Near Greenup, Ky., where the Appalachian foothills meet the broad Ohio River bottomland, the subject was heritage, but the country under discussion at the moment was Greece.

“Now you take Greece for example. Sure, the Greeks have their world of science and knowledge. But the Greeks have another world, too. It’s a world of imagination, superstition, folklore, tradition. Well, we’ve got the same thing here in Appalachia.”

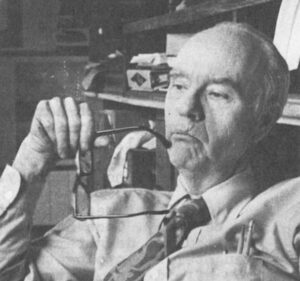

Jesse Stuart, a man not known for theories and philosophy, leaned back in his chair and reflected on what he had just said.

Jesse Stuart, a man not known for theories and philosophy, leaned back in his chair and reflected on what he had just said.

“The real world and the world of imagination,” mused the Eastern Kentucky poet, novelist, storyteller and teacher. “We live in two worlds here in Appalachia, just like they do in Greece,” he said chomping his battered cigar. “I guess the Greeks and the Appalachians are a whole lot alike. That’d be a good book for someone. It’s not my book, but it’s a book.”

Although he has become a symbol of Appalachia to many who have read his works, the 67-year-old writer is not one to generalize or philosophize about his native Appalachia. Instead, he explains his mountains through the characters and themes of his stories and poems. He speaks of Appalachia not in terms of a scholar but in the subtle tones of a writer of fiction and verse.

A native of Greenup County, Ky., Stuart has lived in W-Hollow almost since the day he was born.

Today, he lives in a comfortable house on a 1,000-acre farm. Ask him what he thinks about the culture that nurtured him and he’ll explain it in Appalachian scenarios, many of which have appeared in his writings.

Stuart is part of a vanishing breed. He’s a man who lives an Appalachian life, who’s proud to be an Appalachian, but feels no need to explain the Appalachian mystique.

While some scholars, theoreticians and writers work feverishly to define mountain culture and bring about an awakening of cultural awareness, Stuart is content to talk about his heritage in very human terms.

“It’s the character of the people that makes Appalachia different,” he says. “Appalachian people have character and they are characters. They’re originals. It was easy for me to find characters for my stories. If I couldn’t find characters within a mile of my house, I could find them IN my house. My parents were characters. All my relatives were characters.”

He recalls some of their names and chuckles: Henry Wheeler, Sweeter Barney, Uglybird Sinnet, Forrest King, Op Alexander.

“They were the older men of that day and time. They were the greatest characters I’ve known. Most of them couldn’t read. Most of them were dead before 1950,” the writer says.

Real people in a land as real as trees and rocks. That’s the Appalachia Jesse Stuart holds in esteem. That’s the Appalachia he has preserved in his novels and stories.

Like Appalachia itself, Stuart is difficult to classify. Ruel E. Foster, chairman of the English Department at West Virginia University and author of a critical work (Twayne Series) on Stuart, says that although Stuart is “ignored by serious literary critics, because his work lies outside the currently fashionable modes…millions of readers have read enthusiastically his poetry, fiction and autography.”

Out of step. Ignored. The writer and his heritage are one.

But it’s changing, for Stuart and Appalachia. The mountains are a new fad, or so it seems, and Stuart is one who thinks the glory of Appalachia is about to unfold.

“There’ll always be an Appalachia. The ‘other world’ hasn’t died in Greece. It’s been there for thousands of years. And, I think it will persist in Appalachia.

Although “the originals,” as Stuart calls them, are gone, individualism remains to some degree, almost as if it were an inherited trait. Stuart reveres it.

“My dad always told us never to live where we could see the smoke from another man’s chimney. He told us we should never live so close to another’s house that the chickens would mingle in the woods.”

All his life, he says, he’s been amazed and amused by others who are curious about Appalachia and its people.

“I spoke one time at Breadloaf Writers School. While I was speaking, I noticed Robert Frost taking notes. Afterward, he came up to me and told me I had spoken some of the strongest and best language held ever heard. Frost asked me where I learned to talk like that. I told him we all talked like that in Appalachia.”

But, Stuart says, he has seen some of the strongest words disappear from Appalachia, especially those most closely related to Elizabethan English. He mourns the loss. “Most of the time, they were stronger, better words than we’re using today.”

Even now, he hears occasional expressions, which delight him. “The boy that cuts our grass is a native. He told me the other day that something was as slow as pond water. I like that. It makes the point, doesn’t it?”

For every time Stuart has seen the culture praised, he says he’s seen it damned or misinterpreted. More than a decade ago, when Appalachia was being portrayed at every turn as the last bastion of poverty and ignorance in America, Stuart was on a U.S. State Department tour of the world.

“We were over in West Pakistan and they wanted to make up a collection to send to the people of Appalachia. And they’re the poorest people in the world, I guess. But, they thought we were worse off in Appalachia.”

Now, with the revival of the coal industry, and increased curiosity about Appalachia, he thinks the image is slowly changing. “The Bible says that the last shall be first and the first last. It looks to me like that’s what is happening in Appalachia.”

But the stigma of “poor Appalachia” remains, he says. “You go from here to Pikeville (Kentucky) and you’ll see lots of nice homes. Pikeville is a boomtown, what with coal. But you’ll find an occasional tarpaper shack with tin cans in the yard. Well, that’s the place they (the news media) still photograph and take out of here.”

Beyond his belief that Appalachian culture will survive in some form, Stuart doesn’t know what the future holds for the people and the mountains.

He sees around him programs designed to make mountain people aware of their heritage. The irony, he says, is that the originals never thought of themselves as Appalachians. They never read about Appalachian culture or heritage. They weren’t aware of who they were. They simply lived their lives the best they knew how.

Today, school children and their parents as well read of their heritage. They attend fairs and festivals designed to promote Appalachian heritage. They’re told they should be proud of who they are.

How will this Appalachian awareness change the people and the culture?

Stuart ponders the question a moment and bites again on the tip of his unlit cigar.

“I don’t know. Maybe it will make the people stronger. But they’re learning their heritage from books, not from tradition. I don’t know. I just don’t know.”

True to the Appalachian form, Jesse Stuart, the mountain man, refuses to speculate on the uncertainties of the future.

Received in New York on May 5, 1975.

©1975 Dave Peyton

Dave Peyton is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Huntington Advertiser (West Virginia). This article may be published with credit to Mr. Peyton, The Huntington Advertiser, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.