Omdah’s brother feels the Americans can do a lot for Egypt “if they ant it. Let us see. We are a developing country. They can send us things to progress like you progressed. If they don’t want us in war we don’t want anything in peace.

“If Israel does not let go of our land, why not fight again? Many men have died from this village. Now, we do not say that Israel must die. They can live and we can live. There were Jews living here peacefully with Jewish neighbors — the son of one family is now a general in the Israeli army. If the Israelis have rights, the Palestinians also have rights.

“Zionist propaganda is the reason why Jews are fighting. It’s possible for Jews to live here again — why not? They lost men and we lost men.

“As for the Russians, they helped us in a critical time. First, the Americans forced us to go to the Russians for Aswan. Second, the most friendly one is the one who can help us reach peace.

My idea is that the world gave Israel its existence in 1948 and the UN frontier is the only legitimate frontier.

The Youth Council

About three miles down a dusty road from Oshkar is the mugamaa or community center, a cluster of one story dun colored buildings which are the elementary school, clinic and meeting place for Oshkar and its two neighboring villages of Sammakin and El-Ghazali. The mugamaa is also the headquarters for the local youth council whose officers are meeting when we arrive.

They are a handsome group, mostly the sons of peasants, all in secondary school or university, many the first in their families to be educated.

Hassan, the leader, with smooth golden brown skin and a long blue galabyia, is a graduate of a teacher training institute who works at the primary school here, the son of a fellah from Sammakin village, with a younger brother at the university branch in Zagazig (several universities have recently been established in the Delta in an effort to keep young people from flooding to and remaining in Cairo and Alexandria.)

His assistant Adel, tall and slender and a student in the commerce faculty at the delta city of Mansoura, wants very much to return to his village if he can only find a job there, the classic problem for educated village youths who want to stay near home. But Adel — the son of the owner of a small grocery store in Sammakin — has three job possibilities: as an accountant for the agricultural co-op, secretary to the village ASU council, or teaching it the high school of commerce in Farkouz, a large town 5 km away.

These young men do not appear rebellious or critical of the government: they speak enthusiastically of change in the village and even defend the government against charges of neglecting the countryside. (We are meeting alone with no officials present: my interpreter grew up in the next village and the boys all know and respect him.) The center, they tell me, was built in 1969 with clinic, primary and intermediate school and a nursery. Now there is a fulltime doctor and a family planning clinic. And there is talk now of starting a girls’ club for the first time.

More peasants than ever before are willing to spare their children from the fields because of mechanization, a hopeful sign since despite all the now schools, the Egyptian literacy rate remains at about 30 per cent, the same level as when the Revolution began in 1952. The government has now limited class size to 40, so the school has double sessions. Most of the teachers are local boys and there is no shortage.

The villages have changed too, I am told. Sammakin got electricity a year ago, and the other two are scheduled soon. There are now some television sets. A juice factory was built here and there are more tractors than before. Bilharzia, the parasitic disease, which once afflicted 80 per cent of the peasantry, has receded sharply since the government, provided fresh water pipes into the villages.

When asked if progress for the village was too blow, Hassan quickly defended the government: “If the city is favored over the village it is because the central government must work on industrialization, and this always takes place near the cities. Adel adds: “So many people leave the village for the city and this causes problems. The government should provide jobs so people can stay in the countryside. If the government brings electricity than the young men can have the benefits of the city and they will be happy to stay.”

The young men have begun their own projects at the center. They have started adult literacy courses in the evenings. They had these announced from the local mosques on Fridays and now they have more students than they can handle, although the few women who came at first have dropped out. They have sent student volunteers to work on clearing rubble from war-damaged cities on the canal.

In addition, they help their students put out two “magazines”: small essays on paper cut into shapes and fitted into slots in large cardboard rectangles which are then put into glass frames and exhibited on the clubhouse wall. All of the students are required to road the “magazines.” One of them has small essays and poems on themes like “being religious” or “taking care of one’s health.” The other is called “Wisdom of Men” And has interviewed giving the philosophy of local citizens, like an engineer from the village who is the son of a poor fellah.

They say they would like the United States to help with more mechanization and industrialization and electricity. As for peace, Hassan says his idea of peace is a just settlement for the Palestinians.” Why is this so important, I ask, when Egyptians have their own problems? “Because of Arab rights as a whole and because of humanitarian reasons.” And what are “just rights”? “A secular democratic state in Palestine.” Where should Israel go? “Back to where they were 25 years ago.”

The Co-operative

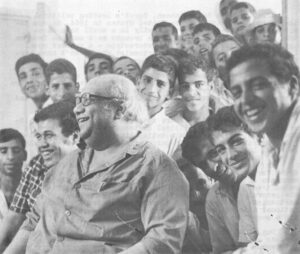

We are driving down the road when my friend the journalist suggests we stop at a low brick building on the road surrounded by several sheds. This is the local headquarters for the government cooperative, servicing the farmers in the area. Since the early 1960’s, the Egyptian government has been attempting to introduce a system of cooperatives into Egyptian agriculture by which many small peasant holdings are consolidated for production purposes into larger units which apply a uniform crop rotation thus enabling more efficient planting and use of farm, machinery, fertilizer and government technical assistance.

Gathered inside the shed are about twenty fellahin, modest peasants who received from three to five feddans (a feddan equals slightly more than one acre) under Nasser’s land reforms and may by now have already divided those meager holdings into smaller parcels for their sons. However, some of their sons, younger men who sit in peasant gowns beside their fathers, are no longer tilling the soil. They are students home on vacation, indistinguishable from their brothers beside them who have remained on the land.

One elderly man with a thin grey stubble eagerly introduced me to his son, a handsome youth in slacks and open shirt who spoke halting English and was a student in an agricultural high school. “I want him to go to the U.S. to study and to stay there,” the father lamented, “but he wants to comp back to the country and work at any job.

| The agricultural student and his father |

“My oldest son is an engineer at a military airport,” he tells us proudly. And his two eldest daughters completed middle school. “So all your children are educated?” I ask naively. Reluctantly he admits that his seven younger sons and three youngest daughters are at home working on the land. The other older men nod. It seems to be the pattern for one or two sons to go on to high school or even university while the rest remain on the land, perhaps attending primary and middle schools nearby when their father can spare them from the fields.

The men are eager to tell me what they want from the Americans: agricultural equipment, construction of new factories, and scholarships for their sons to study in the States. But when I ask whether they feel peace is near they are far more adamant than Cairenes in insisting “we are sue the war is not over.”

With my journalist friend translating rapidly, each one shouts louder than the next, trying to get his opinion heard, with more men crowding in the door as word spreads of our arrival. These men are less reluctant than city dwellers to risk offending their American guest.

“Is there any hope for peace?” I ask, and if so, “by what means?

“If America guarantees that the Palestinian refugees go back to their land.”

“In fact, we don’t accent the Israelis in the Middle East.

“What we wish for is that there was no Israel and only Palestine.”

“If we don’t get our land back we will go to war again.” Loud cheers. A fellah listening from outside the open window boosts himself over the sill and shouts, “We will fight thon to the last man.”

I am reminded of a conversation I had with an Egyptian journalist in Cairo, who told me that there was still much sentiment among the peasantry for war, which went unnoticed by the western press. He added that he felt President Sadat would have to undertake a massive educational campaign to convince the less educated part of the population that Israel should be accepted in the Middle East if she gave up conquered Arab land and settled with the Palestinians. This same man also remarked that the peasantry was politically sophisticated and knew what was going on — partly because of transistor radios, and partly because their children could now read.

Certainly these men were more militant than middle class Egyptians I met in Cairo. They admired Sadat immensely. But it was clear that Nasser was their greatest hero, despite criticism of him appearing at that time in the Cairo press. When I mentioned this, one wizened old man said with feeling, “Nasser gave us land. Before that we were ‘the penniless.’” Another grandfather added, “Before Nasser I worked on the land of a wealthy man. Last year his son came to ask if I or my sons would hire out to help with his crop. I told him we needed help on our land and he could hire out to us if he wished.”

How deep the resistance to Israel ran was hard to tell — the young students seemed more adamant than their parents. Anyway, the political realities of Egypt seem to provide the peasantry with scant political power. Their voice seems unheard, and in fact unexercised except in moments of exceptional emotional intensity such as the demonstrations after Nasser’s post Six-Day war resignation speech. It is hard to estimate what rural unhappiness with a peace settlement would mean or whether a plan could be sold to the fellahin if packaged properly.

There seemed to be less hostility here to the Russians than in the city, perhaps because few people here had actually come in contact with Soviets, unlike many Cairnes, and such contact seems to increase dislike of the Soviets in Egypt.

The fresh-faced agricultural student stood up and said almost defiantly: “We love the Russians. It is only because of them that we could fight. They are the major power.”

Another student chimed in: “We can’t deny what the Russians did.”

Another farmer said, “We don’t have any reason to prefer one to the other but the Soviets helped us more.”

And a philosophy student from Zagazig University said, “We prefer the one who was the most peaceful towards us.”

No blanket endorsement of the United States here!

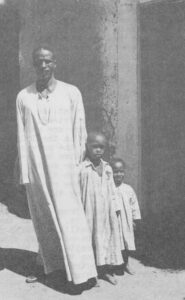

The black peasant and Nasser

I got a sense of the relative feelings of the fellahin for Nasser and Sadat from Said, an illiterate peasant employed by my journalist friend to tend the orchards on his property at the edge of the village. Said is tall and black, one of the few black men to be seen in the area, perhaps a descendant of African nomads. He lives in a small mud brick house, typical of the village, with a central courtyard shared by his wife, their four children, a. donkey, several chickens, and a large round oven to bake bread in. On the roof are pigeon coops and bales of hay.

I got a sense of the relative feelings of the fellahin for Nasser and Sadat from Said, an illiterate peasant employed by my journalist friend to tend the orchards on his property at the edge of the village. Said is tall and black, one of the few black men to be seen in the area, perhaps a descendant of African nomads. He lives in a small mud brick house, typical of the village, with a central courtyard shared by his wife, their four children, a. donkey, several chickens, and a large round oven to bake bread in. On the roof are pigeon coops and bales of hay.

Off of the courtyard is a small kitchen area with a butane stove, a tiny bathroom area with stand-up hole, and the family bedroom. There is a water pump in the courtyard. But unlike most peasant homes, there is a living room separated completely from the family/livestock quarters. This amenity is due perhaps to the urging and generous salary of my journalist friend’s late father, whose portrait adorns the living room.

Said worked in Israel until 1956. He used to cross the border with his Egyptian identity papers, as did many other Egyptian peasants, to pick fruit in Israeli citrus groves. “Why should I mind?” he asked me. “I used to work for Jews in Egypt.” Once he had a violent argument with his Jewish boss: he was thrown into jail for a month and then went back to work. But the open border closed after the Suez conflict. Today. Said worries about more elevated things. He fears that his son, who wants to be an engineer, won’t get high enough grades to enter the university. He wants to hire him a tutor, but the boy refuses.

One day we were all traveling in a service taxi, Said, my journalist friend, and myself, when the conversation turned to the relative merits of Sadat vis à vis Nasser. The taxi driver, who owned his rickety vehicle, staunchly preferred Sadat. “Nasser ruined the economy. He made the country bankrupt with the war in Yemen. Sadat will bring foreign money here to build factories. More tourists will come.”

Said sat back thoughtfully, obviously disagreeing. Then the fellah delivered his thoughts: “There was a time for Nasser,” he said. “He made our independence, he brought land to the peasants, he organized the country. Now is the time for one like Sadat to make relations with all countries. But he could not have reached this time without Nasser.”

January 8, 1975

Received in New York on January 15, 1975

©1975 Trudy Rubin

Trudy Rubin is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Ms. Rubin, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.