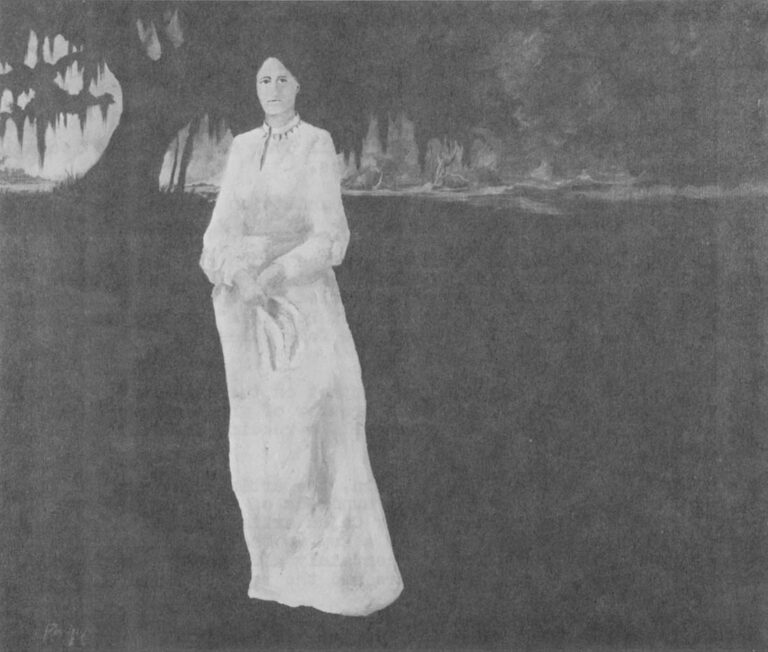

George Rodrigue paints pictures of ghosts.

They hover in his dark Louisiana landscapes, suspended between heaven and earth, not really belonging to this life or the life hereafter.

They stand like cutouts, pasted on a backdrop of shadow and mystery.

They are Rodrigue’s Cajuns, ripped from the past and placed in the present. They are people without homes, without motion and without futures.

“All my people just got dressed up for a Saturday afternoon,” Rodrigue says. “But when they finished dressing, they realized there was nothing to do. So, they sit in trees, they ride mules, they eat ice cream under live oaks. Or, they just sit and stare.”

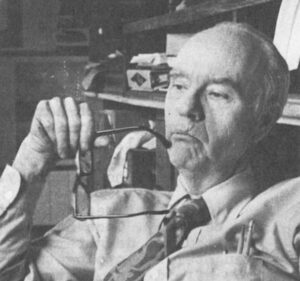

Rodrigue is one of the people he paints. But he’s much more. He may be the first Cajun to develop a new style of painting to portray his people. He’s certainly one of the first Cajuns to recognize the potential of the Cajun folk culture.

But most important, perhaps, he may be the one clear signal that the Cajun culture is falling apart and coming to an end. In another decade or two, all that may be left are the images Rodrigue and others like him choose to remember.

Rodrigue is special because history indicates no Cajun artist or writer has made a name for himself outside his own cultures In fact, the Cajun artists today can be counted on the fingers of one hand. It could be said that the Cajun folk culture has never been strong on art.

The history of Louisiana, from the time it was a French colony, is amazingly void of artists and art. In his book “Louisiana: A Narrative History,” Edwin Adams Davis notes that both during the French and Spanish periods, leading up to the Louisiana Purchase, little art was produced in the colony. French and Spanish immigrants brought art with them to the new world but the art was not New World-inspired. In the American period, following the Louisiana Purchase, New Orleans became an art center, Davis says, particularly for portrait artists. But these painters catered to the rich plantation owners. Their styles were European and most were “production oriented.”

During the 19th Century, Davis says, “no native born artists were produced who made reputations outside the state.”

New Orleans was the home of several artists when the 20th Century dawned, but most were landscape painters and there were no Cajun painters. The Atchafalaya Basin separates New Orleans from the Cajuns of South Louisiana and even today the Cajuns regard New Orleans as “another country.”

Thus, while some non-Cajun plantation owners collected art in the Cajun parishes, Cajuns have never concerned themselves with art of any sort. Not even the “folk art” extant in other folk cultures is prized among Cajuns.

As for Cajun literature, there is none. Books are not prized possessions and the folklore has been passed along from one generation to another by word of mouth. Perhaps it is because of the high illiteracy rate that haunts the culture. Perhaps the culture never has been oriented to the printed word. Even today, the value placed on literature is extremely low.

An ironic result of this phenomenon was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s tale of “Evangeline,” the oft-repeated story of one of the thousands forced to leave Acadie (Nova Scotia) and resettle in southern Louisiana. Having been separated from her true love (Gabriel) during the relocation, Evangeline met him some years later in St. Martinville, La., only to find he had married another.

The Cajun folk tale was never written by a Cajun. Instead, Longfellow heard it from a student and wrote it, thereby becoming famous for a Cajun story. Even today, no Cajun writer has gained national prominence for disseminating the story of his ancestors or the status of the culture now.

Perhaps the Cajuns never felt a need to romanticize their culture since it was as real and as close as their immediate families. Perhaps the customs, traditions and French language were enough to hold the culture together without the quasi-mysticism that comes with romantic interpretation. Perhaps the Cajuns do not like to deal in the abstract. Whatever the reason, the sparse literary and artistic interpretations of the culture have come from outside the culture.

This was the world to which Rodrigue was born, the only child of a marriage between first cousins. Rodrigue’s hometown, New Iberia, is on the Bayou Teche, the fabled stream of Longfellow’s Evangeline. New Iberia was founded by the Spanish but the French-oriented Cajun culture has long since overwhelmed most Spanish influence.

Rodrigue says he grew up hearing stories about the Cajun culture from his aunts and uncles. Most of the stories were about Cajuns at the turn of the 20th Century. “This was a time when the Cajun culture was pure,” Rodrigue says. The people he heard his family speak about are the “ghosts” he paints today — naive Cajuns of a different era.

But it was a long journey from those days when he heard the stories of his culture to the time he first painted a picture of a Cajun. That journey took Rodrigue first to Lafayette where he majored in art at the University of Southwestern Louisiana. Then he traveled to California to take courses at the Los Angeles Art Center. He then moved to New York to work as a graphic designer.

“I guess it was in Los Angeles that it really hit me. Cajuns are different from the people in Los Angeles. They are different from anybody I have ever met. I guess I knew Cajuns were different before, but it never really hit me hard until I went to Los Angeles,” Rodrigue says.

During his short stay in New York, Rodrigue says he became disenchanted with big city living. “Everybody was out to make the buck. The buck was all important. That is not the Cajun way.”

And so, about eight years ago, Rodrigue returned to his native region to begin painting the ghosts of his heritage.

“I had seen a lot of paintings of Louisiana when I was young. But, I had noticed something odd. Nobody painted pictures of people. They were all landscapes. I thought that was wrong since it was the people who made my part of Louisiana different,” Rodrigue says.

But he knew first he had to develop a style of landscape painting before he could paint his people. He had to design the scenery for the stage on which his ghosts would act.

My first landscapes were very dark,” he says. “After all, in this part of Louisiana, the dark oaks and the dark Spanish moss make everything dark. There’s very little sky to be seen in this part of the country. The mood set by the scenery is one of darkness.”

After developing a decidedly different backdrop for his Cajuns, he was ready to make his first statement about the people.

He chose as his first theme “The Aioli Dinner.” This ancient tradition among the men of New Iberia is based in the Order of Creole Gourmets. Every month or so, the men of the order congregated at a house or plantation for a lavish eight-hour dinner. Many of the dishes were cooked in or topped with “aioli,” a garlic butter carefully prepared by one of the gourmets. After the aioli was prepared, it was the duty of the women to cook the meal. The young male children served the meal to the gourmets, scattered under the huge live oaks on the lawn.

The painting caused quite a stir among the people in New Iberia since the tradition had all but been forgotten. Rodrigue’s painting brought it back to life. Today, Rodrigue says, there are indications the Order of Creole Gourmets is going to make a comeback, perhaps due to his painting.

“The Aioli Dinner” today hangs in the Rodrigue gallery and is the only original of his that he owns. Perhaps one reason he refuses to sell it is that his grandfather is in the painting.

Even in this first painting, Rodrigue had given much thought to the Cajun culture before putting a brush to the canvas. The men and boys in the picture appear to be cut out of another painting and pasted on the landscape.

“That’s because the Cajuns, to my way of thinking, were ripped out of the Acadian landscape in Canada and literally forced to locate here against their will. Because of that, the Cajuns have never really ‘touched the earth’ here in Louisiana, nor will they ever. They are suspended here, somewhere between heaven and earth.”

In some of his paintings, the characters do not have feet, which compels the viewer to take note of the lack of ties with the land.

The people who came here from Acadie were not primitive. They came from a highly developed culture. But the land, the weather and a lot of other factors forced the Cajuns into a form of primitive living which they may have accepted but probably didn’t like,” Rodrigue says.

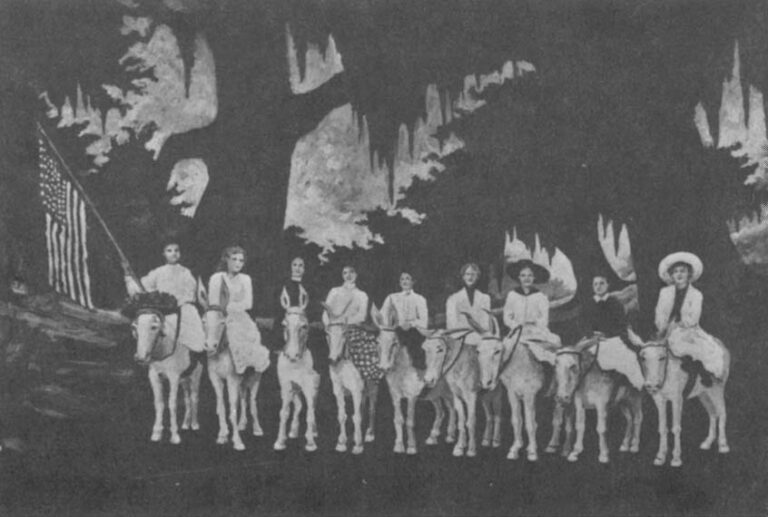

This attempt to be non-primitive in a primitive world is made humorous in Rodrigue’s “Mamou Riding Academy” which shows nine Cajun girls perched atop mules. “They all look very serious and what makes it so funny is that the girls are taking it all seriously,” Rodrigue says.

In “Mamou Riding Academy,” as in several of his pictures, the American flag is included. “It’s odd,” says Rodrigue, “that most Cajuns hold the flag and America so dear. And yet, America has barely recognized the Cajun.”

The theme of “nothing to do” is carried out in “Boudreaux in a Barrel.” Rodrigue explains that hide and seek was a popular game for a weekend afternoon in Cajun country. “There was literally nothing else to do,” he says.

“Breaux Bridge Band” is another attempt to show the Cajun doing what he liked to do — play music. “The Breaux Bridge Band was very famous,” Rodrigue says. “They went all over the country. Some of the musicians in the band studied in Paris.”

And yet, the band is pictured in front of a barn over which towers a gigantic, primitive live oak.

The fact that Rodrigue is giving romantic interpretations to the folk culture is likely to have a significant impact on the culture’s future. But, more importantly, perhaps, is the fact that Rodrigue is making a reputation for himself (through his Cajun paintings) outside his native region.

For example, the artist was given a 1974 honorable mention award from the French government for his painting “The Class” which was entered in competition at the Grand Palais on the Champs Elysees in Paris. “Le Salon” exhibition, begun in 1881, is the oldest in France.

Rodrigue is listed in the “International Directory of Art,” and in 1974, the International Academy of Literature, Arts and Sciences awarded Rodrigue a gold medal for recognition of merits achieved in the field of art.

The artist has shown his works all over the south and recently completed a one-man show in Boston, Mass.

“I think that was an important exhibition for me,” Rodrigue says. “It is a region where Cajuns are virtually unknown.”

Most important for Rodrigue and the Cajun culture, perhaps, is a major art book featuring Rodrigue paintings. Oxmoor House, a division of Southern Living, has scheduled the book for an October 1976, release. It will include most of Rodrigue’s paintings plus short, colorful stories describing the folk tales that inspired the works of art.

The book could have a broad impact on the culture. “I think the book will make the Cajuns even prouder of who they are. They’ll know that people all over America will be reading about them and their homes.

Thus, it seems that once again, the artist has been the mirror for a folk culture, as he has been hundreds of times in the long history of art. As the first major Cajun artist in the culture’s history, Rodrigue apparently holds a key to the culture’s future. He and others like him will most certainly affect the relationship between the remnants of the culture and the rest of America.

Like Frederick Remington and his relationship with the cowboy culture, Rodrigue holds in his brush and paints the key to how mainstream America reacts to the romance of the Cajun culture.

Received in New York on January 12, 1976.

©1976 Dave Peyton

Dave Peyton is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Huntington Advertiser (West Virginia). This article may be published with credit to Mr. Peyton, The Huntington Advertiser, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.